Ovillers-la-Boisselle in World War I

In World War I, the small commune of Ovillers-la-Boisselle, located some 22 miles (35 km) north-east of Amiens in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France, was the site of intense and sustained fighting between German and Allied forces. Between 1914 and 1916, the Western Front ran through the commune, and the villages were completely destroyed. After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, the former inhabitants returned and gradually rebuilt most of the infrastructure as it had been before the war.

The commune extends to the north and south of the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road, a former Roman road. The constituent village of Ovillers-la-Boisselle (commonly shortened to "Ovillers") lies to the north of the road. The constituent village of La Boisselle, which had 35 houses in 1914, lies to the south-west of Ovillers at the junction of the D 929 and the D 104 to Contalmaison. To avoid confusion, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in its documents referred to Ovillers-la-Boisselle north of the D 929 as "Ovillers" and to the village south of the road as "La Boisselle".[1]

Ovillers-la-Boisselle in 1914

In late September 1914, the villages of Ovillers and La Boisselle were first touched by the Great War when the German XIV Reserve Corps began operations west of Bapaume by advancing down the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road to the River Ancre, preparatory to an advance down the River Somme valley to Amiens.[2]

On 26 September, the French 11th Division attacked the invading Germans eastwards of Ovillers-la-Boisselle, but after French Territorial divisions were forced back from Bapaume, the division was ordered back to defend bridgeheads from Maricourt to Mametz.[3]

On 27 September, the II Bavarian Corps attacked between the River Somme and the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road, intending to reach the River Ancre and then continue westwards along the Somme valley. The 3rd Bavarian Division advanced close to Montauban and Maricourt, against scattered resistance from French infantry and cavalry.

On 28 September, the French were able to stop the German advance on a line from Maricourt to Fricourt and Thiepval,[2] which included halting the XIV Reserve Corps on the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road at La Boisselle.

In an attempt to capture Albert, the Germans planned a night attack on Bécourt, some 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) south of La Boisselle, for the evening of 7 October, but the infantry found that keeping direction in the dark was impossible. Small-arms fire from well dug-in French troops added to the confusion and the attack collapsed, 400 German troops being captured in the fiasco.[4]

On 19 November, two divisions of the French XI Corps attacked in the area of Ovillers and La Boisselle to pin down German troops, but were repulsed. On 28 November, an attack by the French XIV Corps managed to advance the French line by 300–400 metres (330–440 yd). In early December, the French IV Corps attacked around Ovilliers and gained 300–1,000 metres (330–1,090 yd). All in all, however, the French attacks were costly and gained little ground.[5] Ovillers and La Boisselle thus became part of the Western Front, a line that stretched from the North Sea to Switzerland and which remained essentially unchanged for most of the entire war.

From 17 December, attacks by the French 53rd Reserve Division of XI Corps took place at La Boisselle, Mametz, Carnoy and Maricourt.[6] Although wire-cutting had not been completed, the operation was ordered to begin at 6:00 a.m. without artillery support to gain a measure of surprise. The attack got beyond the German front line near Mametz and north of Maricourt and then repulsed German counter-attacks from Bernafay Wood and east of Mametz. The advance was contained by German reserves in the support lines and by flanking machine-gun fire. The 118th Battalion reached the cemetery of La Boisselle and the 19th Infantry Regiment closed on the western fringe of Ovillers. A German counter-bombardment then swept the ground west of Ovillers and Ravine 92, which prevented the approach of French reserves. During the night the French survivors of the attack fell back to the French front line, except at La Boisselle.[7] The next day, the French XI Corps broke through the German defences at La Boisselle cemetery but was stopped a short distance forward at L'îlot de La Boisselle, in front of trenches protected by barbed wire. A German counter-attack using incendiary grenades then recaptured a trench north of Maricourt, but at 10:30 a.m. a French counter-attack by two battalions of the 45th Infantry Regiment and a battalion of the 236th Infantry Regiment managed to regain a small amount of ground.[7]

On 24 December, the French 118th Infantry Regiment and two battalions of the 64th Infantry Regiment attacked again at La Boisselle at 9:00 a.m. after a bombardment. The 118th Regiment captured a small number of houses in the south-east of La Boisselle and consolidated the area during the night. The French 64th Regiment overran the German first line but was held up short of a second trench, which had not been discovered before the attack and then dug in, having lost many casualties.[7]

On 27 December, a German bombardment on the captured positions in La Boisselle was followed by a counter-attack on the French 118th and 64th Regiments, which was repulsed. German heavy artillery reinforcements had been brought into the area and made the area soon untenable; the French withdrew their infantry from La Boisselle but soon began to fortify their remaining positions with underground works.[7] A first mine shaft was sunk by French engineers on Christmas Day 1914. Many of the German units that had seen action on the Somme in 1914 remained in the area and made great efforts to fortify their defensive line, particularly with barbed-wire entanglements so that the front trench could be held with fewer troops. Railways, roads and waterways connected the battlefront to the Ruhr area of Germany, from where material for minierte Stollen (dug-outs) 20–30 feet (6.1–9.1 m) underground for 25 men each could excavated every 50 yards (46 m) and the front divided into Sperrfeuerstreifen (barrage sectors).[8]

As a result of the fighting, Ovillers and La Boisselle were completely destroyed. No man's land around the ruined villages varied from 50–800 yd (46–732 m) wide, L'îlot being the narrowest part. Once the location of a small number of houses in the south-east of La Boisselle, L'îlot became known as Granathof (German: "shell farm") to the Germans and later as Glory Hole to the British. As a result of the bloody and costly fighting for its occupation in late 1914, L'îlot quickly attained a profound symbolic status with the French Breton and German troops.[9]

Ovillers-la-Boisselle in 1915

January 1915 began frosty, which solidified the ground but wet weather followed and soon caused trenches and all other diggings to collapse, which made movement impossible after a few days, leading to tacit truces between the French and the Germans to allow supplies to be carried to the front line at night.[10] Having started mining at La Boisselle shortly after the French, the Bavarian Engineer Regiment 1 continued digging eight galleries towards L'îlot at the south end of the village. The L'îlot area would remain the scene of fierce underground fighting until the Battle of the Somme in July 1916.

On 18 January, the German Reserve Infantry Regiment 120 made a surprise attack on La Boisselle and destroyed the 7th and 8th Companies of the French 65th Infantry Regiment, taking 107 prisoners. Fighting took place at La Boisselle for the rest of the year.

On the night of 6/7 February, three more German mines were sprung close to L'îlot.[11] After the explosions, a large party of German troops advanced and occupied the demolished houses but were not able to advance further against French artillery and small-arms fire. At 3:00 p.m. a French counter-attack drove back the Germans and inflicted about 150 casualties. For several more days both sides detonated mines and conducted artillery bombardments, which often prevented infantry attacks.

On 1 March, German infantry massing for an attack at Bécourt – some 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) south of the ruins of La Boisselle – were stopped by French artillery, and on 15 March, a German mine was sprung at Carnoy and crater-fighting ensued for several days.[12] By comparison, sixty-one mines were sprung around L'îlot de La Boisselle from April 1915 – January 1916, some with 20,000–25,000 kilograms (44,000–55,000 lb) of explosives.[13]

In mid-July 1915, extensive Allied troop and artillery movements north of the River Ancre were seen by German observers. The type of shell fired by the enemy changed from high explosive to shrapnel, and unexploded shells were found to be of a different design. In early 1915, an informal live-and-let-live system between combat operations had developed between French and Germans soldiers, but from mid-July the soldiers facing the Germans did not continue the practice. In addition, a larger number of machine-guns began firing against the German lines, and the Germans observed that they did not pause every 25 shots like French Hotchkiss machine-guns. At first, the German troops were reluctant to believe that the British had assembled an army large enough to extend as far south as the Somme. An unidentified enemy soldier seen by German observers near Thiepval was thought to be a French soldier in a grey hat but by 4 August, it was officially reported by Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL: General Headquarters) that the 52nd Division and the 26th Reserve Division had seen a man in a brown suit. On 9 August, the arrival of the British Expeditionary Force became certain, when Private William Nicholson of the 6th Black Watch, 51st (Highland) Division was shot and captured during a German trench raid. A second British soldier was captured when 1st East Lancashire troops of the 4th Division were wiring in no man's land. The soldier got lost in fog near the River Ancre and blundered into the German lines near the Biber Kolonie ("beaver colony").[14]

During the summer months, the French mine workings in the area of Ovillers and La Boisselle were taken over by the Royal Engineers as the British moved into the Somme front and great secrecy was maintained to prevent the discovery of the mines. No continuous front line trench ran through L'îlot, which was defended by posts near the mine shafts.[15] After the Black Watch arrived at La Boissselle at the end of July, many existing trenches, originally dug by the French, were renamed by the Scottish troops which explains the presence of many Scotland-related names for the Allied fortifications in that front sector. In addition to digging defensive tunnels to obstruct German mining and creating offensive galleries aimed at destroying German fortifications, the Royal Engineers also dug deep wells to supply the troops with drinking water.

In August 1915, the French and Germans at La Boisselle were working at a depth of 12 metres (39 ft); the size of their charges had reached 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb). The British tunnelling companies dramatically increased the scale of mining operations by extending and deepening the system, first to 24 metres (79 ft) and ultimately 30 metres (98 ft). