Hygiene

Hygiene is a set of practices performed to preserve health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases."[2] Personal hygiene refers to maintaining the body's cleanliness. Hygiene activities can be grouped into the following: home and everyday hygiene, personal hygiene, medical hygiene, sleep hygiene, and food hygiene. Home and every day hygiene includes hand washing, respiratory hygiene, food hygiene at home, hygiene in the kitchen, hygiene in the bathroom, laundry hygiene, and medical hygiene at home.

Many people equate hygiene with "cleanliness", but hygiene is a broad term. It includes such personal habit choices as how frequently to take a shower or bath, wash hands, trim fingernails, and wash clothes. It also includes attention to keeping surfaces in the home and workplace clean, including bathroom facilities. Adherence to regular hygiene practices is often regarded as a socially responsible and respectable behavior, while neglecting proper hygiene can be perceived as unclean or unsanitary, and may be considered socially unacceptable or disrespectful, while also posing a risk to public health.

Definition and overview

Hygiene is a practice[3] related to lifestyle, cleanliness, health, and medicine. In medicine and everyday life, hygiene practices are preventive measures that reduce the incidence and spread of germs leading to disease.

Hygiene practices vary from one culture to another.[4]

In the manufacturing of food,[5] pharmaceuticals,[6] cosmetics,[7] and other products, good hygiene is a critical component of quality assurance.

The terms cleanliness and hygiene are often used interchangeably, which can cause confusion. In general, hygiene refers to practices that prevent spread of disease-causing organisms. Cleaning processes (e.g., handwashing[1]) remove infectious microbes as well as dirt and soil, and are thus often the means to achieve hygiene.

Other uses of the term are as follows: body hygiene, personal hygiene, sleep hygiene, mental hygiene, dental hygiene, and occupational hygiene, used in connection with public health.

Home and everyday hygiene

Home hygiene overview

Home hygiene pertains to the hygiene practices that prevent or minimize the spread of disease at home and other everyday settings such as social settings, public transport, the workplace, public places, and more. Hygiene in a variety of settings plays an important role in preventing the spread of infectious diseases.[8] It includes procedures like hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, food and water hygiene, general home hygiene (hygiene of environmental sites and surfaces), care of domestic animals, and home health care (the care of those who are at greater risk of infection).

At present, these components of hygiene tend to be regarded as separate issues, although based on the same underlying microbiological principles. Preventing the spread of diseases means breaking the chain of infection transmission so that infection cannot spread. "Targeted hygiene" is based on identifying the routes of pathogen spread in the home and introducing hygiene practices at critical times to break the chain of infection.[9] It uses a risk-based approach based on Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP).

The main sources of infection in the home are people (who are carriers or are infected), foods (particularly raw foods), water, pets, and domestic animals.[10] Sites that accumulate stagnant water – such as sinks, toilets, waste pipes, cleaning tools, and face cloths – readily support microbial growth and can become secondary reservoirs of infection, though species are mostly those that threaten "at risk" groups. Pathogens (such as potentially infectious bacteria and viruses – colloquially called "germs") are constantly shed via mucous membranes, feces, vomit, skin scales, and other means. When circumstances combine, people are exposed, either directly or via food or water, and can develop an infection.

The main "highways" for the spread of pathogens in the home are the hands, hand and food contact surfaces, and cleaning cloths and utensils (e.g. fecal–oral route of transmission). Pathogens can also be spread via clothing and household linens, such as towels. Utilities such as toilets and wash basins were invented to deal safely with human waste but still have risks associated with them. Safe disposal of human waste is a fundamental need; poor sanitation is a primary cause of diarrhea disease in low-income communities. Respiratory viruses and fungal spores spread via the air.

Good home hygiene means engaging in hygiene practices at critical points to break the chain of infection.[9][10] Because the "infectious dose" for some pathogens can be very small (10–100 viable units or even less for some viruses), and infection can result from direct transfer of pathogens from surfaces via hands or food to the mouth, nasal mucous, or the eye, "hygienic cleaning" procedures should be adopted to eliminate pathogens from critical surfaces.

Hand washing

Hand washing (or handwashing), also known as hand hygiene, is the act of cleaning one's hands with soap or handwash and water to remove viruses/bacteria/microorganisms, dirt, grease, or other harmful and unwanted substances stuck to the hands. Drying of the washed hands is part of the process as wet and moist hands are more easily recontaminated.[11][12] If soap and water are unavailable, hand sanitizer that is at least 60% (v/v) alcohol in water can be used as long as hands are not visibly excessively dirty or greasy.[13][14] Hand hygiene is central to preventing the spread of infectious diseases in home and everyday life settings.[15]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends washing hands for at least 20 seconds before and after certain activities.[16][17] These include the five critical times during the day where washing hands with soap is important to reduce fecal-oral transmission of disease: after using the toilet (for urination, defecation, menstrual hygiene), after cleaning a child's bottom (changing diapers), before feeding a child, before eating and before/after preparing food or handling raw meat, fish, or poultry.[18].jpg.webp)

Respiratory hygiene

Correct respiratory and hand hygiene when coughing and sneezing reduces the spread of pathogens particularly during the cold and flu season:[8]

- Carry tissues and use them to catch coughs and sneezes, or sneeze into your elbow.

- Dispose of tissues as soon as possible.

Hygiene in the kitchen, bathroom and toilet

Routine cleaning of hands, food, sites, and surfaces (such as toilet seats and flush handles, door and tap handles, work surfaces, and bath and basin surfaces) in the kitchen, bathroom, and toilet rooms reduces the spread of pathogens.[19] The infection risk from flush toilets is not high, provided they are properly maintained, although some splashing and aerosol formation can occur during flushing, particularly when someone has diarrhea. Pathogens can survive in the scum or scale left behind on baths, showers, and washbasins after washing and bathing.

Thorough cleaning is important to prevent the spread of fungal infections. Molds can live on wall and floor tiles and on shower curtains. Mold can be responsible for infections, cause allergic reactions, deteriorate/damage surfaces, and cause unpleasant odors. Primary sites of fungal growth are inanimate surfaces, including carpets and soft furnishings.[20] Airborne fungi are usually associated with damp conditions, poor ventilation, or closed air systems.

Hygienic cleaning can be done through:

- Mechanical removal (i.e., cleaning) using a soap or detergent. To be effective as a hygiene measure, this process must be followed by thorough rinsing under running water to remove pathogens from the surface.

- Using a process or product that inactivates the pathogens in situ. Pathogen kill is achieved using a "micro-biocidal" product, i.e., a disinfectant or antibacterial product; waterless hand sanitizer; or by application of heat.

- In some cases combined pathogen removal with kill is used, e.g., laundering of clothing and household linens such as towels and bed linen.

Laundry hygiene

Laundry hygiene involves practices that prevent disease and its spread via soiled clothing and household linens such as towels.[21] Items most likely to be contaminated with pathogens are those that come into direct contact with the body, e.g., underwear, personal towels, facecloths, nappies. Cloths or other fabric items used during food preparation, or for cleaning the toilet or cleaning up material such as feces or vomit are a particular risk.[10]

Microbiological and epidemiological data indicates that clothing and household linens are a risk factor for infection transmission in home and everyday life settings as well as institutional settings. The lack of quantitative data linking contaminated clothing to infection in the domestic setting makes it difficult to assess the extent of this risk.[21][10][22] This also indicates that risks from clothing and household linens are somewhat less than those associated with hands, hand contact and food contact surfaces, and cleaning cloths, but even so these risks need to be managed through effective laundering practices. In the home, this should be carried out as part of a multibarrier approach to hygiene which includes hand, food, respiratory, and other hygiene practices.[21][10][22]

Infectious disease risks from contaminated clothing can increase significantly under certain conditions, e.g., in healthcare situations in hospitals, care homes, and the domestic setting where someone has diarrhoea, vomiting, or a skin or wound infection. The risk increases in circumstances where someone has reduced immunity to infection.

Hygiene measures, including laundry hygiene, are an important part of reducing spread of antibiotic-resistant strains of infectious organisms.[23][24][25] In the community, otherwise-healthy people can become persistent skin carriers of MRSA, or faecal carriers of enterobacteria strains which can carry multi-antibiotic resistance factors (e.g. NDM-1 or ESBL-producing strains). The risks are not apparent until, for example, they are admitted to hospital, when they can become "self infected" with their own resistant organisms following a surgical procedure. As persistent nasal, skin, or bowel carriage in the healthy population spreads "silently" across the world, the risks from resistant strains in both hospitals and the community increases.[24] In particular the data indicates that clothing and household linens are a risk factor for spread of S. aureus (including MRSA and PVL-producing MRSA strains), and that effectiveness of laundry processes may be an important factor in defining the rate of community spread of these strains.[21][26] Experience in the United States suggests that these strains are transmissible within families and in community settings such as prisons, schools, and sport teams. Skin-to-skin contact (including unabraded skin) and indirect contact with contaminated objects such as towels, sheets, and sports equipment seem to represent the mode of transmission.[21]

During laundering, temperature and detergent work to reduce microbial contamination levels on fabrics. Soil and microbes from fabrics are severed and suspended in the wash water. These are then "washed away" during the rinse and spin cycles. In addition to physical removal, micro-organisms can be killed by thermal inactivation which increases as the temperature is increased. Chemical inactivation of microbes by the surfactants and activated oxygen-based bleach used in detergents contributes to the hygiene effectiveness of laundering. Adding hypochlorite bleach in the washing process achieves inactivation of microbes. A number of other factors can contribute including drying and ironing.

Drying laundry on a line in direct sunlight is known to reduce pathogens.[27]

In 2013 the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene reviewed 30 studies of the hygiene effectiveness of laundering at temperatures ranging from room temperature to 70 °C (158 °F), under varying conditions.[28] A key finding was the lack of standardization and control within studies, and the variability in test conditions between studies such as wash cycle time, number of rinses, and other factors. The consequent variability in the data (i.e., the reduction in contamination on fabrics) in turn makes it extremely difficult to propose guidelines for laundering with any confidence. As a result, there is significant variability in the recommendations for hygienic laundering given by different agencies.[29]

Medical hygiene at home

Medical hygiene pertains to hygiene practices that prevent or minimize disease and the spreading of disease in relation to administering medical care to those who are infected or who are more at risk of infection in the home. Members of "at-risk" groups are cared for at home by a carer who may be a household member and who requires a good knowledge of hygiene. People with reduced immunity to infection, who are looked after at home, make up an increasing proportion of the population (as of 2009, up to 20%).[8] The largest proportion are the elderly who have co-morbidities that reduce their immunity to infection. It also includes the very young, patients discharged from hospital, taking immuno-suppressive drugs, or using invasive systems, etc. For patients discharged from hospital, or being treated at home, special "medical hygiene" procedures may need to be performed for them, such as catheter or dressing replacement, which puts them at higher risk of infection.

Antiseptics may be applied to cuts, wounds, and abrasions of the skin to prevent the entry of harmful bacteria that can cause sepsis. Day-to-day hygiene practices, other than special medical hygiene procedures,[30] are no different for those at increased risk of infection than for other family members. The difference is that, if hygiene practices are not correctly carried out, the risk of infection is much greater.

Disinfectants and antibacterials in home hygiene

Chemical disinfectants[31] are products that kill pathogens. If the product is a disinfectant, the label on the product should say "disinfectant" or "kills" pathogens. Some commercial products, e.g. bleaches, even though they are technically disinfectants, say that they "kill pathogens" but are not actually labelled as "disinfectants". Not all disinfectants kill all types of pathogens. All disinfectants kill bacteria (called bactericidal). Some also kill fungi (fungicidal), bacterial spores (sporicidal), or viruses (virucidal).

An antibacterial product acts against bacteria in some unspecified way. Some products labelled "antibacterial" kill bacteria while others may contain a concentration of active ingredient that only prevents them from multiplying. It is, therefore, important to check whether the product label states that it "kills bacteria". An antibacterial is not necessarily anti-fungal or anti-viral unless this is stated on the label.

The term sanitizer has been used to define substances that both clean and disinfect. More recently this term has been applied to alcohol-based products that disinfect the hands (alcohol hand sanitizers). Alcohol hand sanitizers however are not considered to be effective on soiled hands.[32]

The term biocide is a broad term for a substance that kills, inactivates or otherwise controls living organisms. It includes antiseptics and disinfectants, which combat micro-organisms, and pesticides.

Personal hygiene

Regular activities

Personal hygiene involves those practices performed by a person to care for their bodily health and well-being through cleanliness. Motivations for personal hygiene practice include reduction of personal illness, healing from illness, optimal health and sense of wellbeing, social acceptance, and prevention of spread of illness to others. What is considered proper personal hygiene can be culture-specific and may change over time.

Practices that are generally considered proper hygiene include showering or bathing regularly, washing hands regularly and especially before handling food, washing scalp hair, keeping hair short or removing hair, wearing clean clothing, brushing teeth, and trimming fingernails and toenails. Some practices are gender-specific, such as by a woman during her menstruation.

Toiletry bags hold body hygiene and toiletry supplies.

Anal hygiene is the practice that a person performs on their anal area after defecation. The anus and buttocks may be either washed with liquids or wiped with toilet paper, or by adding gel wipe to toilet tissue as an alternative to wet wipes or other solid materials in order to remove remnants of feces.

People tend to develop a routine for attending to their personal hygiene needs. Other personal hygienic practices include covering one's mouth when coughing, disposal of soiled tissues appropriately, making sure toilets are clean, and making sure food handling areas are clean, besides other practices. Some cultures do not kiss or shake hands in order to reduce transmission of bacteria by contact.

Personal grooming extends personal hygiene as it pertains to the maintenance of a good personal and public appearance, which need not necessarily be hygienic. It may involve, for example, using deodorants or perfume, shaving, or combing.

Hygiene of internal ear canals

Excessive cleaning of the ear canals can result in infection or irritation. The ear canals require less care than other parts of the body because they are sensitive and mostly self-cleaning. There is a slow and orderly migration of the skin lining the ear canal from the eardrum to the outer opening of the ear. Old earwax is constantly being transported from the deeper areas of the ear canal out to the opening where it usually dries, flakes, and falls out.[33] Attempts to clean the ear canals through the removal of earwax can push debris and foreign material into the ear that the natural movement of ear wax out of the ear would have removed.

