Fourth television network

In American television terminology, a fourth network is a reference to a fourth commercial broadcast (over-the-air) television network, as opposed to the Big Three television networks that dominated U.S. television from the 1950s to the 1980s: ABC, CBS and NBC.

When the U.S. television industry was in its infancy in the 1940s, there were four major full-time television networks that operated across the country: ABC, CBS, NBC and the DuMont Television Network. Never able to find solid financial ground, DuMont ceased broadcasting in August 1956. Many companies later began to operate television networks which aspired to compete against the Big Three. However, between the 1950s and the 1980s, none of these start-ups endured and some never even launched. After decades of these failed "fourth networks", many television industry insiders believed that creating a viable fourth network was impossible. Television critics also grew jaded, with one critic placing this comparison in the struggles of creating a sustaining competitor to the Big Three, "Industry talk about a possible full-time, full-service, commercial network structured like the existing big three, ABC, CBS and NBC, pops up much more often than the fictitious town of Brigadoon."[1]

The first lasting attempt at a fourth network as DuMont went into decline was the non-commercial Educational Television and Radio Center (ETRC). Founded in 1953, it slowly grew into the National Educational Television (NET) network, and was superseded by PBS in 1970. The October 1986 launch of the Fox Broadcasting Company was met with ridicule; despite the industry skepticism and initial network instability, the Fox network eventually proved profitable by the early 1990s, becoming the first successful fourth network and eventually surpassing the Big Three networks in the demographics and overall viewership ratings by the early 2000s.

Background

In the 1940s, four television networks began operations by linking local television stations together via AT&T's coaxial cable telephone network. These links allowed stations to share television programs across great distances, and allowed advertisers to air commercial advertisements nationally. Local stations became affiliates of one or more of the four networks, depending on the number of licensed stations within a given media market in this early era of television broadcasting. These four networks – the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), the American Broadcasting Company (ABC), and the DuMont Television Network – would be the only full-time television networks during the 1940s and 1950s, as in 1948, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) suspended approvals for new station construction permits. Although other companies – including Paramount Pictures (with the Paramount Television Network) and the Mutual Broadcasting System – announced network plans or began limited network operations, these companies withdrew from television after the first few years, or in the Paramount Television Network's case the service withered through attrition over the same span as did DuMont's, losing most of its programming by 1953 and ceasing operations in 1956.[2][3][4]

The FCC's "freeze," as it was called, was supposed to last for six months. When it was lifted after four years in 1952, there were only four full-time television networks. The FCC would only license three local VHF stations in most U.S. television markets. A fourth station, the FCC ruled, would have to broadcast on the UHF band. Hundreds of new UHF stations began operations, but many of these stations quickly folded because television set manufacturers were not required to include a built-in UHF tuner until 1964 as part of the All-Channel Act. Most viewers could not receive UHF stations, and most advertisers would not advertise on stations which few could view. Without the advertising revenue enjoyed by the VHF stations, many UHF station owners either returned their station licenses to the FCC, attempted to trade licenses with educational stations on VHF, attempted to purchase a VHF station in a nearby market to move into theirs, or cut operating costs in attempts to stay in business .

Since there were four networks but only three VHF stations in most major U.S. cities, one network would be forced to broadcast on a UHF outlet with a limited audience. NBC and CBS had been the larger networks, and the most successful broadcasters in radio. As they began bringing their popular radio programs and stars into the television medium, they sought – and attracted – the most profitable VHF television stations. In many areas, ABC and DuMont were left with undesirable UHF stations, or were forced to affiliate with NBC or CBS stations on a part-time basis. ABC was near bankruptcy in 1952; DuMont was unprofitable after 1953.

On August 6, 1956, DuMont ceased regular network operations; the end of DuMont allowed ABC to experience a profit increase of 40% that year, although ABC would not reach parity with NBC and CBS until the 1970s. The end of the DuMont Network left many UHF stations without a reliable source of programming, and many were left to become independent stations. Several new television companies were formed through the years in failed attempts to band these stations together in a new fourth network.

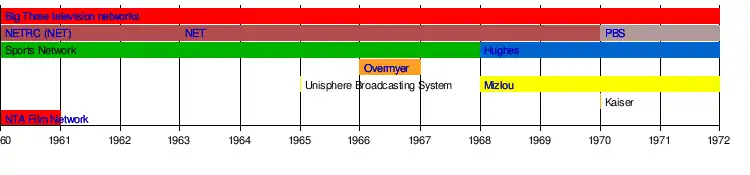

Early network timeline

Rationale

Some within the industry felt there was a need for a fourth network; that complaints about diversity in programming could be addressed by adding another network. "We need a fourth, a fifth, and a sixth network," one broadcaster stated.[1] While critics rejected "the nightly tripe being offered [to] the public on the three major networks," they were skeptical that a fourth network would offer better material: "[O]ne wonders if a new network lacking the big money already being spread three ways will be able to come up with tripe that is equal. Certainly a new network is not going to stress quality programming when the ratings indicate that the American public prefer hillbillies, cowboys and spies. A new network will have to deliver an audience if it is to attract the big spenders from the ranks of sponsors."[5]

