University of Warsaw

The University of Warsaw (Polish: Uniwersytet Warszawski, Latin: Universitas Varsoviensis) is a public research university in Warsaw, Poland. Established in 1816, it is the largest institution of higher learning in the country, offering 37 different fields of study as well as 100 specializations in humanities, technical, and the natural sciences.[10]

Uniwersytet Warszawski | |

| |

| Latin: Universitas Varsoviensis | |

Former names | Royal University of Warsaw (1816–1863) Imperial University of Warsaw (1863–1919) Józef Piłsudski University of Warsaw (1935–1945) |

|---|---|

| Type | Public |

| Established | 19 November 1816 (207 years ago) |

| Endowment | PLN 1.8 billion[1] (~US$0.4 billion) |

| Rector | Alojzy Nowak |

Academic staff | 3,974 (2021) |

Administrative staff | 3,841 (2021) |

Total staff | 7,815 (2021) |

| Students | 40,300[2] |

| Undergraduates | 44,400 (2017) |

| Postgraduates | 3,000 (2017) |

| 2,127 (2021) | |

| Location | , 00-927 Warszawa , Poland |

| Campus | Urban, 55,000 square metres (590,000 sq ft) |

| Language | Polish, English |

| Colors | |

| Nickname | AZS Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego |

Sporting affiliations | University Sports Association of Poland |

| Website | www.uw.edu.pl |

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global – Overall | |

| ARWU World[3] | 401-500 (2021) |

| QS World[4] | 284 (2023) |

| QS Employability[4] | 181-190 (2022) |

| THE World[5] | 801-1000 (2023) |

| USNWR Global[6] | 345 (2023) |

| Global – Business and economics | |

| QS Accounting[4] | 251-300 (2022) |

| QS Business[4] | 351-400 (2022) |

| QS Economics[4] | 251-300 (2022) |

| THE Business and Economics<ref"University of Warsaw". 30 October 2021.</ref> | 601+ (2022) |

| Global – Education | |

| THE Education[7] | 501+ (2022) |

| Global – Law | |

| QS Law[4] | 151-200 (2022) |

| THE Law[7] | 201+ (2022) |

| Global – Liberal arts | |

| QS Arts & Humanities[4] | 126 (2022) |

| QS Politics[4] | 101-150 (2022) |

| QS Social Sciences and Management[4] | 254 (2022) |

| THE Arts and Humanities[7] | 201-250 (2022) |

| THE Social Sciences[7] | 601+ (2022) |

| Global – Life sciences and medicine | |

| QS Life Sciences & Medicine[4] | 451-500 (2022) |

| THE Life Sciences[7] | 401-500 (2022) |

| THE Psychology[7] | 201-250 (2022) |

| Global – Science and engineering | |

| QS Chemistry[4] | 251-300 (2022) |

| QS Engineering & Tech.[4] | 251-300 (2022) |

| QS Natural Sciences[4] | 157 (2022) |

| THE Computer Science[7] | 126-150 (2022) |

| THE Physical Sciences[7] | 301-400 (2022) |

| Regional – Overall | |

| THE Europe[8] | =283 (2022) |

| THE Emerging Economies[7] | 87 (2018) |

| USNWR Europe[9] | 147 (2022) |

| National – Overall | |

| USNWR National[6] | 2 (2022) |

The University of Warsaw consists of 126 buildings and educational complexes with over 18 faculties: biology, chemistry, journalism and political science, philosophy and sociology, physics, geography and regional studies, geology, history, applied linguistics and philology, Polish language, pedagogy, economics, law and public administration, psychology, applied social sciences, management and mathematics, computer science and mechanics.

History

Beginnings under Alexander I (1816–1918)

In 1795, the partitions of Poland left Warsaw with access only to the Academy of Vilnius when the oldest and most influential Polish academic center, the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, became part of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy. In 1815, the newly established semi-autonomous polity of Congress Poland found itself without a university at all, as Vilnius was incorporated into the Russian Empire. In 1816, Alexander I permitted the Polish authorities to create a university, comprising five departments: Law and Administration, Medicine, Philosophy, Theology, and Art and Humanities. The university soon grew to 800 students and 50 professors. After most of the students and professors took part in the November 1830 Uprising the university was closed down; it was again closed after the failed January Uprising of 1863.[11] As a consequence, all Polish-language schools were prohibited by the Imperial Russian government which controlled Congress Poland. During its short existence, the university educated thousands of students, many of whom became part of the backbone of the Polish intelligentsia.[12]

In 1915, during the First World War, Warsaw was seized by German Empire and the occupying German authorities allowed a certain degree of liberalization to gain military support from the Poles. In accordance with the concept of Mitteleuropa, the Germans permitted several Polish social and educational societies to be recreated, including the University of Warsaw. The Polish language was reintroduced, but, in order to maintain Polish patriotic movement in control, the number of lecturers was kept low. No limits on the number of students; between 1915 and 1918 the number of alumni rose from a mere 1,000 to over 4,500.[13]

Second Polish Republic (1918–1939)

After Poland regained its independence in 1918, the University of Warsaw began to grow very quickly. It was reformed; all the important posts (the rector, senate, deans and councils) became democratically elected, and the state spent considerable amounts of money to modernize and equip it. Many professors returned from exile and cooperated in the effort. By the late 1920s the level of education in Warsaw had reached that of western Europe.[14]

By the beginning of the 1930s the University of Warsaw had become the largest university in Poland, with over 250 lecturers and 10,000 students. However, the financial problems of the newly reborn state did not allow for free education, and students had to pay a tuition fee for their studies (an average monthly salary, for a year). Also, the number of scholarships was very limited, and only approximately 3% of students were able to get one. Despite these economic problems, the University of Warsaw grew rapidly. New departments were opened, and the main campus was expanded.[14] After the death of Józef Piłsudski the Senate of the University of Warsaw changed its name to "Józef Piłsudski University of Warsaw" (Uniwersytet Warszawski im. Józefa Piłsudskiego). The Sanacja government proceeded to limit the autonomy of the universities. Professors and students remained divided for the rest of the 1930s as the system of segregated seating for Jewish students, known as ghetto benches, was introduced.[15]

World War II (1939–1945)

After the Polish Defensive War of 1939 the German authorities of the General Government closed all the institutions of higher education in Poland. The equipment and most of the laboratories were taken to Germany and divided amongst the German universities while the main campus of the University of Warsaw was turned into military barracks.[16]

German racial theories assumed that no education of Poles was needed and the whole nation was to be turned into uneducated serfs of the German race. Education in Polish was banned and punished with death. However, many professors organized the so-called "Secret University of Warsaw" (Tajny Uniwersytet Warszawski). The lectures were held in small groups in private apartments and the attendants were constantly risking discovery and death. However, the net of underground faculties spread rapidly and by 1944 there were more than 300 lecturers and 3,500 students at various courses.

Many students took part in the Warsaw Uprising as soldiers of the Armia Krajowa and Szare Szeregi. The German-held campus of the university was turned into a fortified area with bunkers and machine gun nests. It was located close to the buildings occupied by the German garrison of Warsaw. Heavy fights for the campus started on the first day of the Uprising, but the partisans were not able to break through the gates. Several assaults were bloodily repelled and the campus remained in German hands until the end of the fights. During the uprising and the occupation 63 professors were killed, either during fights or as an effect of German policy of extermination of Polish intelligentsia. The university lost 60% of its buildings during the fighting in 1944. A large part of the collection of priceless works of art and books donated to the university was either destroyed or transported to Germany, never to return.

Post-war and the People's Republic (1945–1989)

After World War II it was not clear whether the university would be restored or whether Warsaw itself would be rebuilt. However, many professors who had survived the war returned, and began organizing the university from scratch. In December 1945, lectures resumed for almost 4,000 students in the ruins of the campus, and the buildings were gradually rebuilt. Until the late 1940s the university remained relatively independent. However, soon the communist authorities started to impose political controls, and the period of Stalinism started. Many professors were arrested by the Urząd Bezpieczeństwa (Secret Police), the books were censored and ideological criteria in employment of new lecturers and admission of students were introduced. On the other hand, education in Poland became free of charge and the number of young people to receive the state scholarships reached 60% of all the students. After Władysław Gomułka's rise to power in 1956, a brief period of liberalization ensued, though communist ideology still played a major role in most faculties (especially in such faculties as history, law, economics, and political science). International cooperation was resumed and the level of education rose.[17]

