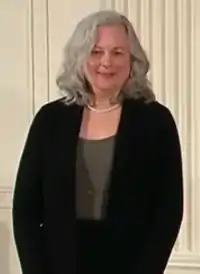

Judith Klinman

Judith P. Klinman (born April 17, 1941, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)[1] is an American chemist, biochemist, and molecular biologist known for her work on enzyme catalysis. She became the first female professor in the physical sciences at the University of California, Berkeley in 1978,[2][3] where she is now Professor of the Graduate School and Chancellor's Professor.[4] In 2012, she was awarded the National Medal of Science by President Barack Obama.[5] She is a member of the National Academy of Sciences,[6] American Academy of Arts and Sciences,[7] American Association for the Advancement of Science,[8] and the American Philosophical Society.[9]

Judith Pollock Klinman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 17, 1941 |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Pennsylvania A.B. (1962), Ph.D. (1966) |

| Awards | National Medal of Science (2012) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry Chemistry |

| Institutions | University of California at Berkeley |

| Thesis | A Kinetic Study of the Hydrolysis and Imidazole-Catalyzed Hydrolysis of Substituted Benzoyl Imidazole in Light and Heavy Water (1966) |

| Doctoral advisor | Edward R. Thornton |

| Doctoral students | Natalie Ahn |

| Website | www |

Early life

Klinman was born April 17, 1941, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[1] When Klinman was two years old, her biological father left the family.[2] Klinman's mother sold her house and possessions and moved with Klinman to Miami Beach, Florida, for a time, before returning to Philadelphia to find work.[10] Klinman's mother then remarried, and so she was raised by her mother and stepfather.[2] Neither her mother nor stepfather graduated from college, but her stepfather attended Drexel University for two years but dropped out due to the Great Depression, and later found work selling furniture.[2] Klinman was initially interested in ballet, but her interest in chemistry was piqued by her high school chemistry teacher.[2] She received a partial scholarship from her high school, Overbrook High School, to attend college, graduating second in her class.[2] Klinman decided to enroll in the University of Pennsylvania's College for Women, despite pressure from her family to become a lab technician and get married.[2]

Education and training

Beginning in 1958, Klinman studied chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn).[10] While in college, Klinman was a laboratory technician at the Eldridge R. Johnson Foundation for Research in Medical Physics at UPenn. She graduated with her A.B. in Chemistry in 1962.[1] Klinman applied to medical and graduate school, and received acceptances to both.[2] In 1962, Klinman enrolled in the Chemistry graduate program at New York University (NYU).[2] Klinman credits her time at NYU for "opening [her] eyes to the excitement and beauty of organic reaction mechanisms."[10] After a year in New York City, she moved back to Philadelphia, and enrolled at UPenn for graduate studies.[2] Working in the laboratory of physical organic chemist Prof. Edward R. Thornton, Klinman studied the hydrolysis kinetics of benzyl-substituted imidiazoles.[11] She graduated with her Ph.D. in 1966.[12]

In 1966, Klinman travelled to the Weizmann Institute in Israel to conduct postdoctoral research with Prof. David Samuel.[2] She worked in the Isotopes Department, which had a large supply of heavy water that could be used for kinetic studies. Klinman's work with Samuel involved understanding the role of divalent metal ions in the hydrolysis of high-energy acyl phosphates.[13] While in Israel, Klinman survived the Six-Day War of 1967.[2][10] She and her then husband, Norman R. Klinman, left Israel in 1967, as her husband was conducting postdoctoral studies at the National Institute for Medical Research in Mill Hill, London.[10][14] Klinman arranged a nonpaying apprenticeship at University College London (UCL) in the laboratory of Charles A. Vernon, and also took courses in biochemistry at UCL.

