Prehistoric art

In the history of art, prehistoric art is all art produced in preliterate, prehistorical cultures beginning somewhere in very late geological history, and generally continuing until that culture either develops writing or other methods of record-keeping, or makes significant contact with another culture that has, and that makes some record of major historical events. At this point ancient art begins, for the older literate cultures. The end-date for what is covered by the term thus varies greatly between different parts of the world.[lower-alpha 1]

| History of art |

|---|

The earliest human artifacts showing evidence of workmanship with an artistic purpose are the subject of some debate. It is clear that such workmanship existed 40,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic era, although it is quite possible that it began earlier. In September 2018, scientists reported the discovery of the earliest known drawing by Homo sapiens, which is estimated to be 73,000 years old, much earlier than the 43,000 years old artifacts understood to be the earliest known modern human drawings found previously.[2]

Engraved shells created by Homo erectus dating as far back as 500,000 years ago[3] have been found, although experts disagree on whether these engravings can be properly classified as 'art'.[4] From the Upper Paleolithic through to the Mesolithic, cave paintings and portable art such as figurines and beads predominated, with decorative figured workings also seen on some utilitarian objects. In the Neolithic evidence of early pottery appeared, as did sculpture and the construction of megaliths. Early rock art also first appeared during this period. The advent of metalworking in the Bronze Age brought additional media available for use in making art, an increase in stylistic diversity, and the creation of objects that did not have any obvious function other than art. It also saw the development in some areas of artisans, a class of people specializing in the production of art, as well as early writing systems. By the Iron Age, civilizations with writing had arisen from Ancient Egypt to Ancient China.

Many indigenous peoples from around the world continued to produce artistic works distinctive to their geographic area and culture, until exploration and commerce brought record-keeping methods to them. Some cultures, notably the Maya civilization, independently developed writing during the time they flourished, which was then later lost. These cultures may be classified as prehistoric, especially if their writing systems have not been deciphered.

Paleolithic era

Lower and Middle Paleolithic

.jpg.webp)

The earliest undisputed art originated with the Homo sapiens Aurignacian archaeological culture in the Upper Paleolithic. However, there is some evidence that the preference for the aesthetic emerged in the Middle Paleolithic, from 100,000 to 50,000 years ago. Some archaeologists have interpreted certain Middle Paleolithic artifacts as early examples of artistic expression.[6][7] The symmetry of artifacts, evidence of attention to the detail of tool shape, has led some investigators to conceive of Acheulean hand axes and especially laurel points as having been produced with a degree of artistic expression.

Similarly, a zigzag engraving supposedly made with a shark tooth on a freshwater Pseudodon shell DUB1006-fL around 500,000 years ago (i.e. well into the Lower Paleolithic), associated with Homo erectus, could be the earliest evidence of artistic activity, but the actual intent behind this geometric ornament is not known.[5]

There are other claims of Middle Paleolithic sculpture, dubbed the "Venus of Tan-Tan" (before 300 kya)[8] and the "Venus of Berekhat Ram" (250 kya). In 2002 in Blombos cave, situated in South Africa, stones were discovered engraved with grid or cross-hatch patterns, dated to some 70,000 years ago. This suggested to some researchers that early Homo sapiens were capable of abstraction and production of abstract art or symbolic art. Several archaeologists including Richard Klein are hesitant to accept the Blombos caves as the first example of actual art.

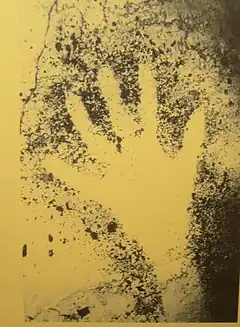

In September 2018 the discovery in South Africa of the earliest known drawing by Homo sapiens was announced, which is estimated to be 73,000 years old, much earlier than the 43,000 years old artifacts understood to be the earliest known modern human drawings found previously.[2] The drawing shows a crosshatched pattern made up of nine fine lines. The sudden termination of all of the lines on the fragment edges indicate that the pattern originally extended over a larger surface.[9] It is also estimated that the pattern was most likely more complex and structured in its entirety than shown on the discovered area. Initially, when this drawing was found, there was much debate. To prove that this drawing was created by Homo Sapiens, French team members who specialized in chemical analysis of pigments, reproduced the same lines using a variety of techniques.[10] They concluded that the lines making up the drawing were intentional and were most likely made with ocher. This discovery adds further dimensions to understanding the behavior and cognition of early homo sapiens.

Neanderthals may have made art. Painted designs in the caves of La Pasiega (Cantabria), a hand stencil in Maltravieso (Extremadura), and red-painted speleothems in Ardales (Andalusia) are dated to 64,800 years ago, predating by at least 20,000 years the arrival of modern humans in Europe.[11][12] In July 2021, scientists reported the discovery of a bone carving, one of the world's oldest works of art, made by Neanderthals about 51,000 years ago.[13][14]

Upper Paleolithic

- (Right) Giant deer bone of Einhornhöhle, Germany, c. 49,000 BC[17][18]

In November 2018, scientists reported the discovery of the oldest known figurative art painting, over 40,000 (perhaps as old as 52,000) years old, of an unknown animal, in the cave of Lubang Jeriji Saléh on the Indonesian island of Borneo, while in 2020 a Megaloceros bone was found in the Harz mountains in Germany, on which specimens of Homo neanderthalensis carved ornaments 51,000 years ago.[15][16][17][18]

The oldest undisputed works of figurative art were found in the Schwäbische Alb, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The earliest of these, the Venus figurine known as the Venus of Hohle Fels and the Lion-man figurine, date to some 40,000 years ago.

Further depictional art from the Upper Palaeolithic period (broadly 40,000 to 10,000 years ago) includes cave painting (e.g., those at Chauvet, Altamira, Pech Merle, Arcy-sur-Cure and Lascaux) and portable art: Venus figurines like the Venus of Willendorf, as well as animal carvings like the Swimming Reindeer, Wolverine pendant of Les Eyzies, and several of the objects known as bâtons de commandement.

Paintings in Pettakere cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi are up to 40,000 years old, a similar date to the oldest European cave art, which may suggest an older common origin for this type of art, perhaps in Africa.[19]

Monumental open-air art in Europe from this period includes the rock-art at Côa Valley and Mazouco in Portugal, Domingo García and Siega Verde in Spain, and Rocher gravé de Fornols in France.