By the mid-1960s the government started to suppress freedom of thought, which led to increasing unrest among the students. A political struggle within the communist party prompted Zenon Kliszko to ban the production of Dziady by Mickiewicz at the Teatr Narodowy, leading to 1968 Polish political crisis coupled with anti-Zionist and anti-democratic campaign and the outbreak of student demonstrations in Warsaw, which were brutally crushed – not by police, but by the ORMO reserve militia squads of plain-clothed workers.[18] As a result, a large number of students and professors were expelled from the university. Nonetheless, the university remained the centre of free thought and education. What professors could not say during lectures, they expressed during informal meetings with their students. Many of them became leaders and prominent members of the Solidarity movement and other societies of the democratic opposition which led to the collapse of communism. The scientists working at the University of Warsaw were also among the most prominent printers of books forbidden by censorship.[19]

Third Polish Republic (1989–present)

In 1999, a new University of Warsaw Library building was opened in Powiśle.[20]: 43 After Poland joined the European Union in 2004, the university obtained additional funds from the European Structural and Investment Funds for the construction of additional buildings including the Biological and Chemical Research Centre, Centre of New Technologies, and a new building for the Faculty of Physics.[20]: 5

In recent years, the University of Warsaw has been ranked among best Polish universities. It was ranked by Perspektywy magazine as the best Polish university in 2010, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2019, and 2022.[21][22][23] ARWU ranked the university as the best Polish higher level institution in 2012, 2017, 2018, and 2020.[24] The university is especially well-regarded in science. ARWU ranked the mathematics and physics branches of the institution in the global top 150 and top 75, respectively, in 2022.[24]

Campus

University of Warsaw owns a total of 126 buildings. Further construction and a vigorous renovation program are underway at the main campus. The university is spread out over the city, though most of the buildings are concentrated in two areas.

Main campus

The main campus of the University of Warsaw is in the city center, adjacent to the Krakowskie Przedmieście street. It comprises several historic palaces, most of which had been nationalized in the 19th century. The chief buildings include:

- Kazimierzowski Palace (Pałac Kazimierzowski) – the seat of the rector and the Senate;

- Uruski Palace (Pałac Uruskich) – left side of main gate entrance, houses the Department of Geography and Regional Studies

- the Old Library (Stary BUW) – since recent refurbishment, a secondary lecture building;

- the Main School (Szkoła Główna) – former seat of the Main School until the January 1863 Uprising, later the faculty of biology; now, since its refurbishment, the seat of the Institute of archaeology;

- Auditorium Maximum – the main lecture hall, with seats for several hundred students.

The Warsaw University Library building is a short walk downhill from the main campus, in the Powiśle neighborhood.[25]

Natural sciences campus

The second important campus is located near Banacha and Pasteura streets. It is home to the departments of chemistry, physics, biology, mathematics, computer science, and geology, and contains several other university buildings such as the Interdisciplinary Centre for Mathematical and Computational Modelling, the Environmental Heavy Ion Laboratory that houses a cyclotron and a facility for the production of PET radiopharmaceuticals, and a sports facility. Several new buildings have been constructed within this campus in recent years, and the Department of Physics moved here from its previous location at Hoża Street.

Together with buildings of other institutions, such as the Institute of Experimental Biology, Radium Institute and the Medical University of Warsaw, the campus is part of an almost contiguous area of scientific and educational facilities covering approximately 43 hectares (110 acres).

Faculties

- Faculty of Applied Linguistics[26]

- Faculty of Applied Social Sciences and Resocialization[27]

- Faculty of Archaeology

- Faculty of "Artes Liberales"

- Faculty of Biology[28]

- Faculty of Chemistry[29]

- Faculty of Culture and Arts

- Faculty of Economic Sciences[30]

- Faculty of Education

- Faculty of Geography and Regional Studies[31]

- Faculty of Geology[32]

- Faculty of History[33]

- Faculty of Journalism, Information and Book Studies

- Faculty of Law and Administration[34]

- Faculty of Management[35]

- Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Mechanics[36]

- Faculty of Modern Languages

- Faculty of Oriental Studies[37]

- Faculty of Sociology

- Faculty of Philosophy

- Faculty of Physics[38]

- Faculty of Polish Studies

- Faculty of Political Science and International Studies[39]

- Faculty of Psychology[40]

Other institutes

- American Studies Center

- British Studies Centre

- Centre de Civilisation Française et d'Études Francophones auprès de l'Université de Varsovie

- Centre for Archaeological Research at Novae

- Centre for Environmental Study

- Centre for Europe

- Centre for European Regional and Local Studies (EUROREG)[41]

