History of Christianity

The history of Christianity concerns the Christian religion, Christian countries, and the Christians with their various denominations, from the 1st century to the present. Christianity originated with the ministry of Jesus, a Jewish teacher and healer who proclaimed the imminent Kingdom of God and was crucified c. AD 30–33 in Jerusalem in the Roman province of Judea.[1] His followers believe that, according to the Gospels, he was the Son of God and that he died for the forgiveness of sins and was raised from the dead and exalted by God, and will return soon at the inception of God's kingdom.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| History of religions |

|---|

The earliest followers of Jesus were apocalyptic Jewish Christians.[1] Christianity remained a Jewish sect for centuries, diverging gradually from Judaism over doctrinal, social and historical differences.[2] Christianity spread as a grassroots movement that became established by the third century.[3][4][5][6] The Roman Emperor Constantine I became the first Christian emperor and in 313, issued the Edict of Milan expressing tolerance for all religions thereby legalizing Christian worship.[7] Various Christological debates about the human and divine nature of Jesus occupied the Christian Church for three centuries, and seven ecumenical councils were called to resolve them.[8]

Christianity played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization in Europe after the Fall of Rome.[9][10][11][12][13] In the Early Middle Ages, missionary activities spread Christianity towards the west and the north.[14] During the High Middle Ages, Eastern and Western Christianity grew apart, leading to the East–West Schism of 1054. Growing criticism of the Roman Catholic church and its corruption in the Late Middle Ages (from the 14th to 15th centuries) led to the Protestant Reformation and its related reform movements, which concluded with the European wars of religion.[15][16][17]

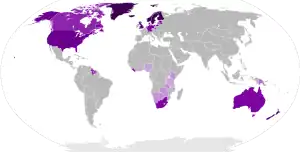

In the twenty-first century, Christianity has expanded throughout the world.[18] Today, there are more than two billion Christians worldwide and Christianity has become the world's largest religion,[18] and most widespread religion.[19] Within the last century, the center of growth has shifted from West to East and from North to the global South.[20][21][22][23]

Origins to 312

Jesus

Frances M. Young writes in the Cambridge History of Christianity that "The death of Jesus by crucifixion, together with his resurrection from the dead, lies at the heart of Christianity."[24] Tensions surround the figure of Jesus as the historical instigator and foundation of Christianity around whom "apparently legendary features" have clustered.[24] These tensions can be seen in the twenty-first century distinction between the ‘Jesus of history’ and the ‘Christ of faith’.[24]

The primary, though not the only, sources of information regarding Jesus' life and teachings are the four canonical gospels, and to a lesser extent the Acts of the Apostles and the Pauline epistles. Virtually all scholars of antiquity accept that Jesus was a historical figure.[25][note 1]

Yet, since the nineteenth century, there have been repeated attempts to discern, by various methods, what might be history and what might be legend in the gospels.[29] Young lists some of the difficulties:

- Post-Enlightenment questions about the perspectives and beliefs of those who told the story, not least the belief in miracles and supernatural power

- The nature of the sources and the question of their mutual compatibility

- Considerable time-spans between the events and the accounts

- Questions about the validity of oral traditions

- Gaps in the evidence

- Issues about the authenticity of material remains

- Post-Reformation rejection of relics and their veneration.[30]

Yet it is precisely Christology, the dogmas concerning the divinity and humanity of Christ, which have made Christianity what it is. The clarification of these doctrines, against all the variant forms of Christianity around in the earliest period, was impelled by the ‘cult’ of Jesus, and by the fact that his story was quickly incorporated into an over-arching cosmic narrative.[31]

An approximate chronology of Jesus can be estimated from non-Christian sources, and confirmed by correlating them with New Testament accounts.[32][33] Jesus was most likely born between 7 and 2 BC and died 30–36 AD.[32][34] The baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist can be dated approximately from Josephus' references (Antiquities 18.5.2) to a date before AD 28–35.[35][36][37][38]

Amy-Jill Levine says "there is a consensus of sorts on the basic outline of Jesus' life. Most scholars agree that Jesus was baptized by John, debated with fellow Jews on how best to live according to God’s will, engaged in healings and exorcisms, taught in parables, gathered male and female followers in Galilee, went to Jerusalem, and was crucified by Roman soldiers during the governorship of Pontius Pilate (26–36 CE)".[39]

According to the Gospels, Jesus is the Son of God, who was crucified c. AD 30–33 in Jerusalem.[1] His followers believed that he was raised from the dead and exalted by God, heralding the coming Kingdom of God.[1] Jesus had urged his followers to worship God, act without violence or prejudice, and care for the sick, hungry, and poor. He had also criticized the hypocrisy of the religious establishment which drew the ire of the authorities.[40] The Talmud says Jesus was executed for sorcery and for leading the people into apostasy.[41]

Political, social and religious setting

The religious, social, and political climate of 1st-century Roman Judea and its neighbouring provinces was extremely diverse, and often characterized by socio-political turmoil,[1][42][43] with numerous Judaic movements that were both religious and political.[44] The Jewish Messiah concept, promising a future "anointed" leader (messiah or king) from the Davidic line, had developed in apocalyptic literature over the previous centuries.[45][1]

Jewish diaspora

When Christianity spread beyond Judaea, it first arrived in Jewish diaspora communities.[46] The dispersion of the Jewish people from their homeland had begun in BC 587/6 when Nebuchadnezzar conquered Israel and took slaves from Jerusalem into Babylon.[47] When later allowed to return, not everyone did so. Those remaining outside the homeland became a somewhat separate community unto themselves later referred to by scholars as the diaspora.[48] [note 2]

Many scholars have emphasized differences between Palestinian Jews and diaspora Jews, but it is likely they still had a common Judaism. Being Jewish had both ethnic and religious elements, and the basic aspects of Jewish faith - circumcision, the Sabbath, and other central practices prescribed by the Torah - were most likely carried out by the individual within the context of home and family no matter where they lived.[49]

One real difference of diaspora Judaism was in their use of Greek as both a spoken and written language, not only in everyday usage, but also for religious purposes. This demonstrates a high level of acculturation called Hellenization whose extent, depth and significance has long been, and continues to be, contested.[50]

Tessa Rajak writes in the Cambridge History of Christianity that "The crushing of the revolt in [AD 70–73], celebrated by Rome’s issue of the famous ‘Judaea capta’ coins, ...resulted in a degradation of the standing of Jews everywhere”.[51] In AD 115/16, diaspora Jews revolted, and it was only in the second half of the second century that Judaism entered a less turbulent era.[52]

According to Rajak, the essence of diaspora lies in powerlessness more than in power, and "the early Christian communities shared many of the same experiences."[53]

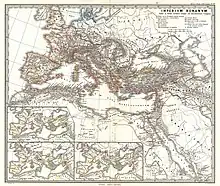

Roman Empire

The Christian gospel came into a Roman Empire which had only recently emerged from a long series of civil wars, and which would experience two more major periods of civil war over the next centuries.[54] This period saw the growth of the cult of the emperor which regarded the emperor as the "elect" of god.[55] Romans of this era feared civil disorder believing it produced anarchy, giving their highest regard to peace, harmony and order.[55]

In order to reinforce order, society's class boundaries, which were most obvious in the courts where advantages and disadvantages based on class were convention, were turned into legislation.[55] Status, and the pursuit of status through wealth and the accumulation of possessions, was the pattern of Roman life.[56] Piety equaled loyalty to family, class, city and emperor, and it was demonstrated by loyalty to the practices and rituals of the old religious ways not by the individual faith of Christianity.[56]

Christianity was mostly seen as odd, but also as disruptive, and by some, as a threat to "Romanness".[57] While Christianity was largely tolerated, it was also persecuted, though persecution tended to be localized actions by mobs and governors until Christianity reached a critical juncture in the mid-third century.[58] In 250, Decius made it a capital offence to refuse to make sacrifices to Roman gods. The majority of scholars see Decius' decree as a requirement applied to all the inhabitants of the Empire, but they also see it as possible he intended it as an anti-Christian measure.[59] Still, Decius did not outlaw Christian worship.[60] Valerian pursued similar policies later that decade. These were followed by a 40-year period of tolerance known as the "little peace of the Church". The last and most severe official persecution, the Diocletianic Persecution, took place in 303–311.[61]

