Economy of South Africa

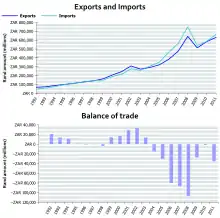

The economy of South Africa is the second largest in Africa (after Nigeria) and the most industrialized, technologically advanced, and diversified economy in Africa.[21] South Africa is an upper-middle-income economy, one of only eight such countries in Africa.[22] Following 1996, at the end of over twelve years of international sanctions, South Africa's nominal gross domestic product (GDP) almost tripled to a peak of US$416 billion in 2011. In the same period, foreign exchange reserves increased from US$3 billion to nearly US$50 billion, creating a diversified economy with a growing and sizable middle class, within two decades of ending apartheid.[23][24]

Johannesburg, the financial capital of South Africa | |

| Currency | South African rand (ZAR, R) |

|---|---|

| |

Trade organisations | AU, WTO, BRICS, AfCFTA, G-20, SACU and others |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | 60,14 million (2021 est.)[3] |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

| 6.9% (2022)[4] | |

Population below poverty line |

|

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Main industries | mining (world's largest producer of platinum group metals, gold, chromium), automobile manufacturing, metalworking, technology, machinery, textiles, iron and steel, IT, chemicals, fertilizer, foodstuffs, manufacturing, commercial ship repair. |

| External | |

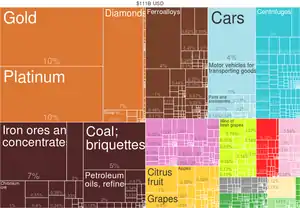

| Exports | $108 billion (2017)[14] |

Export goods | gold, diamonds, wines, iron ore, platinum, nonferrous metals, electronics, machinery and manufactured equipment, motor vehicles, fruits, various agricultural foodstuffs, ground and air military hardware. |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | $81.9 billion (2017)[14] |

Import goods | machinery and equipment, chemicals, petroleum products, scientific instruments, foodstuffs |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −4.4% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[16] | |

| Revenues | $122.49 billion (2022 est.) |

| Expenses | $139.28 billion (2022 est.) |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

Although the natural resource extraction industry remains one of the largest in the country with an annual contribution to the GDP of US$13.5 billion,[25] the economy of South Africa has diversified since the end of apartheid, particularly towards services. In 2019, the financial industry contributed US$41.4 billion to South Africa's GDP.[26] In 2021, South Africa-based financial institutions managed more than US$1.41 trillion in assets.[27] The total market capitalization of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange is US$1.28 trillion as of October 2021.[28]

The state-owned enterprises of South Africa play a significant role in the country's economy, with the government owning a share in around 700 SOEs involved in a wide array of important industries. In 2016 according to business executives, the top five challenges to doing business in the country were inefficient government bureaucracy, restrictive labour regulations, a shortage of skilled workers for some high-tech industries, political instability, and corruption. On the other hand, the country's banking sector was rated as a strongly positive feature of the economy.[29][30] The nation is among the G20, and is the only African country that is a permanent member of the group.[31]

History

The formal economy of South Africa has its beginnings in the arrival of Dutch settlers in 1652, originally sent by the Dutch East India Company to establish a provisioning station for passing ships. As the colony increased in size, with the arrival of Huguenots and German colonists, some of the colonists were set free to pursue commercial farming, leading to the dominance of agriculture in the economy.

At the end of the 18th century, the British annexed the colony. This led to the Great Trek, spreading farming deeper into the mainland, as well as the establishment of the independent Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State.[32]

In 1870 diamonds were discovered in Kimberley, while in 1886 some of the world's largest gold deposits were discovered in the Witwatersrand region of Transvaal, quickly transforming the economy into a resource-dominated one. The British annexed the area as a result of the Second Boer War which saw the deployment of scorched earth tactics against Boer non-combatants. South Africa also entered a period of industrialization during this time, including the organization of the first South African trade unions.[33]

The country soon started putting laws distinguishing between different races in place. In 1948 the National Party won the national elections, and immediately started implementing an even stricter race-based policy named Apartheid, in an attempt to shelter the original white society from a never-ending increase in the black population. The policy was widely criticised and led to crippling sanctions being placed against the country in the 1980s.[34]

South Africa held its first non-restricted racial elections in 1994, leaving the newly all-African elected African National Congress (ANC) government the daunting task of trying to restore order to an economy harmed by sanctions, while also integrating the previously disadvantaged segment of the population into it.

The government refrained from resorting to economic populism. Inflation was brought down, public finances were stabilised, and some foreign capital was attracted.[35] However, growth was still subpar.[35] At the start of 2000, then President Thabo Mbeki vowed to promote economic growth and foreign investment by relaxing restrictive labour laws, stepping up the pace of privatisation, raising governmental spending[36] and cutting interest rates sharply from 1998 levels.[37][38] His policies faced strong opposition from organised labour. From 2004 onward economic growth picked up significantly; both employment and capital formation increased.[35]

In April 2009, amid fears that South Africa would soon join much of the rest of the world in the late-2000s recession, Reserve Bank Governor Tito Mboweni and Minister of Finance Trevor Manuel differed on the matter: whereas Manuel foresaw a quarter of economic growth, Mboweni predicted further decline: "technically," he said, "that's a recession."[39] In 2009 the Nobel-Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz warned South Africa that inflation targeting should be a secondary concern amid the global financial crisis of 2007–2009.[40]

South Africa, unlike other emerging markets, has struggled through the late 2000s recession, and the recovery has been largely led by private and public consumption growth, while export volumes and private investment have yet to fully recover.[41] The long-term potential growth rate of South Africa under the current policy environment has been estimated at 3.5%.[42] Per capita GDP growth has proved mediocre, though improving, growing by 1.6% a year from 1994 to 2009, and by 2.2% over the 2000–09 decade,[43] compared to world growth of 3.1% over the same period.

The high levels of unemployment, at over 25%, and inequality are considered by the government and most South Africans to be the most salient economic problems facing the country.[44] These issues, and others linked to them such as crime, have in turn hurt investment and growth, consequently having a negative feedback effect on employment.[44] Crime is considered a major or very severe constraint on investment by 30% of enterprises in South Africa, putting crime among the four most frequently mentioned constraints.[45]

In April 2017, political tensions in the country arose over the sacking of nine cabinet members including Minister of Finance Pravin Gordhan by the president Jacob Zuma.[46] The finance minister was seen as central to efforts to restore confidence in South Africa. As a result of the tensions, S&P Global cut South Africa's credit rating to junk status on Monday 3 April 2017.[47] Fitch Ratings followed suit on Friday 7 April 2017 and cut the country's credit status to the sub-investment grade of BBB-.[48] The South African rand lost more than 11% in the week following the cabinet reshuffling.[47]

Historical statistics 1980–2022

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2022. Inflation under 5% is in green.[49]

| Year | GDP (in bn. US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$PPP) |

GDP

(in billion US$ nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in Percent) |

Unemployment (in Percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 148.6 | 5,110 | 89.4 | 3,075 | 9.2% | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | |||||||

| 1982 | n/a | |||||||

| 1983 | n/a | |||||||

| 1984 | n/a | |||||||

| 1985 | n/a | |||||||

| 1986 | n/a | |||||||

| 1987 | n/a | |||||||

| 1988 | n/a | |||||||

| 1989 | n/a | |||||||

| 1990 | n/a | |||||||

| 1991 | n/a | |||||||

| 1992 | n/a | |||||||

| 1993 | n/a | |||||||

| 1994 | n/a | |||||||

| 1995 | n/a | |||||||

| 1996 | n/a | |||||||

| 1997 | n/a | |||||||

| 1998 | n/a | |||||||

| 1999 | n/a | |||||||

| 2000 | 37.9% | |||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 |

This is a chart of the trend of South Africa's gross domestic product (GDP) at market prices estimated by the International Monetary Fund:[50]

| Year | GDP, US$ bln | US dollar exchange in early January | Unemployment rate | Per capita income, in US$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 80.547 | 0.8267 Rand[51] | 9.2 | 2764 |

| 1985 | 57.273 | 2.0052 Rand[51] | 15.5 | 1736 |

| 1990 | 111.998 | 2.5419 Rand[51] | 16.0 | 3039 |

| 1995 | 151.117 | 3.5486 Rand[51] | 16.7 | 3684 |

| 2000 | 132.964 | 6.1188 Rand[51] | 25.6 | 2986 |

| 2005 | 246.956 | 5.6497 Rand[51] | 26.7 | 5267 |

| 2010 | 363.655 | 7.462 Rand[52] | 24.9 | 7274 |

| 2015 | 510.937 | 15.52 Rand[53] | 22.8 | 5744[54] |

Sectors

South Africa has a comparative advantage in the production of agriculture, mining and manufacturing products relating to these sectors.[55] South Africa has shifted from a primary and secondary economy in the mid-twentieth century to an economy driven primarily by the tertiary sector in the present day which accounts for an estimated 65% of GDP or $230 billion in nominal GDP terms. The country's economy is reasonably diversified with key economic sectors including mining, agriculture and fisheries, vehicle manufacturing and assembly, food processing, clothing and textiles, telecommunication, energy, financial and business services, real estate, tourism, manufacturing, IT, transportation, and wholesale and retail trade.[56]

| Industry | Value added (R billion, 2004 prices) |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 43.382 |

| Mining and quarrying | 97.096 |

| Manufacturing (incl Space industry) | 296.586 |

| Electricity, gas and water | 33.951 |

| Construction | 59.943 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants | 246.584 |

| Transport, storage and communication | 178.591 |

| Finance, real estate and business services | 422.850 |

| General government services | 271.209 |

| Personal services | 107.690 |

| Taxes less subsidies on products | 215.668 |

| GDP at market prices | 1,973.552 |

Natural resources

In 2019, the country was the world's largest producer of platinum;[58] the world's largest producer of chromium;[59] the world's largest producer of manganese;[60] the 2nd largest world producer of titanium;[61] the world's 11th largest producer of gold;[62] the 3rd worldwide producer of vanadium;[63] the 6th largest world producer of iron ore;[64] the 11th largest world producer of cobalt;[65] and the 15th largest world producer of phosphate.[66] It was the world's 12th largest producer of uranium in 2018.[67]

Mining has been the main driving force behind the history and development of Africa's most advanced economy. Large-scale and profitable mining started with the discovery of a diamond on the banks of the Orange River in 1867 by Erasmus Jacobs and the subsequent discovery and exploitation of the Kimberley pipes a few years later. Gold rushes to Pilgrim's Rest and Barberton were precursors to the biggest discovery of all, the Main Reef/Main Reef Leader on Gerhardus Oosthuizen's farm Langlaagte, Portion C, in 1886, the Witwatersrand Gold Rush and the subsequent rapid development of the goldfield there, the biggest of them all.

South Africa is one of the world's leading mining and mineral-processing countries.[68] Though mining's contribution to the national GDP has fallen from 21% in 1970 to 6% in 2011, it still represents almost 60% of exports.[69] The mining sector accounts for up to 9% of value added.[70]

In 2008, South Africa's estimated share of world platinum production amounted to 77%; kyanite and other materials, 55%; chromium, 45%; palladium, 39%; vermiculite, 39%; vanadium, 38%; zirconium, 30%; manganese, 21%; rutile, 20%; ilmenite, 19%; gold, 11%; fluorspar, 6%; aluminium, 2%; antimony, 2%; iron ore, 2%; nickel, 2%; and phosphate rock, 1%.[68] South Africa also accounted for nearly 5% of the world's polished diamond production by value.[68] The country's estimated share of world reserves of platinum group metals amounted to 89%; hafnium, 46%; zirconium, 27%; vanadium, 23%; manganese, 19%; rutile, 18%; fluorspar, 18%; gold, 13%; phosphate rock, 10%; ilmenite, 9%; and nickel, 5%.[68] It is also the world's third largest coal exporter.[71]

The mining sector has a mix of privately owned and state-controlled mines, the latter including African Exploration Mining and Finance Corporation.[72]

Agriculture and food processing

In 2018, South Africa produced 19.3 million tonnes of sugarcane (14th largest producer in the world), 12.5 million tonnes of maize (12th largest producer in the world) 1.9 million tons of grape (11th largest producer in the world), 1.7 million tons of orange (11th largest producer in the world) and 397 thousand tons of pear (7th largest producer in the world). In addition, in the same year, it produced 2.4 million tons of potato, 1.8 million tons of wheat, 1.5 million tons of soy, 862 thousand tons of sunflower seed, 829 thousand tons of apple, 726 thousand tons of onion, 537 thousand tons of tomato, 474 thousand tons of lemon, 445 thousand tons of grapefruit, 444 thousand tons of banana, 421 thousand tons of barley, in addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products, such as avocado, pineapple, peach, tangerine, pumpkin, cabbage, carrot, rapeseed, sorghum etc.[73]

The agricultural industry contributes around 5% of formal employment, relatively low compared to other parts of Africa, as well as providing work for casual labourers and contributing around 2.8% of GDP for the nation.[5][74] However, due to the aridity of the land, only 13.5% can be used for crop production, and only 3% is considered high potential land.[75] The sector continues to face problems, with increased foreign competition and crime being two of the major challenges for the industry. The government has been accused of either putting in too much effort,[76] or not enough effort,[77] to tackle the problem of farm attacks as opposed to other forms of violent crime.

Maize production, which contributes to a 36% majority of the gross value of South Africa's field crops, has also experienced negative effects due to climate change.[78] The estimated value of loss, which takes into consideration scenarios with and without the carbon dioxide fertilization effect,[79] ranges between tens and hundreds of millions of Rands.[80]

According to FAOSTAT, South Africa is one of world's largest producers of: chicory roots (4th); grapefruit (4th); cereals (5th); green maize and maize (7th); castor oil seed (9th); pears (9th); sisal (10th); fibre crops (10th).[81] In the first quarter of 2010, the agricultural sector earned export revenues for R10.1 billion and used R8.4 billion to pay for imported agricultural products, therefore earning a positive trade balance of R1.7 billion.[82]

The most important agricultural exports of South Africa include: edible fruit and nuts, beverages, preserved food, tobacco, cereals, wool not carded or combed, miscellaneous food, sugar, meat, milling products, malt and starch.[82] These products accounted for over 80% of agricultural export revenue in the first quarter of 2010.[82] The most important agricultural imports, which accounted for over 60% of agricultural import value during the same period, include: cereals, meat, soya-bean oil cake, beverages, soya-bean oil and its fractions, tobacco, palm oil and its fractions, miscellaneous food, spices, coffee, tea, and preserved food.[82]

The dairy industry consists of around 4,300 milk producers providing employment for 60,000 farm workers and contributing to the livelihoods of around 40,000 others.[83]

The food sub-sector is the largest employer within the agro-processing sector – contributing 1.4% to total employment, and 11.5% within the manufacturing sector.[84] In 2006, the agro-processing sector represented 24.7% of the total manufacturing output.[84] Although the economy as a whole gained 975,941 jobs between 1995 and 2006, the agro-processing sector lost 45,977 jobs.[84] The competitive pressures from abroad, particularly from China and India, played a role in the decline of exports for the food, textiles and paper sub-sectors, as firms in these sectors increasingly compete with lower cost producers.[84] Increased exports from the beverages, tobacco, wood and leather sub-sectors over the period are probably due to the presence of large dominant firms within these sectors in South Africa, that have managed to remain competitive.[84]

Manufacturing

The manufacturing industry's contribution to the economy is relatively small, providing just 13.3% of jobs and 15% of GDP. There are growing sectors of manufacturing, however, such as in the Space industry. Labour costs are low, but not nearly as low as in most other emerging markets, and the cost of the transport, communications and general living is much higher.[85]

The South African automotive industry accounts for about 10% of South Africa's manufacturing exports, contributes 7.5% to the country's GDP and employs around 36,000 people. Annual production in 2007 was 535,000 vehicles, out of a global production of 73 million units in the same year. Vehicle exports were in the region of 170,000 units in 2007, exported mainly to Japan (about 29% of the value of total exports), Australia (20%), the UK (12%) and the US (11%). South Africa also exported ZAR 30.3 billion worth of auto components in 2006.[86]

BMW, Ford, Volkswagen, Daimler-Chrysler, General Motors, Nissan and Toyota all have production plants in South Africa. Large component manufacturers with bases in the country are Arvin Exhaust, Bloxwitch, Corning and Senior Flexonics. There are also about 200 automotive component manufacturers in South Africa, and more than 150 others that supply the industry on a non-exclusive basis. The industry is concentrated in two provinces, the Eastern Cape and Gauteng.[86] Companies producing in South Africa can take advantage of the low production costs and the access to new markets as a result of trade agreements with the European Union and the Southern African Development Community.[86]

After a steep decline of 10.4% in 2009, the manufacturing sector performed well in 2010, growing by 5%, though this rebound was primarily limited to the automotive, basic chemicals, iron and steel and food and beverages industries.[87] The performance of this sector remains curtailed by the low demand in South Africa's main export markets in the developed world.[87] There is growth in some areas, such as the Space industry in South Africa, which is expected to see an increase in Space industry jobs, and jobs in supporting technology and manufacturing sectors.

Service industry

Tourism

Telecommunications

The domestic telecommunications infrastructure provides modern and efficient service to urban and rural areas. This includes cellular and internet services from 5G to Gigabit Broadband.

In 1997, Telkom, the South African telecommunications parastatal, was partly privatised and entered into a strategic equity partnership with a consortium of SBC (AT&T), in exchange for a monopoly to provide certain services for 5 years. Telkom assumed an obligation to facilitate network modernisation and expansion into the unserved areas. A Second Network Operator, Neotel was to be licensed to compete with Telkom across its spectrum of services in 2002. Licensing officially began in late 2005.

Five mobile-phone companies provide service to over 50 million subscribers, with South Africa considered to have the 4th most advanced mobile telecommunications network worldwide. The five major cellular providers are Vodacom, MTN, Cell C(Vodacom), Telkom Mobile(8.ta) and Rain, with Neotel owned by Liquid Telecoms not offering mobile service anymore.

South African companies which provide services related to the Space industry, also increasing, and with the correct government legislation and support, this sector is expected to grow in South Africa.

Business process outsourcing

Over the last few decades, South Africa and particularly the Cape Town region has established itself as a successful call centre and business process outsourcing destination. With a highly talented pool of productive labour and with Cape Town sharing cultural affinity with Britain, large overseas firms such as Lufthansa, Amazon.com, ASDA, The Carphone Warehouse, Delta Airlines and many more have established inbound call centres within Cape Town as a means of utilising Cape Town's low labour costs and talented labour force.[88]

Tourism

South Africa is a popular tourist destination, with around 860,000 arrivals per month (March 2008) of which around 210,000 is from outside the African continent.[89] In 2012 South Africa received 9.2 million international arrivals.[90] In August 2017 3.5 million travellers came to South Africa.[91] According to the World Travel & Tourism Council, travel and tourism directly contributed ZAR102 billion to South African GDP in 2012 and supports 10.3% of jobs in the country.[92] Among the main attractions are the diverse and picturesque landscape, the game reserves and the highly regarded local wines.

The country's borders were reopened on 1 October 2020, with some exceptions to tourists travelling from specific European countries and the US, due to high levels of COVID-19 activity taking place there.

Financial services

.jpg.webp)

South Africa has a sophisticated financial structure, with the JSE Limited, the largest stock exchange on the African continent, ranking 17th in the world in terms of total market capitalisation, which is $1,005 Trillion as of August 2020.[93][94]

The banking industry, overseen by the South African Reserve Bank, is dominated by four local players: Nedbank, ABSA, Standard Bank and First Rand.[95] These banks provide both retail and investment banking services as the sector has become highly competitive with the re-entry of many experienced foreign banks, which returned to the market in the mid-1990s, having left in the late 1980s.[95] Banks operating in South Africa, when left short of liquidity, need to borrow from the SARB at a fluctuating repo rate, which, in turn, allows the central bank to monitor liquidity positions.[95]

Informal sector

South Africa's informal sector contributes 8% of the country's GDP and supports 27% of all working people. The South African Local Economic Development Network values the informal economy at 28% of SA's GDP.[96] Given the relevance of this input, there is a constant interest in developing actions on an inclusive urban planning for the working poor.[97]

Trade and investment

Principal international trading partners of South Africa—besides other African countries—include Germany, the United States, China, Japan, the United Kingdom, Bangladesh and Spain.[98] Chief exports include corn, diamonds, fruits, gold, metals and minerals, sugar, and wool. Machinery and transportation equipment make up more than one-third of the value of the country's imports. Other imports include chemicals, manufactured goods, and petroleum.

As a result of a November 1993 bilateral agreement, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) can assist US investors in the South African market with services such as political risk insurance and loans and loan guarantees. In July 1996, the US and South Africa signed an investment fund protocol for a $120 million OPIC fund to make equity investments in South and Southern Africa. OPIC is establishing an additional fund – the Sub-Saharan Africa Infrastructure Fund, capitalised at $350 million – to investment in infrastructure projects. The Trade and Development Agency also has been actively involved in funding feasibility studies and identifying investment opportunities in South Africa for U.S. businesses.

