Gilbert's syndrome

Gilbert syndrome (GS) is a syndrome in which the liver of affected individuals processes bilirubin more slowly than the majority.[1] Many people never have symptoms.[1] Occasionally jaundice (a slight yellowish color of the skin or whites of the eyes) may occur.[1]

| Gilbert's syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gilbert syndrome, Meulengracht syndrome, Gilbert-Lereboullet syndrome, hyperbilirubinemia Arias type, hyperbilirubinemia type 1, familial cholemia, familial nonhemolytic jaundice[1][2] |

| |

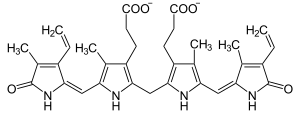

| Bilirubin | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Usually none. Abdominal pain, nausea, tired and weak feeling, slight jaundice[1] |

| Complications | Usually none[1] |

| Causes | Genetic[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Crigler–Najjar syndrome, Rotor syndrome, Dubin–Johnson syndrome[2] |

| Treatment | None typically needed[1] |

| Frequency | ~5%[3] |

Gilbert syndrome is due to a genetic variant in the UGT1A1 gene which results in decreased activity of the bilirubin uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase enzyme.[1][3] It is typically inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern and occasionally in an autosomal dominant pattern depending on the type of variant.[3] Episodes of jaundice may be triggered by stress such as exercise, menstruation, or not eating.[3] Diagnosis is based on higher levels of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood without either signs of other liver problems or red blood cell breakdown.[2][3]

Typically no treatment is needed.[1] Gilbert syndrome is associated with decreased cardiovascular health risks.[4] If jaundice is significant phenobarbital may be used, which aids in the conjugation of bilirubin.[1] Gilbert syndrome affects about 5% of people in the United States.[3] Males are more often diagnosed than females.[1] It is often not noticed until late childhood to early adulthood.[2] The condition was first described in 1901 by Augustin Nicolas Gilbert.[5][2][6]

Signs and symptoms

Jaundice

Gilbert syndrome produces an elevated level of unconjugated bilirubin in the bloodstream, but normally has no consequences. Mild jaundice may appear under conditions of exertion, stress, fasting, and infections, but the condition is otherwise usually asymptomatic.[7][8] Severe cases are seen by yellowing of the skin tone and yellowing of the conjunctiva in the eye.[9]

Gilbert syndrome has been reported to contribute to an accelerated onset of neonatal jaundice. The syndrome cannot cause severe indirect hyperbilirubinemia in neonates by itself, but it may have a summative effect on rising bilirubin when combined with other factors,[10] for example in the presence of increased red blood cell destruction due to diseases such as G6PD deficiency.[11][12] This situation can be especially dangerous if not quickly treated, as the high bilirubin causes irreversible neurological disability in the form of kernicterus.[13][14][15]

Detoxification of certain drugs

The enzymes that are defective in GS – UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, polypeptide A1 (UGT1A1) – are also responsible for some of the liver's ability to detoxify certain drugs. For example, Gilbert syndrome is associated with severe diarrhea and neutropenia in patients who are treated with irinotecan, which is metabolized by UGT1A1.[16]

While paracetamol (acetaminophen) is not metabolized by UGT1A1,[17] it is metabolized by one of the other enzymes also deficient in some people with GS.[18][19] A subset of people with GS may have an increased risk of paracetamol toxicity.[19][20]

Cardiovascular effects

The mild increase in unconjugated bilirubin due to Gilbert syndrome is closely related to the reduction in the prevalence of chronic diseases, especially cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, related risk factors, and all-cause mortality.[21] Observational studies emphasize that the antioxidant effects of unconjugated bilirubin may bring survival benefits to patients.[22]

Several analyses have found a significantly decreased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) in individuals with GS.[23][24]

Specifically, people with mildly elevated levels of bilirubin (1.1 mg/dl to 2.7 mg/dl) were at lower risk for CAD and at lower risk for future heart disease.[25] These researchers went on to perform a meta-analysis of data available up to 2002, and confirmed the incidence of atherosclerotic disease (hardening of the arteries) in subjects with GS had a close and inverse relationship to the serum bilirubin.[23] This beneficial effect was attributed to bilirubin IXα which is recognized as a potent antioxidant, rather than confounding factors such as high-density lipoprotein levels.[25]

This association was also seen in long-term data from the Framingham Heart Study.[26][4] Moderately elevated levels of bilirubin in people with GS and the (TA)7/(TA)7 genotype were associated with one-third the risk for both coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease as compared to those with the (TA)6/(TA)6 genotype (i.e. a normal, nonmutated gene locus).

Platelet counts and MPV (mean platelet volume) are decreased in patients with Gilbert's syndrome. The elevated levels of bilirubin and decreasing levels of MPV and CRP in Gilbert's syndrome patients may have an effect on the slowing down of the atherosclerotic process.[27]

Other

Symptoms, whether connected or not to GS, have been reported in a subset of those affected: fatigue (feeling tired all the time), difficulty maintaining concentration, unusual patterns of anxiety, loss of appetite, nausea, abdominal pain, loss of weight, itching (with no rash), and others,[28] such as humor change or depression. But scientific studies found no clear pattern of adverse symptoms related to the elevated levels of unconjugated bilirubin in adults. However, other substances glucuronidized by the affected enzymes in those with Gilbert's syndrome could theoretically, at their toxic levels, cause these symptoms.[29][30] Consequently, debate exists about whether GS should be classified as a disease.[29][31] However, Gilbert syndrome has been linked to an increased risk of gallstones.[28][32]

Cause

Mutations in the UGT1A1 gene lead to Gilbert Syndrome.[33] The gene provides instructions for making the bilirubin uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (bilirubin-UGT) enzyme, which can be found in the liver cells and responsible for the removal of bilirubin from the body.[34]

The bilirubin-UGT enzyme performs a chemical reaction called glucuronidation. Glucuronic acid is transferred to unconjugated bilirubin, which is a yellowish pigment made when your body breaks down old red blood cells,[35] and then being converted to conjugated bilirubin during the reaction. Conjugated bilirubin passes from the liver into the intestines with bile. It's then excreted in stool.

People with Gilbert syndrome have approximately 30 percent of normal bilirubin-UGT enzyme function, which contributes to a lower rate of glucuronidation of unconjugated bilirubin. This substance then accumulates in the body, causing mild hyperbilirubinemia.[34]

Genetics

Gilbert syndrome is a phenotypic effect, mostly associated with increased blood bilirubin levels, but also sometimes characterized by mild jaundice due to increased unconjugated bilirubin, that arises from several different genotypic variants of the gene for the enzyme responsible for changing bilirubin to the conjugated form.

Gilbert's syndrome is characterized by a 70–80% reduction in the glucuronidation activity of the enzyme (UGT1A1). The UGT1A1 gene is located on human chromosome 2.[36]

More than 100 polymorphisms of the UGT1A1 gene are known, designated as UGT1A1*n (where n is the general chronological order of discovery), either of the gene itself or of its promoter region. UGT1A1 is associated with a TATA box promoter region; this region most commonly contains the genetic sequence A(TA)6TAA; this variant accounts for about 50% of alleles in many populations. However, several allelic polymorphic variants of this region occur, the most common of which results from adding another dinucleotide repeat TA to the promoter region, resulting in A(TA)7TAA, which is called UGT1A1*28; this common variant accounts for about 40% of alleles in some populations, but is seen less often, around 3% of alleles, in Southeast and East Asian people and Pacific Islanders.

In most populations, Gilbert syndrome is most commonly associated with homozygous A(TA)7TAA alleles.[37][38][39] In 94% of GS cases, two other glucuronosyltransferase enzymes, UGT1A6 (rendered 50% inactive) and UGT1A7 (rendered 83% ineffective), are also affected.

However, Gilbert syndrome can arise without TATA box promoter polymorphic variants; in some populations, particularly healthy Southeast and East Asians, Gilbert's syndrome is more often a consequence of heterozygote missense mutations (such as Gly71Arg also known as UGT1A1*6, Tyr486Asp also known as UGT1A1*7, Pro364Leu also known as UGT1A1*73) in the actual gene coding region,[20] which may be associated with significantly higher bilirubin levels.[20]

Because of its effects on drug and bilirubin breakdown and because of its genetic inheritance, Gilbert's syndrome can be classed as a minor inborn error of metabolism.

Diagnosis

People with GS predominantly have elevated unconjugated bilirubin, while conjugated bilirubin is usually within the normal range or is less than 20% of the total. Levels of bilirubin in GS patients are reported to be from 20 μM to 90 μM (1.2 to 5.3 mg/dl)[38] compared to the normal amount of < 20 μM. GS patients have a ratio of unconjugated/conjugated (indirect/direct) bilirubin commensurately higher than those without GS.

The level of total bilirubin is often further increased if the blood sample is taken after fasting for two days,[40] and a fast can, therefore, be useful diagnostically. A further conceptual step that is rarely necessary or appropriate is to give a low dose of phenobarbital:[41] the bilirubin will decrease substantially.

Tests can also detect DNA variants of UGT1A1 by polymerase chain reaction or DNA fragment sequencing.

Differential diagnosis

While Gilbert syndrome is considered harmless, it is clinically important because it may give rise to a concern about a blood or liver condition, which could be more dangerous. However, these conditions have additional indicators:

- In GS, unless another disease of the liver is also present, the liver enzymes ALT/SGPT and AST/SGOT, as well as albumin, are within normal ranges.

- More severe types of glucuronyl transferase disorders such as Crigler–Najjar syndrome (types I and II) are much more severe, with 0–10% UGT1A1 activity, with affected individuals at risk of brain damage in infancy (type I) and teenage years (type II).

- Hemolysis of any cause can be excluded by a full blood count, haptoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase levels, and the absence of reticulocytosis (elevated reticulocytes in the blood would usually be observed in haemolytic anaemia).

- Dubin–Johnson syndrome and Rotor syndrome are rarer autosomal recessive disorders characterized by an increase of conjugated bilirubin.

- Viral hepatitis associated with increase of conjugated bilirubin can be excluded by negative blood samples for antigens specific to the different hepatitis viruses.

- Cholestasis can be excluded by normal levels of bile acids in plasma, the absence of lactate dehydrogenase, low levels of conjugated bilirubin, and ultrasound scan of the bile ducts.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency - elevated bilirubin levels (and MCV counts above 90–92) can be associated with a vitamin B12 deficiency.

Treatment

Typically no treatment is needed.[1] If jaundice is significant phenobarbital may be used.[1]

History

Gilbert syndrome was first described by French gastroenterologist Augustin Nicolas Gilbert and co-workers in 1901.[6][5] In German literature, it is commonly associated with Jens Einar Meulengracht.[42]

Alternative, less common names for this disorder include:

- Familial benign unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia

- Constitutional liver dysfunction

- Familial non-hemolytic non-obstructive jaundice

- Icterus intermittens juvenilis

- Low-grade chronic hyperbilirubinemia

- Unconjugated benign bilirubinemia

Society and culture

Notable cases

- Napoleon[43]

- Arthur Kornberg, Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine, 1959[44]

- Nicky Wire, Manic Street Preachers bassist[45]

- Alexandr Dolgopolov (tennis player)[46]

- Jonas Folger, MotoGP rider[47]

- Huo Yuanjia (master of Chinese martial art)

- David Barnea (Mossad Chief)

References

- "Gilbert syndrome". GARD. 2016. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- "Gilbert Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2015. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- "Gilbert syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. 27 June 2017. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Bulmer, A. C.; Verkade, H. J.; Wagner, K.-H. (April 2013). "Bilirubin and beyond: a review of lipid status in Gilbert's syndrome and its relevance to cardiovascular disease protection". Progress in Lipid Research. 52 (2): 193–205. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2012.11.001. hdl:10072/54228. ISSN 1873-2194. PMID 23201182.

- Gilbert A, Lereboullet P (1901). "La cholémie simple familiale". La Semaine Médicale. 21: 241–3.

- "Whonamedit – dictionary of medical eponyms". www.whonamedit.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Kasper et al., Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th edition, McGraw-Hill 2005

- Boon et al., Davidson's Principles & Practice of Medicine, 20th edition, Churchill Livingstone 2006

- Philadelphia, The Children's Hospital of (2014-08-23). "Hyperbilirubinemia and Jaundice". www.chop.edu. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- Saki, F.; Hemmati, F.; Haghighat, M. (2011). "Prevalence of Gilbert syndrome in parents of neonates with pathologic indirect hyperbilirubinemia". Annals of Saudi Medicine. 31 (2): 140–4. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.77498. PMC 3102472. PMID 21403409.

