Chola Empire

The Chola Empire, often referred to as the Imperial Cholas,[1] was a medieval Indian thalassocratic empire established by Pottapi branch of the Chola dynasty that rose to prominence during the middle of the 9th century CE and successfully united southern India under their rule.

Chola Empire | |

|---|---|

| 848–1279 | |

._Chola%252C_conqueror_of_the_Gangas_in_Tamil%252C_seated_tiger_with_two_fish.jpg.webp) Imperial coin of Emperor Rajaraja I (985–1014). Uncertain Tamilnadu mint. Legend "Chola, conqueror of the Gangas" in Tamil, seated tiger with two fish.

| |

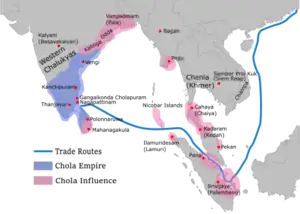

Map showing the greatest extent of the Chola empire c. 1030 under Rajendra I: territories are shown in blue, subordinates and areas of influence are shown in pink. | |

| Capital | Pazhaiyaarai, Thanjavur, Gangaikonda Cholapuram |

| Official languages |

|

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Emperor | |

• 848–871 | Vijayalaya Chola (first) |

• 1246-1279 | Rajendra III (last) |

| Historical era | Middle Ages |

• Established | 848 |

• Empire at its greatest extent | 1030 |

• Disestablished | 1279 |

The power and the prestige the Cholas had among political powers in South, Southeast, and East Asia at its peak is evident through their expeditions to the Ganges, naval raids on cities of the Srivijaya Empire based on the island of Sumatra, and their repeated embassies to China.[2] The Chola fleet represented the zenith of ancient Indian maritime capacity. Around 1070 the Cholas began to lose almost all of their overseas territories, but the later Cholas (1070–1279) continued to rule portions of southern India. The Chola empire went into decline at the beginning of the 13th century with the rise of the Pandyan dynasty, which ultimately caused their downfall.[3]

The Cholas established a centralized form of government and a disciplined bureaucracy. Moreover, their patronage of Tamil literature and their zeal for building temples has resulted in some of the greatest works of Tamil literature and architecture.[4] The Chola kings were avid builders and envisioned the temples in their kingdoms not only as places of worship but also as centres of economic activity.[5][6] A UNESCO world heritage site, the Brihadisvara temple at Thanjavur, commissioned by the Rajaraja in 1010, is a prime example for Chola architecture. They were also well known for their patronage to art. The development of the specific sculpturing technique used in the 'Chola bronzes', exquisite bronze sculptures of Hindu deities built in a lost wax process was pioneered in their time. The Chola tradition of art spread and influenced the architecture and art of Southeast Asia.[7][8]

Founding

Vijayalaya, the successor of Srikantha Chola was the founder of the Chola empire in 848 CE.[9] Vijayalaya belonging to Pottapi Chola family, a Telugu Chola branch which claimed descent from ancient Tamil king Karikala Chola[10]and possibly a feudatory of the Pallava dynasty, took an opportunity arising out of a conflict between the Pandya empire and Pallava empire in c. 850, captured Thanjavur from Muttarayar, and established the imperial line of the medieval Chola Dynasty.[11][12] Thanjavur became the capital of the Imperial Chola empire.[13]

Under Aditya I, the Pallava dynasty and defeated the Pandyan dynasty of Madurai in 885, occupied large parts of the Kannada country, and had marital ties with the Western Ganga dynasty. In 925, his son Parantaka I conquered Sri Lanka (known as Ilangai). Parantaka I also defeated the Rashtrakuta dynasty under Krishna II in the battle of Vallala.[14] Later Parantaka I was defeated by Rashtrakutas under Krishna III and Cholas' heir apparent Rajaditya Chola was killed in the Battle of Takkolam. Cholas lost Tondaimandalam region to Rashtrakutas in that battle.

The Chola power recovered under the reign of Parantaka II. The Chola army under the command of the crown prince Aditha Karikalan defeated the Pandyas and expanded the kingdom up to Tondaimandalam. Aditha Karikalan was assassinated in a political plot. After Parantaka II, Uttama Chola became the Chola emperor followed by Raja Raja Chola I, the greatest Chola monarch.

Imperial Era

Under Rajaraja I and Rajendra I, the Empire would reach it's impereal state.[15] At its peak, the Chola empire stretched from the northern parts of Sri Lanka in the south to the Godavari–Krishna river basin in the north, up to the Konkan coast in Bhatkal, the entire Malabar Coast (the Chea country) in addition to Lakshadweep, and Maldives. Rajaraja Chola I was a ruler with inexhaustible energy, and he applied himself to the task of governance with the same zeal that he had shown in waging wars. He integrated his empire into a tight administrative grid under royal control, and at the same time strengthened local self-government. Therefore, he conducted a land survey in 1000 CE to effectively marshall the resources of his empire.[16] He also built the Brihadeeswarar Temple in 1010.[17]

Rajendra conquered Odisha and his armies continued to march further north and defeated the forces of the Pala dynasty of Bengal and reached the Ganges river in north India.[18] Rajendra built a new capital called Gangaikonda Cholapuram to celebrate his victories in northern India.[19] Rajendra I successfully invaded the Srivijaya kingdom in Southeast Asia which led to the decline of the empire there.[20] This expedition had such a great impression to the Malay people of the medieval period that his name was mentioned in the corrupted form as Raja Chulan in the medieval Malay chronicle Sejarah Melayu.[21][22][23] He also completed the conquest of the Rajarata kingdom of Sri Lanka and took the Sinhala king Mahinda V as a prisoner, in addition to his conquests of Rattapadi (territories of the Rashtrakutas, Chalukya country, Talakkad, and Kolar, where the Kolaramma temple still has his portrait statue) in Kannada country.[24] Rajendra's territories included the area falling on the Ganges–Hooghly–Damodar basin,[25] as well as Rajarata of Sri Lanka and Maldives.[11] The kingdoms along the east coast of India up to the river Ganges acknowledged Chola suzerainty.[26] Three diplomatic missions were sent to China in 1016, 1033, and 1077.[11]

permanent territorial gain and the kingdom was returned to the Srivijaya king for recognition of Chola superiority and the payment of periodic tributes.

Chola–Chalukya Wars

The history of the Cholas from the period of Rajaraja was tinged with a series of conflicts with the Western Chalukyas. The Old Chalukya dynasty had split into two sibling dynasties of the Western and Eastern Chalukyas. Rajaraja's daughter Kundavai was married to the Eastern Chalukya prince Vimaladitya, who ruled from Vengi. The Western Chalukyas felt that the Vengi kingdom was under their natural sphere of influence. Cholas inflicted several defeats on the Western Chalukyas. For the most part, the frontier remained at the Tungabhadra River for both kingdoms and resulted in the death of king Rajadhiraja.

Rajendra's reign was followed by three of his sons in succession: Rajadhiraja I, Rajendra II, and Virarajendra. In his eagerness to restore the Chola hegemony over Vengi to its former absolute state, Rajadhiraja I (1042–1052) led an expedition into the Vengi country in 1044–1045. He fought a battle at Dhannada and compelled the Western Chalukyan army along with Vijayaditya VII to retreat in disorder. He then entered into the Western Chalukyan dominions and set fire to the Kollipaka fort on the frontier between the Kalyani and Vengi territories.

This brought relief for Rajaraja Narendra who was now firmly in control at Vengi, with Rajadhiraja I proceeding all the way up to the Chalukyan capital, displacing the Chalukyan king Someshvara I and performing his coronation at Manyakheta and collecting tribute from the defeated king, who had fled the battlefield. However, while the Chalukyans kept creating trouble through Vijayaditya VII Vengi remained firmly in control of the Cholas. Someshvara I however, again launched an attack on Vengi and then the Cholas in 1054.

After Rajadhiraja died, Rajendra II crowned himself on the battlefield. He galvanized the Chola army, crushing the Chalukyas under Someshvara I in the process. Again, the Chalukya king fled the battle field leaving his queen and riches behind in the possession of the victorious Chola army. The Cholas consolidated their hold on both Vengi and Kalinga. Although from time to time there were skirmishes with the Chalukyas, they were repeatedly crushed by both the Cholas and the Vengi princes, who openly professed loyalty to the Chola empire. The death of Rajaraja Narendra in 1061 offered another opportunity for the Kalyani court to strengthen its hold on Vengi. Vijayaditya VII seized Vengi. With the consent of the Kalyani court, which he had served for many years, he established himself permanently in the kingdom. Meanwhile, prince Rajendra Chalukya, son of Rajaraja Narendra through the Chola princess Ammangai was brought up in the Chola harem. Rajendra Chalukya, married Madhurantakidevi, the daughter of RajendraII. In order to restore him on the Vengi throne, RajendraII sent his son Rajamahendra and brother ViraRajendraagainst the Western Chalukyas and Vijayaditya VII. The Chola forces marched against Gangavadi and drove away the Chalukyas. Virarajendra then marched against Vengi and probably killed Saktivarman II, son of Vijayaditya VII.

In the midst of this, in 1063, Rajendra II died and, as his son Rajamahendra had predeceased him, Virarajendra went back to Gangaikonda Cholapuram and was crowned the Chola king (1063–1070). He managed to split the Western Chalukya kingdom by convincing a Chalukya prince, Vikramaditya IV, to become his son-in-law and to seize the throne of Kalyani for himself. When Virarajendra died in 1070, he was succeeded by his son Adhirajendra, but the latter was assassinated a few months later, leaving the Chola dynasty was without a lineal successor in the Vijayalaya Chola line.

Later Cholas

Marital and political alliances between the Eastern Chalukyas began during the reign of Rajaraja following his invasion of Vengi. Rajaraja Chola's daughter married Chalukya prince Vimaladitya[27] and Rajendra Chola's daughter Ammanga Devi was married to the Eastern Chalukya prince Rajaraja Narendra.[28] Virarajendra Chola's son, Athirajendra Chola, was assassinated in a civil disturbance in 1070, and Kulothunga Chola I, the son of Ammanga Devi and Rajaraja Narendra, ascended the Chola throne. Thus began the Later Chola dynasty.[29]

The Later Chola dynasty was led by capable rulers such as Kulothunga I, his son Vikrama Chola, other successors like Rajaraja II, Rajadhiraja II, and Kulothunga III, who conquered Kalinga, Ilam, and Kataha. However, the rule of the later Cholas between 1218, starting with Rajaraja III, to the last emperor Rajendra III was not as strong as those of the emperors between 850 and 1215. Around 1118, they lost control of Vengi to the Western Chalukya and Gangavadi (southern Mysore districts) to the Hoysala Empire. However, these were only temporary setbacks, because immediately following the accession of king Vikrama Chola, the son and successor of Kulothunga Chola I, the Cholas lost no time in recovering the province of Vengi by defeating Chalukya Someshvara III and also recovering Gangavadi from the Hoysalas. The Chola empire, though not as strong as between 850 and 1150, was still largely territorially intact under Rajaraja II (1146–1175) a fact attested by the construction and completion of the third grand Chola architectural marvel, the chariot-shaped Airavatesvara Temple at Dharasuram on the outskirts of modern Kumbakonam. Chola administration and territorial integrity until the rule of Kulothunga Chola III was stable and very prosperous up to 1215, but during his rule itself, the decline of the Chola power started following his defeat by Maravarman Sundara Pandiyan II in 1215–16.[30] Subsequently, the Cholas also lost control of the island of Lanka and were driven out by the revival of Sinhala power.

In continuation of the decline, also marked by the resurgence of the Pandyan dynasty as the most powerful rulers in South India, a lack of a controlling central administration in its erstwhile Pandyan territories prompted a number of claimants to the Pandya throne to cause a civil war in which the Sinhalas and the Cholas were involved by proxy. Details of the Pandyan civil war and the role played by the Cholas and Sinhalas, are present in the Mahavamsa as well as the Pallavarayanpettai Inscriptions.[31][32]

For three generations the Eastern Chalukyan princes had married in to the imperial Chola family and they had come to feel that they belonged to it as much as the Eastern Chalukya dynasty. One of the Chalukya princes was Rajendra Chalukya of Vengi, who had "spent his childhood days in Gangaikonda Cholapuram and was a familiar favourite to the princes and the people of the Chola country" according to Kalingathuparani, an epic written in praise of him. He moved into the political vacuum created by the death of Adhirajendra and established himself on the Chola throne as Kulottunga I (1070–1122), beginning the Later Chola or Chalukya-Chola period.[33]

Kulothunga I reconciled himself with his uncle Vijayaditya VII and allowed him to rule Vengi for the rest of his life. With Vijayaditya's death in 1075 CE, the Eastern Chalukya line came to an end. Vengi became a province of the Chola Empire. Kulottunga Chola I administered the province through his sons by sending them as Viceroys. However, there was a prolonged fight between him and Vikramaditya VI. Kulothunga's long reign was characterized by unparalleled success and prosperity. He avoided unnecessary wars and earned the true admiration of his subjects. His successes resulted in the wellbeing of the empire for the next 100 years. However the first seeds of the impending troubles were sown in his reign. Kulothunga lost the territories in the island of Lanka and more seriously, the Pandya territories were beginning to slip away from Chola control.

