Nara (city)

Nara (奈良市, Nara-shi, [naꜜɾa] ⓘ) is the capital city of Nara Prefecture, Japan. As of 2022, Nara has an estimated population of 367,353 according to World Population Review, making it the largest city in Nara Prefecture and sixth-largest in the Kansai region of Honshu. Nara is a core city located in the northern part of Nara Prefecture bordering the Kyoto Prefecture.

Nara

奈良市 | |

|---|---|

| Nara City | |

From top left: Todai-ji temple, Toshodai-ji temple, Yakushi-ji temple, the sika deer in Nara Park, the garden of the former Daijyo-in temple and Kasuga-taisha shrine | |

Flag  Seal | |

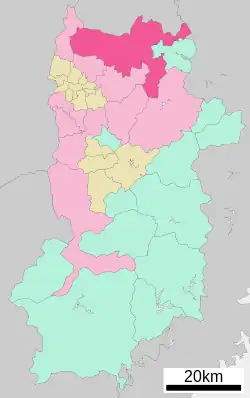

Location of Nara in Nara Prefecture | |

| |

Nara Location in Japan | |

| Coordinates: 34°41′04″N 135°48′18″E | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Kansai |

| Prefecture | Nara Prefecture |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gen Nakagawa |

| Area | |

| • Total | 276.84 km2 (106.89 sq mi) |

| Population (2022) | |

| • Total | 367,353[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+09:00 (JST) |

| City hall address | 1-1-1 Nijō-ōji, Nara-shi, Nara-ken 630-8580 |

| Website | City of Nara |

| Symbols | |

| Bird | Japanese bush warbler |

| Flower | Nara yaezakura |

| Tree | Quercus gilva |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara |

| Includes | |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii)(iii)(iv)(vi) |

| Reference | 870 |

| Inscription | 1998 (22nd Session) |

| Area | 617 ha (1,520 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 1,962.5 ha (4,849 acres) |

Nara was the capital of Japan during the Nara period from 710 to 794 as the seat of the Emperor before the capital was moved to Kyoto. Nara is home to eight temples, shrines, and ruins, specifically Tōdai-ji, Saidai-ji, Kōfuku-ji, Kasuga Shrine, Gangō-ji, Yakushi-ji, Tōshōdai-ji, and the Heijō Palace, together with Kasugayama Primeval Forest, collectively form the Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Etymology

By the Heian period, a variety of different characters had been used to represent the name Nara: 乃楽, 乃羅, 平, 平城, 名良, 奈良, 奈羅, 常, 那良, 那楽, 那羅, 楢, 諾良, 諾楽, 寧, 寧楽 and 儺羅.

A number of theories for the origin of the name "Nara" have been proposed, and some of the better-known ones are listed here. The second theory in the list, from the notable folklorist Kunio Yanagita (1875–1962), is most widely accepted at present.

- The Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan, the second oldest book of classical Japanese history) suggests that "Nara" was derived from narasu (to flatten, to level). According to this account, in September in the tenth year of Emperor Sujin, "leading selected soldiers (the rebels) went forward, climbed Nara-yama (hills lying to the north of Heijō-kyō) and put them in order. Now the imperial forces gathered and flattened trees and plants. Therefore the mountain is called Nara-yama." Though the narrative itself is regarded as a folk etymology and few researchers regard it as historical, this is the oldest surviving suggestion, and is linguistically similar to the following theory by Yanagita.