A cave at Turobong in South Korea containing human remains has been found to contain carved deer bones and depictions of deer that may be as much as 40,000 years old.[20] Petroglyphs of deer or reindeer found at Sokchang-ri may also date to the Upper Paleolithic. Potsherds in a style reminiscent of early Japanese work have been found at Kosan-ri on Jeju island, which, due to lower sea levels at the time, would have been accessible from Japan.[21]

The oldest petroglyphs are dated to approximately the Mesolithic and late Upper Paleolithic boundary, about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. The earliest undisputed African rock art dates back about 10,000 years. The first naturalistic paintings of humans found in Africa date back about 8,000 years apparently originating in the Nile River valley, spread as far west as Mali about 10,000 years ago. Noted sites containing early art include Tassili n'Ajjer in southern Algeria, Tadrart Acacus in Libya (A Unesco World Heritage site), and the Tibesti Mountains in northern Chad.[22] Rock carvings at the Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa have been dated to this age.[23] Contentious dates as far back as 29,000 years have been obtained at a site in Tanzania. A site at the Apollo 11 Cave complex in Namibia has been dated to 27,000 years.

Göbekli Tepe in Turkey has circles of massive T-shaped stone pillars dating back to the 10th–8th millennium BCE; the world's oldest known megaliths. Many of the pillars are decorated with abstract, enigmatic pictograms and carved animal reliefs.

Asia

Asia was the cradle for several significant civilizations, most notably those of China and South Asia. The prehistory of eastern Asia is especially interesting, as the relatively early introduction of writing and historical record-keeping in China has a notable impact on the immediately surrounding cultures and geographic areas. Little of the very rich traditions of the art of Mesopotamia counts as prehistoric, as writing was introduced so early there, but neighbouring cultures such as Urartu, Luristan and Persia had significant and complex artistic traditions.

Indian sub-continent

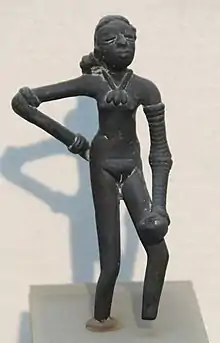

The earliest Indian paintings were the rock paintings of prehistoric times, the petroglyphs as found in places like the Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka, and some of them are dated to c. 8,000 BC.[24][25][26][27][28] The Indus Valley civilization produced fine small stamp seals and sculptures, and may have been literate, but after its collapse there are relatively few artistic remains until the literate period, probably as perishable materials were used.

Azerbaijan

The Gobustan National Park reserve located at the south-east of the Greater Caucasus Mountains in Azerbaijan, 60 km away from Baku date back more than 12 thousand years ago. The reserve has more than 6,000 rock carvings depicting mostly hunting scenes, human and animal figures. There are also longship illustrations similar to Viking ships. Gobustan is also characterized by its natural musical stone called Gavaldash (tambourine stone).[29][30][31][32]

China

.jpg.webp)

Prehistoric artwork such as painted pottery in Neolithic China can be traced back to the Yangshao culture and Longshan culture of the Yellow River valley. During China's Bronze Age, Chinese of the ancient Shang Dynasty and Zhou Dynasty produced multitudes of Chinese ritual bronzes, which are elaborate versions of ordinary vessels and other objects used in rituals of ancestor veneration, decorated with taotie motifs and by the late Shang Chinese bronze inscriptions. Discoveries in 1987 in Sanxingdui in central China revealed a previously unknown pre-literate Bronze Age culture whose artefacts included spectacular very large bronze figures (example left), and which appeared culturally very different from the contemporary late Shang, which has always formed part of the account of the continuous tradition of Chinese culture.

Japan

According to archeological evidence, the Jōmon people in ancient Japan were among the first to develop pottery, dated from the 11th millennium BCE. With growing sophistication, the Jōmon created patterns by impressing the wet clay with braided or unbraided cord and sticks.

Korea

The earliest examples of Korean art consist of Stone Age works dating from 3000 BCE. These mainly consist of votive sculptures, although petroglyphs have also been recently rediscovered. Rock arts, elaborate stone tools, and potteries were also prevalent.

This early period was followed by the art styles of various Korean kingdoms and dynasties. In these periods, artists often adopted Chinese style in their artworks. However, Koreans not only adopted but also modified Chinese culture with a native preference for simple elegance, purity of nature and spontaneity. This filtering of Chinese styles later influenced Japanese artistic traditions, due to cultural and geographical circumstances.

The prehistory of Korea ends with the founding of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, which are documented in the Samguk Sagi, a 12th-century CE text written in Classical Chinese (the written language of the literati in traditional Korea), as beginning in the 1st century BCE; some mention of earlier history is also made in Chinese texts, like the 3rd-century CE Sanguo Zhi.

Jeulmun period

Clearer evidence of culture emerges in the late Neolithic, known in Korea as the Jeulmun pottery period, with pottery similar to that found in the adjacent regions of China, decorated with Z-shaped patterns. The earliest Neolithic sites with pottery remains, for example Osan-ri, date to 6000–4500 BCE.[21] This pottery is characterized by comb patterning, with the pot frequently having a pointed base. Ornaments from this time include masks made of shell, with notable finds at Tongsam-dong, Osan-ri, and Sinam-ri. Hand-shaped clay figurines have been found at Nongpo-dong.[33]

Mumun period

During the Mumun pottery period, roughly between 1500 BCE and 300 BCE, agriculture expanded, and evidence of larger-scale political structures became apparent, as villages grew and some burials became more elaborate. Megalithic tombs and dolmens throughout Korea date to this time. The pottery of the time is in a distinctive undecorated style. Many of these changes in style may have occurred due to immigration of new peoples from the north, although this is a subject of debate.[34] At a number of sites in southern Korea there are rock art panels that are thought to date from this period, mainly for stylistic reasons.[35]

While the exact date of the introduction of bronzework into Korea is also a matter of debate, it is clear that bronze was being worked by about 700 BCE. Finds include stylistically distinctive daggers, mirrors, and belt buckles, with evidence by the 1st century BCE of a widespread, locally distinctive, bronzeworking culture.[36]

Protohistoric Korea

The time between 300 BCE and the founding and stabilization of the Three Kingdoms around 300 CE is characterized artistically and archaeologically by increasing trade with China and Japan, something that Chinese histories of the time corroborate. The expansionist Chinese invaded and established commanderies in northern Korea as early as the 1st century BCE; they were driven out by the 4th century CE.[37] The remains of some of these, especially that of Lelang, near modern Pyongyang, have yielded many artifacts in a typical Han style.[38]

Chinese histories also record the beginnings of iron works in Korea in the 1st century BCE. Stoneware and kiln-fired pottery also appears to date from this time, although there is controversy over the dates.[39] Pottery of distinctly Japanese origin is found in Korea, and metalwork of Korean origin is found in northeastern China.[40]

Steppes Art

Superb samples of Steppes art – mostly golden jewellery and trappings for horse – are found over a vast expanses of land stretching from Hungary to Mongolia. Dating from the period between the 7th and 3rd centuries BCE, the objects are usually diminutive, as may be expected from nomadic people always on the move. Art of the steppes is primarily an animal art, i.e., combat scenes involving several animals (real or imaginary) or single animal figures (such as golden stags) predominate. The best known of the various peoples involved are the Scythians, at the European end of the steppe, who were especially likely to bury gold items.

Among the most famous finds was made in 1947, when the Soviet archaeologist Sergei Rudenko discovered a royal burial at Pazyryk, Altay Mountains, which featured – among many other important objects – the most ancient extant pile rug, probably made in Persia. Unusually for prehistoric burials, those in the northern parts of the area may preserve organic materials such as wood and textiles that normally would decay. Steppes people both gave and took influences from neighbouring cultures from Europe to China, and later Scythian pieces are heavily influenced by ancient Greek style, and probably often made by Greeks in Scythia.

Near East

The Ain Sakhri Lovers from modern Israel, is a small Natufian carving in calcite, from about 9,000 BCE. Around the same time, the extraordinary site of Göbekli Tepe in eastern Turkey was begun. During the first phase, belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), circles of massive but neatly shaped T-shaped stone pillars were erected – the world's oldest known megaliths.[41] More than 200 pillars in about 20 circles are currently known through geophysical surveys. Each pillar has a height of up to 6 m (20 ft) and weighs up to 10 tons. They are fitted into sockets that were hewn out of the bedrock.[42] In the second phase, belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), the erected pillars are smaller and stood in rectangular rooms with floors of polished lime. On the smoothed surfaces of the pillars there are reliefs of animals, abstract patterns, and some human figures.

By convention, prehistory in the Near East is taken to continue until the rise of the Achaemenid Empire in the 6th century BCE, although writing existed in the region from nearly 2,000 years earlier. On that basis the very rich and long tradition of the art of Mesopotamia, as well as Assyrian sculpture, Hittite art and many other traditions such as the Luristan bronzes all fall under prehistoric art, even if covered with texts extolling the ruler, as many Assyrian palace reliefs are.

Europe

Stone Age

The Art of the Upper Paleolithic includes carvings on antler and bone, especially of animals, as well as the so-called Venus figurines and cave paintings, discussed above. Despite a warmer climate, the Mesolithic period undoubtedly shows a falling-off from the heights of the preceding period. Rock art is found in Scandinavia and northern Russia, and around the Mediterranean in eastern Spain and the earliest of the Rock Drawings in Valcamonica in northern Italy, but not in between these areas.[43][44] Examples of portable art include painted pebbles from the Azilian culture which succeeded the Magdalenian, and patterns on utilitarian objects, like the paddles from Tybrind Vig, Denmark. The Mesolithic statues of Lepenski Vir at the Iron Gate, Serbia date to the 7th millennium BCE and represent either humans or mixtures of humans and fish. Simple pottery began to develop in various places, even in the absence of farming.

Mesolithic

Compared to the preceding Upper Paleolithic and the following Neolithic, there is rather less surviving art from the Mesolithic. The Rock art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin, which probably spreads across from the Upper Paleolithic, is a widespread phenomenon, much less well known than the cave-paintings of the Upper Paleolithic, with which it makes an interesting contrast. The sites are now mostly cliff faces in the open air, and the subjects are now mostly human rather than animal, with large groups of small figures; there are 45 figures at Roca dels Moros. Clothing is shown, and scenes of dancing, fighting, hunting and food-gathering. The figures are much smaller than the animals of Paleolithic art, and depicted much more schematically, though often in energetic poses.[45] A few small engraved pendants with suspension holes and simple engraved designs are known, some from northern Europe in amber, and one from Starr Carr in Britain in shale.[46]

The rock art in the Urals appears to show similar changes after the Paleolithic, and the wooden Shigir Idol is a rare survival of what may well have been a very common material for sculpture. It is a plank of larch carved with geometric motifs, but topped with a human head. Now in fragments, it would apparently have been over 5 metres tall when made.[47]

Neolithic

.jpg.webp)

In Central Europe, many Neolithic cultures, like Linearbandkeramic, Lengyel and Vinča,[48] produced female (rarely male) and animal statues that can be called art, and elaborate pottery decoration in, for example, the Želiesovce and painted Lengyel style.

Megalithic (i.e., large stone) monuments are found in the Neolithic Era from Malta to Portugal, through France, and across southern England to most of Wales and Ireland. They are also found in northern Germany and Poland, as well as in Egypt in the Sahara desert (at Nabta Playa and other sites). The best preserved of all temples and the oldest free standing structures are the Megalithic Temples of Malta. They start in the 5th millennium BC, though some authors speculate on Mesolithic roots. One of the best-known prehistoric sites is Stonehenge, part of the Stonehenge World Heritage Site which contains hundreds of monuments and archaeological sites. Monuments have been found throughout most of Western and Northern Europe, notably at Carnac, France.

The large mound tomb at Newgrange, Ireland, dating to around 3200 BC, has its entrance marked with a massive stone carved with a complex design of spirals. The mound at nearby Knowth has large flat rocks with rock engravings on their vertical faces all around its circumference, for which various meanings have been suggested, including depictions of the local valley, and the oldest known image of the Moon. Many of these monuments were megalithic tombs, and archaeologists speculate that most have religious significance. Knowth is reputed to have approximately one third of all megalithic art in Western Europe.

In the central Alps, the Camunni made some 350,000 petroglyphs: see Rock Drawings in Valcamonica.

Bronze Age

During the 3rd millennium BCE, the Bronze Age began in Europe, bringing with it a new medium for art. The increased efficiency of bronze tools also meant an increase in productivity, which led to a surplus — the first step in the creation of a class of artisans. Because of the increased wealth of society, luxury goods began to be created, especially decorated weapons.

Examples include ceremonial bronze helmets, ornamental ax-heads and swords, elaborate instruments such as lurer, and other ceremonial objects without a practical purpose, such as the oversize Oxborough Dirk. Special objects were made in gold; many more gold objects have survived from Western and Central Europe than from the Iron Age, many mysterious and strange objects ranging from lunulas, apparently an Irish speciality, the Mold Cape and Golden hats. Pottery from Central Europe can be elaborately shaped and decorated. Rock art, showing scenes from the religious rituals have been found in many areas, for example in Bohuslän, Sweden and the Val Camonica in northern Italy.

In the Mediterranean, the Minoan civilization was highly developed, with palace complexes from which sections of frescos have been excavated. Contemporary Ancient Egyptian art and that of other advanced Near Eastern cultures can no longer be treated as "prehistoric".

Iron Age

The Iron Age saw the development of anthropomorphic sculptures, such as the warrior of Hirschlanden, and the statue from the Glauberg, Germany. Hallstatt artists in the early Iron Age favored geometric, abstract designs perhaps influenced by trade links with the Classical world.

The more elaborate and curvilinear La Tène style developed in Europe in the later Iron Age from a centre in the Rhine valley but it soon spread across the continent. The rich chieftain classes appear to have encouraged ostentation and Classical influences such as bronze drinking vessels attest to a new fashion for wine drinking. Communal eating and drinking were an important part of Celtic society and culture and much of their art was often expressed through plates, knives, cauldrons and cups. Horse tack and weaponry were also decorated. Mythical animals were a common motif along with religious and natural subjects and their depiction is a mix between the naturalistic and the stylized. Megalithic art was still sometimes practiced, examples include the carved limestone pillars of the sanctuary at Entremont in modern-day France. Personal adornment included torc necklaces whilst the introduction of coinage provided a further opportunity for artistic expression. The coins of this period are derivatives of Greek and Roman types, but showing the more exuberant Celtic artistic style.

.jpg.webp)

The famous late 4th century BCE Waldalgesheim chariot burial in the Rhineland produced many fine examples of La Tène art including a bronze flagon and bronze plaques with repoussé human figures. Many pieces had curvy, organic styles though to be derived from Classical tendril patterns.

In much of western Europe elements of this artistic style can be discerned surviving in the art and architecture of the Roman colonies. In particular in Britain and Ireland there is a tenuous continuity through the Roman period, enabling Celtic motifs to resurface with new vigour in the Christian Insular art from the 6th century onwards.

The sophisticated Etruscan culture developed from the 9th to 2nd centuries, with considerable influence from the Greeks, before finally being absorbed by the Romans. By the end of the period they had developed writing, but early Etruscan art can be called prehistoric.

Africa

Ancient Egypt falls outside the scope of this article; it had a close relationship with the Sudan in particular, known in this period as Nubia, where there were advanced cultures from the 4th millennium BCE, such as the "A-Group", "C-Group", and the Kingdom of Kush.

Southern Africa

In September 2018, scientists from the University of Bergen, the University of Bordeaux and the University of the Witwatersrand together reported the discovery of the earliest known drawing by Homo sapiens at Blombos Cave, South Africa which is estimated to be 73,000 years old, much earlier than the 43,000 years old artifacts understood to be the earliest known modern human drawings found previously.[2]

There is a significant body of rock painting in the region around Matobo National Park of Zimbabwe dating from as early as 6000 BCE to 500 CE.[49]

Significant San rock paintings exist in the Waterberg area above the Palala River and around Drakensberg in South Africa, some of which are considered to derive from the period 8000 BCE. These images are very clear and depict a variety of human and wildlife motifs, especially antelope. There appears to be a fairly continuous history of rock painting in this area; some of the art clearly dates into the 19th century. They include depictions of horses with riders, which were not introduced to the area until the 1820s.[50]

Namibia, in addition to the Apollo 11 Cave complex, has a significant array of San rock art near Twyfelfontein. This work is several thousand years old, and appears to end with the arrival of pastoral tribes in the area.[51]

Horn of Africa

Laas Geel is a complex of caves and rock shelters in northwestern Somalia. Famous for their rock art, the caves are located in a rural area on the outskirts of Hargeisa. They contain some of the earliest known cave paintings in the Horn of Africa, many of which depict pastoral scenes. Laas Geel's rock art is estimated to date back to somewhere between 9,000–8,000 and 3,000 BCE.

In 2008, archaeologists also announced the discovery of cave paintings in Somalia's northern Dhambalin region, which the researchers suggest includes one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is in the Ethiopian-Arabian style, dated to 1000 to 3000 BCE.[52][53]

Other prehistoric art in the Horn region include stone megaliths and engravings, some of which are 3,500 years old. The town of Dillo in Ethiopia has a hilltop covered with stone stelae. It is one of several such sites in southern Ethiopia dating from historic period (10th–14th centuries).[54]

Saharan Africa

The early art of this region has been divided into five periods:

- Bubalus Period, roughly 12-8 kya

- Round Head Period, roughly 10-8 kya

- Pastoral Period, roughly 7.5-4 kya

- Horse Period, roughly 3-2 kya

- Camel Period, 2,000 years ago to the present

Works of the Bubalus period span the Sahara, with the finest work, carvings of naturalistically depicted megafauna, concentrated in the central highlands. The Round Head Period is dominated by paintings of strangely shaped human forms, and few animals, suggesting the artists were foragers.These artists may have been producing rock art 2,000 years before domestication.[55] These works are largely limited to Tassili n'Ajjer and the Tadrart Acacus. Some works show figures with bows near herds of cattle and a reunion of members near cattle.[56] Round heads are found in Tassili, Jebel Uweinat and Ennedi, which may indicate similar cultures between these populations.[55] Other animals represented in the Round head art are hippopotamus, elephant, and bovids. Animals like antelope and mouflon are also represented; fauna remains have been found in archaeological sites during excavations.[55] About 90% of Round Head art is animal representation.[55] Toward the end of the period, images of domesticated animals, as well as decorative clothing and headdresses appear. Some domesticated animals are cattle from the Bovidae family.[55]

Pastoral Period art was more focused on domestic scenes, including herding and dancing. As well as hunting scenes of mouflon.[55] Unlike in the Round Head art, the bow is relevant to Pastoral art since hunting scenes were depicted during this time.[57] Pastoral figures are seen on the same wall of Round Heads except they are along the borders. The foragers may have been respecting the previous artwork and did not paint over the figures.[55] The quality of artwork declined, as figures became more simplified.[58]

The Horse Period began in the eastern Sahara and spread west. Depictions from this period include carvings and paintings of horses, chariots, and warriors with metal weapons, although there are also frequent depictions of wildlife such as giraffes. Humans are generally depicted in a stylized way. Some of the chariot art bears resemblance to temple carvings from ancient Egypt. Occasionally, art panels are accompanied by Tifinagh script, still in use by the Berber people and the Tuareg today; however, modern Tuareg are generally unable to read these inscriptions. The final Camel period features carvings and paintings in which camels predominate, but also include humans with swords, and later, guns; the art of this time is relatively crude.[59]

North Africa

The Americas

North America

.jpg.webp)

Belonging in the Lithic stage, the oldest known art in the Americas is the Vero Beach bone, possibly a mammoth bone, etched with a profile of walking mammoth that dates back to 11,000 BCE.[60] The oldest known painted object in the Americas is the Cooper Bison Skull from 10,900 to 10,200 BCE.[61]

Mesoamerica

The ancient Olmec "Bird Vessel" and bowl, both ceramic and dating to circa 1000 BC as well as other ceramics were produced in kilns capable of exceeding approximately 900 °C. The only other prehistoric culture known to have achieved such high temperatures is that of Ancient Egypt.[62]

Much Olmec art is highly stylized and uses an iconography reflective of the religious meaning of the artworks. Some Olmec art, however, is surprisingly naturalistic, displaying an accuracy of depiction of human anatomy perhaps equaled in the pre-Columbian New World only by the best Maya Classic-era art. Olmec art-forms emphasize monumental statuary and small jade carvings. A common theme is to be found in representations of a divine jaguar. Olmec figurines were also found abundantly through their period.

