Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry III (28 October 1016 – 5 October 1056), called the Black or the Pious, was Holy Roman Emperor from 1046 until his death in 1056. A member of the Salian dynasty, he was the eldest son of Conrad II and Gisela of Swabia.[1][2][3]

| Henry III | |

|---|---|

_Miniatur.jpg.webp) Henry with the symbols of rulership attending the consecration of the Stavelot monastery church on 5 June 1040, mid-11th-century miniature | |

| Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Reign | 25 December 1046 – 5 October 1056 |

| Coronation | 25 December 1046 St. Peter's Basilica, Rome |

| Predecessor | Conrad II |

| Successor | Henry IV |

| King of Germany (formally King of the Romans) | |

| Reign | 14 April 1028 – 5 October 1056 |

| Coronation | 14 April 1028 Aachen Cathedral |

| Predecessor | Conrad II |

| Successor | Henry IV |

| King of Italy and Burgundy | |

| Reign | 4 June 1039 – 5 October 1056 |

| Predecessor | Conrad II |

| Successor | Henry IV |

| Born | 28 October 1016 |

| Died | 5 October 1056 (aged 39) Bodfeld |

| Burial | Imperial Palace of Goslar (heart); Speyer Cathedral (body) |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Salian Dynasty |

| Father | Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Gisela of Swabia |

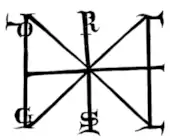

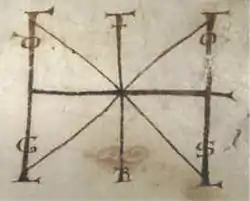

| Signum manus (1049) |  |

Henry was raised by his father, who made him Duke of Bavaria in 1026, appointed him co-ruler in 1028 and bestowed him with the duchy of Swabia and the Kingdom of Burgundy ten years later in 1038.[4] The emperor's death the following year ended a remarkably smooth and harmonious transition process towards Henry's sovereign rule, that was rather uncharacteristic for the Ottonian and Salian monarchs.[4] Henry succeeded Conrad II as Duke of Carinthia and King of Italy and continued to pursue his father's political course on the basis of virtus et probitas (courage and honesty), which led to an unprecedented sacral exaltation of the kingship. In 1046 Henry ended the papal schism, was crowned Emperor by Pope Clement II, freed the Vatican from dependence on the Roman nobility and laid the foundation for its empire-wide authority. In the duchies, Henry enforced the sovereign royal right of disposition, thereby ensuring tighter control. In Lorraine, this led to years of conflict from which he emerged victorious. Another sphere of defiance formed in southern Germany from 1052 to 1055. Henry III died, aged only 39. Modern historians, however, identify the final years of his reign as the beginning of a crisis in the Salian monarchy.[5][6]

Early life

Born on 28 October 1016,[7] or 1017,[8] Henry was the son of Conrad of Worms and Gisela of Swabia.[9][10] Conrad was a Franconian aristocrat[11] who held domains along the river Rhine when his son was born.[12] He was related to the imperial Ottonian dynasty through his great-grandmother, Liutgard—a daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I.[13] Conrad may have fathered a son before his marriage to Gisela, because a royal charter referred to his sons in 1024, but its reliability is dubious.[14] Henry was always mentioned as his father's sole son in charters issued after February 1028.[14] Gisela, who was descended from Charlemagne, had a strong claim both to Swabia and to Burgundy.[15] Conrad was Gisela's third husband and she had given birth to three sons and possibly a daughter during her previous two marriages.[15] Conrad was illiterate, but Gisela was solicitous to their son's education and Henry learnt to read.[16][17]

The last Ottonian monarch, Henry II, died on 13 July 1024.[18] The German aristocrats who assembled at Kamba to elect his successor proclaimed Conrad of Worms king on 4 September.[19] Conrad's opponent formed a coalition that included his stepson, Ernest II, Duke of Swabia.[20] They took up arms against the King in the second half of 1025, but he forced most of them into submission before the end of the year.[21] Ernest asked his mother Gisela to mediate a reconciliation and she convinced the eight-year-old Henry also to intervene on Ernest's behalf in early 1026.[22] Ernest had to promise to provide military assistance to Conrad to achieve a pardon.[22]

Conrad designated Henry as his heir in Augsburg in February 1027.[14] A year later, before departing for his first Italian campaign, Conrad charged Bruno, Bishop of Augsburg, with Henry's guardianship.[14] Historian Stefan Weinfurter states that Bruno, who was Emperor Henry II's brother, was "particularly well-suited to impart regal concepts and imperial traditions" to his ward.[23] Bruno accompanied Henry to Rome where they attended Conrad's imperial coronation on Easter 1027.[24]

Dynastic consolidation and co-ruler

Emperor Conrad II was determined to strengthen royal authority in Germany.[25] Ignoring the claim of Emeric, the son of King Stephen I of Hungary, to Bavaria, Conrad persuaded the Bavarian aristocrats to acknowledge Henry as their duke in Regensburg on 24 July 1027.[26][27] Henry's appointment to the duchy was unprecedented—Bavaria had never been ruled by a ten-year-old duke.[24] In autumn 1027, the Emperor sent Bishop Werner of Strasbourg to Constantinople to win a bride from the Byzantine imperial family for Henry, but Werner's sudden death put an end to the negotiations with Emperor Constantine VIII.[28]

At Conrad's initiative, the "clergy and the people" elected Henry his co-ruler and Pilgrim, Archbishop of Cologne, crowned Henry king in Aachen on Easter 1028.[24][29] Henry was thereafter named the "hope of the empire" on his father's seals in accordance with Byzantine customs.[30] Conrad sent another embassy to Constantinople.[31] Constantine VIII's successor, Emperor Romanos III Argyros, proposed the hand of one of his sisters to Henry, but Conrad's envoy, Count Manegold of Donauwörth, refused the offer since she was already married.[32]

Bishop Bruno of Augsburg died on 6 April 1029 and Conrad appointed Egilbert, Bishop of Freising, as Henry's new tutor.[33] Bavaria made raids into Hungary and provoked a Hungarian counter-attack.[34] Conrad assembled Bavarian, Lorrainian and Bohemian troops and invaded Hungary in June 1030. Insufficient supplies forced him to return and the Hungarians attacked and beat his army at Vienna.[34] Conrad left Bavaria, assigning the task to deal with the Hungarians to the twelve-year-old Henry.[34] Egilbert of Freising started negotiations with Stephen I of Hungary on Henry's behalf.[35] Egilbert agreed to cede lands along the frontier to the Hungarians in return for the release of their prisoners.[36] Henry accepted the terms and signed the peace treaty during a meeting with Stephen I in Hungary in early 1031.[37]

Egilbert's mentorship lasted until Henry's accolade in late June or early July in 1033.[38] Egilbert received generous grants for his services on 19 July.[38]

Upon Rudolph III of Burgundy's death Conrad II claimed the title to the Burgundian succession and marched his army to Burgundy during the winter of 1032/1033. In two large-scale military summer campaigns in 1033 and 1034, Conrad defeated his rival Odo II, Count of Blois. On 1 August 1034, Conrad II officially incorporated the Kingdom of Burgundy into the Holy Roman Empire at a ceremony held in the Cathedral of Geneva.[39]

Henry and Gunhilda of Denmark, the daughter of Emma of Normandy and Canute the Great, King of Denmark, England and Norway, were engaged on 18 May 1035.[38] On the same occasion Conrad declared war on the Liutizi, a pagan Slavic tribe[40] and deposed his brother-in-law, Adalbero, Duke of Carinthia.[41] Conrad entrusted Canute with Southern Jutland upon their children's marriage, which took place in Nijmegen during the 1036 feast of Pentecost.[42]

In 1038, Henry was called to aid his father in Italy. On their return trip along the Adriatic coast Gunhilda died from an epidemic that apparently had also caused the death of Herman IV of Swabia near Naples.[3] In 1039, Emperor Conrad II also died, and Henry succeeded him as king and imperator in spe.[43]

Royal and imperial reign

Inaugural tour

Henry inaugurated his reign with a tour through his domains. In the Low Countries he received homage of Gothelo I, Duke of Upper and Lower Lorraine, and in Cologne, he was joined by Herman II, Archbishop of Cologne, who accompanied him and his mother to Saxony, where he established the town of Goslar as a future imperial residence. Heading an army he entered Thuringia where he met Eckard II, Margrave of Meissen, whose advice and counsel he sought with regard to the recent successes of Duke Bretislav I of Bohemia in Poland.[44]

In Bohemia only a delegation that offered hostages appeased Henry and he disbanded his army and continued his tour. He visited Bavaria, when, upon his departure, King Peter Orseolo of Hungary sent raiding parties into Swabia. At Ulm, Henry convened a diet and received acknowledgement from the present Italian princes.

