Meissen porcelain

Meissen porcelain or Meissen china was the first European hard-paste porcelain. Early experiments were done in 1708 by Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus. After his death that October, Johann Friedrich Böttger continued von Tschirnhaus's work and brought this type of porcelain to the market, financed by Augustus the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony. The production of porcelain in the royal factory at Meissen, near Dresden, started in 1710 and attracted artists and artisans to establish, arguably, the most famous porcelain manufacturer known throughout the world. Its signature logo, the crossed swords, was introduced in 1720 to protect its production; the mark of the swords is reportedly one of the oldest trademarks in existence.

Dresden porcelain (or "china") was once the usual term for these wares, until in 1975 the Oberlandesgericht (Higher Munich State Court) decided in favour of the Saxon Porcelain Manufactory Dresden, which alone was then allowed to use the name Dresden Porcelain (it ceased producing in 2020).[1]

.jpg.webp)

Meissen remained the dominant European porcelain factory, and the leader of stylistic innovation, until somewhat overtaken by the new styles introduced by the French Sèvres factory in the 1760s, but has remained a leading factory to the present day. Among the developments pioneered by Meissen are the porcelain figurines, and the introduction of European decorative styles to replace the imitation of Asian decoration of its earliest wares.

Since 1991, the manufactory has been operating as the Staatliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Meissen GmbH,[2] whose owner is the Free State of Saxony. The company is one of the world's leading porcelain manufacturers and one of the oldest and most internationally known German luxury brands.[3]

Beginnings

Chinese porcelain had gradually developed over centuries, and by the seventeenth century both Chinese and Japanese export porcelain were imported to Europe on a large scale by the Dutch East India Company and its equivalents in other countries. It was a very expensive product by the time it reached European customers, and represented wealth, importance and refined taste in Europe. European attempts to produce porcelain, such as the brief experiment that produced Medici porcelain in Florence, had met with failure.[4]

At the beginning of the eighteenth century Johann Friedrich Böttger pretended he had solved the dream of the alchemists, to produce gold from worthless materials. When King Augustus II of Poland heard of it, he kept him in protective custody and requested him to produce gold. For years Johann Friedrich Böttger was unsuccessful in this effort.

At the same time, Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, a mathematician and scientist, experimented with the manufacture of glass, trying to make porcelain as well. Crucially, his ingredients included kaolin, the vital ingredient of true porcelain, though he was unable to use it successfully.[5] Tschirnhaus supervised Böttger and by 1707 Böttger reluctantly started to help in the experiments by Tschirnhaus.

When Tschirnhaus suddenly died, the recipe apparently was handed over to Böttger, who within one week announced to the King that he could make porcelain. Böttger refined the formula and with some Dutch co-workers, experienced in firing and painting tiles, the stage was set for the manufacturing of porcelain. In 1709, the King established the Royal-Polish and Electoral-Saxon Porcelain Manufactory (Königlich-Polnische und Kurfürstlich-Sächsische Porzellan-Manufaktur),[6] placed Böttger's laboratory at Albrechtsburg castle in Meissen and production started officially in 1710.

Early work

The first type of ware produced by Böttger was a refined and extremely hard red stoneware known as "Böttger ware" in English (in German: Böttgersteinzeug). This copied Chinese Yixing ware, and like that was especially used for teapots, and now coffee pots. Similar wares had been made by the Dutch and the Elers brothers in England. Böttger's version was harder than any of these,[7] and retained very crisp definition in its cast or applied ("sprigged") details, on bodies that could be polished to a gloss before firing. Models were derived from Baroque silver shapes and Chinese ceramic examples. There was also a softer stoneware, which was glazed and decorated.[8] Meissen's production of a hard paste white porcelain that could be glazed and painted soon followed, and wares were put on the market in 1713.

Böttger's experimental wares rapidly gained quality but never achieved successful painted and fired decor. The first successful ornaments were gold decorations applied upon the fired body and finely engraved before they received a second firing at a lower temperature. The lacy frameworks outside painted scenes known in German as Laub- und bandelwerk in red, gold or puce, were often used.[9] Augustus II charged first Johann Jakob Irminger with the design of new vessels. In 1720 Johann Gregor Herold became the director and in 1723 introduced brilliant overglaze colours that made Meissen porcelain famous, with an increasingly broad palette of colors that marked the beginning of the classic phase of Meissen porcelain. His enamel paints are still the basis for ceramic paints today. Initially painting mostly imitated the oriental designs known from Chinese and Japanese export porcelain, but some European landscape scenes were painted from early on.[10]

The signature underglaze "Meissen Blue" was introduced by Friedrich August Köttig. Soon minutely detailed landscapes and port scenes, animals, flowers, galante courtly scenes and chinoiseries, fanciful Chinese-inspired decorations, were to be found on Meissen porcelain. The Kakiemon floral decoration of vases and tea wares in Japanese export porcelain were combined with Chinese famille verte to create a style known as Indianische Blume ("Indian Flowers"); Augustus had large collections of both Chinese and Japanese porcelain. Coloured grounds with decoration painted on white in panels appear in the 1730s.[11] Paintings by Watteau were copied. Wares were also sold with plain glazed colors, usually white, to be enamelled in private workshops (Hausmalerei), many in Augsburg and Bayreuth, and independently retailed.[12] The support of Augustus' patronage attracted to Meissen some of the finest painters and modellers of Europe as staff artists.

- Up to 1725

Böttger stoneware coffeepot, c. 1710-13

Böttger stoneware coffeepot, c. 1710-13 Böttger stoneware figure of Augustus the Strong, c. 1713

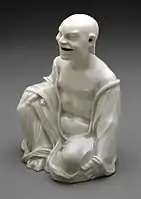

Böttger stoneware figure of Augustus the Strong, c. 1713 Oriental figure, c. 1715

Oriental figure, c. 1715 Teapot, 1718–20, with "Oriental" flowers

Teapot, 1718–20, with "Oriental" flowers_MET_DP155994.jpg.webp) One of a pair of vases, 1720–25

One of a pair of vases, 1720–25_MET_DP149937_(cropped).jpg.webp) Wine pot in the shape of a peach, c. 1725

Wine pot in the shape of a peach, c. 1725.jpg.webp) Teapot, Circa 1724-25, Walters Art Museum

Teapot, Circa 1724-25, Walters Art Museum Sake bottle vase, painted by Johann Gregor Herold, 1725

Sake bottle vase, painted by Johann Gregor Herold, 1725

Famous trademark

The Albrechtsburg was utilized to protect the secrets of the manufacture of the white gold. As a further precaution, very few workers knew the arcanum (hidden, secret knowledge) of how to make porcelain, and then perhaps only part of the process. Thus, for a few years, Meissen retained its monopoly on the production of hard-paste porcelain in Europe. By 1717, however, a competing production was set up at Vienna, as Samuel Stöltzel, head of the craftsmen and arcanist at Meissen, sold the secret recipe, which involved the use of kaolin, also known as china clay. By 1760 about thirty porcelain manufacturers were operating in Europe, most of them, however, producing frit based soft-paste porcelain.

In order to identify the original Meissen products, Meissen developed markings that initially were painted on, but were soon fired in underglaze blue. Early markings such as AR (Augustus Rex, the monogram of the King), K.P.M. (Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur), M.P.M. (Meissener Porzellan-Manufaktur), and K.P.F. (Königliche Porzellan-Fabrik) were eventually replaced by the crossed swords logo, based on the arms of the Elector of Saxony as Arch-Marshal of the Holy Roman Empire. Introduced in 1720, the logo was used consistently after 1731 by official decree. Variations in the logo allow approximate dating of the wares. However, in the 18th century, the mark was not considered important, and it was commonly painted on in a crude manner. It wasn't until the "dot period" when a gentleman asked that the mark be adjusted to look older that the factory got serious about mark control.

Artistic development

.jpg.webp)

_MET_DP108438.jpg.webp)

After Irminger, the next chief modeller, Johann Jakob Kirchner, was the first to make large-scale statues and figurines, especially of Baroque saints. His assistant was Johann Joachim Kaendler; in 1733 Kirchner resigned, and Kaendler took over as chief modeller, remaining in place until his death in 1775, and becoming the most famous of the Meissen modellers. Under his direction Meissen produced the series of small figurines, which brought out the best of the new material (see below).[13] His menagerie of large-scale animals, left in the white, are some of the high points of European porcelain manufacture. His work resulted in the production of exquisite figurines in the rococo style that influenced porcelain making in all of Europe. He was supported by assistants like Johann Friedrich Eberlein and Peter Reinecke.

In 1756, during the Seven Years' War, Prussian troops occupied Meissen, giving Frederick II of Prussia the opportunity to relocate some of the artisans to establish the Royal Porcelain Manufacture Berlin (Königliche Porzellan Manufaktur Berlin; KPMB). With the changing tastes of the neoclassical period and the rise of Sèvres porcelain in the 1760s, Meissen had to readjust its production, and in the reorganization from 1763, C.W.E. Dietrich of the Dresden Academy became artistic director and Michel-Victor Acier from France became the modelmaster. The practice of impressing numerals that correspond to moulds in the inventory books began in 1763.

Marcolini period

Count Camillo Marcolini ran the factory from 1774 to 1813, when after the Battle of Leipzig he followed Frederick Augustus I of Saxony into exile, dying in Prague the next year. This period's output was marked by Sèvres styles and ventures into Neoclassicism, such as unglazed matte biscuit porcelain wares that had the effect of white marble. Meissen wares were slightly reduced in quality, and considerably in quantity during this period, as both Austria and Prussia banned imports, and Britain, France and Russia placed high tariffs on imports - all now had their own industries to protect.[14]

19th-century

In the nineteenth century Ernst August Leuteritz modernized many of the rococo figurines, and reissued them, creating a "Second Rococo" characterized by lacework details (made from actual lace dipped in slip and fired) and applied flowers. One of the flower painters was Georg Friedrich Kersting. After about 1830 the fortunes of the factory revived, although with wares that appeal less to modern taste than the 18th-century ones. The factory had great commercial success with the lithophane technique, introduced in 1829, which produced a picture when held up to the light.[15]

20th-century

Under Erich Hösel, who became head of the modelling department in 1903, old styles were revived and reinterpreted. Hösel also restored eighteenth century models. Some appealing work in the Art Nouveau style was produced, but Meissen's mainstay continued to be the constant production of revived eighteenth-century models.

After 1933, the artistic freedom of the artists became restricted by the State of Saxony in accordance with the contemporary indoctrination process in Germany. Some artists (i.e. Ernst Barlach) who had contributed to progressive Meissen during the Weimar period were banned.

After World War II and under Communist rule, the manufactory that had always catered to the rich and wealthy had some difficulty to find its way. The danger was that Meissen would become a factory merely producing for the masses. It was not until 1969, when Karl Petermann became the director, that Meissen went back to focus on its old traditions and was also allowed a freer artistic expression.

Figures

Figurines had been produced under Böttger, when a small white figure of Augustus II the Strong was produced. Johann Joachim Kändler modelled many of the most famous figures, which were initially made for decorating the tables at grand meals, usually in white, replacing sugar sculptures. However, they soon became very popular as ornaments for living rooms and were cheaper than an entire table service, so available to a rather wider market, both in terms of geography and social class. Kändler soon had them brightly painted, increasing their attraction.

Human figures were mostly courtiers, shepherds and shepherdesses (Dresden shepherdess is a proverbial term), commedia dell'arte characters, animals, personifications or "allegorical figures" (such the seasons, virtues, or continents) and figures in Chinese and Turkish costumes. As well as the pastoral fantasy shepherdesses there were also some more realistic figures of urban workers, based on print series of the street cries of Paris, London and other cities. In the 1750s a large series of miners was produced. The Meissen repertoire had a huge influence on other European porcelain factories, and the porcelain figure is a defining object for the Rococo.[16]

Kändler also produced a modello of Augustus III of Poland on a horse which was intended to be a life size statue for the city. There is an all white figure of the Triumph of Amphitrite in Berlin that is the only known figure signed by Kändler.[17]

A famous large group, or menagerie, of animal figures were ordered by Augustus for the Japanese Palace he was building in the 1720s. Kändler took the series over in 1733, and modelled most of the figures. These were often many times the size of most figures, and making them posed great technical problems. Nonetheless, when seen as a group they were a sight that astonished and impressed visitors.[18] Smaller figures of animals, especially birds, were also very popular.

The "Monkey Band" (German: Affenkapelle, lit. '"ape orchestra"'), are a comic group of figures of monkey musicians, and a larger excited conductor, all in fancy contemporary costumes. They were first modelled by Kändler and Reinicke in 1753-54, with a later set in the 1760s. They were copied by Chelsea porcelain and others.[19] Such singerie were popular in various media.

Large goat for the menagerie of the Japanese Palace, 1732

Large goat for the menagerie of the Japanese Palace, 1732 The conductor from the "Monkey Band", 1760s version.

The conductor from the "Monkey Band", 1760s version. Pantalone with an actress, Johann Joachim Kaendler, c. 1741

Pantalone with an actress, Johann Joachim Kaendler, c. 1741_MET_ES1927.jpg.webp) Pair of golden orioles, 1740–41

Pair of golden orioles, 1740–41 Le Marquis, from the Cris de Paris series, Circa 1757, Private Collection.

Le Marquis, from the Cris de Paris series, Circa 1757, Private Collection. Dancing Harlequine, from the Duke of Weissenfels series, Circa 1747, Private Collection.

Dancing Harlequine, from the Duke of Weissenfels series, Circa 1747, Private Collection. Apollo and the Muses, centrepiece, c. 1750

Apollo and the Muses, centrepiece, c. 1750%252C_Johann_Joachim_Kaendler_and_assistants%252C_Meissen_Porcelain_Factory%252C_c._1760%252C_hard-paste_porcelain_-_Wadsworth_Atheneum_-_Hartford%252C_CT_-_DSC05370.jpg.webp) Asia from a set of the Four Continents, modelled by Kaendler, c. 1760

Asia from a set of the Four Continents, modelled by Kaendler, c. 1760.jpg.webp) Candelabrum, one of a pair, 1760s

Candelabrum, one of a pair, 1760s Figurines by Jacob Ungerer: Gardener Girl with Dog, Goose Girl, Lady with Cat, 1902.

Figurines by Jacob Ungerer: Gardener Girl with Dog, Goose Girl, Lady with Cat, 1902.

Tableware patterns

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Böttger early foresaw the production of tableware, and the first services were made in the 1720s. Initial services were plain, but Kaendler soon introduced matching decorations. Kaendler also produced the 1745 "New Cutout" pattern, characterized by a wavy edge cut, and is presumed to have designed the much-copied osier pattern of a relief border imitating a woven wicker or osier fence.

Initially relatively small tea and coffee services were the most produced, but from the 1730s large armorial porcelain dinner services began to be made, initially for Augustus, but then other buyers in Germany and abroad.[20] They also became used for diplomatic gifts. Maria Amalia of Saxony, granddaughter of Augustus, married the King of the Three Sicilies, later Charles III of Spain, and her dowry is said to have included 17 Meissen table services, inspiring the couple to found the Capodimonte porcelain factoruy in Naples.[21]

The most famous of these is the Swan Service (Schwanenservice) made in 1737-1743, for the manufactory's director, Count Heinrich von Brühl;[22][23] It eventually numbered more than a thousand pieces. At the end of World War II, the pieces of the Swan Service were scattered amongst collectors and museums. Yet, with the moulds still available, the pattern continues to be made today. The Möllendorff Dinner Service of the 1760s is another huge service, also today divided between many collections.

The Blue Onion pattern (in fact copying Chinese pomegranates) has been in production for close to three centuries. It was effectively designed by Höroldt in 1739 and is probably inspired by a Chinese bowl from the Kangxi period. Widely popular, the pattern has been copied extensively by over sixty companies; some of those competitors have even used the word Meissen as a marking. But the pattern became so popular and widespread that the German Supreme Court in 1926 ruled that the Meissen Zwiebelmuster was in the public domain.

A series of "Court Dragon" and "Red Dragon" tableware patterns features Chinese dragons, generally in underglaze red with gilt details flying around the rim of the plate and with a medallion in the center of the cavetto. A version of this pattern was used in Hitler's Kehlsteinhaus retreat.

Other popular patterns still in production include the Purple Rose pattern and the Vine-leaf pattern.

Hard-porcelain plate with Chinese dragons, Circa 1734, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

Hard-porcelain plate with Chinese dragons, Circa 1734, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. Plate c. 1740

Plate c. 1740 Dish from a tea-service, c. 1740

Dish from a tea-service, c. 1740 Two "osier pattern" dishes of the first "Sulkowski" type, 1755–60

Two "osier pattern" dishes of the first "Sulkowski" type, 1755–60 Blaue Rispe pattern, from 1903, by Richard Riemerschmid

Blaue Rispe pattern, from 1903, by Richard Riemerschmid

Ownership

At the beginning the Meissen manufactory was owned by the King of Saxony; by 1830 it came to belong to the State of Saxony. After World War II, most of the equipment was sent to the Soviet Union as part of war reparations. However, the workers using traditional methods and the kilns that had not been dismantled were able to resume production by 1946. The company became a Soviet Joint Stock Company in Germany. Almost all of the production was sent to the Soviet Union, a crucial step that kept the artisan community alive. After the establishment of the German Democratic Republic, the company was handed over to German ownership in 1950 and became a Volkseigener Betrieb (VEB), a "people-owned company". VEB Meissen Porzellan turned out to be one of the few profitable companies in the economically troubled East German system, earning much needed foreign currency. After the German reunification in 1990, the company was restored to the State of Saxony which is the sole owner. While its products are expensive, the high quality and artistic value make Meissen porcelain desirable by collectors and connoisseurs.

Meissen collections

The rarity and expense of Meissen porcelain meant that originally it could be bought only by the upper classes; this gradually changed over the 19th century. When a wealthy class emerged in the United States in the nineteenth century, such families as the Vanderbilts started their own collections. Many of these collections then found their way into the world's great museums, including the Dixon Gallery and Gardens, featuring one of the largest collections in America.[24]

A collection of 117 chinoiserie items, including a mantel clock case made for Augustus the Strong dated 1727, which had been assembled by Dr Franz Oppenheimer and his wife, Margarethe, was auctioned by Sotheby's in September 2021.[25][26]

A Meissen porcelain chocolate pot, cover, and stand, dated c.1780, were amongst the wedding gifts of Queen Elizabeth II.[27]

Personalities

- Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, inventor of Meissen porcelain

- Johann Friedrich Böttger, introduced manufacturing process of Meissen porcelain

- Heinrich Gottlieb Kühn, introduced the colouring process

- Friedrich August Köttig, introduced the Meissen Blue

- Johann Joachim Kaendler, master modeller ca. 1730-1770[28]

- Johann Eleazar Zeissig, known as Schenau, painter, designer and Director of the drawing school at the porcelain factory from 1773.

Gallery

Vase, c. 1730, in Indianische Blume ("Indian flowers") imitating the Kakiemon style of Arita porcelain, Japan.

Vase, c. 1730, in Indianische Blume ("Indian flowers") imitating the Kakiemon style of Arita porcelain, Japan..jpg.webp) Man seated on plinth, holding monkey and ball. Meissen factory. Dated circa 1735. British Museum

Man seated on plinth, holding monkey and ball. Meissen factory. Dated circa 1735. British Museum.jpg.webp) Produced around 1818 in the Wedgwood style, this allowed the Meissen company to compete with its English counterparts, Birmingham Museum of Art.

Produced around 1818 in the Wedgwood style, this allowed the Meissen company to compete with its English counterparts, Birmingham Museum of Art. Ebonized vitrine featuring hand painted Dresden(not Meissen as previously mentioned) porcelain mounts, Circa 1870.

Ebonized vitrine featuring hand painted Dresden(not Meissen as previously mentioned) porcelain mounts, Circa 1870. Rococo Porcelain 12-Light Chandelier, Circa 1900.

Rococo Porcelain 12-Light Chandelier, Circa 1900. Candelabrum for the Aleksander Józef Sułkowski service by Johann Joachim Kaendler, Circa 1736, Dallas Museum of Art

Candelabrum for the Aleksander Józef Sułkowski service by Johann Joachim Kaendler, Circa 1736, Dallas Museum of Art Clock with birds by Johann Joachim Kaendler, Circa 1746

Clock with birds by Johann Joachim Kaendler, Circa 1746 Central medallion of a Meissen plate, 19th century.

Central medallion of a Meissen plate, 19th century. Four Elements Porcelain Ewers by Meissen, 18th century.

Four Elements Porcelain Ewers by Meissen, 18th century. Autumn and Summer Porcelain Urns by Meissen, 1880.

Autumn and Summer Porcelain Urns by Meissen, 1880.

Notes

- Oberlandesgericht München, Verdict 10 July 1975, Case number 6 U 5307/74.

- "Porcelain Manufactory MEISSEN".

- Florian Langenscheidt, Bernd Venohr (Hrsg.): Lexikon der deutschen Weltmarktführer. Die Königsklasse deutscher Unternehmen in Wort und Bild. Deutsche Standards Editionen, Köln 2010, ISBN 978-3-86936-221-2.

- Battie, 86-87

- Battie, 88

- "Meissen porcelain". (dead Link)

- Battie, 88

- Battie, 88

- Battie, 89

- Battie, 89

- Battie, 89

- Battie, 93-94

- Greenberger, Michael (2019). Early Meissen Porcelain: The Michael Greenberger Collection.

- Battie, 158-159

- Battie, 159-160

- Battie, 91-92

- Honey, W. B. (1934). Dresden China: An Introduction to the Study of Meissen Porcelain.

- Battie, 91

- Battie, 91-92

- Battie, 90

- Le Corbellier, 20

- Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art : guide to the collection. [Birmingham, Ala]: Birmingham Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- Battie, 90

- Meissen Encyclopaedia Archived 2008-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Laurence Mitchell. Accessed December 2006

- "Porcelain seized by Nazis goes up for auction in New York". The Guardian. 29 August 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- "Sotheby's to sell $2m Meissen porcelain collection restituted by Dutch government to heirs of Jewish industrialist". The Art Newspaper. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- "Royal Collection". Archived from the original on March 30, 2014.

- Greenberger, Michael (2019). Early Meissen Porcelain: The Michael Greenberger Collection.

References

- Battie, David, ed., Sotheby's Concise Encyclopedia of Porcelain, 1990, Conran Octopus, ISBN 1850292515

- Le Corbellier, Clare, Eighteenth-century Italian porcelain, 1985, Metropolitan Museum of Art, (fully available online as PDF)

- Ducret, S. German Porcelain and Faience. 1962.

- Greenberger, Michael. Early Meissen Porcelain: The Michael Greenberger Collection. New York, NY, 2019.

- Roentgen, R.E.: The Book of Meissen. Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA, USA 2nd edition, 1996.

- Rückert, R. Meissner Porzellan 1710-1820. 1966.

- Walcha, O. Meissner Porzellan 1975.

- Walcha, O.; Helmut Reibig [editor], "Meissen Porcelain." G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1981.

.jpg.webp)