Healthcare in Germany

Germany has a universal[1] multi-payer health care system paid for by a combination of statutory health insurance (Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung) and private health insurance (Private Krankenversicherung).[2][3][4][5][6]

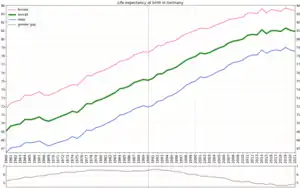

The turnover of the national health sector was about US$368.78 billion (€287.3 billion) in 2010, equivalent to 11.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and about US$4,505 (€3,510) per capita.[7] According to the World Health Organization, Germany's health care system was 77% government-funded and 23% privately funded as of 2004.[8] In 2004 Germany ranked thirtieth in the world in life expectancy (78 years for men). It was tied for eighth place in the number of practicing physicians, at 3.3 per 1,000 persons. It also had very low infant mortality rate (4.7 per 1,000 live births).[note 1][9] In 2001 total spending on health amounted to 10.8 percent of gross domestic product.[10]

According to the Euro health consumer index, which placed it in seventh position in its 2015 survey, Germany has long had the most restriction-free and consumer-oriented healthcare system in Europe. Patients are allowed to seek almost any type of care they wish whenever they want it.[11] In 2017, the government health system in Germany kept a record reserve of more than €18 billion which made it one of the healthiest healthcare systems in the world at the time.[12]

History

1883

Germany has the world's oldest national social health insurance system,[1] with origins dating back to Otto von Bismarck's social legislation, which included the Health Insurance Bill of 1883, Accident Insurance Bill of 1884, and Old Age and Disability Insurance Bill of 1889. Bismarck stressed the importance of three key principles; solidarity, the government is responsible for ensuring access by those who need it, subsidiarity, policies are implemented with the smallest political and administrative influence, and corporatism, the government representative bodies in health care professions set out procedures they deem feasible.[13] Mandatory health insurance originally applied only to low-income workers and certain government employees, but has gradually expanded to cover the great majority of the population.[14]

1883–1970

Unemployment insurance was introduced in 1927. In 1932, the Berlin treaty (1926) expired and Germany's modern healthcare system started shortly after the expiration of Berlin Treaty. In 1956, Laws on Statutory health insurance (SHI) for pensioners come into effect. New laws came in effect in 1972 to help finance and manage hospitals. In 1974 SHI covered students, artists, farmers and disabled living shelters. Between 1977 and 1983 several cost laws were enacted. Long-term care insurance (Pflegeversicherung) was introduced in 1995.

1976–present

Since 1976, the government has convened an annual commission, composed of representatives of business, labor, physicians, hospitals, and insurance and pharmaceutical industries.The commission takes into account government policies and makes recommendations to regional associations with respect to overall expenditure targets.[15] Historically, the level of provider reimbursement for specific services is determined through negotiations between regional physicians' associations and sickness funds.

In 1986, expenditure caps were implemented and were tied to the age of the local population as well as the overall wage increases.

As of 2007, providers have been reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis; the amount to be reimbursed for each service is determined retrospectively to ensure that spending targets are not exceeded. Capitated care, such as that provided by U.S. health maintenance organizations, has been considered as a cost-containment mechanism, but since it would require consent of regional medical associations, it has not materialized.[16]

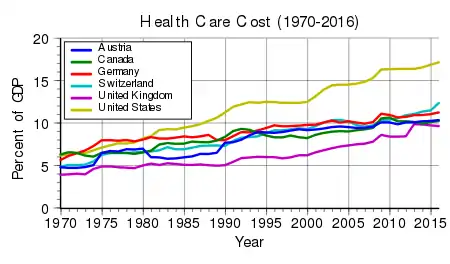

Copayments were introduced in the 1980s in an attempt to prevent overutilization and control costs. The average length of hospital stay in Germany has decreased in recent years from 14 days to 9 days, still considerably longer than average stays in the U.S. (5 to 6 days).[17][18] The difference is partly driven by the fact that hospital reimbursement is chiefly a function of the number of hospital days as opposed to procedures or the patient's diagnosis. Drug costs have increased substantially, rising nearly 60% from 1991 through 2005. Despite attempts to contain costs, overall health care expenditures rose to 10.7% of GDP in 2005, comparable to other western European nations, but substantially less than that spent in the U.S. (nearly 16% of GDP).[19]

