Malik-Shah I

Malik-Shah I (Persian: ملک شاه), was the third sultan of the Seljuk Empire from 1072 to 1092, under whom the sultanate reached its zenith of power and influence.[3]

| Malik-Shah I | |

|---|---|

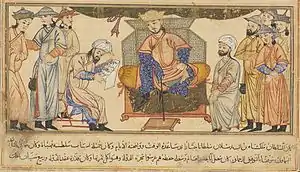

Investiture scene of Malik-Shah I, from the 14th-century book Jami' al-tawarikh | |

| Sultan of the Great Seljuk Empire | |

| Reign | 15 December 1072 – 19 November 1092 |

| Predecessor | Alp Arslan |

| Successor | Mahmud I |

| Born | 16 August 1055 Isfahan, Seljuk Empire |

| Died | 19 November 1092 (aged 37) Baghdad, Seljuk Empire |

| Burial | Isfahan |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue |

|

| House | Seljuk |

| Father | Alp Arslan |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

During his youth, he spent his time participating in the campaigns of his father Alp Arslan, along with the latter's vizier Nizam al-Mulk. During one of such campaigns in 1072, Alp Arslan was fatally wounded and died only a few days later. After that, Malik-Shah was crowned as the new sultan of the empire, but the succession was contested by his uncle Qavurt. Although Malik-Shah was the nominal head of the Seljuk state, Nizam al-Mulk held near absolute power during his reign.[4] Malik-Shah spent the rest of his reign waging war against the Karakhanids on the eastern side, and establishing order in the Caucasus.

Malik-Shah's death to this day remains under dispute; according to some scholars, he was poisoned by Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadi, while others say that he was poisoned by the supporters of Nizam al-Mulk.

Etymology

Although he was known by several names, he was mostly known as "Malik-Shah", a combination of the Arabic word malik (king) and the Persian word shah (which also means king).

Early life

Malik-Shah was born on 16 August 1055 and spent his youth in Isfahan. According to the 12th-century Persian historian Muhammad bin Ali Rawandi, Malik-Shah had fair skin, was tall and somewhat bulky.[5] In 1064, Malik-Shah, only 9 years old by then, along with Nizam al-Mulk, the Persian vizier of the Empire,[6] took part in Alp Arslan's campaign in the Caucasus. The same year, Malik-Shah was married to Terken Khatun, the daughter of the Karakhanid khan Ibrahim Tamghach-Khan.[5] In 1066, Alp Arslan arranged a ceremony near Merv, where he appointed Malik-Shah as his heir and also granted him Isfahan as a fief.[7][5]

In 1071, Malik-Shah took part in the Syrian campaign of his father, and stayed in Aleppo when his father fought the Byzantine emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at Manzikert.[5] In 1072, Malik-Shah and Nizam al-Mulk accompanied Alp-Arslan during his campaign in Transoxiana against the Karakhanids. However, Alp-Arslan was badly wounded during his expedition, and Malik-Shah shortly took over the army. Alp-Arslan died some days later, and Malik-Shah was declared as the new sultan of the empire.

Reign

War of succession

However, right after Malik-Shah's accession, his uncle Qavurt claimed the throne for himself and sent Malik-Shah a message which said: "I am the eldest brother, and you are a youthful son; I have the greater right to my brother Alp-Arslan's inheritance." Malik-Shah then replied by sending the following message: "A brother does not inherit when there is a son."[8] This message enraged Qavurt, who thereafter occupied Isfahan. In 1073 a battle took place near Hamadan, which lasted three days. Qavurt was accompanied by his seven sons, and his army consisted of Turkmens, while the army of Malik-Shah consisted of ghulams ("military slaves") and contingents of Kurdish and Arab troops.[8]

During the battle, the Turks of Malik-Shah's army mutinied against him, but he nevertheless managed to defeat and capture Qavurt.[5][9] Qavurt then begged for mercy and in return promised to retire to Oman. However, Nizam al-Mulk declined the offer, claiming that sparing him was an indication of weakness. After some time, Qavurt was strangled to death with a bowstring, while two of his sons were blinded. After having dealt with that problem, Malik-Shah appointed Qutlugh-Tegin as the governor of Fars and Sav-Tegin as the governor of Kerman.[10]

Warfare with Karakhanids

Malik-Shah then turned his attention towards the Karakhanids, who had after the death of Alp-Arslan invaded Tukharistan, which was ruled by Malik-Shah's brother Ayaz, who was unable to repel the Karakhanids and was killed by them. Malik-Shah eventually managed to repel the Karakhanids and captured Tirmidh, giving Sav-Tegin the key of the city. Malik-Shah then appointed his other brother Shihab al-Din Tekish as the ruler of Tukharistan and Balkh.[11] During the same period, the Ghaznavid ruler Ibrahim was seizing Seljuk territory in northern Khorasan, but was defeated by Malik-Shah, who then made peace with the latter and gave his daughter Gawhar Khatun in marriage to Ibrahim's son Mas'ud III.[12][5][13]