- Centre for Foreign Language Teaching

- Centre for Inter-Faculty Individual Studies in the Humanities[42]

- Centre for Latin-American Studies (CESLA)

- Centre for Open Multimedia Education

- Centre for the Study of Classical Tradition in Poland and East-Central Europe

- Centre of Studies in Territorial Self-Government and Local Development

- Chaire UNESCO du Developpement Durable de l`Universite de Vaersovie

- Comité Polonais de l'Alliance Français

- Digital Economy Lab (DELab) – joint institute with Google[43]

- Erasmus of Rotterdam Chair

- Heavy Ion Laboratory

- Individual Inter-faculty Studies in Mathematics and Natural Sciences[44]

- Institute of Americas and Europe

- Institute of International Relations – host of GMAPIR

- The Robert B.Zajonc Institute for Social Studies[45]

- Inter-faculty Study Programme in Environmental Protection

- Interdisciplinary Centre for Behavioural Genetics

- Interdisciplinary Centre for Mathematical and Computational Modelling[46]

- Physical Education and Sports Centre

- Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology

- University Centre for Technology Transfer

- University College of English Language Teacher Education

- University of Warsaw for Foreign Language Teacher Training and European Education

Institutions

The university in popular culture

- In Ian Fleming's 1961 novel Thunderball, the ninth book in the James Bond series, one of the main characters, Ernst Stavro Blofeld who is the head of the global criminal organisation SPECTRE, is said to be a graduate of the University of Warsaw.[51]

- In 2016, the Polish Post issued commemorative stamps on the 200th anniversary of the founding of the university depicting the Column Hall of the building of the Faculty of History.[52]

Notable people

Alumni

- Jan Albrecht (born 1944), neurobiologist

- Jerzy Andrzejewski (1909–1983), author

- Szymon Askenazy (1865-1935), Polish jurist, historian, educator, first Polish representative to the League of Nations

- Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński (1921–1944), poet, Home Army soldier killed in the Warsaw Uprising

- Menachem Begin (1913–1992), 6th Prime Minister of Israel (1977–1983), Nobel Peace Prize winner (1978)

- Marek Bieńczyk (born 1956), writer, historian of literature, essayist and translator, Nike Award winner (2012)

- Adam Bodnar (born 1977), lawyer, human rights activist, Polish Ombudsman

- Draginja Nadażdin (born 1975) director, Amnesty International Poland

- Tadeusz Borowski (1922–1951), poet, writer

- Kazimierz Brandys (1916–2000), writer

- Marian Brandys (1912–1998), writer, journalist

- Andrzej Buras (born 1946), Danish physicist, recipient of 2020 Max Planck Medal

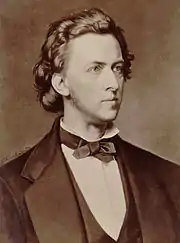

- Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849), pianist, composer

- Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz (born 1950), politician, Prime Minister of Poland (1996–1997), Marshal of the Sejm (2005)

- Tomasz Dietl (born 1950), physicist

- Samuel Eilenberg (1913–1998), mathematician, computer scientist, art collector

- Barbara Engelking (born 1962), sociologist

- Joseph Epstein (1911–1944), communist leader of French resistance

- Lech Gardocki (born 1944) lawyer, judge, former First President of the Supreme Court of Poland

- Krzysztof Gawędzki (1947–2022), mathematical physicist

- Marek Gazdzicki (born 1956), nuclear physicist

- Bronisław Geremek (1932–2008), historian, politician

- Małgorzata Gersdorf (born 1952), lawyer, first President of the Supreme Court of Poland

- Maciej Gliwicz (born 1939), biologist

- Witold Gombrowicz (1904–1969), writer

- Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz (born 1952), politician, President of the National Bank of Poland (1992–2001), Mayor of Warsaw (2006–2018)

- Jan T. Gross (born 1947), historian, writer, Princeton University professor

- Jarek Gryz computer scientist, data analyst

- Zofia Helman (born 1937), musicologist

- Gustaw Herling-Grudziński (1919–2000), journalist, writer, Gulag survivor

- Leonid Hurwicz (1917–2008), economist, mathematician, Nobel Prize in Economics (2007)

- Maria Janion (1926–2020), literary critic

- Monika Jaruzelska (born 1963) fashion designer, journalist, daughter of former Polish President Wojciech Jaruzelski