The system is decentralized with private practice physicians providing ambulatory care, and independent, mostly non-profit hospitals providing the majority of inpatient care. Approximately 92% of the population are covered by a 'Statutory Health Insurance' plan, which provides a standardized level of coverage through any one of approximately 1,100 public or private sickness funds. Standard insurance is funded by a combination of employee contributions, employer contributions and government subsidies on a scale determined by income level. Higher-income workers sometimes choose to pay a tax and opt-out of the standard plan, in favor of 'private' insurance. The latter's premiums are not linked to income level but instead to health status.[20][21]

Regulation

Since 2004, the German healthcare system has been regulated by the Federal Joint Committee (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss), a public health organization authorized to make binding regulations growing out of health reform bills passed by lawmakers, along with routine decisions regarding healthcare in Germany.[22] The Federal Joint Committee consists of 13 members, who are entitled to vote on these binding regulations. The members composed of legal representatives of the public health insurances, the hospitals, the doctors and dentists and three impartial members. Also, there are five representatives of the patients with an advisory role who are not allowed to vote.[23][24]

The German law about the public health insurance (Fünftes Sozialgesetzbuch) sets the framework agreement for the committee.[25] One of the most important tasks is to decide which treatments and performances the insurances have to pay for by law.[26] The principle about these decisions is that every treatment and performance has to be required, economic, sufficient and appropriate.[27]

Health insurance

Since 2009, health insurance has been compulsory for the whole population in Germany, when coverage was expanded from the majority of the population to everyone.[28]

As of 2021, salaried workers and employees who earn in total less than €64,350 per year or €5,362.50 per month[29] are automatically enrolled into one of currently around 105[30] public non-profit "sickness funds" (Krankenkassen). The fund has a common rate for all members, and is paid for with joint employer-employee contributions. The employer pays half of the contribution, and the employee pays the other half.[21] Insured persons can also choose optional plans that include higher deductibles and are therefore cheaper.[31] Plans that include high reimbursements if no medical services are used are also possible.[32] In addition, insured persons can forego certain services with some health insurance companies and choose cheaper plans.[33] Self-employed workers and those who are unemployed without benefits must pay the entire contribution themselves. Provider payment is negotiated in complex corporatist social bargaining among specified self-governed bodies (e.g. physicians' associations) at the level of federal states (Länder).[34] The sickness funds are mandated to provide a unique and broad benefit package and cannot refuse membership or otherwise discriminate on an actuarial basis.[34] Social welfare beneficiaries are also enrolled in statutory health insurance, and municipalities pay contributions on their behalf.[34]

Besides the statutory health insurance (Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung), which covers the vast majority of residents, some residents can instead choose private health insurance: those with a yearly income above €64,350 (2022, unchanged from 2021),[29] students and civil servants. About 11% of the population has private health insurance.[21][35][36][37] Most civil servants benefit from a tax-funded government employee benefit scheme that covers a percentage of the costs, and cover the rest of the costs with a private insurance contract. Recently, private insurers provide various types of supplementary coverage as an add upon of the SHI benefit package (e.g. for glasses, coverage abroad and additional dental care or more sophisticated dentures). Health insurance in Germany is split in several parts. The largest part of 89% of the population is covered by statutory public health insurance funds, regulated under by the Sozialgesetzbuch V (SGB V), which defines the general criteria of coverage, which are translated into benefit packages by the Federal Joint Committee. The remaining 11% opt for private health insurance, including government employees.

Public health insurance contributions are based on the worker's salary. Private insurers charge risk-related contributions.[21] This may result in substantial savings for younger individuals in good health. With age, private contributions tend to rise and a number of individuals formerly cancelled their private insurance plan in order to return to statutory health insurance; this option is now only possible for beneficiaries under 55 years.[20][21][38]

Reimbursement for outpatient care was previously on a fee-for-service basis but has changed into basic capitation according to the number of patients seen during one quarter, with a capped overall spending for outpatient treatments and region. Moreover, regional panel physician associations regulate number of physicians allowed to accept Statutory Health Insurance in a given area. Co-payments, which exist for medicines and other items are relatively low compared to other countries.[39]

Insurance systems

Germany has a universal system with two main types of health insurance. Germans are offered three mandatory health benefits, which are co-financed by employer and employee: health insurance, accident insurance, and long-term care insurance.

Accident insurance for working accidents (Arbeitsunfallversicherung) is covered by the employer and basically covers all risks for commuting to work and at the workplace.

Long-term care insurance (Pflegeversicherung) is covered half and half by employer and employee and covers cases in which a person is not able to manage their daily routine (provision of food, cleaning of apartment, personal hygiene, etc.). It is about 2% of a yearly salaried income or pension, with employers matching the contribution of the employee.

There are two separate types of health insurance: public health insurance (gesetzliche Krankenversicherung) and private insurance (private Krankenversicherung).[21] Both systems struggle with the increasing cost of medical treatment and the changing demography. About 87.5% of the persons with health insurance are members of the public system, while 12.5% are covered by private insurance (as of 2006).[40]

In 2013 a state funded private care insurance was introduced (private Pflegeversicherung).[41] Insurance contracts that fit certain criteria are subsidized by €60 per year. It is expected that the number of contracts will grow from 400,000 by end of 2013 to over a million within the next few years.[42] These contracts have been criticized by consumer rights foundations.[43]

Insuring organizations

The German federal legislature has reduced the number of public health insurance organizations from 1209 in 1991 down to 123 in 2015.[44]

The public health insurance organizations (Krankenkassen) are the Ersatzkassen (EK), Allgemeine Ortskrankenkassen (AOK), Betriebskrankenkassen (BKK), Innungskrankenkassen (IKK), Knappschaft (KBS), and the Landwirtschaftliche Krankenkasse (LKK).[45]

As long as a person has the right to choose health insurance, they can join any insurance that is willing to include them.

| Numbers | Number of members including retired persons |

Open on federal level |

Open on state level |

Not open | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All public insurance organisations | 109 | 72.8 M | 43 | 46 | 29 |

| Betriebskrankenkassen | 84 | 10.9 M | 33 | 32 | 28 |

| Allgemeine Ortskrankenkassen | 11 | 26.5 M | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Landwirtschaftliche Krankenkassen | 1 | 0.6 M | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ersatzkassen | 6 | 28.0 M | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Innungskrankenkassen | 6 | 5.2 M | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Knappschaft | 1 | 1.6 M | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Public insurance

Regular salaried employees must have public health insurance unless their income exceeds €64,350 per year (2021).[47][21] This is referred to as the compulsory insurance limit (Versicherungspflichtgrenze). If their income exceeds that amount, they can choose to have private health insurance instead. Freelancers and self-employed persons can have public or private insurance, regardless of their income.[21] Public health insurers are not forced to accept self-employed persons, which can create difficulties for foreign freelancers, who can get refused by both public and private health insurers.[48] Since health insurance coverage is a requirement for their residence permit, they can be forced to leave the country.

In the public system, the premium

- is set by the Federal Ministry of Health based on a fixed set of covered services as described in the German Social Law (Sozialgesetzbuch – SGB), which limits those services to "economically viable, sufficient, necessary and meaningful services";

- is not dependent on an individual's health condition, but a percentage (currently 14.6%, half of which is covered by the employer) of salaried income under €64,350 per year (in 2021). Additionally, each public health insurance provider charges an additional contribution rate, which is 1.3% on average (2021),[49][21] but goes up to 2.7%;[50][51]

- includes family members of any family members, or "registered member" (Familienversicherung – i.e., husband/wife and children are free);[21]

- is a "pay as you go" system – there is no saving for an individual's higher health costs with rising age or existing conditions. Instead, the solidarity principle applies in which the current active generation pays forward for the costs of the current retired generation.[52]

Private insurance

In the private system, the premium

- is based on an individual agreement between the insurance company and the insured person defining the set of covered services and the percentage of coverage;

- depends on the amount of services chosen and the person's risk and age of entry into the private system;[21]

- is used to build up savings for the rising health costs at higher age (as required by law).[53] This is otherwise known as aging provisions (Alterungsrückstellungen).[54][52]