South America

Lithic age art in South America includes Monte Alegre culture rock paintings created at Caverna da Pedra Pintada dating back to 9250–8550 BCE.[63][64] Guitarrero Cave in Peru has the earliest known textiles in South America, dating to 8000 BCE.[65]

Peru and the central Andes

Lithic and preceramic periods

Peru, including an area of the central Andes stretching from the northern part of the country to northern Chile, has a rich cultural history, with evidence of human habitation dating to roughly 10,000 BCE.[66] Prior to the emergence of ceramics in this region around 1850 BCE, cave paintings and beads have been found. These finds include rock paintings that controversially date as far back as 9500 BCE in the Toquepala Caves.[67] Burial sites in Peru like one at Telarmachay as old as 8600–7200 BCE contained evidence of ritual burial, with red ocher and bead necklaces.[68]

The earliest ceramics that appear in Peru may have been imported from the Validivia region; indigenous pottery production almost certainly arrived in the highlands around 1800 BCE at Kotosh, and on the coast at La Florida c. 1700 BCE. Older calabash gourd vessels with human faces burned into them were found at Huaca Prieta, a site dating to 2500–2000 BCE.[69] Huaca Prieta also contained some early patterned and dyed textiles made from twisted plant fibers.[70]

Initial Period and First Horizon

The Initial Period in Central Andean cultures lasted roughly from 1800 BCE to 900 BCE. Textiles from this time found at Huaca Prieta are of astonishing complexity, including images such as crabs whose claws transform into snakes, and double-headed birds. Many of these images are similar to optical illusions, where which image dominates depends in part on which the viewer chooses to see. Other portable artwork from this time includes decorated mirrors, bone and shell jewelry, and unfired clay female effigies.[71] Public architecture, including works estimated to require the movement of more than 100,000 tons of stone, are to be found at sites like Kotosh, El Paraíso, Peru, and La Galgada (archaeological site). Kotosh, a site in the Andean highlands, is especially noted as the site of the Temple of the Crossed Hands, in which there are two reliefs of crossed forearms, one pair male, one pair female.[72] Also of note is one of South America's largest ceremonial sites, Sechín Alto. This site's crowning work is a twelve-story platform, with stones incised with military themes.[73] The architecture and art of the highlands, in particular, laid down the groundwork for the rise of the Chavín culture.[74]

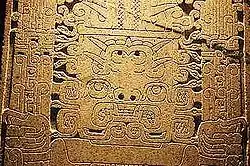

The Chavín culture dominated the central Andes during the First Horizon, beginning around 900 BCE, and is generally divided into two stages. The first, running until about 500 BCE, represented a significant cultural unification of the highland and coastal cultures of the time. Imagery in all manner of art (textiles, ceramics, jewelry, and architectural) included sometimes fantastic imagery such as jaguars, snakes, and human–animal composites, much of it seemingly inspired by the jungles to the east.[75]

The later stage of the Chavín culture is primarily represented by a significant architectural expansion of the Chavín de Huantar site around 500 BCE, accompanied by a set of stylistic changes. This expansion included, among other changes, over forty large stone heads, whose reconstructed positions represent a transformation from human to supernatural animal visages. Much of the other art at the complex from this time contains such supernatural imagery.[76] The portable art associated with this time included sophisticated metalworking, including alloying of metals and soldering.[77] Textiles found at sites like Karwa clearly depict Chavín cultural influences,[78] and the Cupisnique style of pottery disseminated by the Chavín would set standards all across the region for later cultures.[79] (The vessel pictured at the top of this article, while from the later Moche culture, is representative of the stirrup-spouted vessels of the Chavín.)

Early Intermediate Period

The Early Intermediate Period lasted from about 200 BCE to 600 CE. Late in the First Horizon, the Chavín culture began to decline, and other cultures, predominantly in the coastal areas, began to develop. The earliest of these was the Paracas culture, centered on the Paracas Peninsula of central Peru. Active from 600 BCE to 175 BCE, their early work clearly shows Chavín influence, but a locally distinctive style and technique developed. It was characterized by technical and time-consuming detail work, visually colorful, and a profusion visual elements. Distinctive technical differences include painting on clay after firing, and embroidery on textiles.[80] One notable find is a mantle that was clearly used for training purposes; it shows obvious indications of experts doing some of the weaving, interspersed with less technically proficient trainee work.[81]

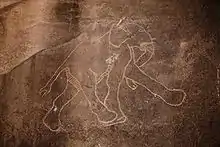

The Nazca culture of southern Peru, which is widely known for the enormous figures traced on the ground by the Nazca lines in southern Peru, shared some similarities with the Paracas culture, but techniques (and scale) differed. The Nazca painted their ceramics with slip, and also painted their textiles.[82] Nazca ceramics featured a wide variety of subjects, from the mundane to the fantastic, including utilitarian vessels and effigy figures. The Nazca also excelled at goldsmithing, and made pan pipes from clay in a style not unlike the pipes heard in music of the Andes today.[83]

The famous Nazca lines are accompanied by temple-like constructions (showing no sign of permanent habitation) and open plazas that presumably had ritual purposes related to the lines. The lines themselves are laid out on a sort of natural blackboard, where a thin layer of dark stone covers lighter stone; the lines were thus created by simply removing the top layer where desired, after using surveying techniques to lay out the design.[84]

In the north of Peru, the Moche culture dominated during this time. Also known as Mochica or Early Chimú, this warlike culture dominated the area until about 500 CE, apparently using conquest to gain access to critical resources along the desert coast: arable land and water. Moche art is again notably distinctive, expressive and dynamic in a way that many other Andean cultures were not. Knowledge of the period has been notably expanded by finds like the pristine royal tombs at Sipán.[85]

The Moche very obviously absorbed some elements of the Chavín culture, but also absorbed ideas from smaller nearby cultures that they assimilated, such as the Recuay culture and the Vicús.[86] They made fully sculpted ceramic animal figures, worked gold, and wove textiles. The art often featured everyday images, but seemingly always with a ritual intent.[87]

In its later years, the Moche came under the influence of the expanding Huari empire. The Cerro Blanco site of Huaca del Sol appears to have been the Moche capital. Largely destroyed by natural events around 600 CE, it was further damaged by Spanish conquistadors searching for gold, and continues with modern looters.[88]

Middle Horizon

The Middle Horizon lasted from 600 CE to 1000 CE, and was dominated by two cultures: the Huari and the Tiwanaku. The Tiwanaku (also spelled Tiahuanaco) culture arose near Lake Titicaca (on the modern border between Peru and Bolivia), while the Wari culture arose in the southern highlands of Peru. Both cultures appear to have been influenced by the Pukara culture, which was active during the Early Intermediate in between the primary centers of the Wari and Tiwanaku.[89] These cultures both had wide-ranging influence, and shared some common features in their portable art, but their monumental arts were somewhat distinctive.[90]

The monumental art of the Tiwanaku demonstrated technical prowess in stonework, including fine detailed reliefs, and monoliths such as the Ponce monolith (photo to the left), and the Sun Gate, both in the main Tiwanaku site. The portable art featured "portrait vessels", with figured heads on ceramic vessels, as well as natural imagery like jaguars and raptors.[91] A full range of materials, from ceramics to textiles to wood, bone, and shell, were used in creative endeavours. Textiles with a weave of 300 threads per inch (80 threads per cm) have been found at Tiwanaku sites.[92]

The Wari dominated an area from northern to central Peru, with their main center near Ayacucho. Their art is distinguished from the Tiwanaku style by the use of bolder colors and patterns.[93] Notable among Wari finds are tapestry garments, presumed to be made for priests or rulers to wear, often bearing abstract geometric designs of significant complexity, but also bearing images of animals and figures.[94] Wari ceramics, also of high technical quality, are similar in many ways to those of the preceding cultures, where local influences from fallen cultures, like the Moche, are still somewhat evident. Metalwork, while rarely found due to its desirability by looters, shows elegant simplicity and, once more, a high level of workmanship.[95]

Late Intermediate Period

Following the decline of the Wari and Tiwanaku, the northern and central coastal areas were somewhat dominated by the Chimú culture, which included notable subcultures like the Lambayeque (or Sicán) and Chancay cultures. To the south, coastal cultures dominated in the Ica region, and there was a significant cultural crossroads at Pachacamac, near Lima.[96] These cultures would dominate from about 1000 CE until the 1460s and 1470s, as the Inca Empire began to take shape and eventually absorbed the geographically smaller nearby cultures.

Chimú and Sicán Cultures

The Chimú culture in particular was responsible for an extremely large number of artworks. Its capital city, Chan Chan, appears to have contained building that appeared to function as museums—they seem to have been used for displaying and preserving artwork. Much of the artwork from Chan Chan in particular has been looted, some by the Spanish after the Spanish conquest.[96] The art from this time at times displays amazing complexity, with "multimedia" works that require artists working together in a diversity of media, including materials believed to have come from as far away as Central America. Items of increasing splendor or value were produced, apparently as the society became increasing stratified.[97] At the same, the quality of some of the work declined, as demand for pieces pushed production rates up and values down.[98]

The Sicán culture flourished from 700 CE to about 1400 CE, although it came under political domination of the Chimú around 1100 CE, at which time many of its artists may have moved to Chan Chan. There was significant copperworking by the Sicán, including what seems to be a sort of currency based on copper objects that look like axes.[99] Artwork includes burial masks, beakers and metal vessels that previous cultures traditionally made of clay. The metalwork of the Sicán was particularly sophisticated, with innovations including repoussé and shell inlay. Sheet metal was also often used to cover other works.[100]

Prominent in Sicán iconography is the Sicán deity, which appears on all manner of work, from the portable to the monumental. Other imagery includes geometric and wave patterns, as well as scenes of fishing and shell diving.[101]

Chancay culture Chancay culture, before it was subsumed by the Chimú, did not feature notable monumental art. Ceramics and textiles were made, but the quality and skill level was uneven. Ceramics are generally black on white, and often suffer from flaws like poor firing, and drips of the slip used for color; however, fine examples exist. Textiles are overall of a higher quality, including the use of painted weaves and tapestry techniques, and were produced in large quantities.[102] The color palette of the Chancay was not overly bold: golds, browns, white, and scarlet predominate.[103]

Pachacamac Pachacamac is a temple site south of Lima, Peru that was an important pilgrimage center into Spanish colonial times. The site boasts temple constructions from several periods, culminating in Inca constructions that are still in relatively good condition. The temples were painted with murals depicting plants and animals. The main temple contained a carved wooden sculpture akin to a totem pole.[103]

Ica culture The Ica region, which had been dominated by the Nazca, was fragmented into several smaller political and culture groups. The pottery produced in this region was of the highest quality at the time, and its aesthetics would be adopted by the Inca when they conquered the area.[104]

Late Horizon and Inca culture

This time period represents the era in which the culture of the central Andes is almost completely dominated by the Inca Empire, which began its expansion in 1438. It lasted until the Spanish conquest in 1533. The Inca absorbed much technical skill from the cultures they conquered, and disseminated it, along with standard shapes and patterns, throughout their area of influence, which extended from Quito, Ecuador to Santiago, Chile. Inca stonework is notably proficient; giant stones are set so tightly without mortar that a knife blade will not fit in the gap.[105] Many of the Inca's monumental structures deliberately echoed the natural environment around them; this is particularly evident in some of the structures at Machu Picchu.[106] The Inca laid the city of Cusco in the shape of a puma, with the head of the puma at Sacsayhuaman,[107] a shape that is still discernible in aerial photographs of the city today.

The iconography of Inca art, while clearly drawing from its many predecessors, is still recognizably Inca. Bronzework owes a clear debt to the Chimú, as do a number of cultural traditions: the finest goods were reserved to the rulers, who wore the finest textiles, and ate and drank from gold and silver vessels.[108] As a result, Inca metalwork was relatively rare, and an obvious source of plunder for the conquering Spanish.

Textiles were widely prized within the empire, in part as they were somewhat more portable in the far-flung empire.[109]

Ceramics were made in large quantities, and, as with other media, in standardized shapes and patterns. One common shape is the urpu, a distinctive urn shape that came in a wide variety of standard capacities, much as modern storage containers do.[110] In spite of this standardization, many local areas retained some distinctive aspects of their culture in the works they produced; ceramics produced in areas under significant Chimú control prior to the Inca rule still retain characteristics indicative of that style.[111]

Following the Spanish conquest, the art of the central Andes was significantly affected by the conflict and diseases brought by the Spanish. Early colonial period art, began to show influences of both Christianity and Inca religious and artistic ideas, and eventually also began to encompass new techniques brought by the conquerors, including oil painting on canvas.[112]

Early ceramics in northern South America

The earliest evidence of decorated pottery in South America is to be found in two places. A variety of sites in the Santarém region of Brazil contain ceramic sherds dating to a period between 5000 and 3000 BCE.[113] Sites in Colombia, at Monsú and San Jacinto contained pottery finds in different styles, and date as far back as 3500 BCE.[114] This is an area of active research and subject to change.[115] The ceramics were decorated with curvilinear incisions. Another ancient site at Puerto Hormiga in the Bolívar Department of Colombia dating to 3100 BCE contained pottery fragments that included figured animals in a style related to later Barrancoid cultural finds in Colombia and Venezuela.[114] Valdivia, Ecuador also has a site dated to roughly 3100 BCE containing decorated fragments, as well as figurines, many represent nude females. The Valdivian style stretched as far south as northern Peru,[116] and may, according to Lavallée, yet yield older artifacts.[113]

By 2000 BCE, pottery was evident in eastern Venezuela. The La Gruta style, often painted in red or white, included incised animal figures in the ceramic, as well as ceramic vessels shaped as animal effigies. The Rancho Peludo style of western Venezuela featured relatively simple textile-type decorations and incisions.[116] Finds in the central Andes dating to 1800 BCE and later appear to be derived from the Valdivian tradition of Ecuador.[117]

Early art in eastern South America

Relatively little is known about the early settlement of much of South America east of the Andes. This is due to the lack of stone (generally required for leaving durable artifacts), and a jungle environment that rapidly recycles organic materials. Beyond the Andean regions, where the inhabitants were more clearly related to the early cultures of Peru, early finds are generally limited to coastal areas and those areas where there are stone outcrops. While there is evidence of human habitation in northern Brazil as early as 8000 BCE,[118] and rock art of unknown (or at best uncertain) age, ceramics appear to be the earliest artistic artifacts. The Mina civilization of Brazil (3000–1600 BCE) had simple round vessels with a red wash, that were stylistic predecessors to later Bahia and Guyanese cultures.[116]

Southern South America

The southern reaches of South America show evidence of human habitation as far back as 10,000 BCE. A site at Arroio do Fosseis on the pampa in southern Brazil has shown reliable evidence to that time,[119] and the Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of the continent has been occupied since 7000 BCE.[120] Artistic finds are scarce; in some parts of Patagonia ceramics were never made, only being introduced by contact with Europeans.[121]

Oceania

Australia

From earliest times Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders have been creating distinctive patterns of art. Much of the art is transitory, drawn in sand or on the human body to illustrate a place, a totem, or a cultural story. Early surviving artworks are mostly rock paintings. Some are called X-ray paintings because they show the bones and organs of the animals they depict. Some Aboriginal art appears as abstract to modern viewers; Aboriginal art employs geometrical figures, dots and lines to present the story being told.

The Gwion Gwion rock art are one of many styles of rock art found in Western Australia. They are predominantly human figures drawn in fine detail with accurate anatomical proportioning. They are usually dated to be at least 17,000 years old, and there have been suggestions they are as much as 70,000 years old.[122] The Sydney rock engravings are also a prominent rock art site in the country.[123]

Polynesia

The natives of Polynesia have a distinct artistic heritage. While many of their artifacts were made with organic materials and thus lost to history, some of their most striking achievements survive in clay and stone. Among these are numerous pottery fragments from western Oceania, from the late 2nd millennium BCE. Also, the natives of Polynesia left scattered around their islands Petroglyphs, stone platforms or Marae, and sculptures of ancestor figures, the most famous of which are the Moai of Easter Island.

References

Notes

- "The term "prehistoric" ceases to be valid some thousands of years BCE in the Middle East but remains a warranted description down to about 500 A.D. in Ireland".[1]

Citations

- A. T. L. 1967, p. 95.

- St. Fleur, Nicholas (12 September 2018). "Oldest Known Drawing by Human Hands Discovered in South African Cave". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving". Nature.

- "Shell 'art' made 300,000 years before humans evolved – New Scientist". New Scientist.

- Joordens, Josephine C. A.; d'Errico, Francesco; Wesselingh, Frank P.; Munro, Stephen; de Vos, John; Wallinga, Jakob; Ankjærgaard, Christina; Reimann, Tony; Wijbrans, Jan R.; Kuiper, Klaudia F.; Mücher, Herman J. (2015). "Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving". Nature. 518 (7538): 228–231. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..228J. doi:10.1038/nature13962. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25470048. S2CID 4461751.

- Wilford, John Noble (13 October 2011). "In African Cave, Signs of an Ancient Paint Factory". New York Times. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- The Metropolitan Museum of New York City Introduction to Prehistoric Art Retrieved 12 May 2012

- Chase 2005, pp. 145–146.

- Henshilwood, Christopher; Niekerk, Karen Loise van. "South Africa's Blombos cave is home to the earliest drawing by a human". The Conversation. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- "Discovery of the earliest drawing". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- D. L. Hoffmann; C. D. Standish; M. García-Diez; P. B. Pettitt; J. A. Milton; J. Zilhão; J. J. Alcolea-González; P. Cantalejo-Duarte; H. Collado; R. de Balbín; M. Lorblanchet; J. Ramos-Muñoz; G.-Ch. Weniger; A. W. G. Pike (2018). "U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art". Science. 359 (6378): 912–915. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..912H. doi:10.1126/science.aap7778. PMID 29472483.

- Marris, Emma (22 February 2018). "Neanderthal artists made oldest-known cave paintings". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-02357-8.

- Feehly, Conor (6 July 2021). "Beautiful Bone Carving From 51,000 Years Ago Is Changing Our View of Neanderthals". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Leder, Dirk; et al. (5 July 2021). "A 51,000-year-old engraved bone reveals Neanderthals' capacity for symbolic behaviour". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 594 (9): 1273–1282. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01487-z. PMID 34226702. S2CID 235746596. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Zimmer, Carl (7 November 2018). "In Cave in Borneo Jungle, Scientists Find Oldest Figurative Painting in the World – A cave drawing in Borneo is at least 40,000 years old, raising intriguing questions about creativity in ancient societies". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Aubert, M.; et al. (7 November 2018). "Palaeolithic cave art in Borneo". Nature. 564 (7735): 254–257. Bibcode:2018Natur.564..254A. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0679-9. PMID 30405242. S2CID 53208538.

- Magazine, Smithsonian; Gershon, Livia. "Is This 51,000-Year-Old Deer Bone Carving an Early Example of Neanderthal Art?". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Fox-Skelly, Jasmin. "The animals with an eye for art". www.bbc.com.

- "Indonesian Cave Paintings As Old As Europe's Ancient Art". NPR.org. 8 October 2014.

- Portal 2000, p. 25.

- Portal 2000, p. 26.

- Coulson & Campbell 2001, pp. 150–155.

- Thackeray et al. 1981.

- Mathpal, Yashodhar (1984). Prehistoric Painting Of Bhimbetka. Abhinav Publications. p. 220. ISBN 978-81-7017-193-5.

- Tiwari, Shiv Kumar (2000). Riddles of Indian Rockshelter Paintings. Sarup & Sons. p. 189. ISBN 978-81-7625-086-3.

- Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka (PDF). UNESCO. 2003. p. 16.

- Mithen, Steven (2011). After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000 – 5000 BC. Orion. p. 524. ISBN 978-1-78022-259-2.

- Javid, Ali; Jāvīd, ʻAlī; Javeed, Tabassum (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. Algora Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-87586-484-6.

- Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan (2005). Azerbaijan. Cavendish Square Publishing. pp. 18. ISBN 978-0-7614-2011-8.

- Azerbaijan: Mosques, Turrets, Palaces. Corvina Kiadó. 1979. p. 8. ISBN 978-963-13-0321-6.

- A Historical Atlas of Azerbaijan. Rosen Pub Group. 2004. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8239-4497-2.

- "The Rock Engravings of Gobustan". donsmaps.com. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Portal 2000, p. 27.

- Portal 2000, p. 29.

- Portal 2000, p. 33.

- Portal 2000, pp. 34–35.

- Portal 2000, p. 38.

- Portal 2000, p. 39.

- Portal 2000, p. 40.

- Portal 2000, p. 41.

- Sagona, Claudia (25 August 2015). The Archaeology of Malta. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-107-00669-0. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Curry, Andrew (November 2008). "Gobekli Tepe: The World's First Temple?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Sandars 1968, pp. 75–98.

- "Rock Drawings in Valcamonica" (PDF).

- Sandars 1968, pp. 87–96.

- "11,000 year old pendant is earliest known Mesolithic art in Britain", University of York

- Geggel, Laura (25 April 2018). "This Eerie, Human-Like Figure Is Twice As Old As Egypt's Pyramids". Live Science. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Borić, Dušan; Hanks, Bryan; Šljivar, Duško; Kočić, Miroslav; Bulatović, Jelena; Griffiths, Seren; Doonan, Roger; Jacanović, Dragan (June 2018). "Enclosing the Neolithic World: A Vinča Culture Enclosed and Fortified Settlement in the Balkans". Current Anthropology. 59 (3): 336–345. doi:10.1086/697534. hdl:11573/1545302. S2CID 150068332.

- Coulson & Campbell 2001, p. 86.

- Coulson & Campbell 2001, pp. 80–82.

- "Unesco World Heritage announcement on Twyfelfontein". Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- Mire, Sada (2008). "The Discovery of Dhambalin Rock Art Site, Somaliland". African Archaeological Review. 25 (3–4): 153–168. doi:10.1007/s10437-008-9032-2. S2CID 162960112. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- Alberge, Dalya (17 September 2010). "UK archaeologist finds cave paintings at 100 new African sites". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- Coulson & Campbell 2001, p. 147.

- Soukopova 2012, CH.4.

- Barbaza, Michel (20 October 2018). "Cultures of peace and the art of war in Saharan rock art" (PDF). Quaternary International. 491: 125–135. Bibcode:2018QuInt.491..125B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.09.062. S2CID 134359423.

- Soukopova 2012, CH.3.

- Coulson & Campbell 2001, pp. 156–160.

- Coulson & Campbell 2001, pp. 160–162, 205.

- "Ice Age Art from Florida." Archived 26 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine Past Horizons. 23 June 2011 (retrieved 23 June 2011)

- Bement, Leland C. Bison hunting at Cooper site: where lightning bolts drew thundering herds. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999: 37, 43, 176. ISBN 978-0-8061-3053-8.

- Friedman, Florence Dunn (September 1998). "Ancient Egyptian faience". Archived from the original on 20 October 2004. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- Wilford, John Noble. Scientist at Work: Anna C. Roosevelt; Sharp and To the Point In Amazonia. New York Times. 23 April 1996

- "Dating a Paleoindian Site in the Amazon in Comparison with Clovis Culture." Science. March 1997: Vol. 275, no. 5308, pp. 194801952. (retrieved 1 November 2009)

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 17.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 88.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 94.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 115.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 186.

- Bruhns 1994, p. 80.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 19–20.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 21.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 27.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 22.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 28–29.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 40.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 44.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 46.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 49.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 50.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 58.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 67.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 74–75.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 78–82.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 83.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 88.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 86.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 92.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 121–123.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 119.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 131–134.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 136.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 138–139.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 146–148.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 149–150.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 151.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 153.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 154.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 156.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 156–158.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 160.

- Stone-Miller 1995, pp. 175–177.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 179.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 180.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 181.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 190.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 194.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 186.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 209.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 215.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 216.

- Stone-Miller 1995, p. 217.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 182.

- Bruhns 1994, pp. 116–117.

- Lavallée 1995, pp. 176–182.

- Bruhns 1994, pp. 117–118.

- Bruhns 1994, p. 119.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 113.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 108.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 112.

- Lavallée 1995, p. 187.

- Bradshaw Foundation. "The Bradshaw Paintings – Australian Rock Art Archive". Bradshaw Foundation.

- Bowdler, Sandra. "Balls Head: the excavation of a Port Jackson rock shelter. Records of the Australian Museum 28(7): 117–128, plates 17–21. [4 October 1971]" (PDF). Australian Museum Scientific Publications. Australian Museum. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

Sources

- Arbib, Michael A (2006). Action to language via the mirror neuron system: The Mirror Neuron System. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84755-1.

- A. T. L. (1967). "Reviewed Work: Prehistoric Art by T. G. E. Powell". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 97 (1): 95–96. JSTOR 25509644.

- Bailey, Douglass (2005). Prehistoric Figurines: Representation and Corporeality in the Neolithic. Routledge Publishers. ISBN 978-0-415-33152-4.

- Bruhns, Karen O (1994). Ancient South America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27761-7.

- Chase, Philip G (2005). The Emergence of Culture: The Evolution of a Uniquely Human Way of Life. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-387-30512-7.

- Coulson, David; Campbell, Alec (2001). African Rock Art. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8109-4363-6.

- Lavallée, Danièle (1995). The First South Americans. Bahn, Paul G (trans.). University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-0-87480-665-6.

- Portal, Jane (2000). Korea: Art and Archaeology. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28202-1.

- Sandars, Nancy K. (1968). Prehistoric Art in Europe (1st ed.). Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art).

- Soukopova, Jitka (2012). Round heads: the earliest rock paintings in the Sahara. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

- Stone-Miller, Rebecca (1995). Art of the Andes. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20286-9.

- Thackeray, Anne I.; Thackeray, JF; Beaumont, PB; Vogel, JC; et al. (2 October 1981). "Dated Rock Engravings from Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa". Science. 214 (4516): 64–67. Bibcode:1981Sci...214...64T. doi:10.1126/science.214.4516.64. PMID 17802575. S2CID 29714094.

External links

| Library resources about Prehistoric art |

- RockArtScandinavia Tanums Hällristningsmuseum Underslös. Rock art research centre.

- EuroPreArt database of European Prehistoric Art

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

.jpg.webp)