Klinman and her husband returned to the United States in 1968, and Klinman took up a position as a postdoctoral associate at the Institute for Cancer Research (ICR), a part of the Fox Chase Cancer Research Institute.[10][15] There, she joined the laboratory of Irwin Rose, where she investigated the mechanism of aconitate isomerase, an enzyme that catalyzes the cis-trans isomerism of aconitate.[16][17] Klinman also studied the stereochemical products of ATP citrate lyase and citrate synthase.[18]

Independent career

In 1972, Klinman was promoted to an independent staff scientist, equivalent to an Assistant Professorship, at the Institute for Cancer Research.[10] In 1974, she joined the University of Pennsylvania as an Assistant Professor of Biophysics.[19]

In 1978, she moved to University of California, Berkeley as an Associate Professor in Chemistry,[15] the first female faculty member in the physical sciences at UC Berkeley.[20] She is currently the Professor of the Graduate School at the Departments of Chemistry and Molecular and Cell Biology and the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences at the University of California, Berkeley.[12] She also served the Chancellor's Professor for University of California Berkeley.[21][22] She currently serves as the Professor of the Graduate School.[23]

Her group has discovered that room temperature hydrogen tunneling occurs among various enzymatic reactions, such as enzymatic C-H cleavage,[10] and clarified the dynamics of tunneling process through data analysis. They have also discovered the quino-enzymes, a new class of redox cofactors in eukaryotic enzymes.[24][25]

Honors and awards

- 1988 Guggenheim Fellowship[26]

- 1992 and 2003-4 Miller Professorship, University of California, Berkeley.[27]

- 1993 Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[7]

- 1994 Elected to the National Academy of Sciences[6]

- 1994 Repligen Award for Chemistry of Biological Processes.[28]

- 1995 Alexander M. Cruickshank Lecturer[29]

- 1996 Fellow of the Japanese Ministry of Science[19]

- 2000 Honorary Doctorate (F.D.(h.c.)) from the University of Uppsala, Sweden.[30]

- 2001 Elected to the American Philosophical Society[9]

- 2003 David S. Sigman Lectureship Award from UCLA.[31]

- 2005 Remsen Award, Maryland Section of the American Chemical Society[32]

- 2006 Honorary Doctorate (Sc.D.(h.c.)) from the University of Pennsylvania[33]

- 2007 Elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science[8]

- 2007 Merck Award from the American Society of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology[34]

- 2009 Elected to the Royal Society of Chemistry[19]

- 2011 Elected to the American Chemical Society[19][35]

- 2012 A. I. Scott Medal for Excellence in Biological Chemistry Research, Texas A&M University.[19][36]

- 2014 National Medal of Science.[37][38]

- 2015 Mildred Cohn Award in Biological Chemistry from the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.[39]

- 2017 Willard Gibbs Award from the Chicago Section of the American Chemical Society[40]

- 2018 Penn Chemistry Distinguished Alumni Award, University of Pennsylvania[41]

Personal life

Judith Klinman was married to Norman R. Klinman, who later became a Professor of Immunology and Microbial Science at The Scripps Research Institute.[14] The two met at the University of Pennsylvania, and were married while Klinman was completing her Ph.D.[2][10] They had two children together, Andrew and Douglas.[2][10] Andrew was born while Klinman was in graduate school (born 1964-1966), and Douglas when she was a postdoctoral scholar at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel (born in 1967).[2][10] She and Norman divorced in 1978, at the time of her laboratory's move to UC Berkeley.[2][10]

Judith Klinman later married Mordechai Mitnick, a grassroots organizer who later established a psychotherapy practice in Oakland.[10][42][43][44] They raised four children together: Alexandra, Joshua, Andrew, and Douglas, and have eight grandchildren.[10]

Klinman has a stepsister, who as of 2002 worked for the Small Business Administration.[2]

Videos

- 2012 - National Medals of Science (National Science & Technology Medals Foundation)

- 2014 - Thriving in Science Lecture: "Not Going It Alone"

- 2018 - NSF/JHU Quantum Biology and Quantum Processes in Biology Workshop - "Tunneling in Biology"

- 2020 - Interviewing Eminent Scientists - Prof. Judith Klinman

- 2022 - G.N. Lewis Lecture - "At the Interface of Quantum and Classical Behavior in Enzyme Catalysis"

References

- "Judith P. Klinman CV" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-06. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- Zanish-Belcher, Tanya (June 13, 2002). "Judith P. Klinman Oral History (Interview with Judith Klinman)". cdm16001.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- "Berkeley's First Women Chemists". Catalyst Magazine. 2018-05-01. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- "Judith P. Klinman | College of Chemistry". chemistry.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- "The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details | NSF - National Science Foundation". www.nsf.gov. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- "Judith P. Klinman". Archived from the original on 2018-02-07. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Klinman, Judith". 5 August 2016. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org.

- Klinman, Judith P. (2019). "Moving Through Barriers in Science and Life". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 88 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111217. PMC 6956981. PMID 31220975.