Henry returned to Ingelheim where he was recognized by a Burgundian embassy and by Aribert, Archbishop of Milan, whom he had supported against his father.[42] Henry's consensus with Aribert was an attempt to solve the old interior imperial conflict with Conrad. When Adalbero I of Eppenstein was deposed by Conrad, Henry also inherited the Duchy of Carinthia, by which he became triple-duke (Bavaria, Swabia and Carinthia) on top of being triple-king of Germany, Burgundy and Italy.[45]

Conflict with Bohemia and Hungary

Henry led his first military campaign as sovereign in 1040 into Bohemia, where Bretislav I intended to establish a separate archbishopric. After having attended the reform sessions of a number of monasteries, Henry summoned his army at Stablo. In July he joined with contingents at Goslar and deployed his entire army at Regensburg. He set out on 13 August and was soon ambushed in the passes of the Bohemian Forest and forced to retreat with heavy losses at the Battle at Brůdek. Only after the release of a large number of Bohemian hostages, including Bretislav's son, did Henry procure the release of his prisoners. Upon conclusion of the peace, Henry retreated hastily. On his return to Germany, he appointed Suidger—the future Pope Clement II—as bishop of Bamberg.[44]

In 1040, Peter of Hungary was overthrown by Samuel Aba and fled to Germany, where Henry welcomed him despite their former enmity. Bretislav was now deprived of his former ally, upon which Henry prepared another campaign into Bohemia. On 15 August, almost exactly one year after his last expedition he set out once more, was victorious and signed a peace treaty with Bretislav at Regensburg.[44]

Henry spent Christmas 1041 at Strasbourg, and received emissaries from the Duchy of Burgundy, where he travelled during the new year to settle administrative and judicial matters. On the road near Basel he learnt of Hungarian raids into Bavaria and bestowed the duchy to a certain Henry VII, a relative of the last independent duke. At Cologne, Henry summoned the royal princes, who unanimously declared war on Hungary. After he had sent a wedding delegation to Agnes of Poitou he set out in September 1042 and successfully subdued the western territories of Hungary. Aba fled to his eastern estates, as Henry installed a cousin as steward, who was, however, quickly removed after the emperor had left.

After Christmas at his chosen imperial residence, Goslar, he received foreign guests. Duke Bretislav appeared in person, a Kievan marriage embassy was dismissed and the ambassadors of Casimir I of Poland were rejected as the duke did not show up in person. Henry left for the French border near Ivois, in order to meet King Henry I of France, most likely to discuss the impending marriage to the princess of Aquitaine. Henry next returned to Hungary and forced Aba to recognize the Danubian territories, a former donation of Stephen I of Hungary, pro causa amicitiae (for friendship's sake). These territories had been ceded to Hungary after Conrad II's defeat of 1030. This border remained in place between Hungary and Austria until 1920.

Promotion of Speyer

Gisela, Henry's mother, died in March 1043. She was solemnly buried in Speyer. The king appeared barefoot, in tears, and penitent robe at the funeral, his arms crossed, threw himself on the ground in front of the crowd and moved everyone to tears. With Henry's emulation of Christian humble self-denial, he intended to prove his ability to hold pious kingship. Historians have referred since to the period of the "Christomimetic royalty". Henry promoted Speyer far more than his father Conrad. Shortly before leaving for Italy, he endowed the church with a magnificently illustrated gospel book, called the Codex Aureus Escorialensis, also known as the Speyer Gospel. The Dome of Speyer was gradually extended during the following years and a large burial sector was created for future rulers and royal continuity.[46][47]

In October 1043, Henry, displaying deep personal piety, announced from the pulpit of the Konstanz Minster that the Peace and Truce of God be respected all over his realms on that very day. This day was to be remembered as the "Day of Indulgence" or "Day of Pardon". He, Henry, granted universal indulgence and pardon while in turn promised himself to forgive all injuries suffered, pains endured and to refrain from all acts of vengeance[42] and he encouraged all his imperial subjects to do likewise.[45][48]

Marriage to Agnes of Poitou

In 1043 Henry married Agnes of Poitou, the daughter of Duke William V of Aquitaine and Agnes of Burgundy. She resided at the court of her stepfather, Geoffrey Martel, Count of Anjou. The association with this boisterous vassal of the king of France and her consanguinity with Henry (both were descendants of Henry the Fowler) stirred up some consternation among many clerics, who opposed their union. The marriage, however, took place anyway and Agnes was crowned queen at Mainz.[49]