Other wars

In 1074, Malik-Shah ordered the Turkic warlord Arghar to restore what he had destroyed during his raids in the territory of the Shirvanshah Fariburz I.[14] During the same year, he appointed Qavurt's son Rukn al-Dawla Sultan-Shah as the ruler of Kerman.[10] One year later, Malik-Shah sent an army under Sav-Tegin to Arran, which was ruled by the Shaddadid ruler Fadlun III. Sav-Tegin managed to easily conquer the region, thus ending Shaddadid rule. Malik-Shah then gave Gorgan to Fadlun III as a fief.[15] Throughout Malik's reign new institutions of learning were established[16] and it was during this time that the Jalali calendar was reformed at the Isfahan observatory.[17] In 1086–87, he led an expedition to capture Edessa, Manbij, Aleppo, Antioch and Latakia.[18] During this expedition, he appointed Aq Sunqur governor of Aleppo and received homage of the Arab emir of Shaizar, Nasir ibn Ali ibn Munquidh.[19] In 1089, Malik-Shah captured Samarkand with the support of the local clergy, and imprisoned its Karakhanid ruler Ahmad Khan ibn Khizr, who was the nephew of Terken Khatun. He then marched to Semirechye, and made the Karakhanid Harun Khan ibn Sulayman, the ruler of Kashgar and Khotan, acknowledge him as his suzerain.[5]

Domestic policy and Ismailis

In 1092, Nizam al-Mulk was assassinated near Sihna, on the road to Baghdad, by a man disguised as a Sufi.[20] As the assassin was immediately cut down by Nizam's bodyguard, it became impossible to establish with certainty who had sent him. One theory had it that he was an Assassin, since these regularly made attempts on the lives of Seljuk officials and rulers during the 11th century. Another theory had it that the attack had been instigated by Malik-Shah, who may have grown tired of his overmighty vizier.[21] After Nizam al-Mulk's death, Malik-Shah appointed another Persian named Taj al-Mulk Abu'l Ghana'im as his vizier.[5] Malik-Shah then went to Baghdad and decided to depose al-Muqtadi and sent him the following message: "You must relinquish Baghdad to me, and depart to any land you choose." This was because Malik-Shah wanted to appoint his grandson (or nephew) Ja'far as the new caliph.[5][22]

The Sultan had a good relationship with the Shias at large except for the Ismailis of Hassan ibn Sabbah. Followers of Sabbah managed to occupy the Alamut fortress near Qazvin, and the army under the command of the emir Arslan-Tash, sent by Malik Shah, could not recapture it. The Sultan's ghilman, Kizil Sarug, besieged the Daru fortress in Kuhistan, but ceased hostilities in connection with the death of Malik Shah on November 19, 1092, possibly due to poisoning.[23]

Death and aftermath

Malik-Shah died on 19 November 1092 while he was hunting. He was most likely poisoned by the caliph or the supporters of Nizam al-Mulk. Under the orders of Terken Khatun, Malik-Shah's body was taken back to Isfahan, where it was buried in a madrasa.[5][24]

Upon his death, the Seljuk Empire fell into chaos, as rival successors and regional governors carved up their empire and waged war against each other. The situation within the Seljuk lands was further complicated by the beginning of the First Crusade, which detached large portions of Syria and Palestine from Muslim control in 1098 and 1099. The success of the First Crusade is at least in part attributable to the political confusion which resulted from Malik-Shah's death.[25]

Family

One of his wives was Terken Khatun. She was the daughter of Tamghach Khan Ibrahim.[26] She was born in 1053. They married in 1065.[27] She had five sons, Dawud, who died in 1082, Ahmed, who died in 1088–9, aged eleven, Sultan Mahmud I, born in 1087–8,[28] Abu'l-Qasim, who died in childhood, and another son who died in childhood, and was buried in Ray.[29] She died in 1094.[30] Another of his wives was Zubayda Khatun. She was born in 1056.[31] She was the daughter of Yaquti, and the granddaughter of Chaghri Beg. She was the mother of Malik-Shah's eldest son, Sultan Barkiyaruq.[32] She died in 1099.[31] One of his concubines[29] was Taj al-Din Khatun Safariyya,[33] also known as Bushali.[29] She was the mother of Sultans Muhammad Tapar and Ahmad Sanjar,[33] and another son who died in childhood, and was buried in Ray.[29] She died in Merv in 1121.[34]