Geographical spread

Beginning with less than 1000 people, by the year 100, Christianity had grown to perhaps one hundred small household churches consisting of an average of around seventy (12–200) members each.[62] It achieved critical mass in the hundred years between 150 and 250 when it moved from fewer than 50,000 adherents to over a million.[63] This provided enough adopters for its growth rate to be self-sustaining.[63][64]

Rodney Stark estimates that Christians made up around 1.9% of the Roman population in 250.[65] Scholars generally agree there was a significant rise in the absolute number of Christians in the third century.[66] Stark, building on earlier estimates by theologian Robert M. Grant and historian Ramsay MacMullen, estimates that Christians made up around ten percent of the Roman population by 300.[65]

In these early centuries, Christianity spread beyond the Roman Empire as well as within it. Armenia, Persia (modern Iraq), Ethiopia, Central Asia, India and China have evidence of early Christian communities.[67] Robert Louis Wilken writes that there is first hand evidence of Christian community in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and of the Syriac speaking church in Baghdad commissioning a bishop to send to Tibet.[68] By the mid-sixth century a merchant-traveler wrote of his discovery of fully formed Christian communities in Malabar on the southwestern coast of India, and on Socotra an island in the Arabian Sea. (These had originally been commissioned by the church in Persia.)[69] Georgia, where Christianity arrived before the third century, was North of Armenia. Two bishops from Georgia attended the Council of Nicaea in 325.[70][note 3]

In these early centuries, Christianity grew as individuals were drawn to the faith and instructed, often beginning with a King and Queen.[72]

Asia Minor and Achaea

Christine Trevett writes in the Cambridge History of Christianity that "Asia Minor and Achaea were nurseries for Christianity."[73] Christian churches grew within cities mentioned in the New Testament like Athens, Corinth, Ephesus, and Pergamum where civic pride and diverse cultures proliferated.[73][note 4]

In the second and third centuries, conflicts over the degree and type of Christ's divinity and humanity emerged.[80] The belief in Jesus Christ as the incarnation of the pre-existent and creative 'logos' (word of god), held by many Christians of the east, fueled the later Arian controversy.[81]

In the Christian ‘mainstream’, the apostles, those who had known them, and the apostolic tradition were used as the theological basis for opposition.[82] By the end of the second century, catholic leaders were gathering formally to discuss major issues and form official statements of ‘orthodox’ Christian belief which included a ‘canon of truth’ and a ‘rule of faith’.[83] Trevett writes that "There was not just Christian diversity but a proud distinctiveness in Asia Minor. Its catholic leaders stood their ground, despite the claims and differing practices of Rome".[84]

Egypt

There is no archaeological evidence of Christianity in Egypt before the fourth century, however, Birger Pearson writes in the Cambridge History of Christianity that the literary evidence of Christianity's presence there before the fourth century is "massive".[85][note 5]

Egyptian Christianity began in Alexandria probably very early.[90] According to Pearson, "Writings that would eventually become part of the New Testament canon were brought to Egypt ... probably in the first century".[85][note 6] The most plausible explanation comes from papyrologist Colin Roberts who concludes that the earliest Egyptian ‘Christians’ were not a separate community but were instead an integral part of the Jewish community of Alexandria.[93]

_(14775178261).jpg.webp)

Jewish immigration into Egypt from Palestine had begun as early as the sixth century BC, and by the first century AD, the Jewish population in Alexandria numbered in hundreds of thousands.[94] With the coming of Roman rule in 30 BC, the situation of the Jews declined, leading to a pogrom against the Jews in 38 AD. In 115, diaspora Jews in Alexandria revolted. Under Trajan, this led to the virtual annihilation of the Alexandrian Jewish community in 117 AD.[92]

The revolt was also a crucial event for Christians.[93] Much of the literary legacy of the lost Jewish community was saved by Christians who treasured and preserved it, and this legacy heavily impacted their literary production.[93] From the first century on, countless Christian writings flowed into Alexandria from all over the Empire, and Alexandrian Christians were prolific in response.[95]

Gnosticism first appeared in Egypt in the second century.[96] According to Roberts, the early papyri provide no support for the view that Gnosticism was the earliest form of Christianity in Egypt.[93] Marcionite Christianity also came to Alexandria in the mid-second century.[96]

In Alexandria, Clement was a teacher and presbyter who wrote against gnosticism by distinguishing between ‘false’ knowledge and the 'true' knowledge that had come from the apostles.[97] Seen as the greatest scholar and theologian of the ancient church, Origen was one of the most prolific writers of antiquity.[98] Christians wrote of the church’s core apostolic faith as the same the world over. Pearson writes that, "The church inherited this claim ... from Judaism, which, ... was the only other religion in the history of Graeco-Roman religions to have this feature".[95]

Christian organization in Alexandria evolved following the model of the synagogue. Each Christian congregation had its own presbyter.[99] According to Pearson, "The writings of Clement and Origen attest to this evolution ‘from the Christian community to an institutional church’."[100]

In this early period, Christian religion expanded beyond Alexandria into the interior of Egypt where it was influenced by native Egyptian culture and language. This produced a distinctive Coptic Christianity which is still active in the twenty-first century.[91]

Monasticism played a greater role in Egyptian Christianity than in any other regional church.[101] Pearson says that "Roger Bagnall is probably right" that Christians were already a majority in Egypt by the time of the death of Constantine in 337.[102]

According to Pearson: "By the end of the third century, the Alexandrian church was at least as influential in the east as the Roman church was in the west".[103]

Syria and Mesopotamia

.svg.png.webp)

Christianity in Antioch is mentioned in Paul's epistles written before 60 AD, and scholars generally see Antioch as a primary center of early Christianity.[104][note 7] The Chronicle of Edessa records a flood in Edessa, in the year 201, that destroyed ‘the temple of the church of the Christians’. This demonstrates there was a community in Edessa that was large enough by the third century to have a building worth noting.[106]

Harvey attests that "Eusebius knew an independent tradition linking Thomas to the conversion of Edessa..." (HE 1.3; 2.1; 3.1). Edessa proudly held the relic of Thomas’ bones – attested both by Ephrem and by the western pilgrim Egeria, who saw them on her visit to the city in April 384". Thomas was also associated with the founding of Christianity in Mesopotamia and India. [107]

Syria preserved the earliest known collection of Christian hymns, the Odes of Solomon, which Harvey notes use "powerful feminine imagery ... for the Holy Spirit, a frequent characteristic of Syriac writings prior to the fifth century".[108] Especially prominent are images of healing and bodily wholeness, which is one of the most pervasive and enduring themes of Syrian Christianity throughout its regions and across its various doctrinal forms.[106]

The prophet Mani was born in Persian Mesopotamia in 216, and his religion, Manichaeism, was popular in Syria for some centuries.[109][110] Zoroastrian opposition led to Mani's imprisonment and death in 276.[110]

Christians in this region had little, if any, direct experience with persecution before the fourth century.[111] By the turn of the fourth century, foundation legends began to appear. "Most famous was the legendary correspondence between Jesus and king Abgar Ukkama (‘the Black’) of Edessa. The story is best known in the version of Eusebius (HE 1.13), in which the apostle Thaddaeus, one of the seventy, is sent by Thomas to convert the kingdom of Edessa. Eusebius claims to have translated this correspondence directly from Syriac into Greek (HE 1.13.6–10)".[112]

Gaul

Founding members of Christianity in Gaul were probably from the already established communities in the East and Rome.[113]

