J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913)[1] was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known as J.P. Morgan and Co., he was the driving force behind the wave of industrial consolidation in the United States spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

J. P. Morgan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | John Pierpont Morgan April 17, 1837 Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | March 31, 1913 (aged 75) |

| Resting place | Cedar Hill Cemetery Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Founding J.P. Morgan & Co. and International Mercantile Marine Co-founding General Electric; International Harvester; and U.S. Steel Organizing the Morgan "money trust" which dominated Aetna, General Electric, International Mercantile Marine Company, Pullman Palace Car Company, U.S. Steel, Western Union, and 21 railroads |

| Board member of | Northern Pacific Railway, New Haven Railroad, Pennsylvania Railroad, Pullman Palace Car Company, Western Union, New York Central Railroad, Albany & Susquehanna Railroad, Aetna, General Electric and U.S. Steel |

| Spouses | Amelia Sturges

(m. 1861; died 1862)Frances Louise Tracy

(m. 1865) |

| Children | 4; including Jack and Anne |

| Parent |

|

| Family | Morgan |

| Signature | |

Over the course of his career on Wall Street, Morgan spearheaded the formation of several prominent multinational corporations including U.S. Steel, International Harvester, and General Electric. He and his partners also held controlling interests in numerous other American businesses including Aetna, Western Union, Pullman Car Company, and 21 railroads.[2] Due to the extent of his dominance over U.S. finance, Morgan exercised enormous influence over the nation's policies and the market forces underlying its economy. During the Panic of 1907, he organized a coalition of financiers that saved the American monetary system from collapse.

As the Progressive Era's leading financier, Morgan's dedication to efficiency and modernization helped transform the shape of the American economy.[1] Adrian Wooldridge characterized Morgan as America's "greatest banker".[3] Morgan died in Rome, Italy, in his sleep in 1913 at the age of 75, leaving his fortune and business to his son, John Pierpont Morgan Jr. Biographer Ron Chernow estimated his fortune at $80 million (equivalent to $2.4 billion in 2022).[4]

Childhood and education

Morgan was born on April 17, 1837, in Hartford, Connecticut, to Junius Spencer Morgan (1813–1890) and Juliet Pierpont (1816–1884) of the influential Morgan family. His father, Junius, was a partner at Howe Mather & Co., the largest dry goods wholesaler in Hartford. His mother Juliet was the daughter of the poet John Pierpont.

Morgan preferred to be called "Pierpont", as opposed to "John".[5] He had a varied education due in part to his father's plans. In 1847, when Morgan was ten years old, his grandfather Joseph Morgan died and left a large fortune to Junius Spencer Morgan, who soon became a senior partner at the rechristened Mather Morgan & Co.[6] In the fall of 1848, the young Morgan transferred to the Hartford Public School, then to the Episcopal Academy in Cheshire, Connecticut, where he boarded with the principal.

In September 1851, he passed the entrance exam for The English High School of Boston, which specialized in mathematics for careers in commerce. In April 1852, rheumatic fever struck Morgan, an illness whose symptoms became more common as his life progressed and left him in such pain that he could not walk. Junius sent him to the Azores to recover. He convalesced there for almost a year, then returned to Boston to resume his studies.[7]

After graduation, his father sent him to Bellerive, a school in the Swiss village of La Tour-de-Peilz, where he gained fluency in French. His father then sent him to the University of Göttingen to improve his German. He attained passable fluency and a degree in art history within six months, completing his studies in 1857.[8]

J.S. Morgan & Co.: 1858–1871

After studying at Göttingen and thus completing his education, Morgan went to London in August 1857 to join his father, now a partner in the merchant banking firm George Peabody & Co.[lower-alpha 1][9] For the next fourteen years, he worked as his father's American representative in a series of affiliate banking houses, learning the trade and lifestyle of a bank partner: Duncan, Sherman & Company (1858–60), his own firm J. Pierpont Morgan & Co. (1860–64), and finally Dabney Morgan (1864–72).

Morgan quickly moved on to New York City to begin work at Duncan Sherman as a junior clerk.[10] Through his father's reputation and his position as the obvious successor to the Peabody house, he was quickly among the most sought-after young men on Wall Street and enjoyed the company of many of New York's leading citizens.[10]

Morgan had a great deal of independence in both his investment decisions and lifestyle, owing partly to his father's faith in Morgan's austere religious discipline. "Remember," J.S. Morgan wrote his son, "that there is an Eye above that is ever upon you and that for every act, word, and deed you will one day be called to give account."[10] He adopted a serious, energetic approach to his work and was praised by his father's friends for his work ethic and capacity for business.[10]

Duncan, Sherman & Company: 1858–1861

At the time Morgan entered the firm, Peabody & Co. was struggling in the wake of the Panic of 1857, a rash of business failures which dramatically hurt investor confidence in American securities. Peabody & Co., whose business was focused on American trade and enterprise, was particularly threatened; a few of its American correspondents were forced to suspend operations.[9] The house's creditors, including Baring Brothers, demanded payment; Peabody defied them, daring his rivals to put him out of business, and turned to the Bank of England for a loan in November 1857. Morgan himself expressed surprise that the famed Barings house was not more accommodating.[9] The loan secured the house's survival and the London office was stabilized, but Duncan Sherman came under criticism on Wall Street, and the Mercantile Agency recommended its dissolution. J. P. Morgan urged his father to stand by Duncan Sherman in the face of "outrageous" reports "of Browns & Barings getting the credit for what they never did."[9]

While at Duncan Sherman, Morgan gained early experience in the financing and reorganization of railroads, including the major Ohio & Mississippi and Illinois Central lines, for which he personally negotiated the loans. Most of his work involved collecting and transmitting interest and dividend payments, executing orders on the New York Stock Exchange, and conducting credit checks on mercantile houses doing business with Peabody & Co.[11][10]

Starting in early January 1859, Morgan spent several months in the South to visit the firm's correspondents in Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana and to improve his knowledge of the cotton trade.[12] He briefly visited Cuba, where he developed a lifelong taste for Cuban cigars.[10] Most of his time in the South was spent in New Orleans, a leading cotton export hub. He received a stern warning from Duncan Sherman when he conducted an unauthorized trade of coffee at a profit, which he considered his first totally independent transaction.[10] Later that summer, he visited his father in London. They discussed the prospects of Morgan going into business for himself, and Morgan courted Amelia Sturges, whom he later married.[10]

J. Pierpont Morgan & Co.: 1861–1864

As the American Civil War began, business slowed, delaying Morgan's efforts to open his own office.[10] He opened J. Pierpont Morgan & Company some time between April and July 1861,[10] conducting operations out of a one-room office at 53 Exchange Place. As he anticipated, most of his business was for his father and consistent with the work he had managed at Duncan Sherman.[13] Morgan avoided serving during the war by paying a substitute $300 to take his place.[14]

In 1862, Morgan made his cousin, James Goodwin, a partner. The firm received a serious boost when Morgan's father succeeded George Peabody as head of the London office. J.S. Morgan transferred all of the London office's remaining commercial credit and securities accounts from Duncan Sherman, and by the end of 1862, J. Pierpont Morgan & Co. was considered one of the stronger private banking houses on Wall Street.[14]

The Civil War radically altered Morgan's focus by virtually eliminating his cotton business and drastically reducing iron imports for American railroads in favor of securities and foreign exchange operations.[14] The Morgans, trading through J. P.'s New York office, made a large profit in the purchase and sale of Union bonds, especially after the Battle of Antietam turned the war in the Union's favor.[15] Morgan also profited in gold after specie payments were suspended in 1862; its price was largely pegged to the possibility of a Union victory. In October 1863, he and Edward B. Ketchum transferred $1.15 million (equivalent to $20,287,000 in 2021) in gold to England, forcing a price spike and allowing both men to sell their holdings at a large profit. Critics have long considered the deal a speculative effort to corner the American gold market and evidence of Morgan's insensitivity to the nation's financial situation, although the economic consequences were ultimately minor.[16]

Hall Carbine Affair

In August 1861, Morgan lent $20,000 (equivalent to $483,140 in 2021) to Simon Stevens, a well-connected New York City attorney and former secretary to Thaddeus Stevens. Stevens used the money to purchase five thousand carbines for resale to General John C. Frémont, commander of the Department of the West.[17] The carbines in question were developed by John H. Hall and manufactured by Simeon North, purchased by the U.S. government, and resold to arms dealer Arthur M. Eastman for $3.50 apiece in June 1861 (equivalent to $114 in 2022). After the Union defeat at Bull Run placed a premium on arms, Stevens used the Morgan loan to purchase the rifles from Eastman at $11.50 apiece and immediately resold them to Frémont, a longtime acquaintance, at $22 each.[17]

During the loan's thirty-eight day duration, Morgan held title to the carbines and assumed responsibility for having their barrels replaced with spirally grooved ones before shipment to Frémont. Stevens approached Morgan for another loan, which Morgan refused, instead asking Stevens for the $20,000 on the original loan and attempting to remove himself from the transaction. On September 14, Morgan received $55,000 from the Army for the carbines, deducted the face value of the loan plus expenses and interest, and passed the remainder to Stevens.[17]

By September, when Morgan received payment, the deal was already controversial. Military officials felt Frémont had overpaid, and an 1863 House of Representatives report indicted the profiteers as "worse than traitors in arms." Though Morgan was neither criticized nor censured during contemporary investigations, his name remained connected with the Hall Carbine Affair for many years.

Debate over Morgan's knowledge and involvement became a cause célèbre within his lifetime, attracting a wide range of commentary; debate over his involvement and knowledge has persisted long after his death.[18][19] Interest in Morgan's role in the affair was rekindled in 1910 with the publication of Gustavus Myers' History of the Great American Fortunes.[20] Myers claimed the rifles were more likely to blow the rifleman's thumb off than they were to cause any damage to the enemy. An earlier version of the carbine rifle was known to be subject to this problem.[19] R. Gordon Wasson, later the head of public relations for J.P. Morgan & Co., argued that there was no evidence Morgan knew that he was participating in a scheme to profit.[18] Vincent Carosso, author of an academic history of the Morgan house, concurs that Stevens "used Morgan's name" to cover his greed and that "none of the evidence suggested that Morgan himself had been a party to the shabby contract or had participated in its profits," though he "failed to exercise the care and caution that he had demonstrated two years earlier in the New Orleans coffee deal."[17] Matthew Josephson, who popularized the term "robber baron," asserted that Morgan certainly did know of the scheme, because he had presented the government with a bill for $58,175 before he delivered the remaining rifles that were being held as collateral.[21] Reviewing the evidence, Charles Morris also concluded that it was "implausible" that Morgan did not know about the source of his profits.[22]

Dabney, Morgan & Co.: 1864–1872

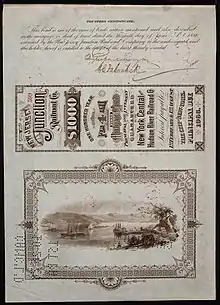

From 1864 to 1872, he was a member of the firm of Dabney, Morgan, & Co. In 1869, He wrested control of the Albany and Susquehanna Railroad from Jay Gould and Jim Fisk.

Drexel Morgan & Co.: 1871–1895

In 1871, at the behest of J.S. Morgan, the Philadelphia financier Anthony Joseph Drexel became J. P.'s mentor. They formed Drexel Morgan & Co.[23] This new merchant banking partnership, based in New York, served as an agent for European investment in the United States and assumed the leading role in financing America's railroads and stabilizing and revitalizing American securities markets. The firm created a national capital market for industrial companies, which had previously existed only for railroads and canals. Drexel Morgan also played an important role in government finance. To restore investor confidence, Drexel Morgan underwrote the pay of the entire U.S. Army in 1877 and bailed out the U.S. government during the Panic of 1895.[24] The foundation of Drexel Morgan and their partnership with Anthony Drexel also established Morgan family offices in London (J.S. Morgan), Philadelphia, New York City (Dabney Morgan), and Paris (Drexel Harjes), which would subsequently become J.P. Morgan & Co.

After his father's death in 1890, Morgan took control of J. S. Morgan & Co.

Railroad investments and management

In his ascent to power, Morgan focused on America's largest business enterprises: railroads.[25] He led the syndicate that broke the government-financing privileges of Jay Cooke and developed and financed a national railroad empire by reorganization and consolidation. He raised large sums in Europe. Rather than participating solely as a financier, he actively managed and reorganized the railroad corporations, increasing efficiency[26] and acting as an early pioneer in the practice of private equity investing, a process that became known as "Morganization".[27]

In 1883, Morgan successfully marketed a large part of William H. Vanderbilt's New York Central holdings. In 1885, he reorganized the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railroad and leased it to the New York Central.[28] In 1886, he reorganized the Philadelphia & Reading, and in 1888, the Chesapeake & Ohio.

In 1887, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act. Morgan set up industry conferences in 1889 and 1890 which paved the way for a wave of consolidations in the early 20th century. In an unprecedented move, he brought together railroad presidents to follow the new laws and write agreements for the maintenance of "public, reasonable, uniform and stable rates". The first of their kind, the conferences created a community of interest among competing lines, paving the way for the great consolidations of the early 20th century.[29][30]

Morgan also financed street railways, especially in New York City.

J.P. Morgan & Company: 1895–1913

After the death of Anthony Drexel, the firm was renamed J. P. Morgan & Company in 1895, retaining close ties with Drexel & Company of Philadelphia; Morgan, Harjes & Company of Paris; and J.S. Morgan & Company (after 1910 Morgan, Grenfell & Company) of London. By 1900 it was one of the world's most powerful banking houses, focused primarily on reorganizations and consolidations.

Morgan had many partners over the years, such as George Walbridge Perkins, but always remained firmly in charge.[31] His international reputation as a financier began to draw investors to the businesses that he took over.[32]

Panic of 1893 and election of 1896

At the depths of the Panic of 1893, around 1895, the U.S. Treasury nearly depleted its gold reserves. Morgan put forward a plan for the federal government to buy gold from his and European banks, but it was declined in favor of a plan to sell government bonds directly to the general public. Morgan demanded a meeting with President Grover Cleveland, where he claimed the United States government could default that day if action was not taken.

Morgan came up with a plan to use an old civil war statute that allowed Morgan and the Rothschilds to sell 3.5 million ounces[33] of gold directly to the U.S. Treasury in exchange for a 30-year bond issue.[34] The episode saved the Treasury but hurt Cleveland's standing with the populist agrarian wing of the Democratic Party, ensuring his political career was over. In the 1896 United States presidential election, bankers came under a withering attack from William Jennings Bryan, and Morgan was among many who donated heavily to Republican William McKinley.[35]

Nikola Tesla's Wardenclyffe station: 1900

In 1900, the inventor Nikola Tesla convinced Morgan he could build a trans-Atlantic wireless communication system based on his theories of Earth and atmospheric electrical conduction (eventually sited at Wardenclyffe) that would outperform the short range radio wave-based wireless telegraph system then being demonstrated by Guglielmo Marconi. In what may have been a philanthropic investment,[36] Morgan gave Tesla $150,000 (equivalent to $5,276,400 in 2022) to build the system and Tesla offered him a 51% control of the patents. Almost as soon as the letter of agreement was signed Tesla decided to scale up the facility to include his ideas of terrestrial wireless power transmission to make what he thought was a more competitive system.[37] Morgan refused to give Tesla any further money towards the project and, with Tesla unable to secure further investment capital, Wardenclyffe's development stalled and the site was abandoned by 1906.[37][38]

Northern Securities: 1901–1904

The Northern Pacific Railway went bankrupt in the Panic of 1893. The bankruptcy wiped out the railroad's bondholders, leaving it free of debt, and a complex financial battle for its control ensued. In 1901, a compromise was reached between Morgan, New York financier E. H. Harriman and Minnesota railroad builder James J. Hill. To reduce competition in the Midwest, they created the Northern Securities Company to merge three of the region's most important railways: the Northern Pacific Railway, the Great Northern Railway, and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad. The parties ran into unexpected opposition from President Theodore Roosevelt, who considered the merger bad for consumers and a violation of the seldom-enforced Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. In 1902, Roosevelt ordered Attorney General Philander Knox to sue to break it up. In 1904, the Supreme Court dissolved the Northern Security company; though Morgan did not lose money, his all-powerful political reputation suffered.[39][40][41][42]

U.S. Steel: 1901–1913

In 1900, Morgan began talks to purchase Andrew Carnegie's steel business and merge it with several other steel, coal, mining and shipping firms. After financing the creation of the Federal Steel Company, Morgan merged it with the Carnegie Steel Company and several other steel and iron businesses (including William Edenbirn's Consolidated Steel and Wire Company) in 1901, forming the United States Steel Corporation. U.S. Steel was the world's first billion-dollar company, with an authorized capitalization of $1.4 billion, much larger than any other industrial firm and comparable in size to the largest railroads.

U.S. Steel's goals were to achieve greater economies of scale, reduce transportation and resource costs, expand product lines, and improve distribution to allow the United States to compete globally with the United Kingdom and Germany.[43] U.S. Steel president Charles M. Schwab and others claimed the company's size would enable it to be more aggressive and effective in pursuing distant international markets.[43] Critics regarded U.S. Steel as a monopoly, as it sought to dominate not only steel but the construction of bridges, ships, railroad cars, rails, wire, nails, and many other products. With U.S. Steel, Morgan captured two-thirds of the steel market, and Schwab was confident that the company would soon hold a 75% market share.[43] However, its market share dropped. In 1903, Schwab resigned to form Bethlehem Steel, which became the second largest U.S. steel producer.

U.S. Steel also faced criticism for its labor policies. U.S. Steel was non-union and used aggressive tactics to identify and root out pro-union "troublemakers." The lawyers and bankers who had organized the merger, including Morgan, were more concerned with long-range profits, stability, good public relations, and avoiding trouble. His views generally prevailed, and the result was a "paternalistic" labor policy.[31]

Failed London Underground line: 1902

Morgan suffered a rare business defeat in 1902 when he attempted to build and operate a line on the London Underground. Transit magnate Charles Tyson Yerkes thwarted Morgan's effort to obtain parliamentary authority to build the Piccadilly, City and North East London Railway, a subway line that would have competed with "tube" lines controlled by Yerkes.[44] Morgan called Yerkes' coup "the greatest rascality and conspiracy I ever heard of".[45]

International Mercantile Marine and RMS Titanic: 1902–1913

In 1902, J.P. Morgan & Co. financed the formation of International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMMC), an Atlantic shipping company which absorbed several major American and British lines in an attempt to monopolize the shipping trade. Morgan hoped to dominate transatlantic shipping through interlocking directorates and contractual arrangements with the railroads, but that proved impossible because of the unscheduled nature of sea transport, American antitrust legislation, and an agreement with the British government.

Morgan had a private suite and promenade deck on the RMS Titanic and scheduled to sail on the ill-fated maiden voyage of the ship, which was owned by an IMMC subsidiary, White Star Line, but those plans were later changed.[46][47] The ship's famous sinking was a financial disaster for IMMC. Analysis of financial records shows that IMMC was over-leveraged and suffered from inadequate cash flow causing it to default on bond interest payments.[lower-alpha 2][48][49]

In response to the sinking, Morgan purportedly said:

Monetary losses amount to nothing in life. It is the loss of life that counts. It is that frightful death.[50]

Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907 was a financial crisis that almost crippled the American economy. Major New York banks were on the verge of bankruptcy and there was no mechanism to rescue them, until Morgan stepped in to help resolve the crisis.[51][52] To ease the crisis, Secretary of the Treasury George B. Cortelyou earmarked $35 million of federal money to deposit in New York banks.[53] Morgan then met with the nation's leading financiers in his New York mansion, where he forced them to devise a plan to meet the crisis. James Stillman, president of the National City Bank, also played a central role. Morgan organized a team of bank and trust executives which redirected money between banks, secured further international lines of credit, and bought up the plummeting stocks of healthy corporations.[51]

A delicate issue arose regarding the brokerage firm of Moore and Schley, which was deeply invested in the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI). Moore and Schley had used over $6 million of TCI stock as collateral for loans to Wall Street banks, which the firm now could not pay. If Moore and Schley failed, it could precipitate a larger crisis. Thus, Morgan proposed merging the TCI with U.S. Steel, one of its chief competitors.

U.S. Steel president Elbert Gary agreed, but was concerned that antitrust implications could obstruct the merger. Morgan sent Gary to see President Theodore Roosevelt, who promised legal immunity for the deal. U.S. Steel thereupon paid $30 million for the TCI stock and Moore and Schley was saved. The announcement had an immediate effect; by November 7, 1907, the panic was over.[51]

The crisis underscored the need for a powerful oversight mechanism, and in 1913, banking and political leaders, led by Senator Nelson Aldrich, devised a plan that resulted in the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

Criticisms and investigations

While conservatives hailed Morgan for civic responsibility, strengthening the national economy, and devotion to the arts and religion, critics of banking and consolidation viewed him as one of the leading figures in the system they rejected.[55][56] They attacked Morgan for the terms of his 1895 loan of gold to the U.S. Treasury. Many, including writer Upton Sinclair, attacked him for his handling of the Panic of 1907. They also blamed him for the financial ills of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad.

In December 1912, Morgan testified before the Pujo Committee, a subcommittee of the House Banking and Currency committee. The committee ultimately concluded that a small number of financial leaders was exercising considerable control over many industries. The partners of J.P. Morgan & Co. and directors of First National and National City Bank controlled aggregate resources of $22.245 billion, which Louis Brandeis compared to the value of all the property in the twenty-two states west of the Mississippi River.[57]

Investigation by historian James Lide discovered that through parts of its business, JPMorgan Chase accepted thousands of slaves as collateral on loans made to plantation owners in the early 19th century, and that it ended up owning several hundred slaves.[58] The banks in question, Citizens' Bank and Canal Bank, both now part of JPMorgan, served plantations from the 1830s until the American Civil War, and sometimes took ownership of slaves when the plantation owners defaulted on loans. JPMorgan estimated that between 1831 and 1865, the two banks accepted approximately 13,000 slaves as collateral and ended up owning about 1,250 slaves. An apology was made in compliance with a rule requiring companies to detail past dealings with the slave trade when doing business with the city of Chicago.[59][60]

List of Morgan corporations

From 1890 to 1913, 42 major corporations were organized or their securities were underwritten, in whole or part, by J.P. Morgan and Company.[61]

Manufacturing and construction industry

- Aetna Inc.

- American Bridge Company

- American Can Company

- American Telephone & Telegraph

- Atlas Portland Cement Company

- Boomer Coal & Coke

- Consolidated Edison

- DuPont

- Federal Steel Company

- General Electric

- General Motors

- Hartford Carpet Corporation

- Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company

- International Harvester

- International Mercantile Marine

- International Telephone & Telegraph

- J. I. Case Threshing Machine

- Kennecott Copper

- National Tube

- Montgomery Ward

- Pullman Car Company

- United Dry Goods

- United States Steel Corporation

- Western Union

Railroads

- Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway

- Atlantic Coast Line

- Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

- Central of Georgia Railway

- Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

- Chicago and Western Indiana Railroad

- Chicago, Burlington and Quincy

- Chicago Great Western Railway

- Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railroad

- Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railway

- Erie Railroad

- Florida East Coast Railway

- Great Northern Railway

- Hocking Valley Railway

- Jersey Central Railroad

- Lehigh Valley Railroad

- Louisville and Nashville Railroad

- New York Central System

- New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad

- New York, Ontario and Western Railway

- New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway

- Nickel Plate Road

- Northern Pacific Railway

- Pennsylvania Railroad

- Pere Marquette Railroad

- Reading Railroad

- St. Louis–San Francisco Railway

- Southern Railway

- Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis

Personal life

Marriages and children

In October 1861, Morgan married Amelia "Memi" Sturges (1835–1862) at her home on 5 East Fourteenth Street. He had courted her for two years, and when they married, Memi was already seriously ill with tuberculosis. Morgan had to carry her to the drawing room for a small private ceremony and afterwards to the carriage which took them to the pier. They travelled to Algiers, where he hoped the warm climate would restore their health, but it did not, and she died in Nice in February 1862, four months and ten days after their marriage.[62]

