Orion-class battleship

The Orion-class battleships were a group of four dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Navy (RN) in the early 1910s. The first 13.5-inch-gunned (343 mm) battleships built for the RN, they were much larger than the preceding British dreadnoughts and were sometimes termed "super-dreadnoughts". The sister ships spent most of their careers assigned to the 2nd Battle Squadron of the Home and Grand Fleets, sometimes serving as flagships. Aside from participating in the failed attempt to intercept the German ships that had bombarded Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in late 1914, the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 and the inconclusive action of 19 August, their service during World War I generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea.

Thunderer at anchor, shortly after completion in 1912 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Orion-class battleship |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Colossus class |

| Succeeded by | King George V class |

| Built | 1909–1912 |

| In commission | 1912–1922 |

| Completed | 4 |

| Scrapped | 4 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 21,922 long tons (22,274 t) (normal) |

| Length | 581 ft (177.1 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 88 ft 6 in (27.0 m) |

| Draught | 27 ft 6 in (8.4 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,730 nmi (12,460 km; 7,740 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 738–1,107 (1917) |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

The Orions were deemed obsolete by the end of the war in 1918 and were reduced to reserve the following year. Orion and Conqueror were sold for scrap in 1922 while Monarch was hulked for use as a stationary training ship. In late 1923, she was converted into a target ship and was sunk in early 1925. Thunderer served the longest, acting as a training ship from 1921 until she, too, was sold for scrap in late 1926. While being towed to the scrapyard, the ship ran aground; Thunderer was refloated and subsequently broken up.

Background and design

The initial 1909–1910 Naval Programme included two dreadnoughts and a battlecruiser, but was later increased to six dreadnoughts and two battlecruisers as a result of public pressure on the government due to the Anglo-German naval arms race. The original pair of battleships became the Colossus class and were improved versions of the preceding battleship, HMS Neptune. A third dreadnought was added to the programme around April 1909 that was to be armed with more powerful 13.5-inch (343 mm) weapons than the 12-inch (305 mm) guns used in the earlier dreadnoughts. Three more ships of this class, as well as another battlecruiser, were part of the contingency programme authorized in August.[1]

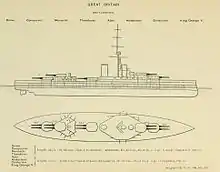

Unlike all of the previous dreadnoughts, which had been incremental improvements of the original HMS Dreadnought design of 1906, constrained by cost and size limits, the Orion class were almost a "clean-slate" design driven by the need to accommodate the larger guns and additional armour. The guns were positioned all on the centreline of the hull in superfiring gun turrets, an arrangement first used in HMS Neptune for the aft main turrets. The idea had been pioneered by the United States Navy in their South Carolina class, but the RN was slow to adopt the concept, concerned about the effects of muzzle blast on the gunlayers in the open sighting hoods in the roofs of the lower turrets.[2]

One of the few things retained from earlier ships was the position of the tripod foremast with its spotting top behind the forward funnel to allow the vertical leg to be used to support the boat-handling derrick. This all but guaranteed that the hot funnel gases could render the spotting top uninhabitable at times, but the Board of Admiralty insisted on it for all the ships of the 1909–1910 Programme.[3] David K. Brown, naval architect and historian, commented on the whole fiasco: "It is amazing that it took so long to attain a satisfactory arrangement, which was caused by the Director of Naval Ordnance (DNO)'s insistence on sighting hoods in the roofs of turrets and Jellicoe's obsession with boat-handling arrangements. These unsatisfactory layouts reduced firepower, prejudiced torpedo protection and probably added to cost. As DNO and then as Controller, Jellicoe must accept much of the blame for the unsatisfactory layout of the earlier ships."[4]

Description

The Orion-class ships had an overall length of 581 feet (177.1 m), a beam of 88 feet 6 inches (27.0 m), a normal draught of and 27 feet 6 inches (8.4 m) a deep draught of 31 feet 3 inches (9.5 m). They displaced 21,922 long tons (22,274 t) at normal load and 25,596 long tons (26,007 t) at deep load. Their crew numbered 738 officers and ratings upon completion and 1,107 in 1917.[5]

The ships retained the three engine-room layout of the Colossus-class design. They were powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines. The outer propeller shafts were coupled to the high-pressure turbines in the outer engine rooms and these exhausted into low-pressure turbines in the centre engine room which drove the inner shafts. The turbines used steam provided by 18 water-tube boilers. They were rated at 27,000 shaft horsepower (20,000 kW) and were intended to give the battleships a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). During their sea trials, the Orions exceeded their designed speed and horsepower. They carried a maximum of 3,300 long tons (3,353 t) of coal and an additional 800 long tons (813 t) of fuel oil that was sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. This gave them a range of 6,730 nautical miles (12,460 km; 7,740 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[6]

Armament

These ships were the first to carry the new breech-loading (BL) 13.5-inch Mark V gun. This gun was developed as the RN believed that the preceding 12-inch Mark XI gun could not be further developed and that a new gun of an increased bore was needed to deal with the longer ranges at which combat was expected to occur and the need for greater penetration and destructive effect. The Mark V gun had a muzzle velocity about 300 feet per second (91 m/s) lower than the Mark XI gun, which greatly reduced the wear in the barrel. Despite the reduction in velocity, the gun's range was about 2,500 yards (2,286 m) greater because the much heavier 13.5-inch shell retained its velocity longer than the lighter and smaller 12-inch shell.[7]

The Orion class was equipped with ten 45-calibre Mark V guns in five hydraulically powered, centreline, twin-gun turrets, designated 'A', 'B', 'Q', 'X' and 'Y' from front to rear.[5] The guns had a maximum elevation of +20° which gave them a range of 23,820 yards (21,781 m). Their gunsights, however, were limited to +15° until super-elevating prisms were installed by 1916 to allow full elevation.[8] They fired 1,250-pound (567 kg) projectiles, some 400 pounds (180 kg) more than those of the 12-inch Mark XI, at a muzzle velocity of 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s) at a rate of two rounds per minute.[9] The ships carried 80–100 shells per gun.[5]

Their secondary armament consisted of sixteen 50-calibre BL four-inch (102 mm) Mark VII guns. Four of these guns were in exposed mounts on the shelter deck and the remaining guns were enclosed in unshielded single mounts in the superstructure.[10] The guns had a maximum elevation of +15° which gave them a range of 11,400 yd (10,424 m). They fired 31-pound (14.1 kg) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,821 ft/s (860 m/s).[11] They were provided with 150 rounds per gun. Four 3-pounder (1.9 in (47 mm)) saluting guns were also carried. The ships were equipped with three 21-inch submerged torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and another in the stern, for which 20 torpedoes were provided.[5]

Fire control

The control positions for the main armament were located in the spotting tops at the head of the fore and mainmasts. Data from a nine-foot (2.7 m) Barr and Stroud coincidence rangefinder, located at each control position, was input into a Dumaresq mechanical computer and electrically transmitted to Vickers range clocks located in the transmitting station located beneath each position on the main deck, where it was converted into range and deflection data for use by the guns. The target's data was also graphically recorded on a plotting table to assist the gunnery officer in predicting the movement of the target. The turrets, transmitting stations, and control positions could be connected in almost any combination.[12] As a backup, two turrets in each ship could take over if necessary.[13]

Thunderer was the second British dreadnought to be built with a gunnery director, albeit a prototype.[14] This was mounted on the foremast, underneath the spotting top and electrically provided data to the turrets via pointers, which the turret crew were to follow. The director layer fired the guns simultaneously which aided in spotting the shell splashes and minimised the effects of the roll on the dispersion of the shells.[15] While the exact dates of installation are uncertain, all four ships were equipped with a director by December 1915.[16]

Additional nine-foot rangefinders, protected by armoured hoods, were added for each gun turret in late 1914.[17] Furthermore, the ships were fitted with Mark II or III Dreyer Fire-control Tables, in early 1914, in each transmission station. It combined the functions of the Dumaresq and the range clock.[18]

Armour

The Orion class had a waterline belt of Krupp cemented armour that was 12 inches thick between the fore and rear barbettes that was reduced to 2.5–6 inches (64–152 mm) outside the central armoured citadel, but did not reach the bow or stern. The belt covered the side of the hull from the middle deck to 3 feet 4 inches (1.0 m) below where the waterline and thinned to 8 inches (203 mm) at its bottom edge. Above this was a strake of 8-inch armour. The forward oblique 6-inch (152 mm) bulkheads connected the waterline and upper armour belts to the 'A' barbette. Similarly the aft bulkhead connected the armour belts to 'Y' barbette, although it was 8 inches thick. The exposed faces of the barbettes were protected by armour 10 inches (254 mm) thick above the main deck that thinned to 3–7 inches (76–178 mm) below it. The gun turrets had 11-inch (279 mm) faces and 8-inch sides with 3-inch roofs.[19]

The four armoured decks ranged in thickness from 1 to 4 inches (25 to 102 mm) with the greater thicknesses outside the central armoured citadel. The front and sides of the conning tower were protected by 11-inch plates, although the roof was 3 inches thick. The spotting tower behind and above the conning tower had 6-inch sides and the torpedo-control tower aft had 3-inch sides and a 2-inch roof. Like the Colossus-class ships, the Orions eliminated the anti-torpedo bulkheads that protected the engine and boiler rooms, reverting to the scheme in the older dreadnoughts that placed them only outboard of the magazines with thicknesses ranging from 1 to 1.75 inches (25 to 44 mm). The boiler uptakes were protected by 1–1.5-inch (25–38 mm) armour plates.[20]

Modifications

Conqueror received a small rangefinder on the roof of 'B' turret in 1914; the other ships may also have had one installed. That same year the shelter-deck guns of the sisters were enclosed in casemates. By October 1914, a pair of QF 3-inch (76 mm) anti-aircraft (AA) guns were installed aboard each ship. Additional deck armour was added after the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. Around the same time, three or four 4-inch guns were removed from the aft superstructure. By April 1917, the ships had exchanged a 4-inch AA gun for one of the 3-inch guns. One or two flying-off platforms were fitted aboard each ship during 1917–1918; these were mounted on turret roofs and extended onto the gun barrels. Orion had them on 'B' and 'Q' turrets, Conqueror and Thunderer on 'B' and 'X' turrets and Monarch had one on 'B'. A high-angle rangefinder was fitted in the forward superstructure by 1921. Thunderer had her secondary armament reduced to eight guns during her February–May 1921 conversion into a training ship.[21]

Ships

| Ship | Builder[22] | Laid down[22] | Launched[22] | Commissioned[23] | Cost (including armament) according to | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burt[5] | Parkes[10] | |||||

| Orion | HM Dockyard, Portsmouth | 29 November 1909 | 20 August 1910 | 2 January 1912 | £1,855,917 | £1,918,773 |

| Monarch |

Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick | 1 April 1910 | 30 March 1911 | 27 April 1912 | £1,888,736 | £1,886,912 |

| Conqueror | William Beardmore, Dalmuir | 5 April 1910 | 1 May 1911 | 1 December 1912 | £1,891,164 | £1,860,648 |

| Thunderer | Thames Ironworks, London | 13 April 1910 | 1 February 1911 | 15 June 1912 | £1,892,823 | £1,885,145 |

Careers

Upon commissioning, all four sisters were assigned to the 2nd Division of the Home Fleet or, as it was redesignated on 1 May 1912, the 2nd Battle Squadron (BS). Orion became the flagship of the division's second-in-command, retaining that position until March 1919. Monarch, Thunderer and Orion[Note 1] participated in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead. They then participated in training manoeuvres with Vice-Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg commanding the "Blue Fleet" aboard Thunderer. The three sisters were present with the 2nd BS to receive the President of France, Raymond Poincaré, at Spithead on 24 June 1913. During the annual manoeuvres in August, Thunderer was the flagship of Vice-Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the "Red Fleet".[23]

Between 17 and 20 July 1914, the Orions took part in a test mobilisation and fleet review as part of the British response to the July Crisis. Afterwards, they were ordered to proceed with the rest of the Home Fleet to Scapa Flow[23] to safeguard the fleet from a possible surprise attack by the Imperial German Navy. After the British declaration of war on Germany on 4 August, the Home Fleet was reorganised as the Grand Fleet, and placed under the command of Admiral Jellicoe.[24] According to pre-war doctrine, the role of the Grand Fleet was to fight a decisive battle against the German High Seas Fleet. This grand battle was slow to happen, however, because of the Germans' reluctance to commit their battleships against the superior British force. As a result, the Grand Fleet spent its time training in the North Sea, punctuated by the occasional mission to intercept a German raid or major fleet sortie.[25]

Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

Room 40, the Signals intelligence organisation at the Admiralty, had decrypted German radio traffic containing plans for a German attack on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in mid-December using the four battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group (Konteradmiral [Rear-Admiral] Franz von Hipper). The radio messages did not mention that the High Seas Fleet with fourteen dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnoughts would reinforce Hipper. The ships of both sides departed their bases on 15 December, with the British intending to ambush the German ships on their return voyage. The British mustered the six dreadnoughts of the 2nd BS (Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender), including Orion and her sister ships, Monarch and Conqueror and the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron (Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty).[26]

The screening forces of each side blundered into each other during the early morning darkness and heavy weather of 16 December. The Germans got the better of the initial exchange of fire, severely damaging several British destroyers but Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, commander of the High Seas Fleet, ordered his ships to turn away, concerned about the possibility of a massed attack by British destroyers in the dawn. Incompetent communications and mistakes by the British allowed Hipper to avoid an engagement with the battlecruisers.[27] On 27 December, Conqueror accidentally rammed Monarch as the Grand Fleet was returning to Scapa Flow in heavy weather and poor visibility. The latter ship required less than a month of repairs but Conqueror was not ready for service until March 1915.[28]

Battle of Jutland

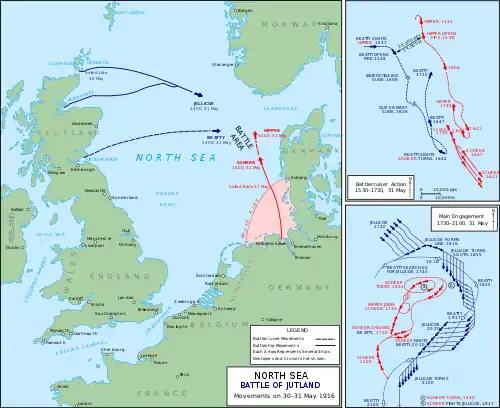

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May 1916 in support of Hipper's battlecruisers which were to act as bait. Room 40 had again intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation, so the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[29]

Once Jellicoe's ships had rendezvoused with the 2nd BS, coming from Cromarty, Scotland, on the morning of 31 May, he organised the main body of the Grand Fleet in parallel columns of divisions of four dreadnoughts each. The two divisions of the 2nd BS were on his left (east), the 4th BS was in the centre and the 1st BS on the right. When Jellicoe ordered the Grand Fleet to deploy to the left and form line astern in anticipation of encountering the High Seas Fleet, this naturally placed the 2nd BS at the head of the line of battle.[30] In the early stage of the battle, Conqueror and Thunderer fired at the crippled light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden with unknown results. The two ships also engaged German dreadnoughts, but failed to make any hits. Monarch and Orion, in contrast, did not fire at Wiesbaden, but shot at and hit several German dreadnoughts. Between them, the pair hit the battleships SMS König and SMS Markgraf once each, lightly damaging them, and the battlecruiser SMS Lützow five times, significantly damaging her. The sisters were not heavily engaged during the battle, with none of them firing more than 57 rounds from their main guns.[31]

Subsequent activity

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August 1916 to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boats during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or there was a strong possibility it could be forced into an engagement under suitable conditions.[32] Along with the rest of the Grand Fleet, they sortied on the afternoon of 23 April 1918 after radio transmissions revealed that the High Seas Fleet was at sea after a failed attempt to intercept the regular British convoy to Norway. The Germans were too far ahead of the British to be caught, and no shots were fired.[33] The sisters were present at Rosyth, Scotland, when the German fleet surrendered there on 21 November.[34]

They remained part of the 2nd BS through February 1919,[35] but had been transferred to the 3rd BS of the Home Fleet by May, Orion becoming the squadron flagship.[36] By the end of 1919, the 3rd BS had been disbanded and the sisters had been transferred to the Reserve Fleet at Portland, although Monarch was transferred to Portsmouth in early 1920.[37] Monarch and Thunderer were temporarily recommissioned during the summer of 1920 to ferry troops to the Mediterranean and back.[28] Orion joined Monarch at Portsmouth later in the year and became the flagship of the Reserve Fleet.[38] Conqueror followed Orion to Portsmouth and relieved her as flagship in mid-1921 and the latter ship was again temporarily recommissioned to transport troops. Thunderer was converted into a training ship for naval cadets in 1921 and Orion became a gunnery training ship after being relieved. In accordance with the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty, Orion and Conqueror were sold for scrap in 1922 and broken up the following year; Monarch was initially listed for sale, but was hulked instead. In 1923, she was converted into a target ship and was used to test the effects of bombs and shells, until she was sunk in early 1925. Thunderer was the last surviving ship and was sold in late 1926. On her way to the scrapyard, she ran aground at the entrance to the Port of Blyth, Northumberland, but was refloated and scrapped the following year.[23]

Notes

- Burt gives no account of Orion's activities between January 1912 and May 1916. This article assumes that the ship participated in the activities of the 2nd BS as Burt notes for Monarch.[23]

Citations

- Friedman 2015, p. 111

- Parkes, pp. 510, 525–526

- Brooks 1995, pp. 42–44; Friedman 2015, p. 114

- Brown, pp. 41–42

- Burt, p. 136

- Burt, pp. 136, 140

- Burt, p. 132; Friedman 2011, pp. 49–51, 62–63

- The Sight Manual ADM 186/216. Admiralty, Gunnery Branch. 1916. pp. 4, 29–31, 106, 109.

- Friedman 2011, pp. 49–52

- Parkes, p. 523

- Friedman 2011, pp. 97–98

- Brooks 1995, pp. 40–41

- Brooks 2005, p. 61

- Brooks 1996, pp. 163–165

- Brooks 2005, p. 48

- Brooks 1996, p. 168

- "Orion Class Battleship (1910)". The Dreadnought Project. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Brooks 2005, pp. 157–158, 175

- Burt, pp. 134, 136, 139

- Burt, pp. 136, 139

- Burt, pp. 140, 142; Friedman 2015, pp. 123, 198–199, 205

- Preston, p. 28

- Burt, pp. 146, 148, 150

- Massie, pp. 19, 69

- Halpern, p. 27

- Tarrant, pp. 28–30

- Goldrick, pp. 200–214

- Burt, pp. 148, 150

- Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- Corbett, p. 431 and frontispiece map

- Campbell, pp. 156–158, 193–195, 204–210, 218–220, 226–229, 276–277, 346–347

- Halpern, pp. 330–332

- Massie, p. 748

- "Operation ZZ". The Dreadnought Project. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. 1 March 1919. p. 10. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. 1 May 1919. p. 5. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 March 1920. pp. 707a. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "The Navy List" (PDF). National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 October 1920. pp. 695–6, 707a. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

Bibliography

- Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-40788-5.

- Brooks, John (1995). "The Mast and Funnel Question: Fire-control Positions in British Dreadnoughts". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship 1995. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 40–60. ISBN 0-85177-654-X.

- Brooks, John (1996). "Percy Scott and the Director". In McLean, David; Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 150–170. ISBN 0-85177-685-X.

- Brown, David K. (1999). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-315-X.

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- Corbett, Julian (1997) [1940]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. III (Second ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum in association with the Battery Press. ISBN 1-870423-50-X.

- Friedman, Norman (2015). The British Battleship 1906–1946. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-225-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company. OCLC 13614571.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament (New & rev. ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.

External links

- Dreadnought Project Technical material on the weaponry and fire control for the ships

- Orion Class Dreadnought Battleship