Lace

Lace is a delicate fabric made of yarn or thread in an open weblike pattern,[1] made by machine or by hand. Generally, lace is divided into two main categories, needlelace and bobbin lace,[2]: 122 although there are other types of lace, such as knitted or crocheted lace. Other laces such as these are considered as a category of their specific craft. Knitted lace, therefore, is an example of knitting. This article considers both needle lace and bobbin lace.

While some experts say both needle lace and bobbin lace began in Italy in the late 1500s,[2]: 122 [3]: 12 there are some questions regarding its origins.

Originally linen, silk, gold, or silver threads were used. Now lace is often made with cotton thread, although linen and silk threads are still available. Manufactured lace may be made of synthetic fiber. A few modern artists make lace with a fine copper or silver wire instead of thread.

Etymology

The word lace is from Middle English, from Old French las, noose, string, from Vulgar Latin *laceum, from Latin laqueus, noose; probably akin to lacere, to entice or ensnare.[1]

Description

The Latin word from which lace is derived means "noose," and a noose describes an open space outlined with rope or thread. This description applies to many types of open fabric resulting from "looping, plaiting, twisting, or knotting...threads...by hand or machine."[2]: 122

Types

There are many types of lace, classified by how they are made. These include:

- Bobbin lace, as the name suggests, is made with bobbins and a pillow. The bobbins, turned from wood, bone, or plastic, hold threads which are woven together and held in place with pins stuck in the pattern on the pillow. The pillow contains straw, preferably oat straw or other materials such as sawdust, insulation styrofoam, or ethafoam. Also known as bone-lace. Chantilly lace is a type of bobbin lace.

- Chemical lace: the stitching area is stitched with embroidery threads that form a continuous motif. Afterwards, the stitching areas are removed and only the embroidery remains. The stitching ground is made of a water-soluble or non-heat-resistant material.

- Crocheted lace includes Irish crochet, pineapple crochet, and filet crochet.

- Cutwork, or whitework, is lace constructed by removing threads from a woven background, and the remaining threads wrapped or filled with embroidery.

- Knitted lace includes Shetland lace, such as the "wedding ring shawl", a lace shawl so fine that it can be pulled through a wedding ring.[4]

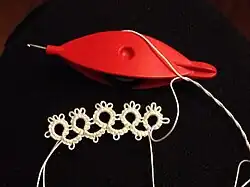

- Knotted lace includes macramé and tatting. Tatted lace is made with a shuttle or a tatting needle.

- Machine-made lace is any style of lace created or replicated using mechanical means.

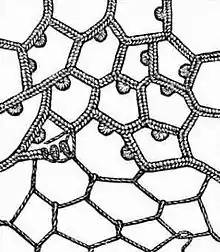

- Needle lace, such as Venetian Gros Point, is made using a needle and thread. This is the most flexible of the lace-making arts. While some types can be made more quickly than the finest of bobbin laces, others are very time-consuming. Some purists regard needle lace as the height of lace-making. The finest antique needle laces were made from a very fine thread that is not manufactured today.

- Tape lace makes the tape in the lace as it is worked, or uses a machine- or hand-made textile strip formed into a design, then joined and embellished with needle or bobbin lace.

Needle lace, showing button hole stitch

Needle lace, showing button hole stitch Bobbin lace made on a pillow with bobbins and pins

Bobbin lace made on a pillow with bobbins and pins.jpg.webp) Broderie anglaise, a type of cutwork

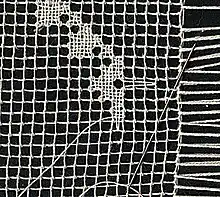

Broderie anglaise, a type of cutwork Filet lace, embroidered on an existing net

Filet lace, embroidered on an existing net

Tatting, with shuttle

Tatting, with shuttle

History: Bobbin and needle lace

Origins

The origin of lace is disputed by historians. An Italian claim is a will of 1493 by the Milanese Sforza family.[6] A Flemish claim is lace on the alb of a worshiping priest in a painting about 1485 by Hans Memling.[7] But since lace evolved from other techniques, it is impossible to say that it originated in any one place.[8] The fragility of lace also means that few exceedingly old specimens are extant.[9]: 3

Early history

Lace was used by clergy of the early Catholic Church as part of vestments in religious ceremonies. When they first started to use lace and through the 16th century, they primarily used cutwork. Much of their lace was made of gold, silver, and silk. Wealthy people began to use such expensive lace in clothing trimmings and furnishings such as cushion covers. In the 1300s and 1400s in the Italian states heavy duties were imposed on lace, and strict sumptuary laws were passed.[10]: 6–7 This led to less demand for lace. In the mid-1400s some lacemakers turned to using flax, which cost less, while others migrated, bringing the industry to other countries. However, lace did not come into widespread use until the 16th century in the northwestern part of the European continent.[11] The popularity of lace increased rapidly and the cottage industry of lace making spread throughout Europe.The late 16th century marked the rapid development of lace, both needle lace and bobbin lace became dominant in both fashion as well as home décor. For enhancing the beauty of collars and cuffs, needle lace was embroidered with loops and picots.[12] Sumptuary laws in many countries had a major impact on lace wearing and production throughout its early history, though in some countries they were often ignored or worked around.[10]: 9–10

Italy

Bobbin and needle lace were both being made in Italy early in the 1400s.[13]: 19 Documenting lace in Italy in the 15th century is a list of fine laces from the inventory of Beatrice d'Este, Duchess of Milan, from 1493.[14]

Venice

In Venice, lace making was originally the province of leisured noblewomen, using it as a pastime. Some of the wives of doges also supported lacemaking in the Republic. One, Giovanna Malipiero Dandolo, showed support in 1457 for a law protecting lacemakers. In 1476, the lace trade was seriously affected by a law which disallowed "silver and embroidery on any fabric and the Punto in Aria of linen threads made with a needle, or gold and silver threads."[10]: 10 In 1595, Morosina Morosini, another doge's wife, founded a lace workshop for 130 women.[15]: 403 In the early 1500s, the production of lace became a paid activity, accomplished by young girls working in the houses of noblewomen, creating lace for household use, and in convents. Lace was a popular Venetian export in the 1500s and 1600s, and the demand remained strong in Europe, even when the export of other items exported by Venice during this period slumped.[15]: 406 The largest and most intricate pieces of Venetian lace became ruffs and collars for members of the nobility and for aristocrats.[15]: 412

Belgium

Lace was being made in Brussels in the 1400s, and samples of such lace survive.[13]: 27 Belgium and Flanders became a major center for the creation of primarily bobbin lace starting in the 1500s, and some handmade lace is still being produced there today.[3]: 19, 31 Belgian-grown flax contributed to the lace industry in the country. It produced extremely fine linen threads that were a critical factor in the superior texture and quality of Belgian lace.[16]: 34 Schools were founded to teach lacemaking to the young.[3]: 31 The height of the production of lace there was in the 1700s. Brussels was known for Point d'Angleterre, Lierre and Bruges also were known for their own styles of lace. Belgian lacemakers either originated or developed laces such as Brussels or Brabant Lace, Lace of Flanders, Mechlin, Valenciennes and Binche.[3]: 19

France

Lace arrived in France when Catherine de Medici, newly married to King Henry II in 1533, brought Venetian lace-makers to her new homeland. The French royal court and the fashions popular there, influenced the lace that started to be made in France. It was delicate and graceful, compared to the heavier needle or point-laces of Venice. Examples of French lace are Alençon, Argentan, and Chantilly.[3]: 17 The 17th century court of King Louis the XIV of France was known for its extravagance, and during his reign lace, particularly the delicate Alençon and Argentan varieties, was extremely popular as court dress. The frontange, a tall lace headdress, became fashionable in France at this time. Louis XIV's finance minister, Jean Baptiste Colbert, strengthened the lace industry by establishing lace schools and workshops in the country.

Spain

Lacemaking in Spain was established early, as by the 1600s its Point d'Espagne lace, made of gold and silver thread, was very popular. Lace was made for use in churches and for the mantilla. Lacemaking may have come to Spain from Italy in the 1500s, or from Flanders, its province at the time.[13]: 33–35 This lace was much admired, and was made throughout the country.[17]: 117

Germany

Barbara Uttmann learned how to make bobbin lace as a girl from a Protestant refugee. In 1561 she started a lace-making workshop in Annaberg. By the time of her death in 1575, there were over 30,000 lacemakers in that area of Germany. Following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in France in 1685, many Huguenot lacemakers moved to Hamburg and Berlin. The earliest known lace pattern book was printed in Cologne in 1527.[13]: 30–31

England

The lace that was made in England prior to the introduction of bobbin lace in the mid 1500s was primarily cutwork or drawn thread work. There is a 1554 mention of Sir Thomas Wyatt wearing a ruff trimmed with bone lace (some bobbins at the time were made of bone).[18]: 49 The court of Queen Elizabeth of England maintained close ties with the French court, and so French lace began to be seen and appreciated in England. Lace was used on her court gowns, and became fashionable.

There are two distinct areas of England where lacemaking was a significant industry: Devon and part of the South Midlands.[18]: 48 Belgian lacemakers were encouraged to settle in Honiton in Devon at the end of the 16th century. They continued to make pillow and other lace, as they had in their homeland, but Honiton lace never got the acclaim that lace from France, Italy, and Belgium did.[3]: 19–21 While the lace in Devon stayed stable, in the lace-making areas of the South Midlands there were changes brought by different groups of émigrés: Flemings, French Huguenots, and later, French escaping the Revolution.[18]: 48–49

Catherine of Aragon, while exiled in Ampthill, England, was said to have supported the lace makers there by burning all her lace, and commissioning new pieces.[19] This may be the origin of the lacemaker's holiday, Cattern's Day. On this day (25 or 26 November) lacemakers were given a day off from work, and Cattern cakes - small dough cakes made with caraway seeds, were used to celebrate.[20] The English diarist Samuel Pepys often wrote about the lace used for his, his wife's, and his acquaintances' clothing, and on 10 May 1669, noted that he intended to remove the gold lace from the sleeves of his coat "as it is fit [he] should", possibly in order to avoid charges of ostentatious living.[21] In 1840, Britain's Queen Victoria was married in lace, influencing the wedding dress style until now.[22]

The decline of the lace industry in England began about 1780, as was happening elsewhere. Some of the reasons include the increased popularity of clothing in the Classical style, the economic issues connected to war, and the increased production and use of machine-made laces.[18]: 51–52

America

American colonists of both British and Dutch origins strove to acquire lace accessories such as caps, ruffs and other neckware, and handkerchiefs. Women who could afford it had these items as well as aprons and dresses trimmed or made entirely of lace. America also had sumptuary laws, such as one in Massachusetts in 1634 that did not allow citizens to own or make lace. This indicates that lace was being made in that colony at the time.[23]: 187–189 Lacemaking was being taught in boarding schools by the mid 1700s, and newspaper advertisements starting in the early 1700s offered to teach the technique.: 192 [23] Also in the 18th century, Ipswich, Massachusetts had become the only place in America known for producing handmade lace. By 1790, women in Ipswich, who were primarily from the British Midlands, were making 42,000 yards of silk bobbin lace intended for trimmings.[23]: 189–190 George Washington reportedly purchased Ipswich Lace on a trip to the region in 1789.[24] Machines to make lace began to be smuggled into the country in the early 1800s, as England did not permit these machines to be exported. The first lacemaking factory opened in Medway, Massachusetts in 1818. Ipswich had its own in 1824. The women there moved from making bobbin lace to decorating the machine-made net lace with darning and tambour stitches, creating what is known as Limerick lace.[23]: 190

Lace was still much in demand in the 19th century. Lace trimmings on dresses, at seams, pockets, and collars were very popular. The lace being made in the United States was based on European patterns. By the turn of the 20th century, needlework and other magazines included lace patterns of a range of types.[23]: 195

In North America in the 19th century, missionaries spread the knowledge of lace making to the Native American tribes.[25] Sibyl Carter, an Episcopalian missionary, began to teach lacemaking to Ojibwa women in Minnesota in 1890. Classes were being held for members of many tribes throughout the US by the first decade of the 1900s[23] St. John Francis Regis guided many women out of prostitution by establishing them in the lace making and embroidery trade, which is why he became the Patron Saint of lace making.[26]

Ireland

Lace was made in Ireland from the 1730s onwards with several different lace-making schools founded across the country. Many regions acquired a name for high-quality work and others developed a distinctive style. Lace proved to be an important means of income for many poorer women.[27] Several important schools of lace included: Carrickmacross lace, Kenmare lace, Limerick lace and Youghal lace.[28]

_School_-_Portrait_of_an_Unknown_Lady%252C_Aged_23_(called_%E2%80%98the_Countess_Miranda%E2%80%99)_-_1210350_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

_(style_of)_-_Portrait_of_an_Unknown_Gentleman_in_Brown_with_a_Lace_Collar_-_1336256_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

Patrons, designers, and lace makers

Patron saints

Some patron saints of lace include:[29]

Historic

- Giovanna Dandolo (1457–1462)

- Barbara Uthmann (1514–1575)

- Morosina Morosini (1545–1614)

- Federico de Vinciolo (16th century)

- Caterina Angiola Pieroncini (18th century)

Contemporary

Lace in art

The earliest portraits showing lace are those of the early Florentine School.[9]: 13 Later, in the 17th century, lace was very popular and painting styles were at the time realistic. This allows viewers to see the finery of lace.[30] Painted portraits, primarily those of the wealthy or the nobility, depicted costly laces. This presented a challenge to the painters, who needed to represent not only their sitters accurately, but their intricate lace as well.[15]: 414

The portrait of Nicolaes Hasselaer seen here was painted by Frans Hals in about 1627. It depicts a man dressed in a black garment with a lace collar. The collar is detailed enough that those who are expert in lace identification can tell what pattern it is. Hals created the lace effect with dabs of grey and white, using black paint to indicate the spaces between the threads.[31]

Lace is also mostly made out of machines now, and only very few people in the world practice lacing. It is an old practice that only a few can achieve.

An image of an anonymous female artisan appears in The Lacemaker, a painting by the Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), completed around 1669–1670.

See also

- Anglo Scotian Mills

- Doily

- Fishnet

- Lagetta lagetto (Lacebark)

- Lippitt Mill

- Ribbons

- Scranton Lace Company

- See-through clothing

Lace museums

- Fashion and Lace Museum, Brussels, Belgium

- Kantcentrum, Bruges, Belgium

- Kenmare Lace and Design Centre, Kenmare, Co. Kerry, Ireland

- The Lace Guild Museum and Gallery, Stourbridge, U.K.

- The Lace Museum, Sunnyvale, CA, US

- Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA, US

- Lace Museum/Museo del Merletto, near Venice, Italy

- Marès Lace Museum/Museu Marès de la Punta, Arenys de Mar, Spain

- Musée des Beaux-Arts et de la Dentelle Alençon, France

- Textilmuseum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland, and their exhibit traveled to Bard Graduate Center in 2022 for a major New York installation, Threads of Power.[32]

References

- "Lace". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Frost, Patricia (2000). Miller's collecting textiles. London. ISBN 1-84000-203-4. OCLC 48140446.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schwab, David E. (1957). The Story of Lace and Embroidery and Handkerchiefs. New York: Fairchild.

- Lovick, Elizabeth (2013). The Magic of Shetland Lace Knitting. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-250-03908-8.

- "Hans Memling | La Vierge et l'Enfant entre saint Jacques et saint Dominique". Site officiel du musée du Louvre (in French). 12 October 2023.

- Verhaegen, Pierre (1912). La Dentelle Belge (in French). Brussel: L. Lebègue. p. 10.

- van Steyvoort, Collette (1983). Inleiding to kantcreatie (Introduction to creating lace) (translation by Magda Grisar ed.). Paris: Dessain et Tolra. p. 11. ISBN 224927665X.

- "The Craft of Lacemaking". LaceGuild.org. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- Jackson, Emily (1987). Old handmade lace : with a dictionary of lace. Emily Jackson. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-25309-0. OCLC 14718956.

- Jackson, Mrs. F. Nevill (1900). A History of Hand-Made Lace. London: L. Upcott Gill.

- "History of Lace". www.lacemakerslace.oddquine.co.uk.

- "History of Lace | Lace Trends | Lace Spreads". Decoratingwithlaceoutlet.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Huetson, T. L. (1973). Lace and bobbins; a history and collector's guide ([1st American ed.] ed.). South Brunswick: A.S. Barnes. ISBN 0-498-01398-7. OCLC 793392.

- Singleton, Esther (1917). Lace and Lace Making. The Mentor.

- Jones, Ann Rosalind (2014). "Labor and Lace: The Crafts of Giacomo Franco's Habiti delle donne venetiane". I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance. 17 (2): 399–425. doi:10.1086/678268. ISSN 0393-5949. JSTOR 10.1086/678268. S2CID 192036554.

- Blum, Clara M. (1920). Old World Lace, or a Guide for the Lace Lover. New York: E.P. Dutton.

- Jones, Mary Eirwen (1951). The Romance of Lace. London: Staples.

- Mincoff, Elizabeth (1987). Pillow or bobbin lace : technique, patterns, history. Margaret S. Marriage. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-25505-0. OCLC 16527223.

- "St Catherine's Day, Cattern Cakes and Lace". Lavender and Lovage. 12 April 2017.

- Jones, Julia (1987). A Calendar of Feasts; Cattern cakes and lace. England: DK. ISBN 0863182526.

- Pepys, Samuel (10 May 1669). "Monday 10 May 1669". The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- The Fashion Book. London: Dorling Kindersley. 2014. p. 46. ISBN 9781409352327. OCLC 889544401.

- Weissman, Judith Reiter (1994). Labors of love : America's textiles and needlework, 1650-1930. Wendy Lavitt. New York: Wings Books. ISBN 0-517-10136-X. OCLC 29315818.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2021). Travels with George : in search of Washington and his legacy. [New York, New York]. ISBN 978-0-525-56217-7. OCLC 1237806867.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Indian Lace". 1 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013.

- "Society of Jesus Celebrates Feast of St. John Francis Regis, SJ". jesuits.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- Hooper, Glenn. "Irish Lace". Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- Potter, Matthew (2014). Amazing lace : a history of the Limerick lace industry. Jacqui Hayes. Limerick. ISBN 978-0-905700-22-9. OCLC 910526333.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Patron Saints of Needlework and Lace". Refresh. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- "The 10 Best Lace Paintings". Sophie Ploeg. 29 September 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Van Guldener, Hermine (1969). Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Munich: Knorr & Hirth Verlag. p. 27.

- Smith, Roberta (8 December 2022). "Lace, That Most Coveted Textile". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

.svg.png.webp)