Conflicts in Lorraine and pacification in Hungary

Henry spent the winter at Utrecht, where he again announced an indulgence. In April 1044, Gothelo, Duke of Lower and Upper Lorraine died. Henry opposed the political particularism of the dukes. In order to diminish their power he appointed the younger son Gothelo II as duke of the Lower duchy instead of Godfrey, Gothelo I's eldest son who had already been installed as duke of Upper Lorraine. Henry claimed that Gothelo I's deathbed wish was to bequeath both sons with a share of the estate. Godfrey, who had been a faithful servant of Henry, eventually rose in rebellion. Henry attempted to reconcile the brothers at Nijmegen but failed. However, Henry considered the ducal fief to be a royal office and insisted on his prerogative when he appointed dignitaries at his discretion.[48]

On 6 July 1044 Henry, accompanied by Peter Orseolo, entered Hungary at the head of a moderately sized force, which engaged Samuel Aba's sizeable army. Discord among the Magyar forces prevented cohesive manoeuvres and their troops quickly dispersed upon Henry's onslaught. At Székesfehérvár Peter regained his fief as King of Hungary.[50] Aba was eventually captured by Peter and beheaded. Henry implemented regular Imperial administration in Hungary.[44]

Upon his return from the Hungarian expedition, Godfrey of Upper Lorraine established new alliances, including with Henry of France, who might support him in a likely future insurrection.[51] The emperor reacted promptly and summoned Godfrey to Aachen. He was convicted and lost the duchy of Upper Lorraine and his fief of the county of Verdun.[51] Godfrey fled and took up arms in revolt. Henry wintered at Speyer and prepared for the Lorraine campaign of 1045.

In early 1045, Henry entered Lorraine at the head of an army, and besieged and conquered Godfrey's castle of Böckelheim (near Kreuznach). After he had taken a number of castles, lack of supplies forced him to leave. He garrisoned the ducal castles and cities to prevent any incursions by Godfrey and left for Burgundy. Godfrey had stirred up rebellions in Burgundy by creating conflicts between the imperialist faction and the domestic royal faction, which supported an independent Burgundy. Louis, Count of Montbéliard, challenged and defeated Reginald I, Count of Burgundy. When Henry arrived, Reginald and Gerold, Count of Geneva, paid homage and Burgundy was subsequently incorporated into the empire.[52]

Height of power

Henry settled political issues with the Lombard magnates at Augsburg. In Goslar he invested Otto with the duchy of Swabia, the count palatine, Henry I with the Duchy of Lorraine and Baldwin with the Margraviate of Antwerp. During the preparations of the jaunt to Hungary where Henry had intended to spend Pentecost with King Peter, a wooden floor collapsed in a residence where Bruno, Bishop of Würzburg was killed. In Hungary, Peter presented Henry with the Golden Lance and pledged an oath of fealty among his nobles. The crown of Hungary was bestowed on Peter in perpetuity and the kingdoms of Germany and Hungary were at peace. In July, Godfrey surrendered and was imprisoned at Giebichenstein.

War in Lorraine

Henry fell ill at Tribur in October, so Henry of Bavaria and Otto of Swabia chose Otto's nephew and successor as count palatine, Henry I of Lorraine as Henry III's successor. However, Henry III recovered, but remained without an heir. In early 1046, Henry's old advisor, Eckard of Meissen, died, leaving Meissen to Henry. He bestowed it on William, count of Orlamünde.[53]

Henry then moved to Lower Lorraine, where Gothelo II had just died and Dirk IV of Holland had seized Flushing. Henry personally led a campaign against Count Dirk and recovered Flushing. He gave it to Bernold, Bishop of Utrecht, and returned to Aachen to celebrate Pentecost and to decide on the fate of Lorraine. Henry restored Godfrey, but transferred the county of Verdun to the bishop of the city, which angered the duke. Henry bestowed the lower duchy to Frederick, Duke of Lower Lorraine and appointed Adalbert, archbishop of Bremen.

The right of a German court to try an Italian bishop was considered very controversial. The problem culminated in the Investiture Controversy that overshadowed the reigns of Henry's son and grandson. Henry moved on to Saxony and held imperial courts at Quedlinburg, Merseburg (in June) and Meissen, where he appointed his daughter Beatrice abbess and ended the strife between Siemomysł, Duke of Pomerania and Casimir of Poland.[45]

Imperial coronation

.jpg.webp)

Henry summoned the senior princes of the empire and departed to Italy. His ally, Aribert of Milan, had recently died and the Milanese citizens had chosen Guido to succeed him. In Rome, the three popes Benedict IX, Sylvester III and Gregory VI contested the pontifical honours.