Advertisers, too, called for the creation of a fourth network. Representatives from Procter & Gamble and General Foods, two of the largest advertisers in the U.S., hoped the competition from a fourth network would lower advertising rates on the Big Three.[6] Independent television producers, too, called for a fourth network after battles with the Big Three.[7]

Failed attempts

1950s

George Fox Organization network

George Fox, the president of the George Fox Organization, announced tentative plans for a television film network in May 1956. The plan was to sign 45 to 50 affiliate stations; each of these stations would have input in deciding what programs the network would air. Four initial programs – Jack for Jill, I'm the Champ, Answer Me This, and It's a Living – were slated to be broadcast; the programs would be filmed in Hollywood. However, only 17 stations had agreed to affiliate in May.[8] The film network never made it off the ground, and none of the planned programs aired.

Sports Network/Hughes Network

Also in 1956, Dick Bailey founded the Sports Network, a specialty television network which aired only sports programs. Millionaire Howard Hughes purchased the network in 1968, changing its name to the Hughes Television Network. Speculation abounded that Hughes would add non-sports programs to the lineup, launching a fourth network. One television critic speculated "If Hughes does have the exciting sports programs they can change viewer's dialing habits. If dialing habits are changed might he extend his network facilities to include nonsport programming? It would be one way, less costly and with far less of a risk, to start the illusionary fourth network."[9]

Despite the speculation, the Hughes Network never offered non-sports programs and never developed into a fourth major television network.

Mutual Broadcasting System

The Mutual Broadcasting System, as one of the four major radio networks that existed at the time, was considered a candidate for creating a fourth network. When Mutual came under the ownership of General Tire's General Teleradio along with five television stations, General Tire president Thomas F. O'Neil started putting a potential Mutual all-movie network together. Mutual purchased a large group of English films and paid $1.5 million for the right of unlimited play for two years of Roy Rogers and Gene Autry westerns.[10]

NTA Film Network

On October 15, 1956, National Telefilm Associates launched the NTA Film Network, a syndication service which distributed both films and television programs to independent television stations and stations affiliated with NBC, CBS or ABC; the network had signed agreements with over 100 affiliate stations.[11] The ad hoc network's flagship station was WNTA-TV (channel 13) in New York City.[12] The NTA Network was launched as a "fourth TV network," and trade papers of the time referred to it as a new television network.[13]

Despite this major fourth network effort, by 1961 WNTA-TV was losing money, and the network's flagship station was sold to the Educational Broadcasting Corporation that November. WNTA-TV became WNDT (later WNET), the flagship station of the National Educational Television network, a forerunner of PBS.[14] NTA network operations did not continue without a flagship station, although parent company National Telefilm Associates continued syndication services. Divorce Court was seen as late as 1969.

1960s

Pat Weaver's network

Pat Weaver, a former president of NBC, twice attempted to launch his own television network.[15] According to one source, the network would have been called the Pat Weaver Prime Time Network. Although the new network was announced, no programs were ever produced.[1]

Unisphere/Mizlou

In mid-1965, radio businessman Vincent C. Piano proposed the Unisphere Broadcasting System. The service would have operated for 2½ hours each night. However, Piano had difficulty signing affiliates; a year later, no launch date had been set, and the network still lacked a "respectable number of affiliates in major markets."[16]

The network finally launched under the name Mizlou Television Network in 1968, but the concept had changed. Like the Hughes Network, Mizlou only carried occasional sporting and special events. Despite developing a sophisticated microwave and landline broadcasting system, the company never developed into a major television network.

National Educational Television

Educational television (ETV) had existed since 1952, but was poorly funded. Only a few educational television stations existed during the 1950s. By 1962, 62 educational stations were in operation, most of which had affiliated with the non-commercial educational, National Educational Television (NET). That year, the U.S. Congress approved $32 million in funding for educational television, giving a boost to the non-commercial television network. Although at the 1962 revamp of the organization, NET was branded a "fourth network",[17] later historians have disagreed. McNeil (1996) stated, "in a sense, NET was less a true network than a distributor of programs to educational stations throughout the country; it was not until late 1966 that simultaneous broadcasting began on educational outlets."[18]

Overmyer/United Network

Millionaire Daniel Overmyer built a chain of five UHF stations during the mid-1960s. In late 1966, Overmyer announced plans for a new fourth network, named the Overmyer Network. The name was later changed to the United Network, but the network itself broadcast only for a single month, and aired only one program, The Las Vegas Show. The lack of reliable VHF stations helped kill the new, unprofitable network. Shortly after the network ceased operations, one critic called Overmyer/United a fiasco, and likened it to the earlier DuMont, NTA Film Network and Weaver network failures.[1]

Westinghouse or Metromedia

By the late 1960s, several fourth networks had vanished. Television set manufacturers were required to include a UHF tuner after 1964, and it was thought this would help UHF stations and any company hoping to band (mostly) UHF stations together in a fourth network. Two companies, Westinghouse and Metromedia, were floated in 1969 as possible fourth network entries.[1]

Westinghouse was the owner of several VHF stations and produced several series which aired on its stations and those owned by other companies; along with General Electric and GE subsidiary RCA, Westinghouse was also a cofounder of NBC in 1926 before both GE and Westinghouse had to divest their shares for antitrust reasons in 1930. (GE would later repurchase RCA in 1986.) However, Donald McGannon, president of Westinghouse, estimated it would take $200 million per year to operate a full-time television network and a modest news department. McGannon denied his company had full network aspirations.[1] Decades later, Westinghouse would later purchase CBS and adopt that network's identity while divesting itself of its legacy industrial businesses.