Oral hygiene

It is recommended that all healthy adults brush twice a day,[34][35] softly,[36] with the correct technique, replacing their toothbrush every few months (~3).[37]

There are a number of common oral hygiene misconceptions. The National Health Service (NHS) of England recommends not rinsing the mouth with water after brushing – only to spit out excess toothpaste. They claim that this helps fluoride from toothpaste bond to teeth for its preventative effects against tooth decay.[38] It is also not recommended to brush immediately after drinking acidic substances, including sparkling water.[39] It is also recommended to floss once a day,[40] with a different piece of floss at each flossing session. The effectiveness of amorphous calcium phosphate products, such as Tooth Mousse, is in debate.[41] Visits to a dentist for a checkup every year at least are recommended.[42]

Sleep hygiene

Sleep hygiene is the recommended behavioral and environmental practices that promote better quality sleep.[43] These recommendations were developed in the late 1970s as a method to help people with mild to moderate insomnia, but, as of 2014, the evidence for effectiveness of individual recommendations is "limited and inconclusive".[43] Clinicians assess the sleep hygiene of people who present with insomnia and other conditions, such as depression, and offer recommendations based on the assessment. Sleep hygiene recommendations include establishing a regular sleep schedule, using naps with care, not exercising physically or mentally too close to bedtime, and avoiding alcohol as well as nicotine, caffeine, and other stimulants in the hours before bedtime.[44] Further recommendations include limiting worry, limiting exposure to light in the hours before sleep, getting out of bed if sleep does not come, not using the bed for anything but sleep, and having a peaceful, comfortable, and dark sleep environment.

Personal care services hygiene

Personal care services hygiene pertains to the care and use of instruments used in the administration of personal care services to people:

Personal care hygiene practices include:

- sterilization of instruments used by service providers including hairdressers, aestheticians, and other service providers

- sterilization by autoclave of instruments used in body piercing and tattooing

- cleaning hands

Challenges

Excessive body hygiene is a possible sign of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Neglecting bodily hygiene, or the cleanliness of one's environment, may be a sign of major depression and other psychological disorders.

Hygiene hypothesis and allergies

Although media coverage of the hygiene hypothesis has declined, popular folklore continues to sometimes assert that dirt is healthy and hygiene unnatural. This has caused health professionals to be concerned that hygiene behaviors which are the foundation of public health are being undermined. In response to the need for effective hygiene in home and everyday life settings, the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene developed a "risk-based" or targeted approach to home hygiene that seeks to ensure that hygiene measures are focused on the places and times most critical for infection transmission.[9] While targeted hygiene was originally developed as an effective approach to hygiene practice, it also seeks, as far as possible, to sustain "normal" levels of exposure to the microbial flora of our environment to the extent that is important to build a balanced immune system.

Although there is substantial evidence that some microbial exposures in early childhood can in some way protect against allergies, there is no evidence that humans need exposure to harmful microbes (infection) or that it is necessary to develop a clinical infection.[45] Nor is there evidence that hygiene measures such as hand washing, food hygiene, etc., are linked to increased susceptibility to atopic disease. If this is the case, there is no conflict between the goals of preventing infection and minimizing allergies. A consensus is now developing among experts that the answer lies in more fundamental changes in lifestyles that have led to decreased exposure to certain microbial or other species, such as helminths, that are important for development of immuno-regulatory mechanisms.[46] There is still much uncertainty as to which lifestyle factors are involved.

Medical hygiene

Medical hygiene pertains to hygiene practices related to the administration of medicine and medical care that prevents or minimizes the spread of disease.

Medical hygiene practices include:

- isolation of infectious persons or materials to prevent spread of infection

- sterilization of instruments used in surgical procedures

- proper bandaging and dressing of injuries

- safe disposal of medical waste

- disinfection of reusables (i.e., linen, pads, uniforms)

- scrubbing up, handwashing, especially in an operating room, but in more general health-care settings as well, where diseases can be transmitted

- ethanol-based sanitizers

Most of these practices were developed in the 19th century and were well-established by the mid-20th century. Some procedures (such as disposal of medical waste) were refined in response to late-20th century disease outbreaks, notably AIDS and Ebola.

Food hygiene

Culinary hygiene (or food hygiene) pertains to practices of food management and cooking that prevent food contamination, prevent food poisoning, and minimize the transmission of disease to other foods, humans, or animals. Culinary hygiene practices specify safe ways to handle, store, prepare, serve, and eat food.

Hygiene aspects in low- and middle-income countries

In developing countries (or low- and middle-income countries), universal access to water and sanitation, coupled with hygiene promotion, is essential in reducing infectious diseases. This approach has been integrated into the Sustainable Development Goal Number 6 whose second target states: "By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations".[50] Due to their close linkages, water, sanitation, hygiene are together abbreviated and funded under the term WASH in development cooperation.

About two million people die every year due to diarrheal diseases; most of them are children less than five years of age.[51] The most affected are people in developing countries who live in extreme conditions of poverty, normally peri-urban dwellers or rural inhabitants. Providing access to sufficient quantities of safe water and facilities for a sanitary disposal of excreta, and introducing sound hygiene behaviors are important in order to reduce the burden of disease.

Research shows that, if widely practiced, hand washing with soap could reduce diarrhea by almost fifty percent[52] and respiratory infections by nearly twenty-five percent[53] Hand washing with soap also reduces the incidence of skin diseases,[54] and eye infections like trachoma and intestinal worms, especially ascariasis and trichuriasis.[55] Other hygiene practices, such as safe disposal of waste, surface hygiene, and care of domestic animals, are important in low income communities to break the chain of infection transmission.[56]

Cleaning of toilets and hand wash facilities is important to prevent odors and make them socially acceptable. Social acceptance is an important part of encouraging people to use toilets and wash their hands, in situations where open defecation is still seen as a possible alternative, e.g. in rural areas of some developing countries.

Household water treatment and safe storage

Household water treatment and safe storage ensure drinking water is safe for consumption. These interventions are part of the approach of self-supply of water for households.[57] Drinking water quality remains a significant problem in developing[58] and in developed countries;[59] even in the European region it is estimated that 120 million people do not have access to safe drinking water. Point-of-use water quality interventions can reduce diarrheal disease in communities where water quality is poor or in emergency situations where there is a breakdown in water supply.[58][59][60][61] Since water can become contaminated during storage at home (e.g. by contact with contaminated hands or using dirty storage vessels), safe storage of water in the home is important.

Methods for treatment of drinking water at the household level include:[19][61]

- chemical disinfection using chlorine or iodine

- boiling

- filtration using ceramic filters

- solar disinfection — Solar disinfection is an effective method, especially when no chemical disinfectants are available.[62]

- UV irradiation — Community or household UV systems may be batch or flow-though. The lamps can be suspended above the water channel or submerged in the water flow.

- combined flocculation/disinfection systems — available as sachets of powder that act by coagulating and flocculating sediments in water followed by release of chlorine

- multibarrier methods — Some systems use two or more of the above treatments in combination or in succession to optimize efficacy.

- portable water purification devices

History

China

Bathing culture in Chinese literature can be traced back to the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BCE), when Oracle bone inscriptions describe people washing their hair and body in a bath. The Book of Rites, a work regarding Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE) ritual, politics, and culture compiled during the Warring States period, recommends that people take a hot shower every five days, and wash their hair every three days. It was also considered good manners to take a bath provided by the host before a dinner. In the Han dynasty, bathing became a regular activity, and for government officials bathing was required every five days.[63]

Ancient bath facilities have been found in ancient Chinese cities, such as Dongzhouyang archaeological site in Henan Province. Bathrooms were called Bi (Chinese: 湢), and bathtubs were made of bronze or timber.[64] Bath beans – a powdery soap mixture of ground beans, cloves, eaglewood, flowers, and even powdered jade – were recorded in the Han Dynasty. Bath beans were considered luxury toiletries, while common people simply used powdered beans without spices mixed in. Luxurious bathhouses built around hot springs were recorded in Tang dynasty.[63] While royal bathhouses and bathrooms were common among ancient Chinese nobles and commoners, public bathhouses were a relatively late development. In the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), public bathhouses became popular and people could find them readily.[64] Bathing became an essential part of social life and recreation. Bathhouses often provided massage, nail cutting service, rubdown service, ear cleaning, food, and beverages.[64] Marco Polo, who traveled to China during the Yuan dynasty, noted Chinese bathhouses were using coal to heat the bathhouse, which he had never seen before in Europe.[65] Coal was so plentiful that Chinese people of every social class had bathrooms in their houses, and people took showers every day in the winter for enjoyment.[66]

A typical Ming dynasty bathhouse had slabbed floors and brick domed ceilings. A huge boiler would be installed in the back of the house, connected with the bathing pool through a tunnel. Water could be pumped into the pool by turning wheels attended by the staff.[64]

Japan

The origin of Japanese bathing is misogi, ritual purification with water.[67]

In the Heian period (794–1185 CE), houses of prominent families, such as the families of court nobles or samurai, had baths. The bath had lost its religious significance and instead became leisure. Misogi became gyōzui (to bathe in a shallow wooden tub).[67]: 36 In the 17th century, the first European visitors to Japan recorded the habit of daily baths in mixed sex groups.[67]

Indian subcontinent

The earliest written account of elaborate codes of hygiene can be found in several Hindu texts, such as the Manusmriti and the Vishnu Purana.[68] Bathing is one of the five nitya karmas (daily duties) in Hinduism, and not performing it leads to sin, according to some scriptures.

Ayurveda is a system of medicine developed in ancient times that is still practiced in India, mostly combined with conventional Western medicine. Contemporary Ayurveda stresses a sattvic diet and good digestion and excretion. Hygiene measures include oil pulling, and tongue scraping. Detoxification also plays an important role.[69]

Mesoamerica

.jpg.webp)

Spanish chronicles describe the bathing habits of the peoples of Mesoamerica during and after the conquest. Bernal Díaz del Castillo describes Moctezuma (the Mexica, or Aztec, emperor at the arrival of Cortés) in his Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España as being "...Very neat and cleanly, bathing every day each afternoon...".

Bathing was not restricted to the elite, but was practised by all people; the chronicler Tomás López Medel wrote after a journey to Central America that "Bathing and the custom of washing oneself is so quotidian [common] amongst the Indians, both of cold and hot lands, as is eating, and this is done in fountains and rivers and other water to which they have access, without anything other than pure water..."[70]

The Mesoamerican bath, known as temazcal in Spanish, from the Nahuatl word temazcalli, a compound of temaz ("steam") and calli ("house"), consists of a room, often in the form of a small dome, with an exterior firebox known as texictle (teʃict͜ɬe) that heats a small portion of the room's wall made of volcanic rocks; after this wall has been heated, water is poured on it to produce steam, an action known as tlasas. As the steam accumulates in the upper part of the room a person in charge uses a bough to direct the steam to the bathers who are lying on the ground, with which he later gives them a massage, then the bathers scrub themselves with a small flat river stone and finally the person in charge introduces buckets with water along with soap and grass used to rinse. This bath had also ritual importance, and was tied to the goddess Toci; it is also therapeutic when medicinal herbs are used in the water for the tlasas. It is still used in Mexico.[70]

Europe

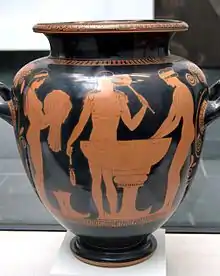

Regular bathing was a hallmark of Roman civilization.[71] Elaborate baths were constructed in urban areas to serve the public, who typically demanded the infrastructure to maintain personal cleanliness. The complexes usually consisted of large, swimming pool-like baths, smaller cold and hot pools, saunas, and spa-like facilities where people could be depilated, oiled, and massaged. Water was constantly changed by an aqueduct-fed flow. Bathing outside of urban centers involved smaller, less elaborate bathing facilities, or simply the use of clean bodies of water. Roman cities also had large sewers, such as Rome's Cloaca Maxima, into which public and private latrines drained. Romans did not have demand-flush toilets but did have some toilets with a continuous flow of water under them. The Romans used scented oils (mostly from Egypt), among other alternatives.

Christianity places an emphasis on hygiene.[72] Despite the denunciation of the mixed bathing style of Roman pools by early Christian clergy, as well as of the pagan custom of women bathing naked in front of men, this did not stop the Church from urging its followers to go to public baths for bathing,[72] which contributed to hygiene and good health according to the Church Fathers Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian.[73][74] The Church built public bathing facilities that were separated by sex near monasteries and pilgrimage sites. The popes situated baths within church basilicas and monasteries starting in the early Middle Ages.[73] Pope Gregory the Great promoted bathing as a bodily need.[74] The use of water in many Christian countries is due in part to the Biblical toilet etiquette which encourages washing after all instances of defecation.[75] Bidet and bidet showers were used in regions where water was considered essential for anal cleansing.[75][76]

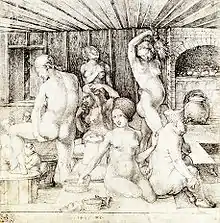

Contrary to popular belief,[77] and although some of the Early Christian leaders, such as Boniface I,[78] condemned bathing as unspiritual,[79] bathing and sanitation were not lost in Europe with the collapse of the Roman Empire.[80][81] Public bathhouses were common in medieval Christendom larger towns and cities such as Constantinople, Paris, Regensburg, Rome and Naples.[82] Great bathhouses were built in Byzantine centers such as Constantinople and Antioch.[83]

Northern Europeans were not in the habit of bathing: in the ninth century, Notker the Stammerer, a Frankish monk of St. Gall, related a disapproving anecdote that attributed ill results of personal hygiene to an Italian fashion:

There was a certain deacon who followed the habits of the Italians in that he was perpetually trying to resist nature. He used to take baths, he had his head very closely shaved, he polished his skin, he cleaned his nail, he had his hair cut as short as if it were turned on a lathe, and he wore linen underclothes and a snow-white shirt.

