Al-Adil ibn al-Sallar

Abu'l-Hasan Ali al-Adil ibn al-Sallar or al-Salar (Arabic: أبو ﺍﻟﺤﺴﻦ ﻋﻠﻲ ﺍﻟﻌﺎﺩﻝ ﺍﺑﻦ ﺍﻟﺴﻠﺎﺭ, romanized: Abu’l-Ḥasan ʿAlī al-ʿĀdil ibn al-Sallār; died 3 April 1154[1]), usually known simply as Ibn al-Sal[l]ar, was a Fatimid commander and official, who served as the vizier of Caliph al-Zafir from 1149 to 1154. A capable and brave soldier, Ibn al-Sallar assumed senior gubernatorial positions, culminating in the governorship of Alexandria. From this position in 1149 he launched a revolt, along with his stepson Abbas ibn Abi al-Futuh. Defeating the army of the then vizier, Ibn Masal, he occupied Cairo and forced the young Caliph al-Zafir to appoint him vizier instead. A mutual disdain and hatred bound the two men thereafter, and the Caliph even conspired to have Ibn al-Sallar assassinated. During this tenure, Ibn al-Sallar restored order in the army and strove to halt Crusader attacks on Egypt, but with limited success. He was assassinated at the behest of his ambitious stepson Abbas, who succeeded him as vizier.

Abu'l-Hasan Ali al-Adil ibn al-Sallar | |

|---|---|

| Died | 3 April 1154 |

| Nationality | Fatimid Caliphate |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1098–1154 |

Early life

Of Kurdish origin, Ibn al-Sallar grew up in Jerusalem, where his father was in the service of the local Artuqid governors.[1][2] Al-Adil became a follower of the Shafi'i school of Sunni Islam.[2]

Following the brief Fatimid recovery of Jerusalem in 1098, Ibn al-Sallar's father was kept in his position, and Ibn al-Sallar himself received his first official post, as commander of the elite mounted battalion (ṣubyān al-ḥajar) belonging to the Fatimid army. Ibn al-Sallar distinguished himself in battle against the Crusaders, beginning a career that led him to the governorships of Upper Egypt, al-Buhayra, and Alexandria.[2] In the latter post, he met Bullara, the widow of a Zirid prince who had died in exile in the city. To further his political ambitions, he soon married Bullara, and raised her son Abbas ibn Abi al-Futuh as his own.[1][2]

Vizierate

At the time of the death of Caliph al-Hafiz in October 1149, Ibn al-Sallar was governor of Alexandria, and his stepson Abbas was governor of the neighbouring district of al-Gharbiyya.[1][2] Ibn al-Sallar had hoped to be named vizier by the new ruler al-Zafir, but the latter chose Ibn Masal instead. Infuriated, Ibn al-Sallar refused to accept the appointment, and together with Abbas conspired against Ibn Masal. When al-Zafir learned of this plot, he called upon assistance from the grandees of the realm in support of Ibn Masal, but they proved unwilling to. In the end, the Caliph provided Ibn Masal with his own funds to hire mercenaries for action against Ibn al-Sallar.[2] Ibn al-Sallar entered Cairo on 10 December, and installed himself in the vizier's palace.[1] For the moment al-Zafir was forced to submit to the new strongman, appointing him vizier and conferring him the honorific titles al-Malik al-ʿĀdil ("righteous ruler"), al-Sayyid al-ʿAjal ("most noble master"), Amīr al-Juyūsh ("commander of the armies"), Sharaf al-Islām ("glory of Islam"), Kafī Quḍāt al-Muslimīn ("protector of the Muslims' qāḍīs"), and Hādī Duʿāt al-Muʾminīn ("guide of the believers' missionaries").[1][2]

His position was not yet secure, as Ibn Masal was among the tribes of Upper Egypt, trying to raise additional troops.[3] Furthermore, the Caliph was unreconciled to the new situation, and conspired to have Ibn al-Sallar killed. In retaliation, in January 1150 Ibn al-Sallar gathered the caliphal guard (ṣibyān al-khāṣṣ), an elite corps of cadets comprising the sons of high dignitaries and officials, and executed most of them, sending the rest to serve on the empire's frontiers.[2][4] He then sent an army under his stepson Abbas, along with Tala'i ibn Ruzzik, to confront Ibn Masal and his ally, Badr ibn Rafi. The two armies met in battle at Dalas in the province of Bahnasa on 19 February 1150, in which Ibn Masal was defeated and killed. Abbas brought his severed head back to Cairo as a token of victory.[3][4]

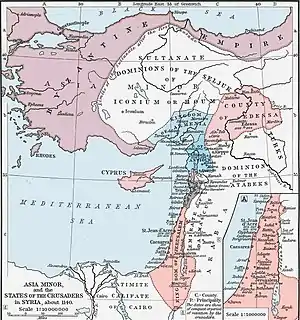

Unsurprisingly, the relationship between caliph and vizier remained extremely hostile: according to Usama ibn Munqidh, the two despised each other, with the Caliph conspiring to kill Ibn al-Sallar, and the latter seeking to depose the Caliph. The mutual hatred of both men was only kept in check by the grave external threats faced by the empire from the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem.[2] Ibn al-Sallar entertained the notion of an alliance and joint action with the Zengid ruler of Aleppo, Nur al-Din, but this did not come to pass, as the latter was focused on capturing Damascus at the time.[1] Nevertheless, following the sack of Farama by the Crusaders, in 1151/2 Ibn al-Sallar mobilized the Fatimid navy to raid Christian shipping along the coasts of the Levant from Jaffa to Tripoli, Lebanon. The fleet inflicted significant casualties and returned victorious.[2][5] This success strengthened Ibn al-Sallar's position domestically, but was hollow, as neither the Fatimids nor Nur al-Din followed it up; in contrast, in early 1153 the Crusaders launched an attack on the Fatimid outpost of Ascalon.[2]