Most of what is known of early Christianity in Gaul comes from the Letter of the churches of Vienne and Lyons concerning the persecution of Christians under Marcus Aurelius.[114] Doubts have been raised about the letter's authenticity, but it is generally accepted.[115] Eusebius gives two dates for the persecution ten years apart, the seventh year of Marcus Aurelius’ reign (166–167), and the seventeenth year (177), which is the date most widely accepted.[114] The letter was written in response to the rise of Montanism in Asia and Phrygia.[116] The letter specifically refers to the martyrdom of eleven Christians from Vienne and Lyons, although later martyrologies record 49 names.[117] In the letter, grisly details of the suffering and martyrdoms are interpreted theologically.[118]

Irenaeus, who became bishop of Lyons after the martyrdom of Pothinus, is the most likely author of the letter, but his primary work, written between 174 and 189 is "Detection and refutation of gnosis falsely so-called", (usually known by its Latin title Adversus haereses).[117]

Irenaeus describes how, in his early youth, he had known Polycarp, the bishop of the church in Smyrna. This connection with Polycarp was important for Irenaeus: he emphasises that Polycarp had been appointed bishop of Smyrna by the apostles themselves and spoke often about his discussion with John and others who had seen the Lord. Irenaeus thus brought with him to Gaul a living connection with the age of the apostles...[119]

There is nothing more of Christianity in Gaul until the beginning of the 4th century excepting one inscription, which can possibly be dated to the early 3rd century, from the cemetery of Saint Pierre l’Estrier in Autun.[120]

During the first two and a half centuries, Christianity in Gaul is characterized by diversity.[121]

North Africa

.svg.png.webp)

The origins of Christianity in North Africa are unknown, but most scholars connect it to the Jewish communities of Carthage.[122]

The Pauline letters were available in Latin by 180 (M. Scil. 12), and the remainder of scripture by c.250, and African Christians had all the biblical books in Latin except James, 2 Peter and 2 and 3 John.[122] North Africa formed church doctrines on the Trinity, the nature of the soul, biblical interpretation, the nature of the church itself, and roles for women, but did this mostly by solving practical problems rather than theological ones.[123] Women prophets were generally respected in the church, however, Tertullian opposed leadership roles for women. It's possible that is due to his personal association of women’s leadership with gnostic theology, since he stood alone in that opposition.[123] He was at odds with African trends and with members of the New Prophecy outside Africa.[124]

Standards of conduct, especially with regard to sexual mores, were stricter than that of the surrounding culture for both men and women.[125] Africans strongly defended the re-baptism of those who failed, but they did not break communion with Romans who did not re-baptise.[126] This 'collegiality' was a hallmark of African church governance in its first three centuries. Bishops might threaten excommunication but did not actually break communion.[127] There were internal issues in the church that produced division, but in spite of any and all disagreements, Tertullian and Cyprian both proclaimed the unity of the church.[128]

While there is no accurate count of the persons martyred in Africa, Christians were persecuted intermittently from 180 until 305.[129][note 8] In the first three centuries, the most serious threats occurred under Emperors Decius and Valerian when the requirement to sacrifice to the gods was universally enforced and documented.[131] Some Christians tried to acquire the necessary documents through proxies or bribery, while some went into exile, and others were executed. Many simply complied.[131] These were condemned by rigorists in the church as lapsi in contrast to the stantes who stood firm. Problems were created when the lapsi later tried to rejoin the church.[131]

In 253, a new persecution began under Valerian (r. 253–9) aimed at high-ranking clergy. Christian leaders were required to sacrifice and stop all Christian assemblies, while all Christians were forbidden to have their own cemeteries.[132] Maureen Tilley in the Cambridge History of Christianity writes that "Some clergy were sentenced to the imperial mines (Cypr. Ep. 76–9). During the summer of 256, the higher clergy became subject to the death penalty; upper-class men lost their status and property and, if they persisted in the faith, were also executed. Upper-class women were exiled and their property seized (Cypr. Ep. 80)."[132] Cyprian was arrested, tried and executed in 258.[132]

After Valerian’s death, there were four decades of relative peace. Then, according to Tilley, "in the 290s, the military began to execute soldiers, such as Maximilian of Theveste and Marcellus of Tingis, for refusal to serve after conversion".[133]

Martyrs reinforced Christian identity as something that included resistance to state authority when necessary.[133]

Church hierarchy

Gerd Theissen writes that church leadership in primitive Christianity transformed from itinerant preaching into resident leadership (those located in a particular community over which they exercised leadership) laying the foundation for the church structure that followed.[134]

Episkopoi were overseers – bishops – and presbyters were generally elders or priests. Deacons served. However, the terms were sometimes used interchangeably.[135]

Following the administrative pattern set by the Empire, the territory administered by a bishop came to be known by its ordinary civil term: diocese.[136] The bishop's actual physical location within his diocese was his "seat", or "see".[137]

A study by Edwin A. Judge, social scientist, shows that a fully organized church system had evolved before Constantine and the Council of Nicea in 325.[4]

New Testament

During the rise of Christianity in the first century AD, new scriptures were written in Koine Greek. Christians eventually called these new scriptures the "New Testament", and began referring to the Septuagint as the "Old Testament".[138] New Testament books already had considerable authority in the late first and early second centuries.[139] Even in its formative period, most of the books of the NT that were seen as scripture were already agreed upon. Linguistics scholar Stanley E. Porter says "evidence from the apocryphal non-Gospel literature is the same as that for the apocryphal Gospels – in other words, that the text of [most of] the Greek New Testament was relatively well established and fixed by the time of the second and third centuries".[140]

When discussion of canonization began, there were disputes over including some texts, such as the Epistle to the Hebrews, the Epistle of James, the First and Second Epistle of Peter, the First Epistle of John, and the Book of Revelation.[141][142] The list of books included in the canon of the early Catholic Bible was established by the Council of Rome in 382, followed by those of Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397.[143]

Spanning two millennia, the Bible has become one of the most influential works ever written, having contributed to the formation of Western law, art, literature, literacy and education.[144][145]

Church fathers

The earliest orthodox writers of the first and second centuries, outside the writers of the New Testament itself, were first called the Apostolic Fathers in the sixth century.[146] The title "Church Father" is used by the church to describe those who were the intellectual and spiritual teachers, leaders and philosophers of early Christianity.[147] Writing from the first century to the close of the eighth, they defended their faith, wrote commentaries and sermons, recorded the Creeds, church history, and lived exemplary lives.[148][note 9]

Jewish Christianity

Christianity originated in 1st-century Judea as a sect of apocalyptic Jewish Christians within Second Temple Judaism.[1][158] In the early first century, the temple in Jerusalem was still central to Judaism, though synagogues were also established as institutions for prayer and the reading of Jewish sacred texts.[159]

While there is evidence supporting the presence of Gentiles even in the earliest Christian communities (Acts 10), most early Christians, such as the Ebionites, remained actively Jewish.[158]

The early Christian community in Jerusalem, led by James the Just, brother of Jesus, was singularly influential.[160][161] According to Acts 9,[162] they described themselves as "disciples of the Lord" and [followers] "of the Way", and according to Acts 11,[163] a settled community of disciples at Antioch were the first to be called "Christians". [note 10]

Gentile Christianity

Christianity grew apart from Judaism for several reasons. Jerusalem fell to the Romans, and the Temple was destroyed in 70 AD.[168] Christianity did not support the Jews in their rebellion against Rome and blamed Judaism's rejection of Jesus for the Temple's destruction.[164][2]

The fourth-century church fathers Eusebius and Epiphanius of Salamis cite a tradition that, before the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 the Jerusalem Christians had been warned to flee to the mountains in the north (Mark 13:14), but instead they went to Pella in the East in the region of the Decapolis across the Jordan River, although the historicity of Christians in this location is also heavily debated.[169][170]

Heresey and orthodoxy

Emerging Christianity embraced some theological, ecclesiological and regional diversity, but ‘insider-outsider’ boundaries were still being determined in this period.[171] ‘Orthodoxy’ was not the exclusive property of one group, and many of the ideas in Gnostic or New Prophecy/Montanist or Marcionite teachings overlapped with ideas from the 'norm'.[84] Defining ‘orthodoxy,’ therefore, took time.[172] According to Christine Trevett, "the lines of demarcation were not solid", making it questionable whether orthodoxy and heresy can even be spoken of as real categories of thought before the council of Nicaea.[171]