For persons who have opted out of the public health insurance system to get private health insurance, it can prove difficult to subsequently go back to the public system, since this is only possible under certain circumstances, for example if they are not yet 55 years of age and their income drops below the level required for private selection. Since private health insurance is usually more expensive than public health insurance, although not always,[55] the higher premiums must then be paid out of a lower income. During the last twenty years private health insurance became more and more expensive and less efficient compared with the public insurance.[56]

In Germany, all privately financed products and services for health are assigned as part of the 'second health market'.[57] Unlike the 'first health market' they are usually not paid by a public or private health insurance. Patients with public health insurance paid privately about €1.5 billion in this market segment in 2011, while already 82% of physicians offered their patients in their practices individual services being not covered by the patient's insurances; the benefits of these services are controversial discussed.[58] Private investments in fitness, for wellness, assisted living, and health tourism are not included in this amount. The 'second health market' in Germany is compared to the United States still relatively small, but is growing continuously.

Self-payment (international patients without any national insurance coverage)

Besides the primary governmental health insurance and the secondary private health insurance mentioned above, all governmental and private clinics generally work in an inpatient setting with a prepayment system, requiring a cost estimate that needs to be covered before the perspective therapy can be planned. Several university hospitals in Germany have therefore country-specific quotes for pre-payments that can differ from 100% to the estimated costs and the likelihood of unexpected additional costs, i.e. due to risks for medical complications.[59][60]

Economics

A simple outline of the health sector in three areas provides an "onion model of health care economics" by Elke Dahlbeck and Josef Hilbert[61] from the Institut Arbeit und Technik (IAT) at the University of Applied Sciences Gelsenkirchen:[62] Core areas are the ambulatory and inpatient acute care and geriatric care, and health administration. Around it is located wholesale and supplier sector with pharmaceutical industry, medical technology, healthcare, and wholesale trade of medical products. Health-related margins are the fitness and spa facilities, assisted living, and health tourism.

According to one author in 2009, an almost totally regulated health care market like in the UK would not be very productive, but also a largely deregulated market as in the United States would not be optimal for Germany. Both systems would suffer concerning sustainable and comprehensive patient care. Only a hybrid of social well-balanced and competitive market conditions would be optimal.[63] Nevertheless, forces of the healthcare market in Germany are often regulated by a variety of amendments and health care reforms at the legislative level, especially by the Social Security Code (Sozialgesetzbuch- SGB) in the past 30 years.

Health care, including its industry and all services, is one of the largest sectors of the German economy. Direct inpatient and outpatient care equivalent to just about a quarter of the entire 'market' – depending on the perspective.[7] As of 2007 a total of 4.4 million people were working in the health care sector, about one in ten employees.[64] In 2010, the total expenditure in health economics was about €287.3 billion in Germany, equivalent to 11.6 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) and about €3,510 per capita.[65]

Drugs costs

The pharmaceutical industry plays a major role in Germany within and beyond direct health care. Expenditure on pharmaceutical drugs is almost half of those for the entire hospital sector. Pharmaceutical drug expenditure grew by an annual average of 4.1% between 2004 and 2010. Such developments caused numerous health care reforms since the 1980s. An example of 2010 and 2011: First time since 2004 the drug expenditure fell from €30.2 billion in 2010 to €29.1 billion in 2011, i.e. a fall of €1.1 billion or 3.6%. It was caused by restructuring the Social Security Code: manufacturer discount 16% instead of 6%, price moratorium, increasing discount contracts, increasing discount by wholesale trade and pharmacies.[66]

As of 2010, Germany has used reference pricing and incorporated cost sharing to charge patients more when a drug is newer and more effective than generic drugs.[67] However, as of 2013 total out-of-costs for medications were capped at 2% of income, and 1% of income for people with chronic diseases.[68]

Statistics

.jpg.webp)

In a sample of 13 developed countries Germany was seventh in its population weighted usage of medication in 14 classes in 2009 and tenth in 2013. The drugs studied were selected on the basis that the conditions treated had high incidence, prevalence and/or mortality, caused significant long-term morbidity and incurred high levels of expenditure and significant developments in prevention or treatment had been made in the last 10 years. The study noted considerable difficulties in cross border comparison of medication use.[69] As of 2015 it had the highest number of dentists in Europe with 64,287.[70]

Major diagnoses

In 2002, the top diagnosis for male patients released from the hospital was heart disease, followed by alcohol-related disorders and hernias. For women, a 2020 study lists the three most common diagnoses as heart disease, dementia and cardiovascular diseases.[71]

In 2016, an epidemiological study highlighted significant differences among the 16 federal states of Germany in terms of prevalence and mortality for the major cardiovascular diseases (CVD). The prevalence of major CVD was negatively correlated with the number of cardiologists, whereas it did not show any correlation with the number of primary care providers, general practitioners or non-specialized internists. A more relevant positive relation was found between the prevalence or mortality of major CVD and the number of residents per chest pain unit. Bremen, Saarland and the former East German states had higher prevalence and mortality rates for major CVD and lower mean lifespan durations.[72]

Hospitals

Types:

There are three main types of hospital in the German healthcare system:

- Public hospitals (öffentliche Krankenhäuser).

- Charitable hospitals (frei gemeinnützige Krankenhäuser).

- Private hospitals (Privatkrankenhäuser).

The average length of hospital stay in Germany decreased in recent years from 14 days to 9 days,[73] still considerably longer than average stays in the United States (5 to 6 days)[74] from 1991 through 2005, drug costs have increased substantially, rising nearly 60% . Despite attempts to contain costs, overall health care expenditures rose to 10.7% of GDP in 2005, comparable to other western European nations, but substantially less than that spent in the U.S. (nearly 16% of GDP).[75]

In 2017 the BBC reported that compared with the United Kingdom the Caesarean rate, the use of MRI for diagnosis and the length of hospital stay are all higher in Germany.[76]

Waiting times and capacity

In 1992, a study by Fleming et al. 19.4% of German respondents said they had waited more than 12 weeks for their surgery. (cited in Siciliani & Hurst, 2003, p. 8),[77]

In the Commonwealth Fund 2010 Health Policy Survey in 11 countries, Germany reported some of the lowest waiting times. Germans had the highest percentage of patients reporting their last specialist appointment took less than 4 weeks (83%, vs. 80% for the U.S.), and the second-lowest reporting it took 2 months or more (7%, vs. 5% for Switzerland and 9% for the U.S.). 70% of Germans reported that they waited less than 1 month for elective surgery, the highest percentage, and the lowest percentage (0%) reporting it took 4 months or more.[78] Waits can also vary somewhat by region. Waits were longer in eastern Germany according to the KBV (KBV, 2010), as cited in "Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators".[79]

As of 2015, waiting times in Germany were reported to be low for appointments and surgery, although a minority of elective surgery patients face longer waits.[80][81]

According to the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians in 2016,(KBV, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung), the body representing contract physicians and contract psychotherapists at federal level, 56% of Social Health Insurance patients waited 1 week or less, while only 13% waited longer than 3 weeks for a doctor's appointment. 67% of privately insured patients waited 1 week or less, while 7% waited longer than 3 weeks. The KBV reported that both Social Health Insurance and privately insured patient experienced low waits, but privately insured patients' waits were even lower. [82]

As of 2022, Germany had a large hospital sector capacity measured in beds with the highest rate of intensive care beds among high income countries and the highest rate of overall hospital capacity in Europe.[83] High capacity on top of significant day surgery outside of hospitals (especially for ophthalmology and orthopaedic surgery) with doctors paid fee-for-service for activity performed are likely factors preventing long waits, despite hospital budget limitations.[77] Activity-based payment for hospitals also is linked to low waiting times (Siciliani & Hurst, 2003, 33–34, 70).[77] As of 2014, Germany had introduced Diagnosis-related group activity-based payment for hospitals with a soft cap budget limit.[84]

See also

Notes

- Metrics for infant mortality vary between countries and therefore might not be directly comparable. The United States, for example, marks babies under 500g as being able to be saved and thus counts them as deaths where as Germany does not include them in their infant mortality rate. Also the infant mortality rate may be due to social factors rather than its healthcare system.

References

- Bump, Jesse B. (October 19, 2010). "The long road to universal health coverage. A century of lessons for development strategy" (PDF). Seattle: PATH. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

Carrin and James have identified 1988—105 years after Bismarck's first sickness fund laws—as the date Germany achieved universal health coverage through this series of extensions to growing benefit packages and expansions of the enrolled population. Bärnighausen and Sauerborn have quantified this long-term progressive increase in the proportion of the German population covered mainly by public and to a smaller extent by private insurance. Their graph is reproduced below as Figure 1: German Population Enrolled in Health Insurance (%) 1885–1995.

Carrin, Guy; James, Chris (January 2005). "Social health insurance: Key factors affecting the transition towards universal coverage" (PDF). International Social Security Review. 58 (1): 45–64. doi:10.1111/j.1468-246X.2005.00209.x. S2CID 154659524. Retrieved March 10, 2013.Initially the health insurance law of 1883 covered blue-collar workers in selected industries, craftspeople and other selected professionals.6 It is estimated that this law brought health insurance coverage up from 5 to 10 per cent of the total population.

Bärnighausen, Till; Sauerborn, Rainer (May 2002). "One hundred and eighteen years of the German health insurance system: are there any lessons for middle- and low income countries?" (PDF). Social Science & Medicine. 54 (10): 1559–1587. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00137-X. PMID 12061488. Retrieved March 10, 2013.As Germany has the world's oldest SHI [social health insurance] system, it naturally lends itself to historical analyses

- "Duden – Krankenkasse – Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition, Synonyme". duden.de.

- The use of the term "Krankenkasse" for both public and private health insurances is so widespread that Duden doesn't even label this usage as colloquial.

- "The Case for Universal Health Care in the United States". Cthealth.server101.com. Archived from the original on 2018-04-23. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- "German Health Care System – an Overview – Germany Health Insurance System". germanyhis.com.

- DiPiero, Albert (2004). "Universal Problems & Universal Healthcare: 6 COUNTRIES — 6 SYSTEMS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2006.

- A. J. W. Goldschmidt: Der 'Markt' Gesundheitswesen. In: M. Beck, A. J. W. Goldschmidt, A. Greulich, M. Kalbitzer, R. Schmidt, G. Thiele (Hrsg.): Management Handbuch DRGs, Hüthig / Economica, Heidelberg, 1. Auflage 2003 (ISBN 3-87081-300-8): S. C3720/1-24, with 3 revisions / additional deliveries until 2012

- World Health Organization Statistical Information System: Core Health Indicators

- Liu, K; Moon, M; Sulvetta, M; Chawla, J (1992). "International infant mortality rankings: a look behind the numbers". Health Care Financing Review. 13 (4): 105–18. PMC 4193257. PMID 10122000.

- Germany country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (December 2005). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Outcomes in EHCI 2015" (PDF). Health Consumer Powerhouse. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-06. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "Überschüsse bei den Krankenkassen – wohin mit dem Geld?". Medscape (in German). Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- Clarke, Emily. "Health Care Systems: Germany" (PDF). Civitas. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "History of German Health Care System". Photius.com. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- Kirkman-Liff BL (1990). "Physician Payment and Cost-Containment Strategies in West Germany: Suggestions for Medicare Reform". Journal of Health Care Politics, Policy and Law. 15 (1): 69–99. doi:10.1215/03616878-15-1-69. PMID 2108202.

- Henke KD (May 2007). "[External and internal financing in health care]". Med. Klin. (Munich) (in German). 102 (5): 366–72. doi:10.1007/s00063-007-1045-0. PMID 17497087. S2CID 46136822.

- "Germany: Health reform triggers sharp drop in number of hospitals". Allianz. 25 July 2005. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- "Average Length of Hospital Stay, by Diagnostic Category --- United States, 2003". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- Borger C, Smith S, Truffer C, et al. (2006). "Health spending projections through 2015: changes on the horizon". Health Aff (Millwood). 25 (2): w61–73. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.25.w61. PMID 16495287.

- "Gesetzliche Krankenversicherungen in Vergleich". Archived from the original on 2014-06-01. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- Bouliane, Nicolas. "How to choose German health insurance". allaboutberlin.com. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- Reinhardt, Uwe E. (24 July 2009). "A German Import That Could Help U.S. Health Reform". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

Germany's joint committee was established in 2004 and authorized to make binding regulations growing out of health reform bills passed by lawmakers, along with routine coverage decisions. The ministry of health reserves the right to review the regulations for final approval or modification. The joint committee has a permanent staff and an independent chairman.

