History of Gabon

Little is known of the history of Gabon prior to European contact. Bantu migrants settled the area beginning in the 14th century. Portuguese explorers and traders arrived in the area in the late 15th century. The coast subsequently became a center of the transatlantic slave trade with European slave traders arriving to the region in the 16th century. In 1839 and 1841, France established a protectorate over the coast. In 1849, captives released from a captured slave ship founded Libreville. In 1862–1887, France expanded its control including the interior of the state, and took full sovereignty. In 1910 Gabon became part of French Equatorial Africa and in 1960, Gabon became independent.

| History of Gabon |

|---|

|

At the time of Gabon's independence, two principal political parties existed: the Gabonese Democratic Bloc (BDG), led by Léon M'Ba, and the Gabonese Democratic and Social Union (UDSG), led by Jean-Hilaire Aubame. In the first post-independence election, held under a parliamentary system, neither party was able to win a majority; the leaders subsequently agreed against a two-party system and ran with a single list of candidates. In the February 1961 election, held under the new presidential system, M'Ba became president and Aubame became foreign minister. The single-party solution disintegrated in 1963, and there was a single-day bloodless coup in 1964. In March 1967, Leon M'Ba and Omar Bongo were elected president and vice president. M'Ba died later that year. Bongo declared Gabon a one-party state, dissolved the BDG and established the Gabonese Democratic Party (PDG). Sweeping political reforms in 1990 led to a new constitution, and the PDG garnered a large majority in the country's first multi-party elections in 30 years. Despite discontent from opposition parties, Bongo remained president until his death in 2009.

Early history

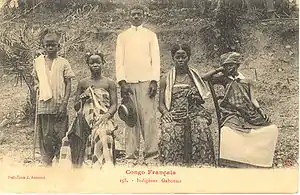

The societies of the indigenous Pygmies were largely displaced from about AD 1000 onwards by migrating Bantu peoples from the north, such as the Fang.[1] Little is known of tribal life before European contact, but tribal art suggests a rich cultural heritage.

Gabon's first confirmed European visitors were Portuguese explorers and traders who arrived in the late 15th century. At this time, the southern coast was controlled by the Kingdom of Loango.[2] The Portuguese settled on the offshore islands of São Tomé, Príncipe, and Fernando Pó, but were regular visitors to the coast.

They named the Gabon region after the Portuguese word gabão — a coat with sleeve and hood resembling the shape of the Komo River estuary. More European merchants came to the region in the 16th century, trading for slaves, ivory and tropical woods.[1][2]

French colonial period

In 1838 and 1841, France established a protectorate over the coastal regions of Gabon by treaties with Gabonese coastal chiefs.

American missionaries from New England established a mission at the mouth of the Komo River in 1842. In 1849, the French authorities captured an illegal slave ship and freed the captives on board. The captives were released near the mission station, where they founded a settlement which was called Libreville (French for "free town")

French explorers penetrated Gabon's dense jungles between 1862 and 1887. The most famous, Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, used Gabonese bearers and guides in his search for the headwaters of the Congo river. France occupied Gabon in 1885, but did not administer it until 1903. Gabon's first political party, the Jeunesse Gabonais, was founded around 1922.

In 1910 Gabon became one of the four territories of French Equatorial Africa. On 15 July 1960 France agreed to Gabon becoming fully independent.[3] On 17 August 1960 Gabon became an independent country.

Independence

Gabonese Republic | |

|---|---|

| 1968–1990 | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital | Libreville |

| Government | One-party republic |

| President | |

• 1968–1990 | Omar Bongo |

| History | |

| 19 March 1967 | |

| 12 March 1968 | |

| 16 September 1990 | |

| Currency | CFA franc |

| ISO 3166 code | GA |

| Today part of | Gabon |

At the time of Gabon's independence in 1960, two principal political parties existed: the Gabonese Democratic Bloc (BDG), led by Léon M'Ba, and the Gabonese Democratic and Social Union (UDSG), led by Jean-Hilaire Aubame. In the first post-independence election, held under a parliamentary system, neither party was able to win a majority. The BDG obtained support from three of the four independent legislative deputies, and M'Ba was named Prime Minister. Soon after concluding that Gabon had an insufficient number of people for a two-party system, the two party leaders agreed on a single list of candidates. In the February 1961 election, held under the new presidential system, M'Ba became president and Aubame became foreign minister.

This one-party system appeared to work until February 1963, when the larger BDG element forced the UDSG members to choose between a merger of the parties or resignation. The UDSG cabinet ministers resigned, and M'Ba called an election for February 1964 and a reduced number of National Assembly deputies (from 67 to 47). The UDSG failed to muster a list of candidates able to meet the requirements of the electoral decrees. When the BDG appeared likely to win the election by default, the Gabonese military toppled M'Ba in a bloodless coup on 18 February 1964. French troops re-established his government the next day. Elections were held in April 1964 with many opposition participants. BDG-supported candidates won 31 seats and the opposition 16. Late in 1966, the constitution was revised to provide for automatic succession of the vice president should the president die in office. In March 1967, Leon M'Ba and Omar Bongo (then known as Albert Bongo) were elected President and Vice President, with the BDG winning all 47 seats in the National Assembly. M'Ba died later that year, and Omar Bongo became president.

In March 1968 Bongo declared Gabon a one-party state by dissolving the BDG and establishing a new party: the Gabonese Democratic Party (Parti Démocratique Gabonais) (PDG). He invited all Gabonese, regardless of previous political affiliation, to participate. Bongo was elected President in February 1973; in April 1975, the office of vice president was abolished and replaced by the office of prime minister, who had no right to automatic succession. Bongo was re-elected president in December 1979 and November 1986 to 7-year terms. Using the PDG as a tool to submerge the regional and tribal rivalries that divided Gabonese politics in the past, Bongo sought to forge a single national movement in support of the government's development policies.

Economic discontent and a desire for political liberalization provoked violent demonstrations and strikes by students and workers in early 1990. In response to worker grievances, Bongo negotiated on a sector-by-sector basis, making significant wage concessions. In addition, he promised to open up the PDG and to organize a national political conference in March–April 1990 to discuss Gabon's future political system. The PDG and 74 political organizations attended the conference. Participants essentially divided into two loose coalitions, the ruling PDG and its allies, and the United Front of Opposition Associations and Parties, consisting of the breakaway Morena Fundamental and the Gabonese Progress Party.

The April 1990 conference approved sweeping political reforms, including creation of a national Senate, decentralization of the budgetary process, freedom of assembly and press, and cancellation of the exit visa requirement. In an attempt to guide the political system's transformation to multiparty democracy, Bongo resigned as PDG chairman and created a transitional government headed by a new Prime Minister, Casimir Oyé-Mba. The Gabonese Social Democratic Grouping (RSDG), as the resulting government was called, was smaller than the previous government and included representatives from several opposition parties in its cabinet. The RSDG drafted a provisional constitution in May 1990 that provided a basic bill of rights and an independent judiciary but retained strong executive powers for the president. After further review by a constitutional committee and the National Assembly, this document came into force in March 1991. Under the 1991 constitution, in the event of the president's death, the Prime Minister, the National Assembly president, and the defense minister were to share power until a new election could be held.

Opposition to the PDG continued, however, and in September 1990, two coup d'état attempts were uncovered and aborted. Despite anti-government demonstrations after the untimely death of an opposition leader, the first multiparty National Assembly elections in almost 30 years took place in September–October 1990, with the PDG garnering a large majority.

Following President Bongo's re-election in December 1993 with 51% of the vote, opposition candidates refused to validate the election results. Serious civil disturbances led to an agreement between the government and opposition factions to work toward a political settlement. These talks led to the Paris Accords in November 1994, under which several opposition figures were included in a government of national unity, and constitutional reforms were approved in a referendum in 1995. This arrangement soon broke down, however, and the 1996 and 1997 legislative and municipal elections provided the background for renewed partisan politics. The PDG won a landslide victory in the legislative election, but several major cities, including Libreville, elected opposition mayors during the 1997 local election.

Modern times

President Bongo coasted to easy re-elections in December 1998 and November 2005, with large majorities of the vote against a divided opposition. While Bongo's major opponents rejected the outcome as fraudulent, some international observers characterized the results as representative despite any perceived irregularities. Legislative elections held in 2001–2002, which were boycotted by a number of smaller opposition parties and were widely criticized for their administrative weaknesses, produced a National Assembly almost completely dominated by the PDG and allied independents.

Omar Bongo died at a Spanish hospital on 8 June 2009.[4]

His son Ali Bongo Ondimba was elected president in the August 2009 presidential election.[5] He was re-elected in August 2016, in elections marred by numerous irregularities, arrests, human rights violations and post-election violence.[6][7]

On 24 October 2018, Ali Bongo Ondimbao was hospitalized in Riyadh for an undisclosed illness. On 29 November 2018 Bongo was transferred to a military hospital in Rabat to continue recovery.[8] On 9 December 2018 it was reported by Gabon's Vice President Moussavou that Bongo suffered a stroke in Riyadh and has since left the hospital in Rabat and is currently recovering at a private residence in Rabat.[9] Since 24 October 2018 Bongo has not been seen in public and due to lack of evidence that he is either alive or dead many have speculated if he is truly alive or not.[10] On 1 January 2019 Bongo gave his first public address via a video posted to social media since falling ill in October 2018 putting to rest any rumors he was dead.[11]

On 7 January 2019, soldiers in Gabon launched an unsuccessful coup d’etat attempt.[12]

On May 11, 2021, a Commonwealth delegation visited Gabon as Ali Bongo visited London to meet with the secretary general of the organization, which brings together 54 English-speaking countries. President Bongo expressed Gabon's willingness to join the Commonwealth.[13][14] In June 2022, Gabon joined the Commonwealth as its 55th member.[15]

In August 2023, following the announcement that Ali Bongo had won a third term in the general election, military officers announced that they had taken power in a coup d'état and cancelled the election results. They also dissolved state institutions including the Judiciary, Parliament and the constitutional assembly.[16][17] On 31 August 2023, army officers who seized power, ending the Bongo family's 55-year hold on power, named Gen Brice Oligui Nguema as the country's transitional leader.[18] On 4 September 2023, General Nguema was sworn in as interim president of Gabon.[19]

See also

References

- "History of Gabon - Lonely Planet Travel Information". www.lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 2020-07-24. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Gabon - History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Gabon Is Granted Sovereignty; Remains in French Community; Debre Hails the 11th African Republic Made Free Under Paris Accords in 1960". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Bongo's son appeals for calm as country goes into mourning" Archived 2019-01-08 at the Wayback Machine, Radio France Internationale, 9 June 2009.

- "Bongo's son to be Gabon candidate in August poll", AFP, 16 July 2009.

- "Unrest as dictator's son declared winner in Gabon", Associated Press, 3 September 2009.

- "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2016". www.state.gov. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- AfricaNews (5 December 2018). "Top govt officials visit 'recovering' Gabon president in Morocco". Africanews. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Gabon's Ali Bongo suffered a stroke, says vice-president". www.businesslive.co.za. Archived from the original on 2019-04-10. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- adekunle (10 December 2018). "President Ali Bongo of Gabon down with stroke". Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "'I am now fine': Ali Bongo tells Gabonese in New Year message". Africanews. January 1, 2019.

- "'Under control': Gabon foils coup attempt". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- "Gabon seeks to join Commonwealth - CHANNELAFRICA".

- https://www.marketwatch.com/press-release/gabon-expresses-intent-to-join-commonwealth-2021-05-11?mod=news_archive

- "Gabon and Togo join the Commonwealth". Commonwealth.

- "Gabon military officers claim power, say election lacked credibility". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- "Gabonese military officers announce they have seized power of oil-rich country". Reuters. 2023-08-30. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- "Gabon coup leaders name Gen Brice Oligui Nguema as new leader". BBC News. 31 August 2023.

- "Gabon coup leader Brice Nguema vows free elections - but no date". BBC News. 4 September 2023.

- Petringa, Maria (2006), Brazza, A Life for Africa.

- Schilling, Heinar (1937), Germanisches Leben, Koehler and Amelang, Leipzig, Germany.

Bibliography

- Chamberlin, Christopher. "The migration of the Fang into Central Gabon during the nineteenth century: a new interpretation." International Journal of African Historical Studies 11.3 (1978): 429-456. online

- Cinnamon, John M. "Missionary expertise, social science, and the uses of ethnographic knowledge in colonial Gabon." History in Africa 33 (2006): 413-432. online

- Digombe, Lazare, et al. "The development of an Early Iron Age prehistory in Gabon." Current Anthropology 29.1 (1988): 179-184.

- Gray, Christopher. "Who Does Historical Research in Gabon? Obstacles to the Development of a Scholarly Tradition1." History in Africa 21 (1994): 413-433.

- Gray, Christopher John. Colonial rule and crisis in Equatorial Africa: Southern Gabon, c. 1850-1940 (University Rochester Press, 2002). online

- Gray, Christopher J. "Cultivating citizenship through xenophobia in Gabon, 1960-1995." Africa today 45.3/4 (1998): 389-409 online

- Matsuura, Naoki. "Historical changes in land use and interethnic relations of the Babongo in southern Gabon." African Study Monographs 32.4 (2011): 157-176. online

- Ngolet, François. "Ideological manipulations and political longevity: the power of Omar Bongo in Gabon since 1967." African Studies Review 43.2 (2000): 55-71. online

- Nnang Ndong, Léon Modeste (2011). L'Effort de Guerre de l'Afrique: Le Gabon dans la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale, 1939-1947. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782296553903.

- Rich, Jeremy (2007). A Workman Is Worthy of His Meat: Food and Colonialism in the Gabon Estuary. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0741-7.

External links

- WWW-VL History Index of Gabon Archived 2023-06-24 at the Wayback Machine

- A detailed history (in French)

- Background Note: Gabon