- Jerzy Jedlicki (1930–2018), historian of ideas, anti-communist activist

- Jarosław Kaczyński (born 1949), politician, Prime Minister of Poland (2006–2007)

- Lech Kaczyński (1949–2010), politician, Mayor of Warsaw (2002–2005), President of Poland (2005–2010)

- Andrzej Kalwas (born 1936), lawyer, businessman, and former Polish Minister of Justice

- Aleksander Kamiński (1903–1978), writer, leader of Polish Scouting and Guiding Association

- Ryszard Kapuściński (1932–2007), writer and journalist

- Mieczysław Karłowicz (1876–1909), composer

- Jan Karski (1914–2000), Polish resistance fighter

- Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska (1925–2015), paleobiologist

- Leszek Kołakowski (1927–2009), philosopher, historian of philosophy

- Bronisław Komorowski (born 1952), politician, Marshal of the Sejm (2007–2010), President of Poland (2010–2015)

- Alpha Oumar Konaré, (born 1946), 3rd President of Mali (1992–2002)

- Wojciech Kopczuk, Columbia University economist

- Janusz Korwin-Mikke (born 1942), conservative-liberal politician and journalist

- Marek Kotański (1942–2002), psychologist and streetworker

- Jacek Kuroń (1934–2004), historian, author, social worker, and politician

- Jan Józef Lipski (1926–1991), literature historian, politician

- Ewa Łętowska (born 1940), lawyer, first Polish Ombudsman for Citizen Rights

- Jerzy Łojek (1932–1986), historian, writer

- Olga Malinkiewicz (born 1982), physicist

- Tadeusz Mazowiecki (1927–2013), author, social worker, journalist, Prime Minister of Poland (1989–1991)

- Adam Michnik (born 1946), journalist

- Karol Modzelewski (1937–2019), historian, politician

- Mirosław Nahacz (1984–2007), novelist, screenwriter[53]

- Jerzy Neyman (1894–1981), mathematician, statistician, University of California professor

- Jan Olszewski (1930-2019), lawyer, politician, Prime Minister of Poland (1991–1992)

- Janusz Onyszkiewicz (born 1937), politician

- Maria Ossowska (1896–1974), sociologist

- Bohdan Paczyński (1940–2007), astronomer

- Rafał Pankowski (born 1976), sociologist and political scientist

- Longin Pastusiak (born 1935), politician, Marshal of the Senate of the Republic of Poland (2001–2005)

- Bolesław Piasecki (1915–1979), politician

- Krzysztof Piesiewicz (born 1945), lawyer, screenwriter

- Marian Pilot (born 1936), writer, journalist and screenwriter, Nike Award winner (2011)

- Moshe Prywes (1914–1998), Israeli physician and educator; first President of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

- Adam Przeworski (born 1940), political scientist, New York University professor

- Bolesław Prus (1847–1912), writer

- Mikhail Reisner (1868-1928), Russian and Soviet jurist, historian and academic.

- Emanuel Ringelblum (1900–1944), historian, founder Emanuel Ringelblum Archives of Warsaw Ghetto[54]

- Ireneusz Roszkowski (1910–1996), precursor of prenatal medicine

- Józef Rotblat (1908–2005), physicist, Nobel Peace Prize (1995)

- Agata Różańska (born 1968), astronomer and astrophysicist

- Stefan Sarnowski (1939-2014), philosopher

- Stanisław Sedlaczek (1892–1941), social worker, leader of Polish Scouting and Guiding Association

- Yitzhak Shamir (1915–2012), 7th Prime Minister of Israel (1983–1984 and 1986–1992)

- Wacław Sierpiński (1882–1969), mathematician

- Andrzej Sobolewski (born 1951), physicist

- Alexander Soloviev (1890-1971) Russian émigré jurist, historian, academic.

- Dmitry Strelnikoff (born 1969), Russian writer, biologist, journalist for the media

- Kazimiera Szczuka (born 1966), literary critic, feminist, LGBT rights activist, television personality

- Adam Szymczyk (born 1970), art critic and curator

- Magdalena Środa (born 1957), philosopher and feminist

- Alfred Tarski (1902–1982), logician, mathematician, member of the Lwów-Warsaw school of logic

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz (1886–1980), philosopher, historian of esthetics

- Olga Tokarczuk (born 1962), writer, essayist, psychologist, Nobel Prize in Literature (2018)

- Rafał Trzaskowski (born 1972), politician, academic teacher, Mayor of Warsaw

- Julian Tuwim (1894–1953), poet and writer

- Alfred Twardecki (born 1962), archaeologist, historian of antiquity, museologist

- Andrzej Udalski (born 1957), astronomer and astrophysicist

- Mordkhe Veynger (1890–1929), Soviet-Jewish linguist

- Kostiantyn Voblyi (1876-1947), Ukrainian economist, academic, active in the Russian Empire and Soviet Union.

