Adam Mickiewicz

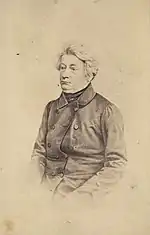

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (Polish pronunciation: [ˈadam mit͡sˈkʲɛvit͡ʂ] ⓘ; 24 December 1798 – 26 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Romanticism, he is one of Poland's "Three Bards" (Polish: Trzej Wieszcze)[1] and is widely regarded as Poland's greatest poet.[2][3][4] He is also considered one of the greatest Slavic[5] and European[6] poets and has been dubbed a "Slavic bard".[7] A leading Romantic dramatist,[8] he has been compared in Poland and Europe to Byron and Goethe.[7][8]

Adam Mickiewicz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Adam Bernard Mickiewicz 24 December 1798 Zaosie, Lithuania Governorate, Russian Empire (modern-day Belarus) |

| Died | 26 November 1855 (aged 56) Istanbul, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey) |

| Resting place | Wawel Cathedral, Kraków |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | Polish |

| Genre | Romanticism |

| Notable works | Pan Tadeusz Dziady |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 6 |

| Signature | |

He is known chiefly for the poetic drama Dziady (Forefathers' Eve) and the national epic poem Pan Tadeusz. His other influential works include Konrad Wallenrod and Grażyna. All these served as inspiration for uprisings against the three imperial powers that had partitioned the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth out of existence.

Mickiewicz was born in the Russian-partitioned territories of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which had been part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and was active in the struggle to win independence for his home region. After, as a consequence, spending five years exiled to central Russia, in 1829 he succeeded in leaving the Russian Empire and, like many of his compatriots, lived out the rest of his life abroad. He settled first in Rome, then in Paris, where for a little over three years he lectured on Slavic literature at the Collège de France. He was an active activist striving for a democratic and independent Poland. He died, probably of cholera, at Istanbul in the Ottoman Empire, where he had gone to help organize Polish forces to fight Russia in the Crimean War.

In 1890, his remains were repatriated from Montmorency, Val-d'Oise, in France, to Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, Poland.

Life

Early years

Adam Mickiewicz was born on 24 December 1798, either at his paternal uncle's estate in Zaosie (now Zavosse) near Navahrudak (in Polish, Nowogródek) or in Navahrudak itself[a] in what was then part of the Russian Empire and is now Belarus. The region was on the periphery of Lithuania proper and had been part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania until the Third Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1795).[9][10] Its upper class, including Mickiewicz's family, were either Polish or Polonized.[9] The poet's father, Mikołaj Mickiewicz, a lawyer, was a member of the Polish[11] nobility (szlachta)[12] and bore the hereditary Poraj coat-of-arms;[13] Adam's mother was Barbara Mickiewicz, née Majewska. Adam was the second-born son in the family.[14]

Mickiewicz spent his childhood in Navahrudak,[12][14] initially taught by his mother and private tutors. From 1807 to 1815 he attended a Dominican school following a curriculum that had been designed by the now-defunct Polish Commission of National Education, which had been the world's first ministry of education.[12][14][15] He was a mediocre student, although active in games, theatricals, and the like.[12]

In September 1815, Mickiewicz enrolled at the Imperial University of Vilnius, studying to be a teacher.[16] After graduating, under the terms of his government scholarship, he taught secondary school at Kaunas from 1819 to 1823.[14]

In 1818, in the Polish-language Tygodnik Wileński (Wilno Weekly), he published his first poem, Zima miejska (City Winter).[17] The next few years would see a maturing of his style from sentimentalism/neoclassicism to romanticism, first in his poetry anthologies published in Vilnius in 1822 and 1823; these anthologies included the poem Grażyna and the first-published parts (II and IV) of his major work, Dziady (Forefathers' Eve).[17] By 1820 he had already finished another major romantic poem, Oda do młodości (Ode to Youth), but it was considered to be too patriotic and revolutionary for publication and would not appear officially for many years.[17]

About the summer of 1820, Mickiewicz met the love of his life, Maryla Wereszczakówna. They were unable to marry due to his family's poverty and relatively low social status; in addition, she was already engaged to Count Wawrzyniec Puttkamer, whom she would marry in 1821.[17][18]

Imprisonment and exile

In 1817, while still a student, Mickiewicz, Tomasz Zan and other friends had created a secret organization, the Philomaths.[17] The group focused on self-education but had ties to a more radical, clearly pro-Polish-independence student group, the Filaret Association.[17] An investigation of secret student organizations by Nikolay Novosiltsev, begun in early 1823, led to the arrests of a number of students and ex-student activists including Mickiewicz, who was taken into custody and imprisoned at Vilnius' Basilian Monastery in late 1823 or early 1824 (sources disagree as to the date).[17] After investigation into his political activities, specifically his membership in the Philomaths, in 1824 Mickiewicz was banished to central Russia.[17] Within a few hours of receiving the decree on 22 October 1824, he penned a poem into an album belonging to Salomea Bécu, the mother of Juliusz Słowacki.[19] (In 1975 this poem was set to music in Polish and Russian by Soviet composer David Tukhmanov.)[20] Mickiewicz crossed the border into Russia about 11 November 1824, arriving in Saint Petersburg later that month.[17] He would spend most of the next five years in Saint Petersburg and Moscow, except for a notable 1824 to 1825 excursion to Odessa, then on to Crimea.[21] That visit, from February to November 1825, inspired a notable collection of sonnets (some love sonnets, and a series known as Crimean Sonnets, published a year later).[17][21][22]

Mickiewicz was welcomed into the leading literary circles of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, where he became a great favourite for his agreeable manners and an extraordinary talent for poetic improvisation.[22] The year 1828 saw the publication of his poem Konrad Wallenrod.[22] Novosiltsev, who recognized its patriotic and subversive message, which had been missed by the Moscow censors, unsuccessfully attempted to sabotage its publication and to damage Mickiewicz's reputation.[13][22]

In Moscow, Mickiewicz met the Polish journalist and novelist Henryk Rzewuski and the Polish composer and piano virtuoso Maria Szymanowska, whose daughter, Celina Szymanowska, Mickiewicz would later marry in Paris, France. He also befriended the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin[22] and Decembrist leaders including Kondraty Ryleyev.[21] It was thanks to his friendships with many influential individuals that he was eventually able to obtain a passport and permission to leave Russia for Western Europe.[22]

European travels

After serving five years of exile to Russia, Mickiewicz received permission to go abroad in 1829. On 1 June that year, he arrived in Weimar in Germany.[22] By 6 June he was in Berlin, where he attended lectures by the philosopher Hegel.[22] In February 1830 he visited Prague, later returning to Weimar, where he received a cordial reception from the writer and polymath Goethe.[22]

He then continued on through Germany all the way to Italy, which he entered via the Alps' Splügen Pass.[22] Accompanied by an old friend, the poet Antoni Edward Odyniec, he visited Milan, Venice, Florence and Rome.[22][23] In August that same year (1830) he went to Geneva, where he met fellow Polish Bard Zygmunt Krasiński.[23] During these travels he had a brief romance with Henrietta Ewa Ankwiczówna, but class differences again prevented his marrying his new love.[23]

Finally about October 1830 he took up residence in Rome, which he declared "the most amiable of foreign cities."[23] Soon after, he learned about the outbreak of the November 1830 Uprising in Poland, but he would not leave Rome until the spring of 1831.[23]

On 19 April 1831 Mickiewicz departed Rome, traveling to Geneva and Paris and later, on a false passport, to Germany, via Dresden and Leipzig arriving about 13 August in Poznań (German name: Posen), then part of the Kingdom of Prussia.[23] It is possible that during these travels he carried communications from the Italian Carbonari to the French underground, and delivered documents or money for the Polish insurgents from the Polish community in Paris, but reliable information on his activities at the time is scarce.[23][24] Ultimately he never crossed into Russian Poland, where the Uprising was mainly happening; he stayed in German Poland (historically known to Poles as Wielkopolska, or Greater Poland), where he was well received by members of the local Polish nobility.[23] He had a brief liaison with Konstancja Łubieńska at her family estate[23] in Śmiełów. Starting in March 1832, Mickiewicz stayed several months in Dresden, in Saxony,[23][25] where he wrote the third part of his poem Dziady.[25]

Paris émigré

On 31 July 1832 he arrived in Paris, accompanied by a close friend and fellow ex-Philomath, the future geologist and Chilean educator Ignacy Domeyko.[25] In Paris, Mickiewicz became active in many Polish émigré groups and published articles in Pielgrzym Polski (The Polish Pilgrim).[25] The fall of 1832 saw the publication, in Paris, of the third part of his Dziady (smuggled into partitioned Poland), as well as of The Books of the Polish People and of the Polish Pilgrimage, which Mickiewicz self-published.[25] During this time, he made acquaintances with the composer Frederic Chopin who would be one of Mickiewicz‘s closest friends in Paris. In 1834 he published another masterpiece, his epic poem Pan Tadeusz.[26]

Pan Tadeusz, his longest poetic work, marked the end of his most productive literary period.[26][27] Mickiewicz would create further notable works, such as Lausanne Lyrics, 1839–40) and Zdania i uwagi (Thoughts and Remarks, 1834–40), but neither would achieve the fame of his earlier works.[26] His relative literary silence, beginning in the mid-1830s, has been variously interpreted: he may have lost his talent; he may have chosen to focus on teaching and on political writing and organizing.[28]

On 22 July 1834, in Paris, he married Celina Szymanowska, daughter of composer and concert pianist Maria Agata Szymanowska.[26] They would have six children (two daughters, Maria and Helena; and four sons, Władysław, Aleksander, Jan and Józef).[26] Celina later became mentally ill, possibly with a major depressive disorder.[26] In December 1838, marital problems caused Mickiewicz to attempt suicide.[29] Celina would die on 5 March 1855.[26]

Mickiewicz and his family lived in relative poverty, their major source of income being occasional publication of his work – not a very profitable endeavor.[30] They received support from friends and patrons, but not enough to substantially change their situation.[30] Despite spending most of his remaining years in France, Mickiewicz would never receive French citizenship, nor any support from the French government.[30] By the late 1830s he was less active as a writer, and also less visible on the Polish émigré political scene.[26]

In 1838 Mickiewicz became professor of Latin literature at the Lausanne Academy, in Switzerland.[30] His lectures were well received, and in 1840 he was appointed to the newly established chair of Slavic languages and literatures at the Collège de France.[30][31] Leaving Lausanne, he was made an honorary Lausanne Academy professor.[30]

Mickiewicz would, however, hold the Collège de France post for little more than three years, his last lecture being delivered on 28 May 1844.[30] His lectures were popular, drawing many listeners in addition to enrolled students, and receiving reviews in the press.[30] Some would be remembered much later; his sixteenth lecture, on Slavic theater, "was to become a kind of gospel for Polish theater directors of the twentieth century."[32]

Over the years he became increasingly possessed by religious mysticism as he fell under the influence of the Polish philosopher Andrzej Towiański, whom he met in 1841.[30][33] His lectures became a medley of religion and politics, punctuated by controversial attacks on the Catholic Church, and thus brought him under censure by the French government.[30][33] The messianic element conflicted with Roman Catholic teachings, and some of his works were placed on the Church's list of prohibited books, though both Mickiewicz and Towiański regularly attended Catholic mass and encouraged their followers to do so.[33][34]

In 1846 Mickiewicz severed his ties with Towiański, following the rise of revolutionary sentiment in Europe, manifested in events such as the Kraków Uprising of February 1846.[35] Mickiewicz criticized Towiański's passivity and returned to the traditional Catholic Church.[35] In 1847 Mickiewicz befriended American journalist, critic and women's-rights advocate Margaret Fuller.[36] In March 1848 he was part of a Polish delegation received in audience by Pope Pius IX, whom he asked to support the enslaved nations and the French Revolution of 1848.[35] Soon after, in April 1848, he organized a military unit, the Mickiewicz Legion, to support the insurgents, hoping to liberate the Polish and other Slavic lands.[31][35] The unit never became large enough to be more than symbolic, and in the fall of 1848 Mickiewicz returned to Paris and became more active again on the political scene.[36]

In December 1848 he was offered a post at the Jagiellonian University in Austrian-ruled Kraków, but the offer was soon withdrawn after pressure from Austrian authorities.[36] In the winter of 1848–49, Polish composer Frédéric Chopin, in the final months of his own life, visited his ailing compatriot and soothed the poet's nerves with his piano music.[37] Over a dozen years earlier, Chopin had set two of Mickiewicz's poems to music (see Polish songs by Frédéric Chopin).[38]

Final years

In the winter of 1849 Mickiewicz founded a French-language newspaper, La Tribune des Peuples (The Peoples' Tribune), supported by a wealthy Polish émigré activist, Ksawery Branicki.[36] Mickiewicz wrote over 70 articles for the Tribune during its short existence: it came out between 15 March and 10 November 1849, when the authorities shut it down.[36][39] His articles supported democracy and socialism and many ideals of the French Revolution and of the Napoleonic era, though he held few illusions regarding the idealism of the House of Bonaparte.[36] He supported the restoration of the French Empire in 1851.[36] In April 1852 he lost his post at the Collège de France, which he had been allowed to keep up to that point (though without the right to lecture).[30][36] On 31 October 1852 he was hired as a librarian at the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal.[36][39] There he was visited by another Polish poet, Cyprian Norwid, who wrote of the meeting in his work Czarne kwiaty. Białe kwiaty; and there Mickiewicz's wife Celina died.[36]

Mickiewicz welcomed the Crimean War of 1853–1856, which he hoped would lead to a new European order including a restored independent Poland.[36] His last composition, a Latin ode Ad Napolionem III Caesarem Augustum Ode in Bomersundum captum, honored Napoleon III and celebrated the British-French victory over Russia at the Battle of Bomarsund[36] in Åland in August 1854. Polish émigrés associated with the Hôtel Lambert persuaded him to become active again in politics.[36][40] Soon after the Crimean War broke out (October 1853), the French government entrusted him with a diplomatic mission.[40] He left Paris on 11 September 1855, arriving in Constantinople, in the Ottoman Empire, on 22 September.[40] There, working with Michał Czajkowski (Sadyk Pasha), he began organizing Polish forces to fight under Ottoman command against Russia.[39][40] With his friend Armand Lévy he also set about organizing a Jewish legion.[39][40] He returned ill from a trip to a military camp to his apartment on Yenişehir Street in the Pera (now Beyoğlu) district of Constantinople and died on 26 November 1855.[40][41] Though Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński and others have speculated that political enemies might have poisoned Mickiewicz, there is no proof of this, and he probably contracted cholera, which claimed other lives there at the time.[39][40][42]

Mickiewicz's remains were transported to France, boarding ship on 31 December 1855, and were buried at Montmorency, Val-d'Oise, on 21 January 1861.[40] In 1890 they were disinterred, moved to Austrian Poland, and on 4 July entombed in the Crypts of the Bards of Kraków's Wawel Cathedral, a place of final repose for a number of persons important to Poland's political and cultural history.[40]

Works

Mickiewicz's childhood environment exerted a major influence on his literary work.[12][14] His early years were shaped by immersion in folklore[12] and by vivid memories, which he later reworked in his poems, of the ruins of Navahrudak Castle and of the triumphant entry and disastrous retreat of Polish and Napoleonic troops during Napoleon's 1812 invasion of Russia, when Mickiewicz was just a teenager.[14] The year 1812 also marked his father's death.[14] Later, the poet's personality and subsequent works were greatly influenced by his four years of living and studying in Vilnius.[17]

.jpg.webp)

His first poems, such as the 1818 Zima miejska (City Winter) and the 1819 Kartofla (Potato), were classical in style, influenced by Voltaire.[18][43] His Ballads and Romances and poetry anthologies published in 1822 (including the opening poem Romantyczność, Romanticism) and 1823 mark the start of romanticism in Poland.[17][18][44] Mickiewicz's influence popularized the use of folklore, folk literary forms, and historism in Polish romantic literature.[17] His exile to Moscow exposed him to a cosmopolitan environment, more international than provincial Vilnius and Kaunas in Lithuania.[22] This period saw a further evolution in his writing style, with Sonety (Sonnets, 1826) and Konrad Wallenrod (1828), both published in Russia.[22] The Sonety, mainly comprising his Crimean Sonnets, highlight the poet's ability and desire to write, and his longing for his homeland.[22]

One of his major works, Dziady (Forefathers' Eve), comprises several parts written over an extended period of time.[25][45] It began with publication of parts II and IV in 1823.[17] Miłosz remarks that it was "Mickiewicz's major theatrical achievement", a work which Mickiewicz saw as ongoing and to be continued in further parts.[24][45] Its title refers to the pagan ancestor commemoration that had been practiced by Slavic and Baltic peoples on All Souls' Day.[45] The year 1832 saw the publication of part III: much superior to the earlier parts, a "laboratory of innovative genres, styles and forms".[25] Part III was largely written over a few days; the "Great Improvisation" section, a "masterpiece of Polish poetry", is said to have been created during a single inspired night.[25] A long descriptive poem, Ustęp (Digression), accompanying part III and written sometime before it, sums up Mickiewicz's experiences in, and views on, Russia, portrays it as a huge prison, pities the oppressed Russian people, and wonders about their future.[46] Miłosz describes it as a "summation of Polish attitudes towards Russia in the nineteenth century" and notes that it inspired responses from Pushkin (The Bronze Horseman) and Joseph Conrad (Under Western Eyes).[46] The drama was first staged by Stanisław Wyspiański in 1901, becoming, in Miłosz's words, "a kind of national sacred play, occasionally forbidden by censorship because of its emotional impact upon the audience." The Polish government's 1968 closing down of a production of the play sparked the 1968 Polish political crisis.[32][47]

Mickiewicz's Konrad Wallenrod (1828), a narrative poem describing battles of the Christian order of Teutonic Knights against the pagans of Lithuania,[13] is a thinly veiled allusion to the long feud between Russia and Poland.[13][22] The plot involves the use of subterfuge against a stronger enemy, and the poem analyzes moral dilemmas faced by the Polish insurgents who would soon launch the November 1830 Uprising.[22] Controversial to an older generation of readers, Konrad Wallenrod was seen by the young as a call to arms and was praised as such by an Uprising leader, poet Ludwik Nabielak.[13][22] Miłosz describes Konrad Wallenrod (named for its protagonist) as "the most committed politically of all Mickiewczi's poems."[48] The point of the poem, though obvious to many, escaped the Russian censors, and the poem was allowed to be published, complete with its telling motto drawn from Machiavelli: "Dovete adunque sapere come sono due generazioni di combattere – bisogna essere volpe e leone." ("Ye shall know that there are two ways of fighting – you must be a fox and a lion.")[13][22][49] On a purely literary level, the poem was notable for incorporating traditional folk elements alongside stylistic innovations.[22]

Similarly noteworthy is Mickiewicz's earlier and longer 1823 poem, Grażyna, depicting the exploits of a Lithuanian chieftainess against the Teutonic Knights.[50][51] Miłosz writes that Grażyna "combines a metallic beat of lines and syntactical rigor with a plot and motifs dear to the Romantics."[50] It is said by Christien Ostrowski to have inspired Emilia Plater, a military heroine of the November 1830 Uprising.[52] A similar message informs Mickiewicz's "Oda do młodości" ("Ode to Youth").[17]

Mickiewicz's Crimean Sonnets (1825–26) and poems that he would later write in Rome and Lausanne, Miłosz notes, have been "justly ranked among the highest achievements in Polish [lyric poetry]."[49] His 1830 travels in Italy likely inspired him to consider religious matters, and produced some of his best religiously themed works, such as Arcymistrz (The Grand Master) and Do Marceliny Łempickiej (To Marcelina Łempicka).[23] He was an authority to the young insurgents of 1830–31, who expected him to participate in the fighting (the poet Maurycy Gosławski wrote a dedicated poem urging him to do so).[23] Yet it is likely that Mickiewicz was no longer as idealistic and supportive of military action as he had been a few years earlier, and his new works such as Do Matki Polki (To a Polish Mother, 1830), while still patriotic, also began to reflect on the tragedy of resistance.[23] His meetings with refugees and escaping insurgents around 1831 resulted in works such as Reduta Ordona (Ordon's Redoubt), Nocleg (Night Bivouac) and Śmierć pułkownika (Death of the Colonel).[23] Wyka notes the irony that some of the most important literary works about the 1830 Uprising were written by Mickiewicz, who never took part in a battle or even saw a battlefield.[23]

His Księgi narodu polskiego i pielgrzymstwa polskiego (Books of the Polish Nation and the Polish Pilgrimage, 1832) opens with a historical-philosophical discussion of the history of humankind in which Mickiewicz argues that history is the history of now-unrealized freedom that awaits many oppressed nations in the future.[25][26] It is followed by a longer "moral catechism" aimed at Polish émigrés.[26] The book sets out a messianist metaphor of Poland as the "Christ of nations".[53] Described by Wyka as a propaganda piece, it was relatively simple, using biblical metaphors and the like to reach less-discriminating readers.[26] It became popular not only among Poles but, in translations, among some other peoples, primarily those which lacked their own sovereign states.[26][27] The Books were influential in framing Mickiewicz's image among many not as that of a poet and author but as that of ideologue of freedom.[26]

Pan Tadeusz (Sir Thaddeus, published 1834), another of his masterpieces, is an epic poem that draws a picture of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on the eve of Napoleon's 1812 invasion of Russia.[26][27] It is written entirely in thirteen-syllable couplets.[27] Originally intended as an apolitical idyll, it became, as Miłosz writes, "something unique in world literature, and the problem of how to classify it has remained the crux of a constant quarrel among scholars"; it "has been called 'the last epos' in world literature".[54] Pan Tadeusz was not highly regarded by contemporaries, nor by Mickiewicz himself, but in time it won acclaim as "the highest achievement in all Polish literature."[28]

The occasional poems that Mickiewicz wrote in his final decades have been described as "exquisite, gnomic, extremely short and concise". His Lausanne Lyrics, (1839–40) are, writes Miłosz, "untranslatable masterpieces of metaphysical meditation. In Polish literature, they are examples of that pure poetry that verges on silence."[31]

In the 1830s (as early as 1830; as late as 1837) he worked on a futurist or science-fiction work, A History of the Future. (Historia przyszłości, or L’histoire d’avenir)[25] It predicted inventions similar to radio and television, and interplanetary communication using balloons.[25] Written partially in French, it was never completed and was partly destroyed by the author.[25] Other French-language works by Mickiewicz include the dramas Konfederaci barscy (The Bar Confederates) and Jacques Jasiński, ous les deux Polognes (Jacques Jasiński, or the Two Polands).[26] These would not achieve much recognition, and would not be published till 1866.[26]