He then married Frances Louisa "Fanny" Tracy (1842–1924), on May 31, 1865. They had four children:

- Louisa Pierpont Morgan (1866–1946), who married Herbert L. Satterlee (1863–1947)[63]

- J. P. Morgan Jr. (1867–1943), who succeeded his father and married Jane Norton Grew

- Juliet Pierpont Morgan (1870–1952), who married William Pierson Hamilton (1869–1950)

- Anne Tracy Morgan (1873–1952), philanthropist

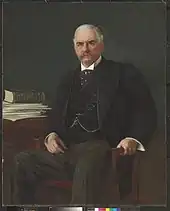

Appearance

Morgan often had a tremendous physical effect on people; one man said that a visit from Morgan left him feeling "as if a gale had blown through the house."[4] He was physically large with massive shoulders, piercing eyes, and a purple nose.[64] He was known to dislike publicity and hated being photographed without his permission; as a result of his self-consciousness of his rosacea, all of his professional portraits were retouched.[65] His deformed nose was due to a disease called rhinophyma, which can result from rosacea. As the deformity worsens, pits, nodules, fissures, lobulations, and pedunculation contort the nose. This condition inspired the crude taunt "Johnny Morgan's nasal organ has a purple hue."[66] Surgeons could have shaved away the rhinophymous growth of sebaceous tissue during Morgan's lifetime, but as a child he suffered from infantile seizures, and Morgan's son-in-law, Herbert L. Satterlee, has speculated that he did not seek surgery for his nose because he feared the seizures would return.[67]

His social and professional self-confidence were too well established to be undermined by this affliction. It appeared as if he dared people to meet him squarely and not shrink from the sight, asserting the force of his character over the ugliness of his face.[68]

Morgan smoked dozens of cigars per day and favored large Havana cigars dubbed Hercules' Clubs by observers.[69]

Religion

Morgan was a lifelong member of the Episcopal Church, and by 1890 was one of its most influential leaders.[70] He was a founding member of the Church Club of New York, an Episcopal private member's club in Manhattan.[71] Morgan was appointed as one of the first laymen on the committee that created the 1892 revision of the Book of Common Prayer, where he petitioned for the creation of a special limited collectible printing that he later financed.[72] In 1910, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church established a commission, proposed by Bishop Charles Brent, to implement a world conference of churches to address their differences in their “faith and order.” Morgan was so impressed by the proposal for such a conference that he contributed $100,000 (equivalent to $2,125,100 in 2021) to finance the commission's work.[73]

Residences

His house at 219 Madison Avenue was originally built in 1853 by John Jay Phelps and purchased by Morgan in 1882.[74] It became the first electrically lit private residence in New York. His interest in the new technology was a result of his financing Thomas Alva Edison's Edison Electric Illuminating Company in 1878.[75] It was there that a reception of 1,000 people was held for the marriage of Juliet Morgan and William Pierson Hamilton on April 12, 1894, where they were given a favorite clock of Morgan's. Morgan also owned the "Cragston" estate, located in Highland Falls, New York. His son, of the same name, was the owner of East Island in Glen Cove, New York.

J. P. Morgan spent three months of every year in London and owned two houses there. His 'town' house, 13 Prince's Gate was inherited from his father and was later expanded by the acquisition of the neighbouring Number 14 to house his growing art collection. After his death the merged houses were offered to the US government for use as the residence of the US Ambassador, from 1929 to 1955. His other property was Dover House, Putney, which was later demolished and developed into the Dover House Estate.

Social organizations and philanthropy

Morgan was a member of the Union Club in New York City. When a friend, Erie Railroad president John King, was blackballed, Morgan resigned and organized the Metropolitan Club of New York.[76] He donated the land on 5th Avenue and 60th Street at a cost of $125,000, and commanded Stanford White to "...build me a club fit for gentlemen, forget the expense..."[55] He invited King in as a charter member and served as club president from 1891 to 1900.[77]

Morgan was a benefactor of the Morgan Library and Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, Groton School, Harvard University (especially its medical school), Trinity College, the Lying-in Hospital of the City of New York, and the New York trade schools.

Yachting

Morgan was the Commodore of the New York Yacht Club (NYYC) and was present at a board meeting on October 27, 1898, to discuss the construction of a new clubhouse. Morgan offered to acquire a 75-by-100-foot (23 by 30 m) plot on 44th Street in midtown Manhattan [78][79] if the NYYC raised its annual membership dues from $25 to $50 and the new clubhouse occupied the entire site.[79] The NYYC's board accepted his offer, and Morgan bought the lots the next day for $148,000 and donated to the club.[80][81]

NYYC members hosted an informal housewarming party on January 29, 1901, giving Morgan a trophy in gratitude of his purchase of the site.[82][83]

An avid yachtsman, Morgan owned several large yachts, the first being the Corsair, built by William Cramp & Sons for Charles J. Osborn (1837–1885) and launched on May 26, 1880. Charles J. Osborn was Jay Gould's private banker. Morgan bought the yacht in 1882.[84] The well-known quote, "If you have to ask the price, you can't afford it" is commonly attributed to Morgan in response to a question about the cost of maintaining a yacht, although the story is unconfirmed.[85] A similarly unconfirmed legend attributes the quote to his son, J. P. Morgan Jr., in connection with the launching of the son's yacht Corsair IV at Bath Iron Works in 1930.

Collections

Morgan was a collector of books, pictures, paintings, clocks and other art objects, many loaned or given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (of which he was president and a major force in its establishment), and many housed in his London house and in his private library on 36th Street, near Madison Avenue in New York City.

For a number of years the British artist and art critic Roger Fry worked for the museum, and in effect for Morgan, as a collector.[86]

His son, J. P. Morgan Jr., made the Pierpont Morgan Library a public institution in 1924 as a memorial to his father, and appointed Belle da Costa Greene, his father's private librarian, as its first director.[87]

Gems

By the turn of the century, Morgan had become one of America's most important collectors of gems and had assembled the most important gem collection in the U.S. as well as of American gemstones (over 1,000 pieces). Tiffany & Co. assembled his first collection under their Chief Gemologist, George Frederick Kunz. The collection was exhibited at the World's Fair in Paris in 1889. The exhibit won two golden awards and drew the attention of important scholars, lapidaries, and the general public.[88]

George Frederick Kunz continued to build a second, even finer, collection which was exhibited in Paris in 1900. These collections have been donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where they were known as the Morgan-Tiffany and the Morgan-Bement collections.[89] In 1911 Kunz named a newly found gem after his best customer morganite.

Photography

Morgan was a patron to photographer Edward S. Curtis, offering Curtis $75,000 in 1906 (equivalent to $1,730,560 in 2021) to create a series on the American Indians.[90] Curtis eventually published a 20-volume work entitled The North American Indian.[91] Curtis also produced a motion picture, In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914), which was restored in 1974 and re-released as In the Land of the War Canoes. Curtis was also famous for a 1911 magic lantern slide show The Indian Picture Opera which used his photos and original musical compositions by composer Henry F. Gilbert.[92]

Death

Morgan died while traveling abroad on March 31, 1913, in his sleep at the Grand Hotel Plaza in Rome, Italy. His body was brought back to America aboard the SS France, a French Line passenger ship.[93] Flags on Wall Street flew at half-staff, and in an honor usually reserved for heads of state, the stock market closed for two hours when his body passed through New York City.[94] His body was brought to lie in his home and adjacent library the first night of arrival in New York City. His remains were interred in the Cedar Hill Cemetery in his birthplace of Hartford, Connecticut. His son, John Pierpont "Jack" Morgan Jr., inherited the banking business.[95] His estate was worth $68.3 million ($1.39 billion in today's dollars based on CPI, or $25.2 billion based on share of GDP), of which about $30 million represented his share in the New York and Philadelphia banks. The value of his art collection was estimated at $50 million.[96]

Legacy

His son, J. P. Morgan Jr., took over the business at his father's death, but he was never as influential. The 1933 Glass–Steagall Act forced the dissolution of the House of Morgan into three entities:

- J.P. Morgan & Co., which later became Morgan Guaranty Trust

- Morgan Stanley, an investment house formed by his grandson Henry Sturgis Morgan

- Morgan Grenfell in London, an overseas securities house

The gemstone morganite was named in his honor.[97]

The Cragston Dependencies, associated with his estate, Cragston (at Highlands, New York), was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.[98]

He bequeathed his mansion and large book collections to the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.

Popular culture

- A contemporary literary biography of Morgan is used as an allegory for the financial environment in America after World War I in the second volume, Nineteen Nineteen, of John Dos Passos' U.S.A. trilogy.

- Morgan appears as a character in Caleb Carr's novel The Alienist,[99] in E. L. Doctorow's novel Ragtime,[100] in Steven S. Drachman's novel The Ghosts of Watt O'Hugh,[101] in Graham Moore's novel The Last Days of Night,[102] and in Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray's novel The Personal Librarian.[103]

- Morgan is believed to have been the model for Walter Parks Thatcher (played by George Coulouris), guardian of the young Citizen Kane (film directed by Orson Welles) with whom he has a tense relationship—Kane blaming Thatcher for destroying his childhood.[104]

- According to Phil Orbanes, former vice president of Parker Brothers, the Rich Uncle Pennybags of the American version of the board game Monopoly is modeled after J. P. Morgan.[105] The family of the illustrator Daniel Fox, who in 1936 created the mascot for the game, have credited J. P. Morgan as being the inspiration for the character.[106]

- Morgan's career is highlighted in episodes three and four of the History Channel's The Men Who Built America.[107]

- "My Name Is Morgan (But It Ain't J.P.)" – 1906 popular song released as an Edison cylinder recording, with words by Will A. Mahoney, music by Halsey K. Mohr, and sung by Bob Roberts. Originally released as a "coon song" but revised over the years, a poor man named Morgan tells his girlfriend not to mistake him for a rich man.[108][109]

- The villain of Street Fighter 6 is an elderly upper-class banker that uses a variety of aliases, all of which have the initials "JP." He claims to have lived for over one hundred years, empowered by his business association with M. Bison

See also

- Ventfort Hall Mansion and Gilded Age Museum

- SS J. Pierpont Morgan, a lake freighter named after Morgan

Notes

- The firm was later renamed J.S. Morgan & Co. upon George Peabody's retirement in 1864.

- After Morgan's death, the IMMC was forced to apply for bankruptcy protection in 1915. Its fortunes were saved by World War I, and it eventually re-emerged as the United States Lines, which went bankrupt in 1986.

References

- "J.P. Morgan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Ward, Geoffrey C.; Burns, Ken (2014). The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-307-70023-0.

- Adrian Wooldridge (September 15, 2016). "The alphabet of success". The Economist. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "John Pierpont Morgan and the American Corporation". Biography of America. Archived from the original on May 22, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- "Pierpont Morgan: Banker". The Morgan Library & Museum. March 12, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- Carosso 1987, p. 26.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 31–32.

- "JP Morgan biography – One of the most influential bankers in history". Financial-inspiration.com. March 31, 1913. Archived from the original on October 16, 2005. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 63–67.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 83–91.

- Carosso 1987, p. 78.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 87–88.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 91–92.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 95–97.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 98–100.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 101–03.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 92–94.

- Wasson, R. Gordon (1943). The Hall Carbine Affair: A Study in Contemporary Folklore. Pandick Press.

- "U.S. Carbine Model 1843 Breechloading Percussion Hall-North .52". Springfield Armory Museum collection record. Springfield Armory Museum. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- Myers, Gustavus (1910). History of the Great American Fortunes, V. 3. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr. pp. 146–176.

- Josephson, Matthew (1934). The Robber Barons (Mariner Books 1962 ed.). Harcourt, Brace & Co. pp. 61ff. ISBN 978-0-15-676790-3.

- Morris 2006, p. 337.

- Rottenberg 2006, p. 98.

- Rottenberg (2006), p. .

- Strouse 1999, pp. 223–62.

- Mall, Scott (October 21, 2021). "FreightWaves Classics/Leaders: J.P. Morgan controlled US railroads and industry policies". FreightWaves. Retrieved January 26, 2023.

Morgan's first target was the U.S. railroad industry, which will be the focus of this FreightWaves Classics article. He began by taking over small underfinanced companies, streamlined their management and operational efficiency, and then combined the companies into a dominant player.

- Timmons, Heather (November 18, 2002). "J.P. Morgan: Pierpont would not approve". BusinessWeek.

- Albro Martin, Albro. "Crisis of Rugged Individualism: The West Shore-South Pennsylvania Railroad Affair, 1880-1885." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 93.2 (1969): 218-243. online Archived November 14, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Carosso 1987, pp. 219–69.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 352–96.

- Garraty 1960, p. .

- "Morganization: How Bankrupt Railroads were Reorganized". Archived from the original on March 14, 2006. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- The value of the gold would have been approximately $72 million at the official price of $20.67 per ounce (equal to $727 today) at the time. "Historical Gold Prices – 1833 to Present"; National Mining Association; retrieved December 22, 2011.

- "J.P. Morgan: Biography". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- Gordon, John Steele (Winter 2010). "The Golden Touch" at the Wayback Machine (archived July 2, 2010), American Heritage.com; retrieved December 22, 2011; archived from the original on July 10, 2010.

- Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla, Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton University Press, page 317

- Seifer, Marc J. (2006). "Nikola Tesla: The Lost Wizard". ExtraOrdinary Technology. 4 (1).

- Cheney, Margaret (2001). Tesla: Man Out of Time. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 203–208. ISBN 0-7432-1536-2.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 478–79.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 529–30.

- Strouse 1999, pp. 418–33.

- Strouse 1999, p. 515.

- Krass, Peter (May 2001). "He Did It! (creation of U.S. Steel by J.P. Morgan)". Across the Board (Professional Collection).

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. pp. 157–158. ISBN 1-85414-293-3.

- Franch, John (2006). Robber Baron: The Life of Charles Tyson Yerkes. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 298. ISBN 0-252-03099-0.

- Chernow 2001, p. 146.

- Steven H. Gittelman, J.P. Morgan and the Transportation Kings: The Titanic and Other Disasters, University Press of America, 2012, pages 286-287

- Clark & Clark 1997.

- Steven H. Gittelman, J. P. Morgan and the Transportation Kings: The Titanic and Other Disasters (Lanham: University Press of America, 2012).

- Daugherty, Greg (March 2012). "Seven Famous People who missed the Titanic". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Carosso 1987, pp. 528–48.

- Bruner & Carr 2007, p. .

- Fridson, Martin S. (1998). It Was a Very Good Year: Extraordinary Moments in Stock Market History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 6. ISBN 9780471174004. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- Burgan 2007, p. 93.

- Strouse 1999, p. .

- Morris 2006, p. .

- Brandeis 1914, ch. 2.

- JOURNAL, Robin SidelStaff Reporter of THE WALL STREET (May 10, 2005). "A Historian's Quest Links J.P. Morgan To Slave Ownership". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- Moore, Jamillah (June 30, 2022). "JP Morgan Bank Slavery Disclosure" (PDF). City of Philadelphia. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Janssen, Claudia I. (January 2012). "Addressing Corporate Ties to Slavery: Corporate Apologia in a Discourse of Reconciliation". Communication Studies. 63 (1): 18–35. doi:10.1080/10510974.2011.627974. ISSN 1051-0974. S2CID 30404803.

- Meyer Weinberg, ed. America's Economic Heritage (1983) 2: 350.

- Carosso 1987, p. 94.

- Satterlee 1939, p. .

- Gross 2009, p. 69.

- Brands 2010, p. 70.

- Kennedy, David M., and Lizabeth Cohen; The American Pageant; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, 2006. p. 541.

- Strouse 1999, p. 265.

- Strouse 1999, pp. 265–66.

- Chernow 2001, p. .

- Hein & Shattuck 2005, p. .

- "History". The Church Club of New York. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- "The Evolution of the Standard Prayer Book of 1892". The Independent. 1893. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- Heather A. Warren, Religion in America: Theologians of a New World Order: Rheinhold Niebuhr and the Christian Realists, 1920-1948 (Oxford University Press, 1997), pg. 16.

- "J. P. Morgan Home, 219 Madison Avenue". Digital Culture of Metropolitan New York. Digital Culture of Metropolitan New York is a service of the Metropolitan New York Library Council. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- Chernow 2001, ch. 4.

- "The Epic of Rockefeller Center". TODAY.com. September 30, 2003. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- "J. P. Morgan". Philanthropy Roundtable. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- "Yachting: Commodore Morgan Gives the New-york Club a Site for a House to Race for the Canadian Cup Yacht Associations Meet". New-York Tribune. October 28, 1898. p. 4. ProQuest 574511646.

- "Commodore Morgan's Gift; Presents Three Lots to the N.Y. Yacht Club for a New Home". The New York Times. October 28, 1898. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- "New Yacht Club House; Commodore Morgan Buys a 75-Foot Frontage in Forty-fourth Street for a Site". The New York Times. October 29, 1898. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- "Com Morgan Pays $148,000.: Loses No Time in Making Good His Offer to Provide Site for New Clubhouse for New York Yacht Club". Boston Daily Globe. October 29, 1898. p. 5. ProQuest 498954045.

- "N.Y.Y.C. Honors J.P. Morgan: Silver Loving Cup Presented to the Club's Ex-commodore". The New York Times. January 30, 1901. p. 7. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 1013633831.

- "Harriman Gets Chicago Lines.: Terminal Transfer Company's Stock Reported in Control of Eastern Man. Details of the Deal. Charity Ball for Benefit of Nursery and Childs' Hospital a Success. General New York News". Chicago Tribune. January 30, 1901. p. 5. ProQuest 173095798.

- "Yacht Corsair". Spirit of the Times. May 29, 1880. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- Business Education World, Vol. 42. Gregg Publishing Company. 1961. p. 32.

- Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry: A Biography, London, the Hogarth Press, 1940

- Auchincloss 1990, p. .

- Morgan and His Gem Collection; George Frederick Kunz: Gems and Precious Stones of North America, New York, 1890, accessed online February 20, 2007.