- Andrzej Kajetan Wróblewski (born 1933), experimental physicist

- Janusz Andrzej Zajdel (1938–1985), physicist and science-fiction writer

- Ludwik Zamenhof (1859–1917), physician, inventor of Esperanto

- Andrzej Zaniewski (born 1939), author and poet

- Paweł Zarzeczny (1961–2017), sports journalist, columnist and TV personality

- Anna Zawadzka (1919–2004), social worker, leader of Polish Scouting and Guiding Association

- Maciej Zembaty (1944–2011), poet, writer, translator of Leonard Cohen's works

- Rafał A. Ziemkiewicz (born 1964), writer

- Florian Znaniecki (1882–1958), philosopher and sociologist

Staff

Professors

- Osman Achmatowicz (1899–1988), chemist, rector of the Technical University of Łódź (1946–1953)

- Vladimir Prokhorovich Amalitskii (1860–1917), paleontologist

- Szymon Askenazy (1866–1935), historian

- Aleksandr Nikolaevich Bartenev (1882-1946), zoologist

- Maria Ludwika Bernhard (1908–1998), archaeologist

- Karol Borsuk (1905–1982), mathematician

- Franciszek Bujak (1919–1921) historian

- Jan Niecisław Baudouin de Courtenay (1845–1929), linguist, introduced the concept of a phoneme

- Zygmunt Bauman (1925–2017), sociologist

- Tomasz Dietl (born 1950), physisct, Laureate of Agilient Technologies Europhysics Prize of The European Physical Society (2005)

- Samuel Dickstein (1851-1939), mathematician, proponent of Jewish assimilation in Poland

- Benedykt Dybowski (1833–1930), biologist and explorer of Siberia and Baikal area

- Aleksandr Mikhailovich Evlakhov (1880-1966), literary critic

- Michel Foucault (1926–1984), French philosopher, at the university dean-faculty of the French Centre 1958–1959

- Stanisław Grabski (1871–1949), economist

- Dmitri Iosifovich Ivanovsky (1864-1920), botanist, pioneer in the discovery and study of viruses

- Henryk Jabłoński (1909–2003), historian, nominal head of state of Poland (1972–1985)

- Feliks Pawel Jarocki (1790–1865), zoologist

- Barbara Jaruzelska (1931–2017), philologist and German studies professor, First Lady of Poland (1985–1990)

- Nikolai Ivanovich Kareev (1850-1931), philosopher, historian

- Yefim Fyodorovich Karsky (1861-1931) linguist, ethnographer, paleographer

- Jerzy Kolendo (1955-1983), classical archaeologist and historian

- Leszek Kołakowski (1927–2009), philosopher

- Kazimierz Kuratowski (1896–1980), mathematician

- Joachim Lelewel (1786–1861), historian, politician and freedom fighter

- Antoni Leśniowski (1867–1940), surgeon and medic, one of the discoverers of Crohn's disease

- Edward Lipiński (1888–1986), economist, founder of the Main Statistical Office

- Jan Łukasiewicz (1878–1956), mathematician and logician

- Mieczysław Maneli (1922–1994), jurist

- Leszek Marks (born 1951), geologist

- Kazimierz Michałowski (1901–1981), archaeologist, explorer of Deir el Bahari and Faras

- Andrzej Mostowski (1913–1975), mathematician

- Nikolai Viktorovich Nasonov (1855-1939), zoologist

- Maria Ossowska (1896–1974), sociologist

- Stanisław Ossowski (1897–1963), sociologist

- Vladimir Ivanovich Palladin (1859-1922), biochemist, botanist

- Grigol Peradze (1899–1942), Orthodox theologian

- Leon Petrażycki (1867–1931), jurist, philosopher and logician, one of the founders of sociology of law

- Ladislaus Pilars de Pilar (1874–1952), literature professor, poet and entrepreneur

- Adam Podgórecki (1925–1998), sociologist of law

- Dmitry Yakovlevich Samokvasov (1843-1911), archaeologist, legal historian

- Henryk Samsonowicz (1930–2021), historian, rector (1980–1982)