- Bancroft JD, Kreamer B, Gourley GR (1998). "Gilbert syndrome accelerates development of neonatal jaundice". Journal of Pediatrics. 132 (4): 656–60. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70356-7. PMID 9580766.

- Cappellini MD, Di Montemuros FM, Sampietro M, Tavazzi D, Fiorelli G (1999). "The interaction between Gilbert's syndrome and G6PD deficiency influences bilirubin levels". British Journal of Haematology. 104 (4): 928–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.1999.1331a.x. PMID 10192462. S2CID 40300539.

- Usman, Fatima; Diala, Udochukwu; Shapiro, Steven; Le Pichon, Jean-Baptiste; Slusher, Tina (2018). "Acute bilirubin encephalopathy and its progression to kernicterus: current perspectives". Research and Reports in Neonatology. 8: 33–44. doi:10.2147/RRN.S125758.

- Rennie, Janet M.; Beer, Jeanette; Upton, Michele (2019). "Learning from claims: hyperbilirubinaemia and kernicterus". Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 104 (2): F202–F204. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2017-314622. PMC 6580733. PMID 29802103.

- Reddy, D. K.; Pandey, S. (2021). Kernicterus. StatPearls. PMID 32644546.

- Marcuello E, Altés A, Menoyo A, Del Rio E, Gómez-Pardo M, Baiget M (2004). "UGT1A1 gene variations and irinotecan treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer". Br J Cancer. 91 (4): 678–82. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602042. PMC 2364770. PMID 15280927.

- Rauchschwalbe S, Zuhlsdorf M, Wensing G, Kuhlmann J (2004). "Glucuronidation of acetaminophen is independent of UGT1A1 promotor genotype". Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 42 (2): 73–7. doi:10.5414/cpp42073. PMID 15180166.

- Kohle C, Mohrle B, Munzel PA, Schwab M, Wernet D, Badary OA, Bock KW (2003). "Frequent co-occurrence of the TATA box mutation associated with Gilbert's syndrome (UGT1A1*28) with other polymorphisms of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase-1 locus (UGT1A6*2 and UGT1A7*3) in Caucasians and Egyptians". Biochem Pharmacol. 65 (9): 1521–7. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00074-1. PMID 12732365.

- Esteban A, Pérez-Mateo M (1999). "Heterogeneity of paracetamol metabolism in Gilbert's syndrome". European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 24 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1007/BF03190005. PMID 10412886. S2CID 27543027.

- Gilbert Syndrome at eMedicine

- Wagner, K. H.; Shiels, R. G.; Lang, C. A.; Seyed Khoei, N.; Bulmer, A. C. (2018). "Diagnostic criteria and contributors to Gilbert's syndrome". Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 55 (2): 129–139. doi:10.1080/10408363.2018.1428526. PMID 29390925. S2CID 46870015.

- King, D.; Armstrong, M. J. (2019). "Overview of Gilbert's syndrome". Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. 57 (2): 27–31. doi:10.1136/dtb.2018.000028. PMID 30709860. S2CID 73447592.

- Ladislav Novotnýc; Libor Vítek (2003). "Inverse Relationship Between Serum Bilirubin and Atherosclerosis in Men: A Meta-Analysis of Published Studies". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 228 (5): 568–571. doi:10.1177/15353702-0322805-29. PMID 12709588. S2CID 43486067.

- Schwertner Harvey A; Vítek Libor (May 2008). "Gilbert syndrome, UGT1A1*28 allele, and cardiovascular disease risk: possible protective effects and therapeutic applications of bilirubin". Atherosclerosis (Review). 198 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.01.001. PMID 18343383.

- Vítek L; Jirsa M; Brodanová M; et al. (2002). "Gilbert syndrome and ischemic heart disease: a protective effect of elevated bilirubin levels". Atherosclerosis. 160 (2): 449–56. doi:10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00601-3. PMID 11849670.

- Lin JP; O’Donnell CJ; Schwaiger JP; et al. (2006). "Association between the UGT1A1*28 allele, bilirubin levels, and coronary heart disease in the Framingham Heart Study". Circulation. 114 (14): 1476–81. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.633206. PMID 17000907.

- Kundur, Avinash R.; Singh, Indu; Bulmer, Andrew C. (March 2015). "Bilirubin, platelet activation and heart disease: a missing link to cardiovascular protection in Gilbert's syndrome?". Atherosclerosis. 239 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.042. ISSN 1879-1484. PMID 25576848.

