Pterodactylus

Pterodactylus (from Greek pterodáktylos (πτεροδάκτυλος) meaning 'winged finger'[2]) is an extinct genus of pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, Pterodactylus antiquus, which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying reptile and one of the first prehistoric reptiles to ever be discovered.

| Pterodactylus Temporal range: Early Tithonian, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sub-adult type specimen of P. antiquus, Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology and Geology | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Euctenochasmatia |

| Genus: | †Pterodactylus Cuvier, 1809 |

| Type species | |

| †Ornithocephalus antiquus Sömmerring, 1812 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus synonymy

Species synonymy

| |

Fossil remains of Pterodactylus have primarily been found in the Solnhofen limestone of Bavaria, Germany, which dates from the Late Jurassic period (Tithonian stage), about 150.8 to 148.5 million years ago. More fragmentary remains of Pterodactylus have tentatively been identified from elsewhere in Europe and in Africa.[3]

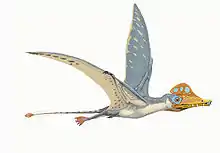

Pterodactylus was a generalist carnivore that probably fed on a variety of invertebrates and vertebrates. Like all pterosaurs, Pterodactylus had wings formed by a skin and muscle membrane stretching from its elongated fourth finger to its hind limbs. It was supported internally by collagen fibres and externally by keratinous ridges. Pterodactylus was a small pterosaur compared to other famous genera such as Pteranodon and Quetzalcoatlus, and it also lived earlier, during the Late Jurassic period, while both Pteranodon and Quetzalcoatlus lived during the Late Cretaceous. Pterodactylus lived alongside other small pterosaurs such as the well-known Rhamphorhynchus, as well as other genera such as Scaphognathus, Anurognathus and Ctenochasma. Pterodactylus is classified as an early-branching member of the ctenochasmatid lineage, within the pterosaur clade Pterodactyloidea.[4][5]

Discovery and history

The type specimen of the animal now known as Pterodactylus antiquus was the first pterosaur fossil ever to be identified. The first Pterodactylus specimen was described by the Italian scientist Cosimo Alessandro Collini in 1784, based on a fossil skeleton that had been unearthed from the Solnhofen limestone of Bavaria. Collini was the curator of the Naturalienkabinett, or nature cabinet of curiosities (a precursor to the modern concept of the natural history museum), in the palace of Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria at Mannheim.[6][7] The specimen had been given to the collection by Count Friedrich Ferdinand zu Pappenheim around 1780, having been recovered from a lithographic limestone quarry in Eichstätt.[8] The actual date of the specimen's discovery and entry into the collection is unknown however, and it was not mentioned in a catalogue of the collection taken in 1767, so it must have been acquired at some point between that date and its 1784 description by Collini. This makes it potentially the earliest documented pterosaur find; the "Pester Exemplar" of the genus Aurorazhdarcho was described in 1779 and possibly discovered earlier than the Mannheim specimen, but it was at first considered to be a fossilized crustacean, and it was not until 1856 that this species was properly described as a pterosaur by German paleontologist Hermann von Meyer.[6]

In his first description of the Mannheim specimen, Collini did not conclude that it was a flying animal. In fact, Collini could not fathom what kind of animal it might have been, rejecting affinities with the birds or the bats. He speculated that it may have been a sea creature, not for any anatomical reason, but because he thought the ocean depths were more likely to have housed unknown types of animals.[9][10] The idea that pterosaurs were aquatic animals persisted among a minority of scientists as late as 1830, when the German zoologist Johann Georg Wagler published a text on "amphibians" which included an illustration of Pterodactylus using its wings as flippers. Wagler went so far as to classify Pterodactylus, along with other aquatic vertebrates (namely plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and monotremes), in the class Gryphi, between birds and mammals.[11]

The German/French scientist Johann Hermann was the one who first stated that Pterodactylus used its long fourth finger to support a wing membrane. Back in March 1800, Hermann alerted the prominent French scientist Georges Cuvier to the existence of Collini's fossil, believing that it had been captured by the invading forces of the French Consulate and sent to collections in Paris (and perhaps to Cuvier himself) as war booty; at the time special French political commissars systematically seized art treasures and objects of scientific interest. Hermann sent Cuvier a letter containing his own interpretation of the specimen (though he had not examined it personally), which he believed to be a mammal, including the first known life restoration of a pterosaur. Hermann restored the animal with wing membranes extending from the long fourth finger to the ankle and a covering of fur (neither wing membranes nor fur had been preserved in the specimen). Hermann also added a membrane between the neck and wrist, as is the condition in bats. Cuvier agreed with this interpretation, and at Hermann's suggestion, Cuvier became the first to publish these ideas in December 1800 in a very short description.[10] However, contrary to Hermann, Cuvier was convinced the animal was a reptile.[12] The specimen had not in fact been seized by the French. Rather, in 1802, following the death of Charles Theodore, it was brought to Munich, where Baron Johann Paul Carl von Moll had obtained a general exemption of confiscation for the Bavarian collections.[6] Cuvier asked von Moll to study the fossil but was informed it could not be found. In 1809 Cuvier published a somewhat longer description, in which he named the animal Petro-Dactyle,[13] this was a typographical error however, and was later corrected by him to Ptéro-Dactyle.[10] He also refuted a hypothesis by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach that it would have been a shore bird.[13] Cuvier remarked: "It is not possible to doubt that the long finger served to support a membrane that, by lengthening the anterior extremity of this animal, formed a good wing."[14]

