Military mobilisation during the Hundred Days

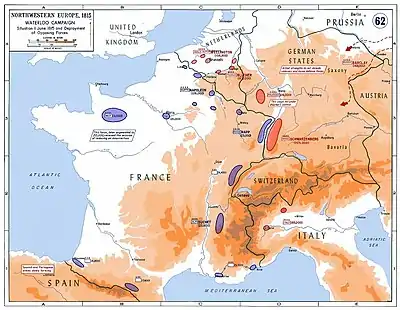

During the Hundred Days of 1815, both the Coalition nations and the First French Empire of Napoleon Bonaparte mobilised for war. This article describes the deployment of forces in early June 1815 just before the start of the Waterloo Campaign and the minor campaigns of 1815.

| Military mobilisation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Days | |||||

Strategic situation in Western Europe in June 1815 | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

Seventh Coalition: | ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

|

von Hake | ||||

French

Upon assumption of the throne, Napoleon found that he was left with little by the Bourbons and that the state of the Army was 56,000 troops of which 46,000 were ready to campaign.[1] By the end of May, the total armed forces available to Napoleon had reached 198,000 with 66,000 more in depots training up but not yet ready for deployment.[2]

Waterloo Campaign

By the end of May, Napoleon had deployed his forces as follows:[3]

- I Corps (D'Erlon) cantoned between Lille and Valenciennes.

- II Corps (Reille) cantoned between Valenciennes and Avesnes.

- III Corps (Vandamme) cantoned around Rocroi.

- IV Corps (Gerard) cantoned at Metz.

- VI Corps (Lobau) cantoned at Laon.

- Cavalry Reserve (Grouchy) cantoned at Guise.

- Imperial Guard (Mortier) at Paris.

The preceding corps were to be formed into L'Armée du Nord (the "Army of the North") and led by Napoleon Bonaparte would participate in the Waterloo Campaign.

Armies of observation

For the defence of France, Bonaparte deployed his remaining forces within France observing France's enemies, foreign and domestic, intending to delay the former and suppress the latter. By June, they were organised as follows:

V Corps – Armée du Rhin[4] (Rapp), cantoned near Strassburg.

- 15th Infantry Division (Commanded by General Rottembourg)[5]

- 16th Infantry Division (Commanded by General Albert)[5]

- 17th Infantry Division (Commanded by General Grandjean)[5]

- On 20 June 1815 Rapp's three infantry divisions contained 28 Battalions.[6] These 28 Battalions consisted of both Line and Light Infantry Regiments. Belonging to the above three Infantry Divisions were the following Line Infantry Regiments: 18th (3 Battalions),[7] 32nd (2 Battalions),[7] 36th (2 Battalions),[7] 39th (2 Battalions),[7] 40th (2 Battalions),[7] 57th (3 Battalions),[7] 58th (2 Battalions),[7] 101st (2 Battalions),[8] 103rd (2 Battalions) [8] and the 104th (2 Battalions).[8] The 7th Light Infantry Regiment (3 Battalions) [8] and the 10th Light Infantry Regiment (3 Battalions) [8] also belonged to Rapp's Infantry Divisions.

- 7th Cavalry Division (Commanded by General Merlin) [5]

- National Guard Brigade (Commanded by General Berckheim) [11]

- The 3rd, 4th, and 5th Battalions of the National Guard of the Bas-Rhin [8] and the 6th, 7th and 8th Battalions of the National Guard of the Haut-Rhin.[8] Two National Guard Lancer Cavalry Regiments also appear to have been attached to Berckheims command – a Haut-Rhin National Guard Lancer Regiment (137 men) [8] and a Bas-Rhin National Guard Lancer Regiment (405 men) [8]

- Artillery: 46 guns[6]

- Total 20,000–23,000 men.[12]

VII Corps[13] – Armée des Alpes (Suchet).[14] Based at Lyons, this army was charged with the defence of Lyons and to observe the Austro-Sardinian army of Frimont. Its composition in June was:

- 22nd Infantry Division (Commanded by General Pacthod) [15]

- 23rd Infantry Division (Commanded by General Dessaix) [15]

- 15th Cavalry Division (Commanded by General Quesnel) [15]

- 6th National Guard Infantry Division [15]

- 7th National Guard Infantry Division [15]

- 8th National Guard Infantry Division [15]

- 42–46 guns[16]

- Total 13,000–23,500 men[17]

I Corps of Observation – Armée du Jura[14] Based at Belfort and commanded by General Claude Lecourbe, this army was to observe any Austrian movement through Switzerland and also observe the Swiss army of General Bachmann. Its composition in June was:

- 18th Infantry Division (Commanded by General Abbé) [18][19]

- 8th Cavalry Division (Commanded by General Castex) [18][19]

- 3rd National Guard Infantry Division[20]

- 4th National Guard Infantry Division [21]

- Artillery: Three foot artillery batteries – two of which replaced a horse artillery battery which was sent back to Rapp's V Corps (24 guns) [19][22]

- Total 5,392–8,400 men[23]

II Corps of Observation[13] – Armée du Var.[24] Based at Toulon and commanded by Marshal Guillaume Marie Anne Brune,[25] this army was charged with the suppression of any potential royalist uprisings and to observe General Bianchi's Army of Naples. Its composition in June was:

- 24th Infantry Division;[26]

- 25th Infantry Division;[26]

- Belonging to the above two infantry divisions were the following Line Infantry Regiments: 9th (3 Battalions),[7] 13th (2 Battalions),[7] 16th (2 Battalions),[7] 35th (2 Battalions)[7] and 106th (2 or 3 Battalions).[8] The 14th Light Infantry Regiment (2 Battalions) also belonged to one of these divisions.[8] Attached to Brune's army were two battalions of the 6th Light Infantry Regiment detached from Marshal Suchet's VII Corps.[8]

- Cavalry: 14th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment;[27][28]

- Artillery: 22 guns [13]

- Total 5,500–6,116 men.[29]

III Corps of Observation[13] – Army of the Pyrenees orientales.[24] Based at Toulouse and commanded by General Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen, this army observed the eastern Spanish frontier. Its composition in June was:

- 26th Infantry Division (Commanded by General Harispe) ;[27][30]

- Cavalry: 5th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment (Commanded by General Cavrois) ;[27][30][28]

- Artillery: Three foot artillery batteries (24 guns);[30][13]

- Total 3,516–7,600 men.[31]

IV Corps of Observation[13] – Army of the Pyrenees occidentales.[24] Based at Bordeaux and commanded by General Bertrand Clauzel, this army observed the western Spanish frontier. Its composition in June was:[27]

- 27th Infantry Division (Commanded by General Fressinet)[27][5]

- Cavalry: 15th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment (Commanded by General Guyon)[27][5][28]

- Artillery: Three foot artillery batteries (24 guns)[5][13]

- Total 3,516–6,800 men[32]

Army of the West [13] – Armée de l'Ouest [24] (also known as the Army of the Vendée). Commanded by General Jean Maximilien Lamarque, the army was formed to suppress the Royalist insurrection in the Vendée region of France, which remained loyal to King Louis XVIII during the Hundred Days. The army contained line units as well as gendarmes and volunteers. Its composition in June was:

- One Un-numbered Infantry Division (Commanded by General Brayer);[33]

- One Un-numbered Infantry Division (Commanded by General Travot);[33]

- Cavalry: The 4th Squadrons of the 2nd Hussar Regiment, 13th Chassuers à Cheval Regiment, 4th, 5th, 12th, 14th, 16th and 17th Dragoon Regiments [28]

- Artillery: Three foot artillery batteries (24 guns);[13]

Total 10,000–27,000 men.[34]

Seventh Coalition

The Seventh Coalition armies formed to invade France were:

Overview

The forces at the disposal of the Seventh Coalition for an invasion of France amounted to the better part of a million men. According to the returns laid out in secret sittings at the Congress of Vienna the military resources of the European states that joined the coalition, the number of troops which they could field for active operations—without unduly diminishing the garrison and other services in their respective interiors—amounted to 986,000 men. The size of the principal invasion armies (those designated to proceed to Paris) was as follows:[35]

| I | Army of Upper Rhine—(Schwartzenberg) consisting of : | |||

| Austrians | 150,000 | |||

| Bavarians | 65,000 | |||

| Württemberg | 25,000 | |||

| Baden | 16,000 | |||

| Hessians, etc., | 8,000 | |||

| I | Army of Upper Rhine—(Schwartzenberg), Total | 264,000 | ||

| II | Army of Lower Rhine—(Blücher) Prussians, Saxons, etc. | 155,000 | ||

| III | Army of Flanders—(Wellington) British, Dutch, Hanoverians, Brunswickers | 155,000 | ||

| IV | First Russian Army—(Barclay de Tolly) | 168,000 | ||

| Total | 742,000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Waterloo Campaign

Wellington's Allied Army (Army of Flanders)

Cantoned in the southern part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in what is now Belgium, Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington commanded a coalition army,[36] made up of troops from the duchies of Brunswick, and Nassau and the kingdoms of Hanover, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

In June 1815 Wellington's army of 93,000 with headquarters at Brussels was cantoned:[37]

- I Corps (Prince of Orange), 30,200, headquarters Braine-le-Comte, disposed in the area Enghien–Genappe–Mons.

- II Corps (Lord Hill), 27,300, headquarters Ath, distributed in the area Ath-Oudenarde–Ghent.

- Reserve (under Wellington himself) 25,500, lay around Brussels.

- Reserve Cavalry (Lord Uxbridge) 9,900, in the valley of the Dendre river, between Geraardsbergen and Ninove.

- Dutch light cavalry observed the frontier into the west of Leuze and Binche

The Netherlands Corps, commanded by Prince Frederick of the Netherlands did not take part in early actions of the Waterloo Campaign (it was posted to a fall back position near Braine), but did besiege some of the frontier fortresses in the rear of Wellington's advancing army.[38][39]

A Danish contingent known as the Royal Danish Auxiliary Corps commanded by General Prince Frederick of Hessen-Kassel and a Hanseatic contingent (from the free cities of Bremen, Lübeck and Hamburg) later commanded by the British Colonel Sir Neil Campbell, were also on their way to join this army,[40] both however, joined the army in July having missed the conflict.[41][42]

Wellington had very much hoped to obtain a Portuguese contingent of between 12,000 and 14,000 men that might be boarded on ships and sent to this army.[43][44] However, this contingent never materialised, as the Portuguese government were extremely uncooperative. They explained that they did not have the authority to send the Prince Regent of Portugal's forces to war without his consent (he was still in Brazil where he had been in exile during the Peninsular War and had yet to return to Portugal). They explained this even though they themselves had signed the Treaty of 15 March without his consent.[45] Besides this, the state of the Portuguese army in 1815 left much to be desired and were a shadow of their former self with much of it being disbanded.[46]

The Tsar of Russia offered Wellington his II Army Corps under general Wurttemberg,[47] but Wellington was far from keen on accepting this contingent.

Prussian Army (Army of the Lower Rhine)

This army was composed entirely of Prussians from the provinces of the Kingdom of Prussia, old and recently acquired alike. Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher commanded this army with General August Neidhardt von Gneisenau as his chief of staff and second in command.[48]

Blücher's Prussian army of 116,000 men, with headquarters at Namur, was distributed as follows:

- I Corps (von Zieten), 30,800, cantoned along the Sambre, headquarters Charleroi, and covering the area Fontaine-l'Évêque–Fleurus–Moustier.

- II Corps (Pirch I),[lower-alpha 1] 31,000, headquarters at Namur, lay in the area Namur-Hannut–Huy.

- III Corps (Thielemann), 23,900, in the bend of the river Meuse, headquarters Ciney, and disposed in the area Dinant–Huy–Ciney.

- IV Corps (Bülow), 30,300, with headquarters at Liège and cantoned around it.

German Corps (North German Federal Army)

This army was part of the Prussian Army above, but was to act independently much further south. It was composed of contingents from the following nations of the German Confederation: Electorate of Hessen, Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Grand Duchy of Oldenburg, Duchy of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Duchy of Anhalt-Bernburg, Duchy of Anhalt-Dessau, Duchy of Anhalt-Kothen, Principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, Principality of Waldeck and Pyrmont, Principality of Lippe and the Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe.[49]

Fearing that Napoleon was going to strike him first, Blücher ordered this army to march north to join the rest of his own army.[50] The Prussian General Friedrich Graf Kleist von Nollendorf initially commanded this army before he fell ill on 18 June and was replaced temperately by the Hessen-Kassel General von Engelhardt (who was in command of the Hessen division) and then by Lieutenant General Karl Georg Albrecht Ernst von Hake.[51][52] Its composition in June was:[53][54][lower-alpha 2]

- Hessen-Kassel Division (Three Hessian Brigades)- General Engelhardt

- Hessian 1st Brigade (5 battalions) – Major General Prince of Solms-Braunfels

- Hessian 2nd Brigade (7 battalions) – Major General von Muller

- Hessian Cavalry Brigade (2 regiments) – Major General von Warburg (Prussian)

- Hessian Artillery (2 six-pounder batteries) – Najor von Bardeleben (Prussian)

- Thuringian Brigade – Major General Egloffstein (Weimar)

- 1st Provisional Infantry Regiment (4 battalions):

- 2nd Provisional Infantry Regiment (3 battalions)

- 3rd Provisional Infantry Regiment (5 battalions including the Oldenbug Line Infantry Regiment (2 battalions))

Total 25,000[24]

Russian Army (I Army)

Field Marshal Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly commanded the First Russian Army. In June it consisted of the following:[55]

- III Army Corps – General Dokhturov

- IV Army Corps – General Raevsky

- V Army Corps – General Sacken

- VI Army Corps – General Langeron

- VII Army Corps – General Sabaneev[56]

- Reserve Grenadier Corps – General Yermolov

- II Reserve Cavalry Corps – General Winzingerode

- Artillery Reserve – Colonel Bogoslavsky

Total 200,000[24]

Austro-German Army (Army of the Upper Rhine)

The Austrian military contingent was divided into three armies. This was the largest of these armies, commanded by Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg. Its target was Paris. This Austrian contingent was joined by those of the following nations of the German Confederation: Kingdom of Bavaria, Kingdom of Württemberg, Grand Duchy of Baden, Grand Duchy of Hesse (Hessen-Darmstadt), Free City of Frankfurt, Principality of Reuss Elder Line and the Principality of Reuss Junior Line. Besides these there were contingents of Fulda and Isenburg. These were recruited by the Austrians from German territories that were in the process of losing their independence by being annexed to other countries at the Congress of Vienna. Finally, these were joined by the contingents of the Kingdom of Saxony, Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Duchy of Saxe-Meiningen and the Duchy of Saxe-Hildburghausen. Its composition in June was:[57]

| Corps | Commander | Men | Battalions | Squadrons | Batteries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Corps | Master General of the Ordnance, Count Colloredo | 24,400 | 86 | 16 | 8 |

| II Corps | General Prince Hohenzollern-Hechingen | 34,360 | 36 | 86 | 11 |

| III Corps | Field Marshal the Crown Prince of Württemberg | 43,814 | 44 | 32 | 9 |

| IV Corps (Bavarian Army) | Field Marshal Prince Wrede | 67,040 | 46 | 66 | 16 |

| Austrian Reserve Corps | Lieutenant Field Marshal Stutterheim | 44,800 | 38 | 86 | 10 |

| Blockade Corps | 33,314 | 38 | 8 | 6 | |

| Saxon Corps | 16,774 | 18 | 10 | 6 | |

| Totals | 264,492[lower-alpha 3] | 246 | 844 | 66 |

Swiss Army

This army was composed entirely of Swiss. The Swiss General Niklaus Franz von Bachmann commanded this army. This force was to observe any French forces that operated near its borders. Its composition in July was:[58]

- I Division – Colonel von Gady

- II Division – Colonel Fuessly

- III Division – Colonel d'Affry

- Reserve Division – Colonel-Quartermaster Finsler

Total 37,000[24]

Austro-Sardinian Army (Army of Upper Italy)

This was the second largest of Austria's contingents. Its target was Lyons. General Johann Maria Philipp Frimont commanded this army. Its composition in June was:[59]

- I Corps – Major-General(Feldmarschalleutnant) Paul von Radivojevich

- II Corps – Major-General (Feldmarschalleutnant) Ferdinand, Graf Bubna von Littitz

- Reserve Corps – Major-General (Feldmarschalleutnant) Franz Mauroy de Merville

- Sardinian Corps – Lieutenant-General Count Latour

Total 50,000[24]

Austrian Army (Army of Naples)

This was the smallest of Austria's military contingents. Its targets were Marseilles and Toulon. General Frederick Bianchi commanded this army.[lower-alpha 4] This was the Austrian army that defeated Murat's army in the Neapolitan War. It was not composed of Neapolitans as the army's name may suggest and as one author supposed.[60] There was however a Sardinian force in this area forming the garrison of Nice under Giovanni Pietro Luigi Cacherano d'Osasco[61] which may have been where the other part of this misunderstanding had arisen. Its composition in June was:[62]

- I Corps – General Adam Albert von Neipperg

- II Corps – General Johann Friedrich von Mohr

- Reserve Corps – General Laval Nugent von Westmeath

Total 23,000[24]

British Mediterranean contingent

This was Great Britain's smaller military expedition. It was composed of British troops from the garrison of Genoa under General Sir Hudson Lowe transported and supported by the Mediterranean Fleet of Lord Exmouth to Marseilles to aid a French Royalist uprising. The British landed about 4,000 men in Marseilles, made up of soldiers, marines and sailors.[63]

Spanish armies

It was planned that a Spanish army was to invade France via Perpignan and Toulouse. General Francisco Javier Castanos, 1st Duke of Bailen commanded this army.[64]

It was planned that a second Spanish army was to invade France over the river Bidassoa and into France via Bayonne and Bordeaux. General Henry Joseph O'Donnell, Count of La Bisbal commanded this army.[64]

Both Wellington's Despatches and his Supplementary Despatches show that neither of the Spanish armies contained any Portuguese contingents nor were they likely too, (See the section Portuguese contingent below), however both Chandler and Barbero state that the Portuguese did send a contingent.[24][65]

Netherlands reserve army

In order to support the Netherlands field army, plans had been made on 24 May to raise a reserve army. It wasn’t until 19 July until the organisation of the army was laid out: it was to consist of 30 infantry battalions, 18 cavalry squadrons, and four artillery batteries. The infantry was organised from the newly acquired Swiss regiments and newly raised Belgian Militia battalions; the cavalry from the reserves of all nine cavalry regiments, including the colonial hussars and Belgian Militia Carabiniers. By then, the Coalition armies had already set up camp around Paris. The army, existing largely only on paper, was disbanded after three months.[66] Only the 43rd National Militia Infantry Battalion, part of the 4th Infantry Brigade (2nd Infantry Division), was deployed in the observation of Bouillon.[67][68]

Commander: Lieutenant-General baron Tindal, Quartermaster / Adjudant-general: Major General D.L. Vermaesen:[66]

- 1st Infantry Division, Lieutenant-general baron Tindal

- 2nd Infantry Division, Lieutenant general Cort Heyligers

- Cavalry Division, Lieutenant general baron Evers (formed partially)

Prussian Reserve Army

Besides the four Army Corps that fought in the Waterloo Campaign listed above that Blücher took with him into the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Prussia also had a reserve army stationed at home in order to defend its borders.

This consisted of:[69]

- V Army Corps – Commanded by General Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg

- VI Army Corps – Commanded by General Bogislav Friedrich Emanuel von Tauentzien

- Royal Guard (VIII Corps) – Commanded by General Charles II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Royal Danish Auxiliary Corps and Hanseatic Contingent

A Danish contingent known as the Royal Danish Auxiliary Corps commanded by General Prince Frederick of Hessen-Kassel and a Hanseatic contingent (from the free cities of Bremen, Lübeck and Hamburg) commanded by the British Colonel Sir Neil Campbell, were also on their way to join Wellington's army,[40] both however, joined the army in July having missed the conflict.[50][42]

Portuguese contingent

Wellington had very much hoped to obtain a Portuguese contingent of 12–14,000 men that might be boarded on ships and sent to this army.[43][44] However, this contingent never materialised, as the Portuguese government were extremely uncooperative. They explained that they did not have the authority to send the Prince Regent of Portugal's forces to war without his consent (he was still in Brazil where he had been in exile during the Peninsular War and had yet to return to Portugal). They explained this even though they themselves had signed the Treaty of 15 March without his consent.[45] Besides this, the state of the Portuguese army in 1815 left much to be desired and it was a shadow of its former self with much of it being disbanded.[46]

Russian 2nd (Reserve) Army

The Second Russian Army was behind the First Russian Army to support it if required.

- Imperial Guard Corps

- I Army Corps

- II Army Corps, commanded by General Wurttemberg

- I Grenadier Division

- I Reserve Cavalry Corps

Russian support for Wellington

The Tsar of Russia offered Wellington the II Army Corps under General Wurttemberg from his Reserve Army,[47] but Wellington was far from keen on accepting this contingent.

Notes

- General Georg von Pirch is known as "Pirch I", because the Prussian army used Roman numerals to distinguish officers of the same name, in this case from his brother, seven years his junior, Otto Karl Lorenz Pirch II (Thiers 1865, p. 573 (footnote)).

- A third brigade, the Mecklenburg Brigade commanded by General Prince of Mecklenburg-Schwerin is included in Plotho, but not by Hofschröer & Embleton (Plotho 1818, p. 56; Hofschröer & Embleton 2014, p. 42).

- Although Siborne estimated the number at 264,492, David Chandler estimated the number 232,000 (Chandler 1981, p. 27)

- Chandler places the army under the command of General Onasco,(Chandler 1981, p. 30) but Plotho and Vaudoncourt name the commander as General Bianchi (Vaudoncourt 1826, Book I, Chapter I, p. 94.; Plotho 1818, Appendix pp. 76–77).

- Chesney 1869, p. 34.

- Chesney 1869, p. 35.

- Beck 1911, p. 371.

- Chandler 1981, p. 180.

- Couderc de Saint-Chamant 1902, p. 322.

- Charras 1857, p. 40.

- Regnault 1935, p. 312.

- Regnault 1935, p. 313.

- Gay de Vernon 1865, p. 130.

- Regnault 1935, p. 308.

- Regnault 1935, p. 157.

- Armée du Rhin men

- 20,000 (Beck 1911, p. 371)

- 20,4056. (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- 23,000. (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- Chalfont 1979, p. 205.

- Chandler 1981, p. 181.

- Zins 2003, pp. 380–384.

- Armée des Alpes guns

- 42 guns. (Zins 2003, pp. 380–384)

- 46 guns. (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- Armée des Alpes. Men

- 13,000–20,000 (Siborne 1895, p. 775)

- 23,500 (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- 15,767 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- Smith 1998, p. 551.

- Blaison 1911, p. 26.

- Blaison 1911, p. 27.

- Blaison 1911, p. 29.

- Blaison 1911, p. 40–41.

- Armée du Jura: men

- 5,392 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- 8,400 (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- Chandler 1981, p. 30.

- Siborne 1895, p. 775,779.

- Vaudoncourt 1826, Book I, Chapter I, p. 110.

- Houssaye 2005, p.

- Regnault 1935, p. 309.

- Armée du Var: men

- 5,500 (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- 6,116 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- Couderc de Saint-Chamant 1902, p. 323.

- III Corps of Observation, Men:

- 3,516 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- 7,600 (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- IV Corps of Observation

- 3,516 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- 6,800. (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- Lasserre 1906, p. 114.

- Army of the West, men:

- 10,000. (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- Upwards of 20,000 men.(Schom 1992, p. 152)

- 27,000 men.(Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- Alison 1843, p. 520 cites: Plotho iv., Appendix, p. 62; and Capefigue, i., 330, 331.

- Bowden 1983, Chapter 3.

- Beck 1911, p. 372,373.

- Siborne 1895, pp. 765, 766.

- McGuigan 2009, § Siege Train.

- Plotho 1818, Appendix pp. 34,35.

- Hofschröer 2006, pp. 82, 83.

- Sørensen 1871, pp. 360–367.

- Glover 1973, p. 181.

- Gurwood 1838, p. 281.

- Wellesley 1862, pp. 573, 574.

- Wellesley 1862, p. 268.

- Wellesley 1862, p. 499.

- Bowden 1983, Chapter 2.

- Plotho 1818, p. 54.

- Hofschröer 1999, p. 182.

- Hofschröer 1999, pp. 179, 182.

- Pierer 1857, p. 605, 2nd column.

- Plotho 1818, Appendix (Chapter XII) p. 56.

- Hofschröer & Embleton 2014, p. 42.

- Plotho 1818, Appendix (Chapter XII) pp. 56–62.

- Mikaberidze 2002.

- Siborne 1895, p. 767.

- Chapuisat 1921, table 2.

- Plotho 1818, Appendix pp. 74–76.

- Chandler 1981, p. 27.

- Schom 1992, p. 19.

- Plotho 1818, Appendix pp. 76,77.

- Parkinson 1934, pp. 416–418.

- Peltier 1815, p. 743.

- Barbero 2006, Map of Allied Advances in June/July 1815

- Raa 1980, p. .

- Service records of the officers of the 43rd National Militia Battalion, National Archives, the Hague

- Anonymous 1838, p. .

- Plotho 1818, pp. 36–55.

References

- Alison, Archibald (1843). History of Europe from the commencement of the French Revolution in 1789, to the restoration of the Bourbons in 1815. Vol. 4. Harper & Brothers.

- Anonymous (1838). Geschichte des Feldzugs von 1815 in den Niederlanden und Frankreich als Beitrag zur Kriegsgeschichte der neuern Kriege. […] Part II (in German). Berlin, Posen and Bromberg: Ernst Siegfried Mittler.

- Beck, Archibald Frank (1911). "Waterloo Campaign, 1815". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 371–381.

- Barbero, Alessandro (2006). The Battle: a new history of Waterloo. Walker & Company. ISBN 0-8027-1453-6.

- Blaison, Capitaine (1911). La Couverture d'une Place Forte en 1815: Belfort et Le Corps de Jura. Paris: Henri Charles Lavauzelle.

- Bowden, Scott (1983). Armies at Waterloo: a detailed analysis of the armies that fought history's greatest Battle. Empire Games Press. ISBN 0-913037-02-8.

- Chalfont, Lord; et al. (1979). Waterloo: Battle of Three Armies. Sidgwick and Jackson.

- Chandler, David (1981) [1980]. Waterloo: The Hundred Days. Osprey Publishing.

- Chapuisat, Édouard (1921). Der Weg zur Neutralität und Unabhängigkeit 1814 und 1815. Bern: Oberkriegskommissariat. (also published as: Vers la neutralité et l'indépendance. La Suisse en 1814 et 1815, Berne: Commissariat central des guerres)

- Charras, Lt. Colonel (1857). Histoire de la Campagne de 1815: Waterloo. Brussels: Meline Cans et Comp – J. Hetzel et Comp. p. 40.

- Chesney, Charles Cornwallis (1869). Waterloo Lectures. London: Longmans Green and Co. (In print edition published by Kessinger Publishing, LLC (25 July 2006) ISBN 1-4286-4988-3)

- Couderc de Saint-Chamant, Henri (1902). Napoleon: Ses Dernieres Armees. Paris: Ernest Flammarion, Editeur.

- Gay de Vernon, Le Baron (1865). Historique du 2e Regiment de Chasseurs a Cheval depuis sa Creation Jusqu'en 1864. Paris: Libraire Militaire.

- Glover, Michael (1973). Wellington as Military Commander. London: Sphere Books.

- Gurwood, Lt. Colonel (1838). The Dispatches of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington. Vol. 12. [publisher needed].

- Hofschröer, Peter (2006). 1815 The Waterloo Campaign: Wellington, his German allies and the Battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras. Vol. 1. Greenhill Books.

- Hofschröer, Peter (1999). 1815; The Waterloo Campaign: The German victory, from Waterloo to the fall of Napoleon. Vol. 2. Greenhill Books. pp. 179. ISBN 1-85367-368-4.

- Hofschröer, Peter; Embleton, Gerry (2014). The Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine 1815. Osprey Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-78200-619-0.

- Houssaye, Henri (2005). Napoleon and the Campaign of 1815: Waterloo. Naval & Military Press Ltd.

- Lasserre, Bertrand (1906). Les Cent Jours en Vendée: le Général Lamarque et l'Insurrection Royaliste. Paris: Plon-Nourrit.

- McGuigan, Ron (2009) [2001]. "Anglo-Allied Army in Flanders and France – 1815: Subsequent Changes in Command and Organization". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2002). "Russian Generals of the Napoleonic Wars: General Ivan Vasilievich Sabaneev". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Parkinson, C. (1934). "CHAPTER XII - Algiers". Edward Pellew. London: Northcote. pp. 416–418.

- Peltier, Jean-Gabriel (1815). L'Ambigu. Vol. I. p. 743.

- Pierer, H.A. (1857). "Russisch-Deutscher Krieg gegen Frankreich 1812-1815". Pierer's Universal-Lexikon (in German). Vol. 14. p. 605, 2nd column.

- Plotho, Carl von (1818). Der Krieg des verbündeten Europa gegen Frankreich im Jahre 1815. Berlin: Karl Friedrich Umelang.

- Raa, F.J.G. ten (1980) [1900]. De uniformen van de Nederlandsche zee—en landmacht hier te lande en in de kolonien... (in Dutch). Historical Section of the Royal Netherlands Army. OCLC 768909746. OL 3849493M.

- Regnault, Jean (1935). La Campagne de 1815: Mobilisation et Concentration. Paris: Libraire Militaire L. Fournier.

- Schom, Alan (1992). One Hundred Days: Napoleon's road to Waterloo. New York: Atheneum. pp. 19, 152.

- Siborne, William (1895). "Supplement section". The Waterloo Campaign 1815 (4th ed.). Birmingham, 34 Wheeleys Road. pp. 767–780.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill Books.

- Sørensen, Carl (1871). Kampen om Norge i Aarene 1813 og 1814. Vol. 2. Kjøbenhavn.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thiers, Adolphe (1865). History of the Consulate and the Empire of France Under Napoleon. Lippincott. p. 573.

- Vaudoncourt, Guillaume de (1826). Histoire des Campagnes de 1814 et 1815 en France. Vol. Tome II. Paris: A. de Gastel.

- Wellesley, Arthur (1862). Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington. Vol. 10. London: United Services, John Murray.

- Zins, Ronald (2003). 1815 L'armée des Alpes et Les Cent-Jours à Lyon. Reyrieux: H. Cardon.