Despite the numerous positive economic achievements since 1994, South Africa has struggled to attract significant foreign direct investment. The situation may have started to change however, with 2005 seeing the largest single FDI into South Africa when Barclays bought a majority share in local bank Absa Group Limited. Deals between the British-based Vodafone and South Africa's Vodacom have taken place in 2006. In 2010, two multibillion-dollar deals, one by HSBC to acquire Nedbank and one by Walmart to acquire Massmart Holdings, fell through. (Walmart did buy Massmart in 2011)

Land reform and property rights

Nationalisation of mines debate

South Africa has been riven by arguments over whether the state should take over mineral resources.[99] A study commissioned by the African National Congress recommended against the policy, saying nationalisation would be an "economic disaster."[99] However, the ANC Youth Employment supporters disagree and state that it will give the government direct control over the mining sector which is also in alignment with the Freedom Charter signed in 1995.[100]

Land redistribution

The government aimed to transfer 30% of the 82 million hectares estimated to be in the hands of white farmers by Gugile Nkwinti, Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform, amounting to 24.5 million hectares, to black farmers by 2014. 6.7 million hectares had been transferred by early 2012 via redistribution and restitution.[101]

The land reform program has been criticised both by farmers' groups and by landless workers, the latter alleging that the pace of change has not been fast enough, and the former alleging anti white racist treatment with threats of genocide, voiced openly on multiple occasions by the ANC, including the former president Zuma, and expressing concerns that a similar situation to Zimbabwe's land reform policy may develop,[102] a fear exacerbated by comments made by former deputy president Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka.[103][104]

Labour market

South Africa has an extreme and persistent high unemployment rate of over 30%, which interacts with other socioeconomic problems such as: inadequate education, poor health and high levels of crime.[105] The poorest have limited access to economic opportunities and basic services.[106] According to a 2013 Goldman Sachs report, that number increases to 35% when including people who have given up looking for work.[23] A quarter of South Africans live on less than US$1.25 a day.[107]

South Africa's mass unemployment dates back to the 1970s, and continued to rise throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[108] Unemployment has increased substantially since the African National Congress came to power in 1994, increasing from 15.6% in 1995 to 30.3% in 2001.[109] In the second quarter of 2010, the jobless rate increased to 25.3%, and the number of people with work fell by 61,000 to 12,700,000. The biggest decline in employment was recorded in the manufacturing industry, which lost 53,000 jobs. Agriculture lost 32,000 jobs, employment in the construction industry fell by 15,000.[110] In the third quarter of 2010, 29.80% of blacks were recorded as unemployed, compared with 22.30% of Coloureds, 8.60 of Asians and 5.10% of Whites.[111]

The official unemployment rate, though very high by international standards, understates its magnitude because it includes only adults who are actively looking for work. Therefore, excluding those who have given up looking for employment.[112] Only 41% of the population of working age have any kind of job (formal or informal).[112] This rate is 30% points lower than that of China, and about 25% lower than that of Brazil or Indonesia.[112] The relatively generous social grants reduces the political cost of unemployment.[113] There is some evidence that households view paid employment and social grants as substitutes at the margin: households that lose a pension-eligible member subsequently report increased labour force participation.[113]

The unemployment problem is characterised by its lengthy duration. In the mid-1990s, nearly two-thirds of unemployed people had never worked for a salary.[108] The 2005 Labour Force Survey found that 40% of unemployed individuals have been unemployed for more than three years, while 59% had never had a job at all.[108] The unemployment rate has fuelled crime, inequality and social unrest. The global economic downturn made the problem worse, wiping out more than one million jobs. In September 2010, over one-third of South Africa's workforce were out of work, and so were more than half of blacks aged 15–34, three times the level than Whites.[114]

Some experts contend that higher wages negotiated by politically powerful trade unions have suppressed job growth.[114] According to a study by Dani Rodrik, the shrinkage of the non-mineral tradable sector since the early-1990s and the weakness of the export-oriented manufacturing were more to blame for the low level of employment.[115]

The government, however, tries putting measures in place to create employment in South Africa Archived 6 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine. On 5 March 2022, The department of home affairs announced that it was starting to recruit 10,000 youths to digitise its paper system.[116]

Knowledge

There has been a large degree of human capital flight from South Africa in recent years.[117][118] South Africa's Bureau of Statistics estimates that between 1 million and 1.6 million people in skilled, professional, and managerial occupations have emigrated overseas between 1994 and 2004 and that, for every emigrant, 10 unskilled people lose their jobs.[117] There are a range of causes cited for the migration of skilled South Africans.

In mid-1998, the Southern African Migration Project (SAMP) undertook a study to examine and assess the range of factors that contribute to skilled South Africans’ desire to leave the country: over two-thirds of the sample said that they had given the idea of emigration some thought while 38% said they had given it a "great deal of thought". Among the reasons cited for wishing to leave the country was the declining quality of life and high levels of crime. Furthermore, the government's affirmative action policy was identified as another factor influencing the emigration of skilled White South Africans. The results of the survey indicate that skilled Whites are strongly opposed to this policy and the arguments advanced in support of it, due to the negative impact it has had on South Africa.[118]

However, flight of human capital in South Africa should not be attributed solely to regional factors. For example, the demand for skilled labourers in the UK, US, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia has led to active recruitment programs by those countries in South Africa. These countries accounted for 75% (by volume) of recent skilled emigration with the UK receiving approximately half of annual skilled South African emigration from 1990 to 1996.[118] It has been suggested that the role of domestic socio-political variables may be negligible.[118] The health sector has been hit particularly hard.[119]

A widespread skills drain in South Africa and in the developing world in general is generally considered to be a cause for concern.[120]

For the medical sector, the loss of returns from investment for all doctors emigrating is $1.41bn for South Africa. The benefit to destination countries is huge: $2.7bn for the United Kingdom alone.[121]

In a case of reverse brain drain a net 359,000 high-skilled South Africans have returned to South Africa from foreign work assignments over a five-year period from 2008 to 2013. This was catalysed by the global financial crisis of 2007–8 and perceptions of higher quality of life in South Africa relative to the countries from which they first emigrated to. It is estimated that around 37% of those returning are professionals such as lawyers, doctors, engineers and accountants.[122]

Immigration

Refugees from poorer neighbouring countries include many immigrants from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi and others, representing a large portion of the informal sector. With high unemployment levels amongst poorer South Africans, xenophobia is prevalent and many South Africans feel resentful of immigrants who are seen to be depriving the native population of jobs, a feeling which has been given credibility by the fact that many South African employers have employed migrants from other countries for lower pay than South African citizens, especially in the construction, tourism, agriculture and domestic service industries. Illegal immigrants are also heavily involved in informal trading.[123] However, many immigrants to South Africa continue to live in poor conditions, and the South African immigration policy has become increasingly restrictive since 1994.[124]

Trade unions

Since 2007 the South African unions representing public sector workers recurrently went on strike, demanding pay rises significantly above inflation, in a practice that some experts argue is suppressing job growth, harming millions of South Africans who are out of a job.[114]

In August and September 2010, South African unions organised a crippling four-week national strike involving 1.3 million public sector workers, demanding an 8.6% wage increase. The strike ended after the government had raised its 5.2% wage increase to 7.5%. The deal swelled state spending by about 1%.[125]

Protesters sought to block hospitals, and South African media have reported numerous acts of violence against health and education staff who insisted on going to work. Volunteers and army medics were called in to help at hospitals, and some patients were moved to private medical facilities.[125]

There is a persistent wage differential between unionised and non-unionised workers in South Africa, suggesting that unions are keeping wages higher for their members, thereby posing additional challenges to the unemployment problem.[109]

In July 2014, amidst a national strike by 220,000 metalworkers, General Motors temporarily shut down its vehicle assembly plant, frustrating its plans to build 50,000 cars a year in the country. "The ongoing labour disruptions are harming the South African economy and are affecting the country's image around the globe," the company said in a statement at the time.[126]

Black Economic Empowerment

The end of apartheid in 1994 left behind a skewed racial economic hierarchy that placed minority whites at the top. Since then, the African National Congress government created the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) policy, designed to increase the participation of blacks, Coloreds, and Indians in the economy. However, BEE has faced criticism for not doing enough to accomplish this goal and only benefiting a small number of people to a great extent. This was acknowledged in 2010 by Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe, at the first meeting of the BEE Advisory Council, when he said, "The story of black economic empowerment in the last 15 years has been a story dominated by a few individuals benefiting a lot." A 2010 report from the OECD concluded that the "relative improvement in poverty levels," since the end of apartheid, has actually been driven by social assistance grants and not the labour market.[127]

As of 2014, roughly ten percent of the Top 100 companies on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange were directly held by black investors through Black Economic Empowerment schemes. Black Economic Empowerment policies have been credited with creating a class of Black South Africans with a level of wealth on the same order of magnitude as very rich White South Africans.[24]: 2

Black Economic Empowerment—its purpose the "economic empowerment of all black people, including women, workers, youth, people with disabilities and people living in rural areas"—requires the Minister of Trade and Industry to develop and publish Codes of Good Practice, aimed at setting guidelines for the process of BEE in the whole economy.[128] A scorecard is used by the department to measure compliance with the BEE requirements, and is used for public procurement, public-private partnerships, sale of state-owned enterprises, when licenses are applied for, and for any other relevant economic activity.[128]

The government's Black Economic Empowerment policies have drawn criticism from the Development Bank of Southern Africa for focusing "almost exclusively on promoting individual ownership by black people (which) does little to address broader economic disparities, though the rich may become more diverse." The System has also been criticised for placing lesser educated people in more important positions in the workplace and their failure to perform to the standards required has had an immense impact on the economy. Another criticism also includes that the system goes against the constitution's preaching of equality by having preference over people, not on merit, but for their skin colour and is considered the opposite of what many people fought for during the Apartheid era.[129] Official affirmative action policies have seen a rise in black economic wealth and an emerging black middle class.[130] An increasing number of black candidates who are supposed to be beneficiaries of affirmative action are dissociating themselves from it, largely because of the perception that the appointments are not based on merit.[131] The policy has also been criticised for having a negative impact on employment levels as it is viewed as being more of an additional burden for employees than as a transformative agent for the unemployed.[24]: 2 Particularity in an economy where a major cause of inequality has been a growing disparity of income within the majority black population divided along lines of employment.[24]: 12

Gender Equality

South Africans in general, regardless of race, hold what would be considered "traditional" stances on gender roles for men and women. The majority of the workforce is composed of males, while the majority of women do not participate.[132] This viewpoint on males as "breadwinners" is very much in line with traditional African values across the continent. Additionally, females face a problem in terms of earnings, with 77% of women earning the same as their male counterparts.[133] However, more women are becoming part of the agricultural workforce (55%) as of 2012, marking a move towards modernisation for women's participation in the economy.[134]

South African legislation is strongly geared to promoting gender equality in the workplace. This is characterised by several comprehensive government programs and organisations that provide resources and services to females, both adult and adolescent. Such initiatives include the Employment Equity Act, No. 55 of 1988 (aimed at promoting women's participation in mainly private sector jobs).[135] UNFPA South Africa is one such promoter of these policies and programs.[136] Internally, the South African government has founded the Commission for Gender Equality.[137] The commissions main focus is on securing adequate education and job training for women who are disenfranchised or otherwise at a disadvantage when attempting to enter the workforce.

Not uncommon in Africa, gender equality seems to be a very cogent problem in the South African workforce. According to Bain & Company, around 31% of companies have no form of female leadership, either in management or executive positions.[138] 22% of board directors are women, however, only 7% were designated as "executives", lower than the global average of 12%.[139] Additionally, the eNPE (Employee Net Promoter Score) for women is a net negative (- 4) as compared to men (8), according to a survey conducted of 1000 participants.[140] This indicated a low level of actual economic promotion for women, despite public and international initiative towards the contrary.

Infrastructure

Energy

Scheduled rolling blackouts are a part of daily life. Electricity theft is widespread. After years of sub-standard maintenance and the South African government's inability to manage strategic resources, the state-owned power supplier Eskom started experiencing deficiency in capacity in the electrical generating and reticulation infrastructure in 2007. Such lack led to inability to meet the routine demands of industry and consumers, resulting in countrywide rolling blackouts. Initially, the lack of capacity was triggered by a failure at Koeberg nuclear power station, but a general lack of capacity due to increased demand and lack of government planning soon came to light. The supplier and the South African government has been widely criticised for failing to adequately plan for and construct sufficient electrical generating capacity,[141] although ultimately the government has admitted that it was at fault for refusing to approve funding for investment in infrastructure.[142]

The margin between national demand and available capacity is still low or negative (particularly in peak hours), and power stations are under strain, such that surges in demand, which are common during winter, or drops in supply, often a result of a lack of coal for power plants, result in another phase of rolling blackouts.[143] The government and Eskom are currently planning new power stations, at cost to the South African consumer. The power utility plans to have 20,000 megawatts of nuclear power in its grid by 2025.[144][145]

Water

Some predictions show surface water supply could decrease by 60% by the year 2070 in parts of the Western Cape.[146]

The South African government planned to spend R69 billion on water infrastructure between 2008 and 2015.[147] This involves building new dams and ancillary infrastructure, and repairing existing infrastructure.[147] South Africa has an estimated total water capacity of 38 billion cubic metres, but will need 65 billion by 2025 if the economy is to keep on growing.[147] The massive urban migration has placed further strain on the country's ageing water infrastructure and created a large backlog.[147]

Developments and Maintenance

As part of an international attempt to modernize infrastructure, South Africa has faced increasing pressure to invest government funds into its water and electricity sectors. At current, these sectors are underfunded by approximately US$464 billion (This is according to the G20 GI Hub).

Income levels

| Year | White | Coloured | Asian | Black |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1917 | 100 | 22.0 | 22.1 | 9.1 |

| 1924 | 100 | 20.0 | 19.4 | 7.9 |

| 1936 | 100 | 15.6 | 23.1 | 7.6 |

| 1946 | 100 | 16.3 | 23.0 | 8.9 |

| 1956 | 100 | 16.9 | 21.9 | 8.6 |

| 1960 | 100 | 15.9 | 17.1 | 8.1 |

| 1970 | 100 | 17.3 | 20.2 | 6.8 |

| 1975 | 100 | 19.4 | 25.4 | 8.6 |

| 1980 | 100 | 19.1 | 25.5 | 8.5 |

| 1987 | 100 | 20.9 | 30.2 | 8.5 |

| 1993 | 100 | 19.3 | 42.0 | 10.9 |

| 1995 | 100 | 20.0 | 48.4 | 13.5 |

| 2000 | 100 | 23.0 | 41.0 | 15.9 |

| 2008 | 100 | 22.0 | 60.0 | 13.0 |

| White | Coloured | Asian | Black | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | 0.37 | 0.38 | – | 0.43 | 0.51 |

| Urban | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.56 |

| Overall | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.59 |

South Africa has extreme differences in incomes and wealth.[106] The good level of economic growth in the post-apartheid period has led to a measurable decline in income poverty, but inequality has increased.[106] The high level of overall income inequality has further accentuated: the country's Gini coefficient increased by four percentage points, from 0.66 to 0.70, between 1993 and 2008, and income has become increasingly concentrated in the top decile.[148] Inequality between urban and rural areas is changing: while rural poverty rates remain substantially higher than those in urban areas, urban poverty rates are rising and rural rates seem to be falling.[148]