- Wacław Sierpiński (1882–1969), mathematician

- Alfred Sokołowski (1849–1924), physician and a pioneer in tuberculosis treatment

- Hélène Sparrow (1891–1970), bacteriologist and public health pioneer, especially typhus

- Nikolay Yakovlevich Sonin (1849–1915), mathematician

- Jan Strelau (born 1931), psychologist

- Jerzy Szacki (1929–2016), sociologist and historian

- Andrzej K. Tarkowski (born 1933), zoologist, Laureate of Japan Prize (2002)

- Stanisław Thugutt (1873–1941), politician, rector (1919–1920)

- Georgy Feodosevich Voronoy (1868-1908), mathematician

- Tadeusz Wałek-Czarnecki (1889–1949), professor of Ancient History

- Ewa Wipszycka (born 1933), historian and papyrologist

- Władysław Witwicki (1878–1948), psychologist, philosopher, translator and artist

- Georgy Viktorovich Wulff (1863-1925), crystallographer

- Włodzimierz Zonn (1905–1985), astronomer

Rectors

- Wojciech Szweykowski (1818–1831)

- Józef Karol Skrodzki (1831)

- Józef Mianowski (1862–1869)

- Piotr Ławrowski (1869–1873)

- Nikołaj Błagowieszczański (1874–1884)

- Nikołaj Ławrowski (1884–1890)

- Michaił Szałfiejew (1895)

- Pawieł Kowalewski (1896)

- Grigorij Zenger (1896)

- Michaił Szałfiejew (1898)

- Grigorij Uljanow (1899–1903)

- Piotr Ziłow (1904)

- Yefim Karskiy (1905–1911)

- Wasilij Kudrewiecki (1911–1912)

- Iwan Trepicyn (1913)

- Siergiej Wiechow (1914–1915)

- Józef Brudziński (1915–1917)

- Antoni Kostanecki (1917–1919)

- Stanisław Thugutt (1919–1920)

- Jan Karol Kochanowski (1920–1921)

- Jan Mazurkiewicz (1921–1922)

- Jan Łukasiewicz (1922–1923)

- Ignacy Koschembahr-Łyskowski (1923–1924)

- Franciszek Krzyształowicz (1924–1925)

- Stefan Pieńkowski (1925–1926)

- Bolesław Hryniewiecki (1926–1927)

- Antoni Szlagowski (1927–1928)

- Gustaw Przychocki (1928–1929)

- Tadeusz Brzeski (1929–1930)

- Mieczysław Michałowicz (1930–1931)

- Jan Łukasiewicz (1931–1932)

- Józef Ujejski (1932–1933)

- Stefan Pieńkowski (1933–1936)

- Włodzimierz Antoniewicz (1936–1939)

- Jerzy Modrakowski (1939)

- Stefan Pieńkowski (1945–1947)

- Franciszek Czubalski (1947–1949)

- Jan Wasilkowski (1949–1952)

- Stanisław Turski (1952–1969)

- Zygmunt Rybicki (1969–1980)

- Henryk Samsonowicz (1980–1982)

- Kazimierz Albin Dobrowolski (1982–1985)

- Rector electus Klemens Szaniawski (1984)

- Grzegorz Białkowski (1985–1989)

- Andrzej Kajetan Wróblewski (1989–1993)

- Włodzimierz Siwiński (1993–1999)

- Piotr Węgleński (1999–2005)

- Katarzyna Chałasińska-Macukow (2005–2012)

- Marcin Pałys (2012–2020)

- Alojzy Nowak (since 2020)

Staff

- Czesław Miłosz – janitor at Warsaw University Library during World War II; recipient of 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature.[55]

See also

Notes

- "Facts and figures". uw.edu.pl.

- "University of Warsaw – Facts and figures". en.uw.edu.pl.

- "ShanghaiRanking's Academic Ranking of World Universities".

- "University of Warsaw". Top Universities.

- "University of Warsaw". Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- "Best Global Universities in Poland". usnews.com. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- "University of Warsaw". 30 October 2021.

- "Best universities in Europe 2022". 22 September 2021.

- "2022-2023 Best Global Universities in Europe". usnews. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- Redakcja (2012). "About Us". University of Warsaw (UW) homepage (in Polish and English). Uniwersytet Warszawski, Warsaw. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- "University of Warsaw history (1816–1831), homepage". Archived from the original on January 9, 2013.