- Morgan and His Gem Collections; donations to AMNH; in George Frederick Kunz: History of Gems Found in North Carolina, Raleigh, 1907, accessed online February 20, 2007.

- "Biography". Edward S. Curtis. Seattle: Flury & Company. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- "Digital Collections - Libraries - Northwestern University". dc.library.northwestern.edu.

- "The Indian Picture Opera—A Vanishing Race". Archived from the original on March 11, 2007.

- The Only Way to Cross by John Maxtone-Graham

- Modern Marvels episode "The Stock Exchange" originally aired on October 12, 1997.

- "Cedar Hill Cemetery". August 27, 2006. Archived from the original on August 27, 2006.

- Chernow 2001, ch. 8.

- Morganite, International Colored Gemstone Association, accessed online January 22, 2007.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Carr, Caleb (1994). The Alienist. Random House. ISBN 9780679417798.

- Doctorow, E. L. (1975). Ragtime. Random House. ISBN 9780394469010.

- Drachman, Steven S. (2011). The Ghosts of Watt O'Hugh. pp. 2, 17–28, 33–34, 70–81, 151–159, 195. ISBN 9780578085906.

- Moore, Graham (2016). The Last Days of Night. Random House.

- Benedict, Marie (2021). The Personal Librarian. Berkley. ISBN 978-0593101537.

- "Citizen Kane (1941)". Filmsite.org. May 1, 1941. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- Association of Game and Puzzle Collectors Quarterly www.AGPC.ORG summer 2013 Vol.15 No. 2. Page 18. Meet Daniel Gidahlia Fox - The Artist Who Created "Mr. Monopoly" by Emily F.Clements.

- Turpin, Zachary. "Interview: Phil Orbanes, Monopoly Expert (Part Two)". Book of Odds. Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- "The Men Who Built America > The History Channel Club". September 30, 2012. Archived from the original on September 30, 2012.

- Cass Canfield, The Incredible Pierpont Morgan: financier and art collector; Harper & Row (1974), p. 125

- David A. Jasen, A Century of American Popular Music, Routledge, October 15, 2013, page 142

Sources

- Auchincloss, Louis (1990). J.P. Morgan: The Financier as Collector. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-3610-0.

- Bruner, Robert F.; Carr, Sean D. (2007). The Panic of 1907: Lessons Learned from the Market's Perfect Storm.

- Brandeis, Louis (1914). Other People's Money and How the Bankers Use It. New York: Frederic A. Stokes Company.

- Brands, H.W. (2010). American Colossus: The Triumph of Capitalism, 1865–1900. New York: Anchor Books.

- Burgan, Michael (2007). J. Pierpont Morgan: Industrialist and Financier. Capstone.

- Carosso, Vincent P. (1987). The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854–1913. Harvard Univ. Press. p. 888. ISBN 978-0-674-58729-8.

- Chernow, Ron (2001). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. ISBN 0-8021-3829-2.

- Clark, John J.; Clark, Margaret T. (1997). "The International Mercantile Marine Company: A Financial Analysis". American Neptune. 57 (2): 137–154.

- Garraty, John A. (1960). "The United States Steel Corporation Versus Labor: the Early Years". Labor History. 1 (1): 3–38. doi:10.1080/00236566008583839.

- Gross, Michael (2009). Rogues' Gallery: The Secret History of the Moguls and the Money That Made the Metropolitan Museum. New York: Broadway Books. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7679-2488-7. OCLC 244417339.

- Hein, David; Shattuck, Gardiner H. Jr. (2005). The Episcopalians. Westport: Praeger.

- Morris, Charles (2006). The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. New York: Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8050-8134-3.

- Rottenberg, Dan (2006). The Man Who Made Wall Street: Anthony J. Drexel and the Rise of Modern Finance. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 98. ISBN 9780812219661. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- Satterlee, Herbert L. (1939). J. Pierpont Morgan. New York: The Macmillan Company., written by Morgan's son-in-law

- Strouse, Jean (1999). Morgan, American Financier. Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-095589-2.

Further reading

| Library resources about J. P. Morgan |

| By J. P. Morgan |

|---|

Biographies

Specialized studies

- Carosso, Vincent P. Investment Banking in America: A History Harvard University Press (1970)

- De Long, Bradford. "Did JP Morgan's Men Add Value?: An Economist's Perspective on Financial Capitalism," in Peter Temin, ed., Inside the Business Enterprise: Historical Perspectives on the Use of Information (1991) pp. 205–36; shows firms with a Morgan partner on their board had higher stock prices (relative to book value) than their competitors

- Forbes, John Douglas. J. P. Morgan Jr. 1867–1943 (1981). 262 pp. biography of his son

- Fraser, Steve. Every Man a Speculator: A History of Wall Street in American Life HarperCollins (2005)

- Garraty, John A. Right-Hand Man: The Life of George W. Perkins. (1960) ISBN 978-0-313-20186-8; Perkins was a top aide 1900–1910

- Geisst; Charles R. Wall Street: A History from Its Beginnings to the Fall of Enron. Oxford University Press. 2004.

- Giedeman, Daniel C. "J. P. Morgan, the Clayton Antitrust Act, and Industrial Finance-Constraints in the Early Twentieth Century", Essays in Economic and Business History, 2004 22: 111–126

- Hannah, Leslie. "J. P. Morgan in London and New York before 1914," Business History Review 85 (Spring 2011) 113–50

- Keys, C.M. (January 1908). "The Builders I: The House of Morgan". The World's Work. Vol. 15, no. 2. pp. 9779–9704. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- Moody, John. The Masters of Capital: A Chronicle of Wall Street (1921)

Other

- Baker, Ray Stannard (October 1901). "J. Pierpont Morgan". McClure's Magazine. Vol. 17, no. 6. pp. 507–518. Retrieved July 10, 2009., a biographical magazine article

- Brands, H.W. (1999). Masters of Enterprise: Giants of American Business from John Jacob Astor and J. P. Morgan to Bill Gates and Oprah Winfrey., including a short biography of Morgan

External links

- The Morgan Library and Museum, 225 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

- The American Experience—J.P. Morgan

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- . The Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1918.

- "Morgan, John Pierpont". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Morgan, John Pierpont". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.