Metromedia, the successor company to the defunct DuMont Network, was a healthy chain of independent television stations. Although Metromedia "dabbled at creating a fourth network," the company was content with offering series to independent stations on a part-time basis, "nowhere near the conventional definition of a network."[19]

Kaiser Broadcasting

In September 1967, the Kaiser Broadcasting Company announced plans for live network operations by 1970.[16] Kaiser owned eight UHF television stations, most of them in large cities, including Los Angeles, Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston, and Detroit. The planned network never gained traction, and Kaiser sold the stations in 1977.

1970s

In the 1970s, the "occasional" television networks started to appear with greater frequency with Norman Lear, Mobil Showcase Network, Capital Cities Communications, and Operation Prime Time, all entering the fray along with Metromedia.[20] In 1978, SFM Media Service, which assisted with the Mobil Showcase Network, launched its own occasional network, the SFM Holiday Network[21] and the General Foods Golden Showcase Network.[22] SFM was a provider of ad hoc network as a service to other clients including Del Monte Foods.[21]

MGM Family Network

MGM Television entered the field with its self-proclaimed fourth network, the MGM Family Network (MFN), on September 9, 1973, with the movie The Yearling on 145 stations. MFN was created to fill the family programming void from 5:00 to 8:00 p.m. due to the implementation of the Prime Time Access Rule, using movies from the MGM library scheduled to air on one Sunday every two months. The premiere of MFN registered a 40 rating.[23][24][25][26][27] The network broadcast only four times a year in September, January, March and May, and had 14 films assigned to the network from the MGM library.[28]

MetroNet

In 1976, Metromedia teamed up with Ogilvy and Mather for a proposed linking of independent television stations called MetroNet. The proposed programming would consist of several family dramas on Sunday nights, a half-hour serial and a gothic series similar to Dark Shadows on weeknights, and a variety program hosted by Charo on Saturdays. The plans for MetroNet failed when advertisers balked at Metromedia's advertising rate, which was only slightly lower than that of each of the Big Three, and low national coverage, leaving for Operation Prime Time.[20]

Operation Prime Time

Operation Prime Time (OPT) was a consortium of American independent television stations to develop prime time programming for independent stations. OPT and its spin-off syndication company, Television Program Enterprises (TPE), were formed by Al Masini. During its existence, OPT was considered the de facto fourth television network.[29]

Prime Time planned three book adaptions for their shows to air in May, July and November or December 1978 with two of them being John Jakes's The Bastard and The Rebels leading the way for the rest of the book series that OPT optioned including two then currently being written. Martin Gosch's and Richard Hammer's The Last Testimony of Lucky Luciano was the third adaptation scheduled for 1978.[30]

Paramount Television Service

In 1977, Paramount Pictures made tentative plans to launch the Paramount Television Service, or Paramount Programming Service, a new fourth television network.[31] Paramount also purchased the Hughes Network, including its satellite time.[20] Set to launch in April 1978, it would have initially consisted of only one night a week of programming for three hours, with 30 Movies of the Week that would have followed Star Trek: Phase II on Saturday nights.[31][32] PTVS was delayed until the 1978–79 season due to advertisers that were cautious of purchasing commercial slots on the planned network.[33] This plan was aborted when executives decided the venture would be too costly, with no guarantee of profitability.[31] Paramount continued to produce television programs for the Big Three networks and Operation Prime Time, as well as first-run syndication.[34] Paramount would eventually create a network, UPN, in 1993.[31]

1980s

A few ad hoc networks were in developed during the 1980s as conventional full-time networks were not buying theatrical feature films as much due to declining ratings for those telecasts, with networks arguing that pay television channels and videotapes had reduced the demand for films compared to those seen in the 1960s and 1970s. The studios considered the fact that the networks usually ran their films during rating sweeps periods up against other theatrical films, as being the cause of the slide in viewership. These ad hoc networks, formed by an advertiser or studio, would provide to the production companies ratings histories that the pay services could not provide for sales in a syndicated package, and only tie up the movie for a two-week window. These were set up using a barter system, with the network retaining five minutes per hour of ad time.[mah 1] Besides the Premiere Network and Debut Network, Orion Pictures, Warner Bros. and a joint venture of Viacom and Tribune Broadcasting all followed suit in announcing the launch of their own ad hoc networks in late 1984.[35]