Two other sons, whose mothers are unknown were Tughril and Amir Khumarin, who was born with white hairs over his body and white eyelashes.[29] One of his daughters, Mah-i Mulk Khatun, whose mother was Terken Khatun,[35] married Abbasid Caliph Al-Muqtadi in 1082.[36] Another daughter, Sitara Khatun, was married to Garshasp II, son of Ali ibn Faramurz.[37] Another daughter married Najm al-Daula, son of Shahriyar ibn Qarin.[38] Another daughter was married by Sanjar to the Ispahbud Taj al-Multk Mardavij, son of Ali ibn Mardavij.[38] Another daughter, Terken Khatun,[39] was married to the Kara-Khanid Muhammad Arslan Khan. Their son Rukn al-Din Mahmud Khan, succeeded Sanjar in Khurasan.[27] Another daughter, Gawhar Khatun, was married to Mas'ud III of Ghazni.[27] Another daughter, Ismah Khatun,[36] married Abbasid Caliph Al-Mustazhir in 1109.[40]

Legacy

The 18th century English historian Edward Gibbon wrote of him:

On his father's death the inheritance was disputed by an uncle, a cousin, and a brother: they drew their cimeters, and assembled their followers; and the triple victory of Malek Shah established his own reputation and the right of primogeniture. In every age, and more especially in Asia, the thirst of power has inspired the same passions, and occasioned the same disorders; but, from the long series of civil war, it would not be easy to extract a sentiment more pure and magnanimous than is contained in the saying of the Turkish prince. On the eve of the battle, he performed his devotions at Thous, before the tomb of the Imam Riza. As the sultan rose from the ground, he asked his vizier Nizam, who had knelt beside him, what had been the object of his secret petition: "That your arms may be crowned with victory," was the prudent, and most probably the sincere, answer of the minister. "For my part," replied the generous Malek, "I implored the Lord of Hosts that he would take from me my life and crown, if my brother be more worthy than myself to reign over the Moslems." The favourable judgment of heaven was ratified by the caliph; and for the first time, the sacred title of Commander of the Faithful was communicated to a Barbarian. But this Barbarian, by his personal merit, and the extent of his empire, was the greatest prince of his age.[41]

Personality

Malik-Shah displayed substantial interest in science, art and literature.[42] The Isfahan Observatory or Malikshah Observatory was constructed during his reign, closing shortly after his death in 1092.[43] It was from the work at the observatory that the Jalali Calendar was adopted.[44] He thought highly of the art of architecture as well, as he enjoyed building new and splendid mosques in his capital, Isfahan. He was religiously tolerant which is supported by the fact that during his reign, subjects of the Seljuk Empire enjoyed internal peace and religious tolerance. Malik-Shah also showed lenience towards exquisite poetry as his reign is also memorable for the poetry of Omar Khayyam.[42]

Despite being arguably the most powerful monarch of his era, it is believed that Malik-Shah was unpretentious and modest. The legend has it that during the years that were hugely successful for Seljuks on all fronts, Malik-Shah, overwhelmed by the imperial might of his dynasty, used to climb to the top of a hill and say the following: "Oh Almighty God, I will somehow cope with the problem of hunger, please save me from the threat of abundance".[45]

Malik Shah did not spend as much time on campaign as his prominent predecessor Tughril or his father Alp Arslan did. Isfahan became securely established as his chief city of residence, although in the latter years of his rule Malik Shah preferred to winter in Baghdad. Whereas Alp Arslan had spent just over a year out of his decade-long reign in Isfahan, Malik Shah resided there for more than half of his rule. Isfahan also served as the burial site of Malik Shah, his descendants, as well as celebrated bureaucrats of the sultanate like Nizam al-Mulk. Malik Shah's decision of residing in a capital far away from the centers of Turkmen settlement around Merv, Rayy, Hamadan, and Azerbaijan could well be explained by the increasing distance between him and his nomadic subjects.[46]

References

- Henry Melvill Gwatkin (1923). The Cambridge Medieval History: The Eastern Roman empire (717-1453). p. 307.

Malik Shāh was recognised by the Caliph as his successor, and invested with the title of 'Amir-al-Mu'minin

- Massignon 1982, p. 162.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2019). Middle East Conflicts from Ancient Egypt to the 21st Century: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Volume 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 790. ISBN 978-1-440-85353-1.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960–1985). The Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. 8. Leiden: Brill. p. 70.

- Durand-Guédy 2012.

- Luther 1985, pp. 895–898.

- Bosworth 1968, p. 61.

- Bosworth 1968, p. 88.

- Bosworth 1968, pp. 88–89.

- Bosworth 1968, p. 89.

- Bosworth 1968, pp. 90–91.

- Bosworth 2002, p. 179.

- Bosworth 1968, p. 94.

- Minorsky 1958, p. 40.

- Bosworth 1968, p. 95.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960–1985). The Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. 8. Leiden: Brill. p. 71.

- Djalali, S. H. Taqizadeh, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. 2, Ed. B. Lewis, C. Pellat and J. Schacht, (E. J. Brill, 1991), 397-398.

- Purton 2009, p. 184.

- Richards 2002, p. 226.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960–1985). The Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. 8. Leiden: Brill. pp. 69–72.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960–1985). The Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. 8. Leiden: Brill. p. 72.

- Bosworth 1968, p. 101.

- Stroeva L.V. "The State of the Ismailis in Iran in the XI - XIII centuries". - Publishing House: "Science", 1978. p. 67, 69, 71

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960–1985). The Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. 7. Leiden: Brill. p. 275.

- Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Oxford History of the Crusades, (Oxford University Press, 2002), 213.

- Lambton 1988, p. 11.

- Lambton 1988, p. 263.

- Lambton 1988, pp. 226–7.

- Bosworth, E. (2013). The History of the Seljuq Turks: The Saljuq-nama of Zahir al-Din Nishpuri. Taylor & Francis. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-136-75258-2.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Boyle, John Andrew; Gershevitch, Ilya; Yarshater, Ehsan; Frye, Richard Nelson (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge histories online. Cambridge University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-521-06936-6.

- Browne, E.G. (2013). A Literary History of Persia: 4 Volume Set. Library of literary history. Taylor & Francis. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-134-56835-2.

- Lambton 1988, pp. 227.

- Lambton 1988, p. 35.

- Richards 2002, p. 232.

- El-Hibri, T. (2021). The Abbasid Caliphate: A History. Cambridge University Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-107-18324-7.

- al-Sāʿī, Ibn; Toorawa, Shawkat M.; Bray, Julia (2017). كتاب جهات الأئمة الخلفاء من الحرائر والإماء المسمى نساء الخلفاء: Women and the Court of Baghdad. Library of Arabic Literature. NYU Press. pp. 62, 63. ISBN 978-1-4798-6679-3.

- Lambton 1988, p. 261.

- Lambton 1988, p. 262.

- Basan, O.A. (2010). The Great Seljuqs: A History. Routledge Studies in the History of Iran and Turkey. Taylor & Francis. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-136-95393-4.

- Lambton 1988, p. 268.

- Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, New York: The Modern Library, n.d. v. 3, p. 406.

- "Malik-Shāh". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Sayili, Aydin (1960). The Observatory in Islam and Its Place in the General History of the Observatory. Publications of the Turkish Historical Society, Series VII, No. 38. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi. pp. 159–66. Bibcode:1960oipg.book.....S.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam. Kalın, İbrahim. Oxford. 2014. p. 92. ISBN 9780199812578. OCLC 868981941.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - "in Russian".

- Peacock, A.C.S. (2015). The Great Seljuk Empire. Edinburgh University Press Ltd. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7486-3827-7.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E. (1968). "The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000–1217)". In Frye, R. N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 5: The Saljuq and Mongol periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–202. ISBN 0-521-06936-X.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (2002). "GOWHAR ḴĀTUN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI, Fasc. 2. London et al. p. 179.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bosworth, C. E (1995). The Later Ghaznavids: Splendour and Decay: The Dynasty in Afghanistan and Northern India 1040-1186. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Private, Limited. ISBN 9788121505772. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Durand-Guédy, David (2012). "MALEKŠĀH". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Lambton, A.K.S. (1988). Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia. Bibliotheca Persica. Bibliotheca Persica. ISBN 978-0-88706-133-2.

- Luther, K. A. (1985). "ALP ARSLĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 8-9. pp. 895–898.

- Massignon, Louis (1982). The Passion of al-Hallaj, Mystic and Martyr of Islam. Vol. 2. Translated by Mason, Herbert. Princeton University Press.

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1958). A History of Sharvān and Darband in the 10th-11th Centuries. University of Michigan. pp. 1–219. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Richards, Donald Sydney (2002). The Annals of the Saljuq Turks: Selections from Al-Kāmil Fīʻl-Taʻrīkh of ʻIzz Al-Dīn Ibn Al-Athīr. Psychology Press. ISBN 0700715762.

- Peacock, Andrew. "SHADDADIDS". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Purton, Peter Fraser (2009). A History of the Early Medieval Siege, C. 450-1220. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 9781843834489.