Slovakia in the Roman era

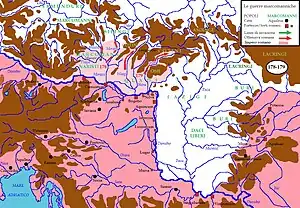

Slovakia was partly occupied by Roman legions for a short period of time.[1] Marcomannia was a proposed province of the Roman Empire that Emperor Marcus Aurelius planned to establish in this territory.[2] It was inhabited by the Germanic tribes of Marcomanni and Quadi, and lay in the western parts of the modern states and Slovakia and the Czech Republic (Moravia). Part of the area was occupied by the Romans under Marcus Aurelius between 174 AD and 180 AD. His successors abandoned the project, but the people of the area became steadily Romanized during the next two centuries. The Roman influence was disrupted with the invasions of Attila starting around 434 AD and as Slavic people later began to move into the area.[3]

| History of Slovakia |

|---|

|

|

|

Characteristics

After the creation of the fortified limes on the Danube river, the Roman Empire tried to expand in central Europe, mainly during the emperor Marcus Aurelius's rule in the second century.

It was an initiative that resulted in an ephemeral conquest of the Germanic tribes living in present-day western Slovakia, the Quadi and the Marcomanni, during the so-called Marcomannic Wars.

Under Augustus, the Romans and their armies initially occupied only a thin strip of the right bank of the Danube and a very small part of south-western Slovakia (Celemantia, Gerulata, Devín Castle). Tiberius wanted to conquer all Germania up to the Elbe river and in 6 AD dispatched a military expedition from the fort of Carnuntum to Mušov and beyond,[4] but was forced to stop the conquest because of a revolt in Pannonia.

Only in 174 AD did the emperor Marcus Aurelius penetrate deeper into the river valleys of the Váh, Nitra and Hron, where there are some Roman marching camps like Laugaricio.[5] On the banks of the Hron he wrote his philosophical work Meditations[6] The small Roman forts of Zavod and Suchohrad on the Morava river show an intention of penetrating toward northern Bohemia-Moravia[7] and the Oder river (and perhaps southern Poland [8]).

The latest archaeological discoveries which have located new Roman enclosures in the surroundings of Brno led to the conclusion that the advance of Roman troops from Carnuntum could have run further to the north-east, into the region of the Polish-Slovak border. Indeed, recent archaeological excavations and aerial surveying have shown further locations in northeast Moravia: three temporary Roman camps (possibly connected to the Laugaricio fort) situated in the foreland of the so-called Moravian Gate (Olomouc-Neředín, Hulín-Pravčice, Osek) have been partly corroborated, the former two clearly by digging.[9]

Marcus Aurelius wanted to create a new Roman province called Marcomannia in those conquered territories, but his death put an end to the project. His successors abandoned these territories, but – with the exception of Valentinian I – maintained a relatively friendly relationship with the barbarians living there (who enjoyed a degree of "cultural Romanization" that can be seen in some buildings in present-day Bratislava Region in Stupava[10]).

Indeed, the Romanization of the barbarian population continued into the late Roman period (181-380 AD). Many Roman buildings (with plenty of trade evidence of Roman civilization) appeared on the territory of south-western Slovakia (Dúbravka, Cífer - Pác, Veľký Kýr[11]) in the relatively peaceful period of the 3rd and 4th centuries. These were probably residences of the pro-Roman Quadian (and maybe Marcomannic) aristocracy.

Romans in the late fourth century were able to bring Christianity into the area: the Germanic population of the Marcomanni converted when Fritigil, their queen, met a Christian traveller from the Roman Empire shortly before 397 AD. He talked to her of Ambrose, the formidable bishop of Milan (Italy). Impressed by what she heard, the queen converted to Christianity.[12] In the Roman ruins of Devín Castle, the first Christian church located north of the Danube has been identified, probably built in the early fifth century.

A few years later Attila devastated the area and started the mass migrations that destroyed the Western Roman Empire. Meanwhile, the area was beginning to be occupied by Slavic tribes.

Indeed, the first written source suggesting that Slavic tribes established themselves in what is now Slovakia is connected to the migration of the Germanic Heruli from the Middle Danube region towards Scandinavia in 512.[13] In that year, according to Procopius, they first passed "through the land of the Slavs", most probably along the river Morava.[14] A cluster of archaeological sites in the valleys of the rivers Morava, Váh and Hron also suggests that at the latest the earliest Slavic settlements appeared in the territory around 500 AD.[15] They are characterized by vessels similar to those of the "Mogiła" group of southern Poland and having analogies in the "Korchak" pottery of Ukraine.[16]

In those same years the Roman presence disappeared from the area of Danubian limes, but there is a remote possibility that Romans and those early Slovak tribes interacted commercially.

Background

The reign of Augustus (27 BC - 14 AD) began a long period known as the Pax Romana, or Roman peace. Despite continuous wars on the frontiers, and one year-long civil war over the imperial succession, the Mediterranean world remained at peace for more than two centuries. Augustus enlarged the empire dramatically, annexing Egypt, Dalmatia, Pannonia, and Raetia, expanded possessions in Africa, and completed the conquest of Hispania. By the end of his reign, the armies of Augustus had conquered the Alpine regions of Raetia and Noricum (modern Switzerland, Bavaria, Austria, Slovenia), Illyricum and Pannonia (modern Albania, Croatia, Hungary, Serbia, etc.).[17]

The Romans and their armies occupied a narrow strip of the right bank of the Danube and a very small part of south-western Slovakia (Celemantia, Gerulata, Devín Castle). Augustus's successor Tiberius (14 AD - 37 AD) wanted to conquer all Germania up to the Elbe river and in 6 AD started a military expedition from the fort of Carnuntum to Mušov and beyond.[18] However, he was forced to abandon the conquest because of a revolt in Pannonia.[19]

The expanding Roman Empire established and maintained a series of outposts around and just north of the Danube. The largest of these were Carnuntum, whose remains are on the main road halfway between Vienna and Bratislava, and Brigetio (present-day Szőny at the Slovak-Hungarian border). The Romans supported the client kingdom of the Quadi, a Germanic tribe, to maintain peace in the Middle Danube area.[20] The Marcomanni were another Germanic tribe said by Tacitus to "stand first in strength and renown".[21] Maroboduus, who ruled in the first quarter of the first century AD, was a powerful ruler with an extensive empire based on modern-day Bohemia that included many smaller tribes. He was fully independent of Rome.[22] Later the Marcomanni also became clients of the Romans.[21]

The Romans built forts in the province of Pannonia, bordering on Marcomannic territory, in the earlier Flavian period (69 AD - 96 AD). These included Arrabona and Brigetio in modern Hungary. They built various military installations in the Middle Danube area at the end of the first century including the fort of Gerulata. This fort, rebuilt several times before the end of the fourth century, is still visible in the village of Rusovce in southern Bratislava.[20]

Marcomannic Wars

Germanic attacks, 166–171

Pannonia was invaded in late 166 or early 167 by a force of 6,000 Langobardi and Ubii. This invasion was quickly defeated by the Roman cavalry and infantry. In the aftermath the military governor of Pannonia, Iallius Bassus, initiated negotiations with 11 tribes. The Marcomannic king Ballomar, a Roman client, acted as the main negotiator for the tribes. In 168 the Marcomanni and Victohali again crossed the Danube into Pannonia, but when a Roman army advanced to Carnuntum they withdrew, promising good conduct.[23]

A much more serious invasion occurred in 169, when Ballomar formed a coalition of Germanic tribes that crossed the Danube and won a decisive victory over a force of 20,000 Roman soldiers near Carnuntum. Ballomar then led the larger part of his host southwards towards Italy, while the remainder ravaged Noricum. The Marcomanni razed Opitergium (Oderzo) and besieged Aquileia.[24] The army of praetorian prefect Furius Victorinus tried to relieve the city, but was defeated and its general slain. The Romans reorganized, brought in fresh troops and managed to eventually evict the invaders from Roman territory by the end of 171.[25]

Roman counter-offensives, 172–174

Marcus Aurelius started the invasion of what are now Slovak territories in 172 AD, when the Romans crossed the Danube into Marcomannic territory. Although few details are known, the Romans achieved success, subjugating the Marcomanni and their allies, the Varistae or Naristi and the Cotini. After the 172 campaigning season Marcus and Commodus were both given the title "Germanicus", and coins were minted with the inscription "Germania subacta" (subjugated Germany). The Marcomanni were subjected to a harsh treaty.[26]

In 173 AD the Romans campaigned against the Quadi, who had broken their treaty and assisted their kin, the Marcomanni. The Quadi were defeated and subdued.[27] In 174 AD Marcus Aurelius penetrated deeper into the river valleys of Váh, Nitra and Hron, where there are Roman marching camps like Laugaricio.[28] On the banks of the Hron he wrote his philosophical work "Meditations".[6] In the same year, the legions of Marcus Aurelius again marched against the Quadi. In response, the Quadi deposed their pro-Roman king, Furtius, and installed his rival Ariogaesus in his place. Marcus Aurelius refused to recognize Ariogaesus, and after his capture exiled him to Alexandria.[29] By late 174, the subjugation of the Quadi was complete.[30]

Rebellion of Avidius Cassius, 175–176

Marcus Aurelius may have intended to campaign against the remaining tribes of the area that is now western Slovakia and Bohemia, and together with his recent conquests establish two new Roman provinces, Marcomannia and Sarmatia, but whatever his plans, they were cut short by the rebellion of Avidius Cassius in the East.[2] Marcus Aurelius marched eastwards with his army, accompanied by auxiliary detachments of Marcomanni, Quadi, and Naristi under the command of Marcus Valerius Maximianus.[31] After the successful suppression of Cassius' revolt, the emperor returned to Rome for the first time in nearly 8 years. On 23 December 176 AD, together with his son Commodus, he celebrated a joint triumph for his German victories ("de Germanis" and "de Sarmatis"). In commemoration of this, the Aurelian Column was erected, in imitation of Trajan's Column.[32]

Second Marcomannian campaign, 177–180

In 177 AD, the Quadi again rebelled, soon followed by their neighbours, the Marcomanni. After delays, Marcus Aurelius headed north on 3 August 178 to begin his second Germanic campaign, too late for serious action that year.[33] Publius Tarrutenius Paternus was given supreme command in the campaigning season of 179. The main enemy seems to have been the Quadi and results were positive.[34] The next year, on 17 March 180, the emperor died at Vindobona (modern Vienna), or perhaps at Bononia on the Danube, to the north of Sirmium. He probably died of plague. His death happened just before the campaigning season began, and when his dream of creating the provinces of Marcomannia and Sarmatia seemed close to fulfillment.[35]

Subsequent Roman influence

When Commodus succeeded Marcus Aurelius he had little interest in pursuing the war. Against the advice of his senior generals, he negotiated a peace treaty with the Marcomanni and the Quadi, where he agreed to withdraw south of the Danube Limes. Commodus left for Rome at the end of 180 AD, where he celebrated a triumph.[36]

Romanization of the barbarian population continued in the late Roman period (181-380 AD). Many Roman-style buildings with evidence of trade with the Roman Empire were built in what is now south-western Slovakia at Bratislava, Dúbravka, Cífer, Pác and Veľký Kýr.[37] Roman influence can be also seen in baths, coins, glass and amphorae dated to this period.[38] The Marcomanni converted to Christianity towards the end of the fourth century when Fritigil, their queen, obtained help from Ambrose, the formidable bishop of Milan (Italy), and also persuaded her husband to place himself and his people under Roman protection.[39]

Disintegration

In 373 AD, hostilities erupted between the Romans and the Quadi, who were outraged that Valentinian I was building fortifications in their territory. They complained and sent deputations that were ignored by Aequitius, the magister armorum per Illyricum. However, by that year the construction of these forts was behind schedule. Maximinus, now praetorian prefect of Gaul, arranged with Aequitius to promote his son Marcellianus and put him in charge of finishing the project. The protests of Quadian leaders continued to delay the project, and in a fit of frustration Marcellianus murdered the Quadian king Gabinius at a banquet ostensibly arranged for peaceful negotiations. This roused the Quadi to war. Valentinian did not receive news of these crises until late 374 AD. In the fall he crossed the Danube at Aquincum into Quadian and Marcomannic territory.[40]

After pillaging the lands of today's western Slovakia nearly without opposition, Valentinian retired to Savaria to winter quarters.[41] In the spring he decided to continue campaigning and moved from Savaria to Brigetio. Once he arrived on November 17, he received a deputation from the Quadi. In return for supplying fresh recruits to the Roman army, the Quadi were to be allowed to leave in peace. However, before the envoys left they were granted an audience with Valentinian. The envoys insisted that the conflict was caused by the building of Roman forts in their lands. Furthermore, they said individual bands of Quadi were not necessarily bound to the rule of the chiefs who had made treaties with the Romans, and thus might attack the Romans at any time. This attitude of the envoys so enraged Valentinian I that he suffered a stroke that ended his life.[42]

In 434 Attila devastated the area and started the mass migrations that destroyed the Western Roman Empire.[43] Later the area began to be occupied by Slav tribes. The first written source suggesting that Slavic tribes established themselves in what is now Slovakia is connected to the migration of the Germanic Heruli from the Middle Danube region towards Scandinavia in 512.[44] In this year, according to Procopius, they first passed "through the land of the Slavs", most probably along the river Morava.[14] A cluster of archaeological sites in the valleys of the rivers Morava, Váh and Hron also suggests that at the latest the earliest Slavic settlements appeared in the territory around 500 AD.[15] They are characterized by vessels similar to those of the "Mogiła" group of southern Poland and having analogies in the "Korchak" pottery of Ukraine.[16]

Archaeological remains

Laugaricio

The winter camp of Laugaricio (modern-day Trenčín) lies near the northernmost line of the Roman hinterlands, the limes Romanus. This was where the Legio II Adiutrix fought and prevailed in a decisive battle over the tribe of Quadi in 179 AD. Laugaricio is the most northern remains of the presence of Roman soldiers in central Europe.[45]

Soldiers of the Legio II Adiutrix carved the Roman inscription on the rock below today's castle. It reads: Victoriae Augustorum exercitus, qui Laugaricione sedit, mil(ites) l(egiones) II DCCCLV. (Maximi)anus leg(atus leg)ionis II Ad(iutricis) cur(avit) f(aciendum) (To the Victory of the army of the Augusti, stationed in Laugaricio, 855 legionaries of the II (dedicated this monument), the arrangements being undertaken by Maximian, legate of Legio II Adiutrix.)[46]

Gerulata

Gerulata was a Roman military camp from the second to fourth centuries. It is located near Rusovce, on the right side of the Danube to the south of Bratislava.[47] The name was probably taken from the Celtic name for the location, which seems to have been near a ford over the river. The fortified camp was established in the Flavian period, built by the X, XIV and XV Legions, and continued to be occupied and modified throughout the Roman period.[48]

The site has been subject to many years of archaeological research. Findings include inscribed stone votive altars and sepulchral monuments richly decorated with plant and figures. Many military artifacts have been discovered, as well as decorative jewelry, clasps and buckles. Jewels include gems, armlets, bracelets, pendants, rings, amulets. Coins include a complete sequence of Roman emperors apart from a short break in the first half of the third century. The findings also include everyday tools and implements – sickles, scissors, chisels, wrenches, clamps, fittings. The soldiers also left behind gambling chips and dice.[48]

The findings reflect the cosmopolitan nature of the Roman empire. Troops stationed here also campaigned on the lower Rhine and in Africa. Roman, Etruscan and Greek deities are represented, as well as symbols from the cults of Phrygia, Syria, Africa and elsewhere. There are also early traces of Christianity.[48]

Celemantia

The fortress of Celemantia is within the modern village of Iža on the left side of the Danube, downstream from Gerulata.[50] Brigetio (modern Szőny, Hungary) on the south bank of the Danube in Pannonia was a thriving urban center, as shown by the remains of temples, mineral spring spas and villas that contained elaborate mosaics, pottery and metalwork. Celementia was purely a military outpost, connected to Brigeto by a pontoon bridge that could be removed in wartime. Construction of the castellum of Celemantia started in 171 AD on the orders of Marcus Aurelius.[51] The fortress was burned down in 179 by the Marcomannic and Quadian tribes, but a stone fort was later built on the same site that lasted into Late Antiquity.[20]

Celemantia was a huge fortress. It was laid out as a square with sides about 172 metres (564 ft) long, with rounded corners. The walls were up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide and 5 metres (16 ft) high. The camp had 20 towers with reinforced walls and two towers guarding gates in the center of the sides of the square. The camp buildings included barracks, stables and warehouses constructed on standard designs. The main buildings were entirely built of stone, but most buildings had stone foundations with adobe walls and tile roofs. The camp also contained tanks, wells, cisterns and ovens. A major renovation was undertaken in the fourth century.[52]

At the end of the fourth century the camp was destroyed and was not rebuilt. The Germanic Quadi occupied the ruins for a while, but by the middle of the fifth century it had been abandoned. In modern times, the camp was used as a quarry to build the fortress and other buildings in nearby Komárno. Exploratory archaeological work was conducted in 1906-1909, with sporadic projects from then onwards. The layout and methods of construction have gradually been uncovered. Discoveries include coins and other metal objects, an ivory statuette of a comic actor, ceramic fragments, weapons, jewelry, tools and equipment. Stone sculptures show a diversity of religious beliefs.[52]

Other locations

- One of the first Roman military installations in the Middle Danube region is visible on the steep hill of Devín, where the Morava flows into the Danube. This may be a small fortress or fortified tower.[20] In the ruins of the Roman castle an iron cross was found in a tomb dating to the fourth century, the earliest relic of Christianity north of the Danube.[53]

- The small Roman forts in Závod and Suchohrad in the Morava river region indicate an attempt to penetrate toward northern Bohemia-Moravia and the Oder river, and perhaps into southern Poland.[54][55]

- A Roman fort from the period of the Marcomannic wars has been excavated in Stupava near Bratislava. Discoveries include documents, ceramics, jewelry, coins, fragments of glass vessels and economic tools.[56]

- The latest archaeological discoveries which have located new Roman enclosures in the surroundings of Brno, Czech Republic led to the conclusion that the advance of Roman troops from Carnumtum could have run further to the north-east, into the region of the Slovak-Polish border. Indeed, recent archaeological excavations and aerial surveys have shown further locations in northeast Moravia: three temporary Roman camps (possibly connected to the Laugaricio fort) situated in the foreland of the so-called Moravian Gate (Olomouc-Neředín, Pravčice, Osek) have been partly corroborated, the former two clearly by digging.[57]

See also

Notes

- Frontier of the Roman Empire in Slovakia Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Historia Augusta - Aurelius, pp. 24.5.

- Harmadyova, Rajtar & Schmidtova 2008.

- Roman army in the Czech Republic (in Czech)

- Map with Roman fortifications (in german)

- Krško 2003.

- Roman marching camps in Bohemia-Moravia

- Marching or temporary camps of Roman troops in western Slovakia and eastern Moravia

- Moravian Gate Map

- Stupava (in Slovak)

- Terra sigillata

- Mócsy 1974, p. 345; Todd 2004, p. 119.

- Heather 2010, pp. 407–408; Barford 2001.

- Heather 2010, p. 408.

- Heather 2010, pp. 409–410; Barford 2001, p. 54.

- Barford 2001, pp. 53–54.

- Eck 2003, pp. 94.

- The Roman army in the CR.

- Dio 222, pp. LV.

- Frontier Regions - Slovakia.

- Tacitus.

- Pitts 1989, pp. 46.

- Dio 222, pp. LXXII.1 ff.

- McLynn 2009, pp. 327–328.

- McLynn 2009, pp. 357ff.

- Birley 2000, pp. 171–174.

- Dio 222, pp. LXXII.8-10.

- Der Romische Limes.

- Dio 222, pp. LXXII.13-14.

- Birley 2000, pp. 178.

- McLynn 2009, pp. 381ff.

- Beckmann 2002.

- Birley 2000, pp. 206.

- Birley 2000, pp. 207.

- Birley 2000, pp. 209–210.

- Historia Augusta - Commodus.

- Kuzmová.

- Komoróczy & Varsík.

- Fritigil.

- Marcellinus 391, pp. XXX.5.13.

- Marcellinus 391, pp. XXX.5.14.

- Marcellinus 391, pp. XXX.6.

- Howarth 1994, pp. 36ff.

- Heather 2010, pp. 407–408; Barford 2001, p. 53.

- Boundary Productions.

- Pelikán 1960, pp. 218.

- Müller & Kelcey 2011, pp. 83.

- Ancient Gerulata Rusovce.

- Roman Castle Celemantia...

- Erdkamp 2008, pp. 410.

- Schwegler 2008, pp. 24.

- Celemantia - Iža.

- Castle of the Week.

- Hanel & Cerdan 2009, pp. 893.

- Marching or temporary camps...

- Stupava.

- Roman marching or temporary camps.

Sources

- "Ancient Gerulata Rusovce" (in Slovak). Bratislava City Museum. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. Cornell. ISBN 0-8014-3977-9.

- Beckmann, Martin (2002). "The 'Columnae Coc(h)lides' of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius". Phoenix. Classical Association of Canada. 56 (3/4): 348–357. doi:10.2307/1192605. JSTOR 1192605.

- Birley, Anthony (2000). Marcus Aurelius. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17125-3.

- Boundary Productions. "The Danube Limes in Slovakia". Limes World Heritage Site. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- "Castle of the Week 108 - Devín Castle, Slovak Republic". Stronghold Heaven. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- "Celemantia - Iža (SK)". MAGYAR LIMES SZÖVETSÉG. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- "Der Romische Limes in der Slowakei (The Roman Limes in Slovakia)" (in German). Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- Dio, Cassius (222). Roman History.

- Eck, Werner (2003). The Age of Augustus. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22957-5.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2008). A companion to the Roman army. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8.

- "Fritigil, markomannische Königin". Encyclopedia of Austria. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- "Frontier Regions - Slovakia". romanfrontiers.org. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- Harmadyova, Katarina; Rajtar, Jan; Schmidtova, Jaroslava (2008). "Frontiers of the Roman Empire - Slovakia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- Hanel, Norbert; Cerdan, Angel Morillo (2009). Limes XX: studies on the Roman frontier of Gladius Schedules. CSIC. ISBN 978-84-00-08854-5.

- Howarth, Patrick (1994). Attila, King of the Huns: man and myth. Barnes & Noble Publishing. ISBN 0-7607-0033-8.

- Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-973560-0.

- anon (395). Historia Augusta: Marcus Aurelius.

- anon (395). Historia Augusta: Commodus.

- Komoróczy, Balázs; Varsík, Vladimír. "Provincial Roman pottery in the region north of the Middle Danube". Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- Krško, Jaromír (June 2003). "Názvy potokov v Banskej Bystrici a okolí". Bystrický Permon. 1 (2): 8.

- Kuzmová, Klára. "Terra sigillata north of the Norican-Pannonian Limes". Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- Marcellinus, Ammianus (391). Res Gestae.

- "Marching or temporary camps of Roman troops north to the Middle Danube". Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- McLynn, Frank (2009). Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor. London: Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-224-07292-2.

- Mócsy, András (1974). Pannonia and Upper Moesia. History of the provinces of the Roman Empire. Vol. 4. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7100-7714-1.

- Müller, Norbert; Kelcey, John G. (2011). Plants and Habitats of European Cities. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-89683-0.

- Pelikán, Oldřich (1960). Slovensko a Rímske impérium. Slovenské vydavatel̕stvo krásnej literatúry.

- Pitts, Lynn (1989). "Relations between Rome and the German 'Kings' on the Middle Danube in the First to Fourth Centuries A.D" (PDF). The Journal of Roman Studies. 79: 45–58. doi:10.2307/301180. JSTOR 301180.

- "Roman Castle Celemantia of Iža Virtual Tour, National Cultural Heritage". Petit Press. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- "Roman marching or temporary camps north to the Danube and the main directions of Roman thrusts to the north". Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- Schwegler, Brian Alexander (2008). Confronting the devil: Europe, nationalism, and municipal governance in Slovakia. ISBN 978-0-549-45838-8.

- "Stupava History" (in Czech). Stupava City. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- Tacitus. Germany Book 1.40.

- "The Roman army in the CR" (in Czech). Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- Todd, Malcolm (19 November 2004). The Early Germans. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-1714-2.

Further reading

- Kandler, M. Gli accampamenti militari di Carnuntum (in "Roma sul Danubio") Roma, 2002.

- Kerr, W.G. A Chronological Study of the Marcomannic Wars of Marcus Aurelius. Princeton University ed. Princeton, 1995

- Komoróczy, K otázce existence římského vojenského tábora na počátku 1. st. po Kr. u Mušova (katastr Pasohlávky, Jihomoravský kraj). Kritické poznámky k pohledu římsko provinciální archeologie, in E.Droberjar, - M.Lutovský, Archeologie barbarů, Praha, 2006, pp. 155–205.

- Kovács, Peter. Marcus Aurelius' Rain Miracle and the Marcomannic Wars. Brill Academic Publishers. Leiden, 2009. ISBN 978-90-04-16639-4

- G. Langmann. Die Markomannenkriege 166/167 bis 180. Militärhistor. Schriftenreihe 43. Wien, 1981.

- Ritterling, E. Legio X Gemina. RE XII, 1925, col.1683-1684.