Thai literature

Thai literature is the literature of the Thai people, almost exclusively written in the Thai language (although different scripts other than Thai may be used). Most of imaginative literary works in Thai, before the 19th century, were composed in poetry. Prose was reserved for historical records, chronicles, and legal documents. Consequently, the poetical forms in the Thai language are both numerous and highly developed. The corpus of Thailand's pre-modern poetic works is large.[1] Thus, although many literary works were lost with the sack of Ayutthaya in 1767, Thailand still possesses a large number of epic poems or long poetic tales [2]—some with original stories and some with stories drawn from foreign sources. There is thus a sharp contrast between the Thai literary tradition and that of other East Asian literary traditions, such as Chinese and Japanese, where long poetic tales are rare and epic poems are almost non-existent. The Thai classical literature exerted a considerable influence on the literature of neighboring countries in mainland Southeast Asia, especially Cambodia and Burma.

The development of Thai classical literature

Origins

As speakers of the tai language family, the Siamese share literary origins with other Tai speakers in mainland Southeast Asia. It is possible that the early literature of the Thai people may have been written in Chinese.[3][4] However, no historical record of the Siamese thus far refers to these earlier literature. The Thai poetical tradition was originally based on indigenous poetical forms such as rai (ร่าย), khlong (โคลง), kap (กาพย์), and klon (กลอน). Some of these poetical forms—notably Khlong - have been shared between the speakers of tai languages since ancient time (before the emergence of Siam). An early representative work of Khlong poetry is the epic poem Thao Hung Thao Cheuang, a shared epic story, about a noble warrior of a Khom race in mainland Southeast Asia.[5]

Indian influence on the Siamese language

Through Buddhism's and Hindu's influence, a variety of Chanda prosodic meters were received via Ceylon. Since the Thai language is mono-syllabic, a huge number of loan words from Sanskrit and Pali are needed to compose in these classical Sanskrit meters. According to B.J. Terwiel, this process occurred with an accelerated pace during the reign of King Boromma-trailokkanat (1448-1488) who reformed Siam's model of governance by turning the Siamese polity into an empire under the mandala feudal system.[6] The new system demanded a new imperial language for the ruling noble classes. This literary influence changed the course of the Thai or Siamese language—setting it apart from other tai languages—by increasing the number of Sanskrit and Pali words and imposing the demand on the Thai to develop a writing system that preserved the orthography of Sanskrit words for literary purposes. By the 15th century, the Thai language had evolved into a distinctive medium along with a nascent literary identity of a new nation. It allowed Siamese poets to compose in different poetical styles and mood—from playful and humorous rhymed verses, to romantic and elegant khlong and to polished and imperious chan prosodies which were modified from classical Sanskrit meters. Thai poets experimented with these different prosodic forms, producing innovative "hybrid" poems such as Lilit (Thai: ลิลิต—an interleave of khlong and kap or rai verses), or Kap hor Klong (Thai: กาพย์ห่อโคลง - a series of khlong poems each of which is enveloped by kap verses). The Thai thus developed a keen mind and a keen ear for poetry. To maximize this new literary medium, however, a rather intensive classical education in Pali and Sanskrit was required. This made "serious poetry" an occupation of the noble classes. However, B.J. Terwiel notes, citing a 17th-century Thai text book Jindamanee, that scribes and common Siamese men, too, were encouraged to learn basic Pali and Sanskrit terms for career advancement.[6]: 322–323 Thai poetry and literary production came to dominate the learned literature of the tai-speaking world from the mid-Ayutthaya period until the 20th century. As J. Layden observed, in On the Languages and Literature of the Indo-Chinese Nations (1808):[1]: 139–149

The Siamese or Thai language contains a great variety of compositions of every species. Their poems and songs are very numerous, as are their Cheritras, or historical and mythological fables. Many of the Siamese princes have been celebrated for their poetical powers, and several of their historical and moral compositions are still preserved. In all their compositions they either affect a plain, simple narrative, or an unconnected and abrupt style of short, pithy sentences, of much meaning. Their books of medicine are reckoned of considerable antiquity. Both in science and poetry those who affect learning and elegance of composition sprinkle their style copiously with Bali. ... The Cheritras or romantic fictions of the Siamese, are very numerous, and the personages introduced, with the exception of Rama and the characters of the Ramayana, have seldom much similarity to those of the Brahmans.[1]: 143–144

Ramakien

Most countries in Southeast Asia share an Indianised culture.[7][8][9] Thai literature was heavily influenced by the Indian culture and Buddhist-Hindu ideology since the time it first appeared in the 13th century. Thailand's national epic is a version of the Ramayana called the Ramakien, received from the Khmer through the Lavo Kingdom. The importance of the Ramayana epic in Thailand is due to the Thai's adoption of the Hindu religio-political ideology of kingship, as embodied by the Lord Rama. The former Siamese capital, Ayutthaya, was named after the holy city of Ayodhya, the city of Lord Rama. All Thai kings have been referred to as "Rama" to the present day.

The mythical tales and epic cycle of Ramakien provide the Siamese with a rich and perennial source for dramatic materials. The royal court of Ayutthaya developed classical dramatic forms of expression called khon and lakhon. Ramakien played a great role in shaping these dramatic arts. During the Ayutthaya period, khon, or a dramatized version of Ramakien, was classified as lakhon nai or a theatrical performance reserved for aristocratic audiences. A French diplomat, Simon de La Loubère, witnessed and documented it in 1687, during a formal diplomatic mission sent by King Louis XIV.[10] The Siamese drama and classical dance later spread throughout mainland Southeast Asia and influenced the art in neighboring countries, including Burma's own version of Ramayana, Cambodia, and Laos.[2]: 177

A number of versions of the Ramakien epic were lost in the destruction of Ayutthaya in 1767. Three versions currently exist. One of these was prepared under the supervision (and partly written by) King Rama I. His son, Rama II, rewrote some parts for khon drama. The main differences from the original are an extended role for the monkey god Hanuman and the addition of a happy ending. Many of popular poems among the Thai nobles are also based on Indian stories. One of the most famous is Anirut Kham Chan which is based on an ancient Indian story of Prince Anirudha.

