London Ringways

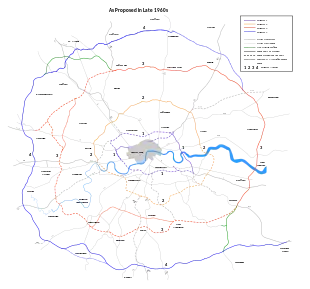

The London Ringways were a series of four ring roads planned in the 1960s to circle London at various distances from the city centre. They were part of a comprehensive scheme developed by the Greater London Council (GLC) to alleviate traffic congestion on the city's road system by providing high speed motorway-standard roads within the capital, linking a series of radial roads taking traffic into and out of the city.

There had been plans to construct new roads around London to help traffic since at least the 17th century. Several were built in the early 20th century such as the North Circular Road, Western Avenue and Eastern Avenue, and further plans were put forward in 1937 with The Highway Development Survey, followed by the County of London Plan in 1943. The Ringways originated from these earlier plans, and consisted of the main four ring roads and other developments. Certain sections were upgrades of existing earlier projects such as the North Circular, but much of it was new-build. Construction began on some sections in the 1960s in response to increasing concern about car ownership and traffic.

The Ringway plans attracted vociferous opposition towards the end of the decade over the demolition of properties and noise pollution the roads would cause. Local newspapers published the intended routes, which caused an outcry among local residents living on or near them who would have their lives irreversibly disrupted. Following an increasing series of protests, the scheme was cancelled in 1973, at which point only three sections had been built. Some traffic routes originally planned for the Ringways were re-used for other road schemes in the 1980s and 1990s, most significantly the M25, which was created out of two different sections of Ringways joined together. The project caused an increase in road protesting and an eventual agreement that new road construction in London was not generally possible without huge disruption. Since 2000, Transport for London has promoted public transport and discouraged road use.

History

Background

London has been significantly congested since the 17th century. Various select committees were established in the late 1830s and early 1840s in order to establish means of improving communication and transport in the city. The Royal Commission on London Traffic (1903–05) produced eight volumes of reports on roads, railways and tramways in the London area, including a suggestion for "constructing a circular road about 75 miles in length at a radius of 12 miles from St Paul's".[1]

Between 1913 and 1916, a series of conferences took place, bringing all road plans in Greater London together as a single body. Over the next decade, 214 miles (344 km) of new roads were constructed, primarily as post-war unemployment relief. These included the North Circular Road from Hanger Lane to Gants Hill, Western Avenue and Eastern Avenue, the Great West Road bypassing Brentford, and bypasses of Kingston, Croydon, Watford and Barnet.[2] In 1924, the Ministry of Transport proposed another circular route, the North Orbital Road. This ran further out from London than the North Circular and was planned to be around 70 miles (110 km) long, running from the A4 at Colnbrook to the A13 at Tilbury.[3]

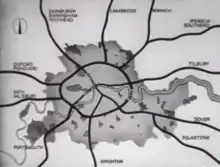

The Highway Development Survey, 1937

In May 1938, Sir Charles Bressey and Sir Edwin Lutyens published a Ministry of Transport report, The Highway Development Survey, 1937, which reviewed London's road needs and recommended the construction of many miles of new roads and the improvement of junctions at key congestion points.[4] Amongst their proposals was the provision of a series of orbital roads around the city with the outer ones built as American-style Parkways – wide, landscaped roads with limited access and grade-separated junctions.[4] These included an eastern extension of Western Avenue, which eventually became the Westway.[5]

Bressey's plans called for significant demolition of existing properties, that would have divided communities if they had been built. However, he reported that the average traffic speed on three of London's radial routes was 12.5 miles per hour (20.1 km/h), and consequently their construction was essential.[4] The plans stalled, as the London County Council were responsible for roads in the capital, and could not find adequate funding.[6]

County of London Plan and Greater London Plan, 1940s

The Ringway plan had developed from early schemes prior to the Second World War through Sir Patrick Abercrombie's County of London Plan, 1943 and Greater London Plan, 1944. One of the topics that Abercrombie's two plans had examined was London's traffic congestion, and The County of London Plan proposed a series of ring roads labelled A to E to help remove traffic from the central area.[7][8]

Even in a war-ravaged city with large areas requiring reconstruction, the building of the two innermost rings, A and B, would have involved considerable demolition and upheaval. The cost of the construction works needed to upgrade the existing London streets and roads to dual carriageway or motorway standards was considered significant; the A ring would have displaced 5,300 families.[9] Because of post-war funding shortages, Abercrombie's plans were not intended to be carried out immediately. They were intended to be gradually built over the next 30 years. The subsequent austerity period meant that very little of his plan was carried out. The A Ring was formally cancelled by Clement Attlee's Labour government in May 1950.[9] After 1951, the County of London focused on improving existing roads rather than Abercrombie's proposals.[10]

Ringway Scheme, 1960s

By the start of the 1960s, the number of private cars and commercial vehicles on the roads had increased considerably from the number before the war. British car manufacturing doubled between 1953 and 1960.[11] The Conservative government, led by Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, had strong ties to the road transport industry, with more than 70 members of parliament being members of the British Road Federation. Political pressure to build roads and improve vehicular traffic increased, which led to a revival of Abercrombie's plans.[12]

The Ringway plan took Abercrombie's earlier schemes as a starting point and reused many of his proposals in the outlying areas but scrapped the plans in the inner zone. Abercrombie's A Ring was scrapped as being far too expensive and impractical.[13] The innermost circuit, Ringway 1, was approximately the same distance from the centre as the B Ring. It used some of Abercrombie's suggested route, but it was planned to use existing transport corridors, such as railway lines, much more than before. The location of these lines produced a ring that was distinctly box-shaped and Ringway 1 was unofficially called the London Motorway Box.[14]

In 1963, Colin Buchanan published a report, Traffic in Towns, which had been commissioned by the Transport Minister, Ernest Marples. In contrast to earlier reports, it cautioned that road building would generate and increase traffic and cause environmental damage. It also recommended pedestrianisation of town centres and segregating different traffic types. The report was published by Penguin Books and sold 18,000 copies. Several key ideas in the report would later be perceived as being correct as road protesting grew from the 1980s onward.[15] The London Traffic Survey was published the following year, and concluded that the Ringways should be built in order to cater for future network traffic, instead of Traffic in Towns which said if a road was not built, there would be no demand along that route anyway.[16] The 1960s plans were developed over a period of several years and were subject to a continuing process of review and modification. Roads were added and omitted as the overall scheme was altered and many alternative route alignments were considered during the planning process.[17] The plan was published in stages starting with Ringway 1 in 1966 and Ringway 2 in 1967. After the Conservatives won the GLC elections in the latter year, they confirmed that both Ringways would be constructed as planned.[18]

The plan was hugely ambitious and almost immediately attracted opposition from several directions.[19] Ringway 1 was designed to be an eight-lane elevated motorway running through the middle of many town centres such as Camden Town, Brixton and Dalston.[20][21] A principal problem was the route of Ringway 2 in south London, since the South Circular Road was largely an unimproved series of urban streets and there were fewer railway lines to follow. Parts would be built with four lanes in each direction, and in some cases there was no other plan than to destroy whatever urban streets were in the way of the new road.[19] At Blackheath, the road would have run in a deep-bored tunnel to avoid any impact on the local area, at an estimated cost of £38 million.[22] However, until around 1967, the opposition was more towards specific proposals instead of the concept of Ringways generally.[23]

The report Motorways in London, published in 1969 by the architect/planner Lord Esher and Michael Thomson, a transport economist at the London School of Economics, calculated that costs had been enormously underestimated and would show marginal economic returns. They predicted large quantities of additional traffic that would be generated purely as a result of the new roads.[24] Access to the new roads would soon be overwhelmed even before the rings and radial roads were near capacity, while about 1 million Londoners would find their lives blighted by living within 200 yards of a motorway.[25] Reports suggested between 15,000 and 80,000 Londoners would lose their homes as a result of the Ringways.[26] The Treasury and the Ministry of Transport both came out against the scheme, primarily because of worries over the cost. The Chancellor of the Exchequer Roy Jenkins said he could not prevent the GLC from proposing the schemes, but assumed that the government could ultimately prevent them from being implemented.[27]

Despite this opposition, the GLC continued to develop its plans, and began the construction of some of the parts of the scheme. The plan, still with much of the detail to be worked out, was included in the Greater London Development Plan, 1969 (GLDP) along with much else not related to roads and traffic management. In 1970, the GLC estimated that the cost of building Ringway 1 along with sections of 2 and 3 would be £1.7 billion (approximately £28 billion as of 2021).[28][29]

In 1970, the British Road Federation surveyed 2,000 Londoners, 80% of whom favoured more new roads being built.[30] In contrast, a public enquiry was held to review the GLDP in a climate of strong and vocal opposition from many of the London Borough councils and residents associations that would have seen motorways driven through their neighbourhoods. The Westway and a section of the West Cross Route from Shepherd's Bush to North Kensington, opened in 1970. It showed the public what the Ringways would be like for local residents and what demolition would be required, and led to increased complaints over the scheme.[31] The GLDP received 22,000 formal objections by 1972.[32] The GLC realised that the South Cross Route might be impractical to build, and looked instead at integrating public transport through a new park-and-ride scheme at Lewisham that would serve a new Fleet line on the London Underground.[33]

The GLC attempted to hold on to the Ringway plans until the early 1970s, hoping that they would eventually be built.[34] By 1972, in an attempt to placate the Ringway plan's vociferous opponents, the GLC removed the northern section of Ringway 1 and the southern section of Ringway 2 from the proposals.[35] In January 1973, the enquiry recommended that Ringway 1 be built, but that much of the rest of the Ringway schemes be abandoned.[36] The project was submitted to the Conservative government for approval and, for a short period, it appeared that the GLC had made enough concessions for the scheme to proceed.[37] A report around this time commissioned by planning lawyer Frank Layfield showed that the GLDP was too dependent on roads for its transport plans.[38] Because the GLC had proposed the Ringways as a complete scheme, protesters against specific parts of it in different areas were able to unite against a common goal, which led to the Layfield Inquiry successfully challenging the proposals.[23]

The Labour party made large gains in the GLC elections of April 1973 with a policy of fighting the Ringways scheme. Given the continuing fierce opposition across London and the likely enormous cost, the cabinet cancelled funding and hence the project.[32][39]

Ringway 1

Ringway 1 was the London Motorway box, comprising the North, East, South and West Cross Routes.[40] Ringway 1 was planned to comprise four sections across the capital forming a roughly rectangular box of motorways. These sections were designated:[41]

- North Cross Route – from Harlesden to Hackney Wick via West Hampstead, Camden Town, Highbury and Dalston

- East Cross Route – from Hackney Wick to Kidbrooke via Bow, Blackwall and Greenwich

- South Cross Route – from Kidbrooke to Battersea via Lewisham, Peckham, Brixton and Clapham

- West Cross Route – from Battersea to Harlesden via Sands End, Earl's Court, West Kensington, Shepherd's Bush and North Kensington

Much of the scheme would have been constructed as elevated roads on concrete pylons and the routes were designed to follow the alignments of existing railway lines to minimise the amount of land required for construction, including the North London line in the north, the Greenwich Park branch line in the south, and the West London line to the west.[20][42]

Ringway 1 was expected to cost £480 million (£7.9 billion today) including £144 million (£2.3 billion today) for property purchases. It would require 1,048 acres (4.24 km2) and affect 7,585 houses.[43]

Only two parts of Ringway 1 were completed and opened to traffic. Part of the West Cross Route between North Kensington and Shepherd's Bush was opened by John Peyton and Michael Heseltine in 1970, simultaneously with Westway, to protests; some residents hung a huge banners with 'Get us out of this Hell – Rehouse Us Now' outside their windows and protesters disrupted the opening procession by driving a lorry the wrong way along the new road.[44][45] The East Cross Route, incorporating the new 'eastern bore' of the Blackwall Tunnel opened in 1967, was completed in 1979.[46]

The North Cross Route began south of Willesden Junction and followed the North London line eastwards then passed under the Midland main line and Metropolitan line at West Hampstead, where it was intended to meet a planned extension of the M1 motorway with a link to Finchley Road. It diverged away from the railway and passed through Hampstead in a cut-and-cover tunnel owing to local geography, and over British Rail's goods depot at Camden Town, where there was to be an interchange with the proposed Camden Town bypass. It again followed the North London line to the north of St Pancras and King's Cross, then ran in a tunnel through Highbury, and crossed Kingsland High Street in Dalston on a viaduct. It continued along the North London line through Hackney and Homerton, leading to a junction with the East Cross Route at Hackney Wick.[42]

The whole of the East Cross Route was built. It runs south from Hackney Wick as the A12 (previously designated as the A102(M) and A102) to Bow Road, then, as the A102, under the River Thames via the Blackwall Tunnel to the Sun in the Sands roundabout at Blackheath, then as the A2 to Kidbrooke, meeting the South Cross Route.[47]

The South Cross Route ran beneath Blackheath Park in a tunnel, following railways as much as possible for its route though Peckham, Brixton, where it was planned to connect with the "South Cross Route to Parkway D Radial" a motorway running south-east to Ringway 3, and Clapham to Nine Elms. There was then a link to the West Cross Route and Ringway 2 at Wandsworth.[48]

The West Cross Route followed the West London line, with a bridge over the Thames near Chelsea Basin. There was a planned interchange with Cromwell Road (A4) at Earl's Court and with Holland Park Avenue at Shepherd's Bush. The section north Shepherd's Bush to the Westway was constructed as planned. North of the Westway, it would have continued to follow the West London line, crossing the Great Western railway and the Grand Union Canal, linking with the North Cross Route at Willesden Junction.[48]

Ringway 2

Ringway 2 was an upgrade of North Circular Road (A406) and a new motorway to replace South Circular Road (A205).[49] The North Circular Road was largely a coherent route (see "Background" above), but the South Circular Road was merely a signposted route through the suburbs of South London on pre-existing sections of standard roads, involving twists and turns, selected by route planners in the 1930s. South of the River, Ringway 2 would have headed roughly in a direction towards North Circular Road at Chiswick, though there was no definite proposed route.[50] Much of the Ringway, particularly the southern section where a new route was required, would have been placed in cuttings to mitigate disruption to local residents.[51][52]

Northern section

The North Circular Road was to have been improved to motorway standard along its existing route. Some plans refer to the section in east London as the M15, but this was not planned to refer to the entire road. Since the Ringways Plan was cancelled, most of the route has been upgraded, some of it close to motorway standard, but this has been done piecemeal. In places, the road is a six-lane dual carriageway with grade separated junctions, while other parts remain at a much lower standard. In some cases this has been because of protests; the junction of North Circular Road and the A10 was only completed in 1990 after several other schemes had been blocked.[53]

At the western end of North Circular Road a new section of motorway would have been constructed to take the route of Ringway 2 eastwards from the junction with the M4 at Gunnersbury along the course of the railway line through Chiswick to meet and cross the River Thames at Barnes. This section was never well planned and did not have an exact proposed alignment.[50]

The route of the eastern section of the North Circular Road south from its junction with the M11 at South Woodford to the junction with the A13 (the "South Woodford to Barking Relief Road") was built on the planned motorway alignment, opening in 1987. The section between South Woodford and Redbridge roundabout (A12 junction) was, for a time, temporarily designated as part of the M11.[54]

At its eastern end, Ringway 2 was planned to have crossed the River Thames at Gallions Reach in a new tunnel between Beckton and Thamesmead.[55] Although this tunnel was never built, the utility of an additional river crossing in this area continued to be recognised during the decades after the Ringway Scheme's cancellation and various proposals for an East London River Crossing have been developed, the most recent of which was the Thames Gateway Bridge, cancelled in 2008.[56]

Southern section

The South Circular Road was in the 1960s, and remains still, little more than an arbitrary route through the southern half of the city following roads that are mainly just single carriageway. The road planners considered the existing routing unsuitable for a direct upgrade so a new replacement motorway was planned for a route further to the south where the road could be constructed with less destruction of local communities.[57]

Starting in the London Borough of Greenwich at the southern end of the new tunnel in Thamesmead, the planned route for the new southern section of Ringway 2 would have first interchanged with the A2016 then headed south, first through Plumstead towards Plumstead Common and then, via open land, to Shooters Hill Road (A207). Controversially, the route was then planned to cross the ancient woodland of Oxleas Wood and the adjacent Shepheardleas Wood to connect to the "Rochester Way Relief Road" (A2) at a junction at Falconwood.[49]

Heading south from the A2, Ringway 2 would have crossed Eltham Warren Golf Course and Royal Blackheath Golf Club to reach the A20 at Mottingham where its next junction would have been constructed. Next, heading west out of the London Borough of Greenwich, the motorway crossed to Baring Road (the A2212) near Grove Park station. After this, there was a cut-and-cover tunnel underneath playing fields at Whitefoot Lane, followed by an elevated section over Bromley Road (A21).[49]

West of Bromley Road, Ringway 2 remained on an elevated alignment towards Beckenham Hill station. From here, it continued through more open land towards Lower Sydenham station where the motorway would have turned south to run alongside the railway line past New Beckenham station. It then rose to an interchange with Elmers End Road (A214).[50] Continuing along the railway line south-west of Birkbeck station, near Cambridge Road there was a proposed interchange with another of the GLC's planned motorways, the "South Cross Route to Parkway D Radial" coming south-east along the railway line from Ringway 1 at Brixton and heading to Ringway 3. Like Ringway 2 this road was never built.[50]

Ringway 2 took another elevated route crossing the railway by Goat House Bridge, before running in a cutting by South Norwood and Thornton Heath. It then passed under the Brighton Main Line up to a major junction with the M23 coming north from Mitcham. This area would have required extensive demolition. Taking the easiest alignment, the Ringway continued towards a junction with the A24 at Colliers Wood. An elevated section alongside the Sutton Loop Line between Tooting and Haydons Road took it up to the Wandle Valley. It crossed the South West Main Line to meet the A3 at a major junction in Wandsworth. From here, it continued to Putney alongside railways, before meeting the northern section at Chiswick.[50]

In 1970 the GLC expected the 25-mile (40 km) long southern ring to cost £305m, including £63m for property purchases. It would require 1,007 acres (4.08 km2) and affect 5,705 houses.[43]

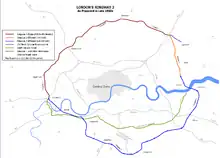

Ringway 3

Ringway 3 was a new road, the north section of which became part of the M25 from South Mimms to Swanley via the Dartford Crossing.[58] It was intended for traffic bypassing London, and was a central government scheme outside of the remit of London County Council. The route was roughly based on the earlier "D" ring designed by Patrick Abercrombie.[59] The southern section was never planned in detail, so a specific route does not exist. The section in West London was eventually built to a lower standard as the A312.[58]

Ringway 3 was planned to link the capital's outer suburbs linking areas such as Croydon, Esher, Barnet, Waltham Cross, Chigwell and Dartford.[60] Construction began on the first section of the motorway between South Mimms and Potters Bar in 1973 and the motorway was initially designated as the M16 motorway before its opening.[61][62]

While the construction of the first section was in progress, the plan for Ringways 3 and 4 were modified considerably. Broadly speaking, the northern and eastern section of Ringway 3 (from the current junction 23 of the M25 motorway with the A1 east and south to the current junction 3 with the M20) was to be built and connected to the southern and western section of Ringway 4 to create the M25. The remaining parts of the two rings became redundant.[63]

The South Mimms to Potters Bar section (junction 23 to junction 24) was opened in 1975, temporarily designated as an A-road (A1178).[64] The remaining sections of the northern Ringway 3 were constructed over the next eleven years: the M25 motorway was completed in 1986 with the opening of the Ringway 4 to Ringway 3 linking section from Micklefield to South Mimms (junction 19 to junction 23).[65]

One part of Ringway 3 in west London was eventually built as The Parkway/Hayes Bypass (A312).[66] Unlike many other Ringway proposals, it was favourable with local residents as it solved serious congestion problems. It was one of the few major road schemes approved by the GLC after Labour took control in 1981.[67]

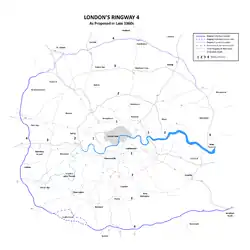

Ringway 4

Ringway 4 was more commonly known by the names "North Orbital Road" and "South Orbital Road",[68] and was first mentioned in Bressey's report.[69] The southern section became part of the M25 and M26 from Wrotham Heath to Hunton Bridge. Sections of the A405 and A414 through Hertfordshire follow its proposed route.[70] The road was planned as a combination of motorway and all-purpose dual carriageway, connecting a number of towns around the capital including Tilbury, Epping, Hoddesdon, Hatfield, St Albans, Watford, Denham, Leatherhead and Sevenoaks.[71]

Despite its name, the route of Ringway 4 did not make a complete circuit of London. It was, instead, C-shaped. The planned route started at a junction with the M20 motorway (then also being planned) near Wrotham in Kent and ran west as motorway around the capital to Hunton Bridge near Watford.[72] From Watford, the road was to head east until it met Ringway 3 near Navestock in Essex.[73]

Construction began on the first section of the motorway between Godstone and Reigate (junctions 6 to 8) in 1973 and included a junction with the M23 motorway which was under construction at the same time.[62] This opened in 1976 and the remaining sections of the southern Ringway 4 were constructed over the next ten years.[74]

While the construction of the first section was in progress, the plan for Ringways 3 and 4 was modified considerably. Broadly speaking, the motorway section of Ringway 4 was to be built and connected to the northern and eastern section of Ringway 3 (from the current M25 junction 23 with the A1 clockwise to the current junction 3 with the M20). Two additional sections of motorway were added to the plan to join the two original sections and the remaining parts of the two rings were cancelled. The south-eastern section of Ringway 4 between Wrotham and Sevenoaks was redesignated as the M26.[63]

Except for a deviation from the original plan around Leatherhead, the current M26 and the M25 between junctions 5 and 19 mostly follow the planned Ringway 4 route.[70] One short section of the dual-carriageway portion of Ringway 4 was constructed in Hoddesdon linking the town to the A10.[73]

Legacy

Ringway 1

In the central London area, only the East Cross Route and part of the West Cross Route of Ringway 1 were constructed together with the elevated Westway which links Paddington to North Kensington.[66] These were all begun and completed before the plan was cancelled. With its elevated roadway on concrete pylons flying above the streets below at rooftop height, the Westway provides a good example of how much of Ringway 1 would have appeared had it been constructed.[75][76] The East Cross route was the only part to be built in its entirety and it includes a permanently unfinished junction at Hackney Wick with the proposed North Cross Route.[47]

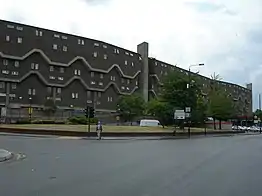

Another relic of the scheme is Southwyck House in Brixton, which was designed to shield the housing estate to its south from the noise of Ringway 1, leading to its nickname of "Barrier Block".[77]

Ringway 2

The North Circular Road section of Ringway 2 survived the cancellation of the Ringways. It remained a trunk road and a 5.5-mile (8.9 km) extension from South Woodford to Barking had land reserved from 1968.[53] This extension was approved in 1976, and opened in 1987.[53][78] Improvements have been made to the existing North Circular, so that most of it is now dual carriageway. However, these have been done in a piecemeal fashion so that the road varies in quality and capacity along its length and still has several unimproved single carriageway sections and awkward junctions.[79]

By comparison, very little has been done to improve the condition of South Circular Road and no part of the southern part of Ringway 2 was built, mainly because of the density of the residential areas through which the route runs. The road remains predominantly single carriageway throughout.[80][81]

Ringways 3 and 4

Parts of Ringways 3 and 4 were started soon after Ringway 1 was cancelled. The first section of the northern half of Ringway 3 was constructed between South Mimms and Potters Bar and opened in 1975. The first section of Ringway 4 was built between Godstone and Reigate and opened the following year.[61] Before the first of these opened, the planned north and east sections of Ringway 3 and the planned south and west sections of Ringway 4 were combined as the M25 (the northern part was initially designated as the M16 during the planning stages but opened as the M25). The remaining sections of these two circular routes were never built.[63]

M23

The M23 was particularly affected by the cancellation of the Ringways. The original plan had been to connect it to Ringway 2 near Streatham, and when the Ringway was cancelled, it was extended to meet Ringway 1 near Stockwell. Once the Ringways were cancelled completely, there seemed little point in finishing the M23 as it would drop all its traffic onto suburban streets.[82]

However, the M23 up to Streatham remained a projected route throughout the 1970s, and appeared on some road atlases of the time. The Wallington M23 Action Group campaigned for the motorway to be formally cancelled, as the inability to develop land along the line of the proposed M23 had led to planning blight in the area.[82] In 1978, the M23 north of Hooley was cancelled, to be replaced by an all-purpose relief road replacing the A23. Some residents complained, saying the motorway should still be built, and that its terminus at Hooley caused a build up of traffic there, and contributed to congestion on other roads. These proposals were cancelled in May 1980.[83]

The M23 to Streatham was briefly revived in 1985 by the GLC after the government had announced plans to spend £1.5 billion on trunk roads in London.[84] In December 2006, the A23 Coulsdon Relief Road opened to traffic. It was one of the few road proposals approved by the anti-car Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, and included a dedicated lane for buses and cycles.[85][86]

Radials

Some of the radial routes that were planned to connect to the Ringway system were built much as planned, including the M1 and M4.[87] Other radial roads, such as the M3, M11 and M23, were truncated on the outskirts of London far from their intended terminal junctions on Ringway 1.[88][89][90]

Later events

In 1979, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Transport, Kenneth Clarke, announced that the budget for developing London's road network would be cut from £500m to £170m. Several schemes which were roughly on the line of the Ringways, including Ringway 1 at Earl's Court and Fulham, and Ringway 3 at Hayes, were cancelled.[91] Upon becoming leader of the GLC in 1981, Ken Livingstone demanded an audit of all road schemes being worked on, including the remnants of Ringway plans, and cancelled many of them. One of the few schemes that did survive was the A2 Rochester Way Relief Road, the successor to the original Dover Radial. The road was constructed in a cutting instead of the originally proposed elevated build, in order to adhere to new environmental guidelines.[67]

In 2000, Transport for London (TfL) was formed, taking responsibility for all related projects in Greater London, including roads. They did not have responsibility for maintaining any motorways, so the built parts of the Westway and West and East Cross Routes were downgraded to all-purpose roads.[66] TfL has concentrated primarily on improving public transport in London and discouraging the use of private cars where practical.[92] The only new road constructed by TfL has been the A23 Coulsdon Relief Road, which opened in 2006.[93] In a significant departure from the Ringways, the road incorporates a bus lane which was proposed by Livingstone, then Mayor of London.[94]

The feedback and complaints from the Ringway plans led to an increased interest towards road protest in the United Kingdom. These included opposition to transport projects such as Twyford Down and Heathrow Terminal 5 and industrial projects such as Hinkley Point C nuclear power station.[95]

Documentation

The Ringway plans were largely made in secret, and in some cases no definitive route was proposed, which has made it difficult to work out its exact location and impact. Consequently, the project is not particularly well known to the general British public.[20] The website roads.org.uk, run by enthusiast Chris Marshall, has been praised for its level of detail in researching the Ringways, and cited as a definitive source of information.[20][96]

See also

London ring roads

Motorways

- M12 motorway – unbuilt motorway connecting M11 and Ringways 2 and 3 with Brentwood or Chelmsford

London orbital railways

- Orbirail – unimplemented

- London Overground – includes connected routes through north and south London

References

- Barbour 1905, p. 33.

- Asher 2018, pp. 12–13.

- Asher 2018, p. 13.

- Asher 2018, p. 15.

- Dnes 2019, p. 102.

- Asher 2018, p. 18.

- Asher 2018, p. 19.

- Dnes 2019, p. 101.

- Asher 2018, p. 21.

- Asher 2018, p. 23.

- Asher 2018, p. 25.

- Asher 2018, pp. 27–28.

- Asher 2018, p. 31.

- Baily, Michael (7 January 1969). "London's Motorway Box Controversy – Investing in an answer to more and more traffic". The Times. No. 57452. p. 7. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- Asher 2018, pp. 40–41.

- Asher 2018, p. 41.

- "Ringways – Background". cbrd.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- Asher 2018, pp. 53, 56.

- Asher 2018, p. 53.

- Beanland, Christopher. "London: Roads to nowhere". The Independent. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "London's lost mega-motorway: the eight-lane ring road that would have destroyed much of the city". the Guardian. 13 December 2022.

- Dnes 2019, p. 202.

- Dnes 2019, p. 214.

- Asher 2018, p. 80.

- Baily, Michael (23 October 1969). "Experts condemn London ringway scheme". The Times. No. 57698. p. 4. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- Moran 2009, p. 202.

- Asher 2018, p. 75.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Baily, Michael (19 August 1970). "Road programme cost estimated at £1,700m". The Times. No. 57948. p. 3. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- Hart 2013, p. 167.

- Asher 2018, p. 90.

- Haywood 2016, p. 178.

- Aldous, Tony (6 June 1970). "Drastic review of Ringway 1". The Times. No. 57889. p. 3. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- Hart 2013, p. 168.

- Asher 2018, p. 99.

- Hart 2013, p. 174.

- Asher 2018, pp. 101–102.

- Richards 2005, p. 45.

- Moran 2009, p. 205.

- Asher 2018, pp. 160–162.

- Asher 2018, p. 87.

- Asher 2018, pp. 160–161.

- Baily, Michael (19 August 1970). "Road programme cost estimated at £1,700m". The Times. p. 3. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Moran 2005, p. 63.

- "History". Westway Trust. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- Baker, T. F. T., ed. (1995). "Hackney: Communications". A History of the County of Middlesex. Vol. 10. London: Victoria County History. pp. 4–10. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Asher 2018, p. 161.

- Asher 2018, p. 162.

- Asher 2018, p. 163.

- Asher 2018, p. 164.

- Thomson 1969, p. 133.

- Hillman 1971, p. 86.

- Asher 2018, p. 135.

- Asher 2018, pp. 135, 137.

- "Minister decides on tunnel for Thamesmead". The Times. 12 March 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Asher 2018, pp. 151, 156, 163.

- "London Motorway Box". Hansard. 20 March 1973. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- Asher 2018, p. 165-166.

- Bayliss 1990, p. 53.

- Asher 2018, p. 112.

- Asher 2018, p. 115.

- "M25 : London Orbital Motorway – Dates". UK Motorway Archive. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Asher 2018, p. 116.

- Calder, Simon (25 September 2010). "How London got its Ring Road". The Independent. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Asher 2018, p. 121.

- Asher 2018, p. 157.

- Asher 2018, p. 136.

- Dnes 2019, p. 97.

- "Route For South Orbital Road". The Times. 26 April 1939. p. 18. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Asher 2018, p. 169.

- Asher 2018, pp. 168–169.

- Asher 2018, p. 8.

- Asher 2018, p. 168.

- Asher 2018, pp. 115, 121.

- Hart 2013, p. 166.

- Asher 2018, pp. 88, 93.

- Dnes 2019, pp. 218–219.

- "Road building and management". Hansard. 12 March 1993. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 591.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 851.

- Sir Philip Goodhart (28 July 1989). "Traffic London". Hansard. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Asher 2018, pp. 53, 105.

- Asher 2018, pp. 106–107.

- Asher 2018, p. 146.

- "Coulsdon Inner Relief Road". Mayor's Question Time. 13 December 2006. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- "Bus Lane". Mayor's Question Time. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Asher 2018, pp. 88, 135.

- Marshall, Chris. "Ringways – Western Radials – M3". CBRD. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- Marshall, Chris. "Ringways – Northern Radials – M11". CBRD. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- Marshall, Chris. "Ringways – Southern Radials – M23". CBRD. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- Webster, Philip (14 December 1979). "Bill will curb L T powers on routes". The Times. p. 5. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Dnes 2019, p. 217.

- "Coulsdon Town Centre regeneration scheme clear to progress as Coulsdon Relief Road opens". Transport for London. 18 December 2006. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Bus lane or dead end?". Sutton & Croydon Guardian. 14 March 2007. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Dnes 2019, p. 210.

- Dnes 2019, p. 13.

Bibliography

- Asher, Wayne (2018). Rings Around London – Orbital Motorways and The Battle For Homes Before Roads. ISBN 978-1-85414-421-8.

- Barbour, David; et al. (1905). Report of the Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into and Report Upon the Means of Locomotion and Transport in London. Vol. I. His Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Bayliss, Derek (1990). Orbital Motorways: Proceedings of the Conference Organized by the Institution of Civil Engineers and Held in Stratford-upon-Avon on 24–26 April 1990. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-727-71591-3.

- Dnes, Michael (2019). The Rise and Fall of London's Ringways, 1943–1973. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-00073-473-7.

- Hart, Douglas (2013). Strategic Planning in London: The Rise and Fall of the Primary Road Network. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-483-15548-7.

- Haywood, Russell (2016). Railways, Urban Development and Town Planning in Britain: 1948–2008. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-07164-8.

- Hillman, Judy (1971). Planning for London. Penguin.

- Moran, Joe (2005). Reading the Everyday. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-37216-4.

- Moran, Joe (2009). On Roads : A Hidden History. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-846-68052-6.

- Richards, Martin (2005). Congestion Charging in London: The Policy and the Politics. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-51296-2.

- Thomson, John Michael (1969). Motorways in London (Report). London Amenity and Transport Association.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-405-04924-5.

.jpg.webp)