The Bauer-Ehrman thesis is the prevailing paradigm in popular American culture concerning varieties of Christianity, but it is not agreed upon by the majority of scholars around the world.[173] The thesis states that Christianity of the second and third centuries was highly diverse; that its heretical forms were early, widespread, and strong; and that orthodoxy came later when the Roman church enforced conformity to its views.[174][175]

Heresy was first to arrive in some regions, however, there is also unambiguous evidence in other regions (such as Ephesus and western Asia Minor) that heresy was neither early nor strong, that it was preceded by orthodoxy, and that orthodoxy was numerically larger.[176][93] There is also the problem that a powerful, united, Roman church capable of enforcing its will did not exist in this period.[177][178]

The earliest writers emphasized the unity of Christianity.[128][95] 'Core beliefs' on doctrine, ethos, fellowship and community as well as many doctrinal tenets such as monotheism, Jesus as Christ and Lord, and the Gospel as a message concerning salvation were based on apostolic authority.[179][82][97]

Theology of Early Christianity

Early Christian communities were highly inclusive in terms of social stratification and other social categories.[180] Paul's understanding of the innate paradox of an all powerful Christ dying as a powerless man created a new understanding of power and a new social order unprecedented in classical society.[181][note 11]

Historian Raymond Van Dam says conversion produced "a fundamental reorganization in the ways people thought about themselves and others".[187] Women were able to negotiate an expanded role in society that was not available in the current forms of Judaism or Romanism.[188]

Prior to Christianity, the wealthy elite of Rome mostly donated to civic programs designed to elevate their status.[189][190][191] Christians, on the other hand, offered last rites to the dying, buried them, distributed bread to the hungry, and showed the poor great generosity.[192][193][note 12]

An important cultural shift took place in the way Christians buried one another: they gathered unrelated Christians into a common burial space, then "commemorated them with homogeneous memorials and expanded the commemorative audience to the entire local community of coreligionists" thereby redefining the concept of family.[194][195]

Classics scholar Kyle Harper says "Christianity not only drove profound cultural change, it created a new relationship between sexual morality and society... [replacing the] ancient system where social and political status, power, and the transmission of social inequality to the next generation scripted the terms of sexual morality. ...There are risks in over-estimating the change in old patterns Christianity was able to begin bringing about; but there are risks, too, in underestimating Christianization as a watershed".[196]

Late antiquity to Early Medieval Christianity (325–600)

According to Michele R. Salzman, fourth century Empire featured sociological, political, economic and religious competition, producing tensions and hostilities between a large number of various groups. Christians described themselves as triumphant and focused on suppressing heresy.[197]

Influence of Constantine

Averil Cameron, in the Cambridge History of Christianity, writes that, "The reign of Constantine ... was momentous for Christianity".[198] The Roman Emperor Constantine I became the first Christian emperor in 313, (though he did not become sole emperor until after defeating Licinius the emperor in the East in 324).[199] In 313, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, (which had been the policy of Licinius), expressing tolerance for all religions, thereby legalizing Christian worship.[199] Christianity did not become the official religion of the empire under Constantine, but he took steps to support and protect it that became vitally important in the history of Christianity.[200]

He established equal political footing for Christian clergy by granting them the same immunities pagan priests had long enjoyed.[200] He gave bishops an important privilege by granting them judicial power. [201] He initiated a momentous precedent for Christian rulers by intervening in church disputes.[202][203][note 13] Bishops were grateful to Constantine, (instead of rejecting state authority), and this attitude proved to be critical to the further growth of the church.[201]

Constantine's church building was one of his most influential steps supporting the spread of Christianity.[201] He devoted imperial and public funds to his building program, endowed his churches with wealth and lands, and provided revenue for their clergy and upkeep.[204] Cameron explains that, "In a sense he was simply following the example set by his pagan predecessors ... Nevertheless his activities set a pattern for others, and by the end of the fourth century every self-respecting city, however small, had at least one church".[204]

How much Christianity Constantine personally adopted is difficult to discern.[7][205] Constantine was over 40, had most likely been a traditional polytheist, and according to historian Peter Brown, was a savvy and ruthless politician when he declared himself a Christian.[206] His religious belief has always been a matter for speculation, but as Cameron says, it is clear that whatever zeal he held for the church "did not absolve him from the harsh realities of power";[207] "Constantine was a pragmatist".[208]

While he did pursue public policies that were favorable to Christianity, there are few obviously Christian elements in the surviving laws of Constantine.[202][209] Contemporary scholars are in general agreement that Constantine did not support the suppression of paganism by force.[210][211][212][213][note 14]

Constantine did apparently author several laws that threatened and menaced any who continued to practice sacrifice.[241][242][note 15] There is no evidence of any of the horrific punishments ever being enacted.[246] There is no record of anyone being executed for violating religious laws before Tiberius II Constantine at the end of the sixth century (574–582).[247] Constantine did not stop the established state support of the traditional religious institutions, nor did society substantially change its pagan nature under his rule.[238]

Yet Cameron still concludes that Constantine brought the Christian church and the Roman state together "in a completely new way, and in this his reign was fundamental for subsequent history".[248]

Monasticism and hospitals for the poor

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

Christian monasticism grew from roots in certain strands of Judaism and views in common with Graeco-Roman philosophy and religion, and was modeled upon Scriptural examples and ideals such as John the Baptist who was seen as an archetypical monk.[249][250] Christian monasticism emerged separately from these other previous forms in the third century; by the 330's, it had become a significant social and religious force.[249] By the fifth century, Christian monasticism was a dominant force in all areas of late antique culture.[251][note 16]

Monastic communities were, in general, devoted to prayer, moderate self denial, manual labor and mutual support.[255] Early monastics also developed a health care system which allowed the sick to remain within the monastery as a special class afforded special benefits and care.[256] This destigmatized illness and formed the basis for future public health care. The first public hospital (the Basiliad) was founded by Basil the Great in 369.[257]

Central figures in the development of monasticism were Basil in the East and, in the West, Benedict, who created the Rule of Saint Benedict, which would become the most common rule throughout the Middle Ages and the starting point for other monastic rules.[258]

Arianism, Nestorianism, Monophysites and the first ecumenical councils

During Antiquity, the Eastern church produced multiple doctrinal controversies that attempted to define how, and when, the Christ became both human and divine.[259] These were often dubbed heresies by their opponents, and during this age, the first ecumenical councils were convened to deal with them.

The first, and most influential, was between Arianism and orthodox trinitarianism. Arianism argued that the Christ was divine, but was a creation, and was therefore not equal to the Father. This spread throughout most of the Roman Empire from the 4th century onwards.[note 17][note 18] The First Council of Nicaea (325) and the First Council of Constantinople (381) resulted in a condemnation of Arian teachings as heresy and produced the Nicene Creed. Arianism was eventually eliminated by orthodox opposition and empirical law, though it remained popular for some time.[260][261]

The Third, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth ecumenical councils are generally considered the most important of the remaining councils, and all are characterized by Nestorianism vs. Monophysitism.[262] The West came down firmly on the side of stressing the humanity of Christ and the reality of His moral choices. To preserve His Divine nature, the unity of His person was described in a looser way than in Eastern theology. It was primarily this difference which was at the heart of the Nestorian controversy.[263]

The resulting schism created a communion of churches, including the Armenian, Assyrian, and Egyptian churches.[264] By the end of the 5th century, the Persian Church had become independent of the Roman Church eventually evolving into the modern Church of the East.[265] Though efforts were made at reconciliation in the next few centuries, the schism remained permanent, resulting in what is today known as Oriental Orthodoxy. Most Christians in Asia belonged to branches of the Nestorian church from the end of the fifth century into the thirteenth century.[266]

