Norman Cob

The Norman Cob or Cob Normand is a breed of light draught horse that originated in the region of Normandy in northern France. It is of medium size, with a range of heights and weights, due to selective breeding for a wide range of uses. Its conformation is similar to a robust Thoroughbred, and it more closely resembles a Thoroughbred cross than other French draught breeds. The breed is known for its lively, long-striding trot. Common colours include chestnut, bay and seal brown. There are three general subsets within the breed: horses used under saddle, those used in harness, and those destined for meat production. It is popular for recreational and competitive driving, representing France internationally in the latter, and is also used for several riding disciplines.

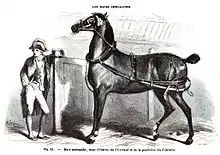

A stallion presented at the National Stud of Saint-Lô | |

| Other names | Cob Normand |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Normandy, France |

| Breed standards | |

The Normandy region of France is well known for its horse breeding, having also produced the Percheron and French Trotter. Small horses called bidets were the original horses in the area, and these, crossed with other types, eventually produced the Carrossier Normand, the immediate ancestor of the Norman Cob. Although known as one of the best carriage horse breeds available in the early 20th century, the Carrossier Normand became extinct after the advent of the automobile, having been used to develop the French Trotter, Anglo-Norman and Norman Cob. In its homeland, the Norman Cob was used widely for agriculture, even more so than the internationally known Percheron, and in 1950, the first studbook was created for the breed.

The advent of mechanisation threatened all French draught breeds, and while many draught breeders turned their production towards the meat market, Norman Cob breeders instead crossed their horses with Thoroughbreds to contribute to the fledgling Selle Français breed, now the national saddle horse of France. This allowed the Norman Cob to remain relatively the same through the decades, while other draught breeds were growing heavier and slower due to selection for meat. Between the 1970s and 1990s, the studbook went through several changes, and in the 1980s, genetic studies were performed that showed the breed suffered from inbreeding and genetic drift. Breed enthusiasts worked to develop new selection criteria for breeding stock, and population numbers are now relatively stable. Today, Norman Cobs are mainly found in the departments of Manche, Calvados and Orne.

Characteristics

The Norman Cob is a mid-sized horse,[1] standing between 160 and 165 centimetres (15.3 and 16.1 hands) and weighing 550 to 900 kilograms (1200 to 2000 lb).[2] The large variations in height and weight are explained by selection for a variety of uses within the breed.[3] The Norman Cob is elegant and closer in type to a Thoroughbred-cross than other French draught breeds.[4][5][6] Its conformation is similar to a robust Thoroughbred,[3] with a square overall profile and short back.[7] Selective breeding has been used to develop a lively trot,[8] with long strides.[9]

The head is well-proportioned[10] and similar to that of the Selle Français,[5] with wide nostrils, small ears and a straight or convex facial profile.[3][7][10] The neck is thick,[11] muscular and arched.[5][10] The mane is sometimes hogged.[3] The shoulders are broad and angled, the chest deep[5] and the withers pronounced.[3] The body is compact and stocky, with a short, strong back.[5][11][12] The hindquarters are powerful, although not so much as in heavy draught breeds,[11] and the croup muscular and sloping.[3][5] The legs are short, muscular and strong, with thick bone, but less massive than most draught breeds.[3] The feet are round, wide and solid.[11]

Colours accepted for registration include chestnut, bay and seal brown (the latter called black pangaré by the breed registry, although these horses are genetically brown, not black with pangaré markings).[2] Bays with white markings are the most popular.[5] The Norman Cob is a calm, willing horse with strong personality.[1][5][13] Its Thoroughbred ancestry gives them energy and athleticism,[9][13] and makes them mature faster than other draught breeds.[14] They show great endurance when ridden,[10] and are relatively hardy, accepting outdoor living and changes in climate.[9] Traditionally the Norman Cob had its tail docked, a practice that continued until January 1996, when the practice became illegal in France.[15]

There are three general subsets within the breed: horses used under saddle, those used in harness, and those destined for meat production.[3] Horses may be automatically registered if at least 87.5 per cent of their ancestors (seven out of eight) were registered Norman Cobs.[3][16] Purebred stallions may not be bred more than 70 times per year. Foals produced through artificial insemination and embryo transfer may be registered, but cloned horses may not.[3] In general, breeders look to produce horses with good gaits and an aptitude for driving, while keeping the conformation that makes the Norman Cob one of nine French draught breeds.[16]

History

The Norman Cob comes from the Normandy region of France, an area known for its horse breeding. Normandy is also the home of two other breeds, the Percheron and the French Trotter. Both of these breeds are better-known than the Norman Cob, although the latter is popular in its home region.[10] The name "cob" comes from the English and Welsh cobs that it resembles, with the addition of "Norman" to refer to the area in which it originated.[10][17] Although generally considered a member of the draught horse group, the Norman Cob is special among French draught breeds. It has been used almost exclusively for the production of sport horses, and has not been extensively used for the production of meat, unlike many other French draught breeds. This means that its conformation has remained relatively unchanged, as opposed to being bred for heavier weights for butchering.[1]

The original horses in Normandy and Brittany were small horses called bidets, introduced by the Celts. The Romans crossed these horses with larger mares, and beginning in the 10th century, these "Norman horses" were desired throughout Europe. During the 16th century, Norman horses were known to be heavy and strong, able to pull long distances, and used to pull artillery and diligences. Barb and Arabian blood was added during the reign of Louis XIV.[4][18][19] The Norman Cob is descended from this Norman horse, called the Carrossier Normand. It was also influenced by crossing with other breeds including the Mecklenburger,[20] the Gelderland horse and Danish horses.[19] By 1840, the Carrossier Normand had become more refined, due to crosses with imported British Norfolk Trotters,[19][21] as well as gaining better gaits, energy, elegance, and conformation.[20]

The Haras National de Saint-Lô (National Stud of Saint-Lô) was founded in 1806 by Napoleon. This stud and the Haras du Pin (Stud of Pin) became the main production centres for the Carrossier Normand. The Norman horse-Thoroughbred crossbreds produced at these studs were divided into two groups. The first were lighter cavalry horses, and the second were heavier horses, called "cobs",[10] used for draught work in the region.[22] At this time, there was no breed registry or studbook; instead, selective breeding was practised by the two studs, and farmers tested the capabilities of young horses to select breeding stock.[10]

Early 20th century

At the very beginning of the 20th century, the Carrossier Normand was considered the best carriage horses available.[4] The arrival of automobiles, and corresponding decline in demand for carriage horses, coincided with a split in the breed. A distinction was made between the lighter, faster horses in the breed, used for sport, and larger horses, used for agricultural work. The lighter horses eventually became the French Trotter (for driving) and Anglo-Norman (for riding and cavalry), while the heavier horses became the Norman Cob.[20] In 1912, when French horse populations were at their highest, there were 422 stallions at the Saint-Lô stud, mainly cobs and trotters.[10] When the original Carrossier Normand became extinct in the 1920s, breeding focused on the two remaining types,[9] with the Norman Cob continuing to be used for farming and the Anglo-Norman being used to create the Selle Français, the national French sport horse.[20]

In the regions of Saint-Lô and Cotentin, the Norman Cob was widespread in agricultural uses until 1950, and the population continued to increase in the first half of the 20th century, even through the occupation during World War II.[21] Even the Percheron, which was internationally recognised as the Norman draught horse, was not as popular in the homeland of the Norman Cob breed.[8] In 1945, Norman Cob stallions accounted for 40% of the conscripted horses,[21] and in 1950 a studbook was created for the breed.[23]

Like all French draught breeds, the Norman Cob was threatened by the advent of mechanisation in farming.[5] The only option left to many breeders was to redirect their production to the meat markets. However, the Norman Cob avoided this, through the efforts of Laurens St. Martin, the head of the Saint-Lô stud in 1944 and the developer of the Selle Français. He began crossing Thoroughbred stallions with Norman Cob mares to produce Selle Français horses, and the success of this program allowed a reorientation of the Cob breeding programs.[21] Although population numbers continued to decline until 1995, the physical characteristics of the breed remained much the same, not growing heavier and slower as many of the French draught breeds did due to breeding for the production of meat.[4][21] Even today, some Selle Français from Norman bloodlines are similar to the Norman Cob in appearance.[5]

1950 to 2000

The modern Norman Cob is slightly heavier than it was in the early 20th century,[10] due to lighter horses of the breed being absorbed into the Selle Français breed.[24] In 1976, the National Stud at Saint-Lô had 186 stallions, including 60 Norman Cobs.[18] In the same year, the breed registry was reorganised, and the Norman Cob placed in the draught horse category.[19] The reorganisation of the breed registry helped to reinvigorate Norman Cob breeding,[9] and to bring attention to the risk of extinction of the breed. In 1980, the Institut national de la recherche agronomique and Institut national agronomique performed demographic and genetic analysis of threatened breeds of horses within France. In 1982, researchers concluded that the Norman Cob has been inbred and suffered genetic drift from its original population. The increasing average age of Norman Cob breeders also made the situation of the breed precarious.[25]

Enthusiasts worked to reorient the breed towards driving and recreation pursuits,[5] and since 1982 have again reorganised the breed association. In 1992, a new studbook was created for the breed,[26] with new selection criteria designed to preserve the quality of the breed, particularly its gaits.[5] The latest editions of the breed registry and studbook are controlled by the Syndicat national des éleveurs et utilisateurs de chevaux Cob normand (National Union of Farmers and Users of Normandy Cob Horses), based in Tessy-sur-Vire.[27] The association works to preserve and promote the breed throughout France, focusing especially on Normandy, Vendée and Anjou.[28] In 1994, Normandy contained 2000 Percheron and Norman Cob horses, and annually bred around 600 foals of these two breeds. This included approximately half of the Norman Cobs bred in France.[29]

2000 to today

Today, Norman Cobs are mainly found in the departments of Manche, Calvados and Orne,[20][30] which form the area where the breed was originally developed. The region of Saint-Lô, which ranks first in the production of Norman Cobs, represents 35 per cent of new births.[18][30] The Norman Cob is also present around the Haras de la Vendée (Stud at Vendée), which represents 25 per cent of births, the Haras du Pin and in central Massif. In 2004, there were just over 600 French breeders of the Norman Cob, and in 2005, 914 Norman Cob mares were bred, with 65 stallions recorded as active in France. In recent years, the number of Norman Cobs has remained relatively stable.[30] In 2011, there were 319 Norman Cob births in France, and numbers of annual births between 1992 and 2010 ranged between 385 and 585.[31]

Members of the breed are shown annually at the Paris International Agricultural Show.[9] There are fairs held for the breed at Lessay and Gavray, in Manche.[9] The National Stud at Saint-Lô remains involved in the maintenance and development of the breed,[18] and organises the annual national competition for the breed.[9] The stud also organises events at which to present the breed to the public, including the Normandy Horse Show.[32][33] The Norman Cob is beginning to be exported to other countries, especially Belgium. In that country, some are bred pure, while others are crossed on the Ardennes to improve its gaits.[16] Approximately 15 horses are exported annually, travelling to Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and Italy for leisure, logging and agricultural uses.[34]

Uses

A multi-purpose breed,[5] the Norman Cob was formerly used wherever there was a need.[13] It was used in a variety of agricultural and other work by farmers,[5][6][13] and was used by the army for pulling artillery. The postal service used it to pull mail carriages,[20] which it was capable of doing at a fast trot over bad roads for long distances. Postal workers appreciated the breed for its willingness to remain calm, stationary and tethered for long periods of time.[12] Due to the modernisation of agriculture and transport, it is now used very little in these areas.[10]

The breed is popular for recreational and competitive driving,[6] to which it is well suited in temperament.[1][30] In 1997, the rules of driving events in France were modified to take into account the speed of execution of the course, which made lighter, faster horses more competitive. The Norman Cob and the lighter type of Boulonnais were particularly affected.[35] Its gaits,[30] calm temperament and willingness to master technical movements make it an excellent competitor,[7] and in 2011, more than a third of the horses represented in the French driving championships were Norman Cobs.[36] Many Norman Cobs represent France in driving events at international level.[9][37]

The Norman Cob is also used for riding, and may be used for most equestrian disciplines.[5] It is particularly well suited for vaulting.[38] Elderly and nervous riders often appreciate its calm temperament.[10] Lighter Cobs can be used for mounted hunts.[39] Crosses between the Norman Cob and Thoroughbred continue to be made to create saddle horses, generally with 25 to 50 per cent Cob blood.[5] Some Norman Cobs are bred for the meat market. The breed is sometimes preferred by butchers because of the lighter carcass weight and increased profitability over the Thoroughbred, while at the same time retaining meat similar in flavour and appearance to that of the Thoroughbred.[6]

Notes

- Bataille, 2008, p. 151

- "Standard du cheval Cob normand" (in French). Syndicat national des éleveurs et utilisateurs de chevaux Cob Normand. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Falcone, Patrick (December 28, 2010). "Règlement du stud-book du cob normand" (PDF) (in French). Les Haras Nationaux. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Dal'Secco, Emmanuelle (2006). Les chevaux de trait (in French). Editions Artemis. p. 23. ISBN 978-2-84416-459-9.

- Bataille, 2008, p. 153

- Hendricks, Bonnie (2007). International Encyclopedia of Horse Breeds. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-8061-3884-8.

- Deschamps and Cernetic, 2004, pp. 10–11

- Draper, Judith (2006). Le grand guide du cheval : les races, les aptitudes, les soins (in French). Éditions de Borée. p. 39. ISBN 978-2-84494-420-7.

- Collective, 2002, p. 115

- Edwards, 2006, p. 108

- Edwards, Elwyn Hartley (2005). L'œil nature – Chevaux (in French). Larousse. pp. 228–229. ISBN 978-2-03-560408-8.

- Edwards, 2006, p. 109

- Deschamps and Cernetic, 2004, pp. 7–8

- "La race Cob Normand" (in French). L'étrier picotin. Archived from the original on 2013-06-17. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Ouédraogo, Arouna P. & Le Neindre, Pierre (1999). L'homme et l'animal : Un débat de société (in French). Éditions Quae. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-2-7380-0858-9.

- "Présentation du cob normand" (in French). France Trait. Archived from the original on 2012-11-17. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Deschamps and Cernetic, 2004, p. 8

- Auzias, Dominique; Michelot, Caroline; Labourdette, Jean-Paul & Cohen, Delphine (2010). La France à cheval (in French). Petit Futé. p. 161. ISBN 978-2-7469-2782-7.

- Collective, 2002, p. 114

- Bataille, 2008, p. 152

- Danvy, Jean-Loup. "Histoire du cheval cob normand" (in French). Syndicat national des éleveurs et utilisateurs de chevaux Cob Normand. Archived from the original on 2013-06-20. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Cegarra, Marie (1999). L'animal inventé: ethnographie d'un bestiaire familier (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 89. ISBN 978-2-7384-8134-4.

- Mavré, 2004, p. 44

- Institut du cheval (1994). Maladies des chevaux: manuel pratique (in French). France Agricole Éditions. p. 11. ISBN 978-2-85557-010-5.

- Audiot, Annick (1995). Races d'hier pour l'élevage de demain: Espaces ruraux (in French). Éditions Quae. p. 87. ISBN 978-2-7380-0581-6.

- Deschamps and Cernetic, 2004, pp. 8–9

- Arné, Véronique & Zalkind, Jean-Marc (2007). L'élevage du cheval (in French). Educagri Éditions. p. 224. ISBN 978-2-84444-443-1.

- "Statuts du Syndicat Cob normand" (in French). Syndicat national des éleveurs et utilisateurs de chevaux Cob Normand. Archived from the original on 2013-06-20. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Pierre Carré (1997). Le ventre de la France: historicité et actualité agricoles des régions et départements français (in French). Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 96. ISBN 978-2-7384-5260-3.

- "Cob normand" (PDF) (in French). Les Haras Nationaux. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-28. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Syndicat national des éleveurs et utilisateurs de chevaux Cob Normand. "Le Cob Normand" (in French). Les Haras Nationaux. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- "Saint-Lô fait son show". Cheval Magazine (in French). 9 August 2010. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- Direction du développement des services (July 16, 2009). "L'attelage cob normand au NHS 2009" (in French). Les Haras Nationaux. Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Pilley-Mirande, Nathalie (October 2002). "Les traits français dans le monde". Cheval Magazine (in French) (371): 62–65.

- Mavré, 2004, p. 35

- "Le Cob Normand" (in French). Haras de la Vendée. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- "Des champions du trait s'entraînent en altitude". L'Indépendant (in French). August 22, 2011. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- Deutsch, Julie (2006). Débuter l'équitation. Les Équiguides (in French). Éditions Artemis. p. 123. ISBN 978-2-84416-340-0.

- Racic-Hamitouche, Françoise & Ribaud, Sophie (2007). Cheval et équitation. Éditions Artemis. p. 251. ISBN 978-2-84416-468-1.

References

- Bataille, Lætitia (2008). Races équines de France (in French). France Agricole Éditions. ISBN 978-2-85557-154-6.

- Collective (2002). Chevaux et poneys (in French). Éditions Artemis. ISBN 978-2-84416-338-7.

- Deschamps, Philippe & Cernetic, Isabelle (2004). Le Cob Normand (in French). Castor et Pollux. ISBN 978-2-912756-65-7.

- Edwards, Elwyn Hartley (2006). Les chevaux (in French). De Borée. ISBN 978-2-84494-449-8.

- Mavré, Marcel (2004). Attelages et attelées : un siècle d'utilisation du cheval de trait (in French). France Agricole Éditions. ISBN 978-2-85557-115-7.