May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese cultural and anti-imperialist political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chinese government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles decision to allow Japan to retain territories in Shandong that had been surrendered by Germany after the Siege of Tsingtao in 1914. The demonstrations sparked nation-wide protests and spurred an upsurge in Chinese nationalism, a shift towards political mobilization away from cultural activities, and a move towards a populist base, away from traditional intellectual and political elites.

| May Fourth Movement 五四運動 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

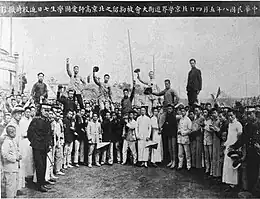

.jpg.webp) Around 3,000 students from 13 universities in Beijing gathered in Tiananmen Square | |||

| Date | 4 May 1919 | ||

| Location | |||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| May Fourth Movement | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 五四運動 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 五四运动 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | 5-4 Movement | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

The May Fourth demonstrations marked a turning point in a broader anti-traditional New Culture Movement (1915–1921) that sought to replace traditional Confucian values and was itself a continuation of late Qing reforms. Yet even after 1919, these educated "new youths" still defined their role with a traditional model in which the educated elite took responsibility for both cultural and political affairs.[1] They opposed traditional culture but looked abroad for cosmopolitan inspiration in the name of nationalism and were an overwhelmingly urban movement that espoused populism in an overwhelmingly rural country. Many political and social leaders of the next five decades emerged at this time, including those of the Chinese Communist Party.[2]

Background

"The atmosphere and political mood that emerged around 1919," in the words of Oxford University historian Rana Mitter, "are at the center of a set of ideas that has shaped China's momentous twentieth century."[3] The Qing dynasty had disintegrated in 1911, marking the end of thousands of years of imperial rule in China, and theoretically ushered a new era in which political power rested nominally with the people. After the death of President Yuan Shikai in 1916, China became a fragmented nation dominated by regional leaders more concerned with political power and rival regional armies. The government in Beijing focused on suppressing internal dissent and could do little to counter foreign influence and control.[3] Chinese Premier Duan Qirui's signing of the secret Sino-Japanese Joint Defence Agreement in 1918 enraged the Chinese public when it was leaked to the press, and sparked a student protest movement that laid the groundwork for the May Fourth Movement.[4] The March 1st Movement in Korea in 1919, the Russian Revolution of 1917, continued defeats by foreign powers and the presence of spheres of influence further inflamed Chinese nationalism among the emerging middle class and cultural leaders.[3]

Leaders of the New Culture Movement believed that traditional Confucian values were responsible for the political weakness of the nation.[5][6] Chinese nationalists called for a rejection of traditional values and the adoption of Western ideals of "Mr. Science" (賽先生; 赛先生; sài xiānsheng) and "Mr. Democracy" (德先生; dé xiānsheng) in place of "Mr. Confucius" in order to strengthen the new nation.[7] These iconoclastic and anti-traditional views and programs have shaped China's politics and culture through to the present day.[8]

Shandong Problem

China had entered World War I on the side of the Allied Triple Entente in 1917. Although that year, 140,000 Chinese laborers were sent to the Western Front as a part of the Chinese Labor Corps,[9] the Versailles Treaty of April 1919 awarded rights to the German territories in Shandong Province to Japan. The representatives of the Chinese government put forth the following requests:

- Abolition of all privileges of foreign powers in China, such as extraterritoriality

- Cancelling of the "Twenty-One Demands" with the Japanese government

- Return to China of the territory and rights of Shandong, which Japan had taken from Germany during World War I.

The Western allies dominated the meeting at Versailles, and paid little heed to Chinese demands. The European delegations, led by French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, were primarily interested in punishing Germany. Although the American delegation promoted Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points and the ideals of self-determination, they were unable to advance these ideals in the face of stubborn resistance by David Lloyd George and Clemenceau. American advocacy of self-determination at the League of Nations was attractive to Chinese intellectuals, but their failure to follow through was seen as a betrayal. This diplomatic failure at the Paris Peace Conference created what became known as the "Shandong Problem".[10][11]

Participants

On May 4, 1919, the May Fourth Movement, as a student patriotic movement, was initiated by a group of Chinese students protesting the contents of the Paris Peace Conference. Under the pressure of the May Fourth Movement, the Chinese delegation refused to sign the Versailles Treaty.

The original participants of the May Fourth Movement were students in Paris and some in Beijing. They joined forces to strike or took to the streets to strike crudely to express their dissatisfaction with the government. Later, some advanced students in Shanghai and Guangzhou joined the protest movement, gradually forming a wave of mass student strikes across China. Until June 1919, the Beijing government carried out the "June 3" arrests, arresting nearly 1,000 students one after another, but this did not suppress the patriotic student movement but angered the whole Chinese people, leading to a greater revolutionary storm. Shanghai workers went on strike, and businessmen went on strike to support students' patriotic movement across the country. The Chinese working class entered the political arena through the May Fourth Movement.

With the emergence of working-class support, the May Fourth Movement developed to a new stage. The center of the movement shifted from Beijing to Shanghai, and the working class replaced students as the main force of the movement. The Shanghai working class staged a strike of an unprecedented scale. The growing scale of the national strike and the increasing number of its participants led to a paralysis of the country's economic life and posed a serious threat to the government in Beijing. The working class took the place of the students to stand up and resist. The support for this movement throughout the country reflected the enthusiasm for nationalism and national rejuvenation, which was also the foundation for the development and expansion of the May Fourth Movement. Benjamin I. Schwartz added, "Nationalism which was, of course, a dominant passion of the May Fourth experience was not so much a separate ideology as a common disposition."[12]

Days of protest

On the morning of 4 May 1919, student representatives from thirteen different local universities met in Beijing and drafted five resolutions:

- To oppose the granting of Shandong to the Japanese under former German concessions.

- To draw and increase awareness of China's precarious position to the masses in China.

- To recommend a large-scale gathering in Beijing.

- To promote the creation of a Beijing student union.

- To hold a demonstration that afternoon in protest to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

On the afternoon of May 4 over 4,000 students of Yenching University, Peking University and other schools marched from many points to gather in front of Tiananmen. They shouted such slogans as "struggle for the sovereignty externally, get rid of the national traitors at home", "do away with the Twenty-One Demands", and "don't sign the Versailles Treaty".

They voiced their anger at the Allied betrayal of China, denounced the government's spineless inability to protect Chinese interests, and called for a boycott of Japanese products. Demonstrators insisted on the resignation of three Chinese officials they accused of being collaborators with the Japanese. After burning the residences of these officials and beating some of their servants, student protesters were arrested, jailed, and severely beaten.[13]

The next day, students in Beijing as a whole went on strike and in the larger cities across China, students, patriotic merchants, and workers joined protests. The demonstrators skillfully appealed to the newspapers and sent representatives to carry the word across the country. From early June, workers and businessmen in Shanghai also went on strike as the center of the movement shifted from Beijing to Shanghai. Chancellors from thirteen universities arranged for the release of student prisoners, and Cai Yuanpei, the principal of Peking University resigned in protest.

Newspapers, magazines, citizen societies, and chambers of commerce offered support for the students. Merchants threatened to withhold tax payments if China's government remained obstinate.[14] In Shanghai, a general strike of merchants and workers nearly devastated the entire Chinese economy.[13] Under intense public pressure, the Beijing government released the arrested students and dismissed Cao Rulin, Zhang Zongxiang and Lu Zongyu that had been accused of being collaborators with the Japanese. Chinese representatives in Paris refused to sign the Versailles Treaty: the May Fourth Movement won an initial victory which was primarily symbolic, since Japan for the moment retained control of the Shandong Peninsula and the islands in the Pacific. Even the partial success of the movement exhibited the ability of China's social classes across the country to successfully collaborate given proper motivation and leadership.[13]

Historical significance

| New Culture Movement |

|---|

|

|

Scholars rank the New Culture and May Fourth Movements as significant turning points, as David Der-wei Wang said, "it was the turning point in China's search for literary modernity",[15] along with the abolition of the civil service system in 1905 and the overthrow of the monarchy in 1911. The challenge to traditional Chinese values, however, was also met with strong opposition, especially from the Nationalist Party. From their perspective, the movement destroyed the positive elements of Chinese tradition and placed a heavy emphasis on direct political actions and radical attitudes, characteristics associated with the emerging Chinese Communist Party (CCP). On the other hand, the CCP, whose two founders, Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu, were leaders of the movement, viewed it more favorably, although remaining suspicious of the early phase which emphasized the role of enlightened intellectuals, not revolution.[16] In its broader sense, the May Fourth Movement led to the establishment of radical intellectuals who went on to mobilize peasants and workers into the CCP and gain the organizational strength that would solidify the success of the Chinese Communist Revolution.[14]

During the May 4th Movement, the group of intellectuals with communist ideas grew steadily, such as Chen Tanqiu, Zhou Enlai, Chen Duxiu, and others, who gradually appreciated Marxism's power. This promoted the sinicization of Marxism and provided a basis for the birth of the CCP and socialism with Chinese characteristics.[17]

The legacy of the May Fourth Movement is embraced both by the Communist Party and its critics, who express different understandings of the movement and its importance.[18]: 24

Birth of Chinese communism

| Part of a series on the |

| Chinese Communist Revolution |

|---|

Proclamation of the People's Republic of China |

|

|

For many years, the orthodox view in the People's Republic of China was that after the demonstrations of 1919 and their subsequent suppression, the discussion of possible policy changes became more and more politically realistic. Influential leaders such as Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao shifted to the left and became founders of the CCP in 1921, while other intellectuals became more sympathetic.[19] Originally voluntarist or nihilist figures like Li Shicen and Zhu Qianzhi made similar turns to the left as the 1920s saw China become increasingly turbulent.[20]

In 1939, CCP senior leader Mao Zedong claimed that the May Fourth Movement was a stage leading toward the fulfillment of the Chinese Communist Revolution:

The May Fourth Movement twenty years ago marked a new stage in China's bourgeois-democratic revolution against imperialism and feudalism. The cultural reform movement which grew out of the May Fourth Movement was only one of the manifestations of this revolution. With the growth and development of new social forces in that period, a powerful camp made its appearance in the bourgeois-democratic revolution, a camp consisting of the working class, the student masses and the new national bourgeoisie. Around the time of the May Fourth Movement, hundreds of thousands of students courageously took their place in the van. In these respects the May Fourth Movement went a step beyond the Revolution of 1911.[21]

Paul French argues that the only victor of the Treaty of Versailles in China was communism, as rising public anger led directly to the formation of the CCP. The Treaty also led to Japan pursuing its conquests with greater boldness, which Wellington Koo had predicted in 1919 would lead to the outbreak of war between China and Japan.[22]

Western-style liberal democracy had previously had a degree of traction amongst Chinese intellectuals. Still, after the Versailles Treaty (which was viewed as a betrayal of China's interests), it lost much of its attractiveness. Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, despite being rooted in moralism, were also seen as Western-centric and hypocritical.[20]

Many Chinese intellectuals believed that the United States had done little to convince the other nations to adhere to the Fourteen Points and observed that the United States had declined to join the League of Nations. As a result, they turned away from the Western liberal democratic model. With victory of the Russian October Revolution in 1917, Marxism began to take hold in Chinese intellectual thought, particularly among those already on the Left. Chinese intellectuals such as Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao began serious study of Marxist doctrine.[23]

Cultural

The May Fourth Movement focused on opposing Confucian culture and promoting a new culture. As a continuation of the New Culture movement, the May Fourth Movement greatly influenced the cultural field. The slogans of "democracy" and "science" advocated in the New Culture Movement were designed to attack the old culture and promote the new culture. This purpose can be summed up in a sentence from David Wang: "It was the turning point in China's search for literary modernity."[15] As historian Wang Gungwu notes, the May Fourth Movement became subsequently identified as the predecessor and inspiration for the later Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.[24]

Participants at the time, such as Hu Shih, referred to this era as the Chinese Renaissance because there was an intense focus on science and experimentation.[25] In Chinese literature, the May Fourth Movement is regarded as the watershed after which the modern Chinese literature began and the use of the vernacular language (baihua) gained currency over and eventually replaced the use of Literary Chinese in literary works.[26] Intellectuals were driven toward expressing themselves using the spoken tongue under the slogan 我手寫我口 ('my hand writes [what] my mouth [speaks]'), although the change was actually gradual: Hu Shih had already argued for the use of the modern vernacular language in literature in his 1917 essay "Preliminary discussion on literary reform" (文學改良芻議).[27]

The first vernacular Chinese fiction was the female author Chen Hengzhe's short story One Day (Chinese: 一日), published 1917 in an overseas student quarterly (Chinese:《留美学生季报》). This was a year before the publication of Lu Xun's Diary of a Madman and The True Story of Ah Q (not published until 1921), which has often been incorrectly credited as the first vernacular Chinese fiction.[27][28]

More ordinary people also began to try to get in touch with new cultures and learn from foreign cultures. Joseph Chen said: "This intellectual ferment had already had an effect in altering the outlook of China's new youth.".[29] After the May Fourth Movement, the Chinese modern female literature developed a literature with modern humanistic spirit, taking women as the subject of experience, thinking, aesthetics, and speech.[30]

Instead of the formerly euphemistic language for sex, May Fourth reformers used the broader, more explicit term, xing.[31]: 21

In honor of the May Fourth Movement, May 4 is now celebrated as Youth Day in mainland China and as Literary Day in Taiwan.

Economic

During the movement, anger against Japan erupted because the Paris peace Treaty gave it the right to occupy the Shandong Peninsula. Many elements of society and joined students to publicize the boycott of Japanese products. The wave of a boycotts led to hopes that when Japanese products were suppressed, China's national industry would develop and promote the rapid development of China's national economy.

Criticism and resistance

Although the movement was highly influential, many of the intellectuals at the time opposed the anti-traditional message and many political figures ignored it. "this limited May Fourth individualist enlightenment did not lead the individual against the collective of the nation-state, as full-scale, modern Western individualism would potentially do.".[32]

Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek, as a nationalist and Confucianist, was against the iconoclasm of the May Fourth Movement. As an anti-imperialist, he was skeptical of Western ideas and literature. He criticized these May Fourth intellectuals for corrupting the morals of youth.[33] When the Nationalist party came to power under Chiang's rule, it carried out the opposite agenda. The New Life Movement promoted Confucianism, and the Kuomintang purged China's education system of western ideas, introducing Confucianism into the curriculum. Textbooks, exams, degrees, and educational instructors were all controlled by the state, as were all universities.[34]

Some conservative philosophers and intellectuals opposed any change, but many more accepted or welcomed the challenge from the West but wanted to base new systems on Chinese values, not imported ones. These figures included Liang Shuming, Liu Shipei, Tao Xisheng, Xiong Shili, Zhang Binglin and Lu Xun's brother, Zhou Zuoren.[35] In later years, others developed critiques, including figures as diverse as Lin Yutang, Qian Mu, Xu Fuguan, and Yu Yingshi. Li Changzhi believed that the May Fourth Movement copied foreign culture and lost the essence of its own culture. (Ta Kung Pao, 1942). This is consistent with what Vera Schwarcz has said: "Critically-minded intellectuals were accused of eroding national self-confidence, or more simply, of not being Chinese enough."[1]

Chinese Muslims ignored the May Fourth movement by continuing to teach Classical Chinese and literature with the Qur'an and Arabic along with officially mandated contemporary subjects at the "Normal Islamic School of Wanxian".[36] Ha Decheng did a Classical Chinese translation of the Quran.[37] Arabic, vernacular Chinese, Classical Chinese and the Qur'an were taught in Ningxia Islamic schools funded by Muslim General Ma Fuxiang.[38]

Neotraditionalism vs. Western thought

Although the May Fourth Movement did find partial success in removing traditional Chinese culture,[39] there were still proponents who steadfastly argued that China's traditions and values should be the fundamental foundations of the nation. From these opponents of Western civilization derived three neotraditional schools of thought: national essence, national character, and modern relevance of Confucianism. Each school of thought denounced the western values of individualism, materialism and utilitarianism as inadequate avenues for the development of China. Each school held to specific objectives. The "national essence" school sought to discover aspects of traditional culture that could potentially serve the national development of China. Such traditional aspects consisted of various philosophical and religious practices that emerged parallel with Confucianism. Most particularly, China imported Buddhism, a religion from their neighboring countries, India and Nepal. Under the "national character" school, advocates promoted the traditional family system, the primary target of the May Fourth Movement. In this school, reformers viewed Westerners as shells without morals. Finally, the modern relevance of Confucianism was centered on the notion that Confucian values were better than Western ones. In response to western culture's primary concentration on rational analysis, China's neo-traditionalists argued that this was misguided, especially in the practical, changing milieu of the world. Most importantly, these three neo-traditionalist thoughts did not consider the individual, which was the main theme of the May Fourth Movement.[16]

See also

- "Diary of a Madman" by Lu Xun

- History of the Republic of China

- History of Beijing

- Cultural Revolution

- 1976 Tiananmen Incident (April Fifth Movement of 1976)

- Qiu Jin

- March 1st Movement in Korea

- East-West Cultural Debate

References

Citations

- Schwarcz 1986, pp. 9–11.

- Hayford (2009), p. 569.

- Mitter (2004), p. 12.

- Sugano, Tadashi (1986). "日中軍事協定の廃棄について" [On the scrapping of the Sino-Japanese military agreements] (PDF). Nara Journal of History (in Japanese). 4 (12): 34.

- Joseph T. Chen, The May Fourth Movement in Shanghai; the Making of a Social Movement in Modern China (Leiden,: Brill, 1971)

- Leo Ou-fan Lee, Voices from the Iron House: A Study of Lu Xun (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), pp 53-77; 76-78.

- Jonathan D. Spence. The Gate of Heavenly Peace: The Chinese and Their Revolution, 1895-1980. (New York: Viking Press, 1981), pp. 117-123 ff.

- The Cambridge History of Chinese". John King Fairbank, Denis Crispin Twitchett, p.451

- Guoqi Xu. Strangers on the Western Front: Chinese Workers in the Great War. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2011. ISBN 9780674049994), pp. 1-9, and passim.

- "Shandong question - Chinese history". Encyclopedia Britannica. July 20, 1998. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- Guoqi, Xu (November 24, 2016). "China and Japan at Paris". Asia and the Great War. Oxford University Press. pp. 153–184. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199658190.003.0007. ISBN 978-0-19-965819-0.

- Schwartz, Benjamin I. (1973). Reflections on the May Fourth Movement. Harvard University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-68417-175-0.

- Wasserstrom, Jeffrey N. "Chinese Students and Anti-Japanese Protests, Past and Present". World Policy Journal. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- Hao, Zhidong. "May 4th and June 4th Compared: A Sociological Study of Chinese Social Movements". Journal of Contemporary China. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- Wang 2017, p. 2.

- Schoppa, R.Keith. Revolution and Its Past: Identities and Change in Modern Chinese History. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 177–179.

- Chan, Adrian (2003). Chinese Marxism. Continuum Publishing. ISBN 978-0826473073.

- Šebok, Filip (2023). "Historical Legacy". In Kironska, Kristina; Turscanyi, Richard Q. (eds.). Contemporary China: a New Superpower?. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-03-239508-1.

- Patrick Fuliang Shan, “Li Dazhao and the Chinese Embracement of Communism,” in Shiping Hua (ed.), Chinese Ideology, Routledge, 2022, 94-110.

- Lin, Yu-Kai; Mair, Victor H (2020). Remembering May Fourth: The Movement and its Centennial Legacy. Brill. pp. 58 & 114. ISBN 978-90-04-42488-3.

- The May Fourth Movement (May 1939)

- French, Paul (2016). Betrayal in Paris: How the Treaty of Versailles led to China's Long Revolution. Penguin. pp. 74–78.

- Patrick Fuliang Shan, “Assessing Li Dazhao’s Role in the New Cultural Movement,” in A Century of Student Movements in China: The Mountain Movers, 1919-2019, Rowman Littlefield and Lexington Books, 2020, pp.3-22.

- Gungwu, Wang (1979–1980). "May Fourth and the GPCR: The Cultural Revolution Remedy". Pacific Affairs. 52 (4): 674–690. doi:10.2307/2757067.

- Hu Shih, The Chinese Renaissance: The Haskell Lectures, 1933. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934).

- Wang 2017, pp. 15–16.

- Hockx 2017, pp. 265–270.

- Wang 2017, pp. 254–259.

- Chen, Joseph T. (1971). The May Fourth Movement in Shanghai: The Making of a Social Movement in Modern China. BRILL. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-90-04-02567-7.

- Wang 2017, p. 16.

- Rodriguez, Sarah Mellors (2023). Reproductive realities in modern China : birth control and abortion, 1911-2021. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-02733-5. OCLC 1366057905.

- Chen, Xiaoming (June 5, 2008). From the May Fourth Movement to Communist Revolution. SUNY Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7914-7986-5.

- Joseph T. Chen (1971). The May fourth movement in Shanghai: the making of a social movement in modern China. Brill Archive. p. 13. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Werner Draguhn, David S. G. Goodman (2002). China's communist revolutions: fifty years of the People's Republic of China. Psychology Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-7007-1630-0. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- Charlotte Furth, "Culture and Politics in Modern Chinese Conservatism," in Charlotte Furth, ed., The Limits of Change: Essays on Conservative Alternatives in Republican China. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, Harvard East Asian Series 84, 1976). ISBN 0674534239.

- Dudoignon, Stephane A.; Hisao, Komatsu; Yasushi, Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the Modern Islamic World: Transmission, Transformation and Communication. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-20597-4. p. 251.

- Dudoignon, Hisao & Yasushi 2006, p. 253.

- Dudoignon, Hisao & Yasushi 2006, p. 256.

- Chow 2013, p. 173.

Sources and further reading

- Chen, Joseph T. "The May Fourth Movement Redefined." Modern Asian Studies 4.1 (1970): 63-81 online.

- Chow, Tse-tsung (2013) [1960]. The May Fourth Movement: Intellectual Revolution in Modern China. Harvard, Ma: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-28340-4.

- Hao, Zhidong, "May 4th and June 4th Compared: A Sociological Study of Chinese Social Movements." Journal of Contemporary China 6.14 (1997): 79–99.

- Hockx, Michel (2017). "The Big Misnomer: ʽʽMay Forth Literatureʻʻ". In Wang, David Der-wei (ed.). A New Literary History of Modern China. Harvard, Ma: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97887-4.

- Lee, Haiyan, "Tears that Crumbled the Great Wall: The Archaeology of Feeling in the May Fourth Folklore Movement." Journal of Asian Studies 64.1 (2005): 35–65.

- Hayford, Charles (2009). "May Fourth Movement". In Pong, David (ed.). Encyclopedia of Modern China. Vol. II. Detroit, Mi: Scribner's. pp. 565–69.

- Ping, Liu, "The Left Wing Drama Movement in China and Its Relationship to Japan." Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 14.2 (2006): 449–466.

- Mitter, Rana (2004). A Bitter Revolution: China's Struggle with the Modern World. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192803417.

- Schoppa, R. Keith (2006). "Constructing a New Cultural Identity: The May Fourth Movement." In Revolution and Its Past: Identities and Change in Modern Chinese History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 162–180.

- Schwarcz, Vera (1986). The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919. Berkeley, Ca: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06837-7.

- Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China. ISBN 0-393-30780-8 New York: Norton, 1999.

- Wang, David Der-wei, ed. (2017). A New Literary History of Modern China. Harvard, Ma: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97887-4.

- Wang, Q. Edward. "The May Fourth Movement: A centennial anniversary—Editor's introduction" Chinese Studies in History (2019), Vol. 52 Issue 3/4, p183-187.

- Wang, Q. Edward. "The Chinese Historiography of the May Fourth Movement, 1990s to the Present," Twentieth Century China, 44#2 (May 2019), 138–49.

- Wang, Q. Edward. “May Fourth Movement,” Oxford Bibliographies online a survey of international scholarship

- Wasserstrom, Jeffrey N., "Chinese Students and Anti-Japanese Protests, Past and Present" World Policy Journal 22.2 (2005): 59–65.

- Widmer, Ellen, and David Wang ed. From May fourth to June fourth: fiction and film in twentieth-century China (1993) online

- Youngseo, Baik. "1919 in dynamic East Asia: March First and May Fourth as a starting point for revolution." Chinese Studies in History (2019), Vol. 52 Issue 3/4, p277-291; March 1 was a similar event in Korea.

- Zarrow, Peter, "Intellectuals, the Republic, and a new culture", in Zarrow, China in war and revolution, 1895-1949 (Routledge, 2005) pp. 133–143.

- Zarrow, Peter, "Politics and culture in the May Fourth Movement", in Peter Zarrow, China in war and revolution, 1895-1949 (Routledge, 2005) pp. 149–169.

External links

- Columbia University, China: A Teaching Workbook — documents on May Fourth Movement

- May 4th 1919 Monument in Beijing — photos, directions, + background.

- Chinese Posters.net: "May Fourth Movement (1919)"

- Chinese Posters.net: "Propaganda, Politics, History, Art" (Amsterdam University) — mostly post 1949 posters, and commentary.