- Klinman, Judith Pollock; Thornton, Edward R. (1968-07-01). "Solvolysis mechanisms. A kinetic study of the hydrolysis and imidazole-catalyzed hydrolysis of p-methyl-, p-chloro-, and p-nitrobenzoylimidazole in H2O and of p-nitrobenzoylimidazole in deuterium oxide". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 90 (16): 4390–4394. doi:10.1021/ja01018a034. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Latham, J. A.; Barr, I.; Klinman, J. P. (2017). "Author profile: Judith P. Klinman". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 292 (40): 16397–16405. doi:10.1074/jbc.R117.797399. PMC 5633103. PMID 28830931. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- Klinman, Judith P.; Samuel, David (1971-05-01). "Oxygen-18 studies to determine the position of bond cleavage of acetyl phosphate in the presence of divalent metal ions". Biochemistry. 10 (11): 2126–2131. doi:10.1021/bi00787a026. ISSN 0006-2960. PMID 4327401.

- "TSRI - News & Views, In Memoriam: Norman R. Klinman". www.scripps.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- "NSTMF". NSTMF. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- Klinman, Judith P.; Rose, Irwin A. (1971-06-08). "Purification and kinetic properties of aconitate isomerase from Pseudomonas putida". Biochemistry. 10 (12): 2253–2259. doi:10.1021/bi00788a011. ISSN 0006-2960. PMID 5114987.

- Klinman, Judith P.; Rose, Irwin A. (1971-06-08). "Mechanism of the aconitate isomerase reaction". Biochemistry. 10 (12): 2259–2266. doi:10.1021/bi00788a012. ISSN 0006-2960. PMID 5114988.

- Klinman, Judith P.; Rose, Irwin A. (1971-06-08). "Stereochemistry of the interconversions of citrate and acetate catalyzed by citrate synthase, adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase, and citrate lyase". Biochemistry. 10 (12): 2267–2272. doi:10.1021/bi00788a013. ISSN 0006-2960. PMID 5165527.

- "Judith P. Klinman Curriculum Vitae" (PDF). Department of Chemistry, University of California Berkeley. 2020-01-29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-06. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- "ASBMB Past Presidents". Archived from the original on 2014-07-13. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- "The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details | NSF - National Science Foundation". www.nsf.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "Judith Klinman | F1000 Faculty Member | F1000Prime". f1000.com. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "Judith P. Klinman | College of Chemistry". chemistry.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "The first women chemistry scientists at Cal - College of Chemistry". chemistry.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-02-08.

- "Judith Klinman". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "Judith P. Klinman". Archived from the original on 2018-02-07. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- "All Miller Professors: By Name". Archived from the original on 2015-08-22. Retrieved 2015-08-29.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-07-17. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Gordon Research Conferences - Alexander M. Cruickshank Awards". archive.fo. 4 August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- "Honorary Doctors of the Faculty of Science and Technology - Uppsala University, Sweden". www.uu.se. Archived from the original on 2018-02-06.

- "Sigman Symposium – Molecular Biology Institute". Archived from the original on 2018-02-06. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- "Remsen Award - Maryland Section". Archived from the original on 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- "Honorary Degree Recipients | Penn Secretary". secure.www.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-02-07.

- "ASBMB–Merck Award". Archived from the original on 2016-12-29. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- "2011 ACS Fellows". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "A. I. Scott Medal - Department of Chemistry - Texas A&M University". www.chem.tamu.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-02-06.

- "President Obama honors nation's top scientists and innovators". nsf.gov. National Science Foundation (NSF) News. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06.

- "Judith Klinman". Archived from the original on 2016-05-30. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- "Mildred Cohn Award in Biological Chemistry". American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "2017 Gibbs Awardee, Judith Klinman 'C-H activation, quantum tunneling, and new ways of looking at enzyme catalysis'". Chicago Section American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 2017-08-23.

- "Distinguished Alumni Award | Department of Chemistry". www.chem.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- Mannervik, Bengt (2012-02-24). "Five Decades with Glutathione and the GSTome". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (9): 6072–6083. doi:10.1074/jbc.X112.342675. ISSN 0021-9258. PMC 3307307. PMID 22247548.

- "Mordechai Mitnick". Presence Therapy. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- Today, Psychology. "Mordechai Mitnick, Clinical Social Work/Therapist, Oakland, CA, 94618". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2021-05-24.