Secular medieval texts refer to the washing of hands before and after meals, but Sone de Nansay, a hero of a 13th-century romance, discovers to his chagrin that the Norwegians do not wash up after eating.[84] In the 11th and 12th centuries, bathing was essential to the Western European upper class: the Cluniac monasteries to which they resorted or retired were always provided with bathhouses, and even the monks were required to take full immersion baths twice a year, at the two Christian festivals of renewal, though exhorted not to uncover themselves from under their bathing sheets.[85] In the 14th century Tuscany, the newlywed couple's bath together was such a firm convention one such couple, in a large coopered tub, is illustrated in fresco in the town hall of San Gimignano.[86] Catholic religious orders of the Augustinians' and Benedictines' rules contained ritual purification,[87] and, inspired by Benedict of Nursia, encouragement for the practice of therapeutic bathing; Benedictine monks played a role in the development and promotion of spas.[88]

Bathing fell out of fashion in Northern Europe long before the Renaissance, when the communal public baths of German cities were a wonder to Italian visitors. Bathing was replaced by the heavy use of sweat-bathing and perfume, as it was thought in Europe that water could carry disease into the body through the skin. Bathing encouraged an erotic atmosphere that was played upon by the writers of romances intended for the upper class;[84] in the tale of Melusine the bath was a crucial element of the plot. "Bathing and grooming were regarded with suspicion by moralists, however, because they unveiled the attractiveness of the body. Bathing was said to be a prelude to sin, and in the penitential of Burchard of Worms we find a full catalogue of the sins that ensued when men and women bathed together."[85] Medieval church authorities believed that public bathing created an environment open to immorality and disease; the 26 public baths of Paris in the late 13th century were strictly overseen by the civil authorities.[85] At a later date Roman Catholic Church officials even banned public bathing in an unsuccessful effort to halt syphilis epidemics from sweeping Europe.[89] Protestantism also played a prominent role in the development of the British spas.[88]

Until the late 19th century, only the elite in Western cities typically possessed indoor facilities for relieving bodily functions. The poorer majority used communal facilities built above cesspools in backyards and courtyards. This changed after Dr. John Snow discovered that cholera was transmitted by the fecal contamination of water. Though it took decades for his findings to gain wide acceptance, governments and sanitary reformers were eventually convinced of the health benefits of using sewers to keep human waste from contaminating the water. This encouraged the widespread adoption of both the flush toilet and the moral imperative that bathrooms should be indoors and as private as possible.[90]

Modern sanitation was not widely adopted until the 19th and 20th centuries. According to medieval historian Lynn Thorndike, people in Medieval Europe probably bathed more than people did in the 19th century.[91] Some time after Louis Pasteur's experiments proved the germ theory of disease and Joseph Lister and others put this into practice in sanitation, hygienic practices came to be regarded as synonymous with health, as they are in modern times.

The importance of hand washing for human health – particularly for people in vulnerable circumstances like mothers who had just given birth or wounded soldiers in hospitals – was first recognized in the mid 19th century by two pioneers of hand hygiene: the Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis who worked in Vienna, Austria, and Florence Nightingale, the English "founder of modern nursing".[92] At that time most people still believed that infections were caused by foul odors called miasmas.

Middle East

Islam stresses the importance of cleanliness and personal hygiene.[93] Islamic hygienical jurisprudence, which dates back to the 7th century, has a number of elaborate rules. Taharah (ritual purity) involves performing wudu (ablution) for the five daily salah (prayers), as well as regularly performing ghusl (bathing), which led to bathhouses being built across the Islamic world.[94] Islamic toilet hygiene also requires washing with water after using the toilet, for purity and to minimize pathogens.[95]

In the Abbasid Caliphate (8th–13th centuries), its capital city of Baghdad (Iraq) had 65,000 baths, along with a sewer system.[96] Cities and towns of the medieval Islamic world had water supply systems powered by hydraulic technology that supplied drinking water along with much greater quantities of water for ritual washing, mainly in mosques and hammams (baths). Bathing establishments in various cities were rated by Arabic writers in travel guides. Medieval Islamic cities such as Baghdad, Córdoba (Islamic Spain), Fez (Morocco), and Fustat (Egypt) also had sophisticated waste disposal and sewage systems with interconnected networks of sewers. The city of Fustat also had multi-storey tenement buildings (with up to six floors) with flush toilets, which were connected to a water supply system, and flues on each floor carrying waste to underground channels.[97]

A basic form of contagion theory dates back to the Persian medicine in the medieval, where it was proposed by Persian physician Ibn Sina (also known as Avicenna) in The Canon of Medicine (1025), the most authoritative medical textbook of the Middle Ages. He mentioned that people can transmit disease to others by breath, noted contagion with tuberculosis, and discussed the transmission of disease through water and dirt.[98] The concept of invisible contagion was eventually widely accepted by Islamic scholars. In the Ayyubid Sultanate, they referred to them as najasat ("impure substances"). The fiqh scholar Ibn al-Haj al-Abdari (c. 1250–1336), while discussing Islamic diet and hygiene, gave advice and warnings about how contagion can contaminate water, food, and garments, and could spread through the water supply.[99]

In the 9th century, Ziryab invented a type of deodorant.[100] He also promoted morning and evening baths, and emphasized the maintenance of personal hygiene. Ziryab is thought to have invented a type of toothpaste, which he popularized throughout Islamic Iberia.[101] The exact ingredients of this toothpaste are not known,[102] but it was reported to have been both "functional and pleasant to taste."[101]

Sub-Saharan Africa

In West Africa, various ethnic groups such as the Yoruba have used black soap to treat skin diseases.[103]

In Southern Africa, the Zulu people conducted methods of sanitation at Ulundi.[104]

Soap and soap makers

Hard toilet soap with a pleasant smell was invented in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age when soap-making became an established industry. Recipes for soap-making are described by Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (c. 865–925), who also gave a recipe for producing glycerine from olive oil. In the Middle East, soap was produced from the interaction of fatty oils and fats with alkali. In Syria, soap was produced using olive oil together with alkali and lime. Soap was exported from Syria to other parts of the Muslim world and to Europe.[105] Two key Islamic innovations in soapmaking was the invention of bar soap, described by al-Razi, and the addition of scents using perfume technology perfected in the Islamic world.[106]

By the 15th century, the manufacture of soap in Christendom had become virtually industrialized, with sources in Antwerp, Castile, Marseille, Naples, and Venice.[107] In the 17th century the Spanish Catholic manufacturers purchased the monopoly on Castile soap from the cash-strapped Carolinian government.[108] Industrially-manufactured bar soaps became available in the late 18th century, as advertising campaigns in Europe and America promoted popular awareness of the relationship between cleanliness and health.[109]

A major contribution of the Christian missionaries in Africa,[110] China,[111] Guatemala,[112] India,[113] Indonesia,[114] Korea,[115] and other places was better health care through hygiene and introducing and distributing soap,[116] and "cleanliness and hygiene became an important marker of being identified as a Christian".[117]

Society and culture

Religious hygienic customs

Many religions require or encourage ritual purification via bathing or immersing the hands in water. In Islam, washing oneself via wudu or ghusl is necessary for performing prayer. Islamic tradition also lists a variety of rules concerning proper hygiene after using the bathroom. The Baháʼí Faith mandates the washing of the hands and face prior to the obligatory Baháʼí prayers. Orthodox Judaism requires a mikveh bath following menstruation and childbirth, while washing the hands is performed upon waking up and before eating bread. Water plays a role in Christian rituals as well,[118] and in certain denominations of Christianity such as the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church which prescribes several kinds of hand washing for example after leaving the latrine, lavatory, or bathhouse, or before prayer, or after eating a meal, or ritual handwashing.[119][118]