- "Flat land" theory (currently most widely accepted): In his 1936 study of placenames,[2] the author Kunio Yanagita states that "the topographical feature of an area of relatively gentle gradient on the side of a mountain, which is called taira in eastern Japan and hae in the south of Kyushu, is called naru in the Chūgoku region and Shikoku (central Japan). This word gives rise to the verb narasu, adverb narashi, and adjective narushi." This is supported by entries in a dialect dictionary[3] for nouns referring to flat areas: naru (found in Aida District, Okayama Prefecture and Ketaka District, Tottori Prefecture) and naro (found in Kōchi Prefecture); and also by an adjective narui which is not standard Japanese, but is found all across central Japan, with meanings of "gentle", "gently sloping", or "easy". Yanagita further comments that the way in which the fact that so many of these placenames are written using the character 平 ("flat"), or other characters in which it is an element, demonstrates the validity of this theory. Citing a 1795 document, Inaba-shi (因幡志) from the province of Inaba, the eastern part of modern Tottori, as indicating the reading naruji for the word 平地 (standard reading heichi, meaning "level/flat ground/land/country, a plain"), Yanagita suggests that naruji would have been used as a common noun there until the modern period. Of course, the fact that historically "Nara" was also written 平 or 平城 as above is further support for this theory.

- The idea that Nara is derived from 楢 nara (Japanese for "oak, deciduous Quercus spp.") is the next most common opinion. This idea was suggested by a linguist, Yoshida Togo.[4] This noun for the plant can be seen as early as in Man'yōshū (7–8th century) and Harima-no-kuni Fudoki (715). The latter book states the place name Narahara in Harima (around present-day Kasai) derives from this nara tree, which might support Yoshida's theory. Note that the name of the nearby city of Kashihara (literally "live oak plain") contains a semantically similar morpheme (Japanese 橿 kashi "live oak, evergreen Quercus spp.").

- Nara could be a loanword from Old Korean, related to Middle Korean narah and Modern Korean nara (나라: "country", "nation", "kingdom"). This idea was put forward by the linguist Matsuoka Shizuo.[5] American linguist Samuel E. Martin notes that the earliest attestation of this word in Korean sources—given in an eighth-century hyangga text, in the phonogramic form 國惡—should be read as NAL[A-]ak. This is similar to the form implied by the Old Japanese writings of Nara that transcribe the second syllable with 楽 (raku), and Martin notes that the city name has been "long suspected of being a borrowing from the Korean word".[6] Kusuhara et al. argues that this hypothesis cannot account for the fact there are many places named Nara, Naru and Naro besides this Nara.[7]

- There is the idea that Nara is akin to Tungusic na.[8] In some Tungusic languages such as Orok (and likely Goguryeo language), na means earth, land or the like. Some have speculated about a connection between these Tungusic words and Old Japanese nawi, an archaic and somewhat obscure word that appears in the verb phrases nawi furu and nawi yoru ('an earthquake occurs, to have an earthquake').[9]

The "flat land" theory is adopted by Nihon Kokugo Daijiten (the largest dictionary of Japanese language), various dictionaries for place names,[7][10][11] history books on Nara,[12] and the like today, and it is regarded as the most likely.

History

Pre-Nara and origins

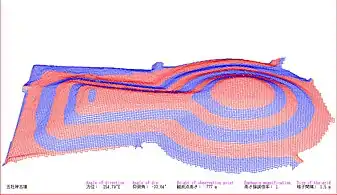

There are a number of megalithic tombs or kofun in Nara, including Gosashi Kofun, Hishiage Kofun (ヒシアゲ古墳), Horaisan Kofun (宝来山古墳), Konabe Kofun (コナベ古墳), Saki Ishizukayama Kofun (佐紀石塚山古墳), Saki Misasagiyama Kofun (佐紀陵山古墳), and Uwanabe Kofun (ウワナベ古墳).

By decree of an edict on March 11, 708 AD, Empress Genmei ordered the court to relocate to the new capital, Nara.[13] Once known as Heijō or Heijō-kyō, the city was established as Japan's first permanent capital in 710 CE; it was the seat of government until 784 CE, albeit with a five-year interruption, lasting from 741 to 745 CE.[13][14] Heijō, as the ‘penultimate court’, however, was abandoned by the order of Emperor Kammu in 784 CE in favor of the temporary site of Nagaoka, and then Heian-kyō (Kyoto) which retained the status of capital for 1,100 years, until the Meiji Emperor made the final move to Edo in 1869 CE.[15][14][16] This first relocation was due to the court's transformation from an imperial nobility to a force of metropolitan elites and new technique of dynastic shedding which had refashioned the relationship between court, nobility, and country.[15] Moreover, the ancient capital lent its name to Nara period.[14]

As a reactionary expression to the political centralization of China, the city of Nara (Heijō) was modeled after the Tang capital at Chang’an.[16] Nara was laid out on a grid—which was based upon the Handen system—whereby the city was divided by four great roads.[14] Likewise, according to Chinese cosmology, the ruler's place was fixed like the pole star. By dominating the capital, the ruler brought heaven to earth.[17] Thus, the south-facing palace centered at the north, bisected the ancient city, instituting ‘Right Capital’ and ‘Left Capital’ zones.[15][17] As Nara came to be a center of Buddhism in Japan and a prominent pilgrimage site, the city plan incorporated various pre-Heijō and Heijō period temples, of which the Yakushiji and the Todaiji still stand.[15][16]

Gosashi tomb

Gosashi tomb

Politics

A number of scholars have characterized the Nara period as a time of penal and administrative legal order.[18] The Taihō Code called for the establishment of administrative sects underneath the central government, and modeled many of the codes from the Chinese Tang dynasty.[19] The code eventually disbanded, but its contents were largely preserved in the Yōrō Code of 718.[19]

Occupants of the throne during the period gradually shifted their focus from military preparation to religious rites and institutions, in an attempt to strengthen their divine authority over the population.[18]

Religion and temples

With the establishment of the new capital, Asuka-dera, the temple of the Soga clan, was relocated within Nara.[20] The Emperor Shōmu ordered the construction of Tōdai-ji Temple (largest wooden building in the world) and the world's largest bronze Buddha statue.[16] The temples of Nara, known collectively as the Nanto Shichi Daiji, remained spiritually significant even beyond the move of the political capital to Heian-kyō in 794, thus giving Nara a synonym of Nanto (南都 "the southern capital").

On December 2, 724 AD, in order to increase the visual "magnificence" of the city, an edict was ordered by the government for the noblemen and the wealthy to renovate the roofs, pillars, and walls of their homes, although at that time this was unfeasible.[13]

Sightseeing in Nara city became popular in the Edo period, during which several visitors' maps of Nara were widely published.[21] During the Meiji Period, the Kofukuji Temple lost some land and its monks were converted into Shinto priests, due to Buddhism being associated with the old shogunate.[22]

Tōdai-ji is a Buddhist temple and the world's largest wooden building (8th century)

Tōdai-ji is a Buddhist temple and the world's largest wooden building (8th century) Yakushi-ji was completed in 680

Yakushi-ji was completed in 680 Kōfuku-ji was built in 669

Kōfuku-ji was built in 669 Houtokuji (Yagyu Clan Tomb)

Houtokuji (Yagyu Clan Tomb) Himuro Shrine, established in 710

Himuro Shrine, established in 710

Modern Nara

Although Nara was the capital of Japan from 710 to 794, it was not designated a city until 1 February 1898. Nara has since developed from a town of commerce in the Edo and Meiji periods to a modern tourist city, due to its large number of historical temples, landmarks and national monuments. Nara was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites list in December 1998.[23] The architecture of some shops, ryokans and art galleries has been adapted from traditional merchant houses.[22]

Nara holds traditional festivals every year, including the Neri-Kuyo Eshiki, a spring festival held in Todaiji temple for over 1,000 years; and the Kemari Festival, in which people wear costumes ranging across 700 years and play traditional games).[24]

In 1909, Tatsuno Kingo designed the Nara Hotel, whose architecture combined modern elements with traditional Japanese style.[22]

On 8 July 2022, former Prime Minister of Japan Shinzo Abe was shot and killed by Tetsuya Yamagami with a homemade firearm in Nara while campaigning.[25] There is currently an ongoing investigation into the assassination.[26]

Geography

The city of Nara lies in the northern end of Nara Prefecture, directly bordering Kyoto Prefecture to its north. The city is 22.22 km (13.81 mi) from North to South, from East to West. As a result of the latest merger, effective April 1, 2005, that combined the villages of Tsuge and Tsukigase with the city of Nara, the city now borders Mie Prefecture directly to its east. The total area is 276.84 km2 (106.89 sq mi).[27]

Nara city, as well as several important settlements (such as Kashihara, Yamatokōriyama, Tenri, Yamatotakada, Sakurai and Goze[28]), are located in the Nara Basin.[29] This makes it the most densely-populated region of Nara Prefecture.[29]

The downtown of Nara is on the east side of the ancient Heijō Palace site, occupying the northern part of what was called the Gekyō (外京), literally the outer capital area. Many of the public offices (e.g. the Municipal office, the Nara Prefectural government, the Nara Police headquarters, etc.) are located on Nijō-ōji (二条大路), while Nara branch offices of major nationwide banks are on Sanjō-ōji (三条大路), with both avenues running east–west.

The highest point in the city is at the peak of Kaigahira-yama at an altitude of 822.0 m (2,696.85 ft) (Tsugehayama-cho district), and the lowest is in Ikeda-cho district, with an altitude of 56.4 m (185.04 ft).[30]

Climate

The climate of Nara Prefecture is generally temperate, although there are notable differences between the north-western basin area and the rest of the prefecture which is more mountainous.

The basin area climate has an inland characteristic, as represented in the higher daily temperature variance, and the difference between summer and winter temperatures. Winter temperatures average approximately 3 to 5 °C (37 to 41 °F), and from 25 to 28 °C (77 to 82 °F) in the summer with highest readings reaching close to 35 °C (95 °F). There has not been a single year since 1990 with more than 10 days of snowfall recorded by Nara Local Meteorological Observatory.

The climate in the rest of the prefecture is that of higher elevations especially in the south, with −5 °C (23 °F) being the extreme minimum in winter. Heavy rainfall is often observed in summer. The annual accumulated rainfall totals as much as 3,000 to 5,000 mm (118.11 to 196.85 in), which is among the heaviest in Japan and indeed in the world outside the equatorial zone.

Spring and fall temperatures are temperate and comfortable. The mountainous region of Yoshino has been long popular for viewing cherry blossoms in the spring. In autumn, the southern mountains are also a popular destination for viewing fall foliage.

| Climate data for Nara (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1953–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

36.5 (97.7) |

38.1 (100.6) |

39.3 (102.7) |

36.9 (98.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.9 (76.8) |

39.3 (102.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

27.4 (81.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

28.5 (83.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

2.2 (36.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

1.4 (34.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 52.4 (2.06) |

63.1 (2.48) |

105.1 (4.14) |

98.9 (3.89) |

138.5 (5.45) |

184.1 (7.25) |

173.5 (6.83) |

127.9 (5.04) |

159.0 (6.26) |

134.7 (5.30) |

71.2 (2.80) |

56.8 (2.24) |

1,365.1 (53.74) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 1 (0.4) |

3 (1.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

5 (2.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.5 mm) | 7.6 | 8.2 | 11.2 | 10.6 | 10.8 | 13.0 | 12.2 | 9.0 | 11.4 | 10.1 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 120.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70 | 69 | 67 | 65 | 68 | 75 | 76 | 73 | 76 | 77 | 76 | 73 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 115.2 | 116.8 | 156.4 | 179.0 | 189.5 | 136.6 | 158.8 | 204.4 | 152.8 | 152.1 | 135.1 | 124.4 | 1,821.1 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[31] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Demographics

As of April 1, 2017, the city has an estimated population of 359,666 and a population density of 1,300 persons per km2. There were 160,242 households residing in Nara.[32] The highest concentration of both households and population, respectively about 46,000 and 125,000, is found along the newer bedtown districts, along the Kintetsu line connecting to Osaka.

There were about 3,000 registered foreigners in the city, of which Koreans and Chinese are the two largest groups with about 1,200 and 800 people respectively.

Landmarks and culture

Buddhist temples

Former imperial palace

Museums

Gardens

- Former Daijō-in Gardens (旧大乗院庭園)

- Isuien Garden

- Kyūseki Teien

- Manyo Botanical Garden, Nara

- Yoshiki-en

- Yagyū Iris Garden, Nara (柳生花しょうぶ園)

Other

- Naramachi

- Nara Park

- Nara Hotel

- Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties

- Yagyū

- Zutō (頭塔)

Music

- Tipsy night, a rock band from Nara, contributed the theme song for the Naruto: Gekitō Ninja Taisen! 4 (僕の愛してるだれもいない) games

Events

- Gallery

Tōdai-ji Temple Daibutsuden Hall, the world's largest wooden building

Tōdai-ji Temple Daibutsuden Hall, the world's largest wooden building Kōfuku-ji in the center of Nara

Kōfuku-ji in the center of Nara

Deer in Nara

According to the legendary history of Kasuga Shrine, the god Takemikazuchi arrived in Nara on a white deer to guard the newly built capital of Heijō-kyō.[33] Since then, the deer have been regarded as heavenly animals, protecting the city and the country.[33]

Tame sika deer (also known as spotted deer or Japanese deer) roam through the town, especially in Nara Park.[27][30][34][35][36] In 2015, there were more than 1,200 sika deer in Nara.[34][35][36] Snack vendors sell sika senbei (deer crackers) to visitors so they can feed the deer.[34][35][36] Some deer have learned to bow in order to receive senbei from people.[34][35][36]

A 2009 study by Harumi Torii (who is the assistant professor of wildlife management at Nara University of Education,) in which necropsies of deceased shika deer in Nara park were conducted, found that the deer in Nara park were malnourished from not having enough grass to eat, and eating too many rice crackers and other human food. The rice crackers commonly fed to the deer lack fiber and other nutrients deer require, so when the deer eat too many rice crackers it causes the gut microbiome in the deer to become unbalanced, among other problems. 7 out of 8 deer dissected had a “kidney fat index” (which measures how much fat has attached to the kidneys) below 40%, which indicates malnutrition in the deer. And of those 7, some had kidney fat below 10%, which indicates starvation. Compared to male shika deer outside of Nara park, which weigh about 50 kilograms on average, the male shika deer in Nara park only weigh 30 kilograms on average. The color of the femoral marrow in Nara park’s deer was also abnormal, indicating malnourishment. When living deer in Nara park were observed during the study, it was discovered that rice crackers made up about one third of the average deer’s diet in Nara park, with grass making up about two thirds. The deer have become so excessively numerous in Nara park, that there isn’t enough grass in the park for all of them to live entirely on grass, creating a dependency on humans for rice crackers. This lack of grass also causes the deer to resort to eating garbage and plants that they wouldn’t normally eat.[37] The deer in Nara park have become overpopulated due to being fed by people frequently, and having few predators. And the deer have caused extensive damage to trees (by feeding on bark,) bamboo (by eating their shoots,) and other plants in the park. Additionally, the deer have become aggressive towards humans in their solicitation of food (which leads to people getting injured by deer,) aggressive towards each other in competition for rice crackers, and have lost their fear of predators in general. For these reasons, tourists may want to consider not feeding the deer in Nara park, and simply observe them instead.[38][39]

- Gallery

Deer in Nara Park (2012).

Deer in Nara Park (2012). Deer approaching tourists in Nara Park in summer.

Deer approaching tourists in Nara Park in summer. Deer in Nara Park

Deer in Nara Park

Education

As of 2005, there are 16 high schools and 6 universities located in the city of Nara.

Universities

Nara Women's University is one of only two national women's universities in Japan. Nara Institute of Science and Technology is a graduate research university specializing in biological, information, and materials sciences.

Public schools

Public elementary and junior high schools are operated by the city of Nara.

Public high schools are operated by the Nara Prefecture.

Private schools

Private high schools in Nara include the Tōdaiji Gakuen, a private school founded by the temple in 1926.

Transportation

The main central station of Nara is Kintetsu Nara Station with JR Nara station some 500m west and much closer to Shin-Omiya station.

Rail

- West Japan Railway Company

- Kansai Main Line (Yamatoji Line): Narayama Station – Nara Station

- Sakurai Line (Manyō-Mahoroba Line): Nara Station – Kyōbate Station – Obitoke Station

- Kintetsu Railway

- Nara Line: Tomio Station – Gakuen-mae Station – Ayameike Station – Yamato-Saidaiji Station – Shin-Ōmiya Station – Kintetsu Nara Station

- Kyoto Line: Takanohara Station – Heijō Station – Yamato-Saidaiji Station

- Kashihara Line: Yamato-Saidaiji Station – Amagatsuji Station – Nishinokyō Station

- Keihanna Line: Gakken Nara-Tomigaoka Station

Roads

Twin towns – sister cities

International

Nara's sister cities are:[40]

.svg.png.webp) Canberra, Australia

Canberra, Australia Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea

Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea Toledo, Province of Toledo, Spain

Toledo, Province of Toledo, Spain Versailles, Yvelines, France

Versailles, Yvelines, France Xi'an, Shaanxi, China

Xi'an, Shaanxi, China Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China

Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China

Domestic

Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan

Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan Kōriyama, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan

Kōriyama, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan Obama, Fukui Prefecture, Japan

Obama, Fukui Prefecture, Japan Tagajō, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan

Tagajō, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan Usa, Ōita Prefecture, Japan

Usa, Ōita Prefecture, Japan

In popular culture

Nara is featured in the anime and manga, Tonikawa: Fly Me to the Moon.

Nara is the inspiring location for the 2014 album This Is All Yours by English indie rock band Alt-J

References

- "Population of Cities in Japan (2022)".

- 柳田国男 (Yanagita, Kunio) (1936): 地名の研究 (The Study of Place Names) Archived 2018-01-17 at the Wayback Machine, pub. 古今書院 (Kokon Shoin), pp. 217–219

- 東条 操 (Tōjō, Misao) (1951): 全国方言辞典 Dictionary of Japanese Dialects, 東京堂出版.

- "吉田東伍 YOSHIDA Tōgo (1907), 『大日本地名辞書 上巻』 (The Dictionary of Place Names in the Great Japan, Fuzambo, Vol.1), 冨山房, pp.190–191". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- 松岡静雄 編 MATSUOKA Shizuo ed. (1929), 『日本古語大辞典』 (The Unabridged Dictionary of Old Japanese), 刀江書院, p.955. Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Previous to Matsuoka, KANAZAWA Shôzaburô (1903) pointed out the possibility of influence from Korea. Both were, however, comparing Old Japanese to Modern Korean, not Old Korean.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1 November 1991). "Morphological clues to the relationships of Japanese and Korean". In Baldi, Philip (ed.). Patterns of Change – Change of Patterns: Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology. The Hague: De Gruyer Mouton. pp. 496–497. doi:10.1515/9783110871890. ISBN 978-3-11-013405-6. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- 楠原佑介ほか KUSUHARA Yūsuke et al. (1981), 『古代地名語源辞典』 (The Dictionary of Ancient Place Name Etymology), 東京堂出版, p.232

- One of the earliest assumption for this is seen in 奈良市 編 Nara ed. (1937), 『奈良市史』 (The History of Nara, Nara)., 奈良市.

- 宮腰賢ほか編 MIYAKOSHI Masaru et al. ed. (2011), 『全訳古語辞典』 (The Dictionary of Old Japanese with Complete Translation) 第4版, 旺文社.

- 池田末則・横田健一編 IKEDA Suenori & YOKOTA Ken'ichi (Eds.) (1981), 『日本歴史地名大系30 奈良県の地名』(A Series on Historical Place Names in Japan, Vol. 30, Place Names in Nara Prefecture), 平凡社, p.490

- 角川日本地名大辞典編纂委員会編 (1990), 『角川日本地名大辞典 29 奈良県』(Kadokawa Unabridged Dictionary of Place Names in Japan, Vol. 29, Nara Prefecture), 角川書店, p.814

- e.g. 斎藤建夫 編 SAITŌ Tateo (ed.) (1997), 『郷土資料事典 : ふるさとの文化遺産. 29(奈良県) 』 (The Dictionary of Native Place Data. Vol. 29. Nara Prefecture.), 人文社, p.27

- Ogata, Noboru. "Nara (Heijô-kyô) — The Capital of Japan in the eighth Century". Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Toby, Ronald (Autumn 1985). "Why Leave Nara?: Kammu and the Transfer of the Capital". Monumenta Nipponica. 40 (3): 331–347. doi:10.2307/2384764. JSTOR 2384764.

- Burnett Hall, Robert (December 1932). "The Yamato Basin, Japan". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 22 (4): 243–292. doi:10.1080/00045603209357109. JSTOR 2560778.

- Johnston, Norman (1969). "Nara: The Old Imperial Capital of Japan". The Town Planning Review. 40 (1): 331–347. doi:10.3828/tpr.40.1.e34hm24750840401. JSTOR 40102657.

- Ebrey, Patricia (2014). Modern East Asia: From 1600: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Wadsworth.

- Whitney Hall, John (2014). The Cambridge History of Japan, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- "Taihō code". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Ogata, Noboru (13 October 2004). "Asuka in Nara – Gangô-ji Monastery and the Old Town of Nara". Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Yamachika, Hiroyoshi. "Tourist Maps of Nara in the Edo Period". Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Nara Prefectural Government Tourism Bureau Tourism Promotion Division. "Historical Timeline of Nara". Visit Nara. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "Travel Tips – Official Nara Travel Guide". Official Nara Travel Guide. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "Stroll Around Naramachi (Town of Nara) | Nara Travelers Guide". narashikanko.or.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "Former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe assassinated while giving campaign speech". Channel NewsAsia. 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- DIY gun used to kill Japan's Abe was simple to make, analysts say, Reuters.com. Accessed 13 July 2022.

- "City Profile of Nara". Nara City. 2 April 2007. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2007. For more details and latest figures, navigate to the equivalent Japanese page at the official homepage "奈良市統計書「統計なら」平成17年版(2005年版) - 奈良市役所". Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- World Encyclopedia 1988.

- Kikuchi 1994.

- 奈良市統計書「統計なら」平成17年版(2005年版)(Nara City Statistics, Year 2005 Edition) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- "Official website of Nara city" (in Japanese). Japan: Nara City. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- 奈良のシカの歴史 [The history of deer in Nara] (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- "In Nara, Japan, the deer know their place: everywhere". Los Angeles Times. 2 April 2010. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "Oh, deer! Take the cutest selfie at Japan's Nara Park". The Globe and Mail. 8 October 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- "Are There Really Deer Everywhere In Nara Park?". Matcha. 4 April 2015. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- https://nara-edu.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=repository_action_common_download&item_id=12203&item_no=1&attribute_id=17&file_no=1

- "奈良公園のシカは栄養不足、観光客のせんべい頼り".

- "奈良の鹿は栄養失調? 鹿せんべい食えたらイイわけじゃない(田中淳夫) - エキスパート".

- "「姉妹都市」と「友好都市」". city.nara.lg.jp. Nara. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

External links

- Nara City official website

- The Official Nara Travel Guide

- Public junior high schools in Nara

Geographic data related to Nara at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Nara at OpenStreetMap