Nizari–Seljuk conflicts

By the late 11th century, the Shi'a sub-sect of Ismailism (later Nizari Ismailism) had found many adherents in Persia, although the region was occupied by the Sunni Seljuk Empire. The hostile tendencies of the Abbasid–Seljuk order triggered a revolt by Ismailis in Persia under Hassan-i Sabbah.

| Nizari–Seljuk conflicts | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

(Semi)-independent

| (Nizari) Ismailis of Persia and Syria | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| See list | See list | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Unknown | Outnumbered | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Minimal; many political and military elites were assassinated | Unknown; many in the massacres | ||||||||

| Many were lynched due to suspicion or accusation of being Ismaili or sympathizing with the Ismailis | |||||||||

Due to the increasingly significant socio-economic issues, the decentralization of the Seljuk government leading to inefficient army mobilization, and a unifying factor of religion in the provinces facilitating the swift spread of the revolt, the Seljuks were unable to quickly put down the revolt.

The conflict was characterized by the weaker Nizaris assassinating key opponents and employing impregnable strongholds, and the Seljuks massacring the Ismailis and their sympathizers.

Due to the Seljuks and Nizaris being unable to complete the war quickly, the Nizaris lost their momentum in the war leading to a stalemate on both sides. Combined with the Nizaris confined to heavily defended castles in unfavorable terrain, the Seljuks reluctantly accepted the independence of the Nizari state.

Sources

The bulk of the sources authored by the Nizaris was lost after the Mongol invasion and during the subsequent Ilkhanate period (1256–1335). Much of what is known about the Nizari history in Persia is based on the hostile Ilkhanate-era history works Tarikh-i Jahangushay (written by the scholar Ata-Malik Juwayni, who was present during the Mongol takeover of the Nizari castles), Zubdat at-Tawarikh (by Abd Allah ibn Ali al-Kashani), and Jami' at-Tawarikh (by Rashid al-Din Hamadani).[1]

Background

In the tenth century, the Muslim World was dominated by two powers: the Fatimid Caliphate ruled over North Africa and the Levant while the Seljuk Empire controlled Persia. The Fatimids were adherents of Ismailism, a branch of Shia Islam, and the Seljuks were Sunni Muslims.

By the final decades of the imamate (leadership of the Ismaili Muslim community) of the Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir Billah (r. 1036–1094), many people in Seljuk-ruled Persia had converted to the Fatimid doctrine of Ismailism, while the Qarmatian doctrine was declining. Apparently, the Ismailis of Persia had already acknowledged the authority of a single Chief Da'i (missionary) based in a secret headquarters in the Seljuk capital Isfahan. The Chief Da'i in the 1070s was Abd al-Malik ibn Attash, a Fatimid scholar who was respected even among Sunni elites.[2] He led a revolt in 1080 provoked by the increasingly severe Seljuk repressions of the Ismailis.[3]

History

Establishment of the Alamut State

The Ismailis in Persia, including Da'i Hassan-i Sabbah, were aware of the declining power of the Fatimids during the final decades of the imamate of al-Mustansir.[4] Hassan was a new Ismaili convert who had been appointed to a post in the da'wah organization by Ibn Attash in May–June 1072. Within nine years of his missionary activity in several Seljuk provinces, Hassan had evaluated the strengths and weaknesses of the Seljuk military and government and took note of the Seljuk administrative and military prowess. After nine years of intelligence operations, Hassan concentrated his missionary efforts in Daylam, a traditional stronghold for the minority Zaydi Shias which had already been penetrated by the Ismaili da'wa.[5]

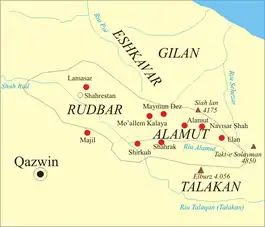

By 1087, Hassan had chosen the inaccessible castle of Alamut, located in the remote area of Rudbar (nowadays called "Alamut") in northern Persia, as the base of operations. From Damghan and later Shahriyarkuh, he dispatched several da'is to convert the locals of the settlements in the Rudbar valley near the castle. These activities were noticed by the Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk, who ordered Abu Muslim, the governor of Rayy, to arrest the da'i. Hassan managed to remain hidden and secretly arrived at Daylam, temporarily settling in Qazvin. He was later appointed as the Fatimid Da'i of Daylam.[6]

From Qazvin Hassan dispatched one further da'i to Alamut. Meanwhile, Ismailis from elsewhere infiltrated and populated the region near Alamut. Hassan then moved to Ashkawar, and then Anjirud, gradually getting closer to the castle, and secretly entered the castle itself on the eve of September 4, 1090, living there for a while disguised as a children's teacher. Mahdi, the commandant of the castle, eventually discovered Hassan's identity, but he was powerless since many in the castle, including his guards, were Ismailis or Ismaili converts then. Hassan permitted Mahdi to leave peacefully and then paid him via Muzaffar, a Seljuk ra'is and a secret Ismaili, 3,000 gold dinars for the castle. The seizure of the castle marks the establishment of the Ismaili state in Persia (also called the "Alamut state") and the beginning of the so-called Alamut Period during which the Ismaili mission unfolded as an open revolt against the Sunni authorities.[7]

Expansion in Rudbar and Quhistan

The Ismailis of Alamut quickly began to construct or capture (by conversion or force) new strongholds in Rudbar valley on the bank of the Shahrud river.[8] Meanwhile, Hassan dispatched Husayn Qa'ini to his homeland, Quhistan (a region southwest of Khurasan), where he was more successful. The Quhistani people resented the rule of their oppressive Seljuk emir more, such that the movement spread there not through secret conversion, but an open revolt. Soon the major towns of Tun (modern Ferdows), Tabas, Qa'in, and Zuzan came under Ismaili control. Quhistan became a well-established Ismaili province governed by a local ruler, titled muhtasham, appointed from Alamut.[9]

The areas that had been chosen by the Ismaili leaders (Rudbar, Quhistan, and later Arrajan) had several common advantages: difficult mountainous terrains, dissatisfied populations, and local traditions of Ismaili or at least Shia tendencies.[10] Initially, the Ismailis gained support mostly in rural areas. They also received crucial support from non-Ismailis who sympathized with them due to socio-economic or political reasons. Thus, the Ismailis transformed into a formidable and disciplined revolutionary group against the staunchly Sunni Abbasid–Seljuk order that had dominated the Islamic World.[11]

A complex set of religious and political motives was behind the revolt. The anti-Shia policies of the Seljuks, the new pioneers of Sunni Islam (see Sunni Revival), were not tolerable for the Ismailis. The early widespread Ismaili revolt in Persia was, less conspicuously, an expression of national Persian Muslim sentiment:[12] the Persians, who had been Islamized but not Arabized,[13] were conscious of their distinct identity in the Muslim World and viewed the Seljuk Turks (and their Turkish predecessors Ghaznavids and Qarakhanids which had put an end to the so-called Iranian intermezzo)[14] as foreigners who had invaded their homeland from Central Asia.[3] Seljuk rule was detested by multiple social classes. Hassan himself openly resented the Turks. The Ismaili state was the first Muslim entity that adopted Persian as a religious language.[15]

Economic issues further contributed to the widespread revolt. The new Seljuk social order was based on iqta' (allotted land), which subjugated the locals under a Turkic emir and his army that levied heavy taxes. In contrast, the Ismaili state was dedicated to the ideal of social justice.[16]

Early Seljuk responses

The first bloodshed perpetrated by the Ismailis against the Seljuks was possibly before the capture of Alamut. A group of Ismailis performing joint prayers was arrested in Sawa by the Seljuk police chief and were freed after being questioned. The group later unsuccessfully attempted to convert a muezzin from Sawa who was active in the Seljuk capital Isfahan. Fearing that he would denounce Ismailism, the group murdered the muezzin. The vizier Nizam al-Mulk ordered the execution of the group's leader, Tahir, whose corpse was then dragged through the market. Tahir was a son of a senior preacher who had been lynched by a mob in Kirman for being an Ismaili.[10]

Yurun-Tash, the emir holding the iqta' of Rudbar, quickly began to harass and massacre the Ismailis at the foot of Alamut. The besieged garrison of Alamut was on the verge of defeat and was considering abandoning the castle due to a lack of supplies. However, Hassan claimed that he had received a special message promising good fortune from Imam al-Mustansir Billah, persuading the garrison to continue their resistance. The Ismailis eventually emerged victorious when Yurun-Tash died of natural causes. Alamut was nicknamed baldat al-iqbāl (lit. 'the city of good fortune') after this victory.[17][18]

Campaigns of Sultan Malikshah and Nizam al-Mulk

Sultan Malikshah and his vizier Nizam al-Mulk soon realized the inability of the local emirs to manage the Ismaili rebels. In 1092, they sent two separate armies against Rudbar and Quhistan. The garrison of Alamut consisted of only 70 men with limited supplies when the Seljuk army under emir Arslan-Tash invested the castle. Hassan asked for assistance from the Qazvin-based da'i Dihdar Abu Ali Ardestani. The latter broke the Seljuk line with a force of 300 men and resupplied and reinforced Alamut. A coordinated surprise attack in September or October 1092 by the reinforced garrison and allied locals resulted in a rout of the Seljuk besiegers.[19]

While planning further anti-Ismaili campaigns, Nizam al-Mulk was assassinated on October 14, 1092, in western Persia. The assassination was performed by a fida'i sent by Hassan-i Sabbah, but it was probably at the instigation of Sultan Malikshah and his wife Terken Khatun, who were wary of the all-powerful vizier.[21]

Meanwhile, the Seljuk army against Quhistan, led by emir Qizil-Sarigh and supported by forces from Khorasan and Sistan, was concentrating its efforts on the castle of Darah, a dependency of the major Ismaili castle of Mu'min-Abad.[22] Sultan Malikshah died in November 1092 and the soldiers besieging Darah immediately withdrew because the Seljuk soldiers traditionally owed their allegiance only to the sultan himself. With the deaths of Nizam al-Mulk and Malikshah, all planned actions against the Ismailis were aborted.[23]

[The assassination of Nizam al-Mulk] was the first of a long series of such attacks which, in a calculated war of terror, brought sudden death to sovereigns, princes, generals, governors, and even divines who had condemned Nizari doctrines and authorized the suppression of those who professed them.

Further Ismaili expansion and schism during the Seljuk civil war of 1092–1105

The sudden deaths of Nizam al-Mulk and Malikshah reshaped the political landscape of the Seljuk realm. A decade-long civil war began involving the Seljuk claimants and the semi-independent Seljuk emirs who constantly shifted their allegiances. Barkiyaruq had been proclaimed as the ruler, supported by the relatives of Nizam al-Mulk and the new Abbasid caliph al-Mustazhir. His rivals included his half-brother Muhammad Tapar and Tutush, the governor of Syria. The latter was killed in 1095 in battle. Fighting with Muhammad Tapar, who was backed by Sanjar, was indecisive, however.[24]

Exploiting this political ferment and the power vacuum that developed, the Ismailis consolidated and expanded their positions into many places such as Fars, Arrajan, Kirman, and Iraq, often with temporary help from Seljuk emirs.[25][26] Filling the power vacuum following diminished authority of a Seljuk sultan in an area became the regular pattern of Nizari territorial expansion during these conflicts.[26] Hassan made Alamut as impregnable as possible. Assisted by local allies, new fortresses were seized in Rudbar. In 1093, the Ismailis took the village of Anjirud and repulsed an invading force there. In the same year, a 10,000-strong army consisting mostly of Sunnis from Rayy and commanded by the Hanafi scholar Za'farani was defeated in Taliqan. Soon another raid by the Seljuk emir Anushtagin was also repulsed. As a result of these Nizari victories, the local chiefs of Daylam gradually shifted their allegiance to the nascent Alamut state. Among these was a certain Rasamuj who held the strategic Lamasar castle near Alamut. He later tried to defect to Anushtagin, but in November 1096 (or 1102, per Juwayni) an Ismaili force under Kiya Buzurg-Ummid, Kiya Abu Ja'far, Kiya Abu Ali, and Kiya Garshasb attacked the castle and captured it. Hassan appointed Buzurg-Ummid as Lamasar's commandant, who expanded it into the largest Ismaili fortress.[27]

In 1094, the Fatimid Caliph-Imam al-Mustansir died and his vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah quickly placed the young al-Musta'li on the Fatimid throne, who was subsequently recognized as the Imam by the Ismailis under Fatimid influence (i.e. those of Egypt, much of Syria, Yemen, and western India). However, al-Mustansir had originally designated Nizar as his heir. As a result, the Ismailis of the Seljuk territories (i.e. Persia, Iraq, and parts of Syria), now under the authority of Hassan, severed the already weakened ties with the Fatimid organization in Cairo and effectively established an independent da'wa organization of their own on behalf of the then-inaccessible Nizari Imams.[note 1][28] In 1095, Nizar's revolt was crushed in Egypt and he was imprisoned in Cairo. Further revolts by his offspring were also unsuccessful. Apparently, Nizar himself had not designated any successor. Hassan was recognized as the hujja (full-representative) of the then-inaccessible Imam. Rare Nizari coins from Alamut belonging to Hassan and his two successors bear the name of an anonymous descendant of the Nizar.[29]

In 1095, the Seljuk vizier al-Balasani, who was a Twelver Shia, entrusted the citadel of Takrit in Iraq to the officer Kayqubad Daylami, an Ismaili. The citadel, one of the few open Nizari strongholds, remained in their hands for 12 years (al-Balasani was later lynched by the Seljuks).[31] Many new scattered strongholds were also seized, including Ustunawand in Damavand and Mihrin (Mihrnigar), Mansurkuh, and the strategic Girdkuh in Qumis, situated on the Great Khorasan Road.[32] Gerdkuh was acquired and refortified by the Seljuk ra'is Muzaffar, a secret Ismaili convert and lieutenant of emir Habashi, who in turn had acquired the fort in 1096 from Sultan Barkiyaruq. The latter never enjoyed a reputation of being a defender of Sunnis and hence expediently incorporated Ismailis in his forces at times of dire necessity. In 1100, near Girdkuh, 5,000 Ismailis from Quhistan and elsewhere under ra'is Muzaffar fought alongside Habashi and Barkiyaruq against Sanjar; Habashi was killed and Muzaffar later transferred the former's treasure to Girdkuh and, after completing the fortifications, publicly declared himself an Ismaili and transferred the fortress into Nizari possession in the same year.[33][34] Abu Hamza, another Ismaili da'i from Arrajan who had been a shoemaker studied in Fatimid Egypt, returned home and seized at least two nearby castles in his small but important home province south of Persia.[35]

The Nizaris were successful during the reign of Barkiyaruq, especially after 1096. Besides consolidating their positions and seizing new strongholds, they spread the da'wa into the towns as well as Barkiyaruq's court and army, thereby directly meddling in Seljuk affairs. Despite assassination attempts against Barkiyaruq himself, the opposing Seljuk factions often blamed him for the assassination attempts against their officers and accused all Barkiyaruq's soldiers of subscribing to Ismailism.[36] By 1100, the da'i Ahmad ibn Abd al-Malik, the son of the prominent da'i Abd al-Malik ibn Attash, captured the strategic fortress of Shahdiz just outside the Seljuk capital Isfahan. Ahmad reportedly converted 30,000 people in the region and began collecting taxes from several nearby districts. A second fortress, Khanlanjan (Bazi) located south of Isfahan was also seized.[37]

In response to growing Nizari power, Barkiyaruq reached an agreement with Sanjar in 1101 to exterminate all Nizaris in their subordinate regions, i.e. western Persia and Khurasan, respectively. Barkiyaruq supported massacres of the Nizaris in Isfahan and purged his army by executing suspected Ismaili officers,[38] while the Abbasid caliph al-Mustazhir persecuted suspected Nizaris in Baghdad and killed some of them, as requested by Barkiyaruq.[39] Meanwhile, Sanjar's campaign commanded by emir Bazghash against Quhistan caused much damage to the region. In 1104, another campaign in Quhistan destroyed the city of Tabas and many Nizaris were massacred; however, no stronghold was lost and the Nizaris maintained their overall position; in fact, in 1104–1105, the Nizaris of Turshiz campaigned as far west as Rayy.[40] The Nizaris expanded into Kirman too, and even won the Seljuk ruler of Kerman, Iranshah ibn Turanshah (1097–1101). Prompted by the local Sunni ulama (Islamic scholars), the townspeople soon deposed and executed him.[41]

Nizari mission in Syria

Most Ismailis of Syria had originally recognized al-Musta'li as their Imam (see above). However, the vigorous Nizari da'wa soon replaced the doctrine of the declining Fatimids there, particularly in Aleppo and the nearby Jazr region, such that the Syrian Musta'li community was reduced to an insignificant element by 1130.[42] Nevertheless, the Nizari mission in Syria proved to be more challenging than in Persia: their fledgling presence in Aleppo and later Damascus was soon eliminated, and they acquired a cluster of mountain strongholds only after a half-century of continuous efforts. The methods of struggle of the da'is in Syria were the same as those in Persia: acquiring strongholds as bases for activity in the nearby areas, selective elimination of prominent enemies, and temporary alliances with various local factions, including Sunnis and the Crusaders, to reach objectives.[43]

Background

Nizari activity in Syria began in the early years of the 12th century or a few years earlier in the form of da'is dispatched from Alamut. Tutush I's death in 1095 and Frankish Crusader advances in 1097 caused Syria to become unstable and politically fragmented into several rival states. The decline of the Fatimids after al-Mustansir Billah's death coupled with the aforementioned political confusion of Seljuks and the Crusader threats all urged Sunnis and Shias (including Musta'lis and non-Ismailis such as Druzes and Nusayris) to shift their allegiance to the Nizari state, which boasted its rapid success in Persia.[44]

Rise and fall in Aleppo

The first phase of Nizari activity lasted until 1113. Under the da'i al-Hakim al-Munajjim, the Nizaris allied with Ridwan, the emir of Aleppo who was a key political figure in Syria along with his brother Duqaq, the emir of Damascus. The da'i even joined Ridwan's entourage, and the Aleppine Nizaris established a Mission House (dar al-dawah) in the city, operating under Ridwan's aegis. One of their military actions was the assassination of Janah ad-Dawla, the emir of Hims and a key opponent of Ridwan.[45]

Al-Hakim al-Munajjim died in 1103 and was replaced by the da'i Abu Tahir al-Sa'igh, also sent by Hassan-i Sabbah. Abu Tahir enjoyed an alliance with Ridwan as well and continued using the Nizari base in Aleppo. He attempted to seize strongholds in pro-Ismaili areas, especially the Jabal al-Summaq highlands located between the Orontes River and Aleppo. The authority over the upper Orontes valley was being shared between the assassinated Janah al-Dawlah, the Munqidhites of Shayzar, and Khalaf ibn Mula'ib, the Fatimid governor of Afamiyya (Qal'at al-Mudhiq) who had seized the fortified city from Ridwan. Khalaf was probably a Musta'li that had refused the Nizari alliance. Abu Tahir, with the help of local Nizaris under a certain Abu al-Fath of Sarmin, assassinated Khalaf in February 1106 and acquired the citadel of Qal'at al-Mudhiq by an "ingenious" plan. Tancred, the Frankish regent of Antioch besieged the city, but he was unsuccessful. A few months later in September 1106, he besieged the city again and captured it with the help of Khalaf's brother, Mus'ab. Abu al-Fath was executed, but Abu Tahir ransomed himself and returned to Aleppo.[46][47]

In 1111, Nizari forces joined Ridwan as he closed Aleppo's gate to the expeditionary force of Mawdud, the Seljuk atabeg of Mosul, who had come to Syria to fight the Crusaders. However, in his final years, Ridwan retreated from his earlier alliances with the Nizaris due to the determined anti-Nizari campaign of Muhammad Tapar (see below) coupled with the increasing unpopularity of the Nizaris among the Aleppines.[note 2] Mawdud was assassinated in 1113, but it is uncertain who was actually behind it.[46][48]

Ridwan died shortly after and his young son and successor Alp Arslan al-Akhras initially supported the Nizaris, even ceding the Balis fortress on the Aleppo–Baghdad road to Abu Tahir. Soon Alp Arslan was turned against the Nizaris by Muhammad Tapar, who had just begun an anti-Nizari campaign, as well as Sa'id ibn Badi', the ra'is of Aleppo and militia (al-ahdath) commander. In the subsequent persecution led by Sa'id, Abu Tahir and many other Nizaris in Aleppo were executed[note 3] and others dispersed[note 4] or went underground.[46][49] An attempt by the regrouped Nizaris of Aleppo and elsewhere to seize the Shayzar castle was defeated by the Munqidhites.[50]

Although the Nizaris failed to establish a permanent base in Syria, they managed to establish contacts and convert many locals.[51]

Rise and fall in Damascus

After the execution of his predecessor Abu Tahir al-Sa'igh and the uprooting of the Nizaris in Aleppo, Bahram al-Da'i was sent by Alamut in an attempt to resurrect the Nizari cause in Syria.[46] In 1118, Aleppo was captured by Ilghazi, the Artuqid prince of Mardin and Mayyafariqin. The Nizaris of Aleppo demanded Ilghazi cede to them a small castle called Qal'at al-Sharif, but Ilghazi had the castle demolished and pretended that the order was given earlier. The demolition was conducted by qadi Ibn al-Khashshab, who had been earlier involved in a massacre of the Nizaris (he was later assassinated by the Nizaris in 1125). In 1124, Ilghazi's nephew Balak Ghazi, the (nominal) governor of Aleppo, arrested Bahram's representative there and expelled the Nizaris.[52]

Bahram focused on Southern Syria as recommended by his supporter, Ilghazi. The da'i resided there in secret and practiced his missionary activities in disguise. Supported by Ilghazi, he managed to obtain the official protection of the Burid ruler Tughtigin, atabeg of Damascus, whose vizier al-Mazadaqani had become a reliable Nizari ally. At this point in 1125, Damascus was under threats of the Frankish Crusaders under Baldwin II of Jerusalem, and Ismailis from Homs and elsewhere had earlier joined Tughtigin's troops and had been noted for their courage in the Battle of Marj al-Saffar against the Franks in 1126.[53][54] Moreover, Bahram had probably helped in the assassination of Tughtigin's enemy Aqsunqur al-Bursuqi, the governor of Mosul. Therefore, Toghtekin welcomed Bahram and his followers. Al-Mazadaqani persuaded Toghtekin to give a Mission House in Damascus and the frontier stronghold Banias to Bahram, who refortified it and made it his military base, performing extensive raids from there and possibly capturing more places. By 1128, their activities had become so formidable that "nobody dared to say a word about it openly".[53][55]

Bahram was killed in 1128 while fighting local hostile tribes in Wadi al-Taym.[56][53] The Fatimids in Cairo rejoiced after receiving his head.[57] He was succeeded by Isma'il al-Ajami who kept using Banias and following his predecessor's policies. Tughtigin's successor and son, Taj al-Muluk Buri, initially continued to support the Nizaris, but, in a repetition of the events of 1113 in Aleppo, he was instigated by his advisors at the right moment to shift his policy, killing al-Mazdaqani and ordering a massacre of all Nizaris, which was conducted by al-ahdath (militia) and the Sunni population. Around 6,000 Nizaris were killed.[note 5][58] Ismail al-Ajami surrendered Banias to the advancing Franks during their Crusade of 1129 and died in exile among the Franks in 1130. Despite elaborate security measures taken by Buri, he was struck in May 1131 by fida'is from Alamut and died of his wounds a year later. Nevertheless, the Nizari position in Damascus was already lost forever.[59]

Sultan Muhammad Tapar's campaigns

Barkiyaruq died in 1105. Due to this, Muhammad Tapar, along with Sanjar who acted as his eastern viceroy, became the unchallenged Seljuk sultan who ruled the stabilized empire until 1118.[60][10] Although their expansion had been checked by Barkiyaruq and Sanjar, the Nizaris still held their ground and threatened the Seljuk lands from Syria to eastern Persia, including their capital of Isfahan. Naturally, the new sultan regarded the war against the Nizaris as an imperative.[61]

Muhammad Tapar launched a series of campaigns against the Nizaris and checked their expansion within two years after his accession. A Seljuk siege against Takrit failed to capture the citadel after several months, but the Nizaris under Kayqubad were also unable to keep it and ceded it to an independent local Twelver Shia Arab ruler, the Mazyadid Sayf al-Dawla Sadaqa. At the same time, Sanjar attacked Quhistan, but the details are unknown.[62]

Muhammad Tapar's main campaign was against Shahdiz which was threatening his capital Isfahan. He eventually captured Shahdiz in 1107 after a siege involving many negotiations;[26] some of the Ismailis safely withdrew per an agreement, while a small group kept fighting. Their leader, Da'i Ahmad ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Attash, was captured and executed together with his son. The fortress of Khanlanjan was probably destroyed too, and the Ismaili presence in Isfahan was brought to an end. Muhammad Tapar issued a fathnama (victory proclamation) after the capture of Shahdiz.[26] Probably soon after destroying Shadiz, Seljuk forces under Muhammad Tapar's atabeg of Fars, Fakhr al-Dawla Chawli, destroyed the Nizari fortresses in Arrajan[63] in a surprise attack as he pretended to be preparing for an attack against his neighbor Bursuqids.[64] Little is recorded about Nizaris in the area after this event.[65]

In 1106-1109, Muhammad Tapar sent an expeditionary force under his vizier Ahmad ibn Nizam al-Mulk (whose father Nizam al-Mulk and brother Fakhr al-Mulk had been assassinated by the Nizaris), accompanied by Chawli, against the Nizari heartland of Rudbar. The campaign devastated the area but failed to capture Alamut, and the Seljuks withdrew. Muhammad Tapar unsuccessfully attempted to receive assistance from the Bavandid ruler Shahriyar IV ibn Qarin.[66][10] In 1109, Muhammad Tapar began another campaign against Rudbar. The Seljuks had realized the impregnability of Alamut to a direct assault, so they began a war of attrition by systematically destroying the crops of Rudbar for eight years and engaging in sporadic battles with the Nizaris. In 1117/1118, the atabeg Anushtagin Shirgir, the governor of Sawa, took up the Seljuk command and began the sieges of Lamasar on June 4 and Alamut on July 13. The Nizaris were in a difficult position. Hassan-i Sabbah and many others sent their wives and daughters to Girdkuh and elsewhere.[note 6] The Nizari resistance surprised their adversary, which was being continually reinforced by other emirs. In April 1118, the Seljuk forces were once again on the verge of victory when the news of Muhammad Tapar's death caused them to withdraw. Many Seljuks were killed in the retreat and the Nizaris obtained many supplies and weapons.[67] The Seljuk vizier Abu al-Qasim Dargazini, who was allegedly a secret Nizari, procured the new sultan Mahmud II to withdraw the forces of Anushtagin, and turned the sultan against Anushtagin, who had the latter imprisoned and executed.[10]

Muhammad Tapar's campaign ended in a stalemate. The Seljuks failed to reduce the Nizari strongholds, while the Nizari revolt lost its initial effectiveness.[68][69] Unable to repel the concerted Seljuk campaigns, the Nizaris had continued to rely on assassinating important Seljuk leaders, such as Ubayd Allah ibn Ali al-Khatibi (qadi of Isfahan and the leader of the anti-Ismaili movement there) in 1108-1109, Sa'id ibn Muhammad ibn Abd al-Rahman (qadi of Nishapur), and other bureaucrats and emirs. Ahmad ibn Nizam al-Mulk, who led the expedition against Alamut, survived an assassination attempt in Baghdad, though he was wounded.[26][10] In 1116/1117, the Seljuk emir of Maragha, Ahmadil ibn Ibrahim al-Kurdi, was assassinated by the Nizaris in a large assembly in presence of Sultan Muhammad Tapar—a blow to the prestige of the Seljuks.[70]

Stalemate

The Nizaris used an opportunity to recover during another destructive civil war among the Seljuks after Muhammad Tapar's death.[10]

For the rest of the Seljuk period, the situation was a stalemate and a tacit mutual acceptance emerged between the Nizaris and the Sunni rulers. The great movement to establish a new millennium in the name of the hidden Imam had been reduced to regional conflicts and border raids, and the Nizari castles had been turned into centers of small local sectarian dynasties. Seljuk campaigns after Muhammad Tapar's death were mostly half-hearted and indecisive, while the Nizaris lacked the initial strength to repeat successes such as the capture of Shahdiz. The Seljuk sultans did not consider the Nizaris, who were now mostly in remote fortresses, a threat to their interests. The Seljuks even used the Nizaris for their assassinations, or at least used their notoriety for the use of assassination to cover up their own assassinations; such as those of Aqsunqur al-Ahmadili and the Abbasid Caliph al-Mustarshid in 1135, probably by Sultan Mas'ud.[10][26] The number of the recorded assassinations dwindles after Hassan-i Sabbah's reign.[10] The Nizaris eventually abandoned the tactic of assassination, because political terrorism was considered reprehensible by the common people.[71]

The nature of Nizari–Seljuk relations gradually changed in this period: the Seljuqs no longer repudiated the Nizari mission, but the Nizari presence in inner Seljuk territories was brought to an end and they began to focus on consolidating their remote territories instead. Small (semi)-independent Nizari states were established, which busied themselves with local alliances and rivalries.[10]

Reigns of Mahmud II and Sanjar

Muhammad Tapar was succeeded by his son Mahmud II (r. 1118–1131), who ruled over western Persia and (nominally) Iraq, but he faced many claimants. Sanjar, who held Khorasan since 1097, was generally recognized as the head of the Seljuk family.[72] The Nizaris maintained peaceful or friendly relations with Sanjar. According to Juwayni, Sanjar was prompted into these good ties after Hassan-i Sabbah had a eunuch place a dagger beside Sanjar's bed while he was asleep. Several manshurs (decrees) by Sanjar are recorded in the library of Alamut, in which the sultan had conciliated the Nizaris. Sanjar reportedly paid the Nizaris an annual of 3,000-4,000 dinars from taxes of Qumis and allowed them to levy tolls from the caravans passing beneath Girdkuh on the Khurasan Road. The peaceful final years of Hassan-i Sabbah, which were mostly spent consolidating the Nizari position, including the recapture of strongholds in Rudbar that had been lost in Shirgir's campaign, as well as intensifying the da'wa in Iraq, Adharbayjan, Gilan, Tabaristan, and Khurasan, is partly attributed to the Nizari ties with Sanjar.[73] Some Nizaris joined Sanjar's forces in his invasion of Mahmud II's territories in 1129. Mahmud II was defeated in Sawa and most of northern Persia, including Tabaristan and Qumis, which was penetrated by the Nizaris, came under Sanjar's rule. Mahmud II's brother, Tughril, later rebelled and took Gilan, Qazvin, and other districts.[74]

Campaigns against Kiya Buzurg-Ummid

In 1126, two years after Kiya Buzurg-Ummid succeeded Hasan Sabbah as the head of the Alamut state, Sanjar sent his vizier Mu'in al-Din Ahmad al-Kashi to attack the Nizaris of Quhistan with orders to massacre them and confiscate their properties. The casus belli is uncertain; it may have been motivated by a perceived weakness of the Nizaris after Hassan's death. The campaign ended with limited success. In Quhistan, a Seljuk victory in the village of Tarz (near Bayhaq) and a successful raid on Turaythith have been recorded. In the same year, Mahmud sent an army led by Shirgir's nephew, Asil, against Rudbar; this campaign was even less successful and was repelled. Another Seljuk campaign launched with local support against Rudbar was also defeated and a Seljuk emir, Tamurtughan, was captured. He was released later as requested by Sanjar. At the same time or shortly after the campaign in Quhistan, the Nizaris lost Arrajan; after this point, little is recorded about them in Arrajan and, consequently, in Khuzestan and Fars also.[10][75] The Nizaris were quick to take revenge—the commander of the Quhistan's campaign, vizier al-Kashi, was assassinated in March 1127 by two fida'is who had infiltrated into his household.[note 7][10][76]

At the end of Buzurg-Ummid's reign in 1138, the Nizaris were stronger than before. Several fortresses (including Mansur) were captured in Taliqan, while several new ones were constructed, including Sa'adatkuh and most famously the major stronghold of Maymun-Diz in Rudbar. In 1129, the Nizaris (presumably of Quhistan) mobilized an army and raided Sistan.[77] In May of the same year, Mahmud moved to make peace by inviting an envoy from Alamut. The envoy, Khwaja Muhammad Nasihi Shahrastani, and his colleague were lynched by a mob in Isfahan after visiting Mahmud. The latter apologized but refused Buzurgummid's request to punish the murderers. In response, the Nizaris attacked Qazvin, killing some and taking much booty; when the Qazvinis fought back, the Nizaris assassinated a Turkish emir, resulting in their withdrawal. This conflict marked the beginning of a long-lasting feud between the Qazvinis and the Nizaris of Rudbar. Mahmud also launched an abortive attack on Alamut. Another army sent from Iraq against Lamasar similarly failed to achieve results.[10][78]

Sultan Mas'ud, Muhammad ibn Buzurg-Ummid, and later lords of Alamut

In 1131, Mahmud II died and another dynastic struggle commenced. Some of the emirs involved the Abbasid caliph al-Mustarshid (r. 1118–1135) in the conflicts against Sultan Mas'ud (r. 1133–1152). In 1135 or 1139, Mas'ud captured the caliph, together with his vizier and several dignitaries, near Hamadan, treated him with respect, and brought him to Maragha. However, while the caliph and his companions were in the royal tentage, he let a large group of Nizaris enter the tent and assassinate al-Mustarshid and his companions. Rumors arose suggesting the involvement (or deliberate negligence) of Mas'ud and even Sanjar (the nominal ruler of the empire). In Alamut, celebrations were held for seven days.[10][79][80] The governor of Maragha was also assassinated shortly before the arrival of the caliph. Several other Seljuk elites were also assassinated during the reign of Kiya Buzurg-Ummid in Alamut, including a prefect of Isfahan, a prefect of Tabriz, and a mufti of Qazvin, though the number of assassinations was considerably less than those ordered during Hassan Sabbah's reign.[10]

Al-Mustarshid's son and successor, al-Rashid (r. 1135–1136), also became involved in the Seljuk dynastic conflicts, and after being deposed by an assembly of Seljuk judges and jurists, was assassinated by the Nizaris in 5 or 6 June 1138 when he arrived in Isfahan to join his allies. In Alamut, celebrations were held again for the death of a caliph and the first victory for the new Lord of Alamut, Muhammad ibn Buzurg-Ummid. In Isfahan, a great massacre of the Nizaris (or those accused to be Nizaris) was committed. During the reign of Muhammad ibn Buzurg-Ummid, the Seljuk sultan Da'ud, who had persecuted the Nizaris of Adharbaijan, was assassinated in Tabriz in 1143 by four Syrian fida'is. They were allegedly sent by Zangi, the ruler of Mosul, who feared that Da'ud may depose him. An attack by Mas'ud against Lamasar and other places in Rudbar was repelled in the same year.[10][81][82]

Nizari activity expanded to Georgia (where a local ruler was assassinated) and their territories were expanded into Daylam and Gilan, where new fortresses, namely Sa'adatkuh, Mubarakkuh, and Firuzkuh were captured chiefly through the efforts of the commander Kiya Muhammad ibn Ali Khusraw Firuz. Nizari operations were often led by Kiya Ali ibn Buzurg-Ummid, a brother of Muhammad. They also attempted to penetrate the empire of Ghur (in present-day Afghanistan).[10][83]

Other assassinations recorded during Muhammad's reign include an emir of Sanjar and one of his associates, Yamin al-Dawla Khwarazmshah (a prince of the Khwarazmian dynasty, in 1139/1140), a local ruler in Tabaristan, a vizier, and the qadis of Quhistan (in 1138/1139), Tiflis (in 1138/1139), and Hamadan (in 1139/1140), who had authorized the executions of Nizaris. Nevertheless, the stalemate mostly continued during Muhammad ibn Buzurg-Ummid's reign.[10][84] The reduced number of assassinations during Muhammad's reign stemmed from the Nizaris' preoccupation with building fortresses and handling local conflicts with neighboring territories, in particular raids and counterraids between the Nizari heartland and neighboring Qazvin. Two notable regional enemies of the Nizaris in this period were the Bawandid ruler of Tabaristan and Gilan, Shah Ghazi Rustam (after the assassination of his son Girdbazu), and the Seljuk governor of Rayy, Abbas, both of whom were alleged to have built towers made of the skulls of Nizaris they massacred. Abbas was killed on Mas'ud's order and at Sanjar's request after an entreaty made by a Nizari emissary; this suggests another period of truce between Sanjar and the Nizaris. Elsewhere conflicts were reported with Sanjar, including the latter's attempt to restore Sunni Islam in a Nizari base in Quhistan: al-Amid ibn Mansur (or ibn Mas'ud), the governor of Turaythith, had submitted to the Quhistani Nizaris, but his successor Ala al-Din Mahmud appealed to Sanjar for restoring the Sunni rule there. Sanjar's army led by emir Qajaq was defeated. Soon after, another emir of Sanjar, Muhammad ibn Anaz, began to conduct personal raids against the Nizaris of Quhistan, though probably with Sanjar's approval, until at least 1159, i.e., after Sanjar's death. In Nizari castles, the leadership was often dynastic and hence the nature of most such conflicts is limited to that certain dynasty.[10][85]

%252C_minted_in_Alamut.jpg.webp)

The reigns of Hassan II and his son Muhammad II at Alamut were mostly peaceful, except some raids and the assassination of Adud al-Din Abu al-Faraj Muhammad ibn Abdallah, the prominent vizier of the Abbasid caliph al-Mustadi (r. 1170–1180), in 1177/1178, shortly after the toppling of the Fatimids by Saladin six years earlier.[10]

Nizari foothold in Jabal Bahra', Syria

As the Fatimid Caliphate declined soon after the Nizari–Musta'li schism, the bulk of the Ismailis of Syria rallied toward the Nizaris.[86] In this third phase of their activity in Syria from 1130 until 1151, the Nizaris obtained and held several strongholds in Jabal Bahra' (the Syrian Coastal Mountain Range).[87] After the Crusaders' failure to capture Jabal Bahra', the Nizaris had quickly reorganized under the da'i Abu al-Fath and transferred their activities from the cities to this mountainous region. Little is known about this period of the Nizaris in Syria. They obtained their first fortress, al-Qadmus, by purchasing it in 1132–1133 from the governor of al-Kahf Castle, Sayf al-Mulk ibn 'Amrun. Afterward, al-Kahf was also sold to the Nizaris by Sayf al-Mulk's son, Musa, to prevent the castle's fall to his rival cousins. In 1136–1137, the Crusader-occupied Khariba castle was captured by local Nizaris. In 1140–1141, the Nizaris captured Masyaf by killing Sunqur, who commanded the fort on behalf of the Munqidhites of Shayzar. The fortresses of Khawabi, Rusafa, Maniqa, and Qulay'a were captured around the same time. The 12th-century chronicler William of Tyre counted ten Nizari castles with a population of 60,000.[88]

The Nizaris' enemies at this point were the local Sunni rulers and the Crusader states of Antioch and Tripoli, and the Turkish governors of Mosul; the last controlled the strategic region between the Nizari centers in Syria and Persia. In 1148, the Zengid emir of Aleppo, Nur al-Din, abolished Shia prayer in Aleppo, which was considered an act of war against the Ismailis and other Shia Aleppines. A year later, a Nizari contingent assisted Prince Raymond of Antioch in his campaign against Nur al-Din; both Raymond and the Nizari commander Ali ibn Wafa' were killed in the subsequent battle at Inab in June 1149.[89]

A succession dispute occurred after the death of Shaykh Abu Muhammad, the head of the Nizari da'wa in Syria. Eventually, the leadership was passed to Rashid al-Din Sinan by orders from Alamut. He managed to consolidate the Nizari position in Syria against the Crusaders, Nur al-Din, and Saladin.[90]

Aftermath

Hassan-i Sabbah's objective was not realized, but nor was that of the Seljuks who intended to uproot the Nizaris who now formed a stable state of their own. The Nizari-Seljuk military confrontations became a stalemate by around 1120.[91]

The Nizari state weakened due to prolonged conflicts with several superior enemies. The indecisive Nizari policy against the Mongols also contributed to their fall after the Mongol invasion of Persia in 1219.[92] Though the Mongol massacre at Alamut was widely interpreted to be the end of Ismaili influence in the region, modern studies suggest that the Ismailis' political influence persisted. In 1275, a son of Rukn al-Din managed to recapture Alamut, though only for a few years. The Nizari imam, known in the sources as Khudawand Muhammad, recaptured the fort in the fourteenth century. According to Mar'ashi, the imam's descendants remained at Alamut until the late fifteenth century. Ismaili political activity in the region continued under the leadership of Sultan Muhammad ibn Jahangir and his son, until the latter's execution in 1597.[93] Deprived of political power, the Nizaris were scattered across many lands and live until the present day as religious minorities.[92]

The Nizari state enjoyed a degree of stability uncommon in other principalities of the Muslim World during the 11th century. These are attributed to their distinct methods of struggle, the genius of their early leaders, their strong solidarity, the sense of initiative of their local leaders, their appeal to outstanding individuals, as well as their strong sense of mission and total dedication to their ultimate ideal, which they maintained even after their initial failure against the Seljuks.[94] Conflicts continued between the Nizaris of Alamut and the people of Qazvin, the rulers of Tabaristan, and, after the decline of the Seljuks, the Khwarezmshahs. The Ismailis of Quhistan were engaged against the Ghurids, while those of Syria gradually became independent of Alamut.[3]

Nizari methods

Decentralized strongholds

The struggles of the Ismailis in Persia were characterized by distinctive patterns and methods. Modeled and named after the hijra (emigration) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Medina, the Nizaris established headquarters called dar al-hijra in Iraq, Bahrayn, Yemen and the Maghreb. These were strongholds serving as defensible places of refuge as well as local headquarters for regional operations. The da'is who controlled these strongholds operated independently but cooperated with one other. This coordinated, decentralized model of revolt proved to be effective since in the structure of the Seljuk Empire, especially after Malikshah, authority was locally distributed, with power divided between numerous emirs and commanders (see iqta'); therefore, there was no single target to be confronted by a strong army, even if the Ismailis could have mobilized such an army.[95]

.jpg.webp)

The Ismaili fortresses in Rudbar were able to withstand long sieges: in addition to the inaccessibility of the terrain, the fortifications were built on rocky heights and were equipped with large storehouses and elaborate water supply infrastructure.[3]

The Nizaris maintained cells in the cities and bases in remote areas. This strategy facilitated rapid expansion but also made them vulnerable.[96]

Assassination

The aforementioned structure of the Seljuk Empire, as well as the vastly superior Seljuk military, also suggested the Nizaris employ targeted assassination to achieve their military and political goals, which they effectively did to disrupt the Seljuk Empire.[97][71] They later owed their name, Assassin, to this technique, and all the important assassinations in the region were usually attributed to them.[98]

Although many medieval anti-Nizari legends were developed with respect to this technique, little historical information is known regarding the selection and training of the fida'is (plural fidā'iyān). All ordinary Ismailis in Persia, who referred to each other as "comrade" (rafīq, plural rafīqān) were supposedly ready to conduct any task for the Ismaili community. However, in the late Alamut period, the fida'is probably formed a special corps. They had a strong group sentiment and solidarity.[99]

The Nizaris viewed their assassinations, in particular those of the well-guarded, notorious targets which required a sacrificial assassination by a fida'i, as acts of heroism.[100] Rolls of honors containing their names and their victims were kept at Alamut and other fortresses.[101][10] They saw a humane justification in this method, as the assassination of a single prominent enemy served to save the lives of many other men on the battlefield. The missions were performed publicly as much as possible in order to intimidate other enemies.[102] The assassination of a town's prominent figure often triggered the Sunni population to massacre all (suspected) Ismailis in that town.[103]

Notes

- Those of the easternmost areas of the Ismaili world, notably Ghazna and the Oxus valley, remained outside of either the Nizari or Musta'li influence for a long time.

- An abortive assassination attempt in 1111 against Abu Harb Isa ibn Zayd, a wealthy Persian merchant in Aleppo, precipitated a public resentment of the Nizaris in the city.

- Among the executed were Abu Tahir himself, da'i Isma'il, and a brother of al-Hakim al-Munajjim.

- Including the commander of the Nizari armed forces in Aleppo, Husam al-Din ibn Dumlaj, who fled to al-Raqqa, and the commandant of the Balis fort, Ibrahim al-Ajami, who fled to Shayzar.

- Buri was instigated by the prefect of Damascus (ra'is al-shihna), Mufarrij ibn al-Hasan al-Sufi, and the city's military governor (ra'is al-shurta), Yusuf ibn Firuz.

- This practice became common among the Nizari leaders thereafter.

- According to Ibn al-Athir, Sultan Sanjar launched a punitive expedition against Alamut in which 10,000 Nizaris were killed, but this is probably an invention.

References

- Daftary 2007, p. 303-307

- Daftary 2007, p. 310-311

- B. Hourcade (2014)

- Daftary 2007, p. 310-311

- Daftary 2007, p. 313-314

- Daftary 2007, p. 314

- Daftary 2007, p. 314-316

- Daftary 2007, p. 318

- Daftary 2007, p. 318-319

- Lewis 2011, pp. 53—

- Daftary 2007, p. 317

- Daftary 2007, p. 316

- Iran in History Archived 2007-04-29 at the Wayback Machine by Bernard Lewis.

- Daftary 2007, p. 316

- Daftary 2007, p. 316

- Daftary 2007, p. 316

- Daftary 2007, p. 318

- Basan 2010, p. 318

- Daftary 2007, p. 319

- Cook 2012

- Daftary 2007, p. 319

- Daftary 2007, p. 319

- Daftary 2007, p. 320

- Daftary 2007, p. 320

- Daftary 2007, p. 320

- Peacock 2015, p. 75

- Daftary 2007, p. 324

- Daftary 2007, p. 325

- Daftary 2007, p. 326

- Comité international d'études pré-ottomanes et ottomanes Symposium 1998, p. 176

- Daftary 2007, p. 321-324

- Daftary 2007, p. 320-321

- Daftary 2007, p. 320-321

- Daftary 2020

- Daftary 2007, p. 321

- Daftary 2007, p. 329-330

- Daftary 2007, p. 329-330

- Daftary 2007, p. 329-330

- رازنهان 1392, p. 25

- Daftary 2007, p. 329-330

- Daftary 2007, p. 321

- Daftary 2007, p. 325

- Daftary 2007, p. 331-332

- Daftary 2007, p. 331-332

- Daftary 2007, p. 331-333

- Mirza 1997, pp. 8–12

- Daftary 2007, p. 333-334

- Daftary 2007, p. 334

- Daftary 2007, p. 334

- Daftary 2007, p. 334

- Particularly in the Jabal al-Summaq, the Jazr, and the Banu 'Ulaym's territories between Shayzar and Sarmin. See Daftary 2007, p. 335

- Daftary 2007, p. 349

- Gibb 1932, pp. 174–177, 179–180, 187–191

- Daftary 2007, p. 349

- Daftary 2007, p. 349

- Setton & Baldwin 1969, pp. 111–120

- Daftary 2007, p. 349

- Daftary 2007, p. 347-348

- Daftary 2007, p. 349

- Daftary 2007, p. 320-321

- Daftary 2007, p. 335

- Daftary 2007, p. 335-336

- Daftary 2007, p. 337

- رحمتی 2018

- Daftary 2007, p. 337

- Daftary 2007, p. 337

- Daftary 2007, p. 337

- Daftary 2001, p. 199

- Boyle 1968, pp. 118–119

- رازنهان 1392, p. 26

- Barash & Webel 2008, p. 53

- Daftary 2007, p. 338

- Daftary 2007, p. 342

- Daftary 2007, p. 338

- Daftary 2007, p. 345

- Daftary 2007, p. 345

- Daftary 2007, p. 345-346

- Daftary 2007, p. 345-346

- Cook 2012, pp. 97–117

- Durand-Guédy 2013, p. 153

- Wasserman 2001, p. 102

- Daftary 2007, p. 355-357

- Daftary 2007, p. 355-356

- Daftary 2007, p. 355-356

- Daftary 2007, p. 357

- Daftary 2007, p. 349-350, 352

- Daftary 2007, p. 332

- Daftary 2007, p. 349-350,352

- Daftary 2007, p. 349-350,352

- Daftary 2007, p. 355-356

- Daftary 2007, p. 301

- Daftary 2007, p. 303

- Virani 2003, pp. 351–370

- Daftary 2007, p. 355

- Daftary 2007, p. 326-327

- Brenner 2016, pp. 81–82

- Daftary 2007, p. 328

- Daftary 2007, p. 328

- Daftary 2007, p. 328-329

- Daftary 2007, p. 328

- Daftary 2007, p. 328

- Daftary 2007, p. 28

- Daftary 2007, p. 329

Sources

- Basan, Osman Aziz (24 June 2010). The Great Seljuqs: A History. ISBN 9781136953927.

- Barash, David P.; Webel, Charles P. (2008). Peace and Conflict Studies. SAGE. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4129-6120-2.

- Boyle, J. A., ed. (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 5 – The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. Cambridge University Press.

- Brenner, William J. (29 January 2016). Confounding Powers: Anarchy and International Society from the Assassins to Al Qaeda. Cambridge University Press. p. 81-82. ISBN 978-1-107-10945-2.

- Cook, David (1 January 2012). "Were the Ismāʿīlī Assassins the First Suicide Attackers? An Examination of Their Recorded Assassinations". The Lineaments of Islam: 97–117. doi:10.1163/9789004231948_007. ISBN 9789004231948.

- Daftary, Farhad (2001). Mediaeval Isma'ili History and Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521003100.

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines (2nd, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46578-6.

- Daftary, Farhad. "GERDKŪH – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Durand-Guédy, David, ed. (2013). Turko-Mongol Rulers, Cities and City Life. BRILL. p. 153. ISBN 978-90-04-25700-9.

- Gibb, N. A. R., ed. (1932). The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades. Extracted and translated from the Chronicle of ibn al-Qalānisi. Luzac & Company.

- B. Hourcade, “ALAMŪT,” Encyclopædia Iranica, I/8, pp. 797-801; an updated version is available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alamut-valley-alborz-northeast-of-qazvin- (accessed on 17 May 2014).

- Lewis, Bernard (2011). The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam. Orion. ISBN 978-0-297-86333-5.

- Mirza, Nasseh Ahmad (1997). Syrian Ismailism: The Ever Living Line of the Imamate, AD 1100-1260. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780700705054.

- Peacock, A. C. S. (2015). Great Seljuk Empire. Edinburgh University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7486-9807-3.

- Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W., eds. (1969) [1955]. A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Hundred Years (Second ed.). Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-04834-9.

- Comité international d'études pré-ottomanes et ottomanes Symposium (1998). Essays on Ottoman civilization. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute.

- Virani, Shafique (2003). "The Eagle Returns: Evidence of Continued Isma'ili Activity at Alamut and in the South Caspian Region following the Mongol Conquests". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 123 (2): 351–370. doi:10.2307/3217688. JSTOR 3217688.

- Wasserman, James (2001). The Templars and the Assassins: The Militia of Heaven. Simon and Schuster. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-59477-873-5.

- رازنهان, محمدحسن; خلیلی, مهدی (1392). "تحلیلی بر روابط سیاسی اسماعیلیان نزاری با خلافت عباسی". نشریه مطالعات تقریبی مذاهب اسلامی (فروغ وحدت) (in Persian) (32). ISSN 2252-0678.

- رحمتی, محسن (2018). خاندان برسقی و تحولات عصر سلجوقی (PDF) (in Persian).