Etymology

First attested in English in 1676, the word hygiene comes from the French hygiène, the latinisation of the Greek ὑγιεινή (τέχνη) hygieinē technē, meaning "(art) of health", from ὑγιεινός hygieinos, "good for the health, healthy",[120] in turn from ὑγιής (hygiēs), "healthful, sound, salutary, wholesome".[121] In ancient Greek religion, Hygeia (Ὑγίεια) was the personification of health, cleanliness, and hygiene.[122]

See also

- Cleaning station – Location where aquatic life congregate to be cleaned

- Contamination control – Activities aiming to reduce contamination

- Human decontamination – Process of removing hazardous materials from the human body

- Hygiene program – Hygiene services for people experiencing homelessness

- Hygiene theater – Hygiene measures that give the illusion of safety

- Mysophobia – Pathological fear of contamination and germs

- School hygiene – cleanliness of the pupils

- Waterborne diseases – Diseases caused by pathogenic microorganisms transmitted by waters

References

- UNICEF and WHO (2021), State of the World's Hand Hygiene: A global call to action to make hand hygiene a priority in policy and practice, New York: UNICEF

- "Hygiene: Overview". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Anderson PL, Lachan JP, eds. (2008). Hygiene and its role in health. New York: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60456-195-1. OCLC 181862629.

- WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: first global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2009. ISBN 978-92-4-159790-6. OCLC 854907565.

- Lelieveld H, Holah J, Napper D, eds. (2014). Hygiene in food processing: principles and practice (2nd ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0-85709-863-4. OCLC 870650548.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wood JP, ed. (2020). Containment in the pharmaceutical industry. Boca Raton. ISBN 978-0-429-07494-3. OCLC 1148475943.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Geis PA, ed. (2020). Cosmetic microbiology: a practical approach (Third ed.). Boca Raton. ISBN 978-0-429-52443-1. OCLC 1202989365.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bloomfield SF, Exner M, Fara GM, Nath KJ, Scott EA, Van der Voorden C (2009). "The global burden of hygiene-related diseases in relation to the home and community". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- Developing and promoting hygiene in home and everyday life to meet 21st Century needs (PDF). the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. July 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-05-17.

- Bloomfield SF, Exner M, Signorelli C, Nath KJ, Scott EA (2012). "The chain of infection transmission in the home and everyday life settings, and the role of hygiene in reducing the risk of infection". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- "Show Me the Science – How to Wash Your Hands". www.cdc.gov. 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- Huang C, Ma W, Stack S (August 2012). "The hygienic efficacy of different hand-drying methods: a review of the evidence". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 87 (8): 791–8. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.019. PMC 3538484. PMID 22656243.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control (2 April 2020). "When and How to Wash Your Hands". cdc.gov.

- Bloomfield, Sally F.; Aiello, Allison E.; Cookson, Barry; O'Boyle, Carol; Larson, Elaine L. (December 2007). "The effectiveness of hand hygiene procedures in reducing the risks of infections in home and community settings including hand washing and alcohol-based hand sanitizers". American Journal of Infection Control. 35 (10): S27–S64. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2007.07.001. PMC 7115270.

- "WHO: How to handwash? With soap and water". YouTube.

- "Hand Hygiene: How, Why & When" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- "UNICEF Malawi". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- Beumer R, Bloomfield SF, Exner M, Fara GM, Nath KJ, Scott EA (2008). "Hygiene procedures in the home and their effectiveness: a review of the scientific evidence base". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- Cole E (2000). "Allergen control through routine cleaning of pollutant reservoirs in the home environment". Proceedings of Healthy Building. 4: 435–36.

- Bloomfield SF, Exner M, Signorelli C, Nath KJ, Scott EA (2011). "The infection risks associated with clothing and household linens in home and everyday life settings, and the role of laundry". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- Larson EL, Lin SX, Gomez-Pichardo C (2004). "Predictors of infectious disease symptoms in inner city households". Nurs Res. 53 (3): 190–97. doi:10.1097/00006199-200405000-00006. PMID 15167507. S2CID 46126212.

- "Recommendations for future collaboration between the U.S. and EU" (PDF). Transatlantic Taskforce on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-08.

- Bloomfield SF (2013). "Spread of Antibiotic Resistant Strains in the Home and Community". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- Maillard J, Bloomfield SF, Courvalin P, Essack SY, Gandra S, Gerba CP, Rubino JR, Scott EA (September 2020). "Reducing antibiotic prescribing and addressing the global problem of antibiotic resistance by targeted hygiene in the home and everyday life settings: A position paper". American Journal of Infection Control. 48 (9): 1090–1099. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.04.011. PMC 7165117. PMID 32311380.

- Bloomfield SF, Cookson BD, Falkiner FR, Griffith C, Cleary V (2006). "Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Clostridium difficile and ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in the home and community: assessing the problem, controlling the spread". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- "Hanging your clothes under sun OR using laundry dryer". SiOWfa15: Science in Our World: Certainty and Controversy. 2015-10-21. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- Bloomfield SF, Exner M, Signorelli C, Scott EA (2013). "Effectiveness of laundering processes used in domestic (home) settings". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

-

- "Clothing, household linens, laundry and hygiene Factsheet". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. 2013.

- "Laundry treatments at high and low temperatures". UK health and Safety Executive. 2013.

- "Home Hygiene: Prevention of infection at home and in everyday life: a learning and training resource". Home Hygiene & Health. 2018. Archived from the original on 2022-07-02.

-

- "Cleaning and disinfection: Chemical Disinfectants Explained". Home Hygiene & Health. 2014.

- Fraise AP, Maillard J, Sattar S, eds. (2013). Russell, Hugo & Ayliffe's principles and practice of disinfection, preservation and sterilization (5th ed.). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-42587-9. OCLC 825550689.

- Pickering AJ, Davis J, Boehm AB (2011-09-01). "Efficacy of alcohol-based hand sanitizer on hands soiled with dirt and cooking oil". Journal of Water and Health. 9 (3): 429–433. doi:10.2166/wh.2011.138. ISSN 1477-8920. PMID 21976190. S2CID 11800640.

- Stöppler MC. "How to Remove Ear Wax". MedicineNet.

- "Brushing & Flossing: Technique & Choosing Dental Products". www.colgate.com. Archived from the original on 2017-11-20. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- "Oral Hygiene | National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research". www.nidcr.nih.gov. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Are you brushing your teeth too hard?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 3 June 2019.

- "Brushing Your Teeth". mouthhealthy. American Dental Association.

- "How to keep your teeth clean". NHS. 26 April 2018.

- Kleist MK (2013-04-01). "Wait, Before You Brush — Why Brushing your Teeth After Eating Could be Bad for You". Naperville Magazine. Archived from the original on 2020-02-20. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- "The Medical Benefit of Daily Flossing Called Into Question". American Dental Association. Archived from the original on 2018-04-16.

- Raphael S, Blinkhorn A (25 September 2015). "Is there a place for Tooth Mousse® in the prevention and treatment of early dental caries? A systematic review". BMC Oral Health. 15 (1): 113. doi:10.1186/s12903-015-0095-6. PMC 4583988. PMID 26408042.

- Hammond C (2014-09-26). "How often do you need to see a dentist?". BBC Future.

- Irish LA, Kline CE, Gunn HE, Buysse DJ, Hall MH (October 2014). "The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 22: 23–36. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2014.10.001. PMC 4400203. PMID 25454674.

- "Healthy Sleep". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

-

- Stanwell Smith R, Bloomfield SF, Rook GA (2012). "The Hygiene Hypothesis and its Implications for Home Hygiene, Lifestyle and Public Health". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- "The Hygiene Hypothesis and its implications for home hygiene, lifestyle and public health: Summary". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. 2012.

- Bloomfield SF, Stanwell-Smith R, Crevel R, Pickup J (April 2006). "Too clean, or not too clean: the Hygiene Hypothesis and home hygiene" (PDF). Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 36 (4): 402–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02463.x. PMC 1448690. PMID 16630145.

- Rook G (11 March 2010). "99th Dahlem Conference on Infection, Inflammation and Chronic Inflammatory Disorders: Darwinian medicine and the 'hygiene' or 'old friends' hypothesis". Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 160 (1): 70–79. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04133.x. PMC 2841838. PMID 20415854.

- Texas Food Establishment Rules. Texas DSHS website: Texas Department of State Health Services. 2015. p. 6.

- "Food Safety Definition & Why is Food Safety Important". fooddocs.com. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- "Food safety". who.int. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

-

- "Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation". UNDP. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Roser, Max (2023). "Sustainable Development Goal 6: Ensure access to water and sanitation for all". Our World in Data.

- "The global burden of disease: 2004 update". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on March 24, 2009.

-

- Curtis V, Cairncross S (2003). "Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhea risk in the community: a systematic review". Lancet Infectious Diseases. 3 (5): 275–81. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00606-6. PMID 12726975.

- Aiello AE, Coulborn RM, Perez V, Larson EL (August 2008). "Effect of Hand Hygiene on Infectious Disease Risk in the Community Setting: A Meta-Analysis". American Journal of Public Health. 98 (8): 1372–81. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.124610. PMC 2446461. PMID 18556606.

- Fewtrell L, Kauffman RB, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford JM (2005). "Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhea in less developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Lancet Infectious Diseases. 5 (1): 42–52. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01253-8. PMID 15620560.

-

- Ensink J (2006). "Health impact of handwashing with soap". WELL. Archived from the original on 2010-06-19.

- Jefferson T, Foxlee R, Del Mar C, et al. (2007). "Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses: systematic review". British Medical Journal. 336 (7635): 77–80. doi:10.1136/BMJ.39393.510347.BE. PMC 2190272. PMID 18042961.

-

- Luby S, Agboatalla M, Feikin DR, Painter J, Billhimmer W, Atref A, Hoekstra RM (2005). "Effect of hand-washing on child health: a randomized control trial". Lancet. 366 (9481): 225–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66912-7. PMID 16023513. S2CID 13024434.

- Luby S, Agboatwalla M, Schnell BM, Hoekstra RM, Rahbar MH, Keswick BH (2002). "The effect of antibacterial soap on impetigo incidence, Karachi, Pakistan". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 67 (4): 430–35. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.430. PMID 12452499.

- Bloomfield SF, Nath KJ (2009). "Use of ash and mud for hand-washing in low income communities". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- "Guidelines for the prevention of infection and cross-infection in the domestic environment: focus on home hygiene issues in developing countries". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. 2002.

- Priadi CR, Putri GL, Foster T, Willetts J, Odagiri M (February 2022), Self-supply for safely managed water: To promote or to deter? (PDF)

- "Combating waterborne disease at the household level" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-03-08.

- Nath KJ, Bloomfield S, Jones M (2006). "Household water storage, handling and point-of-use treatment". International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene.

- "Water quality interventions to prevent diarrhoea: Cost and cost-effectiveness". World Health Organization. 2008. Archived from the original on September 30, 2016.

- "Household Water Treatment and Safe Storage Following Emergencies and Disasters" (PDF). World Health Organisation. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-03-01.

- "Managing water in the home". World Health Organization. 2002. Archived from the original on May 18, 2016.

- Sun J (1 July 2021). "Bathing in Ancient Times". theworldofchinese.

- Awen (30 April 2019). "Ancient Chinese Bath Culture". View of China.

- Golas PJ, Needham J (1999). Science and Civilisation in China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–91. ISBN 0-521-58000-5.

-

- "Marco Polo's Descriptions of China". Facts and Details.

- Wolff D. "Marco Polo's World". www.dianewolff.com.

- Clark S (1994). Japan: A View from the Bath. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824816575.

- "Aryan Code of Toilets (2nd Century AD)". Sulabh International Museum of Toilets.

- Ajanal M, Nayak S, Prasad BS, Kadam A (2013-10-23). "Adverse drug reaction and concepts of drug safety in Ayurveda: An overview". Journal of Young Pharmacists. 5 (4): 116–120. doi:10.1016/j.jyp.2013.10.001. ISSN 0975-1483. PMC 3930110. PMID 24563588.

- Noriega Hernández JC (2004). El baño temascal novohispano, de Moctezuma a Revillagigedo. Reflexiones sobre prácticas de higiene y expresiones de sociabilidad (PDF) (Thesis) (in Mexican Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-06. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- "Roman bath houses". Time Team. Channel Four Television Corporation. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007.

- Rutherdale M (2006). "Ordering the Bath: Children, Health, and Hygiene in Northern Canadian Communities, 1900–1970". In Warsh CK, Strong-Boag V (eds.). Children's Health Issues in Historical Perspective. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-88920-912-1.

... Thus bathing also was considered a part of good health practice. For example, Tertullian attended the baths and believed them hygienic. Clement of Alexandria, while condemning excesses, had given guidelines for Christian] who wished to attend the baths ...

- Thurlkill M (2016). Sacred Scents in Early Christianity and Islam: Studies in Body and Religion. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 6–11. ISBN 978-0-7391-7453-1.

...Clement of Alexandria (d. c. 215 CE) allowed that bathing contributed to good health and hygiene... Christian skeptics could not easily dissuade the baths' practical popularity, however; popes continued to build baths situated within church basilicas and monasteries throughout the early medieval period...

- Squatriti P (2002). Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400-1000, Parti 400–1000. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-52206-9.

...but baths were normally considered therapeutic until the days of Gregory the Great, who understood virtuous bathing to be bathing "on account of the needs of body"...

- E Clark M (2006). Contemporary Biology: Concepts and Implications. University of Michigan Press. p. 613. ISBN 9780721625973.

Douching is commonly practiced in Catholic countries. The bidet... is still commonly found in France and other Catholic countries.

- Forgione A (2013). Made in Naples: Come Napoli ha civilizzato l'Europa (e come continua a farlo) [Made in Naples. How Naples civilised Europe (And still does it)] (in Italian). Addictions-Magenes Editoriale. ISBN 978-88-6649-039-5.

- Snell M. "Middle Ages Weddings and Hygiene". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 2017-01-30. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- Penn I (2007). Dogma Evolution & Papal Fallacies. AuthorHouse. p. 223.

- "Ablutions or Bathing, Historical Perspectives". English-Word Information. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Nelson LH. "The Great Famine and the Black Death – 1315–1317, 1346–1351". Lectures in Medieval History.

- "Middle Ages Hygiene". middle-ages.org.uk.

- {{multiref2

|1=Black W (2019). The Middle Ages: Facts and Fictions. ABC-CLIO. p. 61. ISBN 9781440862328.