- "Germany : International Health Care System Profiles". international.commonwealthfund.org. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- Health care in Germany: The German health care system. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. 2018-02-08.

- Olberg, Britta; Fuchs, Sabine; Matthias, Katja; Nolting, Alexandra; Perleth, Matthias; Busse, Reinhard (2017-10-17). "Evidence-based decision-making for diagnostic and therapeutic methods: the changing landscape of assessment approaches in Germany". Health Research Policy and Systems. 15 (1): 89. doi:10.1186/s12961-017-0253-1. ISSN 1478-4505. PMC 5645898. PMID 29041939.

- Obermann, Konrad. "Understanding the German Health Care System" (PDF). Mannheim Institute of Public Health. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- "An education handbook about the federal joint committee and its tasks, published by the federal medical association in germany" (PDF). website of the German federal medical association. 2009.

- Busse, Reinhard; Blümel, Miriam; Knieps, Franz; Bärnighausen, Till (August 2017). "Statutory health insurance in Germany: a health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition". The Lancet. 390 (10097): 882–897. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31280-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 28684025.

- "Germany Health Insurance". Thegermanyeye.com. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- "Krankenkassen-Fusionen: Fusionskalender - Krankenkassen.de". www.krankenkassen.de. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "TK-Tarif 300Plus".

- "Wahltarif Beitragsrückerstattung".

- "TK-Tarif Select".

- Germany Healthcare Sector Organization, Management and Payment Systems Handbook Volume 1 Strategic Information and Basic Laws. Lulu.com. 29 April 2015. ISBN 978-1-4330-8585-7.

- "Krankenversicherung in Deutschland". gesundheitsinformation.de (in German). Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- David Squires; Robin Osborn; Sarah Thomson; Miraya Jun (14 November 2013). International Profiles of Health Care Systems, 2013 (PDF) (Report).

- "Statutory health insurance". www.gkv-spitzenverband.de (in German). Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- Schmitt, Thomas (21 May 2012). "Wie Privatpatienten in die Krankenkasse schlüpfen" (in German). Handelsblatt.

- "Zuzahlung und Erstattung von Arzneimitteln". Bundesgesundheitsministerium (in German). Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- SOEP – Sozio-oekonomische Panel 2006: Art der Krankenversicherung

- "Nicht verfügbar". pflegeversicherung-test.de.

- "Nicht verfügbar". pflegeversicherung-test.de.

- "Vorsicht Pflege-Bahr: Stiftung Warentest rät von staatlich geförderten Pflege-Tarifen ab". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 16 April 2013.

- National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds: List of German Public Health Insurance Companies Archived 7 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Mannheim Institute of Public Health (MIPH), Heidelberg University: Understanding the German Health Care System

- "Liste aller Krankenkassen". gesetzlicheKrankenkassen.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- "Pflichtversicherungsgrenze Versicherungspflichtgrenze GKV PKV". www.versicherungspflichtgrenzen.de. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- "Which health insurance do you need for your German visa?". allaboutberlin.com. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- "Zusatzbeitrag". BKK-VBU - Meine Krankenkasse (in German). Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- "What is a health insurance Zusatzbeitrag?". allaboutberlin.com. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- "Zusatzbeitrag der Krankenkassen - Krankenkassen.de". www.krankenkassen.de. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- "Health insurance in Germany: an introduction to pick the right provider". Settle in Berlin. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- "§ 146 VAG - Einzelnorm". www.gesetze-im-internet.de. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- "Alterungsrückstellungen | A | Lexikon | AOK-Bundesverband". aok-bv.de. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- "Private Health Insurance in Germany - Pros and Cons". Thegermanyeye.com. 2019-01-18. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- Greß, Stefan (2007). "Private health insurance in Germany: consequences of a dual system". Healthcare Policy. 3 (2): 29–37. ISSN 1715-6572. PMC 2645182. PMID 19305777.

