Clenbuterol

Clenbuterol is a sympathomimetic amine used by sufferers of breathing disorders as a decongestant and bronchodilator. People with chronic breathing disorders such as asthma use this as a bronchodilator to make breathing easier. It is most commonly available as the hydrochloride salt, clenbuterol hydrochloride.[2]

| |

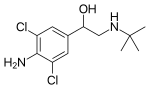

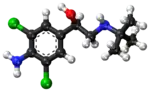

Clenbuterol (top), and (R)-(−)-clenbuterol (bottom) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dilaterol, Spiropent, Ventipulmin, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablets, oral solution) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 89–98% (orally) |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (negligible) |

| Elimination half-life | 36–48 hours |

| Excretion | Feces and urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.048.499 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H18Cl2N2O |

| Molar mass | 277.19 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

It was patented in 1967 and came into medical use in 1977.[3]

Medical uses

Clenbuterol is approved for use in some countries as a bronchodilator for asthma.

Clenbuterol is a β2 agonist with some structural and pharmacological similarities to epinephrine and salbutamol, but its effects are more potent and longer-lasting as a stimulant and thermogenic drug. It is commonly used for smooth muscle-relaxant properties as a bronchodilator and tocolytic.

It is classified by the World Anti-Doping Agency as an anabolic agent, not as a β2 agonist.[4]

Clenbuterol is prescribed for treatment of respiratory diseases for horses, and as an obstetrical aid in cattle.[5] It is illegal in some countries to use in livestock used for food.[6]

Side effects

Clenbuterol can cause these side effects:[7]

- Nervousness

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Tachycardia

- Subaortic stenosis

- High blood pressure

Overdosage

Use over the recommended dose of about 120 μg can cause muscle tremors, headache, dizziness, and gastric irritation. Persons self-administering the drug for weight loss or to improve athletic performance have experienced nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, palpitations, tachycardia, and myocardial infarction. Use of the drug may be confirmed by detecting its presence in semen or urine.[8]

Society and culture

Legal status

Clenbuterol is not an ingredient of any therapeutic drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and is now banned for IOC-tested athletes.[9] In the US, administration of clenbuterol to any animal that could be used as food for human consumption is banned by the FDA.[10][11]

Weight-loss

Although often used by bodybuilders during their "cutting" cycles,[12] the drug has been more recently known to the mainstream, particularly through publicized stories of use by celebrities such as Victoria Beckham,[9] Britney Spears, and Lindsay Lohan,[13] for its off-label use as a weight-loss drug similar to usage of other sympathomimetic amines such as ephedrine, despite the lack of sufficient clinical testing either supporting or negating such use. In 2021, Odalis Santos Mena, a Mexican fitness influencer, died after suffering a cardiac arrest while being anesthetized for a procedure of miraDry, a treatment that uses thermal energy to eliminate underarm sweat glands. The coroner reported that Mena's death was attributed to a combination of Clenbuterol and anesthesia.

Performance-enhancing drug

A common misconception about Clenbuterol is that it has anabolic properties, and can increase muscle mass when used in higher dosages. This claim has never been substantiated, and likely originated from equine research.[14] A beta-2 agonist, Clenbuterol has been found to increase short-term work rate and cardiovascular output, and consequently, its anabolic effects in horses can be attributed to exercise output and increased caloric intake. Given its ability to increase basal metabolic rate, maximum heart rate, and exercise output, Clenbuterol has ergogenic properties more closely related to ephedrine or amphetamine.

The notion that Clenbuterol is an anabolic agent likely originated from author and renowned authority on performance-enhancement Dan Duchaine. Duchaine popularized the drug in the bodybuilding community, and was the first to suggest the drug had muscle-building properties. Likewise, Duchaine erred in promoting the drug Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) as an anabolic agent, and served time for the unlawful possession and distribution of the drug in the mid-1990s.[15] As of 2011, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) listed Clenbuterol as an anabolic agent, despite the fact there is no evidence to suggest this is the case.[16]

Clenbuterol has also been used as a performance-enhancing drug. One issue is that clenbuterol is a food contaminant in some countries; doping control must distinguish between accidental and deliberate intake.[17][18]

Food contamination

Clenbuterol is occasionally referred to as "bute" and this risks confusion with phenylbutazone, also called "bute". Phenylbutazone, which is a drug also used with horses, was tested for in the 2013 European meat adulteration scandal.[19]

Intended to result in leaner meat with a higher muscle-to-fat ratio, the use of clenbuterol has been banned in meat since 1991 in the US and since 1996 in the European Union. The drug is banned due to health concerns about symptoms noted in consumers. These include increased heart rate, muscular tremors, headaches, nausea, fever, and chills. In several cases in Europe, these adverse symptoms have been temporary.[20]

Clenbuterol is a growth-promoting drug in the β agonist class of compounds. It is not licensed for use in China,[21] the United States,[20] or the EU[22] for food-producing animals, but some countries have approved it for animals not used for food, and a few countries have approved it for therapeutic uses in food-producing animals.