- GilbertsSyndrome.com Archived 2006-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Olsson R, Bliding A, Jagenburg R, Lapidus L, Larsson B, Svärdsudd K, Wittboldt S (1988). "Gilbert's syndrome—does it exist? A study of the prevalence of symptoms in Gilbert syndrome". Acta Medica Scandinavica. 224 (5): 485–490. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1988.tb19615.x. PMID 3264448.

- Bailey A, Robinson D, Dawson AM (1977). "Does Gilbert's disease exist?". Lancet. 1 (8018): 931–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(77)92226-7. PMID 67389. S2CID 41989158.

- Larissa K. F. Temple; Robin S. McLeod; Steven Gallinger; James G. Wright (2001). "Defining Disease in the Genomics Era". Science Magazine. 293 (5531): 807–808. doi:10.1126/science.1062938. PMID 11486074. S2CID 6520035.

- del Giudice EM, Perrotta S, Nobili B, Specchia C, d'Urzo G, Iolascon A (October 1999). "Coinheritance of Gilbert syndrome increases the risk for developing gallstones in patients with hereditary spherocytosis". Blood. 94 (7): 2259–62. doi:10.1182/blood.V94.7.2259.419k42_2259_2262. PMID 10498597. S2CID 40558696. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.

- "Gilbert Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- "Gilbert syndrome: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- "Gilbert's syndrome - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- "Entrez Gene: UGT1A1 UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, polypeptide A1". Archived from the original on 2010-12-05.

- Raijmakers MT, Jansen PL, Steegers EA, Peters WH (2000). "Association of human liver bilirubin UDP-glucuronyltransferase activity, most commonly due to a polymorphism in the promoter region of the UGT1A1 gene". Journal of Hepatology. 33 (3): 348–351. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80268-8. PMID 11019988.

- Bosma PJ; Chowdhury JR; Bakker C; Gantla S; de Boer A; Oostra BA; Lindhout D; Tytgat GN; Jansen PL; Oude Elferink RP; et al. (1995). "The genetic basis of the reduced expression of bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 in Gilbert's syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 333 (18): 1171–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM199511023331802. PMID 7565971.

- Monaghan G, Ryan M, Seddon R, Hume R, Burchell B (1996). "Genetic variation in bilirubin UPD-glucuronosyltransferase gene promoter and Gilbert's syndrome". Lancet. 347 (9001): 578–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91273-8. PMID 8596320. S2CID 24943762.

- J L Gollan; C Bateman; B H Billing (1976). "Effect of dietary composition on the unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia of Gilbert's syndrome". Gut. 17 (5): 335–340. doi:10.1136/gut.17.5.335. PMC 1411132. PMID 1278716.

- N Carulli; M Ponz de Leon; E Mauro; F Manenti; A Ferrari (1976). "Alteration of drug metabolism in Gilbert's syndrome". Gut. 17 (8): 581–587. doi:10.1136/gut.17.8.581. PMC 1411334. PMID 976795.

- Jens Einar Meulengracht at Who Named It?

- Foulk, WT; Butt, HR; Owen, CA Jr; Whitcomb, FF Jr; Mason, HL (1959). "Constitutional hepatic dysfunction (Gilbert's disease): its natural history and related syndromes". Medicine (Baltimore). 38 (1): 25–46. doi:10.1097/00005792-195902000-00002. PMID 13632313. S2CID 8265932.

- Shmaefsky, Brian (2006). "5". Biotechnology 101. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 175. ISBN 978-0-313-33528-0.

- "Wire preaches delights of three cliffs". South Wales Evening Post. 2007-04-27. p. 3.

- David Cox. (19 April 2014). "A Tennis Player Learns to Be Aggressive for Health's Sake". New York Times. Monte Carlo. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016.

- Khorounzhiy, Valentin (2017-11-09). "Illness that 'shut down' Tech3 MotoGP rookie Jonas Folger diagnosed". Autosport.com. Motorsport Network. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

After visiting specialists in his native Germany, Folger has been diagnosed with Gilbert's syndrome – a genetic ailment that precludes the liver from correctly processing bilirubin.

External links

- Understanding Gilbert's Syndrome and living better with Gilbert's Syndrome symptoms

- Gilbert's syndrome at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases

- Gilbert's Syndrome BMJ Best Practices monograph