Golden Showcase Network

The Kraft General Foods Golden Showcase Network, or Golden Showcase Network, was launched in 1980 with assistance from SFM and ran at least to 1989.[22][36] Programs on the Golden Showcase included The Attic: The Hiding of Anne Frank and Little Girl Lost.[36]

MGM/UA Premiere Network

The Premiere Network, or MGM/UA Premiere Network, was an ad hoc network created by MGM/United Artists, which announced plans to launch in 1984, originally set for an October launch. By that summer, the network had signed affiliation agreements with eight television stations in large markets. The service was expected to broadcast 24 movies in double-runs once a month for two years. MGM received 10½ minutes of advertising time within a two-hour movie telecast, while its stations would retain 11½ minutes.[mah 2] 100 television stations were signed as affiliates by October 1984, with the planned launch pushed back and set for November 10 of that year.[37]

Debut Network

The Universal Pictures Debut Network, or simply the Debut Network, was a similar ad hoc film network created by MCA Television. The service reached agreements with ten stations in larger markets such as New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago by late 1984. The network planned to launch in two stages beginning in September 1985.[mah 3] In 1988, the movie network broadcast a special edition of Dune as a two-night event, with additional footage not included in the film's original release.[38] In June 1990, the Debut Network was ranked in fifth place among the ten highest-rated syndicated programs according to Nielsen.[39]

Premier Program Service

Premier Program Service (PPS) was born out of MCA/Universal and Paramount Communications' respective entries for ownership of TV stations. MCA had purchased WWOR-TV in New York City in 1986 (shortly before its previous owner, RKO General, began to be stripped of their broadcast properties by the FCC), while Paramount purchased a controlling interest in five independent and Fox-affiliated stations from TVX Broadcast Group in 1989 (which formed the cornerstone of the Paramount Stations Group, after it acquired the remaining interest in TVX two years later).[40] MCA Television and Paramount Domestic Television (PDT) had formed Premier Advertiser Sales, a joint venture created for advertising sales of their existing syndicated programs in September 1989, from which PPS likely took its name and served as an outgrowth.[41]

By October 1989, MCA and Paramount were shopping the planned network to potential affiliates with WWOR and Paramount's stations as the core charter outlets.[40][42] The partners were even approaching Fox-affiliated stations to affiliate with PPS, given that Premier's initial proposed schedule did not conflict with Fox's prime time schedule (which ran Saturday through Mondays at the time) and as an effort to make the network viable.[41][42] Fox was expected to lose at least one affiliate to Premier in Paramount's Philadelphia station WTXF-TV. The network was planned for a January 1, 1991 launch with two nights of programming set to air in the first year (consisting of movies on Wednesdays and series produced by the two partner companies on Fridays) and a third night (consisting of a movie block on Thursdays) before the end of the year. The two series were said to be similar to 21 Jump Street and Star Trek: The Next Generation.[42] By February 1990, Paramount Communications and MCA Inc. had disbanded their plans to launch the Premier Program Service after Fox objected to their solicitation of its affiliates to serve as its charter outlets.[43]

Harmony Premiere Network

In 1987, Harmony Gold USA collaborated with international backers, including Société Française de Productions and Reteeurope, both of the respective French, Italian and Spanish interests to set up a new project, and what the worldwide market represented to set up the Harmony Premiere Network, which was to be the next Operation Prime Time, and brings together U.S. and international financers to co-produce the products for Harmony Gold.[44]

In 1987, the company had teamed up with Italian company Silvio Berlusconi Communications to pay $150 million for a pact, to turn out 100 hours of television programming, and partnering will be dubbed by America 5 Enterprises, which will produce miniseries, TV series and telefilms using U.S. and international talent, and the two companies will share equally in costs and profits, and the company would handle worldwide and domestic television rights, with the exception of Europe, where distribution of the company will be handled through Berlusconi arm Reteitalia.[45]

In 1988, after the cancellation of Robotech II: The Sentinels, a number of the staff were recruited to work at Saban Entertainment. Carl Macek, along with his friend Jerry Beck went on to found Streamline Pictures. Meanwhile, Harmony Gold began moving away from production and began focusing more on film distribution, dot-com ventures and real estate.

Hollywood Premiere Network

After the scuttling of the plans for PPS, MCA tried again. The Hollywood Premiere Network was formed by MCA and Chris-Craft Industries, owner of several major independent stations via their United Television subsidiary. With basic cable channels snapping up movie packages, independents looked to making their own programming. Hollywood Premiere was originally tested as a two night programming block on United's KCOP and MCA's WWOR before syndicating the programming to other markets. The block took three new programs and paired them with the existing Paramount syndicated series Star Trek: The Next Generation; They Came from Outer Space and She-Wolf of London were paired in prime time Tuesday, while Shades of L.A. followed The Next Generation in prime time Wednesday.[46] The budget per episodes were estimated at $600,000 less than the network per episode cost at $1 million that the partners claimed. The Hollywood Premiere Network began broadcasting on October 9, 1990.[31] MCA and Chris-Craft canceled the package after the first season.[47] However, MCA TV was shopping the block and its shows at the NATPE January 1991 TV trade show.[48][49]