Not just athletes are affected by contamination. In Portugal, 50 people were reported as affected by clenbuterol in liver and pork between 1998 and 2002, while in 1990, veal liver was suspected of causing clenbuterol poisoning in 22 people in France and 135 people in Spain.[23]

In September 2006, some 330 people in Shanghai suffered from food poisoning after eating clenbuterol-contaminated pork.[24]

In February 2009, at least 70 people in one Chinese province (Guangdong) suffered food poisoning after eating pig organs believed to contain clenbuterol residue. The victims complained of stomach aches and diarrhea after eating pig organs bought in local markets.[25]

In March 2011, China's Ministry of Agriculture said the government would launch a one-year crackdown on illegal additives in pig feed, after a subsidiary of Shuanghui Group, China's largest meat producer, was exposed for using clenbuterol-contaminated pork in its meat products. A total of 72 people in central Henan Province, where Shuanghui is based, were taken into police custody for allegedly producing, selling, or using clenbuterol.[26] The situation has dramatically improved in China since September 2011, when a ban of clenbuterol was announced by China's Ministry of Agriculture.[27]

Authorities around the world appear to be issuing stricter food safety requirements, such as the Food Safety Modernization Act in the United States, Canada's revision of their import regulations, China's new food laws published since 2009, South Africa's new food law, and many more global changes and restrictions.

Veterinary use

Clenbuterol is administered as an aerosol for the treatment of allergic respiratory disease in horses as a bronchodilator, and intravenously in cattle to relax the uterus in cows at the time of parturition,[28] specifically to facilitate exteriorisation of the uterus during Caesarian section surgery. It is licensed for obstetrical use in cattle as Planipart Solution for Injection.[29]

See also

- Mabuterol (same structure as clenbuterol but one of the chloro groups has been changed to a trifluoromethyl group instead).

- Cimaterol

References

- Center for Veterinary Medicine. "FOIA Drug Summaries - NADA 140-973 VENTIPULMIN® SYRUP - original approval". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- "874. Clenbuterol (WHO Food Additives Series 38)". www.inchem.org. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 543. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Pluim BM, de Hon O, Staal JB, Limpens J, Kuipers H, Overbeek SE, et al. (January 2011). "β₂-Agonists and physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Sports Medicine. 41 (1): 39–57. doi:10.2165/11537540-000000000-00000. PMID 21142283. S2CID 189906919.

- "Presentation". www.noahcompendium.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Dowling PM. "Systemic Therapy of Inflammatory Airway Disease". Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "Clenbuterol - SteroidAbuse .com". www.steroidabuse.com. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 325–326.

- Guest K (2007-04-10). "Clenbuterol: The new weight-loss wonder drug gripping Planet Zero". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2007-04-08. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- FDA's Prohibited Drug List, Food Animal Residue Avoidance & Depletion Program

- "Animal Drugs @ FDA". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- "Anabolic Steroids and SARMS Handbook for Bodybuilders and Athletes". Retrieved 2019-06-16.

- "Clenbuterol Weight Loss Hollywood Secret". PRBuzz. London. 2012-05-17. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- Kearns CF. "Clenbuterol and the Horse Revisisted". Research Gate. The Veterinary Journal. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Assael S. "Dan Duchaine: a founding father of the steroid movement". espn.com. ESPN. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Pluim BM, de Hon O, Staal JB, Limpens J, Kuipers H, Overbeek SE, et al. (January 2011). "β₂-Agonists and physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Sports Medicine. 41 (1): 39–57. doi:10.2165/11537540-000000000-00000. PMID 21142283. S2CID 189906919.

- Guddat S, Fußhöller G, Geyer H, Thomas A, Braun H, Haenelt N, et al. (June 2012). "Clenbuterol - regional food contamination a possible source for inadvertent doping in sports". Drug Testing and Analysis. 4 (6): 534–538. doi:10.1002/dta.1330. PMID 22447758.

- Velasco-Bejarano B, Velasco-Carrillo R, Camacho-Frias E, Bautista J, López-Arellano R, Rodríguez L (June 2022). "Detection of clenbuterol residues in beef sausages and its enantiomeric analysis using UHPLC-MS/MS: A risk of unintentional doping in sport field". Drug Testing and Analysis. 14 (6): 1130–1139. doi:10.1002/dta.3235. PMC 9303807. PMID 35132808.

- "Horse meat investigation. Advice for consumers". Enforcement and regulation. Food Standards Agency. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- "Clenbuterol". Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). July 1995. Archived from the original on 2012-08-29. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- "China bans production, sale of clenbuterol to improve food safety". Archived from the original on 2011-10-03. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Animal Nutrition - Undesirable Substances". European Commission. Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Anti Doping Advisory Notes". Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Research Brief: Food Safety in China (PDF). China Environmental Health Project, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. June 28, 2007.

- "China: 70 ill from tainted pig organs". CNN. 2009-02-23. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- "China to launch one-year crackdown on contaminated pig feed – xinhuanet.com". Xinhua. 2011-03-28. Archived from the original on April 1, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- Bottemiller H (April 26, 2011). "Amid Scandal, China Bans More Food Additives". Food Safety News. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- Planipart Solution for Injection 30 micrograms/ml: Uses Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, National Office of Animal Health

- "Presentation". www.noahcompendium.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-01-24.