Jews

In the fourth century, Augustine argued that the Jewish people should not be forcibly converted or killed, but that they should be left alone. Until the thirteenth century, that left the Jews in an odd position in society as both protected and condemned by Christian teaching. According to Anna Sapir Abulafia, most scholars agree that Jews and Christians in Latin Christendom lived in relative peace with one another until the thirteenth century.[267][268] Scattered violence toward Jews occasionally took place during riots led by mobs, local leaders, and lower level clergy without the support of church leaders who generally followed Augustine's teachings.[269] [270]

Supersessionism

Sometime before the fifth century, the church took its universally held traditional interpretation of Revelation 20:4–6 (Millennialism), and augmented it with supersessionism.[271][272] Millennialism is the hope of the thousand-year reign of the Messiah on earth, centered in Jerusalem, ruling with the redeemed Israel.[273] Supersessionism is a historicized and allegorized version of this which sees the church as the metaphorical Israel, thereby eliminating the Jews altogether.[274]

Supersessionism is significant because "It is undeniable that anti-Jewish bias has often gone hand-in-hand with the supersessionist view".[275] Many Jewish writers trace anti-semitism, and the consequences of it in World War II, to this particular doctrine among Christians.[276][277] Supersessionism has been a part of Christian thought for much of Christian history.[278] However, it has never been an official doctrine and has never been universally held.[273]

Christianity as a state religion

The first countries to make Christianity their state religion were Armenia (301), Georgia (4th century), Ethiopia and Eritrea in 325.[279][280][281]

Concerning the Roman Empire, Theodosius I (347–395) was described, after his death, by fourth century Christian writers as the emperor who established Nicene Christianity as the official religion of the empire. Contemporary scholars see this more as part of the narrative those authors created in their battle against Arianism than they see it as actual history.[282][283][284][285]

Cameron explains that, since Theodosius's predecessors Constantine, Constantius, and Valens had all been semi-Arians, it fell to the orthodox Theodosius to receive credit for the triumph of Christianity from Christian literary tradition.[286][note 19]

Cameron has concluded there is no solid evidence that a universal ban on paganism in the Roman empire ever existed.[296] Some twentieth century scholars thought a universal ban on paganism, and the establishment of Christianity as the "official" religion of the empire, (though never explicitly stated), could be implied from Theodosius' law of November 392.[293][297][298] However, this law was sent only to Rufinus in the East;[299] it is concerned solely with private domestic sacrifice, and bans the magic and idolatry magic associated with it.[300][301] It makes no mention of Christianity.[302][303] Sozomen, the Constantinopolitan lawyer, wrote a history of the church around 443 where he evaluates the law of 392 as having had only minor significance at the time it was issued. Sacrifice had mostly ended by the mid-300s.[304][305]

Peter Brown has written that, "it is impossible to speak of a Christian empire as existing before Justinian I" in the sixth century.[306]

Christianity in the Roman Africa province

Informal primacy was exercised by the Archdiocese of Carthage, a metropolitan archdiocese also known as "Church of Carthage". The Church of Carthage thus was to the Early African church what the Church of Rome was to the Catholic Church in Italy.[307] Famous figures include Saint Perpetua, Saint Felicitas, and their Companions (died c. 203), Tertullian (c. 155–240),[308] Cyprian (c. 200–258), Caecilianus (floruit 311), Saint Aurelius (died 429), Augustine of Hippo (died 430), and Eugenius of Carthage (died 505).

In North Africa of the fourth century, a reaction to the reinstatement of Bishops who had fled during the persecution of Diocletian formed Donatism as a Christian sect that withdrew from Catholicism. It mainly flourished among the indigenous North African Berber population during the fourth and fifth centuries.[309][310][311] By the time Augustine became coadjutor Bishop of Hippo in 395, Donatists had been fomenting protests and street violence, refusing compromise, and attacking random Catholics without warning for decades. They often did serious and unprovoked bodily harm such as beating people with clubs, cutting off hands and feet, and gouging out eyes.[312]

Augustine began defending violence by the imperial authorities as a means of coercing the Donatists to repent, though he always opposed execution.[313][309] His authority on coercion was undisputed for over a millennium in Western Christianity, and according to Brown "it provided the theological foundation for the justification of medieval persecution".[314]

Barbarians

The integration of barbarian people into the Roman world of the fourth century transformed both Roman culture and the barbarians. One aspect of this change was religious. Beginning with the Goths around 369, various Germanic people adopted Christianity, and began to form into the distinct ethnic groups that would become the future nations of Europe.[315] Vandals converted shortly before they left Spain for northern Africa in 429.[316] Clovis I converted to Catholicism sometime around 498, founding what would eventually become the Carolingian Dynasty.[317]

In all cases, Christianization meant "the Germanic conquerors lost their native languages" as these languages became Latinized.[318] At least one historian of the time, Orosius, wrote that conversion made the barbarians milder and set limits on their "savagery".[319]

Early Middle Ages (476–842)

The Age of the monk

Historian Geoffrey Blainey writes that the Catholic Church in the period between the Fall of Rome (476 C.E.) and the rise of the Carolingian Franks (750 C.E.) was like an early version of a welfare state. "It conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor.[320][321]

Monasteries preserved classical craft and artistic skills while maintaining intellectual culture within their schools, scriptoria and libraries. As well as providing a focus for spiritual life, they functioned as agricultural, economic and production centers, particularly in remote regions.[322]

These early monasteries were models of productivity and economic resourcefulness, teaching their local communities animal husbandry, cheese making, wine making, and various other skills.[323] Medical practice was highly important and medieval monasteries are best known for their contributions to medical tradition. They also made advances in sciences such as astronomy, and St. Benedict's Rule (480–543) impacted politics and law.[321][324]

The formation of these organized bodies of believers distinct from political and familial authority, especially for women, gradually carved out a series of social spaces with some amount of independence thereby revolutionizing social history.[325]

Western missionary expansion

After the Fall of Rome in the late fifth century, the church gradually replaced the Roman Empire as the unifying force in Europe, providing what security there was, actively preserving ancient texts and literacy.[326][327]

Pope Celestine I (422–430) sent Palladius to be the first bishop to the Irish in 431, and in 432, Gaul supported St Patrick as he began his mission there.[328] Relying largely on recent archaeological developments, Lorcan Harney has reported to the Royal Academy that the missionaries and traders who came to Ireland in the fifth to sixth centuries were not backed by any military force.[328]

Recent archaeology indicates Christianity had become an established minority faith in some parts of Britain by the fourth century. It was largely mainstream, and in certain areas, was continuous.[329] Irish missionaries led by Saint Columba, went to Iona (from 563), and converted many Picts.[330] The court of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria, and the Gregorian mission who landed in 596 sent by Pope Gregory I and led by Augustine of Canterbury, did the same for the Kingdom of Kent.[331]

The Franks first appear in the historical record in the 3rd century as a confederation of Germanic tribes living on the east bank of the lower Rhine River. The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of Gaul (modern France and Belgium) were overrun by the Franks in the early 5th century. They were persecuted until the Frankish King Clovis I converted from Paganism to Roman Catholicism in 496.[332] Clovis I became the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler.[333]

A seismic moment

In 416, the Germanic Visigoths had crossed into Hispania as Roman allies.[334] They converted to Arian Christianity shortly before 429.[316] An important shift took place in 612 when the Visigothic King Sisebut declared the obligatory conversion of all Jews in Spain, contradicting Pope Gregory who had reiterated the traditional ban against forced conversion of the Jews in 591.[335] Scholars refer to this shift as a "seismic moment" in Christian history.[336]

Justinian I and Eastern influence

The Eastern Roman Empire, with its heartland in Greece and Asia Minor, became the Byzantine Empire after the fall of the Roman West.[337] With its autocratic government, stable farm economy, Greek heritage and Orthodox Christianity, the Byzantine Empire lasted until 1453 and the Fall of Constantinople.[259]

During Byzantium's first major historical period, from 476 to 641, its borders reached its furthest limits under the Emperor Justinian I.[338] In an attempt to reunite the empire, Justinian went to Rome to liberate it from barbarians leading to a guerrilla war that lasted nearly 20 years.[339]

After fighting ended, Justinian used a Pragmatic Sanction to assert control over Italy.[340] The Sanction effectively removed the supports that had allowed the Roman Senate to retain power.[341] Thereafter, the political and social influence of the Senate's aristocratic members disappeared, and by 630, the Senate ceased to exist. Its building was converted into a church.[341] Bishops stepped into civic leadership in the Senator's places.[341] The position and influence of the pope rose.[342]

Before the eighth century, the Pope as the 'Bishop of Rome,' had not had special influence over other bishops outside Rome and had not yet manifested as the central ecclesiastical power.[343] From the late seventh to the middle of the eighth century, eleven of the thirteen men who held the position of Roman Pope were the sons of families from the East. Before they could be installed, these Popes had to be approved by the head of State, the Byzantine emperor.[344]

This Byzantine papacy, along with losses to Islam and changes within Christianity itself, helped put an end to Ancient Christianity in the West.[345][346] This helped transform Christianity into its eclectic medieval forms.[347][348][349]

Byzantium

In terms of prosperity and cultural life, the Byzantine Empire of this period forms one of the high points of Christian history and Christian civilization,[350] and Constantinople remained the leading city of the Christian world in size, wealth, and culture.[351] There was a renewed interest in classical Greek philosophy and science, as well as an increase in literary output in vernacular Greek.[352] Byzantine art and literature held a preeminent place in Europe, and the cultural impact of Byzantine art on the West during this period was enormous and of long-lasting significance.[353]

Following a series of heavy military reversals against the Muslims, Iconoclasm emerged within the provinces of the Byzantine Empire in the early 8th century. In the 720s, the Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isaurian banned the pictorial representation of Christ, saints, and biblical scenes. In the Latin West, Pope Gregory III held two synods at Rome and condemned Leo's actions. The Byzantine Iconoclast Council, held at Hieria in 754 AD, ruled that holy portraits were heretical.[354] The iconoclastic movement destroyed much of the Christian Church's early artistic history. The iconoclastic movement was later defined as heretical in 787 AD under the Second Council of Nicaea (the seventh ecumenical council) but had a brief resurgence between 815 and 842 AD.

The Rise of Islam

The rise of Islam (600 to 1517) unleashed a series of military campaigns that conquered Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia by 650, adding North Africa and most of Spain by 740. Only the Franks and Constantinople were able to withstand this medieval juggernaut. Historians Matthews and Platt have written that, "At its height, the Arab Empire stretched from the Indus River and the borders of China in the East, to the Atlantic in the West, and from the Taurus mountains in the North to the Sahara in the South". Islam was the colossus of the Middle Ages.[355]

Rashidun Caliphate

Since they are considered "People of the Book" in the Islamic religion, Christians under Muslim rule were protected as dhimmi.[356][357] However, dhimmi are inferior to Muslims in Muslim culture, and Christian populations living in the lands invaded by the Arab Muslim armies between the 7th and 10th centuries AD suffered religious persecution, religious violence, forced conversion to Islam,[356][358] and martyrdom multiple times at the hands of Arab Muslim officials and rulers.[357][359][358][360] Many were executed under the Islamic death penalty for defending their Christian faith.[359][358][360]

Umayyad Caliphate

In general, Christians subject to Islamic rule were allowed to practice their religion with some notable limitations stemming from the apocryphal Pact of Umar. This treaty, supposedly enacted in 717 AD, forbade Christians from publicly displaying the cross on church buildings, from summoning congregants to prayer with a bell, from re-building or repairing churches and monasteries after they had been destroyed or damaged, and imposed other restrictions relating to occupations, clothing, and weapons.[361]The Umayyad Caliphate persecuted many Berber Christians in the 7th and 8th centuries AD, who slowly converted to Islam.[362]

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate was less tolerant of Christianity than had been the Umayyad caliphs.[357] Those such as Elias of Heliopolis, monks and prisoners of war who refused to convert were frequently killed.[363]

Nonetheless, Christian officials continued to be employed in the government, and the Christians of the Church of the East and the Jacobite Church were often tasked with the translation of Ancient Greek philosophy and Greek mathematics.[357][364][note 20]

High Middle Ages (800–1299)

The intense and rapid changes of the High Middle Ages are considered some of the most significant in the history of Christianity.[372]

Massacre and Renaissance

Saxon resistance to rule by the Carolingian kings was fierce and often targeted Christian churches and monasteries.[373] In 782 Saxons broke yet another treaty with Charlemagne, attacking the Franks when the king was away, dealing the Frankish troops heavy losses.[332][374][375] In response, the Frankish King returned, defeated them, and "enacted a variety of draconian measures" beginning with the massacre at Verden.[376] He ordered the decapitation of 4500 Saxon prisoners offering them baptism as an alternative to death.[377] These events were followed by the severe legislation of the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae in 785 which prescribes death to those that are disloyal to the king, harm Christian churches or its ministers, or practice pagan burial rites.[378] His harsh methods raised objections from his friends Alcuin and Paulinus of Aquileia.[379] Charlemagne abolished the death penalty for paganism in 797.[380]

Charlemagne also began the Carolingian Renaissance, a period of intellectual and cultural revival of literature, arts, and scriptural studies, a renovation of law and the courts, the founding of feudalism and the promotion of literacy.[381] Charlemagne himself could not read or write, but he admired it, so in order to address the problems of illiteracy, Charlemagne founded schools and attracted the most learned men from all of Europe to his court. They had many accomplishments including the development of lower case letters called Carolingian minuscule.[382] Beginning in the late 8th century under Charlemagne, renaissance continued into the 9th century under his son, Louis the Pious.[383]

Monastic reform

The church of this era had immense authority, but the key to its power were three monastic reformation movements that swept Europe in the tenth and eleventh centuries.[384][385] Prior to this, the church had become riddled with corruption, the buying and selling of church offices, and disregard for the sacraments.[386] The monks formed a new focus on reforming the world as well as themselves and this influenced the next 400 years of European history.[372]

Owing to its stricter adherence to the reformed Benedictine rule, the Abbey of Cluny became the leading centre of Western monasticism from the later 10th century.[387] The monastery at Cluny was established in 910 by the Benedictine Order without feudal obligations, allowing it to institute reforms.[386] The Cluniac spirit was a revitalising influence on the Norman Church, at its height from the second half of the 10th century through the early 12th century.[372]

The next wave of monastic reform came with the Cistercian movement. The first Cistercian abbey was founded in 1098, at Cîteaux Abbey. The keynote of Cistercian life was a return to a literal observance of the Benedictine rule, rejecting the developments of the Benedictines. Inspired by Bernard of Clairvaux, the primary builder of the Cistercians, they became the main force of technological advancement and diffusion in medieval Europe.[388]

A third level of monastic reform was provided by the establishment of the Mendicant orders. Beginning in the 12th century, the Franciscan Order was instituted by the followers of Francis of Assisi, and thereafter the Dominican Order was begun by St. Dominic. Ancient Christians had not thought of their movement in terms of social reform, whereas a "profound revolution in religious sentiment" led the new monastics to see their calling as actively working to reform the world.[389][390] Commonly known as "friars", mendicants live under a monastic rule with traditional vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience but they emphasize preaching, missionary activity, and education.

