Lambeth

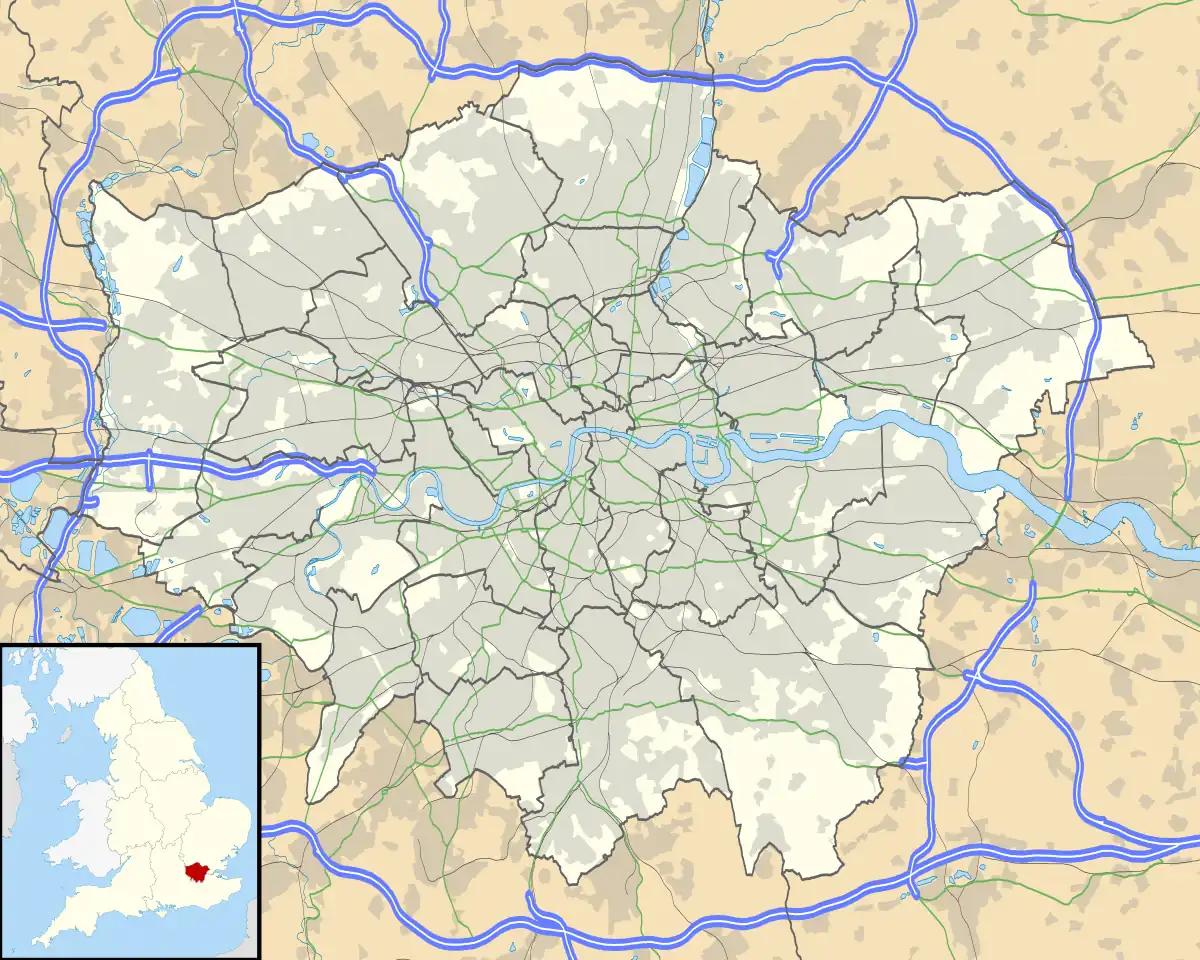

Lambeth (/ˈlæmbəθ/[1]) is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth was an ancient parish in the county of Surrey. It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011.[2] The area experienced some slight growth in the medieval period as part of the manor of Lambeth Palace. By the Victorian era the area had seen significant development as London expanded, with dense industrial, commercial and residential buildings located adjacent to one another. The changes brought by World War II altered much of the fabric of Lambeth. Subsequent development in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has seen an increase in the number of high-rise buildings. The area is home to the International Maritime Organization. Lambeth is home to one of the largest Portuguese-speaking communities in the UK, and Portuguese is the second most commonly spoken language in Lambeth after English.[3]

| Lambeth | |

|---|---|

The waterfront of Lambeth including the International Maritime Organization and the former HQ of the London Fire Brigade | |

Lambeth Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 9,675 (Bishop's ward 2011 census) |

| OS grid reference | TQ305785 |

| • Charing Cross | 1 mi (1.6 km) N |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | London |

| Postcode district | SE1 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

History

Medieval

The origins of the name of Lambeth come from its first record in 1062 as Lambehitha, meaning 'landing place for lambs', and in 1255 as Lambeth. In the Domesday Book, Lambeth is called "Lanchei", which is plausibly derived from Brittonic Lan meaning a river bank and Chei being Brittonic for a quay.[4] The name refers to a harbour where lambs were either shipped from or to. It is formed from the Old English 'lamb' and 'hythe'.[5] South Lambeth is recorded as Sutlamehethe in 1241 and North Lambeth is recorded in 1319 as North Lamhuth.[5]

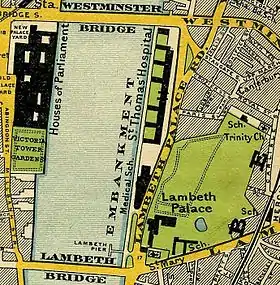

The manor of Lambeth is recorded as being under ownership of the Archbishop of Canterbury from at least 1190.[6] The Archbishops led the development of much of the manor, with Archbishop Hubert Walter creating the residence of Lambeth Palace in 1197.[7] Lambeth and the palace were the site of two important 13th-century international treaties; the Treaty of Lambeth 1217 and the Treaty of Lambeth 1212.[8] Edward, the Black Prince lived in Lambeth in the 14th century in an estate that incorporated the land not belonging to the Archbishops, which also included Kennington (the Black Prince road in Lambeth is named after him).[7] As such, much of the freehold land of Lambeth to this day remains under Royal ownership as part of the estate of the Duchy of Cornwall.[9] Lambeth was also the site of the principal medieval London residence of the Dukes of Norfolk, but by 1680 the large house had been sold and ended up as a pottery manufacturer, creating some of the first examples of English delftware in the country.[10] The road names, Norfolk Place and Norfolk Row reflect the history and legacy of the house today.[11]

River crossings

Lambeth Palace lies opposite the southern section of the Palace of Westminster on the Thames. The two were historically linked by a horse ferry across the river.[6] In fact, Lambeth could only be crossed by the left-bank by ferry or fords until 1750.[12] Until the mid-18th century the north of Lambeth was marshland, crossed by a number of roads raised against floods. This marshland was also known as Lambeth Marshe. It was drained in the 18th century but is remembered in the Lower Marsh street name. With the opening of Westminster Bridge in 1750, followed by the Blackfriars Bridge, Vauxhall Bridge and Lambeth Bridge itself, a number of major thoroughfares were developed through Lambeth, such as Westminster Bridge Road, Kennington Road and Camberwell New Road.[6] Until the 18th century Lambeth was sparsely populated[12] and still rural in nature, being outside the boundaries of central London, although it had experienced growth in the form of taverns and entertainment venues, such as theatres and Bear pits (being outside inner city regulations).[10] The subsequent growth in road and marine transport, along with the development of industry in the wake of the industrial revolution brought great change to the area.[10]

Early modern

The area grew with an ever-increasing population at this time, many of whom were considerably poor.[10] As a result, Lambeth opened a parish workhouse in 1726. In 1777 a parliamentary report recorded a parish workhouse in operation accommodating up to 270 inmates. On 18 December 1835 the Lambeth Poor Law Parish was formed, comprising the parish of St Mary, Lambeth, "including the district attached to the new churches of St John, Waterloo, Kennington, Brixton, Norwood". Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of twenty Guardians.[13] Following in the tradition of earlier delftware manufacturers, the Royal Doulton Pottery company had their principal manufacturing site in Lambeth for several centuries.[14] The Lambeth factory closed in 1956 and production was transferred to Staffordshire. However the Doulton offices, located on Black Prince Road still remain as they are a listed building, which includes the original decorative tiling.[14]

Between 1801 and 1831 the population of Lambeth trebled and in ten years alone between 1831 and 1841 it increased from 87,856 in to 105,883.[11] The railway first came to Lambeth in the 1840s, as construction began which extended the London and South Western Railway from its original station at Nine Elms to the new terminus at London Waterloo via the newly constructed Nine Elms to Waterloo Viaduct. With the massive urban development of London in the 19th century and with the opening of the large Waterloo railway station in 1848 the locality around the station and Lower Marsh became known as Waterloo, becoming an area distinct from Lambeth itself.[5]

The Lambeth Ragged school was built in 1851 to help educate the children of destitute facilities, although the widening of the London and South Western Railway in 1904 saw the building reduced in size.[10] Part of the school building still exists today and is occupied by the Beaconsfield Gallery.[10] The Beaufoy Institute was also built in 1907 to provide technical education for the poor of the area, although this stopped being an educational institution at the end of the 20th century.[10]

Modern

Lambeth Walk and Lambeth High Street were the two principal commercial streets of Lambeth, but today are predominantly residential in nature. Lambeth Walk was site of a market for many years, which by 1938 had 159 shops, including 11 butchers.[15] The street and surrounding roads, like most of Lambeth were extensively damaged in the Second World War.[15] This included the complete destruction of the Victorian Swimming Baths (themselves built in 1897) in 1945, when a V2 Rocket hit the street resulting in the deaths of 37 people.[16]

In 1948 when the first wave of immigrants of Afro-Caribbean descent arrived from Jamaica on the Windrush cruise ship, they were housed in several areas within Brixton, especially Clapham.[17] The Royal Pharmaceutical Society's headquarters were located in Lambeth High Street from 1976 until 2015.[18]

Today, the center of government in Brixton has a strong Afro-Caribbean community. Other significant minorities include Africans, South Asians, and Chinese; they make up one third of Lambeth's population.[12] The borough is a very densely populated area within London with a large young population. One third of its working age population are considered living in poverty. Lambeth ranks 8th out of 22 of the most deprived boroughs in London.[19]

Local governance

The current district of Lambeth was part of the large ancient parish of Lambeth St Mary in the Brixton hundred of Surrey.[20] It was an elongated north–south parish with a two-mile (three-kilometre) River Thames frontage to the west. In the north it lay opposite the cities of London and Westminster and extended southwards to cover the contemporary districts of Brixton, West Dulwich and West Norwood, almost reaching Crystal Palace. Lambeth became part of the Metropolitan Police District in 1829. It continued as a single parish for Poor Law purposes after the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 and a single parish governed by a vestry after the introduction of the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1855.[20] In 1889 it became part of the County of London and the parish and vestry were reformed in 1900 to become the Metropolitan Borough of Lambeth, governed by Lambeth Borough Council. In the reform of local government in 1965, the Streatham and Clapham areas that had formed part of the Metropolitan Borough of Wandsworth were combined with Lambeth to form the responsible area of local government under the London Borough of Lambeth. The current mayor is Annie Gallop as of May 2021.[21]

Local politics

The council is run by a leader and cabinet. All cabinet members are from the Labour Party.

Since the 2022 Lambeth London Borough Council election, there are two Opposition groups. The Majority Opposition Group being the Liberal Democrats (UK) with their Leader, Councillor Donna Harris and Deputy Leader, Councillor Matthew Bryant. The Minority Opposition Group is led by the Green Party of England and Wales with Co-Leaders, Councillor Scott Ainslie and Councillor Nicole Griffiths.[22]

The chief executive is Bayo Dosunmu.[23]

The current Mayor is Councillor Sarbaz Barznji.[24]

In the 2016 EU referendum, Lambeth issued the highest "Remain" vote in the United Kingdom (besides Gibraltar) with almost 79% of residents advocating the United Kingdom staying in the European Union.

At the 2015 general election, all three Labour candidates were elected Kate Hoey for Vauxhall, Chuka Umunna for Streatham & Helen Hayes for Dulwich and West Norwood. The Conservative Party finished the runners up in all three seats.

At the snap 2017 general election, Hoey, Umunna and Hayes were re-elected with increased majorities. The Liberal Democrat candidate George Turner finished the runner up in Vauxhall achieving a 5% swing in his favour. The Conservative candidates Rachel Wolf and Kim Caddy finished the runner up in Dulwich & West Norwood and Streatham respectively.

At the 2018 local elections, Labour remained in control of the council with 57 of the 63 seats, (down 2 seats from 2014). The Greens gained 4 seats and achieved a total 5 seats. The Conservatives were reduced down to a single seat, and the Liberal Democrats failed to gain any seats, but did make some inroads into Wards in Northern Vauxhall and Southern Streatham.

In the 2019 EU elections, the Liberal Democrats won Lambeth with 33% of the vote, Labour were second with 21%, The Greens third with 19% and Change UK and The Brexit Party joint fourth on 8%.

In June 2019, Umunna defected to the Liberal Democrats.

Hoey stood down at the 2019 General Election and was replaced with Labour MP Florence Eshalomi, who was the sitting London Assembly Member for Lambeth and Southwark. Ummuna stood down as an MP and was replaced with Bell Ribeiro-Addy where the Labour majority was cut by almost 10,000 by the 2nd placed Lib Dems. Hayes stood for re-election with the Green Party's Jonathan Bartley finishing in second place, for the first time.

In 2023, the Lambeth Council endorsed the international Plant Based Treaty.[25]

Buildings and churches

.jpg.webp)

The church of St Mary-at-Lambeth is the oldest above ground structure in Lambeth, the oldest structure of any kind being the crypt of Lambeth Palace itself.[26] The church has pre-Norman origins, being recorded as early as 1062 as a church built by Goda, sister of Edward the Confessor. It was rebuilt in flint and stone between the years 1374 and 1377. The tower is the only original part still to survive, as much of the church was reconstructed by 1852. The church was de-consecrated in 1972 and since 1977 it has been the home of the Garden Museum.[26]

Lambeth Palace is the home of the Archbishop of Canterbury and has been occupied as a residence by the Archbishops since the early 13th century.[27] The oldest parts of the palace are Langton's Chapel and its crypt, both of which date back to the 13th century. Although they suffered greatly from damage in the Second World War, they have seen been extensively repaired and restored.[27] Morton's Tower, the main entrance to the palace, was built in 1490.[27] The Great Hall, rebuilt over different centuries but primarily following damage during the English Civil War, contains the vast collections of the Lambeth Palace Library.[27] Later additions to the palace including the Blore Building, a newer private residence for the Archbishop, which was completed in 1833.[27]

.jpg.webp)

The Albert Embankment, finished in 1869 and created by the engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette under the Metropolitan Board of Works, forms the boundary of Lambeth. The embankment includes land reclaimed from the river and various small timber and boatbuilding yards, and was intended to protect low-lying areas of Lambeth from flooding while also providing a new highway to bypass local congested streets. Unlike the Thames Embankment on the opposite side of the river, the Albert Embankment does not incorporate major interceptor sewers. This allowed the southern section of the embankment (upstream from Lambeth Bridge) to include a pair of tunnels leading to a small slipway, named White Hart Draw Dock, whose origins can be traced back to the 14th century.[28] Centuries later, Royal Doulton's pottery works used the docks to load clay and finished goods for transport to and from the Port of London. The refurbishment of White Hart Dock was carried out as part of a local art project in 2009, which included the addition of wooden sculptures and benches to the 1868 dock boundary wall.[14]

Located on the Albert Embankment is the purpose-built headquarters of the International Maritime Organization (IMO).[29] The IMO is a specialised agency of the United Nations responsible for regulating shipping.[30] The building was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 17 May 1983.[29] The architects of the building were Douglass Marriott, Worby & Robinson.[31] The front of the building is dominated by a seven-metre high, ten-tonne bronze sculpture of the bow of a ship, with a lone seafarer maintaining a look-out from Lambeth to the Thames.[31]

From 1937 until 2007 the headquarters of the London Fire Brigade were in Lambeth, on Albert Embankment.[32] The headquarters building, constructed in an art deco style, was designed by architects of the London City Council and opened in 1937.[32] Occupying a prominent position on the Thames it is, however, still an operating fire station, although future plans have been submitted which may see redevelopment of the listed building.[33] A planning decision is expected by July 2023.[34]

The Lambeth Mission is a church of the united Methodist Anglican denomination, located on Lambeth Road.[35] The original church was founded in 1739 but was entirely destroyed by a bomb in the Second World War. A new church for the mission was constructed in 1950 and continues to function as an active church today.[35]

The Beaconsfield gallery is a public contemporary art gallery in Lambeth, which was established in 1995 and specialises in temporary exhibitions and art classes.[36] Morley College is an adult education college, founded in the 1880s, that occupies sites on either side of the boundary between the London boroughs of Southwark and Lambeth.[37]

Literary Lambeth

In William Blake's epic Milton: A Poem in Two Books, the poet John Milton leaves Heaven and travels to Lambeth, in the form of a falling comet, and enters Blake's foot. This allows Blake to treat the ordinary world as perceived by the five senses as a sandal formed of "precious stones and gold" that he can now wear. Blake ties the sandal and, guided by Los, walks with it into the City of Art, inspired by the spirit of poetic creativity. The poem was written between 1804 and 1810.

Liza of Lambeth, the first novel by W. Somerset Maugham, is about the life and loves of a young factory worker living in Lambeth near Westminster Bridge Road.[38]

Thyrza, a novel by George Gissing first published in 1887, is set in late Victorian Lambeth, particularly Newport Street, Lambeth Walk and Walnut Tree Walk. The novel was intended by Gissing to "contain the very spirit of London working-class life". The story tells of Walter Egremont, an Oxford-trained idealist who gives lectures on literature to workers, some of them from his father's Lambeth factory.

Leisure and recreation

Lambeth has several areas of public parks and gardens. This includes Old Paradise Gardens, which is a park occupying a former burial ground on Lambeth High Street and Old Paradise Street. A watch-house for holding the 'drunk and disorderly' existed on the site, from 1825 until 1930 and is today marked by a memorial stone.[39] Lambeth Walk Open Space is a small public park to the east of Lambeth on Fitzalan Walk and includes several open spaces and play areas.[40] Pedlars' Park is another small public park in Lambeth, which was created in 1968 on the site of the former St. Saviour's Salamanca Street School.[41] Archbishop's Park is open to the public and borders the edge of Lambeth Palace and the neighbouring area of Waterloo and the hospital of St Thomas.

Transport

The nearest London Underground stations are Waterloo, Southwark and Lambeth North. London Waterloo is also a National Rail station as is Waterloo East which is located in-between both Waterloo and Southwark stations. Vauxhall station is also nearby in Vauxhall, situated more towards the South Lambeth area near Kennington as is Oval station nearby. The South West Main Line runs through Lambeth on the Nine Elms to Waterloo Viaduct.

The principal road through the area is Lambeth Road (the A3203). Lambeth Walk adjoins Lambeth Road. The current Lambeth Bridge opened on 19 July 1932. It replaced an earlier suspension bridge which itself was built between 1862 and 1928, but was eventually closed and demolished following the 1928 Thames flood.[42]

Notable people

See also

References

- "Lambeth". Collins Dictionary.

- Services, Good Stuff IT. "Lambeth – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Maria-Joao, Melo Nogueira; David, Porteous; Sandra, Guerreiro (July 2015). "The Portuguese-speaking community in Lambeth: a scoping study". eprints.mdx.ac.uk. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Wheatley, Henry Benjamin; Cunningham, Peter (2011) [First published in 1891]. London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions. Cambridge University Press. p. 355. ISBN 9781108028073.

- Mills, D. (2000). Oxford Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford.

- "London Borough of Lambeth". Ideal Homes: A History of South-East London Suburbs. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Lambeth". Vauxhall History Online Archive. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Cannon, John. "Treaty of Lambeth" A Dictionary of British History. Oxford University Press, 2009

- "Royal Southwark and Lambeth". Vauxhall History Online Archive. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "Lambeth Pharmacy Walk" (PDF). Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Lambeth: The parish". British History. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Lambeth | Description, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- "Lambeth (Parish of St Mary), Surrey, London". workhouses.org. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Memorial – White Hart Dock". London Remembers. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Streets of London: Lambeth Walk". BBC News. 24 May 2004. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "Lambeth Baths". Vauxhall History Online Archives. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Diakite, Parker (27 February 2019). "The Brixton Pound: London's Historically Black Neighborhood Creates Own Currency". Travel Noire. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- "Pharmacy History and Lambeth". Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "State of the Borough 2016" (PDF). lambeth.gov.uk. 2016. p. 5.

- Youngs, Frederic (1979). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England. Vol. I: Southern England. London: Royal Historical Society. ISBN 0-901050-67-9.

- "CLLR Annie Gallop elected Mayor of Lambeth with the Ebony Horse Club at Loughborough Junction nominated as her chosen charity". 22 April 2021.

- "Opposition group leader | Lambeth Council". www.lambeth.gov.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- "How Lambeth Council is organised | Lambeth Council". www.lambeth.gov.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- "About the Mayor | Lambeth Council". www.lambeth.gov.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- "Council goes plant-based". www.hortweek.com. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- "St Mary – A history". The Garden Museum. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "The History of Lambeth Palace". The Archbishop of Canterbury. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "White Hart Dock". Plaques of London. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "IMO History: 30 years" (PDF). International Maritime Organization. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Introduction to IMO". International Maritime Organization. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "IMO Building History". Manchester History. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Fire Brigade HQ History". Manchester History. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Developer appointed for Albert Embankment Site". London Fire Brigade. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "8 Albert Embankment development". London Fire Brigade. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "Lambeth Mission & St Mary's". North Lambeth Parish. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Main Site". Beaconsfield Gallery. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "About". Morley College. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Liza of Lambeth". Vauxhall History Online Archive. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Lambeth Parish Watch House". Vauxhall History Online Archive. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "Lambeth Walk Open Space". Open Play. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Pedlars' Park". London Park Life. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Lambeth Bridge and its predeceasor". British History. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

Further reading

- Daniel Lysons (1792), "Lambeth", Environs of London, vol. 1: County of Surrey, London: T. Cadell

- John Timbs (1867), "Lambeth", Curiosities of London (2nd ed.), London: J.C. Hotten, OCLC 12878129

- Findlay Muirhead, ed. (1922), "Lambeth", London and its Environs (2nd ed.), London: Macmillan & Co., OCLC 365061

External links

- london-se1.co.uk – local news website

- Lambeth, In Their Shoes – Lambeth history resource

- Digital Public Library of America. Works related to Lambeth, various dates