Bosavi languages

The Bosavi or Papuan Plateau languages belong to the Trans-New Guinea language family according to the classifications made by Malcolm Ross and Timothy Usher. This language family derives its name from Mount Bosavi and the Papuan Plateau.

| Bosavi | |

|---|---|

| Papuan Plateau | |

| Geographic distribution | Papuan Plateau, Papua New Guinea |

| Linguistic classification | Trans–New Guinea

|

| Glottolog | bosa1245 |

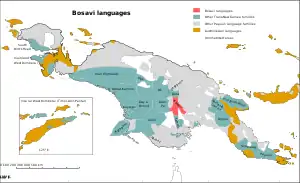

Map: The Bosavi languages of New Guinea

The Bosavi languages

Other Trans–New Guinea languages

Other Papuan languages

Austronesian languages

Uninhabited | |

Geographically, the Bosavi languages are situated to the east and south of the East Strickland group. They can be found around Mount Bosavi, located east of the Strickland River and southwest of the western edge of the central highlands of Papua New Guinea. Although no extensive subgrouping analysis has been conducted, Shaw's lexicostatistical study in 1986 provides some insights.

Based on this study, it is indicated that Kaluli and Sonia exhibit a significant lexical similarity of 70%, which is higher than any other languages compared. Therefore, it is likely that these two languages form a subgroup. Similarly, Etoro and Bedamini share a subgroup with a lexical similarity of 67%. The languages Aimele, Kasua, Onobasulu, and Kaluli-Sunia exhibit more shared isoglosses among themselves than with the Etoro-Bedamini group. Some of these shared isoglosses are likely to be innovations.[1]

Languages

The languages, which are closely related are:[1]

- Mount Bosavi: Kaluli–Sonia, Aimele (Kware), Kasua

- Onobasulu

- Mount Sisa: Edolo–Beami

- Dibiyaso (Bainapi)

Its worth noting these languages share at best 70% lexical (vocabulary) similarity, as in the case of Kaluli-Sonia, and Edolo-Beami.[1] The rest of related languages likely shares around 10-15% lexical similarities.

The unity of the Bosavi languages was quantitatively demonstrated by Evans and Greenhill (2017).[2]

Palmer et al. (2018) consider Dibiyaso to be a language isolate.[3]

Pronouns

Pronouns are:

sg pl 1 *na *ni- 2 *ga *gi- 3 *ya *yi-

Vocabulary comparison

The following basic vocabulary words are from the Trans-New Guinea database:[4]

| gloss | Aimele | Beami | Biami | Edolo | Kaluli | Kaluli (Bosavi dialect) | Kasua | Onabasulu | Sonia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | mufa | tialuna; tiaruma | taluba | b~pusʌ | mise; misẽ | pesʌi | bizei; pesai | kuni | eneipi |

| hair | mufa fɔnɔ | hinabu; osa | hinabo | b~pusʌ heni | misẽ fɔ̃; mise foon | medafɔn | bizei fʌnu; pesaifano | alu; kuni alu | eneipi fɔn |

| ear | keleni | kẽ | kȩ | kɛhe | kenẽ; malo | kælæn | kenane; kinɛli | kɔheni; koneni | ekadem |

| eye | si | si | sii | si | si | si | si | si | |

| nose | migi | mi | mi | migʌni | migi | mi; mĩ | mi; mĩ | miki | |

| tooth | bisi | pese; pẽsẽ | pese | p~bese | beso; bis | pes | apa | pese | ʌnenʌ |

| tongue | dabisẽ | eri; kɔnɛ̃su | kona̧su | eli | eʌn; sano | inem | tepe; tepɛ | eane; ɛane | tʌbise |

| leg | inebi | emo | emo | emɔ | gidaafoo; gip | onatu; unɛtu | emo; emɔ | eisep | |

| louse | tede | imu | imu | imũ | fe; fẽ | tekeape | arupai; pfɛi | (fe); fẽ | fi |

| dog | ãgi | wæːme; weːme | wæmi | ɔgɔnɔ | gasa; kasʌ | kasa | kasoro; kʌsoro | gesu; kesɔ | wɛi |

| pig | kẽ | gebɔ | suguʌ | kabɔ | kɔpɔľɔ | tɔfene | kɛ | ||

| bird | abɔ | mæni | hega; mæni | hayʌ | ɔ̃bẽ; oloone; oobaa | anemae; ɛnim | haga; haka | ʌbɔ | |

| egg | abɔ us̪u | ɔsɔ | oso | isɔ | ɔ̃bẽ uš; us | natape; ufu | hokaisu; sɔ | ʌtʌm | |

| blood | omani | hæːľe | heale | hiʌle | hɔbɔ; hooboo | bebetʌ; pepeta | ibi | hʌbʌ | |

| bone | ki | kasa; koso | kasa | kiwiː | ki | ki; kiː | kiwi | uku | |

| skin | kãfu | kadofo; kadɔfɔ | kadofo | kʌdɔfɔ | dɔgɔf; toogoof | kapo | kapo; kʌːpɔ | tomola; tɔmɔla | ʌkʌf |

| breast | buː | toto; tɔtɔ | toto | tɔtɔ | bo; bu | bo | bɔ; po | bu | bɔ |

| tree | yebe | ifa | ifa | i | i | i; tai | i | yep | |

| man | kɔlu | tunu | tunu̧ | tɔnɔ | kalu | senae; senɛ | inɔlɔ; inoro | ʌsenʌ | |

| woman | kaisale | uda | uda | udia | ga; kesali; kesari | kesare; kesʌľe | ido; idɔ | nʌisɔʌ | |

| sun | ofɔ | esɔ; eṣɔ | eso | esɔ | of; ɔf | opo | ɔbɔ; opo | haro; hɔlɔ | of |

| moon | ole | aubi | awbi | aube | ili | kunɛi; opo | aube; aubo | weľe | |

| water | hãni | hãlɔ̃; harõ | ha̧lo | ɔ̃tã | hɔ̃n; hoon | hoŋ | hano; hʌnɔ̃ | hano; hanɔ | mɔ͂ |

| fire | di | daru; nalu | dalu | nulu | de; di | de | homatos; tei | de; ti | de |

| stone | dɔa | igi | kele | igi | u | etewʌ; etoa | abane | ka | |

| road, path | nɔgo | isu | |||||||

| name | wi | diɔ; diɔ̃ | dio | ẽi | wi | unũ | wi | imi | |

| eat | mayã | na; naha | na-imo- | nahãː | maya | kinatapo; mɛnẽ | namana; namena | menʌ | |

| one | ageli | afai | afa̧i̧ | age | ãgel; angel | semeti; tekeape | agale | itidi | |

| two | ageleweli | adunã | aduna | agedu | a̧dep; ãdip | ɛľipi | aganebo; aida | ani |

Word count, and grammar sketches.

| Kaluli | Sonia | Aimele | Kasua | Onobasulu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word count | 400 | 140 | 1,000 | ||

| Grammar sketches | 2,500 | 600 |

References

- The Trans New Guinea family Andrew Pawley and Harald Hammarström

- Evans, Bethwyn; Greenhill, Simon (2017). "A combined comparative and phylogenetic analysis of the Bosavi and East Strickland languages" (PDF). 4th Workshop on the Languages of Papua. Universitas Negeri Papua, Manokwari, West Papua, Indonesia.

- Palmer, Bill (2018). "Language families of the New Guinea Area". In Palmer, Bill (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide. The World of Linguistics. Vol. 4. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-3-11-028642-7.

- Greenhill, Simon (2016). "TransNewGuinea.org - database of the languages of New Guinea". Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- Ross, Malcolm (2005). "Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages". In Andrew Pawley; Robert Attenborough; Robin Hide; Jack Golson (eds.). Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 15–66. ISBN 0858835622. OCLC 67292782.

- Shaw, R.D. "The Bosavi language family". In Laycock, D., Seiler, W., Bruce, L., Chlenov, M., Shaw, R.D., Holzknecht, S., Scott, G., Nekitel, O., Wurm, S.A., Goldman, L. and Fingleton, J. editors, Papers in New Guinea Linguistics No. 24. A-70:45-76. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1986. doi:10.15144/PL-A70.45

- Shaw, R.D. "A Tentative Classification of the Languages of the Mt Bosavi Region". In Franklin, K. editor, The linguistic situation in the Gulf District and adjacent areas, Papua New Guinea. C-26:187-215. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1973. doi:10.15144/PL-C26.187