Public baths were common in the larger towns and cities of Europe by the twelfth century.

|2=Kleinschmidt H (2005). Perception and Action in Medieval Europe. Boydell & Brewer. p. 61. ISBN 9781843831464. - Kazhdan A, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6 |3=Kourkoutidou-Nikolaidou E, Tourta A (1997). Wandering in Byzantine Thessaloniki. Kapon Editions. p. 87. ISBN 960-7254-47-3. }}

- Régnier-Bohler D (1988). "Imagining the self". In Duby G (ed.). A History of Private Life. Vol. II. Revelations of the Medieval World. pp. 363f.

- Braunstein P (1988). "Solitude: eleventh to the thirteenth century". In Duby G (ed.). A History of Private Life. Vol. II. Revelations of the Medieval World. p. 525.

- Fresco of c. 1320 illustrated in de la Roncière C (1988). "Tuscan notables on the eve of the Renaissance". In Duby G (ed.). A History of Private Life. Vol. II. Revelations of the Medieval World. p. 232.

- Hembry P (1990). The English Spa, 1560–1815: A Social History. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press. ISBN 9780838633915.

- Bradley I (2012). Water: A Spiritual History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441167675.

- Paige JC, Harrison LW (1987). Out of the Vapors: A Social and Architectural History of Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park (PDF). U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-14.

- "Water Sanitation and Hygiene". Bill & Melinda Gates foundation. 2001. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- Matterer JL. "Daily Life". Gode Cookery: Tales of the Middle Ages. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- "History". Global Handwashing Partnership. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Majeed A (22 December 2005). "How Islam changed medicine". BMJ. 331 (7531): 1486–1487. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1486. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1322233. PMID 16373721.

- "Ṭahāra | Islam". Britannica.

- Hasan I (2006), Muslims in America, AuthorHouse, p. 144, ISBN 978-1-4259-4243-4

- Kidd J, Rees R, Tudor R (2000). Life in Medieval Times. Heinemann. p. 165. ISBN 0435325949.

- Chant C, Goodman D (2005). Pre-Industrial Cities and Technology. Routledge. pp. 136–38. ISBN 1134636202.

- Byrne JP (2012). Encyclopedia of the Black Death. ABC-CLIO. p. 29. ISBN 9781598842531.

- Reid MH (2013). Law and Piety in Medieval Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 106, 114, 189–190. ISBN 9781107067110.

- Menocal MR, Scheindlin RP, Sells MA, eds. (2000). The Literature of Al-Andalus. Cambridge University Press.

- van Sertima I (1992). The Golden Age of the Moor. Transaction Publishers. p. 267. ISBN 978-1-56000-581-0.

- Lebling RW Jr (July–August 2003). "Flight of the Blackbird". Saudi Aramco World: 24–33. Archived from the original on 2007-12-14. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303544065_Comparative_studies_on_the_effect_of_locally_made_black_soap_and_conventional_medicated_soaps_on_isolated_human_skin_microflora

- https://www.academia.edu/26731539/99_ZULU_INDIGENOUS_PRACTICES_IN_WATER_AND_SANITATION_PRELIMINARY_FIELD_RESEARCH_ON_INDIGENOUS_PRACTICES_IN_WATER_AND_SANITATION_CONDUCTED_AT_ULUNDI

- al-Hassan AY, ed. (2001). Science and Technology in Islam: Technology and applied sciences. The Different Aspects of Islamic Culture. Vol. 4. UNESCO. pp. 73–74.

- Kalın İ (2014). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 9780199812578.

- Bistline RG Jr (1996). "Anionic and Related Lime Soap Dispersants". In Stache HW (ed.). Anionic Surfactants: Organic Chemistry. Surfactant science series. Vol. 56. CRC Press. p. 632. ISBN 0-8247-9394-3.

- Gregg P (1981). King Charles I. London: Dent. p. 218. ISBN 9780460044370. OCLC 9944510.

- McNeil I (1990). An Encyclopaedia of the History of Technology. Taylor & Francis. pp. 203–205. ISBN 978-0-415-01306-2. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05.

- Newell S (2006). International Encyclopaedia of Tribal Religion: Christianity and tribal religions. Ohio University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780821417096.

- Grypma S (2008). Healing Henan: Canadian Nurses at the North China Mission, 1888–1947. University of British Columbia Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780774858212.

the Gospel of Christ was central to the 'missionary' aspect of missionary nursing, the gospel of soap and water was central to 'nursing' aspect of their works.

- Thomas K (2011). Securing the City: Neoliberalism, Space, and Insecurity in Postwar Guatemala. Duke University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9780822349587.

Christian hygiene existed (and still exists) as one small but ever important part of this modernization project. Hygiene provides an incredibly mundane, deeply routinized, marker of Christian civility ...Identifying the rural poor as 'The Great Unwashed,' Haymaker published Christian pamphlets on health and hygiene,... of personal hygiene' (filled with soap, toothpaste, and floss), attempt to shape Christian Outreach and Ethnicity.

-

- Bauman CM (2008). Christian Identity and Dalit Religion in Hindu India, 1868–1947. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 9780802862761.

Along with the use of allopathic medicine, greater hygiene was one of the most frequently mobilized markers of the boundary between Christians and other communities of Chhattisgarh... The missionaries had made no secret of preaching 'soap; along with 'salvation'...

- Baral KC (2005). Between Ethnography and Fiction: Verrier Elwin and the Tribal Question in India. North Eastern Hill University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9788125028123.

where slavery was in vogue Christianity advocated its end and personal hygiene was encouraged

- Bauman CM (2008). Christian Identity and Dalit Religion in Hindu India, 1868–1947. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 9780802862761.

- Taylor JG (2011). Cleanliness and Culture: Indonesian Histories. Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9789004253612.

Cleanliness and Godliness: These examples indicate that real cleanliness was becoming the preserve of Europeans, and, it has to be added, of Christianity. Soap became an attribute of God — or rather the Protestant

- Choi H (2009). Gender and Mission Encounters in Korea: New Women, Old Ways: Seoul-California Series in Korean Studies. Vol. 1. University of California Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780520098695.

In this way, Western forms of hygiene, health care and child rearing became an important part of creating the modern Christian in Korea.

- Channa S (2009). The Forger's Tale: The Search for Odeziaku. Indiana University Press. p. 284. ISBN 9788177550504.

A major contribution of the Christian missionaries was better health care of the people through hygiene. Soap, tooth-powder and brushes came to be used increasingly in urban areas.

- Thomas J (2015). Evangelising the Nation: Religion and the Formation of Naga Political Identity. Routledge. p. 284. ISBN 9781317413981.

cleanliness and hygiene became an important marker of being identified as a Christian

- Z Wahrman M (2016). The Hand Book: Surviving in a Germ-Filled World. University Press of New England. pp. 46–48. ISBN 9781611689556.

Water plays a role in other Christian rituals as well.... In the early days of Christianity, two to three centuries after Christ, the lavabo (Latin for "I wash myself"), a ritual handwashing vessel and bowl, was introduced as part of Church service.

- Pedersen KS (1999). "Is the Church of Ethiopia a Judaic Church?" (PDF). Warszawskie Studia Teologiczne. 12 (2): 203–216. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Liddell HG, Scott R. "ὑγιεινός". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus.

- Liddell HG, Scott R. "ὑγιής". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus.

- Liddell HG, Scott R. "ὑγίεια". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus.