Menispermaceae

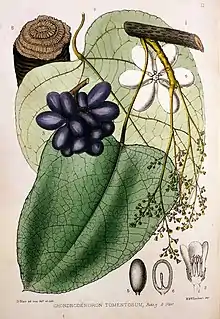

Menispermaceae (botanical Latin: 'moonseed family' from Greek mene 'crescent moon' and sperma 'seed') is a family of flowering plants. The alkaloid tubocurarine, a neuromuscular blocker and the active ingredient in the 'tube curare' form of the dart poison curare, is derived from the South American liana Chondrodendron tomentosum. Several other South American genera belonging to the family have been used to prepare the 'pot' and 'calabash' forms of curare. The family contains 68 genera with some 440 species,[3] which are distributed throughout low-lying tropical areas with some species present in temperate and arid regions.

| Menispermaceae Temporal range: [1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Menispermum canadense | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Ranunculales |

| Family: | Menispermaceae Juss.[2] |

| Genera | |

| |

Description

- Twining woody climbing plants, winding anti-clockwise (Stephania winds clockwise) or vines, rarely upright shrubs or small trees, more rarely still herbaceous plants or epiphytes (Stephania cyanantha), perennial or deciduous, with simple to uni-serrate hairs.

- Alternate spiral leaves, simple, whole, dentate, lobed to palmatifid (bi- o trifoliate in Burasaia), frequently peltate, petiolated, petiole frequently pulvinate at both extremes, without stipules, sometimes with spines derived from the petioles (Antizoma), venation, parallelodromous, penninerved or frequently palmatinerved, bifacial, rarely isofacial, in Angelisia and Anamirta with hydathodes derived from trichomes, domatia present in 5 genera as pits or hair tufts. Various types of stomata, frequently cyclocytic.

- Rapidly growing stems with trilacunar nodes. Phylloclades are present in Cocculus balfourii.

- Dioecious plants, sometimes perfect flowers in Tiliacora acuminata and Parabaena denudata.

- Inflorescences in racemiform, paniculate or thyrse with partial inflorescences in a capituliform cyme or pseudo-umbel, multifloral, rarely single or paired flowers, axillary or on sharp branches or cauliflorous trunks, females frequently less branched.

- Flowers small, regular to zygomorphic (Antizoma, Cyclea, Cissampelos), cyclic to irregularly spiral, hypogynous, basically trimers. Receptacle sometimes with developed gynophore. Sepals (1-)3-12 or more, usually in (1-)2(-many) whorls of 3, rarely 6, free to slightly fused, imbricate or valvate, sometimes less numerous in female flowers. Petals 0–6, in 2 whorls of 3, rarely of 6, free or fused, frequently holding the opposite stamen, sometimes less numerous in female flowers. Androecium of (1-)3-6(-40) stamens free of the perianth, free or fused together in 2–5, fasciculate or monadelphous, introrse, dehiscence along longitudinal, oblique or transversal slits. Female flowers sometimes with staminodes. Gynoecium apocarpous, superior, of (1-)3-6(-32) carpels, usually oppositipetalous, stigma apical, dry, papillous, ovules 2 per carpel, anatropous, hemianatropous to campilotropous, uni- or bitegmic, crassinucellate, the superior epitropous and fertile, the inferior apotropous and abortive, placentation marginal ventral. Male flowers sometimes with carpelodes.

- Fruit compound, each unit in a straight or flattened, asymmetric drupe, more or less stipitate (rarely only one developed), not coalescing, exocarp sub-coriaceous or membranous, mesocarp pulpy, fleshy or fibrous, endocarp woody to petrous, rough, tuberous, echinate or ribbed, often with a recess in the placenta called a condyle.

- Seeds slightly curved or spiral (Limaciopsis, Spirospermum), with endosperm absent or present, totally or only ventrally ruminate or not ruminate, oleaginous, embryo straight or curved, with two cotyledons flat or cylindrical, leafy or fleshy, divaricate or applied.

- Pollen tricolpate, without operculum nor ribs, tectum perreticulate columellate, endexine granular; or the pollen can be colporate (Abuta), syncolporate (Tinospora), pororate or hexa-cryptoporate (with 6 apertures).

- Chromosomal number: x = 11, 13, 19, 25. 2n can be up to 52.

Ecology

It is thought that the cauliflorous species are pollinated by small bees, beetles or flies although there are no direct observations of this. Birds disperse the purple or black drupes, for example Sayornis phoebe (a tyrant flycatcher) eats the fruit of Cocculus. In Tinospora cordifolia a lapse of 6–8 weeks has been observed between fertilization and the first zygotic cell division.

The menispermaceae predominantly inhabit low altitude tropical forests (up to 2,100m), where they are climbers, but some genera and species have adapted to arid locations (Antizoma species have adapted to the South African deserts or Cocculus balfouri and its phylloclades have adapted to the climate on the island of Socotra) and other temperate climates. C3 photosynthesis has been recorded in Menispermum.

Phytochemistry

The family contains a wide range of benzylisoquinoline compounds (alkaloids) and lignans such as furofuran, flavones and flavonols and some proanthocyanidins. The most notable are the wide variety of alkaloids derived from benzyltetrahydroisoquinoline and aporphine, which accumulate as dimers, as well as the alkaloids derived from morphinan and from hasubanan and other diverse types of alkaloid such as derivative of aza-fluoranthene. Sesquiterpenes such as picrotoxin and diterpenes such as clerodane diterpene are also present, while the triterpenes are scarce and where present are similar to oleanane. Ecdysone steroids have also been found. Some species are cyanogenic.

Uses

The Menispermaceae have been used in traditional pharmacopeia and drugs have been formulated from these plants that are of great use in modern medicine. These drugs are based on alkaloids and include tubocurarine from curare, a poison used by indigenous South American tribes on their poison darts, that is obtained from species of Curarea, Chondrodendron, Sciadotenia and Telitoxicum. A similar poison was used in Asia (ipos) that was obtained from species of Anamirta, Tinospora, Coscinium and Cocculus. Tubocurarine and its synthetic derivatives are used to relax muscles during surgical interventions. The roots of "kalumba" or "colombo" (Jateorhiza palmata) are used in Africa for stomach problems and against dysentery. Species of Tinospora are used in Asia as antipyretics, the fruit of Anamirta cocculus is used to poison fish and birds and the stems of Fibraurea are used to dye fabric yellow. The South East Asian species Coscinium fenestratum, a local Thai remedy for stomach ailments ( which contains berberine and related alkaloids ) was recently implicated in mass harvesting operations to prepare extracts usable as precursors in the manufacture of the drug MDMA.[4]

Fossil record

The Middle Cretaceous genus Callicrypta from Siberia has been placed into Menispermaceae.[1] The Paleocene fossil record for the family includes at least 11 genera identified from compression leaf fossils found in Alaska and 15 genera and approximately 22 different Menispermaceae species identified from the Early Eocene London Clay. The London Clay genera Eohypserpa and Tinomiscoidea named by Reid & Chandler (1933) from mineralized nuts and an additional three genera Atriaecarpum, Davisicarpum, and Palaeosinomenium were later described by Chandler (1961, 1978). Additional species from those genera were identified in the Clarno nut beds by Scott and Manchester respectively.[5]

Menispermaceae is one of the most diverse families found in the Middle Eocene Clarno nut beds of central Oregon. Species belonging to thirteen different genera, most extinct, have been described based on cast or permineralized fruit and nut fossils from the beds, and four different foliage types are known from associated compression fossils. Chandlera and Odontocaryoideae were described by Scott (1954), while Manchester (1994) described Curvitinospora and Thanikaimonia.[5]

Phylogeny and internal classification

The APG IV system (2016; unchanged from the prior systems of 1998, 2003, and 2009) recognizes this family and places it with the eudicots order Ranunculales. Their trimerous flower structure is similar to the Lardizabalaceae and Berberidaceae, although they differ from them in other important characteristics. The APW (Angiosperm Phylogeny Website) considers that they form part of the Order Ranunculales, and that they are a sister group on the branch formed by the Lardizabalaceae and Berberidaceae families in a reasonably advanced clade of the order.[6] Kinship with the Berberidaceae is further borne out by similarities in phytochemistry e.g. in the presence of berberine and related alkaloids. It is a medium-sized family of 70 genera totaling 420 extant species,[6] mostly of climbing plants. The great majority of the genera are tropical, but with a few (notably Menispermum and Cocculus) reaching temperate climates in eastern North America and eastern Asia.

The genetic factors within Menispermaceae are very narrow resulting in many genera with one or a few species. According to Kessler (1993)[7] There wasn't sufficient data from genetic studies to evaluate subfamily and tribal division into five tribes (see Kessler, 1993, in the References section). As such division was fundamentally based on morphologic characteristics of the seeds with doubts as to whether the tribes are monophyletic. Further molecular research compiled and conducted by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group has clarified many of the interrelationships of the family.[6]

Chasmantheroideae

Burasaieae

- Aspidocarya J. D. Hooker & Thomson

- Borismene Barneby

- Burasaia Thouars

- Calycocarpum Torrey & A. Gray

- Chasmanthera Hochst.

- †Chandlera Scott[5]

- Chlaenandra Miquel

- Dialytheca Exell & Mendonça

- Dioscoreophyllum Engler

- Diploclisia Miers

- Disciphania Eichler

- Fawcettia F. Mueller

- Fibraurea Loureiro

- Hyalosepalum Troupin

- Jateorhiza Miers

- Kolobopetalum Engler

- Leptoterantha Troupin

- Odontocarya Miers (including Synandropus)

- Orthogynium Baillon

- Parabaena Miers

- Paratinosopora Wei Wang

- Penianthus Miers

- Platytinospora (Engler) Diels

- Rhigiocarya Miers

- Sarcolophium Troupin

- Sphenocentrum Pierre

- Syntriandrium Engler

- Tinomiscium J. D. Hooker & Thomson

- Tinospora Miers

Coscinieae

- Anamirta Colebrooke

- Arcangelisia Beccari

- Coscinium Colebrooke

Menispermoideae

Anomospermeae

- Abuta Aublet

- Anomospermum Miers (including Orthomene)

- Caryomene Barneby & Krukoff

- Diploclisia Miers

- Echinostephia (Diels) Domin [8]

- Elephantomene Barneby & Krukoff (including Cionomene)

- Elissarrhena Miers

- Hypserpa Miers

- Legnephora Miers

- Parapachygone Forman

- Pericampylus Miers

- Rupertiella Wei Wang & R. Ortiz

- Sarcopetalum F. Mueller

- Telitoxicum Moldenke

Cissampelidae

- Antizoma Miers

- Cissampelos L.

- Cyclea Wight

- Perichasma Miers

- Stephania Loureiro

Limacieae

- Limacia Loureiro

Menispermeae

- Menispermum L.

- Sinomenium Diels

Pachygoneae

- Cocculus de Candolle

- Haematocarpus Miers

- Hyperbaena Bentham

- Pachygone Miers

Spirospermeae

- Limaciopsis Engler

- Rhaptonema Miers

- Spirospermum Thouars

- Strychnopsis Baillon

Tiliacoreae

- Albertisia Beccari

- Anisocycla Baillon

- Beirnaertia Troupin

- Carronia F. Mueller

- Chondrodendron Ruiz & Pavón[9]

- Curarea Barneby & Krukoff

- Eleutharrhena Forman

- Macrococculus Beccari

- Pleogyne Miers

- Pycnarrhena J. D. Hooker & Thomson

- Sciadotenia Miers

- Synclisia Bentham & J. D. Hooker

- Syrrheonema Miers

- Tiliacora Colebrooke

- Triclisia Bentham & J. D. Hooker

- Ungulipetalum Moldenke

Incertae sedis

- †Callicrypta

Gallery

Menispermum canadense (Canada moonseed) : ripe fruit and crescent moon-shaped seeds.

Menispermum canadense (Canada moonseed) : ripe fruit and crescent moon-shaped seeds.

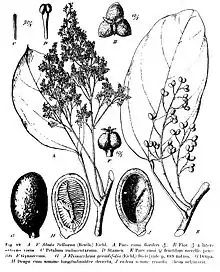

The Abuta species A. selloana : line drawing from Engler's Das Pflanzenreich.

The Abuta species A. selloana : line drawing from Engler's Das Pflanzenreich.

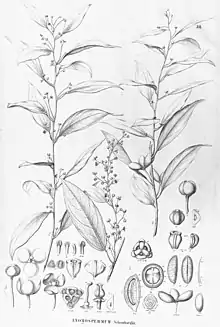

Anamirta cocculus : illustration from Köhler's Medizinal Pflanzen.

Anamirta cocculus : illustration from Köhler's Medizinal Pflanzen. Anomospermum : A. schomburgkii : anatomical study from the Flora Brasiliensis of von Martius and Eichler.

Anomospermum : A. schomburgkii : anatomical study from the Flora Brasiliensis of von Martius and Eichler. Cissampelos pareira: illustration from Blanco's Flora de Filipinas.

Cissampelos pareira: illustration from Blanco's Flora de Filipinas.

The Stephania species S. venosa in flower, Gothenburg Botanical Garden.

The Stephania species S. venosa in flower, Gothenburg Botanical Garden._Spreng.jpg.webp) Thai villagers harvesting large, medicinal root tuber of Stephania venosa.

Thai villagers harvesting large, medicinal root tuber of Stephania venosa. Stephania japonica in fruit, Mc.Kay Reserve, NSW, Australia.

Stephania japonica in fruit, Mc.Kay Reserve, NSW, Australia. Jateorhiza palmata illustration from Köhler's Medizinal Pflanzen.

Jateorhiza palmata illustration from Köhler's Medizinal Pflanzen. Foliage of Tinospora cordifolia.

Foliage of Tinospora cordifolia.

References

- Krassilov, Valentin; Golovneva, L.B. (2004). "A minute mid-Cretaceous flower from Siberia and implications for the problem of basal angiosperms". Geodiversitas. 26: 5–15.

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2009). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III" (PDF). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (2): 105–121. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Christenhusz, M. J. M. & Byng, J. W. (2016). "The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase". Phytotaxa. 261 (3): 201–217. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1.

- See the documentary film: "Death in the Forest". Speculation on the potential drug use of yellow vine. https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=fMXgaMwEejo Retrieved 11.42 on 10/11/18

- Manchester, S.R. (1994). "Fruits and Seeds of the Middle Eocene Nut Beds Flora, Clarno Formation, Oregon". Palaeontographica Americana. 58: 30–31.

- Stevens, P.F. (2015) [1st. Pub. 2001], Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, retrieved 28 January 2021

- Kessler, P.J.A. (1993). "Menispermaceae.". In Kubitzki, K.; Rohwer, J.G.; Bittrich, V. (eds.). The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. II. Flowering Plants - Dicotyledons. Springer-Verlag: Berlín. ISBN 978-3-540-55509-4.

- Jacques, Frédéric M.B.; Gallut, Cyril; Vignes-Lebbe, Régine; Zaragüeta i Bagils, René (2007):Resolving phylogenetic reconstruction in Menispermaceae (Ranunculales) using fossils and a novel statistical test. Taxon 56(2):379-392.

- RODRIGUES, Eliana; CARLINI, Elisaldo L. de Araújo. Plants with possible psychoactive actions used by the Krahô Indians, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria 28(4): 277- 82, 2006.

- Watson, L. & Dallwitz, M.J. (1992). "The families of flowering plants: descriptions, illustrations, identification, and information retrieval. Version: 29th July 2006". Archived from the original on 3 January 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2006.

External links

Media related to Menispermaceae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Menispermaceae at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Menispermaceae at Wikispecies

Data related to Menispermaceae at Wikispecies- links at CSDL

- Menispermaceae of Mongolia in FloraGREIF

- Map