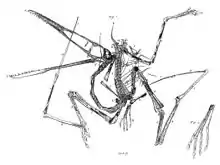

Contrary to von Moll's report, the fossil was not missing; it was being studied by Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring, who gave a public lecture about it on December 27, 1810. In January 1811, von Sömmerring wrote a letter to Cuvier deploring the fact that he had only recently been informed of Cuvier's request for information. His lecture was published in 1812, and in it von Sömmerring named the species Ornithocephalus antiquus.[15] The animal was described as being both a bat, and a form in between mammals and birds, i.e. not intermediate in descent but in "affinity" or archetype. Cuvier disagreed, and the same year in his Ossemens fossiles provided a lengthy description in which he restated that the animal was a reptile.[16] It was not until 1817 that a second specimen of Pterodactylus came to light, again from Solnhofen. This tiny specimen was that year described by von Sömmerring as Ornithocephalus brevirostris, named for its short snout, now understood to be a juvenile character (this specimen is now thought to represent a juvenile specimen of a different genus, probably Ctenochasma).[17] He provided a restoration of the skeleton, the first one published for any pterosaur.[10] This restoration was very inaccurate, von Sömmerring mistaking the long metacarpals for the bones of the lower arm, the lower arm for the humerus, this upper arm for the breast bone and this sternum again for the shoulder blades.[18] Sömmerring did not change his opinion that these forms were bats and this "bat model" for interpreting pterosaurs would remain influential long after a consensus had been reached around 1860 that they were reptiles. The standard assumptions were that pterosaurs were quadrupedal, clumsy on the ground, furred, warmblooded and had a wing membrane reaching the ankle. Some of these elements have been confirmed, some refuted by modern research, while others remain disputed.[19]

In 1815, the generic name Ptéro-Dactyle was latinized to Pterodactylus by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque.[20] Unaware of Rafinesque's publication however, Cuvier himself in 1819 latinized the name Ptéro-Dactyle again to Pterodactylus,[21] but the specific name he then gave, longirostris, has to give precedence to von Sömmerring's antiquus.[21] In 1888, English naturalist Richard Lydekker designated Pterodactylus antiquus as the type species of Pterodactylus, and considered Ornithocephalus antiquus a synonym. He also designated specimen BSP AS.I.739 as the holotype of the genus.[22]

Description

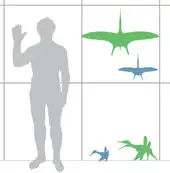

Pterodactylus is known from over 30 fossil specimens, and though most belong to juveniles, many preserve complete skeletons.[17][23] Pterodactylus antiquus was a relatively small pterosaur, with an estimated adult wingspan of about 1.04 meters (3 ft 5 in), based on the only known adult specimen, which is represented by an isolated skull.[17] Other "species" were once thought to have been smaller.[22] However, these smaller specimens have been shown to represent juveniles of Pterodactylus, as well as its contemporary relatives including Ctenochasma, Germanodactylus, Aurorazhdarcho, Gnathosaurus, and hypothetically Aerodactylus if this genus is truly valid.[24]

The skulls of adult Pterodactylus were long and thin, with about 90 narrow and conical teeth. The teeth extended back from the tips of both jaws, and became smaller farther away from the jaw tips, this was unlike the ones seen in most relatives, where teeth were absent in the upper jaw tip, and were relatively uniform in size. The teeth of Pterodactylus also extended farther back into the jaw compared to close relatives, and some were present below the front of the nasoantorbital fenestra, which is the largest opening in the skull.[17] Another autapomorphy that Pterodactylus has is that the skull and jaws were straight, which are unlike the upwardly curved jaws seen in the related ctenochasmatids.[25]

Pterodactylus, like related pterosaurs, had a crest on its skull composed mainly of soft tissues. In adult Pterodactylus, this crest extended between the back edge of the antorbital fenestra and the back of the skull. In at least one specimen, the crest had a short bony base, also seen in related pterosaurs like Germanodactylus. Solid crests have only been found on large, fully adult specimens of Pterodactylus, indicating that this was a display structure that became larger and more well developed as individuals reached maturity.[17][26] In 2013, pterosaur researcher S. Christopher Bennett noted that other authors claimed that the soft tissue crest of Pterodactylus extended backward behind the skull; Bennett himself, however, didn't find any evidence for the crest extending past the back of the skull.[17] Two specimens of P. antiquus (the holotype specimen BSP AS I 739 and the incomplete skull BMMS 7, the largest known skull of P. antiquus) have a low bony crest on their skulls; in BMMS 7 it is 47.5 mm long (1.87 inches, more or less 24% of the estimated total length of its skull) and has a maximum height of 0.9 mm (0.035 inches) above the orbit.[17] Several specimens previously referred to P. antiquus preserved evidence of the soft tissue extensions of these crests, including an "occipital lappet", a flexible, tab-like structure extending from the back of the skull. Most of these specimens have been reclassified in the related species Aerodactylus scolopaciceps, which may however be nothing more than a junior synonym. Even if Aerodactylus were valid, at least one specimen with these features is still considered to belong to Pterodactylus, BSP 1929 I 18, which has an occipital lappet similar to the proposed Aerodactylus definition, and also possesses a small triangular soft tissue crest with the peak of the crest positioned above the eyes.[17]

Paleobiology

Life history

Like other pterosaurs (most notably Rhamphorhynchus), Pterodactylus specimens can vary considerably based on age or level of maturity. Both the proportions of the limb bones, size and shape of the skull, and size and number of teeth changed as the animals grew. Historically, this has led to various growth stages (including growth stages of related pterosaurs) being mistaken for new species of Pterodactylus. Several detailed studies using various methods to measure growth curves among known specimens have suggested that there is actually only one valid species of Pterodactylus, P. antiquus.[25]

The youngest immature specimens of Pterodactylus antiquus (alternately interpreted as young specimens of the distinct species P. kochi) have a small number of teeth, as few as 15 in some, and the teeth have a relatively broad base.[23] The teeth of other P. antiquus specimens are both narrower and more numerous (up to 90 teeth are present in several specimens).[25]