- J. Kartte, K. Neumann. Der zweite Gesundheitsmarkt. Die Kunden verstehen, Geschäftschancen nutzen, o.O.. Roland Berger Strategy Consultants, Munich, 2007

- Pfeiffer D, "Spitzenverband der Gesetzlichen Krankenkassen GKV". dapd, 4 February 2012

- "Plan your treatment". helios-gesundheit.de/ (in German). Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Treatment Inquiry & Appointment". Heidelberg University Hospital. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Josef Hilbert". Iat.eu. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- E. Dahlbeck, J. Hilbert. "Beschäftigungstrends in der Gesundheitswirtschaft im regionalen Vergleich". Gelsenkirchen: Inst. Arbeit und Technik. Forschung Aktuell, Nr. 06/2008

- A. J. W. Goldschmidt, J. Hilbert. "Von der Last zur Chance – Der Paradigmenwechsel vom Gesundheitswesen zur Gesundheitswirtschaft". In: A. J. W. Goldschmidt, J. Hilbert (eds.), Gesundheitswirtschaft und Management. kma-Reader – Die Bibliothek für Manager. Volume 1: Gesundheitswirtschaft in Deutschland. Die Zukunftsbranche. Wikom-Verlag (Thieme), Wegscheid, 2009 (ISBN 978-3-9812646-0-9), pp. 20–40

- Statistisches Bundesamt. "Beschäftigung in der Gesundheitswirtschaft steigt weiter an". Press release no. 490, Berlin, 17 December 2008

- Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland, Wiesbaden, 2012

- B. Häusler, A. Höer, E. Hempel: Arzneimittel-Atlas 2012. Springer, Berlin u. a. 2012 (ISBN 978-3-642-32586-1) Archived 2013-01-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "How Germany is reining in health care costs: An interview with Franz Knieps". McKinsey. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Hossein, Zare; Gerard, Anderson (1 September 2013). "Trends in cost sharing among selected high income countries—2000–2010". Health Policy. Health System Performance Comparison: New Directions in Research and Policy. 112 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.05.020. ISSN 0168-8510. PMID 23809913.

- "International Comparison of Medicines Usage: Quantitative Analysis" (PDF). Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Ballas, Dimitris; Dorling, Danny; Hennig, Benjamin (2017). The Human Atlas of Europe. Bristol: Policy Press. p. 79. ISBN 9781447313540.

- "Gesundheitliche Lage der Frauen in Deutschland, Publisher: Robert Koch-Institut, 2020" (PDF).

- Christina Dornquast; Stefan N. Willich; Thomas Reinhold (30 October 2018). "Prevalence, Mortality, and Indicators of Health Care Supply—Association Analysis of Cardiovascular Diseases in Germany". Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 5: 158. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2018.00158. OCLC 7900068347. PMC 6218414. PMID 30425992. S2CID 53100112.

- Length of hospital stay, Germany Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine group-economics.allianz.com, undated

- Length of hospital stay, U.S. MMWR, CDC

- Borger C, Smith S, Truffer C, et al. (2006). "Health spending projections through 2015: changes on the horizon". Health Affairs. 25 (2): w61–73. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.25.w61. PMID 16495287.

- "NHS Health Check: How Germany's healthcare system works". BBC News. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Siciliani, S., & Hurst, J. (2003). "Explaining Waiting Times Variations for Elective Surgery across OECD Countries". OECD Health Working Papers, 7, 8, 33–34, 70. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/40674618616

- The Commonwealth Fund (2010). Commonwealth Fund 2010 Health Policy Survey in 11 Countries (pp. 19–20). New York.

- "Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators". Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2011.

- "Studie: So lange warten die Deutschen beim Arzt". Fernarzt (in German). Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- Ärzteblatt, Deutscher Ärzteverlag GmbH, Redaktion Deutsches (2015-08-03). "Facharzttermine im internationalen Vergleich: Geringe Wartezeiten in Deutschland". Deutsches Ärzteblatt (in German). Retrieved 2022-05-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (2016). https://gesundheitsdaten.kbv.de/cms/html/24045.php ["Health data: Die Wartezeit ist für die meisten kurz"] [The wait is short for most].

- Brunn, Matthias; Kratz, Torsten; Padget, Michael; Clément, Marie-Caroline; Smyrl, Marc (2022-03-24). "Why are there so many hospital beds in Germany?". Health Services Management Research. 36 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1177/09514848221080691. ISSN 0951-4848. PMID 35331042. S2CID 247678071.

- Busse R., & Blümel, M. (2014). "Germany: health system review". Health Systems in Transition, 16(2), 142–148.

_4.jpg.webp)