Benedict was a Tusculan who had previously renounced the throne, Sylvester a Crescentian, and Gregory was a reformer (simoniac). Henry marched to Verona and Pavia, where he held court and dispensed justice. He moved on to Sutri and held a second court on 20 December 1046 where he deposed all three papal candidates. In Rome he held a synod, declared all Roman priests unfit for office and as Adalbert of Bremen refused the honour, Henry appointed Suidger of Bamberg, who was acclaimed by the people and clergy. He adopted the name Clement II.[54][55]

On Christmas Day 1046, Clement was consecrated, and Henry and Agnes crowned emperor and empress. The Roman citizenry awarded Henry the Golden Chain of the Patriciate and elevated him to patricius. Henry visited Frascati, the capital of the counts of Tusculum and seized all castles of the Crescentii family. Joined by the pope, he ventured to southern Italy and reverted most of his father's policies.[53]

At Capua, Henry was received by Prince Guaimar IV of Salerno and Capua. However, Henry returned Capua to the twice-deprived Prince Pandulf IV, a highly unpopular choice. Guaimar had been acclaimed as Duke of Apulia and Calabria by the Norman mercenaries under William Iron Arm and his brother Drogo of Hauteville.

In return, Guaimar had recognized the conquests of the Normans and invested William as his vassal with the comital title. Henry made Drogo, William's successor in Apulia, a direct vassal of the imperial crown. He did likewise to Ranulf Drengot, the count of Aversa, who had been a vassal of Guaimar as Prince of Capua. Thus, Guaimar was deprived of his greatest vassals, his principality split in two, and his greatest enemy reinstated. These decisions made Henry unpopular among the Lombards, and Benevento, although a papal vassal, would not approve of him. The Italian circuit was completed when he arrived at Verona in May 1047.[45]

Henry's appointments

Upon his return to Germany, Henry assigned the offices that had been left vacant. He transferred his last personal duchy, Carinthia, to Welf, made his Italian chancellor Hunfried Bishop of Ravenna, appointed to several other sees, installing Guido in Piacenza, his chaplain Theodoric in Verdun, the provost Herman of Speyer in Strasbourg and his German chancellor Theodoric in Constance. The important Lorrainian bishoprics of Metz and Trier received, respectively, Adalbero and Eberhard, a chaplain.[44]

Henry was at Metz in July 1047 when Godfrey once again rose in rebellion. Godfrey was now allied with Baldwin of Flanders, his son (the margrave of Antwerp), Dirk of Holland, and Herman, Count of Hainaut. Henry gathered an army and went north, where he gave Adalbert of Bremen Godfrey's former lands and oversaw the trial by combat of Thietmar, the brother of Bernard II, Duke of Saxony, accused of plotting to kill the king. Bernard, an enemy of Adalbert, was now clearly on Henry's bad side. Henry made peace with the new king of Hungary, Andrew I, and moved into the Netherlands. At Flushing, he was defeated by Dirk. The Hollanders sacked Charlemagne's palace at Nijmegen and burnt Verdun. Godfrey then performed a public penance and assisted in the reconstruction of Verdun.[44]

The rebels besieged Liège, which was stoutly defended by Bishop Wazo. Henry gave Upper Lorraine to one Adalbert and left. The pope had died in the meantime and Henry chose Poppo of Brixen to succeed him, who adopted the name Damasus II. Henry gave Bavaria to one Cuno and, at Ulm in January 1048, Swabia to Otto of Schweinfurt, called the White. Henry met Henry of France again, probably at Ivois in October and at Christmas, envoys from Rome came to seek a new pope, Damasus having died. Henry's most enduring papal selection was Bruno of Toul, who took office as Leo IX, under whom the Church would be divided between East and West. Henry's final appointment of this long spate was a successor to Adalbert in Lorraine. For this, he appointed Gerard of Chatenoy, a relative of Adalbert and Henry himself.[56][57]

Peace in Lorraine

1049 proved to be a successful year. Dirk of Holland was defeated and killed. Adalbert of Bremen managed a peace with Bernard of Saxony and negotiated a treaty with the missionary monarch Sweyn II of Denmark. With the assistance of Sweyn and Edward the Confessor of England, whose enemies Baldwin had harboured, Baldwin of Flanders was harassed by sea and unable to escape the onslaught of the imperial army. At Cologne, the pope excommunicated Godfrey and Baldwin. The former abandoned his allies and was imprisoned by the emperor again. Baldwin also gave in under Henry's pressure. Finally, the war had ended in the Low Countries and Lorraine.[58]

Final years

In 1051, Henry undertook a third Hungarian campaign but suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Vértes. His troops fled the battlefield over a range of hills still called "Vértes" ("Armoured") because discarded armour has been found there for centuries. In Lower Lorraine, Lambert, Count of Louvain; and Richildis, widow of Herman of Mons and new bride of Baldwin of Antwerp, caused trouble. Godfrey was released and given Lower Lorraine, to safeguard the unstable peace attained two years before.

