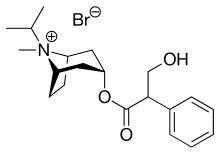

Ipratropium bromide

Ipratropium bromide, sold under the trade name Atrovent among others, is a type of anticholinergic (SAMA: short acting muscarinic antagonist) medication which opens up the medium and large airways in the lungs.[1][2] It is used to treat the symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma.[1] It is used by inhaler or nebulizer.[1] Onset of action is typically within 15 to 30 minutes and lasts for three to five hours.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Atrovent, Apovent, Ipraxa, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a618013 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Inhalation, nasal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 0 to 9% in vitro |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.040.779 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H30BrNO3 |

| Molar mass | 412.368 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include dry mouth, cough, and inflammation of the airways.[1] Potentially serious side effects include urinary retention, worsening spasms of the airways, and a severe allergic reaction.[1] It appears to be safe in pregnancy and breastfeeding.[1][3] Ipratropium is a short-acting muscarinic antagonist,[4] which works by causing smooth muscles to relax.[1]

Ipratropium bromide was patented in 1966, and approved for medical use in 1974.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medicines needed in a health system.[6] Ipratropium is available as a generic medication.[1] In 2020, it was the 312th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 900 thousand prescriptions.[7]

Medical uses

Ipratropium as an inhalant can be used for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma exacerbation.[8] It is supplied in a canister for use in an inhaler or in single dose vials for use in a nebulizer.[9]

It is also used to treat and prevent minor and moderate bronchial asthma, especially asthma that is accompanied by cardiovascular system diseases, as it has been shown to produce fewer cardiovascular side effects.[10]

Combination with beta-adrenergic agonists increases the dilating effect on the bronchi, as when ipratropium is combined with salbutamol (albuterol — USAN) under the trade names Combivent (a non-aerosol metered-dose inhaler or MDI) and Duoneb (nebulizer) for the management of COPD and asthma, and with fenoterol (trade names Duovent and Berodual N) for the management of asthma.

Ipratropium as a nasal solution sprayed into the nostrils can reduce rhinorrhea but will not help nasal congestion.[11]

Contraindications

The main contraindication for inhaled ipratropium is hypersensitivity to atropine and related substances.[12][13]

Peanut allergy

Previously Atrovent inhalers used chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) as a propellant and contained soy lecithin in the propellant ingredients. In 2008 all CFC inhalers were phased out and hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) inhalers replaced them. Allergy to peanuts was noted for the inhaler as a contraindication but now is not. It has never been a contraindication when administered as a nebulized solution.[14]

Side effects

If ipratropium is inhaled, side effects resembling those of other anticholinergics are minimal. However, dry mouth and sedation have been reported. Also, effects such as skin flushing, tachycardia, acute angle-closure glaucoma, nausea, palpitations and headache have been observed. Inhaled ipratropium does not decrease mucociliary clearance.[13] The inhalation itself can cause headache and irritation of the throat in a few percent of patients.[12]

Urinary retention has been reported in patients receiving doses by nebulizer. As a result, caution may be warranted, especially by men with prostatic hypertrophy.[15]

Interactions

Interactions with other anticholinergics like tricyclic antidepressants, anti-Parkinson drugs and quinidine, which theoretically increase side effects, are clinically irrelevant when ipratropium is administered as an inhalant.[12][13]

Pharmacology

Chemically, ipratropium bromide is a quaternary ammonium compound (which is indicated by the -ium per the BAN and the USAN) [16] obtained by treating atropine with isopropyl bromide, thus the name: isopropyl + atropine. It is chemically related to components of the plant Datura stramonium, which was used in ancient India for asthma.[17]

Ipratropium exhibits broncholytic action by reducing cholinergic influence on the bronchial musculature. It blocks muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, without specificity for subtypes, and therefore promotes the degradation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), resulting in a decreased intracellular concentration of cGMP.[18] Most likely due to actions of cGMP on intracellular calcium, this results in decreased contractility of smooth muscle in the lung, inhibiting bronchoconstriction and mucus secretion. It is a nonselective muscarinic antagonist,[12] and does not diffuse into the blood, which prevents systemic side effects. Ipratropium is a derivative of atropine[19] but is a quaternary amine and therefore does not cross the blood–brain barrier, which prevents central side effects (e.g., anticholinergic syndrome). Ipratropium should never be used in place of salbutamol (albuterol) as a rescue medication.

References

- "Ipratropium Bromide". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Al-Ahmad M, Hassab M, Al Ansari A (21 December 2020). "Allergic and Non-allergic Rhinitis". Textbook of Clinical Otolaryngology. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 241–252. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-54088-3_22. ISBN 978-3-030-54087-6. S2CID 234142758.

Nasal anticholinergics such as ipratropium bromide 0.03% are effective in controlling rhinorrhea, but do not relief other nasal symptoms. They block muscarinic receptors, leading to a decrease in the parasympathetic function.

- Briggs G, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ (2011). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation : a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 763. ISBN 978-1-60831-708-0.

- Ritter J, Flower RJ, Henderson G, Loke YK, MacEwan DJ, Rang HP (2020). Rang and Dale's pharmacology (9th ed.). Edinburgh. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-7020-8060-9. OCLC 1081403059.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 446. ISBN 978-3-527-60749-5.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Ipratropium - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Aaron SD (October 2001). "The use of ipratropium bromide for the management of acute asthma exacerbation in adults and children: a systematic review". The Journal of Asthma. 38 (7): 521–530. doi:10.1081/jas-100107116. PMID 11714074. S2CID 7335677.

- "Ipratropium Oral Inhalation". PubMed Health. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- "Ipratropium Bromide 0.5 mg/Albuterol Sulfate 3.0 mg" (PDF). FDA. 2004. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Atrovent Nasal Spray". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Haberfeld, H, ed. (2009). Austria-Codex (in German) (2009/2010 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. ISBN 978-3-85200-196-8.

- Dinnendahl, V; Fricke, U, eds. (2010). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). Vol. 2 (23 ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- "Ipratropium Soybean and Nuts Allergy". EMSMedRx. 21 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Afonso AS, Verhamme KM, Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MC, Brusselle GG (April 2011). "Inhaled anticholinergic drugs and risk of acute urinary retention". BJU International. 107 (8): 1265–1272. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09600.x. PMID 20880196. S2CID 29516074.

- "The Use of Common Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances". who.int. World Health Organization. 2000. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "History of Asthma". Allergy And Asthma. 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

... India, smoking the herb stramonium (an anticholinergic agent related to ipratropium and tiotropium currently used in inhalers) was used to relax the lungs.

- "Ipratropium". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012.

- Yamatake Y, Sasagawa S, Yanaura S, Okamiya Y (October 1977). "[Antiallergic asthma effect of ipatropium bromide (Sch 1000) in dogs (author's transl)]" [Antiallergic asthma effect of ipratropium bromide (Sch 1000) in dogs]. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. Folia Pharmacologica Japonica (in Japanese). 73 (7): 785–791. doi:10.1254/fpj.73.785. PMID 145994.