Fox Broadcasting Company

.svg.png.webp)

By 1985, there were 267 independent television stations operational in the U.S., most of which were broadcasting on UHF.[19] In May 1985, News Corporation paid $1.55 billion to acquire six independent stations in major U.S. cities from Metromedia. In October 1985, 20th Century Fox (which News Corporation founder Rupert Murdoch purchased the previous year) announced the formation of Fox Broadcasting Company, an independent television system, to compete with the three major television networks. 20th Century Fox's television division would partner with the former Metromedia stations to both produce and distribute programming. Because Metromedia was a company descended from the DuMont Television Network, radio personality Clarke Ingram argued that Fox was essentially not a new fourth network per se, but DuMont "rising from the ashes".[50] Former DuMont stations like WNYW in New York City and KTTV in Los Angeles became charter affiliates of the new network. Fox debuted on October 6, 1986, with 88 affiliates, many of them UHF stations; the network started with only a single program, The Late Show, a late-night talk show hosted by Joan Rivers, which attempted (and mightily struggled) to compete against NBC stalwart The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Fox expanded into prime time in two phases over the course of three months starting in April 1987, running two hours of programming per night on Saturdays and Sundays.

The new network was ridiculed by critics and scorned by executives of the Big Three networks. They believed that Fox, like previous fourth networks, would be limited by being on UHF stations which had poor viewership and mediocre signal reception. NBC entertainment president Brandon Tartikoff dismissively nicknamed Fox "the coat hanger network," implying that viewers would need to attach wire hangers (often used as a free alternative to set-top loop antennas used to receive UHF signals) to their television sets to view the network's shows. NBC head Grant Tinker declared, "I will never put a fourth column on my schedule board. There will only be three."[51] Indeed, just two years into its existence, the network was already struggling, and Fox executives considered pulling the plug on the network.[52] By 1990, however, Fox had cracked the top 30 in the Nielsen ratings through the surprise success of The Simpsons (an animated series spun off from The Tracey Ullman Show, one of the network's initial series), which became the first series from a fourth network to enter the top 30 since the demise of DuMont more than 30 years earlier.[53]

By then, Fox did have some advantages that DuMont did not have back in the 1950s. During its first few years, Fox programmed just under the number of hours to be legally considered a network by the FCC (by carrying only two hours of programming a few nights a week, expanding to additional nights before eventually filling all seven nights in 1993), allowing it to make money and grow in ways that the established networks were prohibited from doing. News Corporation also had more resources and money to hire and retain programming and talent than DuMont. In addition, the expansion of cable television in the 1980s and 1990s allowed more viewers to receive UHF stations clearly (along with local VHF stations), through cable systems, without having to struggle with either over-the-air antennas or television sets with limited channel tuners to receive them.[50] The Foxnet cable channel began operations in June 1991 to provide Fox's programming to smaller markets that were not served by an over-the-air Fox affiliate or one of the few superstations that carried the network. Boosted by successful shows like Married... with Children, 21 Jump Street, COPS, Beverly Hills, 90210, In Living Color, Martin, Melrose Place, Living Single and The X-Files (all appealing to the highly coveted and lucrative 18-49 demographic), Fox proved profitable by the 1990s.

In December 1993, Fox hit a major milestone when it won the rights to NFL football games from CBS,[54] a move that by all accounts firmly established itself as the fourth major television network. Soon afterward, Fox convinced several affiliates of the other networks (mostly CBS) to switch to Fox.[55]

Children's networks

- While commonly considered a part of the Fox network, the weekday Fox Children's Network (later Fox Kids Network), was launched in 1990 as a separate joint venture between Fox and some of its affiliates to compete against the Disney Afternoon syndicated block and to avoid being classified as a network under FCC rules if they aired over 15 hours of programming a week.[56]

- Bohbot Entertainment and Media moved its Bohbot Kids Network from syndication to network television on August 29, 1999, and was potentially considered to be the fourth broadcast kids' network. It consisted of two competing broadcasting services.[57][58]

Additional networks

Channel America and the Star Television Network were mainly carried on smaller full-power or low-power television stations and depended more on barter and archived public domain content rather than first-run original programming.

In the shadow of Fox's launch, Channel America was founded in 1987 as a network made up of low-power television stations; it launched in 1988 and added some cable-only affiliates.[59][60]

With the success with Fox Broadcasting Company, several other companies started to enter the fray in the 1990s to become the fifth commercial broadcast network that would allow a station to brand itself better and to stand out amongst the increasing number of channels particularly cable.[61] Chris-Craft Industries and Warner Bros. Television Distribution (syndication arm) jointly launched the Prime Time Entertainment Network in September 1993,[62][63] a consortium created in attempt at creating a new "fifth network." PTEN, Spelling Premiere Network, Family Network and the proposed WB Network & Paramount Network were being shopped in January 1994 against syndicated blocks Disney Afternoon and Universal's "Action Pack."[61] Spelling Premiere Network had launched in August 1994.[64] All American Television considered launching a first-run movie network with 22 movies as of November 1994.[65] Chris-Craft subsidiary United Television then partnered with Paramount (by then recently merged with Viacom) to create the United Paramount Network (UPN), which launched in January 1995. Meanwhile, Warner Bros. parent Time Warner formed a partnership with the Tribune Company to create The WB, which also launched less than a week after UPN made its debut.[66] Concurrently, United left PTEN's parent, the Prime Time Consortium, to focus on UPN,[67] leaving PTEN as primarily a syndicator of its remaining programs; the service shared affiliations with its respective parents' own network ventures (in some cases, resulting in PTEN's programming airing in off-peak time slots) until it finally folded in September 1997.

In March 1998, USA Broadcasting's CityVision was called a network (one of eight) by then-NBC president Bob Wright.[68] Testing was launched in June 1998 on USA's Miami station WAMI. CityVision was more of a local format that the company planned to use on additional channels.[69][70]

Paxson Communications decided to create an alternative to the six existing networks in 1998, by creating Pax TV, a network launched to provide family-oriented entertainment programs.[71] In September 1999, NBC and Pax TV became affiliated networks when NBC purchased a 32% share of Paxson Communications;[72] NBC later sold its share in the network back to Paxson in 2003.[73] Pax struggled to gain an audience, eventually dropping entertainment programming in daytime slots in favor of running infomercials; it eventually relaunched as a general entertainment network, under the name i: Independent Television, in July 2005 and became Ion Television in September 2007 (the network would gradually expand entertainment programming on its schedule over the succeeding seven years, refocusing on mainly reruns of network drama series and feature films).

In 1999, Viacom purchased CBS, effectively placing it under common ownership with UPN,[74] as a result of changes to FCC ownership rules that allowed the formation of duopolies (common ownership of two television stations within one media market). The WB, UPN and Pax all struggled throughout their existences, although they managed to gain a few hit series over their 11 years on the air (such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Star Trek: Voyager, America's Next Top Model, 7th Heaven, and Dawson's Creek). The WB and UPN, in particular, launched at a time when cable and satellite television had begun eroding viewership of even the four major networks, resulting in few WB and UPN series earning ratings registering above 5 million total viewers. Both networks also suffered from issues in recruiting affiliates, as many mid-sized and small markets had only five or fewer commercial stations, forcing either The WB, UPN, or both to settle for sharing programming time on a single station (in a few cases, being carried on an existing ABC, NBC, CBS, or Fox station); however, in some of these markets, only one or neither of the two networks was able to gain over-the-air clearance (The WB remedied this by striking a deal with Chicago affiliate WGN-TV to carry the network on its then-superstation feed at its launch,[75] before starting a group of mainly cable-only affiliates in September 1998). The WB and UPN struggled to gain new hits by 2005, and speculation constantly arose as to whether they would pull the plug.

In September 2006, UPN and The WB ended operations, and their respective parent companies (CBS Corporation and Time Warner) decide to combine their programming and management to form The CW.[76] Foxnet also ended operations at around the same time, as more Fox affiliates had signed on in smaller markets since the mid-1990s. The launch of The CW and that network's decision to make Tribune's WB stations and CBS Television Stations' UPN outlets the core of its charter affiliate group left Fox Television Stations' soon-to-be-former UPN affiliates without a network; because of this, Fox launched a secondary network, MyNetworkTV, which debuted two weeks before The CW launched.[77] Although The CW eventually found some modest footing, MyNetworkTV constantly struggled to sustain a wide audience, first with its initial telenovela format and later with its reality and film-focused lineup. Fox would convert MyNetworkTV into a programming service in September 2009, relying solely on reruns of syndicated series originally aired by other broadcast and cable networks.[78][79]

Additional networks were formed with increasing frequency immediately before and especially following the digital television transition, which gave stations the ability to multiplex their broadcast signals by adding subchannels, many of which since 2009 are being used to host networks focusing less or not at all on original content and relying mainly on programming acquired by various distributors (particularly classic series and feature films that are no longer being picked up by many cable networks).[80][81][82]

References

- Joan Crosby (February 26, 1969). "Fourth Network Hasn't Worked Yet". Raleigh Register. p. 25.

- Steve Jajkowski (2001). "Advertising on Chicago Television". Chicago Television History. Museum of Broadcast Communications. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- Timothy R. White (Spring 1992). "Hollywood on (Re)Trial: The American Broadcasting-United Paramount Merger Hearing". Cinema Journal. 31 (3): 19–36. doi:10.2307/1225506. JSTOR 1225506.

- James Schwoch (1994). "A Failed Vision: The Mutual Television Network". Velvet Light Trap. ISSN 1542-4251.

- William E. Sarmento (July 24, 1966). "Fourth TV Network Looming on Horizon". Lowell Sun. p. 20.

- Joe Cappo (September 14, 1976). "Nation's Largest Advertisers Look to Possibility of 4th TV Network". Salt Lake Tribune. p. 40.

- "New Network Will Project Rejected Film". The Oneonta Star. March 26, 1960. p. 7.

- "Network for TV-Film Shows in the Offing". The Independent. Pasadena, California. May 23, 1953. p. 4.

- Joan Crosby (February 9, 1969). "Fourth Network Hasn't Worked—Yet". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. p. 6F.

- Kerry Segrave (January 1, 1999). Movies at Home: How Hollywood Came to Television. McFarland. pp. 36, 37. ISBN 0786406542.

- "Fox Buys Into TV Network; Makes 390 Features Available". Boxoffice. November 3, 1956. p. 8.

- Dick Golembiewski (2008). Milwaukee Television History: The Analog Years. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Marquette University Press. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-87462-055-9.

- "Fourth TV Network, for Films, is Created". Boxoffice. July 7, 1956. p. 8.

- Joseph S. Iseman (2007), Joseph S. Iseman Papers, University of Maryland Libraries, hdl:1903.1/1582.

- Anthony Haden-Guest (June 11, 1984). "The Year of Sigourney Weaver". New York Magazine: 36. Retrieved October 4, 2009 – via Google Books.

- C.A. Kellner (Spring 1969). "The Rise and Fall of the Overmyer Network". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 13 (2): 125–130. doi:10.1080/08838156909386290.

- "Television: The Fourth Network". Time. Time-Life. June 29, 1962. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- Alex McNeil (1996). Total Television (4th ed.). New York City: Penguin Books. p. 3. ISBN 0-14-024916-8.

- Bernice Kanner (June 17, 1985). "Thinking About a Fourth Network". New York Magazine: 19–23. Retrieved October 4, 2009 – via Google Books.

- Gerry Nadel (May 30, 1977). "Who Owns Prime Time? The Threat of the 'Occasional' Networks". New York Magazine: 34–35. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- Tom Jory (March 21, 1983). "Stan Moger and the Ad Hoc Networks". The Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 18, 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- Kurt Brokaw (September 11, 2006). "My Days and Nights with Moger". Madison Avenue Journal. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- "Introducing The Fourth Network" (PDF). Broadcasting (Advertisement). August 27, 1973. p. 11. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- "'Yearling' slated for MGM Network" (PDF). Broadcasting: 29pdf. September 3, 1973. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- "One by One" (PDF). Broadcasting: 30. October 22, 1973. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- "Why We Created the MGM Television Network" (PDF). Broadcasting (Advertisement). March 26, 1973. p. 72. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- Dick Kleiner (July 14, 1973). "He's Making the Lion Roar Again". The Morning Record. Meridian, Connecticut. Retrieved October 3, 2012 – via Google News.

- Vernon Scott (November 10, 1973). "MGM Revival". The Ottawa Journal. Ottawa. United Press International. p. 121. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- MarketWire via Yahoo! Finance, December 1, 2010

- "Operation Prime Time sets three new shows" (PDF). Broadcasting. August 29, 1977. p. 20. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- Brian Lowry. "After 5 Years, the WB and UPN Still Head in Different Directions". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 25, 2012 – via University of Washington.

- "'Star Trek' Will Be New TV Series". The Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. June 18, 1977. p. 13. Retrieved May 25, 2012 – via Google News.

- "Snag Postpones 'Star Trek'". Boca Raton News. November 11, 1977. Retrieved May 25, 2012 – via Google News.

- "Salhany, Lucy". Museum of Broadcast Communications. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- Michele Hilmes (1999). Hollywood and Broadcasting: From Radio to Cable. University of Illinois Press. p. 191. ISBN 0252068467. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- Key, Janet (November 1, 1989). "Despite Mega-budget, Att Sees Real Bargain In 'The Final Days'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

..."Kraft General Foods' "Golden Showcase" dramas...

- Stephen Farber (October 23, 1984). "Film Studio's New Approach to TV". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- Erica Davison; Annette Sheen (2004). The Cinema of David Lynch: American Dreams, Nightmare Visions. Wallflower Press. p. 207. ISBN 190336485X. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- "BY THE NUMBERS : The Top 10 Syndicated Television Shows". Los Angeles Times. June 25, 1990. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Jennifer Holt (2011). Empires of Entertainment: Media Industries and the Politics of Deregulation, 1980-1996. Rutgers University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0813550527. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Richard W. Stevenson (October 20, 1989). "Plan Seen For Another TV Network". The New York Times. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Nancy Rivera Brooks (October 20, 1989). "Paramount, MCA May Start a 5th Television Network". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Michael Cieply (February 22, 1990). "Disney, Fox Clash Over Children's TV Programming". Los Angeles Times. p. 2. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Gelman, Morrie (April 1, 1987). "Harmony Gold TV Unveils Intl. Coproduction Project". Variety. pp. 50, 70.

- "Harmony Gold And Italy's Berlusconi In $150-Mil Pact". Variety. June 10, 1987. pp. 42, 69.

- Cerone, Daniel (October 7, 1990). "Ready for Prime Time? : With Three New Nighttime Shows, Independent KCOP Tries To Take On The Networks". Los Angeles Times.

- "MCA TV Spins The Bottle". Variety. April 10, 1995. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- "Aisles of Programing at NATPE: MCA TV" (PDF). Broadcasting: 95. January 14, 1991. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Guider, Elizabeth (January 14, 1991). "TV Reps Cast A Wary Eye Over NATPE". Variety. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Clarke Ingram. "Channel Nine: Others". DuMont Television Network Historical Web Site.

- Dan Kimmel (2004). "Chapter 1". The Fourth Network. Chicago, Illinois: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-572-1. Retrieved October 4, 2009 – via WNYC.

- Ed Siegel (July 5, 1988). "Fourth Network Fights for Survival". Boston Globe. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- Highest-rated series is based on the annual top-rated programs list compiled by Nielsen Media Research and reported in: Tim Marsh & Earle Brooks (2007). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network TV Shows (9th ed.). New York City: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-345-49773-4.

- "CBS, NBC Battle for AFC Rights // Fox Steals NFC Package". Chicago Sun-Times. Sun-Times Media Group. December 18, 1993. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- "Fox Gains 12 Stations in New World Deal". Chicago Sun-Times. Sun-Times Media Group. May 23, 1994. Archived from the original on October 11, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- Michael Cieply (February 22, 1990). "Disney, Fox Clash Over Children's TV Programming". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- "It's Show Time! The Fall TV Preview". Animation World Magazine. Vol. 4, no. 6. Animation World Network. September 1999. p. 2. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- Schlosser, Joe (October 5, 1998). "Bohbot zigs out of syndication". Broadcasting & Cable. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- Eric Schatz (July 2, 1990). "Channel America Woos Ops, Advertisers". Multichannel News. Fairchild Publications. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- M. Bosko (July 1995). "On Ramp: Opportunities on Satellite". Videomaker. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- Cerone, Daniel (January 16, 1994). "TELEVISION : There's Action Off the Beaten Path : The ground is shifting in TV's prime time as a slew of new shows arrive--but don't go looking for them in the usual places". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- Susan King (January 23, 1994). "Space, 2258, in the Year 1994". Los Angeles Times. p. 4. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- Jim Benson (May 28, 1993). "Warner weblet to 2-night sked". Variety.

- Kleid, Beth (August 28, 1994). "Focus : Spelling Check : Mega-Producer's Latest Venture is His Own 'Network'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- "All American Television. (planning movie network)". Broadcasting & Cable. November 21, 1994. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- David Tobenkin (January 2, 1995). "New Players Get Ready to Roll: UPN, WB Network Prepare to Take Their Shots". Broadcasting & Cable. Cathers Business Information. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- "BHC Communications, Inc. Companies History". Company Histories. Funding Universe. 1997. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- Albiniak, Paige (March 2, 1998). "Wright charts course through sea of nets" (PDF). Broadcasting & Cable. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- Fabrikant, Geraldine (November 23, 1998). "Diller's Latest Tele-Vision; First, a Network of Cubic Zirconium. Now, a Station of Lips and Hardbodies". The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- Littleton, Cynthia (January 18, 1999). "CityVision may export local format". Variety. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- Lisa de Moraes (August 29, 1998). "On Monday, the Genesis of PAX TV". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- Bill Carter (September 17, 1999). "NBC Completes Acquisition Of 32% Stake in Paxson". The Media Business. The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- Bill Carter (November 14, 2003). "Advertising; NBC Moves to Break Up Relationship with Paxson". The Media Business. The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- "Viacom Inc. History". Company Profiles. Funding Universe. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- "Time Warner Takes Crucial Step Toward New Network Television: A pact with superstation WGN-TV gives it access to 73% of homes. Analysts say that will still leave gaps". Los Angeles Times. December 4, 1993. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- Meg James (January 25, 2006). "CBS, Warner to Shut Down 2 Networks and Form Hybrid". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "News Corp. to Launch New Mini-Network for UPN Stations". USA Today. Gannett Company. February 22, 2006. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- Michael Malone (February 9, 2009). "MyNetworkTV Shifts From Network to Programming Service". Broadcasting & Cable. NewBay Media. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- "MyNetworkTV Changing Business Model". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. February 9, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- Allison Romano (March 9, 2008). "Local Stations Multiply". Broadcasting & Cable. Reed Business Information. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Cynthia Littleton (June 18, 2014). "Wily Indies Succeed on Digital Channels Where Majors Struggle". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- Stephen Battaglio (April 1, 2015). "Classic TV shows get new life on digital airwaves". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- Kerry Segrave (January 1, 1999). Movies at Home: How Hollywood Came to Television. McFarland. pp. 145–146. ISBN 9780786406548. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- Kerry Segrave (January 1, 1999). Movies at Home: How Hollywood Came to Television. McFarland. p. 146. ISBN 9780786406548. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- Kerry Segrave (January 1, 1999). Movies at Home: How Hollywood Came to Television. McFarland. p. 147. ISBN 9780786406548. Retrieved April 8, 2015.