Dominicans came to dominate the new universities; they traveled about preaching against heresy, and eventually became notorious for their participation in the Medieval Inquisition, the Albigensian Crusade and the Northern crusades.[391] Christian policy denying the existence of witches and witchcraft would later be challenged by the Dominicans allowing them to participate in witch trials.[392][393]

Women

While the Middle Ages was a difficult time for most women, abbesses and female superiors of monastic houses were powerful figures whose influence could rival that of male bishops and abbots.[394][395]

The Gregorian Reform also impacted women in general by establishing new law requiring the consent of both parties before a marriage could be performed, a minimum age for marriage, and by codifying marriage as a sacrament.[396][397] That made the union a binding contract, making abandonment prosecutable with dissolution of marriage overseen by Church authorities.[398] Although the Church abandoned tradition to allow women the same rights as men to dissolve a marriage, in practice men were granted dissolutions more frequently than women.[399][400]

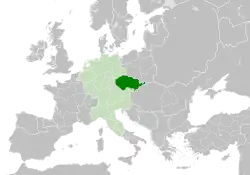

Spread of Christianity in Eastern Europe

Throughout central and eastern Europe, the Balkan Peninsula (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, and Slovenia), and the area north of the Danube (Poland, Hungary, Russia), Christianization and political centralization went hand in hand.[401][402] Local elites wanted to convert because they gained prestige and power through matrimonial alliances and participation in imperial rituals.[403][note 21]

.png.webp)

Significant missionary activity in this region only took place after Charlemagne defeated the Avar Khaganate several times at the end of the 8th century and the beginning of the ninth centuries.[404]

Two Byzantine brothers, Saints Constantine-Cyril and Methodius, played the key missionary roles in spreading Christianity to Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia territories beginning in 863.[405] They spent approximately 40 months in Great Moravia continuously translating texts, teaching students, and developing the first Slavic alphabet while translating the Gospel into the Old Church Slavonic language.[406][407] Old Church Slavonic became the first literary language of the Slavs and, eventually, the educational foundation for all Slavic nations.[406]

East West schism

Many differences between East and West had existed since Antiquity. Disagreements over whether Pope or Patriarch should lead the church, whether that should be done in Latin or Greek, whether priests must remain celibate and other points of doctrine such as the Filioque Clause which was added to the Nicene creed by the west, were intensified by cultural, geographical, geopolitical, and linguistic differences between East and West.[259][408][409] Eventually, this produced the East–West Schism, also known as the "Great Schism" of 1054, which separated the Church into Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[408]

Rise of universities

Modern western universities have their origins directly in the Medieval Church.[410][411][412][413][414] They began as cathedral schools then formed into self-governing corporations with charters.[415] Students were considered clerics.[416] This was a benefit that imparted legal immunities and protections. Schools were divided into faculties which specialized in law, medicine, theology or liberal arts (largely devoted to Aristotle), awarded degrees and held the famous quodlibeta theological debates amongst faculty and students.[415][417] The earliest were the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Oxford (1096), and the University of Paris where the faculty was of international renown (c. 1150).[418][419][420] Matthews and Platt say "these were the first Western schools of higher education since the sixth century".[415]

Investiture controversy

The Investiture controversy was the most significant conflict between secular and religious powers that took place in medieval Europe.[421] It began as a dispute in the 11th century between the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII concerning who would appoint bishops (investiture).[422] Ending lay investiture threatened to undercut the power of the Holy Roman Empire and the ambitions of the European nobility. But allowing lay investiture meant the Pope's authority over his own people was limited.[423][note 22] It took "five decades of excommunications, denunciations and mutual depositions...spanning the reign of two emperors and six popes" to settle the controversy in 1122.[426]

A similar controversy occurred in England between King Henry I and St. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, over investiture and episcopal vacancy.[427] The English dispute was resolved by the Concordat of London (1107).[426]

Crusades

Generally, the Crusades (1095–1291) refer to the European Christian campaigns in the Holy Land sponsored by the Papacy against Muslims in order to reconquer the region of Palestine.[428][429][430] The crusades produced cultural changes in both East and West fundamentally altering the political map of both. Crusades contributed to the decline of Byzantium and to the development of national identities in the newly forming European nations. The West's polarization and militarization increased its alienation from the East, and contact between Islamic and Christian cultures led to the exchange of medical knowledge, art and architecture and increased trade.[431][432]

The Holy Land had been part of the Roman Empire, and thus subsequently of the Byzantine Empire, until the Arab Muslim invasions of the 7th and 8th centuries. Thereafter, Christians had generally been permitted to visit the sacred places in the Holy Land until 1071, when the Seljuk Turks closed Christian pilgrimages and assailed the Byzantines, defeating them at the Battle of Manzikert. Emperor Alexius I asked for aid from Pope Urban II against Islamic aggression. He probably expected money from the pope for the hiring of mercenaries. Instead, Urban II called upon the knights of Christendom in a speech made at the Council of Clermont on 27 November 1095, combining the idea of pilgrimage to the Holy Land with that of defending the defenseless by waging a holy war against infidels.[433]

The First Crusade captured Antioch in 1099 and then Jerusalem. The Second Crusade occurred in 1145 when Edessa was taken by Islamic forces. Jerusalem was held until 1187 and the Third Crusade, after battles between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. The Fourth Crusade, begun by Innocent III in 1202, intended to retake the Holy Land but was soon subverted by the Venetians. When the crusaders arrived in Constantinople, they sacked the city and other parts of Asia Minor and established the Latin Empire of Constantinople in Greece and Asia Minor. Five numbered crusades to the Holy Land culminated in the siege of Acre of 1219, essentially ending the Western presence in the Holy Land.[434]

Jerusalem was held by the crusaders for nearly a century, while other strongholds in the Near East remained in Christian possession much longer. The crusades in the Holy Land ultimately failed to establish permanent Christian kingdoms. Islamic expansion into Europe remained a threat for centuries, culminating in the campaigns of Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century.

Baltic wars

When the Pope (Blessed) Eugenius III (1145–1153) called for a Second Crusade in response to the fall of Edessa in 1144, Saxon nobles in Eastern Europe refused to go.[435] From the days of Charlemagne (747–814), the free barbarian people around the Baltic Sea had raided the countries that surrounded them, stealing crucial resources, killing, and enslaving captives.[436] For the leaders of these Eastern European countries, (many of which were young countries with new monarchies), that meant subduing the Baltic area was more important to them than going to the Levant.[435] In 1147, Eugenius' Divini dispensatione, gave the eastern nobles crusade indulgences for the Baltic area.[435][437][438] The Northern, (or Baltic), Crusades followed, taking place, off and on, with and without papal support, from 1147 to 1316.[439][440][441]

These rulers saw holy war as a tool for territorial expansion, alliance building, and the empowerment of their own young church and state.[442] Taking the time for peaceful conversion did not fit in with these plans.[443] Conversion by these princes was almost always a result of conquest, either by the direct use of force, or indirectly, when a leader converted and required it of his followers.[444]

According to Fonnesberg-Schmidt, "While the theologians maintained that conversion should be voluntary, there was a widespread pragmatic acceptance of conversion obtained through political pressure or military coercion".[445] There were often severe consequences for populations that chose to resist.[446][447][448]

Political centralization through persecution

By 1150, European culture in the West was at a watershed. Kings and their nations were leaving the concept of Christendom behind and becoming more secular. Therefore they actively worked to centralize power into themselves and their newly forming nation-states.[391] Centralization was accomplished by taking legal, military, and social powers away from local level aristocrats, and local church leaders, who had traditionally held such powers. The state gained power by attacking these older kinship-based systems.[449]

The state redefined being a member of a minority (such as being Jewish or homosexual) as a threat to the social order. This allowed the state to proactively pursue the punishment of minorities by creating new laws and systems controlled by the state. Stereotyping, propaganda and the legal prosecution of minorities functioned socially and politically to legitimize the state and its authority and enable the transfer of power.[449] By 1200, local authority had been replaced by inquisition that was dependent upon state support.[450][note 23]

Moore writes that persecution became a functional tool of power and a core element in the social and political development of Western society.[460][461][462] By the 1300s, "The maintenance of civil order through legislated separation [segregation] and discrimination was part of the institutional structure of all European states ingrained in law, politics, and the economy".[463][455][464]

The church did not have the leading role in this but had a part in it through new canon laws.[465][466][467] According to the Oxford Companion to Christian Thought, during this period the religion that had begun by decrying the role of law as less than that of grace and love (Romans 7:6) developed the most complex religious law the world has ever seen, and in it, Christianity's concepts of equity and universality were largely overlooked.[468]

Law

Canon law of the Catholic Church (Latin: jus canonicum)[469] was the first modern Western legal system, and is the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the West,[470] predating European common law and civil law traditions.[471] Justinian I's reforms had a clear effect on the evolution of jurisprudence, and Leo III's Ecloga influenced the formation of legal institutions in the Slavic world.[472]

By the 1300s, most bishops and Popes were trained lawyers rather than theologians.[468]

Medieval Inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230) and the later Papal Inquisition (1230s–1240s), was a type of criminal court established and run by the Roman Catholic Church from around 1184. Inquisition placed an overseeing authority into the position of the "wronged party" who made the accusation against the suspect; then that same authority did the investigating and also judged their guilt.[473]

Dependent upon undependable secular support, inquisitions dealt largely, but not exclusively, with religious issues such as heresy.[473] Inquisition was not a unified single bureaucratic institution.[474][475] Jurisdiction was often local and limited; lack of support and outright opposition often obstructed it; and many parts of Europe had erratic inquisitions or none at all.[474]

Historian Christine Caldwell Ames writes that Dominican inquisitors saw their work as proving the "true faith" by interpreting Christ as the just persecutor of evil.[473] Ames calls this a "measured manipulation of the Christian faith" supported by circumstance, since heresy had exploded across Christendom in the 11th century.[476]

At the same time, inquisition was contested stridently through continuous and various kinds of opposition and complaint, both in and outside the church. Opponents charged heresy inquisitions with proving the Roman church was "unchristian" and "a destroyer of its gospel legacy, or even the real enemy of Christ".[477]

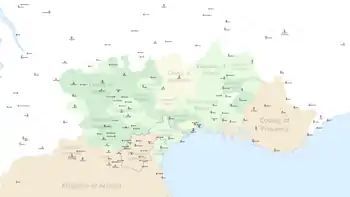

Albigensian Crusade

.svg.png.webp)

Cathars, also known as Albigensians, were the largest of the heretic groups that began reappearing in the High Middle Ages.[note 24] They were concentrated in the Languedoc region which was not then a part of France. After decades of having called upon secular rulers for aid in dealing with the Cathars and getting no response,[478] Pope Innocent III and the king of France, Philip Augustus, joined in 1209 in a military campaign that was, allegedly, about eliminating the Albigensian heresy.[479][480] Scholars disagree on whether war was determined more by the Pope or by King Philip and his proxies for his own purposes.[481][note 25]

"Kill them all"

The war began on 22 July 1209, in the first battle of the Albigensian Crusade, when mercenaries rampaged through the streets killing all they came across in what came to be known as the Massacre of Béziers. Some twenty years later, a story that historian Laurence W. Marvin calls apocryphal, arose about this event claiming the papal legate, Arnaud Amaury, was said to have responded: "Kill them all, let God sort them out". Marvin says it is unlikely the legate ever said any thing at all. "The speed and spontaneity of the attack indicates that the legate probably did not know what was going on until it was over".[486] Other scholars argue that the statement is not inconsistent with what was recorded by the contemporaries of other church leaders, or with what is known of Arnaud Amaury's character and attitudes.[487][488]

Denouement

Four years later, in a 1213 letter to Amaury, the pope rebuked the legate for his conduct in the war and called for an end to the campaign.[489] The campaign continued anyway. The Pope was then reversed by the Fourth Lateran council which re-instituted crusade status two years later in 1215; afterwards, the Pope removed it yet again.[490] Throughout the rest of the campaign, Innocent vacillated unable to make up his mind if the crusade had been right; he sometimes took the side favouring crusade then sided against it.[491]

By the end of the campaign, 16 years later, the campaign no longer had the status of a crusade nor were its fighters rewarded with dispensations. The army had seized and occupied the lands of nobles who had not sponsored Cathars but had been in the good graces of the church; Albigensia thereby became southern France. Catharism continued for another hundred years (until 1350).[492][493]

Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance (1300–1564)

Papal monarchy

The popes of the fourteenth century worked to amass power into the papal position, building what is often called the papal monarchy.[494][495] This was accomplished partly through the reorganization of the ecclesiastical financial system. The poor had previously been allowed to offer their tithes in goods and services, but these popes revamped the system to only accept money. A steady cash flow brought with it the power of great wealth. The papal states were thereafter governed by the pope in the same manner the secular powers governed. The pope became a pseudo-monarch.[494]

These fourteenth century popes were greedy and politically corrupt, so that pious Christians of the period became disgusted, leading to the loss of papal prestige.[494][496][note 26] Devoted and virtuous nuns and monks became increasingly rare. Monastic reform had been a major force in the High Middle Ages, but it is largely unknown in the Late Middle Ages.[498]

People living during the fourteenth century experienced plague, famine and war that ravaged most of the continent; there was social unrest, urban riots, peasant revolts and renegade feudal armies, and this was in addition to the religious changes often forced upon them by their new monarchies. They faced all of this with a church unable to provide much moral leadership as a result of its own internal conflict and corruption.[499]

The church reached its low point in the early 1400s when there were three different men claiming to be the rightful Pope.[500][494]

Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism

In 1309, Pope Clement V moved to Avignon in southern France in search of relief from Rome's factional politics.[494] Seven popes resided there in the Avignon Papacy until 1378.[501] Troubles grew while the prestige and influence of Rome decreased without a resident pontiff, and in 1377 Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome. After his death, the papal conclave met in 1378 in Rome and elected an Italian Urban VI to succeed Gregory.[494] The French cardinals did not approve. They held a second conclave electing Robert of Geneva instead. This began the Western Schism.[500][494]

Different secular leaders threw their support behind one or the other. Papal authority declined. In 1409, both sets of cardinals called the Pisan council electing a third pope and calling on the other two to resign, but they refused, leaving the church with three popes. The Council of Constance (1414–1418), called by the Holy Roman Emperor, finally resolved the conflict by electing Pope Martin V to replace the rest.[494]

In 1418, the Papacy regained control of the church, consolidated the Papal States and focused on the pursuit of power.[502] During this time, wealthy Italian families secured episcopal offices for themselves. The individuals who became Pope Alexander VI and Pope Sixtus IV were known for ignoring the moral requirements of their position. Pontiffs such as Julius II often waged campaigns to protect and expand their domains, and popes spent lavishly pursuing personal grievances, private luxuries and public works.[503]

Criticism of the Catholic Church's abuses and corruption

John Wycliffe, an English scholastic philosopher and Christian theologian best known for denouncing the abuses and corruption of the Catholic Church, was a precursor of the Protestant Reformation.[504] He emphasized the supremacy of the Bible and called for a direct relationship between God and the human person, without interference by priests and bishops.[504] The Lollards, a Proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of Wycliffe, played a role in the English Reformation.[504][505][506][507] Jan Hus, a Czech Christian theologian based in Prague, was influenced by Wycliffe and spoke out against the abuses and corruption he saw in the Catholic Church.[508] His followers became known as the Hussites, a Proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.[508][504] He was a forerunner of the Protestant Reformation,[508][504] and his legacy has become a powerful symbol of Czech culture in Bohemia.[509] Both Wycliffe and Hus were accused of heresy and subsequently condemned to the death penalty for their outspoken views about the Catholic Church.[510][508][504]

Renaissance and the Catholic Church

High Renaissance was the most brilliantly creative period of western history, and it was the Popes who became the leading patrons of the new style, and the Church which commissioned and supported such artists as Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Bramante, Raphael, Fra Angelico, Donatello, and Leonardo da Vinci.[502]

Scholars of the Renaissance created textual criticism which revealed writing errors by medieval monks and exposed the Donation of Constantine as a forgery. Popes of the Middle Ages had depended upon the document to prove their political authority.[511]

Catholic monks developed the first forms of modern Western musical notation leading to the development of classical music and all its derivatives.[512]

Fall of Constantinople

In 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire. The flight of Eastern Christians from Constantinople, and the Greek manuscripts they carried with them, is one of the factors that prompted the literary renaissance in the West.[513]

The Ottoman government followed Islamic law when dealing with the conquered Christian population. The Church's canonical and hierarchical organization were not significantly disrupted and its administration continued to function.

.jpg.webp)