Literature of the Sukhothai period

.jpg.webp)

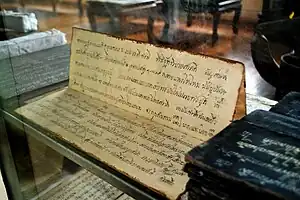

The Thai alphabet emerged as an independent writing system around 1283. One of the first work composed in it was the inscription of King Ram Khamhaeng (Thai: ศิลาจารึกพ่อขุนรามคำแหง) or Ram Khamhaeng stele, composed in 1292,[11] which serves both as the King's biography and as the Kingdom's chronicle.

The influence of Theravada Buddhism is shown in most pre-modern Thai literary works. Traibhumikatha or Trai Phum Phra Ruang (Thai: ไตรภูมิพระร่วง, "The Three Worlds according to King Ruang"), one of the earliest Thai cosmological treatise, was composed around the mid-14th century.[12] It is acknowledged to be one of the oldest traditional works of Thai literature. The Trai Phum Phra Ruang explains the composition of the universe, which, according to the Theravada Buddhist Thai, consists of three different "worlds" or levels of existence and their respective mythological inhabitants and creatures. The year of composition was dated at 1345 CE, whereas the authorship is traditionally attributed to the then designated heir to the throne and later King LiThai (Thai: พญาลิไทย) of Sukhothai. Traibhumikatha is a work of high scholarly standard. In composing it, King Lithai had to consult over 30 Buddhist treatises, including Tripitaka (Thai: พระไตรปิฎก) and Milinda Panha. It is acclaimed to be the first research dissertation in Thai literary history.

Literature of the Ayutthaya period

One of the representative works of the early Ayutthaya period is Lilit Ongkan Chaeng Nam (Thai: ลิลิตโองการแช่งน้ำ), an incantation in verse to be uttered before the gathering of courtiers, princes of foreign land, and representatives of vassal states at the taking of the oath of allegiance ceremony. It was a ritual to promote loyalty and close domestic and foreign alliances.

Lilit poetry

A lilit (Thai: ลิลิต) is a literary format which interleaves poetic verses of different metrical nature to create a variety of pace and cadence in the music of the poetry. The first Lilit poem to appear is Lilit Yuan Phai (Thai: ลิลิตยวนพ่าย 'the defeat of the Yuan', composed during the early-Ayutthaya period (c. 1475 CE). Yuan Phai is the Thai equivalent of the Song of Roland. It is an epic war poem of about 1180 lines, narrating the key events of the war between King Borommatrailokkanat (1448–1488) and King Tilokaraj of Lan Na, and providing a victory ode for the King of Siam. The importance of Yuan Phai is not limited to just being the oldest surviving example of Lilit poetry. It serves also as an important historical account of the war between Siam and Lan Na, as well as an evidence of the Siamese's theory of kingship that was evolving during the reign of Borommatrailokkanat.

Another famous piece of lilit poetry is Lilit Phra Lo (Thai: ลิลิตพระลอ) (c. 1500), a tragico-romantic epic poem that employed a variety of poetical forms. Phra Lo is roughly 2,600 lines in length. It is one of the major lilit compositions still surviving today and is considered to be the best among them. Phra Lo is considered to be one of the earliest Thai poems that evoke sadness and tragic emotions. The story ends with the tragic death of the eponymic hero and two beautiful princesses with whom he was in love. The erotic theme of the poem also made Phra Lo controversial among the Siamese noble classes for generations. While its author is unknown, Phra Lo is believed to have been written around the beginning of King Ramathibodi II's reign (1491-1529), and certainly not later than 1656, since a part of it was recited in a Thai textbook composed in the King Narai's reign. The plot probably came from a folk tale in the north of Thailand. Its tragic story has universal appeal and its composition is considered to be a high achievement under the Thai poetic tradition.

Maha-chat Kham Luang: the "Great Birth" sermon

The third major work of this period is Mahajati Kham Luang or Mahachat Kham Luang (Thai: มหาชาติคำหลวง), the Thai epic account of the "Great Birth" (maha-jati) of Vessantara Bodhisatta, the last final life before he became the Buddha. Mahachat was written in the style of the Buddhist chant (ร่าย) combining Pali verses with Thai poetical narrative. In 1492, King Borommatrailokkanat authorized a group of scholars to write a poem based on the story of Vessantara Jataka, believed to be the greatest of Buddha's incarnations. Their joint effort was this great work and the precedence of reciting Maha, the Great Life, was then established. Mahachat has traditionally been divided into 13 books. Six of them were lost during the sack of Ayutthaya and were ordered to be recomposed in 1815. There are many versions of Mahachat in Thailand today.

Royal panegyrics

The royal panegyric is a prominent genre in Thai poetry, possibly influenced by the Praśasti genre in Sanskrit. Passages in praise of kings appear in inscriptions from the Sukhothai kingdom. Praise of the king is a large element in Yuan Phai, a 15th-century war poem. The first work framed and titled specifically as a royal panegyric was the Eulogy of King Prasat Thong about King Narai’s father and predecessor, probably composed early in King Narai’s reign. The "Eulogy of King Narai", composed around 1680, includes a description of the Lopburi palace and an account of an elephant hunt.

Nirat: The Siamese tradition of parting and longing poetry

The nirat (Thai: นิราศ) is a lyrical genre, popular in Thai literature, which can be translated as 'farewell poetry'. The core of the poetry is a travel description, but essential is the longing for the absent lover. The poet describes his journey through landscapes, towns, and villages, but he regularly interrupts his description to express his feelings for and thoughts of the abandoned lover. Nirat poetry probably originated from the Northern Thai people. Nirat Hariphunchai (1637) is traditionally believed to be the first Nirat to appear in the Thai language. However, the Thai nirat tradition could prove to be much older, depending on whether Khlong Thawathotsamat could be dated back to the reign of King Borommatrailokkanat (1431-1488). Siamese poets composed Nirat with different poetical device. During the Ayutthaya period, poets liked to compose Nirat poems using khlong (โคลง) and kap (กาพย์) metrical variety. Prince Thammathibet (1715-1755) (Thai: เจ้าฟ้าธรรมธิเบศ) was a renowned Nirat poet whose works are still extant today.

Other representatives of this genus are Si Prat (1653-1688) (Thai: ศรีปราชญ์) and Sunthorn Phu (1786-1855) (Thai: สุนทรภู่). Since nirat poems record what the poet sees or experiences during his journey, they represent an information source for the Siamese culture as well as history in the premodern time. This poetical genre later spread, first to Myanmar in the late 18th Century, and then Cambodia in the mid 19th century, at the time when Cambodia was heavily influenced by the Siamese culture.[13] Famous poems in the nirat genre during the Ayutthaya period are:

- Khlong Thawathotsamāt (c. 1450?) (Thai: โคลงทวาทศมาส; "the Twelve-Month Song"): Thawathotsamat is a 1,037-line nirat poem in khlong meter. It is believed to be composed by a group of royal poets rather than by one man. It is formerly thought to be composed during the reign of King Narai, but in fact the language of this poem suggests a much older period. The large number of Sanskrit words in Thawathotsamat suggests that it was composed perhaps in the reign of King Borommatrailokkanat (1431-1488) when such literary style was common. Thawathotsamat is also an important work of Thai literature because it records the knowledge about specific traditions and norms practiced by Thai people in each month of a year. Thawathotsamat is also unique among the nirat genre of poetry because the poet(s) do not travel anywhere but they nonetheless express the longing and sadness that each month of separation from their loved ones brings.

- Khlong Nirat Hariphunchai (Thai: โคลงนิราศหริภุญชัย; account of a journey from Chiang Mai to Wat Phra That Hariphunchai in Lamphun, possibly dated to 1517/8. The royal author laments over his separation from a beloved named Si Thip.

- Khlong Kamsuan Sīprāt (Thai: โคลงกำสรวลศรีปราชญ์; "the mournful song of Sīprāt") by Sīprāt: A nirat poem composed in khlong dàn (Thai: โคลงดั้น) meter.

- Kap Hor Khlong Nirat Thansōk (Thai: กาพย์ห่อโคลงนิราศธารโศก; "a nirat at Thansōk stream in kap-hor-khlong verse") (c. 1745) by Prince Thammathibet: a nirat poem composed in a special style of kap hor khlong - where each of the khlong poems is enclosed in kap verses. This is a rare example of a highly polished and stately style of Thai poetry. Nirat Thansōk is 152-stanza long (1,022 lines).

- Kap Hor Khlong Praphat Than-Thongdang (Thai: กาพย์ห่อโคลงประพาสธารทองแดง; "a royal visit at Than-Thongdang stream in kap-hor-khlong verse") (c. 1745) by Prince Thammathibet. Another rare example of kap hor khlong genre. Only 108 stanzas of this poem have been found. The other half seems to have been lost.

The Siamese epic Khun Chang Khun Phaen

In the Ayutthaya period, folktales also flourished. One of the most famous folktales is the story of Khun Chang Khun Phaen (Thai: ขุนช้างขุนแผน), referred to in Thailand simply as "Khun Phaen", which combines the elements of romantic comedy and heroic adventures, ending in the tragic death of one of the main protagonists. The epic of Khun Chang Khun Phaen (KCKP) revolves around Khun Phaen, a Siamese general with super-human magical power who served the King of Ayutthaya, and his love-triangle relationship between himself, Khun Chang, and a beautiful Siamese girl named Wan-Thong. The composition of KCKP, much like other orally-transmitted epics, evolved over time. It originated as a recreational recitation or sepha within the Thai oral tradition from around the beginning of the 17th century (c.1600). Siamese troubadours and minstrels added more subplots and embellished scenes to the original storyline as time went on.[14] By the late period of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, it had attained the current shape as a long work of epic poem with the length of about 20,000 lines, spanning 43 samut thai books. The version that exists today was composed with klon meter throughout and is referred to in Thailand as nithan Kham Klon (Thai: นิทานคำกลอน) meaning a poetic tale. A standard edition of KCKP, as published by the National Library, is 1085-page long.

As the national epic of the Siamese people, Khun Chang Khun Phaen is unique among other major epic poems of the world in that it concerns the struggles, romance, and martial exploits of non-aristocratic protagonists - with a high degree of realism - rather than being chiefly about the affairs of great kings, noble men or deities.[14]: 1 The realism of KCKP also makes it standout from other epic literatures of the region. As Baker and Phongpaichit note, the depiction of war between Ayutthaya and Chiangmai in Khun Chang Khun Phaen is "[p]ossibly ... the most realistic depiction of pre-modern warfare in the region, portraying the adventure, the risk, the horror, and the gain."[14]: 14 KCKP additionally contains rich and detailed accounts of the traditional Thai society during the late Ayutthaya period, including religious practices, superstitious beliefs, social relations, household management, military tactics, court and legal procedures etc. To this day, KCKP is regarded as the masterpiece of Thai literature for its high entertainment value - with engaging plots even by modern standard - and its wealth of cultural knowledge. Marveling at the sumptuous milieu of old Siamese customs, beliefs, and practices in which the story takes place, William J. Gedney, a philologist specialized in Southeast Asian languages, commented that: “The quality of much of this work is superb, often entrancing for its elegance, grace, and vitality. One cannot help feeling that this body of traditional Thai poetry is among the finest artistic creations in the history of mankind.”[15] A complete English prose translation of KCKP was published by Chris Baker and P. Phongpaichit in 2010.[16]

The folk legend of Sri Thanonchai

Another popular character among Ayutthaya folktales is the trickster, the best known is Sri Thanonchai (Thai: ศรีธนญชัย), usually a heroic figure who teaches or learns moral lessons and is known for his charm, wit, and verbal dexterity.[17] Sri Thanonchai is a classic trickster-hero. Like Shakespeare's villains, such as Iago, Sri Thanonchai's motive is unclear. He simply uses his trickeries, jests and pranks to upend lives and affairs of others which sometimes results in tragic outcomes. The story of Sri Thanonchai is well known among both Thai and Lao people. In the Lao tradition, Sri Thanonchai is called Xiang Mieng. A Lao-Isaan version of Xiang Mieng describes Sri Thanonchai as an Ayutthayan trickster.[18]

The Legend of Phra Malai (1737)

The Legend of Phra Malai (Thai: พระมาลัยคำหลวง) is a religious epic adventure composed by Prince Thammathibet, one of the greatest Ayutthayan poets, in 1737, although the story's origin is assumed to be much older, being based on a Pali text. Phra Malai figures prominently in Thai art, religious treatises, and rituals associated with the afterlife, and the story is one of the most popular subjects of 19th-century illustrated Thai manuscripts.

Prince Thammathibet's Phra Malai is composed in a style that alternates between rai and khlong sii-suphap. It tells a story of Phra Malai, a Buddhist monk of the Theravada tradition said to have attained supernatural powers through his accumulated merit and meditation. Phra Malai makes a journey into the realm of hell (naraka) to teach Buddhism to the underworld creatures and the deceased.[19] Phra Malai then returns to the world of the living and tells people the story of the underworld, reminding listeners to make good merits and to adhere to the buddhist's teachings in order to avoid damnation. While in the human realm, Phra Malai receives an offering of eight lotus flowers from a poor woodcutter, which he eventually offers at the Chulamani Chedi, a heavenly stupa believed to contain a relic of the Buddha. In Tavatimsa heaven, Phra Malai converses with the god Indra and the Buddha-to-come, Metteyya, who reveals to the monk insights about the future of mankind. Through recitations of Phra Malai the karmic effects of human actions were taught to the faithful at funerals and other merit-making occasions. Following Buddhist precepts, obtaining merit, and attending performances of the Vessantara Jataka all counted as virtues that increased the chances of a favourable rebirth, or Nirvana in the end.

Other notable works from the Ayutthaya period

Three most famous poets of the Ayutthaya period were Sīprāt (1653-1688) (Thai: ศรีปราชญ์), Phra Maha Raja-Kru (Thai: พระมหาราชครู), and Prince Thammathibet (1715-1755) (Thai: เจ้าฟ้าธรรมธิเบศไชยเชษฐ์สุริยวงศ์). Sriprat composed Anirut Kham Chan ("the tale of Prince Anirudha in kham chan poetry") which is considered to be one of the best kham chan composition in the Thai language. Prince Thammathibet composed many extant refined poems, including romantic "parting and longing" poems. He also composed Royal Barge Procession songs or kap hé reu (Thai: กาพย์เห่เรือ) to be used during the King's grand seasonal water-way procession which is a unique tradition of the Siamese. His barge-procession songs are still considered best in the Thai repertoire of royal procession poems. Other notable literary works of the mid and late Ayutthaya Kingdom include:

- Sue-ko Kham Chan (Thai: เสือโคคำฉันท์) (c. 1657) by Phra Maha Raja-Kru (Thai: พระมหาราชครู). Sue-ko Kham Chan is the earliest-known surviving kham chan (Thai: คำฉันท์) poem to appear in the Thai language. It is based on a story from Paññāsa Jātaka (Thai: ปัญญาสชาดก) or Apocryphal Birth-Stories of the Buddha. Sue-ko Kham Chan narrates a story concerning a virtuous brotherly-like friendship between a calf and a tiger cub. Their love for each other impresses a rishi who asks the gods to turn them into humans on the merits of their virtues. Sue-ko Kham Chan teaches an important concept of Buddhist teaching according to which one becomes a human being, the highest species of the animal, not because he was born such, but because of his virtue or sila-dhamma (Thai: ศีลธรรม).

- Samutta-Kōt Kham Chan (Thai: สมุทรโฆษคำฉันท์) (c. 1657) by Phra Maha Raja-Kru. Samutta-Kōt kham chan is a religious-themed epic poem based on a story of Pannasa-Jataka. The poem is 2,218-stanza long (around 8,800 lines). However, the original poet, Phra Maha Raja-Kru, only composed 1,252 stanzas and did not finish it. King Narai (1633-1688) further composed 205 stanza during his reign and Paramanuchit-Chinorot, a noble-born poet monk and the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand, finished it in 1849. Samut-Koat Kham Chan was praised by the Literature Society as one of the best kham chan poems in the Thai language.

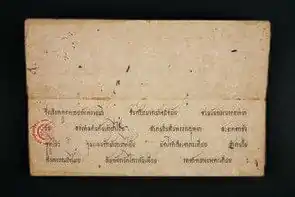

- Jindamanee (Thai: จินดามณี; "Gems of the Mind"): the first Thai grammar book and considered to be the most important book for teaching Thai language until the early 20th century. The first part was probably written during the reign of King Ekathotsarot (Thai: พระเจ้าเอกาทศรถ) (1605-1620).[20] The later part was composed by Phra Horathibodi, a royal scholar, in the reign of King Narai (1633-1688). Jindamanee instructs not only the grammar and the orthography of Thai language, but also the art of poetry. Jindamanee contains many valuable samples of Thai poems from works which are now lost. For a 400-year-old Asian grammar book, Jindamanee's didactic model is based on sound linguistic principles. Scholars believe that European knowledge on grammar, especially via French missionaries stationed in Siam during the 17th century, may have influenced its composition.

- Nang Sib Song (Thai: นางสิบสอง; "the twelve princesses") or Phra Rotthasen (Thai: พระรถเสน) or Phra Rot Meri (Thai: พระรถเมรี): an indigenous folk tale, based on a previous life of the Buddha, popularized in many Southeast Asian countries. There are several poetic retellings of this story in the Thai language. The story of Nang Sib Song concerns the life of twelve sisters abandoned by their parents and adopted by an Ogress Santhumala disguised as a beautiful lady. The conclusion is the sad love story about the only surviving son of the twelve sisters, Phra Rotthasen (พระรถเสน) with Meri (เมรี) the adopted daughter of ogress Santhumala. This is a story of unrequited love that ends with the death of the lovers, Rotthsen and Meri.

- Lakhon (Thai: ละคร): Lakhon is a highly regarded type dramatic performance and literature in Siam. It is divided into two categories: lakhon nai (Thai: ละครใน), dramatic plays reserved only for the aristocrats, and lakhon nōk (Thai: ละครนอก), plays for the enjoyment of the commoners. Only three plays have traditionally been classified as lakhon nai: Ramakien, Anirut, and Inao. Fifteen plays survived the destruction of Ayutthaya. Among the most well-known are:

- Sāng-thong (Thai: สังข์ทอง) - a play based on a Buddhist jataka story of a noble man who hides his identity by disguising as a black-skinned savage. Its popularity was revived during the early Rattanakosin era by King Rama II who rewrote many parts of it as lakorn nok.

- Inao (Thai: อิเหนา) - one of the three major lakhon nais. Inao was a very popular drama among the Siamese aristocrats of the late-Ayutthaya period. It is based on the East-Javanese Panji tales. Inao continued to be popular in the early-Rattanakosin era during which there are many adaptations of Inao in Thai language. The sack of Ayutthaya spread its popularity to Burma.

- Phikul Thong (Thai: พิกุลทอง) or Phóm Hóm (Thai: นางผมหอม):

Early Rattanakosin period

With the arrival of the Rattanakosin era, Thai literature experienced a rebirth of creative energy and reached its most prolific period. The Rattanakosin era is characterized by the imminent pressure to return to the literary perfection and to recover important literary works lost during the war between Ayutthaya and the Konbuang Empire. A considerable poetic and creative energy of this period was spent to revive or repair the national treasures which had been lost or damaged following the fall of the old Capital. Epics, notably Ramakien and Khun Chang Khun Phaen, were recomposed or collected - with aid of surviving poets and troubadours who had committed them to memory (not rare in the 18th century) - and written down for preservation. Nevertheless, many court singers and poets were carried away or killed by the invading Burmese army and some works were lost forever. But it goes to show how rich the Siamese literary creations, especially poetical works, must have been before the war, since so much still survived even after the destruction of their former Kingdom.

.jpg.webp)

The royal poets of the early Rattanakosin did not merely recompose the damaged or lost works of the Ayutthaya era but they also improved upon them. The Ramakien epic, recomposed and selected from various extant versions, during this period is widely considered to be more carefully worded than the old version lost to the fire. In addition, whereas the poet of Ayutthaya period did not care to adhere to strict metrical regulation of the indianised prosody, the compositions of Rattanakosin poets are so much more faithful to the metrical requirements. As a result, the poetry became generally more refined but also was rather difficult for the common man to appreciate. The literary circle of the early Rattanakosin era still only accepted poets who had a thorough classical education, with deep learning in classical languages. It was in this period that a new poetical hero, Sunthorn Phu (Thai: สุนทรภู่) (1786-1855) emerged to defy the traditional taste of the aristocrat. Sunthorn Phu consciously moved away from a difficult and stately language of court poetry and composed mostly in a popular poetical form called klon suphap (Thai: กลอนสุภาพ). He mastered and perfected the art of klon suphap and his verses in this genre are considered peerless in the Thai language to the present day. There were also other masterpieces of Klon-suphap poem from this era, such as "Kaki Klon Suphap" – which influences the Cambodian Kakey – by Chao Phraya Phrakhlang (Hon).

The literary recovery project also resulted in the improvement of prose composition - an area which had been neglected in the previous Kingdom. A translation committee was set up in 1785, during the reign of King Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok (Rama I), to translate important foreign works for the learning of the Thai people. This includes the Mon Chronicle Rachathirat as well as Chinese classics, such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms or Sam-kok (Thai: สามก๊ก), Investiture of the Gods or Fengshen (Thai: ห้องสิน), Water Margin or Sòngjiāng (Thai: ซ้องกั๋ง). These long prose works became a gold standard of Thai classical prose composition.

King Rama II: poet king of Thailand

King Phra Phutthaloetla Naphalai, also known as King Rama II of Siam (r. 1809-1824), was a gifted poet and playwright and is also a great patron of artists. His reign was known as the "golden age of Rattanakosin literature". His literary salon was responsible for reviving and repairing many important works of literature which were damaged or lost during the sack of Ayutthaya. Poets, including Sunthorn Phu, thrived under his patronage. King Loetlanaphalai was himself a poet and artist. He is generally ranked second only to Sunthorn Phu in terms of poetic brilliance. As a young prince, he took part in recomposing the missing or damaged parts of Thai literary masterpieces, including Ramakien and Khun Chang Khun Phaen. He later wrote and popularized many plays, based on folk stories or old plays that survived the destruction of the old capital, including:

- Inao (Thai: อิเหนา)

- Krai Thong (Thai: ไกรทอง): a Thai folktale, originating from Phichit Province. It tells the story of Chalawan (ชาลวัน), a crocodile lord who abducts a daughter of a wealthy Phichit man, and Kraithong, a merchant from Nonthaburi who seeks to rescue the girl and must challenge Chalawan. The story was adapted into a lakhon nok play, by King Rama II ,[21]

- Kawee (Thai: คาวี)

- Sang Thong (Thai: สังข์ทอง)

- Sang Sín Chai (Thai: สังข์ศิลป์ชัย)

- Chaiya Chet (Thai: ไชยเชษฐ์): a Thai folk story originating in the Ayutthaya period. Its popularity led to the dramatization of the story into lakhon. King Rama II rewrote the play for lakhon nok (ละครนอก), i.e., non-aristocratic theatre performances.

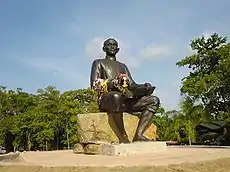

Sunthorn Phu's Phra Aphai Mani: the Siamese Odyssey

The most important Thai poet in this period was Sunthorn Phu (สุนทรภู่) (1786-1855), widely known as "the bard of Rattanakosin" (Thai: กวีเอกแห่งกรุงรัตนโกสินทร์). Sunthorn Phu is best known for his epic poem Phra Aphai Mani (Thai: พระอภัยมณี), which he started in 1822 (while in jail) and finished in 1844. Phra Aphai Mani is a versified fantasy-adventure novel, a genre of Siamese literature known as nithan kham klon (Thai: นิทานคำกลอน). It relates the adventures of the eponymous protagonist, Prince Aphai Mani, who is trained in the art of music such that the songs of his flute could tame and disarm men, beasts, and gods. At the beginning of the story, Phra Aphai and his brother are banished from their kingdom because the young prince chooses to study music rather than to be a warrior. While in exile, Phra Aphai is kidnapped by a female Titan (or an ogress) named Pii Sue Samut ('sea butterfly'; Thai: ผีเสื้อสมุทร) who falls in love with him after she hears his flute music. Longing to return home, Phra Aphai manages to escape the ogress with the help of a beautiful mermaid. He fathers two sons, one with the ogress and another with the mermaid, who later grow up to be heroes with superhuman powers. Phra Aphai slays Pii Sue Samut (the ogress) with the song of his flute and continues his voyage; he suffers more shipwrecks, is rescued, and then falls in love with a princess named Suwanmali. A duel breaks out between Phra Aphai and Prince Ussaren, Suwanmali's fiancé, with the maiden's hand as the prize. Phra Aphai slays his rival. Nang Laweng, Ussaren's sister and queen of Lanka (Ceylon), vows revenge. She bewitches rulers of other nations with her peerless beauty and persuades them to raise a great coalition army to avenge her fallen brother. Phra Aphai, too, is bewitched by Nang Laweng's beauty. Nevertheless, he confronts Nang Laweng and they fall in love. The war and various troubles continue, but Phra Aphai and his sons prevail in the end. He appoints his sons as rulers of the cities he has won. Now tired of love and war, Phra Aphai abdicates the throne and retires to the forest with two of his wives to become ascetics.

Composition and versions

The epic tale of Phra Aphai Mani is a massive work of poetry in klon suphap (Thai: กลอนสุภาพ). The unabridged version published by the National Library is 48,686-bāt (two line couplets) long, totaling over 600,000 words, and spanning 132 samut Thai books—by far the single longest poem in the Thai language,[22] and is the world's second longest epic poem written by a single poet. Sunthorn Phu, however, originally intended to end the story at the point where Phra Aphai abdicates the throne and withdraws. This leaves his original vision of the work at 25,098 bāt (two line couplet) of poetry, 64 samut thai books. But Sunthorn Phu's literary patron wanted him to continue composing, which he did for many years. Today, the abridged version, i.e., his original 64 samut-thai volumes, or 25,098 couplets of poetry—is regarded as the authoritative text of the epic.[22] It took Sunthorn Phu more than 20 years to compose (from c. 1822 or 1823 to 1844).

Phra Aphai Mani is Sunthorn Phu's chef-d'œuvre. It breaks the literary tradition of earlier Thai poetic novels or nithan kham-klon (Thai: นิทานคำกลอน) by including Western mythical creatures, such as mermaids, and contemporary inventions, such as steam-powered ships (Thai: สำเภายนต์) which only started to appear in Europe in the early-1800s. Sunthorn Phu also writes about a mechanical music player at the time when a gramophone or a self-playing piano was yet to be invented. This made Phra Aphai Mani surprisingly futuristic for the time. Also, unlike other classical Thai epic poems, Phra Aphai Mani depicts various exploits of white mercenaries and pirates which reflects the ongoing European colonization of Southeast Asia in the early-19th century. Phra Aphai himself is said to have learned "to speak farang (European), Chinese, and Cham languages." Moreover, the locations of cities and islands in Phra Aphai Mani are not imagined but actually correspond to real geographical locations in the Andaman Sea as well as east of the Indian Ocean. Sunthorn Phu could also give an accurate description of modern sea voyage in that part of the world. This suggests that the Sunthorn Phu must have acquired this knowledge from foreign seafarers first-hand. The multi-cultural and the half-mythical, half-realistic setting of Phra Aphai Mani combined with Sunthorn Phu's poetic power, makes Phra Aphai Mani a masterpiece.

Sunthorn Phu as the poet of two worlds

European colonial powers had been expanding their influence and presence into Southeast Asia when Sunthorn Phu was composing Phra Aphai Mani. Many Thai literary critics have thus suggested that Sunthorn Phu may have intended his epic masterpiece to be an anti-colonialist tale, disguised as a versified tale of fantasy adventures.[23] In a literary sense, however, Phra Aphai Mani has been suggested by other Thai academics as being inspired by Greek epics and Persian literature, notably the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Argonauts, and Thousand and One Nights.

The structure of Phra Aphai Mani conforms to the monomyth structure, shared by other great epic stories in the Greek and Persian tradition. It is possible that Sunthorn Phu may have learned these epic stories from European missionaries, Catholic priests, or learned individuals who travelled to Siam during the early-19th century. Phra Aphai, the protagonist, resembles Orpheus—the famed musician of the Argonauts—rather than an Achilles-like warrior. Moreover, Phra Aphai's odyssean journey conjures similarity with the King of Ithaca's famous journey across the Aegean.

Pii Sue Samut ("the sea butterfly"), a love-struck female titan who kidnaps the hero, is reminiscent of the nymph Calypso. Also, much like Odysseus, Phra Aphai's long voyage enables him to speak many languages and to discern the minds and customs of many foreign races. Phra Aphai's name (Thai: อภัย: 'to forgive') is pronounced quite similar to how "Orpheus" (Greek: Ὀρφεύς) is pronounced in Greek. In addition, Nang Laweng's bewitching beauty, so captivating it drives nations to war, seems to match the reputation of Helen of Troy. Others have suggested that Nang Laweng may have been inspired by a story of a Christian princess, as recounted in Persia's Thousand and One Nights, who falls in love with a Muslim king.[23]

All of this suggests that Sunthorn Phu was a Siamese bard with a bright and curious mind who absorbed, not only the knowledge of contemporary seafaring and Western inventions, but also stories of Greek classical epics from learned Europeans. In composing Phra Aphai Mani, Sunthorn Phu demonstrates a grand poetic ambition. He became the first Thai writer to draw inspirations from Western literary sources and produces an epic based, loosely, upon an amalgamation of those myths and legends. Thus, rather than writing with a political motive, Sunthorn Phu might simply have wanted to equal his literary prowess to the most famed poets and writers of the West.

Sunthorn Phu's other literary legacy

Sunthorn Phu is also the master of the Siamese tradition of parting-and-longing poetry or nirat which was popular among Thai poets who journeyed away from loved ones. Sunthorn Phu composed many nirat poems, probably from 1807 when he was on a trip to Mueang Klaeng (เมืองแกลง), a town between Rayong (his hometown) and Chanthaburi. There are many forms of "travel" or parting-and-longing poetry in the Thai language. In the Ayutthaya period, these were composed by noblemen (such as Prince Thammathibet (1715-1756)), whose sentimentality and expressions were refined and formal. Sunthorn Phu was different because he was a common man and his poetry is more fun (สนุก), catchy, and humorous. Sunthorn Phu was probably not as classically trained as other Thai famous poets (who were often members of the royal family) in the past. Nidhi Eoseewong, a Thai historian, argues that Sunthorn Phu's success can be attributable to the rise of the bourgeoisie or the middle class audience—following the transformation of Siam from a feudal society to a market economy—who held different values and had different tastes from aristocrats.[24]

Sunthorn Phu was therefore, like Shakespeare, a people's poet. Instead of exclusively writing to please aristocratic institutions or patrons, Sunthorn Phu also writes both to entertain and to instruct, which shows his confidence in his personal mission as a poet. His works were thus popular among common Siamese, and he was prolific enough to make a living from it. Sunthorn Phu exercised his "copyright" by allowing people to make copies of his nithan poems (Thai: นิทานคำกลอน), such as Phra Aphai Mani, for a fee.[25] This made Sunthorn Phu one of the first Thais to ever earn a living as an author. Although a bard of the royal court, he was disdained by many genteel and noble-born poets for appealing to the common people.

Sunthorn Phu was a prolific poet. Many of Sunthorn Phu's works were lost or destroyed due to his sojourn lifestyle. However, much is still extant. He is known to have composed:

Modern Thai literature

Kings Rama V and Rama VI were also writers, mainly of non-fiction works as part of their programme to combine Western knowledge with traditional Thai culture. The story Lilit Phra Lo (ลิลิตพระลอ) was voted the best lilit work by King Rama VI's royal literary club in 1916. Based on the tragic end of King Phra Lo, who died together with the two women he loved, Phra Phuean and Phra Phaeng, the daughters of the ruler of the city of Song, it originated in a tale of Thai folklore and later became part of Thai literature.[26]

Twentieth century Thai writers tended to produce light fiction rather than literature. But increasingly, individual writers are being recognized for producing more serious works, including writers like Kukrit Pramoj, Kulap Saipradit, (penname Siburapha), Suweeriya Sirisingh (penname Botan), Chart Korbjitti, Prabda Yoon, Duanwad Pimwana,[27] and Pitchaya Sudbanthad.[28] Some of their works have been translated into English. The Isan region of Thailand has produced two literary social critics in Khamsing Srinawk and Pira Sudham. Notably, Pira Sudham writes in English.

Thailand had a number of expatriate writers in the 20th century as well. The Bangkok Writers Group publishes fiction by Indian author G. Y. Gopinath, the fabulist A. D. Thompson, as well as non-fiction by Gary Dale Cearley.

Thai literary influence on neighbouring countries

Thai literature, especially its poetic tradition, has had a strong influence on neighbouring countries, especially Burma and Cambodia. The two golden periods of Burmese literature were the direct consequences of the Thai literary influence. The first occurred during the two-decade period (1564–1583) when the Toungoo Dynasty made Siam a vassal state. The conquest incorporated many Thai elements into Burmese literature. Most evident were the yadu or yatu (ရာတု), an emotional and philosophic verse, and the yagan (ရာကန်) genre. The next transmission of Thai literary influence to Burma happened in the aftermath of the fall of Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1767. After a second conquest of Ayutthaya (Thailand), many Siamese royal dancers and poets were brought back to the court of Konbaung. Ramakien, the Thai version of Ramayana (ရာမယန) was introduced and was adapted in Burmese where it is now called Yama Zatdaw. Many dramatic songs and poems were transliterated directly from the Thai language. In addition, the Burmese also adopted the Thai tradition of Nirat poetry, which became popular among the Burmese royal class. Burmese literature during this period was therefore modeled after the Ramayana, and dramatic plays were patronised by the Burmese court.[29]

Cambodia had fallen under Siamese hegemony in the reign of King Naresuan. But it was during the Thonburi Kingdom that the high cultures of the Rattanakosin kingdom were systematically transmitted to a Cambodian court that absorbed them voraciously. As Fédéric Maurel, a French historian, notes:

From the close of the eighteenth century and through the nineteenth century, a number of Khmer pages, classical women dancers, and musicians studied with Thai ajarn (masters or teachers) in Cambodia. The presence of this Thai elite in Cambodia contributed to the development of strong Thai cultural influence among the Khmer upper classes. Moreover, some members of the Khmer royal family went to the Thai court and developed close relations with well-educated Thai nobility, as well as several court poets. Such cultural links were so powerful that, in some fields, one might use the term Siamization in referring to the processes of cultural absorption at the Khmer court at that time.[30]

It was during this period of Siamzation that Thai literary influence had a wholesale impact on Khmer literature. The Nirat or Siamese tradition of parting poetry was emulated by Khmer poets; and many Thai stories were translated directly from the Siamese source into Khmer language.[30]

One Thai study on comparative literature found that Cambodia's current version of Ramayana (Reamker) was translated directly from the Thai source, stanza by stanza.[31] The Cambodian royal court used to stage Thai lakhon dramas in Thai language during King Narodom's reign.[31]: 54 While older Reamker literary texts may have existed before the 16th century but most of the work has now been lost.[32][33]

See also

- Ka Kee

- Phra Saraprasoet

- Phya Anuman Rajadhon

- Sangsilchai

- Thai folklore

References

- Layden, J. (1808). "On the Languages and Literature of the Indo-Chinese Nations". Miscellaneous Papers Relating to Indo-China Vol.1. London: Trübner & Co. 1886. pp. 84–171.

- Low, James (1836). On Siamese Literature (PDF). pp. 162–174.

- Haarman, Harald (1986). Language in Ethnicity; A View of Basic Ecological Relations. p. 165.

In Thailand, for instance, where the Chinese influence was strong until the Middle Ages, Chinese characters were abandoned in the writing of the Thai language in the course of the thirteenth century.

- Leppert, Paul A. (1992). Doing Business With Thailand. p. 13.

At an early time the Thais used Chinese characters. But, under the Indian traders and monks, they soon dropped Chinese characters in favor of Sanskrit and Pali scripts.

- Chamberlain, James (1989). "Thao Hung or Cheuang: A Tai Epic Poem" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies (18–19): 14–34.

- Terwiel, B.J. (1996). "The Introduction of Indian Prosody Among the Thai". In Jan E.M. Houben (ed.). Ideology and Status of Sanskrit-Contribution to the History of Sanskrit Language. E.J.Brill. pp. 307–326. ISBN 9-0041-0613-8.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2002), "From Funan to Sriwijaya: Cultural continuities and discontinuities in the Early Historical maritime states of Southeast Asia", 25 tahun kerjasama Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi dan Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi / EFEO, pp. 59–82

- Lavy, Paul (2003), "As in Heaven, So on Earth: The Politics of Visnu Siva and Harihara Images in Preangkorian Khmer Civilisation", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 34 (1): 21–39, doi:10.1017/S002246340300002X, S2CID 154819912, retrieved 23 December 2015

- Kulke, Hermann (2004). A history of India. Rothermund, Dietmar 1933- (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0203391268. OCLC 57054139.

- La Loubère, Simon (1693). A new historical relation of the kingdom of Siam. London: Printed by F.L. for Tho. Horne, Francis Saunders, and Tho. Bennet. p. 49.

- Cœdès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans. Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Lithai (1345). Traibhumikatha: The Story of Three Planes of Existence. ASEAN (1987). ISBN 9748356310.

- Maurel, Frédéric (2002). "A Khmer "nirat", 'Travel in France during the Paris World Exhibition of 1900': influences from the Thai?". South East Asia Research. 10 (1): 99–112. doi:10.5367/000000002101297026. JSTOR 23749987. S2CID 146881782.

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2009). "The Career of Khun Chang Khun Phaen" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 97: 1–42.

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2010). The Tale of Khun Chang Khun Phaen. Silkworm Books. p. x. ISBN 978-9-7495-1195-4.

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2010). The Tale of Khun Chang Khun Phaen. Silkworm Books. p. 960. ISBN 978-9-7495-1195-4.

- Arne Kislenko (2004) Culture and Customs of Thailand. Greenwood. ISBN 9780313321283, p. 46

- "Sepha Sri Thanonchai Xiang Mieng". Vajirayana.org.

- "A Thai book of merit: Phra Malai's journeys to heaven and hell". Asian and African studies blog.

- "Jindamanee". Thairat (in Thai). 23 January 2017.

- Permkesorn, Nuanthip. "ไกรทอง" [Krai Thong]. Thai Literature Directory. Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- "พระอภัยมณี, คำนำเมื่อพิมพ์ครั้งแรก". หอสมุดวชิรญาณ. 2016-06-23.

- "พระอภัยมณีวรรณคดีการเมือง ต่อต้านการล่าเมืองขึ้น" (PDF). สุจิตต์ วงษ์เทศ.

- วงษ์เทศ, สุจิตต์ (2006). รำพันพิลาปของสุนทรภู่. มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร. pp. 67–71.

- Damrong Rajanubhab (1975), Life and Works of Sunthorn Phu (Thai)

- Thai Literature

- Scrima, Andrea (April 2019). "Duanwad Pimwana and Mui Poopoksakul with Andrea Scrima". The Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|ref= - Aw, Tash (9 March 2019). "Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad review – a city of memories". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "Ramayana in Myanmar's Heart". Archived from the original on 29 October 2006. Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- Maurel 2002, p. 100.

- Pakdeekham, Santi (2009). "Relationships between early Thai and Khmer plays". Damrong Journal. 8 (1): 56.

- Marrison, G. E. (1989). "Reamker (Rāmakerti), the Cambodian Version of the Rāmāyaṇa. A Review Article". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 121 (1): 122–129. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00167917. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25212421. S2CID 161831703.

- Marrison, G. E. (January 1989). "Reamker (Rāmakerti), the Cambodian versions of the Rāmāyaṇa.* a review article". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 121 (1): 122–129. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00167917. ISSN 2051-2066. S2CID 161831703.