While between-race inequality is slowly falling, an increase in intra-race inequality is preventing the aggregate measures from declining. Despite that, between-race inequality remains a central issue: real incomes have been rising for all groups, but many blacks in the country still live in poverty. At any poverty line, blacks are very much poorer than coloureds, who are very much poorer than Indians, who are poorer than whites.[148][150] In 2002, according to one estimate, 62% of Black Africans, 29% of Coloureds, 11% of Asians, and 4% of Whites lived in poverty.[151][152]

The mean per-capita income has risen from R10,741 in 1993 to R24,409 in 2008, but these figures hide large differences in household welfare, both within and across population groups: the average Black income increased from R6,018 in 1993 to R9,718 in 2008; for Coloured households, the increase was from R7,498 to R25,269; for Whites, the increase was from R29,372 to R110,195.[153] While mean income rose about 130% from 1993 to 2008, the median income rose just 15% over the same period, from R4,444 to R5,096, indicating that the increases are being driven by a small number of very large incomes, especially for Whites.[153]

In 2000 the average white household was earning six times more than the average black household.[154] In 2004, 29.8% of all households had an income (at constant 2001 prices) of less than R9,600 per annum, while 10.3% of all households enjoyed an annual income (at constant 2001 prices) of more than R153,601 per annum.[155]

One study using calculations based on National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) data suggests that 47% of South Africans live below the poverty line: 56% of blacks live in poverty compared to 2% of whites, using an arbitrary income poverty line of R502 per capita.[156] Although, it should also be noted that black South Africans make up the majority of the population at 79.2% while white South Africans make up only 8.9% of the population according to the Statistics South Africa census released in 2011. The United Nations Development Program's Human Development Index (HDI) ranked South Africa 110 out of 169 countries in 2010. The report notes, however, that the region's assessment has improved slowly since 1980. The HDI includes a Human Poverty Index (HPI-1), which ranked South Africa 85 out of 135 countries.

The number of South Africans living below the poverty line, identified according to Apartheid-era social categories, was calculated in one study as 56% "black", 27% "coloured", 9% "Indian", and 2% "white".[156] In the past inequality in South Africa was largely defined along race lines, but it has become increasingly defined by inequality within population groups as the gap between rich and poor within each group has increased substantially.[157]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development proposals for addressing income inequality included: encouraging more saving and investment; a liberalisation of product-market regulation; easier access to credit for small businesses; greater co-ordination in wage bargaining; and measures to tackle the high level of youth unemployment. Some proposals have included wage subsidies for people being trained, a minimum wage differentiated by age, and extended periods of probation for young workers.[158] In post-Apartheid South Africa, only Asians have made significant strides in closing the income gap with Whites; while Coloured and Black South Africans have had much more muted progress. [159]

A 2011 study published by the University of Cape Town about the richest 10% found that nearly 40% are black, where this group had once been almost exclusively white.[160] While only 29% of the absolute wealthiest South Africans are black, this jumps to 50% among the "entry-level" rich (defined as earning more than $4,000 per month).[160] Factors that were found to be common among those in the entry-level rich group include being young, entrepreneurial and having some post-secondary education.[160]

According to one estimate, 10.4% of South Africans belonged to the "higher middle class" in 2004, defined as having a per capita income of over R40,000 (in 2000 Rand).[161]

Taxes and transfers

Taxation

The top rate of personal income tax rate in South Africa is 45%; the corporate tax rate is 27%.[162] Other taxes include a value-added tax and a capital gains tax, with the overall tax burden amounting to 23.4% of total domestic income.[162]

Social benefits

South Africa has about three times as many recipients of social benefits as it has income tax-payers, an extremely high ratio by international standards.[44] After 1994 resources have been rapidly reallocated to black households: while approximately 40% of aggregate social spending was directed to whites and 43% to blacks in the mid-1980s, by the late 1990s fully 80% of total social spending was assigned to blacks and less than 10% to whites.[163] At present, blacks contribute some 50% of total government transfers, while receiving roughly 80%.[164]

The Unemployment Insurance Fund is financed out of premiums, contributions and benefits depend on earnings, and focuses on insuring workers against the risk of income loss.[165]

Social assistance grants

Social assistance grants are non-contributory, income-tested benefits provided by the state to the poor, and are financed out of general tax revenues without any links between contributions and benefits.[165] They are provided in the form of: grants for older persons; disability grants; war veterans grants; care dependency grants; foster child grants; child support grants; grant-in-aid; social relief of distress.[166]

The state old age pension, received by over 80% of the elderly,[167] is a non-contributory pension and pays more than twice median per capita Black income, thus representing an important source of income for a third of all Black households in the country.[168] It pays a maximum of R1,780 (as of July 2019)[169] to people who reach pension age without access to private pensions.[168]

The child support grant provides R420 per month, per child (as of July 2019)[170] for every child in the household younger than 18,[170] and benefited 9.1 million children by April 2009.[167]

The war veterans grant is provided to former soldiers who fought in the Second World War or the Korean War, and pays a maximum amount of R1,800 per month (as of July 2019).[171]

Comparison with other emerging markets

According to a December 2010 article by the South African Government Communication and Information System's now-defunct BuaNews news service, South Africa was said to compare well to other emerging markets on affordability and availability of capital, financial market sophistication, business tax rates and infrastructure, but to fare poorly on the cost and availability of labour, education, and the use of technology and innovation.[172] South Africa does have expertise in the Space industry, and students learning more through the South African SEDS. With the correct government support, South Africa can increase the jobs in the manufacturing, testing, and analysis sectors of the growing Space industry.

Released in early December 2010 and no longer available online, the survey by Brazil's National Confederation of Industry, “Competitividade Brasil 2010: Comparaçao com Paises Selecionados“, (Competition Brazil: A comparison with selected countries), found South Africa to have the second most sophisticated financial market and the second-lowest effective business tax rate (business taxes as a percentage of company profits), out of 14 surveyed countries. The country was also ranked fourth for ease of accessing capital, fourth for cost of capital, sixth for its transport infrastructure (at the time considered better than that of China, India, Mexico, Brazil and Poland, but behind that of Korea and Chile), and seventh for foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP: in 2008 it was over 3% of the GDP.[172]

Nevertheless, South Africa is falling behind other emerging markets, such as India and China, owing to several factors: the country is relatively small, without the advantage of a huge domestic customer base; it has had for decades an unusually low rate of saving and investment, partly because of low disposable income; an inadequate education system results in an acute shortage of skilled manpower; a strong and volatile currency deters investors and makes its exports less competitive; the infrastructure, though far better than in the rest of Africa, suffers from severe bottlenecks, including scheduled power shortages, and urgently needs upgrading.[85]

In 2011, after a year of observer status, South Africa officially joined the BRICS group of now-five emerging-market nations at the summit held in Sanya, Hainan, China.[173]

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Mid-year population estimates July 2021" (PDF). statssa.gov.za. Statistics South Africa. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- "The World Factbook- South Africa". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Monthly share of people who are worried about poverty and social inequality in South Africa from January 2021 to November 2022". statista.com. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at $6.85 a day (2017 PPP) (% of population) - South Africa". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "South Africa Overview". World Bank. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- Nations, United. "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- "Labor force, total – South Africa". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- "South Africa's unemployment rate hits new record high in second quarter". Reuters. 24 August 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- "Ease of Doing Business in South Africa". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Top South African Trading Partners 2021". worldstopexports.com.