Lithuanian language

Adam Mickiewicz did not write any poems in Lithuanian. However, it is known that Mickiewicz did have some understanding of the Lithuanian language, although some Polish commentators describe it as limited.[55][56][57]

In the poem Grażyna, Mickiewicz quoted one sentence from Kristijonas Donelaitis' Lithuanian-language poem Metai.[58] In Pan Tadeusz, there is a un-Polonized Lithuanian name Baublys.[59] Furthermore, due to Mickiewicz's position as lecturer on Lithuanian folklore and mythology in Collège de France, it can be inferred that he must have known the language sufficiently to lecture about it.[60] It is known that Adam Mickiewicz often sang Lithuanian folk songs with the Samogitian Ludmilew Korylski.[61] For example, in the early 1850s when in Paris, Mickiewicz interrupted a Lithuanian folk song sung by Ludmilew Korylski, commenting that he was singing it wrong and hence wrote down on a piece of paper how to sing the song correctly.[61] On the piece of paper, there are fragments of three different Lithuanian folk songs (Ejk Tatuszeli i bytiu darża, Atjo żałnieros par łauka, Ej warneli, jod warneli isz),[62] which are the sole, as of now, known Lithuanian writings by Adam Mickiewicz.[63] The folk songs are known to have been sung in Darbėnai.[64]

Legacy

A prime figure of the Polish Romantic period, Mickiewicz is counted as one of Poland's's Three Bards (the others being Zygmunt Krasiński and Juliusz Słowacki) and the greatest poet in all Polish literature.[2][3][4] Mickiewicz has long been regarded as Poland's national poet[65][66] and is a revered figure in Lithuania.[67] He is also considered one of the greatest Slavic[5] and European[6] poets. He has been described as a "Slavic bard".[7] He was a leading Romantic dramatist[8] and has been compared in Poland and in Europe with Byron and Goethe.[7][8]

Mickiewicz's importance extends beyond literature to the broader spheres of culture and politics; Wyka writes that he was a "singer and epic poet of the Polish people and a pilgrim for the freedom of nations."[40] Scholars have used the expression "cult of Mickiewicz" to describe the reverence in which he is held as a "national prophet."[40][68][69] On hearing of Mickiewicz's death, his fellow bard Krasiński wrote:

For men of my generation, he was milk and honey, gall and life's blood: we all descend from him. He carried us off on the surging billow of his inspiration and cast us into the world.[40][70]

Edward Henry Lewinski Corwin described Mickiewicz's works as Promethean, as "reaching more Polish hearts" than the other Polish Bards, and affirmed Danish critic Georg Brandes' assessment of Mickiewicz's works as "healthier" than those of Byron, Shakespeare, Homer, and Goethe.[71] Koropeckyi writes that Mickiewicz has "informed the foundations of [many] parties and ideologies" in Poland from the 19th century to this day, "down to the rappers in Poland's post-socialist blocks, who can somehow still declare that 'if Mickiewicz was alive today, he'd be a good rapper.'"[72] While Mickiewicz's popularity has endured two centuries in Poland, he is less well known abroad, but in the 19th century he had won substantial international fame among "people that dared resist the brutal might of reactionary empires."[72]

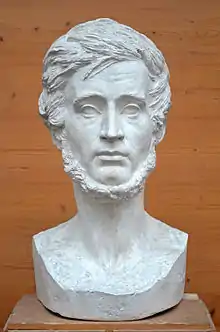

Mickiewicz has been written about or had works dedicated to him by many authors in Poland (Asnyk, Gałczyński, Iwaszkiewicz, Jastrun, Kasprowicz, Lechoń, Konopnicka, Teofil Lenartowicz, Norwid, Przyboś, Różewicz, Słonimski, Słowacki, Staff, Tetmajer, Tuwim, Ujejski, Wierzyński, Zaleski and others) and by authors outside Poland (Bryusov, Goethe, Pushkin, Uhland, Vrchlický and others).[40] He has been a character in works of fiction, including a large body of dramatized biographies, e.g., in 1900, Stanisław Wyspiański's Legion.[40] He has also been a subject of many paintings, by Eugène Delacroix, Józef Oleszkiewicz, Aleksander Orłowski, Wojciech Stattler and Walenty Wańkowicz.[73] Monuments and other tributes (streets and schools named for him) abound in Poland and Lithuania, and in other former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth: Ukraine and Belarus.[40][72] He has also been the subject of many statues and busts by Antoine Bourdelle, David d'Angers, Antoni Kurzawa, Władysław Oleszczyński, Zbigniew Pronaszko, Teodor Rygier, Wacław Szymanowski and Jakub Tatarkiewicz.[73] In 1898, the 100th anniversary of his birth, a towering statue by Cyprian Godebski was erected in Warsaw. Its base carries the inscription, "To the Poet from the People".[74] In 1955, the 100th anniversary of his death, the University of Poznań adopted him as its official patron.[40]

Much has been written about Mickiewicz, though the vast majority of this scholarly and popular literature is available only in Polish. Works devoted to him, according to Koropeckyi, author of a 2008 English biography, "could fill a good shelf or two".[72] Koropeckyi notes that, apart from some specialist literature, only five book-length biographies of Mickiewicz have been published in English.[72] He also writes that, though many of Mickiewicz's works have been reprinted numerous times, no language has a "definitive critical edition of his works."[72]

Museums

_portrait.jpg.webp)

A number of museums in Europe are dedicated to Mickiewicz:

- Warsaw has an Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature.[40]

- His house in Navahrudak is now a museum (Adam Mickiewicz Museum, Navahrudak).[75]

- There is a Mickievičiaus Memorialinis Būtas-Muziejus Museum of Adam Mickiewicz in Vilnius.

- The House of Perkūnas in Kaunas where the school Mickiewicz attended used to be located has a museum devoted to him and his work.

- The house where he lived and died in Constantinople (Adam Mickiewicz Museum, Istanbul).[40]

- There is a Musée Adam Mickiewicz in Paris, France.[76]

Ethnicity

Adam Mickiewicz is known as a Polish poet,[77][78][79][80][81] Polish-Lithuanian,[82][83][84][85] Lithuanian,[86][87][88][89][90][91] or Belarusian.[92] The Cambridge History of Russia describes him as Polish but sees his ethnic origins as "Lithuanian-Belarusian (and perhaps Jewish)."[93]

Some sources assert that Mickiewicz's mother was descended from a converted, Frankist Jewish family.[94][95][96] Others view this as improbable.[39][97][98][99] Polish historian Kazimierz Wyka, in his biographic entry in Polski Słownik Biograficzny (1975) wrote that this hypothesis, based on the fact that his mother's maiden name, Majewska, was popular among Frankist Jews, but has not been proven.[14] Wyka states that the poet's mother was the daughter of a noble (szlachta) family of Starykoń coat of arms, living on an estate at Czombrów in Nowogródek Voivodeship (Navahrudak Voivodeship).[14] According to the Belarusian historian Rybczonek, Mickiewicz's mother had Tatar (Lipka Tatars) roots.[100]

Virgil Krapauskas noted that "Lithuanians like to prove that Adam Mickiewicz was Lithuanian"[101] while Tomas Venclova described this attitude as "the story of Mickiewicz’s appropriation by Lithuanian culture".[9] For example, the Lithuanian scholar of literature Juozapas Girdzijauskas writes that Mickiewicz's family was descended from an old Lithuanian noble family (Rimvydas) with origins predating Lithuania's Christianization,[102] but the Lithuanian nobility in Mickiewicz's time was heavily Polonized and spoke Polish.[9] Mickiewicz had been brought up in the culture of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a multicultural state that had encompassed most of what today are the separate countries of Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. To Mickiewicz, a splitting of that multicultural state into separate entities – due to trends such as Lithuanian National Revival – was undesirable,[9] if not outright unthinkable.[77] According to Romanucci-Ross, while Mickiewicz called himself a Litvin ("Lithuanian"), in his time the idea of a separate "Lithuanian identity", apart from a "Polish" one, did not exist.[81] This multicultural aspect is evident in his works: his most famous poetic work, Pan Tadeusz, begins with the Polish-language invocation, "Oh Lithuania, my homeland, thou art like health ..." ("Litwo! Ojczyzno moja! ty jesteś jak zdrowie ..."). It is generally accepted, however, that Mickiewicz, when referring to Lithuania, meant a historical region rather than a linguistic and cultural entity, and he often applied the term "Lithuanian" to the Slavic inhabitants of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[9]

Selected works

- Oda do młodości (Ode to Youth), 1820

- Ballady i romanse (Ballads and Romances), 1822

- Grażyna, 1823

- Sonety krymskie (The Crimean Sonnets), 1826

- Konrad Wallenrod, 1828

- Księgi narodu polskiego i pielgrzymstwa polskiego (The Books of the Polish People and of the Polish Pilgrimage), 1832

- Pan Tadeusz (Sir Thaddeus, Mr. Thaddeus), 1834

- Lausanne Lyrics, 1839–40

- Dziady (Forefathers' Eve), four parts, published from 1822 to after the author's death

- L'histoire d'avenir (A History of the Future), an unpublished French-language science-fiction novel

See also

- List of things named after Adam Mickiewicz

- List of Poles

- Polish literature

- All pages with titles containing Mickiewicz

Notes

a ^ Czesław Miłosz and Kazimierz Wyka each note that Adam Mickiewicz's exact birthplace cannot be ascertained due to conflicting records and missing documentation.[12][14]

References

- "Poland's Famous Poets". Polish-dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- S. Treugutt: Mickiewicz – domowy i daleki. in: A. Mickiewicz: Dzieła I. Warszawa 1998, p. 7

- E. Zarych: Posłowie. in: A. Mickiewicz: Ballady i romanse. Kraków 2001, p. 76

- Roman Koropeckyj (2010). "Adam Mickiewicz as a Polish National Icon". In Marcel Cornis-Pope; John Neubauer (eds.). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Eastern Europe. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 39. ISBN 978-90-272-3458-2.

- Krystyna Pomorska; Henryk Baran (1992). Jakobsonian poetics and Slavic narrative: from Pushkin to Solzhenitsyn. Duke University Press. pp. 239–. ISBN 978-0-8223-1233-8.

- Andrzej Wójcik; Marek Englender (1980). Budowniczowie gwiazd. Krajowa Agencja Wydawn. pp. 19–10.

- Zofia Mitosek (1999). Adam Mickiewicz w oczach Francuzów [Adam Mickiewicz to French Eyes]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. p. 12. ISBN 978-83-01-12639-1.

- T. Macios, Posłowie (Afterword) to Adam Mickiewicz, Dziady, Kraków, 2004, pp. 239–40.

- Venclova, Tomas. "Native Realm Revisited: Mickiewicz's Lithuania and Mickiewicz in Lithuania". Lituanus Volume 53, No 3 – Fall 2007. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

This semantic confusion was amplified by the fact that the Nowogródek region, although inhabited mainly by Belarusian speakers, was for several centuries considered part and parcel of Lithuania Propria—Lithuania in the narrow sense; as different from the 'Ruthenian' regions of the Grand Duchy.

- "Yad Vashem Studies". Yad Washem Studies on the European Jewish Catastrophe and Resistance. Wallstein Verlag: 38. 2007. ISSN 0084-3296.

- Vytautas Kubilius (1998). Adomas Mickevičius: poetas ir Lietuva. Lietuvos rašytojų sąjungos leidykla. p. 49. ISBN 9986-39-082-6.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Roman Robert Koropeckyj (2008). Adam Mickiewicz: The Life of a Romantic. Cornell University Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-0-8014-4471-5.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 694.

- Kenneth R. Wulff (1992). Education in Poland: Past, Present, and Future. University Press of America. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8191-8615-7.

- "Adam Mickiewicz - informacje o autorze, biografia". lekcjapolskiego.pl. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 695.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- (in Russian) Adam Mickiewitch, Poems, Moscow, 1979, pp. 122, 340.

- (in Russian) David Tukhmanov Archived 10 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 696.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 697.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 698.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 699.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Twórczość. RSW "Prasa-Książa-Ruch". 1998. p. 80.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 700.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 701.

- Robert E. Alvis (2005). Religion and the rise of nationalism: a profile of an East-Central European city. Syracuse University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8156-3081-4.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 702.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 703.

- Zdzisław Jachimecki, "Chopin, Fryderyk Franciszek," Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. III, Kraków, Polska Akademia Umiejętności, 1937, p. 424.

- Zdzisław Jachimecki, "Chopin, Fryderyk Franciszek," Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. III, Kraków, Polska Akademia Umiejętności, 1937, p. 423.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 704.

- Muzeum Adama Mickiewicza w Stambule (przewodnik). Ministerstwo Kultury i Turystyki Republiki Turcji – Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, 26 November 2005.

- Christopher John Murray (2004). Encyclopedia of the romantic era, 1760–1850, Volume 2. Taylor & Francis. p. 742. ISBN 978-1-57958-422-1. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. pp. 214–217. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Kinga Olszewska (2007). Wanderers across language: exile in Irish and Polish literature of the twentieth century. MHRA. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-905981-08-3.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- The Westminster Review. J.M. Mason. 1879. p. 378.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Mieczysław Jackiewicz (1999). Literatura litewska w Polsce w XIX i XX wieku. Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego. p. 21. ISBN 978-83-912643-4-8.

- "Svetainė išjungta – Serveriai.lt". Znadwiliiwilno.lt. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- Jerzy Surwiło (1993). Skaičių šalis : matematikos vadovėlis II klasei. Wydawn. "Magazyn Wileński. p. 28. ISBN 978-5-430-01467-4.

- Digimas, A. (1984). Ar Adomas Mickevičius mokėjo lietuviškai? [Did Adam Mickiewicz know the Lithuanian language?] (Videotape) (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos Kino Studija. 4:30-4:36 minutes in. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Digimas, A. (1984). Ar Adomas Mickevičius mokėjo lietuviškai? [Did Adam Mickiewicz know the Lithuanian language?] (Videotape) (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos Kino Studija. 5:58-6:13 minutes in. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Digimas, A. (1984). Ar Adomas Mickevičius mokėjo lietuviškai? [Did Adam Mickiewicz know the Lithuanian language?] (Videotape) (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos Kino Studija. 4:44-4:54 minutes in. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Digimas, A. (1984). Ar Adomas Mickevičius mokėjo lietuviškai? [Did Adam Mickiewicz know the Lithuanian language?] (Videotape) (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos Kino Studija. 6:26-7:05 minutes in. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Adomas Mickevičius - Lietuviškų dainų fragmentai" [Adomas Mickevičius and fragments of Lithuanian songs]. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- "About the fragments of Lithuanian songs, written down by Adomas Mickevičius". Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- Digimas, A. (1984). Ar Adomas Mickevičius mokėjo lietuviškai? [Did Adam Mickiewicz know the Lithuanian language?] (Videotape) (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos Kino Studija. 7:00-7:06 minutes in. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Gardner, Monica Mary (1911). Adam Mickiewicz: the national poet of Poland. New York: J.M. Dent & Sons. OCLC 464724636. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- Krzyżanowski, Julian, ed. (1986). Literatura polska: przewodnik encyklopedyczny, Volume 1: A–M. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 663–665. ISBN 83-01-05368-2.

- Dalia Grybauskaitė (2008). "Address by H.E. Dalia Grybauskaitė, President of the Republic of Lithuania, at the Celebration of the 91st Anniversary of Polish Independence Day". President of the Republic of Lithuania. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- Andrew Wachtel (2006). Remaining Relevant After Communism: The Role of the Writer in Eastern Europe. University of Chicago Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-226-86766-3.

- Jerzy Peterkiewicz (1970). Polish prose and verse: a selection with an introductory essay. University of London, Athlone Press. p. xlvii. ISBN 978-0-485-17502-8.

- Adam Mickiewicz; Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America (1944). Poems by Adam Mickiewicz. The Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America. p. 63. ISBN 9780940962248.

- Edward Henry Lewinski Corwin (1917). The Political History of Poland. Polish Book Importing Co. p. 449.

He feels for millions and is pleading before God for their happiness and spiritual perfection.

- Roman Koropeckyi (2008). Adam Mickiewicz. Cornell University Press. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-0-8014-4471-5.

- Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 705.

- Jabłoński, Rafał (2002). Warsaw and surroundings. Warsaw: Festina. p. 103. OCLC 680169225.

The Adam Mickiewicz Monument was unveiled in 1898 to mark the 100th anniversary of the great romantic poet's birth. The inscription on the base reads: "To the Poet from the Nation"

- "Muzeum Adama Mickiewicza w Nowogródku". Ebialorus.pl. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- "Musee Adam Mickiewicz". En.parisinfo.com. 24 March 2000. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- Kevin O'Connor (2006). Culture and customs of the Baltic states. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1.

- Manfred Kridl (1951). Adam Mickiewicz, poet of Poland: a symposium. Columbia University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780231901802.

- Christopher John Murray (2004). Encyclopedia of the romantic era, 1760–1850. Taylor & Francis. p. 739. ISBN 978-1-57958-422-1.

- Olive Classe (2000). Encyclopedia of literary translation into English: M-Z. Taylor & Francis. p. 947. ISBN 978-1-884964-36-7.

- Lola Romanucci-Ross; George A. De Vos; Takeyuki Tsuda (2006). Ethnic Identity: Problems And Prospects for the Twenty-first Century. Rowman Altamira. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-7591-0973-5.

- William Richard Morfill, Poland, 1893, p. 300.

- Karin Ikas; Gerhard Wagner (2008). Communicating in the Third Space. Routledge. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-203-89116-2.

- "United Nations in Belarus – Culture". United Nations. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- Studia Polonijne, Tomy 22–23, Towarzystwo Naukowe Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego, 2001, page 266

- Paneth, Philip (1939). Is Poland Lost?. London: Nicholson and Watson. p. 41.

- Mills, Clark; Landsbergis, Algirdas (1962). The Green Oak. New York: Theo. Gaus' Sons. p. 15.

- Morfill, W.R. (1893). Poland. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 300.

- Boswell, A. Bruce (1919). Poland and the Poles. London: Methuen & Co. p. 217.

- Harrison, E.J. (1922). Lithuania, Past & Present. London: Gresham Press. p. 165.

- Bjornson, B. (1941). Poet Lore World Literature and the Drama. Boston: Bruce Humphries. p. 327.

- Gliński, Mikołaj. "The White-Red-White Banner of Polish-Belarusian Literature". Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Maureen Perrie; D. C. B. Lieven; Ronald Grigor Suny (2006). The Cambridge History of Russia: Imperial Russia, 1689–1917. Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-521-81529-1. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Balaban, Meir, The History of the Frank Movement, 2 vols., 1934–35, pp. 254–259.

- "Mickiewicz's mother, descended from a converted Frankist family": "Mickiewicz, Adam," Encyclopaedia Judaica. "Mickiewicz's Frankist origins were well-known to the Warsaw Jewish community as early as 1838 (according to evidence in the AZDJ of that year, p. 362). "The parents of the poet's wife also came from Frankist families": "Frank, Jacob, and the Frankists," Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- Magdalena Opalski; Baṛtal, Israel (1992). Poles and Jews: A Failed Brotherhood. UPNE. pp. 119–21. ISBN 978-0-87451-602-9.

the Frankist background of the poet's mother

- Wiktor Weintraub (1954). The poetry of Adam Mickiewicz. Mouton. p. 11.

Her (Barbara Mickiewicz) maiden name was Majewska. In old Lithuania, every baptised Jew became ennobled, and there were Majewskis of Jewish origin. That must have been the reason for the rumours, repeated by some of the poet's contemporaries, that Mickiewicz's mother was a Jewess by origin. However, genealogical research makes such an assumption rather improbable

- Czesław Milosz (2000). The Land of Ulro. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-374-51937-7.

The mother's low social status—her father was a land steward—argues against a Frankist origin. The Frankists were usually of the nobility and therefore socially superior to the common gentry.

- (in Polish) Paweł Goźliński, "Rzym koło Nowogródka" Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine (Rome near Nowogródek), interview with historian Tomasz Łubieński, editor-in-chief of Nowe Ksiąźki, Gazeta Wyborcza, 16 October 1998.

- Rybczonek, S., "Przodkowie Adama Mickiewicza po kądzieli" ("Adam Mickiewicz's Ancestors on the Distaff Side"), Blok-Notes Muzeum Literatury im. Adama Mickiewicza, 1999, no. 12/13.

- Krapauskas, Virgil (1 September 1998). "Political change in Poland and Lithuania: The impact on Polish-Lithuanian ethnic relations as reflected in Lithuanian-language publications in Poland (1945–1991)". Journal of Baltic Studies. 29 (3): 261–278. doi:10.1080/01629779800000111. ISSN 0162-9778. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Adomas Mickevičius (Adam Mickiewicz)". Lithuanian Classic Literature Anthology (UNESCO "Publica" series). Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Adam Mickiewicz". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Adam Mickiewicz". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

- Roman Koropeckyj (2008). Adam Mickiewicz: The Life of a Romantic. Cornell UP. ISBN 978-0-8014-4471-5.

- Jadwiga Maurer (1996). "Z matki obcej–": szkice o powiązaniach Mickiewicza ze światem Żydów (Of a Foreign Mother ... Sketches about Adam Mickiewicz's Ties to the Jewish World). Fabuss. ISBN 978-83-902649-1-2.

External links

- Works by Adam Mickiewicz in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Adam Mickiewicz at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Adam Mickiewicz at Internet Archive

- Works by Adam Mickiewicz at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Four Sonnets translated by Leo Yankevich

- Translation of "the Akkerman Steppe"

- Sonnets from the Crimea (Sonety krymskie) translated by Edna W. Underwood

- Adam Mickiewicz Selected Poems (in English)

- Mickiewicz's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- Polish Literature in English Translation: Mickiewicz

- Adam Mickiewicz Museum Istanbul (in Turkish)

- Polish poetry in English (includes a few poems by Mickiewicz)

- Adam Mickiewicz at Culture.pl

- Translating Mickiewicz: Poland's International Man of Mystery at Culture.pl

- Adam Mickiewicz Slept Here! A Worldwide Guide to Museums of Poland’s Poetic Hero at Culture.pl

- Adam Mickiewicz at poezja.org (polish)