In 1052, Henry undertook a fourth campaign against Hungary, and besieged Pressburg without success, as the Hungarians sank his supply ships on the Danube river. Henry was unable to continue his campaign and in fact never tried again. Henry did send a Swabian army to assist Leo in Italy, but he recalled it quickly. At Christmas 1052, Cuno of Bavaria was summoned to Merseburg and deposed by a small council of princes for his conflict with Gebhard III, Bishop of Regensburg. Cuno revolted.[44]

Final wars in Germany

On 26 June 1053, at Tribur, the young Henry, born 11 November 1050, was elected king of Germany. Andrew of Hungary almost made peace, but Cuno convinced him otherwise. Henry appointed his young son duke of Bavaria and went to deal with the ongoing insurrection. Henry sent another army to assist Leo in the Mezzogiorno against the Normans. He himself had confirmed their conquests as his vassals. Leo, without assistance from Guaimar (distanced from Henry since 1047), was defeated at the Battle of Civitate on 18 June 1053 by Humphrey, Count of Apulia; Robert Guiscard, his younger brother; and Prince Richard I of Capua. The Swabians were cut to pieces.[52]

In 1054, Henry traveled north to deal with the bellicose Casimir of Poland. He transferred Silesia from Bretislav to Casimir. Bretislaus nevertheless remained loyal to the end. Henry turned westwards and crowned his young son at Aachen on 17 July and then marched into Flanders, as the two Baldwins had rebelled again. John of Arras, who had seized Cambrai before, had been forced out by Baldwin of Flanders and so turned to the Emperor. In return for inducing Liutpert, Bishop of Cambrai, to give John the castle, John would lead Henry through Flanders. The Flemish campaign was a success, but Liutpert could not be convinced.

Bretislav, who had regained Silesia in a short war, died in 1054. The margrave of Austria, Adalbert, however, successfully resisted the depredations of Cuno and the raids of the king of Hungary. Henry could thus direct his attention elsewhere than rebellions for once. He returned to Goslar, the city where his son had been born and which he had raised to imperial and ecclesiastic grandeur with his palace and church reforms. He passed Christmas there and appointed Gebhard of Eichstedt as the next holder of the Petrine see, with the name Victor II. He was the last of Henry's four German popes.[53]

Preparing Italy and Germany for his death

In 1055, Henry turned south, to Italy again, for Boniface III of Tuscany, ever an imperial ally, had died, and his widow, Beatrice of Bar, had married Godfrey of Lorraine (1054). First, however, he gave his old hostage, Spitignev, the son of Bretislaus, to the Bohemians as duke. Spitignev did homage and Bohemia remained securely, loyally, and happily within the Imperial fold. By Easter, Henry had arrived in Mantua. He held several courts, one at Roncaglia—where, a century later (1158), Frederick Barbarossa held a far more important diet—and sent out his missi dominici to establish order. Godfrey, ostensibly the reason for the visit, was not well received by the people and returned to Flanders. Henry met the pope at Florence and arrested Beatrice, for marrying a traitor, and her daughter Matilda, later to be such an enemy of Henry's son. The young Frederick of Tuscany, son of Beatrice, refused to come to Florence and died within days.[52]

Henry returned and at Christmas 1055 he arranged the subsequent marriage of his successor. In Zürich, the heir to the throne, Henry IV, was engaged to Bertha of Turin of the House of Savoy.[59]

Henry entered a Germany in turmoil. A staunch ally against Cuno in Bavaria, Gebhard of Regensburg, was implicated in a plot against the king along with Cuno and Welf of Carinthia. Sources diverge here: some claim only that the retainers of the princes plotted the undoing of the king. Whatever the case, it all came to naught, and Cuno died of plague, with Welf soon following him to the grave. Baldwin of Flanders and Godfrey were at it again, besieging Antwerp, and they were defeated again. Henry's reign was clearly changing in character: old foes were dead or dying and old friends as well.[53]

Herman of Cologne died. Henry appointed his confessor, Anno, as Herman's successor. Henry of France, so long eyeing Lorraine greedily, met for a third time with the emperor at Ivois in May 1056. The French king, not renowned for his tactical or strategic prowess, but admirable for his personal valour on the field, had a heated debate with the German king and challenged him to single combat. Henry fled at night from this meeting. Once in Germany again, Godfrey made his final peace, and Henry went to the northeast to deal with a Slav uprising after the death of William of Meissen. He fell ill on the way and took to bed. He freed Beatrice and Matilda and had those with him swear allegiance to the young Henry, whom he commended the pope, present.

On 5 October, not yet forty, Henry died at Bodfeld, the imperial hunting lodge in the Harz mountains.[60] His heart was transferred to Goslar and his body to Speyer, to rest next to his father's in the family vault of the cathedral of Speyer. Henry had been one of the most powerful of the Holy Roman Emperors. His authority as king in Burgundy, Germany and Italy was only rarely questioned, his power over the church was at the root of what the reformers he sponsored later fought against in his son, and his achievement in binding to the empire her tributaries was clear. Nevertheless, his reign is often pronounced a failure in that he apparently left problems far beyond the capacities of his successors to handle. The Investiture Controversy was largely the result of his church politics, though his popemaking gave the Roman diocese to the reform party.[61] He united all the great duchies save Saxony to himself at one point or another but gave them all away. His most enduring and concrete monument may be the impressive palace (kaiserpfalz) at Goslar.[47]

Family and children

Henry III was married twice and had at least eight children:

- With his first wife, Gunhilda of Denmark:[62]

- Beatrice (1037 – 13 July 1061), abbess of Quedlinburg and Gandersheim[63]

- Adelaide II (1045, Goslar – 11 January 1096), abbess of Gandersheim from 1061 and Quedlinburg from 1063[64]

- Gisela (1047, Ravenna – 6 May 1053)[64]

- Matilda (October 1048 – 12 May 1060, Pöhlde), married 1059 Rudolf of Rheinfelden, duke of Swabia and anti-king (1077)[64]

- Henry, his successor[60]

- Conrad (1052, Regensburg – 10 April 1055), duke of Bavaria (from 1054)[64]

- Judith (1054, Goslar – 14 March 1092 or 1096), married, firstly, in 1063, Solomon of Hungary, and, secondly, in 1089, Ladislaus I Herman, Duke of Poland[64]

- With an anonymous concubine:

- Azela, mother of bishop Johannes of Speyer[65]

See also

References

- Jan Habermann. "The curious story of Henry III". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Heinrich III. mit neuem Geburtsjahr". Regesta Imperii - Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Ryley 1964, p. 274.

- Rudolf Schieffer (30 September 2013). Christianisierung und Reichsbildungen: Europa 700–1200. C.H.Beck. pp. 150–. ISBN 978-3406653766.

- Friedrich Prinz. "Kaiser Heinrich III. seine widersprüchliche Beurteilung und deren Gründe, in Historische Zeitschrift No. 246 (1988)" (PDF). MGH Bibliothek. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Thomas Zotz. "Spes imperii – Heinrichs III. Herrschaftspraxis und Reichsintegration" (PDF). Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Gerhard Lubich; Dirk Jäckel (2016). "Das Geburtsjahr Heinrichs III.: 1016". Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters: 581–592.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor". Britannica.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 37.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 87.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 5.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 27.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 6.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 28.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 34.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 22.

- Johann Heinrich Albers (1872). Die Erziehung Heinrich III. in ihrer Bedeutung für die Entwicklung der staatlichen und kirchlichen Verhältnisse des 11. Jahrhunderts: Inaugural-Dissertation. Universitäts-Buchdruckerei.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 42.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 19.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 78.

- Wolfram 2006, pp. 78–79.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 79.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 85.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 141.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 54.

- Wolfram 2006, pp. 141, 187.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 53.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 28.

- Schutz 2010, p. 141.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 29.

- Weinfurter 1999, pp. 29–30.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 30.

- Wolfram 2006, pp. 141, 231.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 231.

- Wolfram 2006, pp. 232–233.

- Wolfram 2006, pp. 233–234.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 233.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 142.

- Previté-Orton, Charles William. "The early history of the house of Savoy (1000-1233)". Cambridge, The University press Archive. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 222.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 84.

- Kampers, Franz. "Henry III." The Catholic Encyclopedia Archived 6 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 4 January 2016

- Wolfram 2006, p. 345.

- Friedrich Steinhoff (1865). Das Königthum und Kaiserthum Heinrich III.: Eine verfaszungsgeschichtl. Monografie. Deuerlich. pp. 17–.

- "Heinrich III". Deutsche Biographie. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Reuter, Timothy (2006). Medieval Polities and Modern Mentalities. Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-1139459549.

- John H. Arnold (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Christianity. OUP Oxford. pp. 486–. ISBN 978-0191015007.

- Boshof, Egon (2008). Die Salier. Kohlhammer Verlag. p. 112. ISBN 978-3170201835.

- Constance Brittain Bouchard (1987). Sword, Miter, and Cloister: Nobility and the Church in Burgundy, 980–1198. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801419743.

- Ryley 1964, p. 285.

- Schutz 2010, p. 126.

- Bernd Schneidmüller; Stefan Weinfurter (2003). Die deutschen Herrscher des Mittelalters: historische Portraits von Heinrich I. bis Maximilian I. (919–1519). C.H. Beck. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-3406509582.

- Stefan Weinfurter (2015). "Ordnungskonfigurationen im Konflikt Das Beispiel Kaiser Heinrichs III". Vorträge und Forschungen. Uni Heidelberg. 54: 79–100. doi:10.11588/vuf.2001.0.17742. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Mary Stroll (2011). Popes and Antipopes: The Politics of Eleventh Century Church Reform. Brill. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-9004217010.

- Thorndike, Lynn; Shotwell, James Thomson (1928). The History of Medieval Europe p.285. Dalcassian Publishing Company. pp. 285–. GGKEY:TY4HYGTG9WL.

- C. Stephen Jaeger (2013). The Envy of Angels: Cathedral Schools and Social Ideals in Medieval Europe, 950–1200. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 202–. ISBN 978-0812200300.

- John S. Ott; Anna Trumbore Jones (2007). The Bishop Reformed: Studies of Episcopal Power and Culture in the Central Middle Ages. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0754657651.

- Stefan Weinfurter (January 2006). "Das Jahrhundert der Salier (1024–1125)". Francia. Academia. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Elisabeth van Houts (31 January 2019). Married Life in the Middle Ages, 900-1300. OUP inrichOxford. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-0-19-251974-0.

- Whitney 1968, p. 31.

- von Giesebrecht, Wilhelm (1841). Annales Altahenses: eine Quellenschrift zur Geschichte des eilften Jahrhunderts aus Fragmenten und Excerpten hergestellt. Duncker und Humblot. pp. 125–.

- Keynes 1999, p. 297.

- Bernhardt 2002, p. 311.

- Weinfurter 1999, p. 46.

- Lohse 2013, pp. 217–227.

Sources

- Bernhardt, John W. (2002). Itinerant Kingship and Royal Monasteries in Early Medieval Germany, c. 936-1075. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39489-9.

- Keynes, Simon (1999). "The cult of King Alfred". In Lapidge, Michael; Godden, Malcolm; Keynes, Simon (eds.). Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge University Press.

- Lohse, Tillmann (2013). "Heinrich IV., seine Halbschwester Azela und die Wahl zum Mitkönig am 26. Juni 1053 in Tribur: Zwei übersehene Quellenbelege aus Goslar". Niedersächsisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte (in German). 85: 217–227.

- North, William (2006). "Henry III". In Emmerson, Richard K.; Clayton-Emmerson, Sandra (eds.). Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Routledge.

- Norwich, John Julius. The Normans in the South 1016–1130. Longmans: London, 1967.

- Ryley, Caroline M. (1964). "The Emperor Henry III". In Gwatkin, H. M.; Whitney, J. P. (eds.). The Cambridge Medieval History:Germany and the Western Empire. Vol. III. Cambridge University Press.

- Schutz, Herbert (2010). The Medieval Empire in Central Europe: Dynastic Continuity in the Post-Carolingian Frankish Realm, 900–1300. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1443819664.

- Weinfurter, Stefan (1999). The Salian Century: Main Currents in an Age of Transition. The Middle Ages. Translated by Bowlus, Barbara M. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812235088.

- Whitney, J. P. (1968). "The Reform of the Church". In Tanner, J. R.; Previté-Orton, C. W.; Brooke, Z. N. (eds.). The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. V. Cambridge University Press.

- Wolfram, Herwig (2006). Conrad II, 990–1039: Emperor of Three Kingdoms. Translated by Kaiser, Denise A. The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 027102738X.