- "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "S&P upgrades South Africa's outlook to 'positive'". businesslive.co.za. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- "Rating Action: Moody's changes South Africa's outlook to stable; affirms Ba2 ratings". moodys.com. April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- "Fitch Revises South Africa's Outlook to Stable; Affirms at 'BB-'". fitchratings.com. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- "Scope downgrades South Africa's credit ratings to BB, revises Outlooks to Stable". scoperatings.com. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Government, National. "Why South Africa". InvestSA. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "South Africa since apartheid: Boom or bust? - CNN.com". CNN. 27 November 2013.

- Herbst, Jeffrey & Mills, Greg (2015). How South Africa Works: And Must Do Better. Pan Macmillan South Africa. ISBN 978-1-77010-408-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Statista – Mining Industry in South Africa".

- "South Africa: finance sector's value added to GDP from 2014 to 2020".

- "Topic: Financial Market in Africa".

- "Johannesburg Stock ExchangeL Market Data". 17 October 2021.

- "16 things businesses hate about South Africa". Business Tech. 16 October 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Economies". Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Wood, Catherine Grant Makokera and Christopher. "GEG Africa – South Africa and the G-20". gegafrica.org. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Great Trek | South African history | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Gentle, Leonard; Callinicos, Luli; Jansen, Martin; Nieftagodien, Noor; Jordi, Richard. A History of Trade Unionism In South Africa (PDF). South Africa. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-620-78227-2.

- Ap (21 October 1985). "COMMONWEALTH LEADERS AGREE ON SANCTIONS AGAINST SOUTH AFRICA". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- "Economic Assessment of South Africa 2008: Achieving Accelerated and Shared Growth for South Africa". OECD. Archived from the original on 9 August 2009.

- "SA government spending". data.worldbank.org/country/south-africa. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "SA real interest rate". data.worldbank.org/country/south-africa. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "South Africa inflation rate". data.worldbank.org/country/south-africa. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Quoted in Mafirakurewa 2009.

- Wessels, Leani (8 July 2009). "Stiglitz: SA must drop targets". News24.co.za. Archived from the original on 11 July 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- "South Africa: 2011 Article IV Consultation" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2014.

- "South Africa Economic Update, Focus on Savings, Investment, and Inclusive Growth" (PDF). World Bank. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2012.

- "OECD Economic Surveys – South Africa". OECD. July 2010. p. 36. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012.

- "OECD Economic Surveys – South Africa". OECD. July 2010. p. 38. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012.

- Stone, Christopher (August 2006). "Crime, Justice, and Growth in South Africa: Toward a Plausible Contribution from Criminal Justice to Economic Growth" (PDF). Center for International Development at Harvard University. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2011.

- "South Africa's Zuma accuses protesters of racism after marches". Reuters. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Cotterill, Joseph. "Zuma tries to reassure investors after South Africa's rating cut". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- "Junk for South Africa as Fitch Joins S&P in Cut on Politics". Bloomberg.com. 7 April 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". imf.org. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Historical exchange rates – South African Reserve Bank". Archived from the original on 31 March 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Exchange Rate Average (South African Rand, US Dollar) – X-Rates". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "XE Currency Table: ZAR – South African Rand". Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- "GDP per capita (current US$) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Competitiveness of selected South African agricultural products in the European union market" (PDF). Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2013.

- South Africa's Economy. "Key Sectors". Media Club South Africa. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- "Gross Domestic Product, First Quarter 2013" (PDF). StatsSA. 28 May 2013.

- "USGS Platinum Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Chromium Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Manganese Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Titanium Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Gold Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Vanadinum Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Iron Ore Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Cobalt Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Phosphate Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "World Uranium Mining". Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Yager, Thomas R. (September 2010). "The Mineral Industry of South Africa" (PDF). US Geological Survey. p. 37.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2012.

- "Nationalisation in South Africa: A debate that will persist". The Economist. 3 December 2011.

- "Results-Based Country Strategy Paper, 2008–2012" (PDF). African Development Bank. October 2009. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012.

- "South Africa's coal future looks bright".

- "AEMFC readies for second mine as losses mount". Mining MX. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- "South Africa production in 2018, by FAO".

- Human Rights Watch, 2001. Unequal Protection: The State Response to Violent Crime on South African Farms, ISBN 1-56432-263-7.

- Mohamed, Najma. 2000. "Greening Land and Agrarian Reform: A Case for Sustainable Agriculture", in At the Crossroads: Land and Agrarian Reform in South Africa into the 21st century, ed. Cousins, Ben. Bellville, School of Government, University of the Western Cape. ISBN 1-86808-467-1.

- Bronwen Manby (August 2001). Unequal Protection – The State Response to Violent Crime on South African Farms. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-263-0. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- Farms of Fear, The Sunday Times Magazine.

- http://www.gcis.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/resourcecentre/pocketguide/013_agriculture.pdf

- The CO2 fertilization effect: higher carbohydrate production and retention as biomass and seed yield. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- "Economic Impacts of Climate Changeon Agriculture and Implications for Food Security in Southern Africa" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- "FAOSTAT 2008 by Production". faostat.fao.org. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- "Competitiveness of selected South African agricultural products in the European union market" (PDF). Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2013.

- "Agriculture". South Africa Online. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 17 July 2006.

- "Asgisa And Economic Growth: Implications For Skills Development" (PDF). Department of Labour, South Africa. March 2008. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2014.

- "South Africa, Jobless growth – The Economist". The Economist.

- "Automotive in South Africa – Key information on the South African motor industry". MBendi.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Annual report 2010–2011". Department of Trade and Industry. p. 26. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013.

- Accelerator, Outsource. "Outsourcing to South Africa". Outsource Accelerator. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- "Monthly tourism statistics June 2008" (PDF). South African Tourism. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- "UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2013 edition" (PDF). UNWTO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "Monthly tourism statistics August 2017". Statistics South Africa. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2013 South Africa" (PDF). WTTC. March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "JSE Markets' Weekly Statistics 20200821". Market Statistics; JSE. 28 August 2018. Archived from the original (XLSX) on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- "USD to ZAR Exchange Rate". Bloomberg. 28 August 2020. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- "Doing business in South Africa" (PDF). Treasury Today. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2014.

- Greve, Natalie (26 April 2017). "Vital part of SA economy still being ignored". Fin24. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "Graduate Training. [Social Impact]. ICP. Inclusive Cities Project (2008–2014)". SIOR, Social Impact Open Repository. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- "South Africa". The World Factbook. CIA. 31 May 2022.

- Vernon Wessels; Carli Lourens (7 February 2012). "Anglo Says South Africa Must End Debate Over Nationalization". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014.

- Nattrass, Nicoli; Nattrass, Jill (October 1990). "South Africa, the homelands and rural development". Development Southern Africa. 7 (sup1): 517–534. doi:10.1080/03768359008439560. ISSN 0376-835X.

- Davies, Richard (1 March 2012). "Minister dissects government's land-reform target". BusinessDay. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012.

- South Africa's bitter harvest.

- South Africans' long wait for land, BBC News.

- SA 'to learn from' land seizures, BBC News.

- http://www.oecd.org/document/21/0,3343,en_2649_33733_45637781_1_1_1_1,00.html. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "South Africa: Country Brief". World Bank. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012.

- "- Human Development Reports". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- David Lam; Murray Leibbrandt; Cecil Mlatsheni (2008). "Education and Youth Unemployment in South Africa". Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit. p. 2. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012.