The garrison of Ascalon comprised men of the local tribe of Kinaniyya, and a 400–600 strong cavalry force sent from Cairo every six months.[5] In March 1153, Ibn al-Sallar prepared to send reinforcements to the city, both naval and military. While the fleet was being prepared under the personal supervision of Ibn al-Sallar, the army left Cairo for Bilbays.[6] The force was led by his stepson Abbas and Usama ibn Mandiqh. According to the historian al-Maqrizi, this mission displeased Abbas, who would much rather have continued to spend his time savouring the pleasures of Cairo. His ambition inflamed by Usama, who suggested that he could become sultan of Egypt if only he so desired, Abbas decided to kill his stepfather.[2] The plot was hatched with the agreement of the Caliph.[7] Abbas sent his son Nasr, a favourite of the Caliph, back to in Cairo to stay with his grandmother in the palace of Ibn al-Sallar, ostensibly to spare him from the dangers of war. During the night Nasr entered the chamber of Ibn al-Sallar and murdered him in his sleep. He then sent a message by carrier pigeon to his father, who quickly returned to Cairo to claim the vizierate for himself, showing Ibn al-Sallar's severed head to the populace assembled before the Bab al-Dhahab gate.[2][8] Abandoned to its fate, Ascalon fell to the Crusaders in August 1153.[7]

Neither Abbas nor al-Zafir survived for long. Al-Zafir was killed by Nasr in April 1154 and replaced by his five-year old son, al-Fa'iz bi-Nasr Allah. When Abbas executed two of al-Zafir's brothers, the remaining Fatimid princes appealed to Tala'i ibn Ruzzik for aid. Abbas and Nasr were forced to flee to Syria, where Abbas was killed, while Nasr was captured by the Crusaders and handed back to the Fatimids for execution.[7]

Legacy

Historian Thierry Bianquis assesses Ibn al-Sallar as "a man of no discernible qualities whatsoever", whose greed led to "brutal and vindictive crimes", described in some detail by the chroniclers Ibn Zafir and Ibn Muyassar. These had made him widely unpopular, so that his murder was welcomed at the time.[9]

As vizier, Ibn al-Sallar raised the pay of the army, restoring its order and discipline,[2] and reactivated the Fatimid fleet, for the first time since 1125;[10] unlike the army, the fleet showed itself to be an effective force during this period.[9] Ibn al-Sallar was also active in promoting Sunni Islam in Egypt, against the Isma'ili doctrine espoused by the Fatimids: he ordered the construction of a Shafi'i madrasa in Alexandria, known as al-Adiliyya and completed in 1151/2, and may have been responsible for the appointment of the Shafi'i Abu'l-Ma'ali ibn Jumay al-Arsufi as chief qāḍī of Egypt.[11][9] He was also responsible for commissioning a number of other buildings, including several mosques and madrasas.[2]

His rise to power and downfall mark the beginning of the end for the Fatimid state: from al-Zafir on the caliphs were underage youths, sidelined and mere puppets at the hands of the strongmen who vied for the vizierate.[7] This power struggle between generals and viziers dominated the last decades of the Fatimid state, until its takeover by Saladin in 1171.[12]

References

- Wiet 1960, p. 199.

- Al-Imad 2015.

- Canard 1971, p. 868.

- Bianquis 2002, p. 382.

- Lev 1991, p. 103.

- Lev 1991, pp. 103–104.

- Daftary 1990, p. 250.

- Bianquis 2002, pp. 382–383.

- Bianquis 2002, p. 383.

- Lev 1991, p. 113.

- Lev 1991, p. 140.

- Sanders 1998, p. 154.

Sources

- Al-Imad, Leila S. (2015). "al-ʿĀdil b. al-Sallār". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Bianquis, Thierry (2002). "al-Ẓāfir bi-Aʿdāʾ Allāh". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume XI: W–Z (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 382–383. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ibn Maṣāl". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume III: H–Iram (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 868. OCLC 495469525.

- Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37019-6.

- Halm, Heinz (2014). Kalifen und Assassinen: Ägypten und der vordere Orient zur Zeit der ersten Kreuzzüge, 1074–1171 [Caliphs and Assassins: Egypt and the Near East at the Time of the First Crusades, 1074–1171] (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-66163-1.

- Lev, Yaacov (1991). State and Society in Fatimid Egypt. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004093447.

- Sanders, Paula A. (1998). "The Fatimid State, 969–1171". In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–174. ISBN 0-521-47137-0.

- Wiet, C. (1960). "al-ʿĀdil b. al-Salār". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume I: A–B (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 199. OCLC 495469456.