Pterodactylus specimens can be divided into two distinct year classes. In the first year class, the skulls are only 15 to 45 millimeters (0.59 to 1.77 in) in length. The second year class is characterized by skulls of around 55 to 95 millimeters (2.2 to 3.7 in) long, but are still immature however. These first two size groups were once classified as juveniles and adults of the species P. kochi, until further study showed that even the supposed "adults" were immature, and possibly belong to a distinct genus. A third year class is represented by specimens of the "traditional" P. antiquus, as well as a few isolated, large specimens once assigned to P. kochi that overlap P. antiquus in size. However, all specimens in this third year class also show sign of immaturity. Fully mature Pterodactylus specimens remain unknown, or may have been mistakenly classified as a different genus.[23]

Growth and breeding seasons

The distinct year classes of Pterodactylus antiquus specimens show that this species, like the contemporary Rhamphorhynchus muensteri, likely bred seasonally and grew consistently during its lifetime. A new generation of 1st year class P. antiquus would have been produced seasonally, and reached 2nd-year size by the time the next generation hatched, creating distinct 'clumps' of similarly-sized and aged individuals in the fossil record. The smallest size class probably consisted of individuals that had just begun to fly and were less than one year old.[23][27] The second year class represents individuals one to two years old, and the rare third year class is composed of specimens over two years old. This growth pattern is similar to modern crocodilians, rather than the rapid growth of modern birds.[23]

Daily activity patterns

Comparisons between the scleral rings of Pterodactylus antiquus and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been diurnal. This may also indicate niche partitioning with contemporary pterosaurs inferred to be nocturnal, such as Ctenochasma and Rhamphorhynchus.[28]

Diet

Based on the shape, size, and arrangement of its teeth, Pterodactylus has long been recognized as a carnivore specializing in small animals. A 2020 study of pterosaur tooth wear supported the hypothesis that Pterodactylus preyed mainly on invertebrates and had a generalist feeding strategy, indicated by a relatively high bite force.[29]

Paleoecology

Specimens of Pterodactylus have been found mainly in the Solnhofen limestone (geologically known as the Altmühltal Formation) of Bavaria, Germany. The main composition of this formation is fine-grained limestone that originated mainly from the nearby towns Solnhofen and Eichstätt, which is formed by mud silt deposits.[3] The Solnhofen Limestone is a diverse Lagerstätte that contains a wide range of different creatures, including highly detailed fossilized imprints of soft bodied organisms such as jellyfishes. Abundant specimens of pterosaurs similar to Pterodactylus were also found within the formation, these include the rhamphorhynchids Rhamphorhynchus and Scaphognathus,[30] several gallodactylids such as Aerodactylus,[23] Ardeadactylus, Aurorazhdarcho and Cycnorhamphus,[7] the ctenochasmatids Ctenochasma[31] and Gnathosaurus, the anurognathid Anurognathus, the germanodactylid Germanodactylus, as well as the basal euctenochasmatian Diopecephalus.[32] Fossil remains of the dinosaurs Archaeopteryx and Compsognathus were also found within the limestone, these specimens were related to early evolution of feathers, since they were some of the only ones that had them during the Jurassic period.[33] Various lizard remains were also found alongside those of Pterodactylus, with several specimens assigned to Ardeosaurus, Bavarisaurus and Eichstaettisaurus.[34][35] Crocodylomorph specimens were widely distributed within the fossil site, most were assigned to the metriorhynchid genera Cricosaurus, Dakosaurus,[36] Geosaurus and Rhacheosaurus.[37] These genera are colloquially called as marine or sea crocodiles due to their similar built.[38] The turtle genera Eurysternum and Paleomedusa were also found within the formation.[39] Fossils of the ichthyosaur Aegirosaurus also appeared to be present in the site,[40] as well as fish remains, with many specimens assigned to ray-finned fishes such as the halecomorphs Lepidotes,[41] Propterus,[42] Gyrodus, Mesturus, Proscinetes, Caturus,[42] Ophiopsis[43] and Ophiopsiella,[41] the pachycormids Asthenocormus, Hypsocormus and Orthocormus,[44] as well as the aspidorhynchid Aspidorhynchus, and the ichthyodectid Thrissops.[45][46]

Classification

Initial classifications for Pterodactylus started when paleontologist Hermann von Meyer used the name Pterodactyli to contain Pterodactylus and other pterosaurs known at the time. This was emended to the family Pterodactylidae by Prince Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1838. However, this group has more recently been given several competing definitions.[4][47]

Beginning in 2014, researchers Steven Vidovic and David Martill constructed an analysis in which several pterosaurs traditionally thought of as archaeopterodactyloids closely related to the ctenochasmatoids may have been more closely related to the more advanced dsungaripteroids, or in some cases, fall outside both groups. Their conclusion was published in 2017, in which they placed Pterodactylus as a basal member of the suborder Pterodactyloidea.[32]

| Pterodactyloidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As illustrated below, the results of a different topology are based on a phylogenetic analysis made by Longrich, Martill, and Andres in 2018. Unlike the previous results above, they placed Pterodactylus within the clade Euctenochasmatia, resulting in a more derived position.[5]

| Archaeopterodactyloidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Formerly assigned species

Numerous species have been assigned to Pterodactylus in the years since its discovery. In the first half of the 19th century any new pterosaur species would be named Pterodactylus, which thus became a "wastebasket taxon".[32] Even after clearly different forms had later been given their own generic name, new species would be created from the very productive sites, throughout Europe and North America, often based on only slightly different material.[48]

The earliest reassignments of pterosaur species to Pterodactylus started in 1825, with the description of Rhamphorhynchus; fossil collector Georg Graf zu Münster alerted the German paleontologist Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring about several distinct fossil specimens, Sömmerring thought that they belonged to an ancient bird.[49] Further fossil preparations had uncovered teeth, to which Graf zu Münster created a skull cast. He later sent the cast to Professor Georg August Goldfuss, who recognized it as a pterosaur, specifically a species of Pterodactylus. At the time however, most paleontologists incorrectly consider the genus Ornithocephalus (lit. 'bird-head') to be the valid name for Pterodactylus, and therefore the specimen found was named as Ornithocephalus Münsteri, which was first mentioned by Graf zu Münster himself.[50] Another specimen was found and described by Graf zu Münster in 1839, he assigned this specimen to a new separate species called Ornithocephalus longicaudus; the specific name means 'long tail', in reference to the animal's tail size.[51] German paleontologist Hermann von Meyer in 1845 officially emended that the genus Pterodactylus had priority over Ornithocephalus, so he reassigned the species O. münsteri and O. longicaudus into Pterodactylus münsteri and Pterodactylus longicaudus.[52] In 1846, von Meyer created the new species Pterodactylus gemmingi based on long-tailed remains; the specific name honors the fossil collector Carl Eming von Gemming.[53] Later, in 1847, von Meyer finally erected the generic name Rhamphorhynchus (lit. 'beak snout') due to the distinctively long tails seen in the specimens found, which are much longer than those seen in Pterodactylus. He assigned the species P. longicaudus as the type species of Rhamphorhynchus, which resulted in a new combination called Rhamphorhynchus longicaudus.[54] The species R. münsteri was later changed to R. muensteri by Lydekker in 1888, due to the ICZN rule that prohibits non-standard Latin characters, such as ü, in scientific names.[22]

Beginning in 1846, many pterosaur specimens were found near the village of Burham in Kent, England by British paleontologists James Scott Bowerbank and Sir Richard Owen. Bowerbank had assigned fossil remains to two new species; the first was named in 1846 as Pterodactylus giganteus;[55] the specific name means 'the gigantic one' in Latin, in reference to the large size of the remains, and the second species was named in 1851 as Pterodactylus cuvieri, in honor of the French scientist Georges Cuvier.[56] Later in 1851, Owen named and described new pterosaur specimens that have been found yet again in England. He assigned these specimens to a new species called Pterodactylus compressirostris.[57] In 1914 however, paleontologist Reginald Hooley redescribed P. compressirostris, to which he erected the genus Lonchodectes (lit. 'lance biter'), and therefore made P. compressirostris the type species, and created the new combination L. compressirostris.[58] In a 2013 review, P. giganteus and P. cuvieri were reassigned to new genera; P. giganteus was reassigned to a genus called Lonchodraco ('lance dragon'), which resulted in a new combination called L. giganteus, and P. cuvieri was reassigned to the new genus Cimoliopterus ('chalk wing'), creating C. cuvieri.[59] Back in 1859, Owen had found remains the front part of a snout in the Cambridge Greensand, and assigned it into the species Pterodactylus segwickii; in honor of Adam Sedgwick, a British geologist.[60] This species however, was reassigned to the genus Camposipterus in 2013, therefore creating the new combination Camposipterus segwickii.[59] Later, in 1861, Owen had uncovered multiple distinctively looking fossil remains yet again in the Cambridge Greensand, these were assigned to a new species named Pterodactylus simus,[61] though the British paleontologist Harry Govier Seeley had created a separate generic name called Ornithocheirus, and reassigned P. simus as the type species, which created the combination Ornithocheirus simus.[62] Between the years 1869 and 1870, Seeley had reassigned many pterosaur species into Ornithocheirus, while also creating several new species.[62][63] Many of these species however, are now reclassified to other genera, or considered nomina dubia.[59] In 1874, further specimens were found in England, again by Owen, these ones were assigned to a new species called Pterodactylus sagittirostris,[64] this species however, was reassigned to the genus Lonchodectes in 1914 by Hooley, which resulted in an L. sagittirostris.[58] This conclusion was revised by Rigal et al. in 2017, who disagreed with Hooley's reassignment, and therefore created the genus Serradraco, which afterwards resulted in a new combination called S. sagittirostris.[65]

Assigning new pterosaur species to Pterodactylus was not only common in Europe, but also in North America; paleontologists such as Othniel Charles Marsh in 1871 for example, described several toothless pterosaur specimens, which were accompanied by teeth that belonged to the fish Xiphactinus, which Marsh assumed that these teeth belonged to the pterosaur specimens he found, since all pterosaurs discovered at the time had teeth. He then assigned these specimens to a new species called "Pterodactylus oweni", but this was changed to Pterodactylus occidentalis because "P. oweni" was found to have been preoccupied by a pterosaur species described with the same name back in 1864 by Seeley.[66][67] In 1872, American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope also found various pterosaur specimens in North America, he assigned these to two new species known as Ornithochirus umbrosus and Ornithochirus harpyia, Cope attempted to assign the specimens he found to the genus Ornithocheirus, but misspelled forgetting the 'e'.[68] In 1875 however, Cope reassigned the species O. umbrosus and O. harpyia into Pterodactylus umbrosus and Pterodactylus harpyia, though these species had been considered nomina dubia ever since.[69][67] Paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston unearthed the first skull of the pterosaur, and found that the animal was toothless,[67] this made Marsh create the genus Pteranodon (lit. 'toothless wing'), and therefore reassigned all the American pterosaur species, including the ones that he named, from Pterodactylus to Pteranodon.[70]

Later, in the 1980s, subsequent revisions by Peter Wellnhofer had reduced the number of recognized species to about half a dozen. Many species assigned to Pterodactylus had been based on juvenile specimens, and subsequently been recognized as immature individuals of other species or genera. By the 1990s it was understood that this was even true for part of the remaining species. P. elegans, for example, was found by numerous studies to be an immature Ctenochasma.[25] Another species of Pterodactylus originally based on small, immature specimens was P. micronyx. However, it has been difficult to determine exactly of what genus and species P. micronyx might be the juvenile form. Stéphane Jouve, Christopher Bennett and others had once suggested that it probably belonged either to Gnathosaurus subulatus or one of the species belonging to Ctenochasma,[24][25] though after additional research Bennett assigned it to the genus Aurorazhdarcho.[17] Another species with a complex history is P. longicollum, named by von Meyer in 1854, based on a large specimen with a long neck and fewer teeth. Many researchers, including David Unwin, have found P. longicollum to be distinct from P. kochi and P. antiquus. Unwin found P. longicollum to be closer to Germanodactylus and therefore requiring a new genus name.[4] It has sometimes been placed in the genus Diopecephalus because Harry Govier Seeley based this genus partly on the P. longicollum material. However, it was shown by Bennett that the type specimen later designated for Diopecephalus was a fossil belonging to P. kochi, and no longer thought to be separate from Pterodactylus. Diopecephalus is therefore a synonym of Pterodactylus, and as such is unavailable for use as a new genus for "P." longicollum.[71] "P." longicollum was eventually made the type species of a separate genus Ardeadactylus.[17]

Controversial species

The only well-known and well-supported species left by the first decades of the 21st century were P. antiquus and P. kochi. However, most studies between 1995 and 2010 found little reason to separate even these two species, and treated them as synonymous.[4] More recent studies of pterosaur relationships have found anurognathids and pterodactyloids to be sister groups, which would limit the more inclusive group Caelidracones to just two clades.[72][71] In 1996, Bennett suggested that the differences between specimens of P. kochi and P. antiquus could be explained by differences in age, with P. kochi (including specimens alternately classified in the species P. scolopaciceps) representing an immature growth stage of P. antiquus. In a 2004 paper, Jouve used a different method of analysis and recovered the same result, showing that the "distinctive" features of P. kochi were age-related, and using mathematical comparison to show that the two forms are different growth stages of the same species.[25] An additional review of the specimens published in 2013 demonstrated that some of the supposed differences between P. kochi and P. antiquus were due to measurement errors, further supporting their synonymy.[17]

By the 2010s, a large body of research had been developed based on the idea that P. kochi and P. scolopaciceps were early growth stages of P. antiquus. However, in 2014, two scientists began publishing research that challenged this paradigm. Steven Vidovic and David Martill concluded that differences between specimens of P. kochi, P. scolopaciceps, and P. antiquus, such as different lengths of neck vertebrae, thinner or thicker teeth, more rounded skulls, and how far the teeth extended back in the jaws, were significant enough to separate them into three distinct species. Vidovic and Martill also performed a phylogenetic analysis which treated all relevant specimens as distinct units, and found that the P. kochi type specimen did not form a natural group with that of P. antiquus. They concluded that the genus Diopecephalus could be returned to use to distinguish "P". kochi from P. antiquus. They named the new genus Aerodactylus for P. scolopaciceps as well. So, what Bennett considered early growth stages of one species, Vidovic and Martill considered representatives of new species.[48][32]

In 2017, Bennett challenged this hypothesis, he claimed that while Vidovic and Martill had identified real differences between these three groups of specimens, they had not provided any rationale that the differences were enough to distinguish them as species, rather than just individual variation, growth changes, or simply due to crushing and distortion during the fossilization process. Bennett pointed in particular to the data used to distinguish Aerodactylus, which was so different from the data for related species, it might be due to an unnatural assemblage of specimens. As a result, Bennett continued to consider Diopecephalus and Aerodactylus simply as year-classes of immature Pterodactylus antiquus.[73]

List of species

During its over-200-year history, the various species of Pterodactylus have gone through a number of changes in classification and thus have acquired a large number of synonyms. Additionally, a number of species assigned to Pterodactylus are based on poor remains that have proven difficult to assign to one species or another and are therefore considered nomina dubia (lit. 'doubtful names'). The following list includes names that were used to identify new pterosaur species that now have been reclassified, or until recently thought to be pertaining to Pterodactylus proper, and names based on other material that has as yet not been assigned to other genera. This list also includes species that are nomina nuda ('naked names'), which are species that were not published formally. Species that are nomina oblita ('forgotten names') are the ones that have been disused, and species that are nomina rejecta ('rejected names') are the ones that have been rejected because a more preferable name had been accepted instead.[22][74]

List of species | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cultural significance

Pterodactylus is regarded as one of the most iconic prehistoric creatures, with multiple appearances in books, movies, as well as television series and several videogames. The informal name "pterodactyl" is sometimes used to refer to any kind of animal belonging to the order Pterosauria, though most of the times to Pterodactylus, as it's the most well-known member of the group.[76] The popular aspect of Pterodactylus consists of an elongated head crest, and potentially large wings. Studies of Pterodactylus however, conclude that it may even lack a bony cranial crest, though several analysis have proven that Pterodactylus may in fact have a crest made up of soft tissue instead of bone.[17]

Another appearance of Pterodactylus-like creatures is in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. In this novel, the Nazgûl, introduced as the Black Riders, are nine characters who rode flying monsters that looked similarly built to Pterodactylus. Christopher Tolkien, the son of the author, described the flying monsters as "Nazgûl-birds"; his father described the appearance of the steeds as somewhat "pterodactylic", and acknowledged that these were obviously "new mythology".[77][78]

References

- Fischer von Waldheim, Gotthelf (1813). Zoognosia tabulis synopticis illustrata : in usum praelectionum mperalis Medico-Chirurgicae Mosquenis edita. Vol. 1. Mosquae [Moscow]: Typis Nicolai S. Vsevolozsky. p. 466.

- Gudger, E.W. (1944). "The Earliest Winged Fish-Catchers". The Scientific Monthly. 59 (2): 120–129. Bibcode:1944SciMo..59..120G. JSTOR 18398.

- Schweigert, G. (2007). "Ammonite biostratigraphy as a tool for dating Upper Jurassic lithographic limestones from South Germany – first results and open questions" (PDF). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 245 (1): 117–125. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2007/0245-0117.

- Unwin, D. M. (2003). "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217 (1): 139–190. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.217..139U. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.11. S2CID 86710955.

- Longrich, N.R.; Martill, D.M.; Andres, B. (2018). "Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary". PLOS Biology. 16 (3): e2001663. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001663. PMC 5849296. PMID 29534059.

- Ősi, A.; Prondvai, E.; Géczy, B. (2010). "The history of Late Jurassic pterosaurs housed in Hungarian collections and the revision of the holotype of Pterodactylus micronyx Meyer 1856 (a 'Pester Exemplar')". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 343 (1): 277–286. Bibcode:2010GSLSP.343..277O. doi:10.1144/SP343.17. S2CID 129805068.

- Unwin, David M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. p. 246. ISBN 0-13-146308-X.

- Brougham, Henry P. (1844). "Dialogues on instinct; with analytical view of the researches on fossil osteology". Knight's Weekly Volume for All Readers. 19.

- Collini, C A. (1784). "Sur quelques Zoolithes du Cabinet d'Histoire naturelle de S. A. S. E. Palatine & de Bavière, à Mannheim". Acta Theodoro-Palatinae Mannheim (in French). 5 Physicum: 58–103 (1 plate).

- Taquet, P.; Padian, K. (2004). "The earliest known restoration of a pterosaur and the philosophical origins of Cuvier's Ossemens Fossiles". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 3 (2): 157–175. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2004.02.002.

- Wagler, Johann Georg (1830). Natürliches System der Amphibien : mit vorangehender Classification der Säugethiere und Vögel : ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden Zoologie (in German). München.

- Cuvier, G. (1801). "Extrait d'un ouvrage sur les espèces de quadrupèdes dont on a trouvé les ossemens dans l'intérieur de la terre". Journal de Physique, de Chimie et d'Histoire Naturelle (in French). 52: 253–267.

Reptile volant

- Cuvier, G. (1809). "Mémoire sur le squelette fossile d'un reptile volant des environs d'Aichstedt, que quelques naturalistes ont pris pour un oiseau, et dont nous formons un genre de Sauriens, sous le nom de Petro-Dactyle". Annales du Muséum national d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris. 13: 424–437.

- Cuvier, G. (1809), p. 436 : "II n'est guère possible de douter que ce long doigt n'ait servi à supporter une membrane qui formoit [sic] à l'animal, d'après la longueur de l'extrémité antérieure, une aile bien plus puissante que celle du dragon, et au moins égale en force à celle de la chauve-souris."

- von Sömmerring, S. T. (1812). "Über einen Ornithocephalus oder über das unbekannten Thier der Vorwelt, dessen Fossiles Gerippe Collini im 5. Bande der Actorum Academiae Theodoro-Palatinae nebst einer Abbildung in natürlicher Grösse im Jahre 1784 beschrieb, und welches Gerippe sich gegenwärtig in der Naturalien-Sammlung der königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu München befindet: vorgelesen in der mathematisch-physikalischen Classe am 27. Dec. 1810 und Nachtrag vorgelesen am 8. April 1811". Denkschriften der Königlichen Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. München. 3: 89–158.

- Cuvier, G. (1812). "Article V – Sur le squelette fossile d'un reptile volant des environs d'Aichstedt, que quelques naturalistes ont pris pour un oiseau et dont nous formons un genre de sauriens, sous le nom de ptéro-dactyle". Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes : où l'on rétablit les caractères de plusieurs espèces d'animaux que les révolutions du globe paroissent avoir détruites (in French). Vol. Tome 4. Paris: Deterville. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.60807.

- Bennett, S. Christopher (2013). "New information on body size and cranial display structures of Pterodactylus antiquus, with a revision of the genus". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 87 (2): 269–289. doi:10.1007/s12542-012-0159-8. S2CID 83722829.

- von Sömmerring, S.T. (1817). "Ueber einen Ornithocephalus brevirostris der Vorwelt". Denkschriften der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (in German). 6: 89–104.

- Padian, K. (1987). "The case of the bat-winged pterosaur. Typological taxonomy and the influence of pictorial representation on scientific perception". In Czerkas, S. J.; Olson, E. C. (eds.). Dinosaurs past and present. Vol. 2. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in association with University of Washington Press, Seattle and London. pp. 65–81. ISBN 978-0-938644-23-1.

- Rafinesque, C.S. (1815). Analyse de la nature, ou tableau de l'univers et des corps organisés (L'Imprimerie de Jean Barravecchia ed.). p. 224.

- Cuvier, G. (1819). "Pterodactylus longirostris". In Oken, Lorenz (ed.). Isis (oder Encyclopädische Zeitung) von Oken (in German). Jena : Expedition der Isis. pp. 1126, 1788.

- Lydekker, Richard (1888). Catalogue of Fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum (Natural History). Part I. Containing the Orders Ornithosauria, Crocodilia, Dinosauria, Squamata, Rhynchocephalia and Pterosauria. Taylor and Francis. pp. 2–37.

- Bennett, S.C. (1996). "Year-classes of pterosaurs from the Solnhofen Limestone of Germany: Taxonomic and Systematic Implications". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (3): 432–444. doi:10.1080/02724634.1996.10011332.

- Bennett, S.C. (2002). "Soft tissue preservation of the cranial crest of the pterosaur Germanodactylus from Solnhofen". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0043:STPOTC]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524192. S2CID 86308635.

- Jouve, S. (2004). "Description of the skull of a Ctenochasma (Pterosauria) from the latest Jurassic of eastern France, with a taxonomic revision of European Tithonian Pterodactyloidea". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3): 542–554. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0542:DOTSOA]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86019483.

- Frey, E.; Martill, D.M. (1998). "Soft tissue preservation in a specimen of Pterodactylus kochi (Wagner) from the Upper Jurassic of Germany". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 210 (3): 421–441. doi:10.1127/njgpa/210/1998/421.

- Wellnhofer, Peter (1970). Die Pterodactyloidea (Pterosauria) der Oberjura-Plattenkalke Süddeutschlands (PDF). Vol. 141. Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Wissenschaftlichen Klasse, Abhandlungen. p. 133.

- Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology" (PDF). Science. 332 (6030): 705–8. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..705S. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820. S2CID 33253407. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2019.

- Bestwick, J., Unwin, D.M., Butler, R.J. et al. Dietary diversity and evolution of the earliest flying vertebrates revealed by dental microwear texture analysis. Nat Commun 11, 5293 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19022-2

- Bennett, S. C. (2004). "New information on the pterosaur Scaphognathus crassirostris and the pterosaurian cervical series". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (Supplement 003): 38A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2004.10010643. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 220415208.

- Bennett, S.C. (2007). "A review of the pterosaur Ctenochasma: taxonomy and ontogeny". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 245 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2007/0245-0023.

- Vidovic, Steven U.; Martill, David M. (2017). "The taxonomy and phylogeny of Diopecephalus kochi (Wagner, 1837) and "Germanodactylus rhamphastinus" (Wagner, 1851)" (PDF). Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455 (1): 125–147. Bibcode:2018GSLSP.455..125V. doi:10.1144/SP455.12. S2CID 219204038.

- Fastovsky, D.E.; Weishampel, D.B. (2005). "Theropoda I: nature red in tooth and claw". In Fastovsky, D.E.; Weishampel, D.B. (eds.). The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 265–299. doi:10.1017/9781316471623.009. ISBN 978-0-521-81172-9.

- Hoffstetter, R. (1966). "A propos des genres Ardeosaurus et Eichstaettisaurus (Reptilia, Sauria, Gekkonoidea) du Jurassique Supèrieur de Franconie" [On the genera Ardeosaurus and Eichstaettisaurus (Reptilia, Sauria, Gekkonoidea) from the Upper Jurassic of France]. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 8 (4): 592–595. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.S7-VIII.4.592.

- Evans, S.E. (1994). "The Solnhofen (Jurassic: Tithonian) lizard genus Bavarisaurus: new skull material and a reinterpretation". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 192: 37–52.

- Brandalise de Andrade, Marco; Young, Mark T.; Desojo, Julia B.; Brusatte, Stephen L. (2010). "The evolution of extreme hypercarnivory in Metriorhynchidae (Mesoeucrocodylia: Thalattosuchia) based on evidence from microscopic denticle morphology". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1451–1465. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501442. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 83985855.

- Brandalise de Andrade, Marco; Young, Mark T. (2008). "High diversity of thalattosuchian crocodylians and the niche partition in the Solnhofen Sea". The 56th Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy: 14–15. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011.

- Young, Mark T.; Brusatte, Stephen L.; de Andrade, Marco Brandalise; Desojo, Julia B.; Beatty, Brian L.; Steel, Lorna; Fernández, Marta S.; Sakamoto, Manabu; Ruiz-Omeñaca, Jose Ignacio; Schoch, Rainer R. (September 18, 2012). Butler, Richard J. (ed.). "The Cranial Osteology and Feeding Ecology of the Metriorhynchid Crocodylomorph Genera Dakosaurus and Plesiosuchus from the Late Jurassic of Europe". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e44985. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...744985Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044985. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3445579. PMID 23028723.

- Joyce, Walter G. (2003). "A new Late Jurassic turtle specimen and the taxonomy of Palaeomedusa testa and Eurysternum wagleri" (PDF). PaleoBios. 23 (3): 1–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2015.

- Bardet, Nathalie; Fernández, Marta S. (2000). "A new ichthyosaur from the Upper Jurassic lithographic limestones of Bavaria". Journal of Paleontology. 74 (3): 503–511. doi:10.1017/S0022336000031760. ISSN 0022-3360.

- Lambers, Paul H. (1999). "The actinopterygian fish fauna of the Late Kimmeridgian and Early Tithonian 'Plattenkalke' near Solnhofen (Bavaria, Germany): state of the art". Geologie en Mijnbouw. 78 (2): 215–229. doi:10.1023/A:1003855831015. hdl:1874/420683. S2CID 127676896.

Table 1: List of actinopterygians from the Solnhofen lithographic limestone – Halecomorphi; 'Amiidae' and 'Ophiopsidae'" (p. 216)

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- Lane, Jennifer A.; Ebert, Martin (2015). "A taxonomic reassessment of Ophiopsis (Halecomorphi, Ionoscopiformes), with a revision of Upper Jurassic species from the Solnhofen Archipelago, and a new genus of Ophiopsidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (1): e883238. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.883238. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 86350086.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 38. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Frey, E.; Tischlinger, H. (2012). "The Late Jurassic pterosaur Rhamphorhynchus, a frequent victim of the ganoid fish Aspidorhynchus?". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e31945. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...7E1945F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031945. PMC 3296705. PMID 22412850.

- Nybelin, Orvar (1964). Versuch einer taxonomischen Revision der jurassischen Fischgattung Thrissops Agassiz (in German). Göteborg: Wettergren and Kerber. OCLC 2672427.

- Kellner, Alexander W. A. (2003). "Pterosaur phylogeny and comments on the evolutionary history of the group". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. 217 (1): 105–137. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.217..105K. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.10. ISSN 0305-8719. S2CID 128892642.

- Vidovic, S. U.; Martill, D. M. (2014). "Pterodactylus scolopaciceps Meyer, 1860 (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Upper Jurassic of Bavaria, Germany: The Problem of Cryptic Pterosaur Taxa in Early Ontogeny". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e110646. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k0646V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110646. PMC 4206445. PMID 25337830.

- Witton, Mark (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15061-1.

- Münster, Georg Graf zu (1830). Nachtrag zu der Abhandlung des professor Goldfuss ueber den Ornithocephalus Münsteri (Goldf.). Bayreuth: F. C. Birner.

- Münster, Georg Graf zu (1839). "Über einige neue Versteinerungen in der lithographischen Schiefer von Baiern". Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde. Stuttgart: E. Schweizerbart's Verlagshandlung. pp. 676–682.

- von Meyer, Hermann (1845). "System der fossilen Saurier" [Taxonomy of fossil saurians]. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde (in German). Stuttgart: E. Schweizerbart's Verlagshandlung: 278–285.

- von Meyer, Hermann (1846). "Pterodactylus (Rhamphorhynchus) gemmingi aus dem Kalkschiefer von Solenhofen". Palaeontographica. Cassel (published 1851). 1: 1–20.

- von Meyer, Hermann (1847). Homoeosaurus maximiliani und Rhamphorhynchus (Pterodactylus) longicaudus: Zwei fossile Reptilien aus dem Kalkschiefer von Solenhofen (in German). Frankfurt: S. Schmerber'schen buchhandlung.

- Bowerbank, J.S. (1846). "On a new species of pterodactyl found in the Upper Chalk of Kent (Pterodactylus giganteus)". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 2 (1–2): 7–9. doi:10.1144/gsl.jgs.1846.002.01-02.05. S2CID 129389179.

- Bowerbank, J.S. (1851). "On the pterodactyles of the Chalk Formation". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 19: 14–20. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1851.tb01125.x.

- Owen, R. (1851). Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Cretaceous Formations. The Palaeontographical Society 5(11):1–118.

- Hooley, Reginald Walter (1914). "On the Ornithosaurian genus Ornithocheirus, with a review of the specimens from the Cambridge Greensand in the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13 (78): 529–557. doi:10.1080/00222931408693521. ISSN 0374-5481.

- Rodrigues, T.; Kellner, A. (2013). "Taxonomic review of the Ornithocheirus complex (Pterosauria) from the Cretaceous of England". ZooKeys (308): 1–112. doi:10.3897/zookeys.308.5559. PMC 3689139. PMID 23794925.

- Owen, R. (1859). Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Cretaceous formations. Supplement no. I. Palaeontographical Society, London, p. 19

- Martill, David. (2010). The early history of pterosaur discovery in Great Britain. Geological Society of London, Special Publications. 343. 287–311. doi:10.1144/SP343.18.

- Seeley, Harry Govier (1869). "Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria, and Reptilia, from the Secondary System of Strata, arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 5 (27): 225–226. doi:10.1080/00222937008696143. ISSN 0374-5481.

- Seeley, H.G. (1870). "The Ornithosauria: an Elementary Study of the Bones of Pterodactyles". Cambridge: 112–128.

- Owen, R. 1874. "A Monograph on the Fossil Reptilia of the Mesozoic Formations. 1. Pterosauria." The Palaeontographical Society Monograph 27: 1–14

- Rigal, S.; Martill, D. M.; Sweetman, S. C. (2017). "A new pterosaur specimen from the Upper Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation (Cretaceous, Valanginian) of southern England and a review of Lonchodectes sagittirostris (Owen 1874)". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455: 221–232. doi:10.1144/SP455.5. S2CID 133080548.

- Marsh, O.C. (1871). "Note on a new and gigantic species of Pterodactyle". American Journal of Science. 3. 1 (6): 472.

- Witton, M.P. (2010). "Pteranodon and beyond: The history of giant pterosaurs from 1870 onwards. Geological Society of London Special Publications". 343: 313–323.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Cope, E. D. (1872). "On two new Ornithosaurians from Kansas". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 12 (88): 420–422. JSTOR 981730.

- Cope, E. D. (1875). "The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous formations of the West". Report, U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories (Hayden). 2: 302 pp., 57 pls.

- Marsh, O.C. (1876a). "Notice of a new sub-order of Pterosauria". American Journal of Science. Series 3. 11 (65): 507–509. Bibcode:1876AmJS...11..507M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-11.66.507. S2CID 130203580.

- Bennett, S.C. (2006). "Juvenile specimens of the pterosaur Germanodactylus cristatus, with a review of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 872–878. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[872:JSOTPG]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86460861.

- Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103 (3–4): 383–398. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303. S2CID 84617119.

- Bennett, S.C. (2017). "New smallest specimen of the pterosaur Pteranodon and ontogenetic niches in pterosaurs". Journal of Paleontology. 92 (2): 1–18. doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.84. S2CID 90893067.

- Arnold, Caroline (2014). Pterosaurs: Rulers of the Skies in the Dinosaur Age. StarWalk Kids Media. ISBN 978-1-63083-412-8.

- Oken, Lorenz (1816). Okens Lehrbuch der Naturgeschichte. Vol. 3. Leipzig: August Schmid und Comp. pp. 312–314.

- Naish, Darren. "Pterosaurs: Myths and Misconceptions". Pterosaur.net. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, #211 to Rhona Beare, October 14, 1958

- Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, #100 to Christopher Tolkien, May 29, 1945, expressing his "loathing" for the Royal Air Force: "My sentiments are more or less those that Frodo would have had if he discovered some Hobbits learning to ride Nazgûl-birds, 'for the liberation of the Shire'."

External links

Media related to Pterodactylus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pterodactylus at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Pterodactylus at Wikispecies

Data related to Pterodactylus at Wikispecies