- Banerjee, Abhijit; Galiani, Sebastian; Levinsohn, Jim; McLaren, Zoë; Woolard, Ingrid (2008). "Why has unemployment risen in the New South Africa?". Economics of Transition. 16 (4): 715–740. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.514.4342. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0351.2008.00340.x. S2CID 33437467.

- Nasreen Seria (27 July 2010). "South Africa Sheds Jobs, Denting Economic Recovery". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Statistics South Africa – Economic Indicators for 2009–2010 by Year, Key Indicators and month

- "A Fresh Look at Unemployment". Centre for Development and Enterprise. July 2011. p. 2. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012.

- Rodrik, Dani (September 2006). "Understanding South Africa's Economic Puzzles" (PDF). John F. Kennedy School of Government. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2012.

- Dugger, Celia W. (27 September 2010). "Wage Laws Squeeze South Africa's Poor – NYTimes.com". The New York Times.

- "Understanding South Africa" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- "VACANCIES: Home Affairs is recruiting 10,000 unemployed South African youths – Work In South Africa". 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- Human Capital Flight: Stratification, Globalization, and the Challenges to Tertiary Education in Africa; Benno J. Ndulu; JHEA/RESA Vol. 2, No. 1, 2004, pp. 57–91

- "Labour migration" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Health Personnel in Southern Africa: Confronting maldistribution and brain drain Archived 30 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Paul Collier. "Africa's Exodus: Capital Flight and the Brain Drain as Portfolio Decisions". Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Mills EJ et coll.: The financial cost of doctors emigrating from sub-Saharan Africa: human capital analysis. British Medical Journal 2011.343.

- Hedley, Nick (14 January 2014). "Expertise flows back into SA as brain drain is reversed". Business Day. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "African Security Review Vol 5 No 4, 1996: Strategic Perspectives on Illegal Immigration into South Africa". Archived from the original on 19 October 2005.

- "Queens College: The Brain Gain: Skilled Migrants and Immigration Policy in Post-Apartheid South Africa". Archived from the original on 25 November 2005.

- David Smith (6 September 2010). "South African unions suspend public sector strike". the Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "South Africa arm of General Motors hit by wage strike shuts plant". South Africa News.Net. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "South Africa: Inequality not so black and white". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Rulof Burger; Rachel Jafta (March 2010). "Affirmative action in South Africa: an empirical assessment of the impact on labour market outcomes" (PDF). Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- Neva Makgetla, Inequality on scale found in SA bites like acid, Business Day, 31 March 2010

- "Black middle class boosts car sales in South Africa – Business – Mail & Guardian Online". Mg.co.za. 15 January 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- "Transformation Booklet" (PDF). Nedbank Group. p. 77. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2013.

- "Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15–64) (modeled ILO estimate)". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "South Africa falling short in gender equality standards". 4 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Africa, Statistics South. "Social welfare | Statistics South Africa". statssa.gov.za. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "The Status of Gender Equality in South Africa". CBE International. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "UNFPA South Africa | Gender Equality". southafrica.unfpa.org. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Patel, Leila. "South Africa's social welfare system faces deepening challenges". The Conversation. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Gender (Dis)parity in South Africa". 24 May 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Stats show gender inequality power positions in SA | Northglen News". Northglen News. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Join the fight against extreme poverty". ONE. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Power Failures Outrage South Africa" article by Barry Bearak and Celia W. Dugger in The New York Times 31 January 2008

- "S Africa cuts power to neighbours". BBC News. 21 January 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "Why South Africa's electricity blackouts are set to continue for the next five years". The Conversation. 30 March 2021.

- "Eskom reopens 3 power stations". News24. 14 February 2008. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- "Eskom mulls new power stations". Fin24. 18 September 2008. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- Climate change to create African 'water refugees' – scientists Archived 25 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters Alertnet. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- Geyde, Lloyd (2 March 2012). "How to keep SA's head above water". Mail & Guardian Online. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012.

- Leibbrandt, Murray; Woolard, Ingrid; Finn, Arden; Argent, Jonathan (2010). "Trends in South African Income Distribution and Poverty since the Fall of Apartheid". OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. doi:10.1787/5kmms0t7p1ms-en. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Murray Leibbrandt; Ingrid Woolard; Arden Finn; Jonathan Argent (20 January 2010). "Trends in South African Income Distribution and Poverty since the Fall of Apartheid" (PDF). OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 101. OECD Publishing. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Income Inequality in South Africa: Center for Global Studies at the University of Illinois Archived 8 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Marger, Martin N. (22 April 2008). Race and Ethnic Relations: American and Global Perspectives. ISBN 9780495504368. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "South Africa's Unemployment Rate Increases to 23.5%". Bloomberg. 5 May 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- Murray Leibbrandt; James Levinsohn. "Fifteen Years On: Household Incomes in South Africa" (PDF). University of Cape Town; Yale University; NBER. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2013.

- SARPN – South Africa Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine at sarpn.org.za

- South African Institute for Race Relations, South Africa Survey 2006/2007

- Gumede, Vusi. "Poverty, Inequality and Human Development in a Post-Apartheid SouthAfrica" (PDF). Conference paper presented at ‘Overcoming inequality and structural poverty in South Africa: Towards inclusive growth and development’, Johannesburg, 20–22 September 2010. Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- "SARPN – South Africa". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "South Africa's economy: How it could do even better". The Economist. 22 July 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- "Highest Level of Education Attainment in South Africa | LMI".

- Conway-Smith, Erin (17 October 2011). "Black South Africans moving up the wealth ladder". Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Trends in poverty and inequality since the political transition – Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers – 1/2005 Archived 19 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "South Africa Economy: Facts, Data, & Analysis on Economic Freedom". Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012.

- Kanbur, Ravi; Bhorat, Haroon (September 2005). "Poverty and Well-being in Post-Apartheid South Africa: An Overview of Data, Outcomes and Policy" (PDF). University of Cape Town; Cornell University. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2012.

- "Racial inequality and demographic change in South Africa". UNU-WIDER. 16 September 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Trends in South African Income Distribution and Poverty since the Fall of Apartheid". OECD. 28 May 2010. p. 47. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012.

- "You and Your Grants 2011/12" (PDF). South African Social Security Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2011.

- Murray Leibbrandt; James Levinsohn. "Fifteen Years On: Household Incomes in South Africa" (PDF). University of Cape Town; Yale University; NBER. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2013.

- Ardington, Cally; Case, Anne; Hosegood, Victoria (2009). "Labor Supply Responses to Large Social Transfers: Longitudinal Evidence from South Africa". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 1 (1): 22–48. doi:10.1257/app.1.1.22. PMC 2742429. PMID 19750139.

- "Old age pension | South African Government". gov.za. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- "Child support grant". South Africa Government Services.

- "War veterans grant". War veterans grant. South Africa Government Services.

- "SA fares well in emerging markets study". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Blanchard, Ben and Zhou Xin, reporting; Ken Wills, editing, "UPDATE 1-BRICS discussed global monetary reform, not yuan", Reuters Africa, 14 April 2011 9:03 am GMT. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

External links

- Economy of South Africa at Curlie

- South African Tax Resources

- South African Reserve Bank – Economic and Financial Data

- Statistics South Africa – Official Government Statistics

- OECD Economic Forecast Summary for South Africa

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics South Africa

- Tariffs applied by South Africa as provided by ITC's ITC Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements