Military history of Croatia

The military history of Croatia encompasses wars, battles and all military actions fought on the territory of modern Croatia and the military history of the Croat people regardless of political geography.

Medieval Croatian states

Croatian principalities

The first mention of Croatian military actions dates from the time of the Croatian principalities in the 8th and 9th centuries. Vojnomir led a Croatian army in wars against the Avars at the end of the 8th century. He launched a joint counterattack with the help of Frankish troops under Charlemagne in 791. The offensive was successful and the Avars were driven out of what then became Lower Pannonia under Frankish overlords. In 819, his successor Duke Ljudevit Posavski raised a rebellion against the Franks. Ljudevit won many battles against the Franks, but in 822 his forces were defeated. Prince Borna of Croatia led the army of Dalmatian Croatia and had a primary role in crushing Ljudevit's rebellion. Borna reported his successes to the Frankish Emperor, stating that Ljudevit had lost over 3,000 soldiers and 300 horses during his campaign. Prince Trpimir I of Croatia battled successfully against his neighbours, the Byzantine coastal cities under the strategos of Zadar in 846–848. In 853 he repulsed an attack from an Army of the Bulgarian Khan Boris I and concluded a peace treaty with him, exchanging gifts. Prince Domagoj of Croatia is known in the history for his navy which helped the Franks to conquer Bari from the Arabs in 871. During Domagoj's reign piracy was a common practice, which earned him a title of The worst duke of Slavs (Latin: pessimus dux Sclavorum). One of the strongest Croatian princes was Branimir, whose naval fleet defeated the Venetian navy on 18 September 887.

Kingdom of Croatia

First Croatian king Tomislav defeated the Magyar mounted invasions of the Arpads in battle and forced them across the Drava River. In 927 Tomislav's army heavily defeated the army of Bulgarian Emperor Simeon, under the command of general Alogobotur in the Battle of the Bosnian Highlands. One of Tomislav's admirals lead more than 5,000 sailors, soldiers and their families into Slavic quarter of Palermo, Sicily. At the peak of his reign, according to Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos' De Administrando Imperio, written around 950, Tomislav could raise a vast military force composed out of 100,000 infantrymen and 60,000 horsemen and a sizable fleet of 80 large ships and 100 smaller vessels. According to the palaeographic analysis of the original manuscript of De Administrando Imperio, the estimation of the number of inhabitants in medieval Croatia between 440 and 880 thousand people, and military numbers of Franks and Byzantines - the Croatian military force was most probably composed of 20,000-100,000 infantrymen, and 3,000-24,000 horsemen organized in 60 allagions.[1][2] but these numbers are generally taken as a considerable exaggeration.[3]

King Dmitar Zvonimir of Croatia took the hard line against the Byzantine Empire and joined the Normans in wars against Byzantium. When Robert Guiscard, Duke of Apulia, invaded the western Balkan provinces of the empire in 1084, Zvonimir sent troops to his aid.

King Petar Snačić's troops maintained resistance against repelling Hungarian assaults at Mount Gvozd in the war for the succession of the Croatian throne. At the end, the last native Croatian king was defeated and killed by King Coloman of Hungary in the Battle of Gvozd Mountain (1097).

Notable wars and battles of early and high medieval times

Notable wars and battles that included Croatian army:

- Battle of Gvozd Mountain (1097)

- Siege of Zadar (1202) – part of Fourth Crusade

- Fifth Crusade (1213–1221)

- Battle of Klis Fortress (1242) – part of Mongol invasion of Europe

- Battle of Grobnik field (1242)

- Zadar-Venice War (1311-1312)

- Battle of Bliska (1322)

- Louis I of Hungary's Dalmatian Campaign

- Battle of Samobor (1441)

Croatian medieval military organization

Croatian medieval military organization was based on Hungarian banderial system. This kind of organization was mentioned for the first time in 1260.[4] In the aftermath of 1491 Peace of Pressburg, Croatian feudal magnates such as Frankopans, or Counts of Krbava were permitted by the king to hold 400 strong banderium (with previous figure being 500 men), consisting out of 200 heavy cavalry and 200 light cavalry. In case of necessity, rest of the nobility had to equip and mobilize one soldier for each 20 serfs they owned, while ten members of lower nobility had to mobilize one horseman and place them under the banderium of their local county (županija).[5] Ban of Croatia was obliged to have 1000 strong banderium.[4]

Croatian-Ottoman Wars (15th–18th centuries)

Early confrontations

Hundred Years' Croatian–Ottoman War

- Battle of Krbava field (1493)

- Battle of Dubica (1513)

- Siege of Klis (1524)

- Siege of Jajce (1524)

- Battle of Mohács (1526)

- Battle of Belaj (1528)

- Hungarian campaign of 1527–1528

- Balkan campaign of 1529

- Siege of Vienna (1529)[6]

- Little War in Hungary (1530 – c.1552)

- Siege of Varaždin (1527)

- Siege of Güns (1532)

- Katzianer's Campaign (1537)

- Battle of Szigetvár (1566)

- Siege of Gvozdansko (1577–1578)

- Battle of Slunj (1584)

- Battle of Brest (1592)

- Battle of Sisak (1593)

Long War (1593–1606)

- Siege of Petrinja (1594)

- Battle of Brest (1596)

Austro-Turkish War (1663–1664)

- First Battle of Novi Zrin (1663)

- Battle at Jurjeve Stijene (1663)

- Second Battle of Novi Zrin (1663)

- Nikola Zrinski's Winter Campaign (1664)

- Battle of Krapina (1664)

- Third Battle of Novi Zrin (1664)

- Battle of Saint Gotthard (1664)

Great Turkish War (1683–1699)

- Siege of Virovitica (1684)

- Osijek Campaign (1685)

- Siege of Buda (1686)

- Battle of Mohács (1687) - resulted in liberation of Osijek

- Battle of Požega (1688)

- Lika Campaign (1688)

- Siege of Knin (1688)

- Siege of Udbina Castle (1689)

- Battle of Velika Monastery (1690)

- Battle of Osijek (1690)

- Battle of Slankamen (1691)

- Siege of Bihać (1697)

- Battle of Zenta (1697)

Gallery of images from Croatian-Ottoman Wars

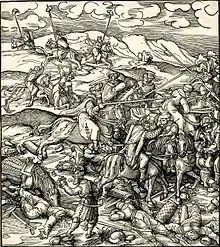

A depiction of Battle of Krbava Field between Croatians and Ottomans in 1493.

A depiction of Battle of Krbava Field between Croatians and Ottomans in 1493. Romanticized depiction of Nikola Šubić Zrinski's charge out of the fortress of Szigetvár during the Ottoman siege of the city in 1566. By J. P. Krafft.

Romanticized depiction of Nikola Šubić Zrinski's charge out of the fortress of Szigetvár during the Ottoman siege of the city in 1566. By J. P. Krafft..JPG.webp) Battle of Sisak in 1593.

Battle of Sisak in 1593. Nikola and Petar Zrinski burning Osijek bridge during Austro-Turkish War (1663–1664)

Nikola and Petar Zrinski burning Osijek bridge during Austro-Turkish War (1663–1664) A depiction of one of battles between Croats and Ottomans near Novi Zrin in 1664.

A depiction of one of battles between Croats and Ottomans near Novi Zrin in 1664.

Ottoman–Venetian War (1714–1718)

- Siege of Sinj (1715)

Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718)

- Battle of Petrovaradin (1716)

Austro-Turkish War (1788–1791)

Other wars of early modern period

- Siege of Sokolac (1493) - struggle between authority of Croatian ban and Anž Frankopan over control of Senj.

- First Revolt against Franjo Tahy

- Croatian-Slovene Peasant Revolt

- Battle of Krško

- Battle of Stubica

Early modern period Croatian military organization

The suppreme commander of Croatian Army was ban of Croatia. If necessary (due to his other duties), he had the option of appointing "Suppreme captain of the Kingdom".[7]

Croatian Sabor assembling in Križevci in 1538, drafted a law regarding military service of the peasantry. The law required for every feudal landlord in the Kingdom to provide one horseman from 36 serf houses on his estate.[7] This horseman had to be equipped with helmet, spear and shield and provided with salary throughout entire year.[7] These horsemen made part of the Frontier army. Sabor also had the option of hiring mercenaries.[7] In case of Ottoman raid on Croatian territory, alarm had to be raised by firing cannons or igniting bonfire.[7]

In wake of Hasan Pasha's Great Offensive on Croatia in 1592, Croatian sabor drafted a law on General Insurrection. The law required for all nobles, landlords and magnates to respond to mobilization personally. Each feudal landlord had to provide one well armed horseman from 10 houses on his estate and two riflemen. Lower nobility had to go to arms personally. Women were required to stay home nad pray. Each monastery had to provide at least 4 horsemen. Royal free cities had to mobilize all citizens, except for barbers (medics). The suppreme commander of insurrection army was Suppreme captain of the Kingdom. All commoners caught selling weapons to Turks were to be summarily executed, while nobility members caught selling weapons to Turks were to be trialed against and all their weapons would be confiscated.[8]

Early modern period Croatian military evolution

Croatian historian Tadija Smičiklas refers to Konstantin Mihailović, a 14th century Serb soldier turned Janissary in claiming that in mid 15th century, both Croatians and many European armies lagged behind Ottomans in the art of warfare, until in mid 16th century Croats adopted Ottoman style of warfare.[9] Both authors emphasized advantages of Ottoman light cavalry in comparrison with European heavy knights due to their superior mobility and visibility. Contrary to European knights, Ottomans preferred killing enemy's horse in order to immobilize the knight.[9] Croatians eventually also moved on from heavy medieval chivalry and accepted mobile Ottoman style of warfare which laid the foundation for Croatian light cavalry. Croatians also adopted raids into enemy territory as common element of warfare and started launching raids of their own against the Ottomans.[10]

Historic units and formations originating from the time of the Ottoman wars

19th century

At the beginning of the 19th century many Croatian troops (as a part of the Austrian imperial army) fought in the Napoleonic Wars against the French Grande Armée. Later, a significant Croatian force (four regiments) fought on the French side during Napoleon's invasion of Russia.[11]

At the end of the first half of the 19th century, following in the wake of the French revolution, Croatian romantic nationalism emerged to counteract the non-violent but apparent Germanization and Magyarization. By the 1840s, and during the revolutions of 1848, the movement had moved from cultural goals to resisting Hungarian political demands which grew even bigger during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. Croatian Ban Josip Jelačić cooperated with the Austrians in quenching the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 by leading a military campaign into Hungary.

Battles of the Hungarian Revolution involving Croats:

- Battle of Pákozd (1848)

- Vienna Uprising (1848)

- Battle of Schwechat (1848)

- Battle of Mór (1848)

Croatian troops also contributed in other conflicts which involved the Austrian Empire. According to the sources, out of 7,871 sailors on Austrian ships around 5,000 were Croats.[12] Many Croatian sailors fought on the Austrian side in 1866 during Third Italian War of Independence in the Battle of Vis.

The territory of Military Frontier - a buffer zone along Habsburg-Ottoman border taken from Croatia back in the 16th century due to the Croatian-Ottoman Wars was demilitarized and in July 1873 and united with civil Croatia in 1881.[13]

Formation of Royal Croatian Home Guard

After reaching Croatian-Hungarian Settlement of 1868, Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia gained limited authonomy in relation to Kingdom of Hungary.[15] The settlement was a legal basis for creation of Royal Croatian Home Guard, a special detachment of Hungarian Honved where Croatian symbols, Croatian oath of allegiance and Croatian command language were in use.[16] After restructuring of 1889-1899 Croatian Home Guard became part of the country's regular standing army.[16]

Standard weapon of 16th Croatian-Hungarian Infantry Regiment from Varaždin was 8mm Mannlicher M1895 bolt action rifle with bayonet.[17] Soldiers had both parade uniforms and campaign uniforms. The latter ones consisted of grayish trousers, blouse, cap and greatcoats for cold weather.[17]

When it comes to Hussar Home Guard Regiments, in 1914, they were armes with Mannlicher Cavalry Carabine and 87 cm long sabre.[17] Cavalrymen also wore a distinctive hat (chako) with Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen coat of armes, which includes Croatian, Dalmatian and Slavonian coat of arms and inscription written in Croatian: "for king and homeland" (Za kralja i domovinu).[17]

Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Croatian troops, including Home Guard units under command of baron Josip Filipović[19] took part in Austro-Hungarian campaign in Bosnia and Herzegovina of 1878.[15] In preparation for the Bosnia and Herzegovina campaign troops of 36th Division were additionally reinforced. 18th Split Infantry Division, commanded by Lieutenant field marshal Stjepan Jovanović participated in Austro Hungarian southern thrust into Herzegovina in August 1878.[20] The 18th made two pronged thrust into Bosnia and Herzegovina near Vrgorac and Imotski and pushed towards Ljubuški, with their ultimate objective being Mostar.[20] The 18th reached Mostar by 5 August and next day Jovanović established control over the city.[21] Croatian troops also took part in battles in Bosanska Krajina, during efforts to take Bihać.[22]

20th century

World War I

During World war I, Croat soldiers served in Royal Croatian Home Guard and other units. Some of notable Croatian commanders of that time were Field Marshal Svetozar Boroević, General Stjepan Sarkotić and Admiral Maximilian Njegovan.

Unlike the other fronts, Croats participating in World War I, were most motivated to fight on the Italian front, as Treaty of London (which brought Italy into World War I), promised large chunks of Croatian littoral to Italy.[23] Secondly, unlike the other fronts, on Italian front Croats did not have to fight their "slavic brothers".[23]

Notable battles of World War I that included Croatian troops:

- Serbian Campaign (World War I) (1914)

- Adriatic Campaign of World War I (1914–1918)

- Battle of Galicia (1914)

- Brusilov Offensive (1916)

- Battle of Soča (1915)

- Battle of Caporetto (1917)

- Bombardment of Ancona (1915)

- Battle of the Piave River (1918)

- Battle of Vittorio Veneto (1918)

Svetozar Boroević - Croatian field marshal, credited for repelling twelve Italian offensives[24] on Italian front, thus earning nickname a "Lion of Isonzo".[24][25]

Svetozar Boroević - Croatian field marshal, credited for repelling twelve Italian offensives[24] on Italian front, thus earning nickname a "Lion of Isonzo".[24][25]

Croatian Home Guard during WWI.

Croatian Home Guard during WWI. Croatian soldiers on Eastern Front in Galicia.

Croatian soldiers on Eastern Front in Galicia. An artillery battery manned by Croatians on Italian front.

An artillery battery manned by Croatians on Italian front.

The end of World War I was followed by the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and the formation of new national states. The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was formed from the southernmost parts of the Austria-Hungary but it lasted for only a month.

After it was clear that Austria-Hungary had lost World War I, the Austrian government decided to give much of the Austro-Hungarian Navy fleet, to the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. This move would have avoided handing the fleet to the Allies, since the new state had declared neutrality. Soon, the Fleet was attacked and dismembered by the Italian Regia Marina and the flagship SMS Viribus Unitis was sunk along with his captain and commander of Navy of the newly formed state, admiral Janko Vuković.

World War I aftermath

Interwar period

Throughout the interwar period, the Royal Yugoslav Army was mostly Serb dominated institution, which discouraged Croatians from joining it. Major issue was Serbian tradition of corporal punishment, which was unknown in former Austro-Hungarian lands and which caused much resistance when introduced.[26] Former Austro-Hungarian officers were ofter regarded as second-class officers, and often found themselves subordinated to much younger Serbs officers who were completely uneducated.[26] Croatian officers often felt offended for being attacked on national basis.[26] In certain cases, officers were put to jail for not knowing how to write in Serbian Cyrillic script.[26] This ethnic inequality in armed forces caused frequent desertions and occasional rebellions among Croatians in the army.[26] Prior to World War II out of 165 generals only two were Croats, two were Slovenes, the rest were Serbs.[27]

World War II

As Axis forces overran Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April War of 1941, Croatian fascists Ustaše under Gernan-Italian sponsorship arrived to Zagreb and proclaimed Independent State of Croatia (NDH).[28] Almost immediately, Ustaše started a campaign of mass terror (and genocide) against large Serb population in NDH, as well as Jews, Romani and anti-fascist Croats.[29] However, when Hitler started his Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, Croatian communists responded by launcing an uprising, thus giving Serbs of NDH a chance to escape the Ustaše persecution by joining their ranks. To great annoyance of Germans, Ustaše continued their persecution which made the uprising grow ever bigger,[30] forcing Germans to commit ever more tropps to quell it. While Serbs were forced to join communist People's Liberation Army of Yugoslavia (NOVJ) in order to save their lives,[31] Croatians as a nation were divided between those supporting Axis in order to preserve what they perceived as their new state and those opposing Ustaše. Yugoslav communists who opposed pre-war Serb domination, also offered a federalized state to the Croats, thus creating a platform acceptable to both Serbs and Croats.[32] However, when Ustaše gave away much of Dalmatia to Italian irredentists by agreeing to Treaties of Rome, their support among Croatians sank even lower, especially in Dalmatia which was given to Italy.[33] As Croatian historian Dušan Bilandžić points out; throughout World War II, Croats as a nation were engaged in several wars at once.[34] Firstly, they were engaged in a war against axis occupation.[34] Secondly, they were engaged in a civil war between those Croats who are anti-fascist and those who are pro-axis.[34] And thirdly, they were engaged in an inter-ethnic war between Croats and Serbs.[34]

In general, NDH units can be divided into two cattegories: firstly there were the Homeguards (Domobrani), which was a regular army of NDH consisting out of conscripted men with a low desire to fight. Besides them, there were also Ustaše militia (Ustaška vojnica) - an official paramilitary arm of Ustaša movement, virtually independent of regular army and mostly consisting of volunteers.[35] In 1942, Ustaše government sent a detachment of its units to fight along Axis forces in Battle of Stalingrad.[36]

Communist partisans continued to wage a guerilla war against Axis forces in the country. A major breaktrhough happened in September 1943, when fascist Italy capitulated which was a major impetus for Dalmatian Croats to join communist partisans as well as partisans who acquired large quantities of Italian weapon stocks.[37][38] That same year, partisan uprising spread among Croats in Istria, however Germans considered Istrian peninsula too important in case of spaculated Allied landing on Eastern Adriatic, so Erwin Rommel was sent to Istria and his forces quashed the uprising by brute force.[39]

Except for NOVJ and NDH loyal units, Greater Serbian Chetnik Royalist detachments also operated in the country committing massacres against non-Serb population.

As Allied forces prevailed over Axis, NOVJ became recognised as part of an Allied Coalition in Teheran conference of 1943. As ever more people joined their ranks, NOVJ guerilla warfare evolved into a full-fledged army – Jugoslavenska Armija (JA) by 1945. On the other hand, by 1944, NDH authorities were forced to merge their Ustaše militia with their regular Homeguard units into Croatian Armed Forces (HOS).[40] As war came to its end in Spring 1945, remnants of HOS units with Ustaša government pulled out towards the Austrian border to surrender to the Allies, however British who awaited them there insisted for HOS to surrender to JNA. After the surrender, the HOS members along with many civilians who accompanied them were massacred in Bleiburg rapatriations.[38]

Battles of World War II:

- Invasion of Yugoslavia (1941)

- Battle of Stalingrad (1942)

- Battle of Neretva (1943)

- Battle of Sutjeska (1943)

- Battle on Lijevča field (1945)

- Battle of Sarajevo (1945)

- Battle of Odžak (1945)

Partisan artillery during Battle of Knin in 1944.

Partisan artillery during Battle of Knin in 1944. Soldiers of 8th Dalmatian Shock Corps in 1945.

Soldiers of 8th Dalmatian Shock Corps in 1945. Tanks of Yugoslav 4th Army entering Trieste in 1945.

Tanks of Yugoslav 4th Army entering Trieste in 1945.

Ustaše militia, responsible for committing genocide over Serbs, Jews, Romani and Croatian anti-fascists.

Ustaše militia, responsible for committing genocide over Serbs, Jews, Romani and Croatian anti-fascists.

Cold War

- Trieste Crisis

- United Nations Emergency Force[41]

Croatian War of Independence

In 1991, as Croatia proclaimed its intependance, tensions between new Croatian government on one side and Croatian Serbs militia backed by Yugoslav federal army (JNA) on the other escalated into Croatian War of Independence. With Croatian Territorial Defense (TO) weapons being locked by the Federal Army, Croatia saw urgent need to form its own armed forces.[42] They did it by expanding its police force and then forming Croatian National Guard (ZNG) subordinated to newly formed Ministry of Defense.[43][44] In September 1991, Croatian National Guard and Police blocked Yugoslav Federal Army's barracks throughout Croatia and in Battle of Barracks successfully forced JNA to withdraw from most of Croatia. By doing this Croatians successfully managed to get their hands on heavy weapons and most of its TO arsenal, especially after the capture of Varaždin barracks.[45] In September 1991, Croatia also formed its general staff.[46] Croatian troops at a time despite being well motivated, were just a "loosely organized and hastily trained" light infantry force supported with limited number ot tanks and artillery.[46] On 3 November 1991 ZNG was formally renamed to Croatian Army (HV)[47]

Nonetheless, after successfully defending Croatia in 1991, Croatians continued to improve their army in following years by creating their own doctrine, military culture and professional troops with the main aim of retaking self proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina, a separatist proto-state.[48] In 1992, HV established officers school for platoon and company commanders, as well as command/staff school for staff officers and senior field commanders. This was all later unified as Petar Zrinski HV University.[48] In 1994, Croatian Army also established NCO school in Zadar for its all-professional Guards brigades[48] whose main purpose was cunducting offensive operations.[49] These brigades were as follows:

- 1st Guards Brigade - "The Tigers"

- 2nd Guards Brigade - "The Thunders"

- 3rd Guards Brigade - "The Martens"

- 4th Guards Brigade - "The Spiders"

- 5th Guards Brigade - "The Hawks"

- 9th Guards Brigade - "The Wolves"

- 7th Guards Brigade - "The Pumas"

In terms of equipment, the HV also acquired more heavy weapons such as: Argentinian CITER 155 mm field guns, Romanian APR-40 rocket launchers, 21 MiG 21 fighter jets and 8 Mi-24 Hind helicopter gunships.[50] Croatians also domestically produced their own UAVs (such as: MAH-1, MAH-2 and BL M-99 "Bojnik"), used for scouting enemy positions and guiding artillery fire.[51][52][53] These systems were put to use in military operations in late stages of the war.[52] According to the assessment of the CIA, based on HV performance in the late stages of Croatian War of Independence as well as Bosnian War - by the late 1995 - Croatian Army became "a premier military organization in the Balkans"; with "excellent staff planning and combined arms capabilities".[54]

Some of the battles of from Croatian War of Independence include:

- Operation Coast-91 (1991)

- Battle of the Dalmatian channels (1991)

- Battle of Vukovar (1991)

- Battle of the barracks (1991)

- Operation Otkos 10 (1991)

- Siege of Dubrovnik (1991)

- Operation Maslenica (1993)

- Operation Medak pocket (1993)

- Operation Flash (1995)

- Operation Storm (1995)

Special police troops of Croatian Ministry of Interior in Pakrac, in August 1991.

Special police troops of Croatian Ministry of Interior in Pakrac, in August 1991. Croatian soldiers engaging a Serb tank in 1992.

Croatian soldiers engaging a Serb tank in 1992. A Croatian trooper in 1992.

A Croatian trooper in 1992..jpg.webp) The unmanned flying vehicle M-99 "Bojnik", the kind of which Croatian Army used in late stages of Croatian War of Independence.[52]

The unmanned flying vehicle M-99 "Bojnik", the kind of which Croatian Army used in late stages of Croatian War of Independence.[52]

Bosnian War

In terms of Croatian involvement in Bosnian War, CIA claims that in 1992 Croatian strategy and policy towards Bosnia and Herzegovina was shaped by president Tuđman and so-called Herzegovina lobby's vision, who considered that Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot be preserved as a unified state.[55] Tuđman apparently considered Banovina Hrvatska as legitimate and desirable model of territorial defining of Croatia.[56]

As the war in Croatia entered a ceasefire phase in 1992, while the Bosnian War was only beginning, Zagreb sent shipments of weapons to Bosnian Croats and allowed Bosnian Croats serving in HV to bring their weapons home, where they helped forming the Bosnian Croat army Croatian Defense Council (HVO). In certain cases still nascent HVO forces were commanded and organized by HV officers for which CIA refers to them as HV/HVO.[55] Foreign Arabic mujahideen fighters (formerly participating in conflicts in Afghanistan and Pakistan) arrived to Bosnia and Herzegovina across Croatia in two waves.[57] The first wave of mujahedeens arrived throughout 1992. The second wave of mujahedeeds arrived in spring 1994 after cessation of hostilities in Croat-Bosniak War.[57]

During the 1994 and 1995 Croatia supplied Bosnian 5th Corps defending Bihać with ammunition and medical supplies by an airbridge across Serb held territory.[58][59] Altogether 101 helicopter flights were organised; out of which 91 ended successfully while 10 failed.[60] As Serb forces tightened their grip on Bihać, by the late 1994, Croatians assessed potential fall of enclave as a threat to its own strategic position and threatened to intervene in the matter.[61] Croatians feared that if Bihać falls the Serb forces engaged in the siege would be able to redeploy to wider Karlovac area, where territory of Croatia was only ten kilometers deep before Slovenian border.[62] In order to deter Serbs from further attacking Bihać, as well as to improve its own positions arount Knin, Croatians launched Operation Winter '94 in late 1994.[61] As situation for Bosniak Army deteriorated in relation to Bosnian Serbs, Bosniaks asked Croatia for urgent help in July 1995, which resulted in signing of Split Agreement between Croatian and Bosnian government and established alliance between Croats and Bosniaks in the Bosnian War.[59] CIA also assessed that Operation Storm as well as joint Croat/Bosniak offensives in autumn 1995, had greater influence than NATO's air campaign in bringing Bosnian Serbs to negotiating table which ended the Bosnian War.[63]

- Croat–Bosniak War (1992–1994)

- Operation Winter '94 (1994)

- Operation Summer '95 (1995)

- Operation Mistral 2 (1995)

- Operation Southern Move (1995)

HVO's T-55 tank.

HVO's T-55 tank.

21st Century

War in Afghanistan

Croatia sent its troops to Afghanistan for the first time in 2003. This initial Croatian contingent consisted of 50 personnel, most of whom then were military policemen. As the time passed the number of Croatian troops in Afghanistan increased, along with complicity of the tasks assigned to them. Croatian troops took over tasks of mentoring Afghan National Army members, mentoring of Afghan pilots and air force technicians as well as providing security for various people and objects.[64] In 2006, Croatian soldier Goran Špehar was wounded near Kandahar by an RPG round explosion.[65] Another Croatian soldier was wounded in 2009 during training activities.[65] On 24 July 2019, corporal Josip Briški of Croatian Special Forces Command was killed in a Taliban suicide attack. He was the only Croatian soldier killed in action during Croatian deployment in Afghanistan.[66] In 2020 president Zoran Milanović announced complete withdrawal from Afghanistan after initial Croatian deployment.[67] Last Croatian soldiers pulled out in September same year.[68]

Kosovo

.jpg.webp) Croatian soldiers working with their American and French counterparts in Afghanistan.

Croatian soldiers working with their American and French counterparts in Afghanistan..jpg.webp) Croatian troops during military exercise in 2012.

Croatian troops during military exercise in 2012. Croatian M-84 tanks on military parade in 2015.

Croatian M-84 tanks on military parade in 2015. Croatian Air Force and US Navy joint exercise in 2002.

Croatian Air Force and US Navy joint exercise in 2002.

See also

References

- Vedriš, Trpimir (2007). "Povodom novog tumačenja vijesti Konstantina VII. Porfirogeneta o snazi hrvatske vojske" [On the occasion of the new interpretation of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus'report concerning the strength of the Croatian army]. Historijski zbornik (in Croatian). 60: 1–33. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- Budak, Neven (2018). Hrvatska povijest od 550. do 1100 [Croatian history from 550 until 1100]. Leykam international. pp. 223–224. ISBN 978-953-340-061-7.

- John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 262

- "banderij | Hrvatska enciklopedija". www.enciklopedija.hr. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- Klaić, IV, 222-223

- "Zrinski, Nikola IV. | Hrvatska enciklopedija". www.enciklopedija.hr. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

Godine 1529. sudjelovao je u obrani Beča,

- Hartinger, Josip (1911). Hrvatsko-slovenska seljačka buna godine 1573 (in Croatian). Osijek: Tisak Julija Pfeiffera. pp. 72–73.

- Klaić, knjiga V, 472-473

- Smičiklas, Tadija (1882). Poviest hrvatska: dio 1 (in Croatian). Nakl. "Matice hrvatske". p. 642.

- 644

- Napoleon's Foreign Infantry

- The Battle of Vis, by Ante Sucur

- "Vojna krajina | Hrvatska enciklopedija". www.enciklopedija.hr. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- Mandić, Mihovil (1910). Povijest okupacije Bosne i Hercegovine. Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. p. 47.

Istom oko 2 sata popodne pogje za rukom pukovniku Hostineku, zapovjedniku 53. pjesac pukov te opkoli desno krilo ustaško i jurišem prisili na uzmicanje. Tom zgodom se odlikovaše Hrvati Leopoldovci.

- Macan, Trpimir (1995). Hrvatska povijest. Matica hrvatska. pp. 173–177. ISBN 953-150-030-4.

- "domobranstvo | Hrvatska enciklopedija". www.enciklopedija.hr. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "Hrvatski domobran: Kako je bio opremljen i naoružan". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- Mandić, 56-57

- "Hrvatski domobrani: Ova divizija postala je legendarna, a prozvali su je vražjom". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- Mandić, 35-40

- Mandić, 45-46

- Mandić, 86-88

- Oreskovich, John R. (27 August 2019). The History of Lika, Croatia: Land of War and Warriors. Lulu.com. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-359-86419-5.

- ""Hrvatski glavonja" Svetozar Borojević - Žuto-crni general". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- "Borojević od Bojne: zaboravljeni hrvatski ratni junak". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- Banac, Ivo (1988). Nacionalno pitanje u Jugoslaviji: porijeklo, povijest, politika. Ljubljana: Globus. pp. 146–148.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1969). Contemporary Yugoslavia; twenty years of Socialist experiment. Internet Archive. Berkeley : University of California Press. p. 11.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1969). "Yugoslavia During the Second World War". Contemporary Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Socialist Experiment: 78 – via Google Books.

- Tomasevich, 78

- Tomasevich, 79

- Tomasevich, 81

- Tomasevich, 84

- "Bitka na Sutjesci: Hrvatska bitka u kojoj je poginulo 3000 Dalmatinaca". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 28 February 2023.

Nasuprot raspravi o naravi Bitke na Sutjesci, povjesničari su suglasni da je to po nacionalnom i teritorijalnom sastavu partizanskih jedinica bila "hrvatska bitka", a Dalmatince je u partizane, kažu, otjerao teror talijanskih fašista.

- Bilandžić, Dušan (1999). Hrvatska moderna povijest. Zagreb: Golden Marketing. pp. 125–203.

- Alonso, Miguel; Kramer, Alan; Rodrigo, Javier; Kralj, Lovro (26 November 2019). "The Evolution of Ustasha Mass Violence". Fascist Warfare, 1922–1945: Aggression, Occupation, Annihilation. Springer Nature. p. 243. ISBN 978-3-030-27648-5.

- "Jutarnji list - Heroji za pogrešnu stvar: Bačeni na Staljingrad". www.jutarnji.hr (in Croatian). 24 February 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- Tomasevich, 102

- Tanner, Marcus (27 July 2010). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War; Third Edition. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17159-4.

- "Rommelov krvavi trag u Istri – DW – 09.01.2021". dw.com (in Croatian). Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- "Usudi li se itko u Hrvatskoj načeti 'ustaške mirovine'?". tportal.hr. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- "Srbija svojata hrvatske zasluge u misijama UN-a". Slobodna Dalmacija. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990-1995. Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis. 2002. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990-1995. Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis. 2002. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- "Jutarnji list - JELI SDP DOISTA RAZORUŽAO HRVATSKU, KAKO TO TVRDI MILIJAN BRKIĆ? Evo što je utvrdilo saborsko povjerenstvo. Koje je osnovao - HDZ..." www.jutarnji.hr (in Croatian). 6 October 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- CIA, 95

- CIA, 96

- "Povjesnica - Ministarstvo obrane RH". 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- CIA, 272

- CIA, 275

- CIA, 276

- "Pet oružja koja su Hrvatskoj donijela pobjedu u Oluji". tportal.hr. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- "Bojnik je uz pomoć kirurškog programa iz SAD-a slao snimke položaja protivnika!". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- "Specijalne jurišne puške i roboti za mine: Svjetski hitovi hrvatske vojne industrije". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- CIA, 392

- Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict. Vol. II. Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis. 2002. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

294-296

- Vidov, Petar (30 November 2017). "Činjenicama protiv histerije: Hrvatska je u BiH bila i agresor, a za to je kriv Franjo Tuđman". Faktograf.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- "Jutarnji list - Garibi: Islamski borci u Bosni za koje rat još nije završio". www.jutarnji.hr (in Croatian). 2 January 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- "Kako su Srbi srušili helikopter u kojemu je bila i pošiljka za Večernjak i zašto su prije Oluje ubijeni bošnjački ministar i hrvatski general". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- Prometej. "Hrvoje Klasić i Husnija Kamberović o ulozi Hrvatske u ratu u BiH". www.prometej.ba. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- "Dokumenti koji pokazuju kako je Armija BiH od Zagreba grozničavo tražila pomoć za Bihać". Jabuka.tv (in Croatian). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- CIA, Vol II, 534-543

- "Jutarnji list - GENERAL ĆOSIĆ: KAKO SMO PROMIJENILI TIJEK RATA U zadnji trenutak smo spasili Bihać i time spriječili novu Srebrenicu". www.jutarnji.hr (in Croatian). 4 August 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- CIA, Vol I, 391-396

- "Zadaće naših vojnika u Afganistanu sve zahtjevnije". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- Telegram.hr. "Dosad je u Afganistanu bilo 5374 naših vojnika, ovo je prvi put da je netko poginuo. No, bilo je slučajeva ranjavanja". Telegram.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- Hina. "Napad na vojnike u Afganistanu: Jedan vojnik stigao u Hrvatsku". Vijesti.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Ivanković, Davor. "Zbogom Afganistanu - pozdrav Kosovu". Večernji list. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "Jutarnji list - Posljednji hrvatski vojnici napustili misiju u Afganistanu: Sve je završilo spuštanjem zastave". www.jutarnji.hr (in Croatian). 12 September 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- Enciklopedija leksikografskog zavoda 1966–69 (in Croatian)

.svg.png.webp)

_(1868-1918).svg.png.webp)