Megaliths in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

In the area of present-day Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany, up to 5,000 megalith tombs were erected as burial sites by people of the Neolithic Funnelbeaker (TRB) culture. More than 1,000 of them are preserved today and protected by law. Though varying in style and age, megalith structures are common in Western Europe, with those in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern belonging to the youngest and easternmost—further east, in the modern West Pomeranian Voivodeship of Poland, monuments erected by the TRB people did not include lithic structures, while they do in the south (Brandenburg), west (Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein) and north (Denmark).

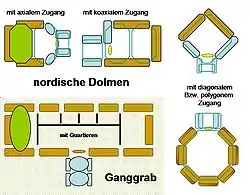

Though megaliths are distributed throughout the state, their structure differs between regions. Most megaliths are dolmens, often located within a circular or trapezoid frame of singular standing stones. Locally, the dolmens are known as Hünengräber ("giants' tombs") or Großsteingräber ("large stone tombs"), their framework is known as Hünenbett ("giants' bed") if trapezoid or Bannkreis ("spellbind circle") if circular.

The materials used for their construction are glacial erratics and red sandstones. 144 tombs have been excavated since 1945. The megaliths were used not only by the bearers of the TRB culture, but also by their successors, and have entered local folklore.

Origin

The megaliths in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern were erected as burial sites in the Neolithic, by the bearers of the Funnelbeaker (TRB) culture,[1][2] between 3,500 and 3,200 BC.[3] Initially, the TRB people buried their dead in pits, often covered with mounds of clay.[2] Later, they erected dolmens for this purpose,[2] but also continued the use of flat graves.[1] All megaliths were erected during a relatively short time period, spanning about 200 years or about seven generations, with the oldest ones dating to phase C of the Early Neolithic, while most were built in the beginning of the Middle Neolithic.[1]

The dolmens were built from glacial erratics, with the gaps filled with red sandstone.[4] Presumably, standing stones were transported to the site using rollers, slides, levers and ropes, and the interior of the unfinished dolmens was filled with clay to form a ramp to enable the movement of the cover stones into their final position.[4] After removing the clay from the interior, a barrow (tumulus) was then raised on top of the dolmen, which remained accessible through a passage made from smaller stones.[4] In addition, single standing stones were sometimes placed around the dolmen, forming either a rectangular or trapezoidal shape (Hünenbett),[4] or a stone circle (Bannkreis).[5] Sometimes, large singular "guardian stones" (Wächterstein, Bautastein) were placed adjacent to these shapes.[5] The interior of the dolmen was usually divided into small compartments by slabs of red sandstone, standing upright.[4]

Numbers and types

The various types of megalithic monuments in northeastern Germany were last compiled by Ewald Schuldt in the course of a project to excavate megalithic tombs from the Neolithic Era, which was conducted between 1964 and 1972 in the area of the northern districts of East Germany. His aim was to provide a "classification and naming of the objects present in this field of research".[6] In doing so it utilised a classification by Ernst Sprockhoff, which in turn was based on an older Danish model.[7]

Naming scheme

Schuldt listed six types:

- the simple dolmen (Urdolmen)

- the extended dolmen (erweiterte Dolmen)

- the great dolmen (Großdolmen)

- the passage grave (Ganggrab)

- the long barrow without a chamber (Hünenbett ohne Kammer)

- the stone cist (Steinkiste)

Sites

Schuldt (1972) described 1048 megalithic sites in the area of present-day Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.[1] Holtorf (2000/08) counted 1,193 in the same area.[1] Both Schuldt's and Holtorf's counts include 31 long mounds without chambers and 44 stone cists, which lack the large stones typical of the rest of the megalithic sites.[1] Holtorf estimated that in the Neolithic, up to 5,000 megalithic monuments were built in present-day Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.[1] 144 megaliths have been excavated since 1945.[1] 106 of these were excavated and afterwards restored by archaeologist Ewald Schuldt and his team between 1964 and 1972.[8]

Though megalithic sites can be found in nearly all areas of Mecklenburg-Vorpomern, Schuldt (1972) defined nine high-density areas: near Grevesmühlen (Forst Everstorf), near Rerik, along the middle and upper Warnow river, around the lakes of Krakower See and Plauer See, along the Recknitz river, along the Schwinge stream, and the southeastern part of the island of Rügen.[1]

The type of megalithic structures varies between different, overlapping regions.[1] Schuldt classified those regions as follows: He found long mounds without chambers in the southwestern part of Mecklenburg, passage graves in the northern and central part of Mecklenburg, extended dolmens in southern Mecklenburg, great dolmens with 'draught excluders' (Windfang) in northern Vorpommern, great dolmens with ante-chambers (Vorraum) in central Vorpommern, and stone cists in southern Vorpommern and eastern Mecklenburg.[1][9]

While the orientation of the megaliths varies, many have entrances facing southwards.[1] Of 99 dolmens studied by Schuldt, 46 are oriented toward the midsummer apex of the sun (south to north), 26 toward the spring equinox (east to west), 14 toward the midsummer sunrise (northeast to southwest), and 13 toward the midwinter sunrise (southeast to northwest).[10]

Primary and secondary uses

Disarticulated bones from up to twenty individuals have been discovered in excavated dolmens.[1] Presumably, the dead were first laid down in the open, and their bones were buried in the dolmens once the body was skeletonized.[4] Few dolmens contain only TRB finds, as most were also used by the contemporary and subsequent Globular Amphora and Single Grave cultures,[1] and some remained in use until the Bronze Age.[1][4] The bearers of the Globular Amphora culture removed and demolished skeletons and items from previous burials before reusing the tombs for their own dead.[1] When the tombs ceased to function as burial sites for the TRB and Globular Amphora cultures, they were filled with earth, with the exception of some tombs on Rügen where items from Bronze Age burials were found on the ground of the Neolithic chamber, or within the fill.[11]

Often, the earth-filled megaliths and the mounds raised to cover them were used for secondary burials.[11] The bearers of the Neolithic Single Grave culture buried their dead in the earth-filled chamber by removing cover or wall stones.[1][11] Of documented later secondary burials, 27% are from the late Bronze Age, 29% from the pre-Roman Iron Age, 10% from the Roman Iron Age and 27% from the Slavic period.[11] Another 7% are of uncertain origin, and no secondary burials from the early German period are recorded.[11] According to Holtorf, the barrows erected for burials in the Bronze Age, Iron Age and Slavic period were imitations of the mounds elevated above filled megalith tombs.[12] Some Neolithic mounds containing secondary burials are found next to similar burial mounds from the respective later period.[12]

In addition to secondary burials, other items were found in 41 of the 144 excavated megalith mounds.[13] Also, items from later periods were found outside of 75 of those megaliths, within a radius of no more than 500 metres (550 yd).[14] The attribution of all documented finds to their respective periods of origin is shown in the table below.

| Archaeological finds younger than Early Bronze Age in and near megalith mounds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late Bronze Age | Pre-Roman Iron Age | Roman Iron Age | Slavic period | Early German period | uncertain | |

| Finds from within megalith mounds (including secondary burials) |

16%[13] | 26%[13] | 8%[13] | 31%[13] | 16%[13] | 3%[13] |

| Finds near megalith mounds (within a radius of no more than 500 m) |

10%[14] | 17%[14] | 19%[14] | 35%[14] | 18%[14] | 1%[14] |

Some megaliths have cup-marks (Näpfchen) on them, which Holtorf describes as "simple, roughly hemispherical depressions of about 2–10 cm diameter and up to 3 cm depth."[15] The origin and purpose of the cup-marks is uncertain.[15] Their distribution corresponds with the distribution of the dolmens, and they are found on undisturbed dolmens as well as stones derived from destroyed megalith sites.[15]

Preservation

Many megaliths were used as quarries in the past, e.g. for the construction of 13th- and 14th-century churches, medieval and early modern stone walls, 18th-century manor houses, as well as for 19th-century dikes, roads, bridges and milestones.[16] Others were destroyed in the course of clearing farmland, which occurred from the 18th through 20th centuries.[17]

On 13 April 1804, Frederick Francis I, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg issued a decree protecting "heathen grave sites" and called on his officials to compile lists of the megaliths in their districts.[18] This was the earliest such decree in Germany.[18] In the following centuries, this decree was renewed and amended by Friedrich Franz's successors.[18] In Vorpommern, despite the authorities not issuing similar decrees, the University of Greifswald did decree preservation of megaliths on its property.[18] In 1946, all megalithic sites became the property of the East German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.[18] In 1954, the East German regime passed a preservation law which also applied to megaliths.[18]

On 30 November 1993, the currently binding preservation law was enacted by the re-constituted state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Gesetz zum Schutz und zur Pflege der Denkmale im Lande Mecklenburg–Vorpommern, "Law for the Protection and the Care of Monuments in the State of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern").[18]

Lore

Megaliths in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern are the subject of an abundance of lore, dealing primarily with giants, fairies, dwarfs, subterraneans and hidden treasures.[19] The giant tales relate primarily to the megaliths' creation, which was assumed to be the result of stones lost or thrown by giants, or of giants building houses, ovens or tombs.[19] Thus, the population refers to dolmens as Hünengräber ("giants' tombs", Sg. Hünengrab).[19][20]

Another frequent theme of megalith-related folklore is that of hidden treasures, guarded by fairies, dwarfs or subterraneans.[19][20] In these tales, humans who try to retrieve the treasure are usually hindered or punished by the magic beings.[19] The treasure tales have contributed both to long-time preservation of megaliths and to tomb raiding, depending on the degree of superstition of the audience.[19]

List of megalithic sites

See also

Sources

- References

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 1.1.

- Kehnscherper (1983), p. 127

- Schirren (2009), p. 60

- LAKD MV: Großsteingräber.

- Kehnscherper (1983), p. 130

- Schuldt 1972, p. 13

- Ernst Sprockhoff: Die nordische Megalithkultur, 1938, cited in Schuldt 1972, p. 10

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 1.3.1.

- Kehnscherper (1983), pp. 136-137

- Kehnscherper (1983), pp. 167-168

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 5.1.1.

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 5.1.6.

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 5.1.2.

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 5.1.3.

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 5.1.7.

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 5.2.5.

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 5.2.6.

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 1.3.2.

- Holtorf (2000-2008), 5.2.7.

- Schmidt (2001), p. 10

- Bibliography

- Holtorf, Cornelius (2000-2008): Monumental Past. The Life-histories of Megalithic Monuments in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Germany). Electronic monograph. University of Toronto. Centre for Instructional Technology Development. http://hdl.handle.net/1807/245. Retrieved 29 August 2010. Chapters referenced:

- 1.1. Megaliths in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 1.3.1. Ewald Schuldt (1914–1987). Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 1.3.2. Monument protection in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 5.1.1. Secondary burials in the mounds of megaliths. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 5.1.2. Later finds in the mounds of megaliths. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 5.1.3. Later finds near the mounds of megaliths. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 5.1.6. Imitations of ancient burial mounds. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 5.1.7. Cup-marks on megaliths.

- 5.2.5. Re-using the stones of megaliths. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 5.2.6. Destruction of megaliths for clearing fields and land. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- 5.2.7. The folklore of megaliths. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- Kehnscherper, Günther (1983). Hünengrab und Bannkreis (in German). Urania.

- LAKD MV (Landesamt für Kultur und Denkmalpflege Mecklenburg-Vorpommern): Großsteingräber. Meisterwerke steinzeitlicher Architektur. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- Schirren, C. Michael (2009). "Für die Ewigkeit gebaut – Die Großsteingräber". Archäologische Entdeckungen in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Kulturlandschaft zwischen Recknitz und Oderhaff. Archäologie in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in German). Vol. 5. Schwerin. pp. 57–61. ISBN 978-3-935770-24-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schmidt, Ingrid (2001). Hünengrab und Opferstein. Bodendenkmale auf der Insel Rügen (in German). Rostock: Hinstorff. ISBN 3-356-00917-6.

- Further reading

- Schuldt, Ewald (1972): Die mecklenburgischen Megalithgräber. Untersuchungen zu ihrer Architektur und Funktion. in: Beiträge zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte der Bezirke Rostock, Schwerin und Neubrandenburg, vol. 6. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften.

- Sprockhoff, Ernst (1938/1967): Atlas der Megalithgräber, Teil 2: Mecklenburg, Brandenburg und Pommern.

External links

Media related to Megaliths in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Megaliths in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern at Wikimedia Commons- Cornelius Holtorf's database of megaliths in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and northern Brandenburg

- (in German) Thomas "Stollentroll" Witzke's database of dolmens in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

- (in German) Dolmens in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (grosssteingraeber.de)

- (in German) Megalith monuments in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (huenengraeber.de)