- "University of Warsaw history (1857–1869), homepage". Archived from the original on January 9, 2013.

- "University of Warsaw history (1915–1918), homepage". Archived from the original on January 9, 2013.

- "University of Warsaw history (1918–1935), homepage". Archived from the original on January 9, 2013.

- Markusz, Katarzyna (2019-10-08). "University of Warsaw students remember pre-WWII segregation of Jews". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2023-01-11.

- "University of Warsaw history (1939–1944)" (in Polish). Uw.edu.pl. Archived from the original on 2013-01-09.

- "University of Warsaw history (1945–1956), homepage". Archived from the original on January 9, 2013.

- "March '68". Exhibition. Institute of National Remembrance. pp. 1–2. Introduction, followed by scans of articles. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

The Voluntary Reserves of the Citizens' Militia (armed with cable and truncheons) beating the students, were met with shouts of "Gestapo!", "Gestapo!"

- "University of Warsaw history (1956–1989), homepage". Archived from the original on January 9, 2013.

- Łukaszewska, Katarzyna; Swatowska, Anna; Bieńko, Katarzyna; Korzekwa-Józefowicz, Anna; Laska, Olga (2018). University of Warsaw Main Sites, Facts and Figures Guidebook (PDF). ISBN 978-83-235-3014-5.

- University Ranking at Perspektywy.pl Ranking uczelni akademickich 2011 with index. (in Polish).

- University Ranking at Perspektywy.pl Ranking uczelni akademickich 2014 (in Polish)

- "Ranking Uczelni Akademickich – Ranking Szkół Wyższych PERSPEKTYWY 2016". www.perspektywy.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- "University of Warsaw". www.shanghairanking.com. Retrieved 2022-12-30.

- "10 lat Biblioteki Uniwersyteckiej na Powiślu" (in Polish). Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Strona Wydziału Lingwistyki Stosowanej". www.wls.uw.edu.pl.

- "Select registration - IRK". www.irk.uw.edu.pl.

- "Strona Wydziału Biologii UW". Biol.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Faculty of Chemistry, Warsaw University". Archived from the original on 2004-04-01. Retrieved 2004-05-03.

- "Wydział Nauk Ekonomicznych – Uniwersytet Warszawski". Wne.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Wydział Geografii i Studiów Regionalnych Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego" (in Polish). Wgsr.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Wydział Geologii Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego" (in Polish). Geo.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Wydział Historyczny UW". Wh.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Faculty of Law and Administration". En.wpia.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- Marcin Jędra (2012-05-26). "Wydział Zarządzania Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, zarządzanie, studia podyplomowe, studia licencjackie, studia magisterskie". Wz.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Wydział MIM UW – Strona główna". Mimuw.edu.pl. Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Wydział Orientalistyczny UW – Strona Wydziału Orientalistycznego Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego".

- Faculty of Physics University of Warsaw (in English)

- "Wydział Nauk Politycznych i Studiów Międzynarodowych – Strona główna". wnpism.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- Psychologia.pl (in Polish) and Psychology.pl (in English)

- "Centre for European Regional and Local Studies (EUROREG)". Euroreg.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- "Kolegium MISH UW". Mish.uw.edu.pl. 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Digital Economy Lab (DELab)" (in Polish). uw.edu.pl. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- "MISMaP – MiÄ™dzywydziaÅ'owe Indywidualne Studia Matematyczno-Przyrodnicze UW – MISMaP". Mismap.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- "Witamy w ISS" (in Polish). Iss.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "Strona Główna". icm.edu.pl. Archived from the original on 2008-02-22. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- "O Radiu - Radio Kampus 97,1 FM #SAMESZTOSY".

- History of the Institute. The Internet Archive. (in English)

- "Polonicum.uw.edu.pl". Archived from the original on April 5, 2004.

- Buwcd.buw.uw.edu.pl Archived April 6, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Bond Film Informant: Ernst Stavro Blofeld". Mjnewton.demon.co.uk. 28 May 2008. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "200 lat Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego" (in Polish). Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Sajewicz, Natalia (May 2017). "Mirosław Nahacz". Culture.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- Emanuel Ringelblum: The Creator of "Oneg Shabbat" Holocaust Research Project.

- Haven, Cynthia L. (2006). Czesław Miłosz: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. XXV. ISBN 9781578068296.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)