Diminished empire

The Cholas, under Rajaraja Chola III and later, his successor Rajendra Chola III, were quite weak and therefore, experienced continuous trouble. One feudatory, the Kadava chieftain Kopperunchinga I, even held Rajaraja Chola III as hostage for sometime.[34] At the close of the 12th century, the growing influence of the Hoysalas replaced the declining Chalukyas as the main player in the Kannada country, but they too faced constant trouble from the Seunas and the Kalachuris, who were occupying Chalukya capital because those empires were their new rivals. So naturally, the Hoysalas found it convenient to have friendly relations with the Cholas from the time of Kulothunga Chola III, who had defeated Hoysala Veera Ballala II, who had subsequent marital relations with the Chola monarch. This continued during the time of Rajaraja Chola III the son and successor of Kulothunga Chola III[30][35]

The Hoysalas played a divisive role in the politics of the Tamil country during this period. They thoroughly exploited the lack of unity among the Tamil kingdoms and alternately supported one Tamil kingdom against the other thereby preventing both the Cholas and Pandyas from rising to their full potential. During the period of Rajaraja III, the Hoysalas sided with the Cholas and defeated the Kadava chieftain Kopperunjinga and the Pandyas and established a presence in the Tamil country. Rajendra Chola III, who succeeded Rajaraja III, was a much better ruler who took bold steps to revive the Chola fortunes. He led successful expeditions to the north as attested by his epigraphs found as far as Cuddappah.[36] He also defeated two Pandya princes one of whom was Maravarman Sundara Pandya II and briefly made the Pandyas submit to the Chola overlordship. The Hoysalas, under Vira Someswara, were quick to intervene and this time they sided with the Pandyas and repulsed the Cholas in order to counter the latter's revival.[37] The Pandyas in the south had risen to the rank of a great power who ultimately banished the Hoysalas from Malanadu or Kannada country, who were allies of the Cholas from Tamil country and the demise of the Cholas themselves ultimately was caused by the Pandyas in 1279. The Pandyas first steadily gained control of the Tamil country as well as territories in Sri Lanka, southern Chera country, Telugu country under Maravarman Sundara Pandiyan II and his able successor Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan before inflicting several defeats on the joint forces of the Cholas under Rajaraja Chola III, and the Hoysalas under Someshwara, his son Ramanatha.[30] The Pandyans gradually became major players in the Tamil country from 1215 and intelligently consolidated their position in Madurai-Rameswaram-Ilam-southern Chera country and Kanyakumari belt, and had been steadily increasing their territories in the Kaveri belt between Dindigul-Tiruchy-Karur-Satyamangalam as well as in the Kaveri Delta, i.e. Thanjavur-Mayuram-Chidambaram-Vriddhachalam-Kanchi, finally marching all the way up to Arcot—Tirumalai-Nellore-Visayawadai-Vengi-Kalingam belt by 1250.[38]

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

The Pandyas steadily routed both the Hoysalas and the Cholas.[39] They also dispossessed the Hoysalas, by defeating them under Jatavarman Sundara Pandiyan at Kannanur Kuppam.[40] At the close of Rajendra's reign, the Pandyan empire was at the height of prosperity and had taken the place of the Chola empire in the eyes of the foreign observers.[41] The last recorded date of Rajendra III is 1279. There is no evidence that Rajendra was followed immediately by another Chola prince.[42][43] The Hoysalas were routed from Kannanur Kuppam around 1279 by Kulasekhara Pandiyan and in the same war the last Chola emperor Rajendra III was routed and the Chola empire ceased to exist thereafter. Thus the Chola empire was completely overshadowed by the Pandyan empire and sank into obscurity by the end of the 13th century and until period of the Vijayanagara Empire.[44][43] In the early 16th century, Virasekhara Chola, king of Tanjore rose out of obscurity and plundered the dominions of the then Pandya prince in south. The Pandya who was under the protection of the Vijayanagara appealed to the emperor and the Raya accordingly directed his agent (Karyakartta) Nagama Nayaka who was stationed in the south to put down the Chola. Nagama Nayaka then defeated the Chola but to everyone's surprise the once loyal officer of Krishnadeva Raya defied the emperor for some reason and decided to keep Madurai for himself. Krishnadeva Raya is then said to have dispatched Nagama's son, Viswanatha who defeated his father and restored Madurai to Vijayanagara.[45] The fate of Virasekhara Chola, the last of the line of Cholas is not known. It is speculated that he either fell in battle or was put to death along with his heirs during his encounter with Vijayanagara.[46][47]

Administration

Government

In the age of the Cholas, the whole of South India was for the first time brought under a single government.[lower-alpha 1]

The Cholas' system of government was monarchical, as in the Sangam age.[48] However, there was little in common between the local chiefdoms of the earlier period and the imperial-like states of Rajaraja Chola and his successors.[49] Aside from the early capital at Thanjavur and the later on at Gangaikonda Cholapuram, Kanchipuram and Madurai were considered to be regional capitals in which occasional courts were held. The king was the supreme leader and a benevolent authoritarian. His administrative role consisted of issuing oral commands to responsible officers when representations were made to him. Due to the lack of a legislature or a legislative system in the modern sense, the fairness of king's orders dependent on his morality and belief in Dharma. The Chola kings built temples and endowed them with great wealth. The temples acted not only as places of worship but also as centres of economic activity, benefiting the community as a whole.[50] Some of the output of villages throughout the kingdom was given to temples that reinvested some of the wealth accumulated as loans to the settlements.[51] The Chola empire was divided into several provinces called mandalams which were further divided into valanadus, which were subdivided into units called kottams or kutrams.[52] According to Kathleen Gough, during the Chola period the Vellalar were the "dominant secular aristocratic caste ... providing the courtiers, most of the army officers, the lower ranks of the kingdom's bureaucracy, and the upper layer of the peasantry".[53]

Before the reign of Rajaraja Chola I huge parts of the Chola territory were ruled by hereditary lords and local princes who were in a loose alliance with the Chola rulers. Thereafter, until the reign of Vikrama Chola in 1133 when the Chola power was at its peak, these hereditary lords and local princes virtually vanished from the Chola records and were either replaced or turned into dependent officials. Through these dependent officials the administration was improved and the Chola kings were able to exercise a closer control over the different parts of the empire.[54] There was an expansion of the administrative structure, particularly from the reign of Rajaraja Chola I onwards. The government at this time had a large land revenue department, consisting of several tiers, which was largely concerned with maintaining accounts. The assessment and collection of revenue were undertaken by corporate bodies such as the ur, nadu, sabha, nagaram and sometimes by local chieftains who passed the revenue to the centre. During the reign of Rajaraja Chola I, the state initiated a massive project of land survey and assessment and there was a reorganisation of the empire into units known as valanadus.[55]

The order of the King was first communicated by the executive officer to the local authorities. Afterwards the records of the transaction was drawn up and attested by a number of witnesses who were either local magnates or government officers.[56]

At local government level, every village was a self-governing unit. A number of villages constituted a larger entity known as a kurram, nadu or kottam, depending on the area.[57][58][59] A number of kurrams constituted a valanadu.[60] These structures underwent constant change and refinement throughout the Chola period.[61]

Justice was mostly a local matter in the Chola empire; minor disputes were settled at the village level.[59] Punishment for minor crimes were in the form of fines or a direction for the offender to donate to some charitable endowment. Even crimes such as manslaughter or murder were punished with fines. Crimes of the state, such as treason, were heard and decided by the king himself; the typical punishment in these cases was either execution or confiscation of property.[62]

Military

The Chola military had four elements, comprising the cavalry, the elephant corps, several divisions of infantry and a navy.[63] The Emperor was the supreme commander. There were regiments of bowmen and swordsmen while the swordsmen were the most permanent and dependable troops. The Chola army was spread all over the country and was stationed in local garrisons or military camps known as Kodagams. The elephants played a major role in the army and the empire had numerous war elephants. These carried houses or huge Howdahs on their backs, full of soldiers who shot arrows at long range and who fought with spears at close quarters.[64] The Chola army composed chiefly of Kaikolars (men with stronger arms), which were royal troops receiving regular payments from the treasury (e.g. Arul mozhideva-terinda-kaikola padai; in this, arulmozhideva is the king's name, terinda means well known, and padai means regime).[65]

The Chola rulers built several palaces and fortifications to protect their cities. The fortifications were mostly made up of bricks but other materials like stone, wood and mud were also used.[66][67] According to the ancient Tamil text Silappadikaram, the Tamil kings defended their forts with catapults that threw stones, huge cauldrons of boiling water or molten lead, and hooks, chains and traps.[68][69]

The soldiers of the Chola empire used weapons such as swords, bows, javelins, spears and shields which were made up of steel.[70] Particularly the famous Wootz steel, which has a long history in south India dating back to the period before the Christian era, seems also be used to produce weapons.[71] Kallar served in the armies of the Chola kings.[72]

The Chola navy was the zenith of ancient India sea power.[64] It played a vital role in the expansion of the empire, including the conquest of the Ceylon islands and naval raids on Srivijaya.[73] The navy grew both in size and status during the medieval Cholas reign. The Chola admirals commanded much respect and prestige. The navy commanders also acted as diplomats in some instances. From 900 to 1100, the navy had grown from a small backwater entity to that of a potent power projection and diplomatic symbol in all of Asia, but was gradually reduced in significance when the Cholas fought land battles subjugating the Chalukyas of the Andhra-Kannada area in South India.[74]

A martial art called Silambam was patronised by the Chola rulers. Ancient and medieval Tamil texts mention different forms of martial traditions but the ultimate expression of the loyalty of the warrior to his commander was a form of martial suicide called Navakandam. The medieval Kalingathu Parani text, which celebrates the victory of Kulothunga Chola I and his general in the battle for Kalinga, describes the practice in detail.

Economy

Land revenue and trade tax were the main source of income.[75] The Chola rulers issued their coins in gold, silver and copper.[76] The Chola economy was based on three tiers—at the local level, agricultural settlements formed the foundation to commercial towns nagaram, which acted as redistribution centres for externally produced items bound for consumption in the local economy and as sources of products made by nagaram artisans for the international trade. At the top of this economic pyramid were the elite merchant groups (samayam) who organised and dominated the regions international maritime trade.[77]

One of the main articles which were exported to foreign countries were cotton cloth.[78] Uraiyur, the capital of the early Chola rulers, was a famous centre for cotton textiles which were praised by Tamil poets.[79][80] The Chola rulers actively encouraged the weaving industry and derived revenue from it.[81] During this period the weavers started to organise themselves into guilds.[82] The weavers had their own residential sector in all towns. The most important weaving communities in early medieval times were the Saliyar and Kaikolar.[81] During the Chola period silk weaving attained a high degree and Kanchipuram became one of the main centres for silk.[83][84]

Metal crafts reached its zenith during the 10th to 11th centuries because the Chola rulers like Chembian Maadevi extended their patronage to metal craftsmen.[85] Wootz steel was a major export item.[86]

The farmers occupied one of the highest positions in society.[87] These were the Vellalar community who formed the nobility or the landed aristocracy of the country and who were economically a powerful group.[87][88] Agriculture was the principal occupation for many people. Besides the landowners, there were others dependent on agriculture.[89] The Vellalar community was the dominant secular aristocratic caste under the Chola rulers, providing the courtiers, most of the army officers, the lower ranks of the bureaucracy and the upper layer of the peasantry.[53]

In almost all villages the distinction between persons paying the land-tax (iraikudigal) and those who did not was clearly established. There was a class of hired day-labourers who assisted in agricultural operations on the estates of other people and received a daily wage. All cultivable land was held in one of the three broad classes of tenure which can be distinguished as peasant proprietorship called vellan-vagai, service tenure and eleemosynary tenure resulting from charitable gifts.[90] The vellan-vagai was the ordinary ryotwari village of modern times, having direct relations with the government and paying a land-tax liable to revision from time to time.[77] The vellan-vagai villages fell into two broad classes: one directly remitting a variable annual revenue to the state and the other paying dues of a more or less fixed character to the public institutions like temples to which they were assigned.[91] The prosperity of an agricultural country depends to a large extent on the facilities provided for irrigation. Apart from sinking wells and excavating tanks, the Chola rulers threw mighty stone dams across the Kaveri and other rivers, and cut out channels to distribute water over large tracts of land.[92] Rajendra Chola I dug near his capital an artificial lake, which was filled with water from the Kolerun and the Vellar rivers.[91]

There existed a brisk internal trade in several articles carried on by the organised mercantile corporations in various parts of the country. The metal industries and the jewellers art had reached a high degree of excellence. The manufacture of sea-salt was carried on under government supervision and control. Trade was carried on by merchants organised in guilds. The guilds described sometimes by the terms nanadesis were a powerful autonomous corporation of merchants which visited different countries in the course of their trade. They had their own mercenary army for the protection of their merchandise. There were also local organisations of merchants called "nagaram" in big centres of trade like Kanchipuram and Mamallapuram.[93][91]

Hospitals

_near_Kanchipuram_-_top_view.jpeg.webp)

Hospitals were maintained by the Chola kings, whose government gave lands for that purpose. The Tirumukkudal inscription shows that a hospital was named after Vira Chola. Many diseases were cured by the doctors of the hospital, which was under the control of a chief physician who was paid annually 80 Kalams of paddy, 8 Kasus and a grant of land. Apart from the doctors, other remunerated staff included a nurse, barber (who performed minor operations) and a waterman.[94]

The Chola queen Kundavai also established a hospital at Tanjavur and gave land for the perpetual maintenance of it.[95]

Society

During the Chola period several guilds, communities, and castes emerged. The guild was one of the most significant institutions of south India and merchants organised themselves into guilds. The best known of these were the Manigramam and Ayyavole guilds though other guilds such as Anjuvannam and Valanjiyar were also in existence.[96] The farmers occupied one of the highest positions in society. These were the Vellalar community who formed the nobility or the landed aristocracy of the country and who were economically a powerful group.[87][88] The Vellalar community was the dominant secular aristocratic caste under the Chola rulers, providing the courtiers, most of the army officers, the lower ranks of the bureaucracy and the upper layer of the peasantry.[53] The Vellalar were also sent to northern Sri Lanka by the Chola rulers as settlers.[97] The Ulavar community were working in the field which was associated with agriculture and the peasants were known as Kalamar.[87]

The Kaikolar community were weavers and merchants but they also maintained armies. During the Chola period they had predominant trading and military roles.[98] During the reign of the Imperial Chola rulers (10th–13th centuries) there were major changes in the temple administration and land ownership. There was more involvement of non-Brahmin elements in the temple administration. This can be attributed to the shift in money power. Skilled classes like the weavers and the merchant-class had become prosperous. Land ownership was no longer a privilege of the Brahmins (priest caste) and the Vellalar land owners.[99]

There is little information on the size and the density of the population during the Chola reign[100] The stability in the core Chola region enabled the people to lead a productive and contented life. However, there were reports of widespread famine caused by natural calamities.[101]

The quality of the inscriptions of the regime indicates a high level of literacy and education. The text in these inscriptions was written by court poets and engraved by talented artisans. Education in the contemporary sense was not considered important; there is circumstantial evidence to suggest that some village councils organised schools to teach the basics of reading and writing to children,[102] although there is no evidence of systematic educational system for the masses.[103] Vocational education was through hereditary training in which the father passed on his skills to his sons. Tamil was the medium of education for the masses; Religious monasteries (matha or gatika) were centres of learning and received government support.[104]

Under the Chola Kings, there was generally an emphasis on a fair justice system, and the Kings were often described as Sengol-valavan, the king who established just rule; and the king was warned by the priests that royal justice would ensure a happy future for him here, and that injustice would lead to divine punishment.[105][106]

Foreign trade

The Cholas excelled in foreign trade and maritime activity, extending their influence overseas to China and Southeast Asia.[107] Towards the end of the 9th century, southern India had developed extensive maritime and commercial activity.[108] The south Indian guilds played a major role in interregional and overseas trade. The best known of these were the Manigramam and Ayyavole guilds who followed the conquering Chola armies.[109] The encouragement by the Chola court furthered the expansion of Tamil merchant associations such as the Ayyavole and Manigramam guilds into Southeast Asia and China.[110] The Cholas, being in possession of parts of both the west and the east coasts of peninsular India, were at the forefront of these ventures.[111][112] The Tang dynasty of China, the Srivijaya Empire under the Sailendras, and the Abbasid Kalifat at Baghdad were the main trading partners.[113]

Some credit for the emergence of a world market must also go to the dynasty. It played a significant role in linking the markets of China to the rest of the world. The market structure and economic policies of the Chola dynasty were more conducive to a large-scale, cross-regional market trade than those enacted by the Chinese Song Dynasty. A Chola record gives their rationale for engagement in foreign trade: "Make the merchants of distant foreign countries who import elephants and good horses attach to yourself by providing them with villages and decent dwellings in the city, by affording them daily audience, presents and allowing them profits. Then those articles will never go to your enemies."[114]

Song dynasty reports record that an embassy from Chulian (Chola) reached the Chinese court in 1077,[115][116] and that the king of the Chulian at the time, Kulothunga I, was called Ti-hua-kia-lo. This embassy was a trading venture and was highly profitable to the visitors, who returned with copper coins in exchange for articles of tribute, including glass and spices.[117] Probably, the motive behind Rajendra's expedition to Srivijaya was the protection of the merchants' interests.[118]

Canals and water tanks

There was tremendous agrarian expansion during the rule of the imperial Chola dynasty (c. 900–1270) all over Tamil Nadu and particularly in the Kaveri Basin. Most of the canals of the Kaveri River belongs to this period e.g. Uyyakondan canal, Rajendran vaykkal, Sembian Mahadegvi vaykkal. There was a well-developed and highly efficient system of water management from the village level upwards. The increase in the royal patronage and also the number of devadana and bramadeya lands which increased the role of the temples and village assemblies in the field. Committees like eri-variyam (tank-committee) and totta-variam (garden committees) were active as also the temples with their vast resources in land, men and money. The water tanks that came up during the Chola period are too many to be listed here. But a few most outstanding may be briefly mentioned. Rajendra Chola built a huge tank named Solagangam in his capital city Gangaikonda Solapuram and was described as the liquid pillar of victory. About 16 miles long, it was provided with sluices and canals for irrigating the lands in the neighbouring areas. Another very large lake of this period, which even today seems an important source of irrigation was the Viranameri near Kattumannarkoil in South Arcot district founded by Parantaka Chola. Other famous lakes of this period are Madurantakam, Sundra-cholapereri, Kundavai-Pereri (after a Chola queen).[119]

Art and architecture

Architecture

The Cholas continued the temple-building traditions of the Pallava dynasty and contributed significantly to the Dravidian temple design.[120] They built a number of Shiva temples along the banks of the river Kaveri. The template for these and future temples was formulated by Aditya I and Parantaka.[121][122][123] The Chola temple architecture has been appreciated for its magnificence as well as delicate workmanship, ostensibly following the rich traditions of the past bequeathed to them by the Pallava Dynasty.[124] Architectural historian James Fergusson says that "the Chola artists conceived like giants and finished like jewelers".[124] A new development in Chola art that characterised the Dravidian architecture in later times was the addition of a huge gateway called gopuram to the enclosure of the temple, which had gradually taken its form and attained maturity under the Pandya dynasty.[124] The Chola school of art also spread to Southeast Asia and influenced the architecture and art of Southeast Asia.[125][126]

Temple building received great impetus from the conquests and the genius of Rajaraja Chola and his son Rajendra Chola I.[127] The maturity and grandeur to which the Chola architecture had evolved found expression in the two temples of Thanjavur and Gangaikondacholapuram. The magnificent Shiva temple of Thanjavur, completed around 1009, is a fitting memorial to the material achievements of the time of Rajaraja. The largest and tallest of all Indian temples of its time, it is at the apex of South Indian architecture. The temple of Gangaikondacholisvaram at Gangaikondacholapuram, the creation of Rajendra Chola, was intended to excel its predecessor. Completed around 1030, only two decades after the temple at Thanjavur and in the same style, the greater elaboration in its appearance attests the more affluent state of the Chola empire under Rajendra.[120][128] The Brihadisvara Temple, the temple of Gangaikondacholisvaram and the Airavatesvara Temple at Darasuram were declared as World Heritage Sites by the UNESCO and are referred to as the Great living Chola temples.[129]

The Chola period is also remarkable for its sculptures and bronzes.[130][131][132] Among the existing specimens in museums around the world and in the temples of South India may be seen many fine figures of Shiva in various forms, such as Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi, and the Shaivite saints.[120] Though conforming generally to the iconographic conventions established by long tradition, the sculptors worked with great freedom in the 11th and the 12th centuries to achieve a classic grace and grandeur. The best example of this can be seen in the form of Nataraja the Divine Dancer.[133][lower-alpha 2]

Literature

Literature florished in the Chola Empire. Kambar flourished during the reign of Kulothunga III. His Ramavataram (also referred to as Kambaramayanam) is an epic of Tamil literature, and although the author states that he followed Valmiki's Ramayana, it is generally accepted that his work is not a simple translation or adaptation of the Sanskrit epic.[135] He imports into his narration the colour and landscape of his own time; his description of Kosala is an idealised account of the features of the Chola country.[136][137][138]

Jayamkondar's Kalingattuparani is an example of narrative poetry that draws a clear boundary between history and fictitious conventions. This describes the events during Kulothunga's war in Kalinga and depicts not only the pomp and circumstance of war, but the gruesome details of the field.[138][139] The Tamil poet Ottakuttan was a contemporary of Kulothunga I and served at the courts of three of Kulothunga's successors.[140][141] Ottakuttan wrote Kulothunga Cholan Ula, a poem extolling the virtues of the Chola king.[142]

Nannul is a Chola era work on Tamil grammar. It discusses all five branches of grammar and, according to Berthold Spuler, is still relevant today and is one of the most distinguished normative grammars of literary Tamil.[143]

The Telugu Choda period was in particular significant for the development of Telugu literature under the patronage of the rulers. It was the age in which the great Telugu poets Tikkana, Ketana, Marana and Somana enriched the literature with their contributions. Tikkana Somayaji wrote Nirvachanottara Ramayanamu and Andhra Mahabharatamu. Abhinava Dandi Ketana wrote Dasakumaracharitramu, Vijnaneswaramu and Andhra Bhashabhushanamu. Marana wrote Markandeya Purana in Telugu. Somana wrote Basava Purana. Tikkana is one of the kavitrayam who translated Mahabharata into Telugu language.[144]

Of the devotional literature, the arrangement of the Shaivite canon into eleven books was the work of Nambi Andar Nambi, who lived close to the end of the 10th century.[145][146] However, relatively few Vaishnavite works were composed during the Later Chola period, possibly because of the rulers' apparent animosity towards them.[147]

Religion

In general, Cholas were followers of Hinduism. While the Cholas did build their largest and most important temple dedicated to Shiva, it can be by no means concluded that either they were followers of Shaivism only or that they were not favourably disposed to other faiths. This is borne out by the fact that the second Chola king, Aditya I (871–903), built temples for Shiva and also for Vishnu. Inscriptions of 890 refer to his contributions to the construction of the Ranganatha Temple at Srirangapatnam in the country of the Western Gangas, who were both his feudatories and had connections by marriage with him. He also pronounced that the great temples of Shiva and the Ranganatha temple were to be the Kuladhanam of the Chola emperors.[148]

Parantaka II was a devotee of the reclining Vishnu (Vadivu Azhagiya Nambi) at Anbil, on the banks of the Kaveri river on the outskirts of Tiruchy, to whom he gave numerous gifts and embellishments. He also prayed before him before his embarking on war to regain the territories in and around Kanchi and Arcot from the waning Rashtrakutas and while leading expeditions against both Madurai and Ilam (Sri Lanka).[149] Parantaka I and Parantaka Chola II endowed and built temples for Shiva and Vishnu.[150] Rajaraja Chola I patronised Buddhists and provided for the construction of the Chudamani Vihara, a Buddhist monastery in Nagapattinam, at the request of Sri Chulamanivarman, the Srivijaya Sailendra king.[151][152]

During the period of the Later Cholas, there are alleged to have been instances of intolerance towards Vaishnavites[153] especially towards their acharya, Ramanuja.[154] A Chola sovereign called Krimikanta Chola is said to have persecuted Ramanuja. Some scholars identify Kulothunga Chola II with Krimikanta Chola or worm-necked Chola, so called as he is said to have suffered from cancer of the throat or neck. The latter finds mention in the vaishnava Guruparampara and is said to have been a strong opponent of the vaishnavas. The work Parpannamritam (17th century) refers to the Chola king called Krimikanta who is said to have removed the Govindaraja idol from the Chidambaram Nataraja temple.[155] However, according to "Koil Olugu" (temple records) of the Srirangam temple, Kulottunga Chola II was the son of Krimikanta Chola. The former, unlike his father, is said to have been a repentant son who supported vaishnavism.[156][157] Ramanuja is said to have made Kulottunga II as a disciple of his nephew, Dasarathi. The king then granted the management of the Ranganathaswamy temple to Dasarathi and his descendants as per the wish of Ramanuja.[158][159] Historian Nilakanta Sastri identifies Krimikanta Chola with Adhirajendra Chola or Virarajendra Chola with whom the main line (Vijayalaya line) ended.[160][161] There is an inscription from 1160 AD which states that the custodians of Shiva temples who had social intercourses with Vaishnavites would forfeit their property. However, this is more of a direction to the Shaivite community by its religious heads than any kind of dictat by a Chola emperor. While Chola kings built their largest temples for Shiva and even while emperors like Rajaraja Chola I held titles like Sivapadasekharan, in none of their inscriptions did the Chola emperors proclaim that their clan only and solely followed Shaivism or that Shaivism was the state religion during their rule.[162][163][164]

Family tree

| Medieval Cholas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Emperors

| Ruler | Reign | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vijayalaya Chola | 848–870 | Founder of the Chola empire, and descendant of the Early Cholas. | |

| Aditya I | 870–907 | ||

| Parantaka I | 907–955 | ||

| Gandaraditya | 955–957 | Ruled jointly. | |

| Arinjaya | 956–957 | ||

| Parantaka II | 957–970 | ||

| Uttama | 970–985 | ||

| Rajaraja I the Great | .jpg.webp) |

985–1014 | |

| Rajendra I |  |

1014–1044 | |

| Rajadhiraja I |  |

1044–1054 | |

| Rajendra II | 1054–1063 | ||

| Virarajendra | 1063–1070 | ||

| Athirajendra | 1070 | Left no heirs. | |

| Kulothunga I |  |

1070–1122 | Son of Amangai Devi Chola, daughter of Rajendra I, and Rajaraja Narendra, ruler of Eastern Chalukya dynasty. Kolothunga's reign started the period which was known as Chalukya-Chola dynasty or simply Later Cholas. |

| Vikrama | 1122–1135 | ||

| Kulothunga II |  |

1135–1150 | Grandson of the previous. |

| Rajaraja II |  |

1150–1173 | |

| Rajadhiraja II | 1173–1178 | Grandson of king Vikrama Chola. | |

| Kulothunga III |  |

1178–1218 | |

| Rajaraja III | 1218–1256 | ||

| Rajendra III | 1256–1279 | Last Chola ruler, defeated by the Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan I of the Pandya dynasty. After the war, the remaining Chola royal bloods were reduced to the state of being chieftains by the Pandyan forces. | |

Notes

- Kaimal, Padma (May 1992). "Art of the Imperial Cholas. By Vidya Dehejia. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. xv, 148 pp. 36.00". The Journal of Asian Studies (book review). 51 (2): 414–416. doi:10.2307/2058068. ISSN 1752-0401. JSTOR 2058068. S2CID 163175500.

- K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, p. 158

- K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, p. 195–196

- Keay 2011, p. 215.

- Vasudevan, pp. 20–22

- Keay 2011, pp. 217–218.

- Promsak Jermsawatdi, Thai Art with Indian Influences, p. 57

- John Stewart Bowman, Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, p. 335

- Sen (1999), pp. 477–478

- Gupta, S.p (1977). Readings in South Indian History. pp. 62–63.

- Dehejia (1990), p. xiv

- Kulke & Rothermund (2001), pp. 122–123

- Eraly (2011), p. 67

- Sen (1999), pp. 373

- Kulke & Rothermund (2001), p. 115

- Eraly (2011), p. 68

- "Endowments to the Temple". Archaeological Survey of India.

- Balaji Sadasivan, The Dancing Girl: A History of Early India, p.133

- Farooqui Salma Ahmed, Salma Ahmed Farooqui, A Comprehensive History of Medieval India, p.25

- Ronald Findlay, Kevin H. O'Rourke, Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium, p.67

- Geoffrey C. Gunn, History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000–1800, p.43

- Sen (2009), p. 91

- Tansen Sen, Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, p.226

- Kalā: The Journal of Indian Art History Congress, The Congress, 1995, p.31

- Sastri (1984), pp. 194–210

- Majumdar (1987), p. 407

- Majumdar (1987), p. 405

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 120

- Majumdar (1987), p. 408

- Tripathi (1967), p. 471

- South Indian Inscriptions, Vol. 12

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), pp. 128–129

- Government Oriental Manuscripts Library. Madras Government Oriental Series, Issue 157. Tamil Nadu, India. p. 729.

- Sastri (2002), p. 194

- Majumdar (1987), p. 410

- Journal of the Sri Venkatesvara Oriental Institute. Sri Venkatesvara Oriental Institute. 5–7: 64.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 487.

- South India and Her Muhammadan Invaders by S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar pp. 40–41

- Sastri (2002), pp. 195–196

- Sastri (2002), p. 196

- Tripathi (1967), p. 485

- Sastri (2002), p. 197

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 130

- Tripathi (1967), p. 472

- P. K. S. Raja (1966). Mediaeval Kerala. Navakerala Co-op Publishing House. p. 47.

- Ē. Kē Cēṣāttiri (1998). Sri Brihadisvara, the Great Temple of Thanjavur. Nile Books. p. 24.

- Stein, Burton (1990). "Vijayanagara". The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 57.

- Kulke & Rothermund (2001), p. 104

- Stein (1998), p. 26

- Vasudevan (2003), pp. 20–22

- Francis D. K. Ching, Mark M. Jarzombek, Vikramaditya Prakash, A Global History of Architecture, p.338

- N. Jayapalan, History of India, p.171, ISBN 81-7156-914-5

- Gough (2008), p. 29

- Talbot (2001), p. 172.

- Singh (2008), p. 590

- U. B. Singh, Administrative System in India: Vedic Age to 1947, p.77

- Tripathi (1967), pp. 474–475

- Stein (1998), p. 20

- Sastri (2002), p. 185

- Sastri (2002), p. 150

- Sastri (1984), p. 465

- Sastri (1984), p. 477

- Sakhuja & Sakhuja (2009), p. 88

- Barua (2005), p. 18

- Sen (1999), p. 491, Kaikolar.

- Dehejia (1990), p. 79

- Subbarayalu (2009), pp. 97–99

- Eraly (2011), p. 176

- Rajasuriar (1998), p. 15

- Sen (1999), p. 205

- Menon, R. V. G., Technology and Society, p.15

- Historical Dictionary of the Tamils (2nd ed.). The Scarecrow Press. 2007. p. 105. ISBN 9780810864450.

- Pradeep Barua, The State at War in South Asia, p.17

- Sastri (2002), p. 175

- Showick Thorpe, Edgar Thorpe, The Pearson General Studies Manual 2009, 1st ed., p.59

- Singh (2008), p. 54

- Schmidt (1995), p. 32

- Devare (2009), p. 179

- Eraly (2011), p. 208

- Ramaswamy (2007), p. 20

- Singh (2008), p. 599

- Radhika Seshan, Trade and Politics on the Coromandel Coast: Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth centuries, p.18

- G. K. Ghosh, Shukla Ghosh, Indian Textiles: Past and Present, p.123–124

- P. V. L. Narasimha Rao, Kanchipuram: Land of Legends, Saints and Temples, p.134

- Ramaswamy (2007), p. 51

- Mukherjee (2011), p. 105

- S. Ganeshram, History of People and Their Environs: Essays in Honour of Prof. B. S. Chandrababu, p.319

- Singh (2008), p. 592

- Sen (1999), pp. 490–492

- Reddy, Indian History, p. B57

- Mukund (1999), pp. 30–32

- Ramaswamy (2007), p. 86

- Rothermund (1993), p. 9

- N. Jayapalan, Economic History of India, p.49

- Balasubrahmanyam Venkataraman, Temple art under the Chola queens, p.72

- Mukund (1999), p. 29-30

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam (2004), p. 104

- Carla M. Sinopoli, The Political Economy of Craft Production: Crafting Empire in South India, p.188

- Sadarangani (2004), p. 16

- Sastri (2002), p. 284

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), pp. 125, 129

- Scharfe (2002), p. 180

- Italian traveler Pietro Della Valle (1623) gave a vivid account of the village schools in South India. These accounts reflect the system of primary education in existence until modern times in Tamil Nadu.

- Sastri (2002), p. 293

- Balasubrahmanyam, S (1977). Middle Chola Temples Rajaraja I to Kulottunga I (A.D. 985-1070). Oriental Press. p. 291. ISBN 9789060236079.

- Subrahmanian, N (1971), History of Tamilnad (to A.D. 1336), Koodal Publishers, retrieved 12 June 2023

- Kulke & Rothermund (2001), pp. 116–117

- Kulke & Rothermund (2001), pp. 12, 118

- Mukund (1999), p. 29–30

- Tansen Sen, Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, p.159

- Kulke & Rothermund (2001), p. 124

- Tripathi (1967), pp. 465, 477

- Sastri (1984), p. 604

- Tansen Sen, Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, p.156

- Kulke & Rothermund (2001), p. 117

- Thapar (1995), p. xv

- Mukund (2012), p. 92

- Mukund (2012), p. 95

- Lallanji Gopal, History of Agriculture in India, Up to c. 1200 A.D., p.501

- Tripathi (1967), p. 479

- Dehejia (1990), p. 10

- Harle (1994), p. 295

- Mitter (2001), p. 57

- V. V. Subba Reddy, Temples of South India, p.110

- Jermsawatdi (1979), p. 57

- John Stewart Bowman, Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, p.335

- Vasudevan (2003), pp. 21–24

- Nagasamy (1970)

- "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 186

- Mitter (2001), p. 163

- Thapar (1995), p. 309-310

- Wolpert (1999), p. 174

- Mitter (2001), p. 59

- Sanujit Ghose, Legend of Ram

- Ismail (1988), p. 1195

- D. P. Dubey, Rays and Ways of Indian Culture

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 116

- Sastri (2002), pp. 20, 340–341

- Sastri (2002), pp. 184, 340

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 20

- Encyclopaedia of Indian literature, vol. 1, p 307

- Spuler (1975), p. 194

- www.wisdomlib.org (23 June 2018). "The Telugu Cholas of Konidena (A.D. 1050-1300) [Part 1]". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Sastri (2002), pp. 342–343

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 115

- Sastri (1984), p. 681

- "Darasuram Temple Inscriptions". What Is India (2007-01-29). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- Tripathi (1967), p. 480

- Vasudevan (2003), p. 102

- Sastri (1984), p. 214

- Majumdar (1987), p. 4067

- Stein (1998), p. 134

- Vasudevan (2003), p. 104

- Natarajan, B.; Ramachandran, Balasubrahmanyan (1994). Tillai and Nataraja. Chidambaram, India: Mudgala Trust. p. 108.

- V. N. Hari Rao (1961). Kōil Ol̤ugu: The Chronicle of the Srirangam Temple with Historical Notes. Rochouse. p. 87.

- Kōvintacāmi, Mu (1977). A Survey of the Sources for the History of Tamil Literature. Annamalai University. p. 161.

- Sreenivasa Ayyangar, C. R. (1908). The Life and Teachings of Sri Ramanujacharya. R. Venkateshwar. p. 239.

- Mackenzie, Colin (1972). T. V. Mahalingam (ed.). Mackenzie manuscripts; summaries of the historical manuscripts in the Mackenzie collection. Vol. 1. University of Madras. p. 14.

- Jagannathan, Sarojini (1994). Impact of Śrī Rāmānujāçārya on Temple Worship. Nag. p. 148.

- Kalidos, Raju (1976). History and Culture of the Tamils: From Prehistoric Times to the President's Rule. Vijay. p. 139.

- Sastri (2002), p. 176

- Sastri (1984), p. 645

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 126

Works cited

- Barua, Pradeep (2005), The State at War in South Asia, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-80321-344-9

- Chopra, P. N.; Ravindran, T. K.; Subrahmanian, N. (2003), History of South India: Ancient, Medieval and Modern, S. Chand & Company Ltd, ISBN 978-81-219-0153-6

- Das, Sisir Kumar (1995), History of Indian Literature (1911–1956): Struggle for Freedom – Triumph and Tragedy, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-81-7201-798-9

- Dehejia, Vidya (1990), The Art of the Imperial Cholas, Columbia University Press

- Devare, Hema (2009), "Cultural Implications of the Chola Maritime Fabric Trade with Southeast Asia", in Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay (eds.), Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-9-81230-937-2

- Eraly, Abraham (2011), The First Spring: The Golden Age of India, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-67008-478-4

- Gough, Kathleen (2008), Rural Society in Southeast India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52104-019-8

- Harle, J. C. (1994), The art and architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2004), "From Differences to Ethnic Solidarity Among the Tamils", in Hasbullah, S. H.; Morrison, Barrie M. (eds.), Sri Lankan Society in an Era of Globalization: Struggling To Create A New Social Order, SAGE, ISBN 978-8-13210-320-2

- Ismail, M. M. (1988), "Epic - Tamil", Encyclopaedia of Indian literature, vol. 2, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 81-260-1194-7

- Jermsawatdi, Promsak (1979), Thai Art with Indian Influences, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-8-17017-090-7

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2001), A History of India, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0

- Keay, John (12 April 2011), India: A History, Open Road + Grove/Atlantic, ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0

- Lucassen, Jan; Lucassen, Leo (2014), Globalising Migration History: The Eurasian Experience, BRILL, ISBN 978-9-00427-136-4

- Majumdar, R. C. (1987) [1952], Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4

- Miksic, John N. (2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300_1800. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-558-3.

- Mitter, Partha (2001), Indian art, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-284221-3

- Mukherjee, Rila (2011), Pelagic Passageways: The Northern Bay of Bengal Before Colonialism, Primus Books, ISBN 978-9-38060-720-7

- Mukund, Kanakalatha (1999), The Trading World of the Tamil Merchant: Evolution of Merchant Capitalism in the Coromandel, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-8-12501-661-8

- Mukund, Kanakalatha (2012), Merchants of Tamilakam: Pioneers of International Trade, Penguin Books India, ISBN 978-0-67008-521-7

- Nagasamy, R. (1970), Gangaikondacholapuram, State Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamil Nadu

- Nagasamy, R. (1981), Tamil Coins – A study, Institute of Epigraphy, Tamil Nadu State Dept. of Archaeology

- Paine, Lincoln (2014), The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World, Atlantic Books, ISBN 978-1-78239-357-3

- Prasad, G. Durga (1988), History of the Andhras up to 1565 A. D., P. G. Publishers

- Rajasuriar, G. K. (1998), The history of the Tamils and the Sinhalese of Sri Lanka

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007), Historical Dictionary of the Tamils, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-81086-445-0

- Rothermund, Dietmar (1993), An Economic History of India: From Pre-colonial Times to 1991 (Reprinted ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-41508-871-8

- Sadarangani, Neeti M. (2004), Bhakti Poetry in Medieval India: Its Inception, Cultural Encounter and Impact, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 978-8-17625-436-6

- Sakhuja, Vijay; Sakhuja, Sangeeta (2009), "Rajendra Chola I's Naval Expedition to South-East Asia: A Nautical Perspective", in Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay (eds.), Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-9-81230-937-2

- Sastri, K. A. N. (1984) [1935], The CōĻas, University of Madras

- Sastri, K. A. N. (2002) [1955], A History of South India: From Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar, Oxford University Press

- Scharfe, Hartmut (2002), Education in Ancient India, Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-12556-8

- Schmidt, Karl J. (1995), An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0-76563-757-4

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999), Ancient Indian History and Civilization, New Age International, ISBN 978-8-12241-198-0

- Sen, Tansen (2009), "The Military Campaigns of Rajendra Chola and the Chola-Srivija-China Triangle", in Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay (eds.), Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-9-81230-937-2

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-8-13171-120-0

- "South Indian Inscriptions", Archaeological Survey of India, What Is India Publishers (P) Ltd, retrieved 30 May 2008

- Spuler, Bertold (1975), Handbook of Oriental Studies, Part 2, BRILL, ISBN 978-9-00404-190-5

- Stein, Burton (1980), Peasant state and society in medieval South India, Oxford University Press

- Stein, Burton (1998), A history of India, Blackwell Publishers, ISBN 978-0-631-20546-3

- Subbarayalu, Y. (2009), "A Note on the Navy of the Chola State", in Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay (eds.), Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-9-81230-937-2

- Thapar, Romila (1995), Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History, South Asia Books, ISBN 978-81-7154-556-8

- Tripathi, Rama Sankar (1967), History of Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2

- Talbot, Austin Cynthia (2001), Pre-colonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19803-123-9

- Vasudevan, Geeta (2003), Royal Temple of Rajaraja: An Instrument of Imperial Cola Power, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-383-0

- Wolpert, Stanley A (1999), India, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22172-7

Further reading

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1955). A History of South India, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002).

- Durga Prasad, History of the Andhras up to 1565 A. D., P. G. PUBLISHERS

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1935). The Cōlas, University of Madras, Madras (Reprinted 1984).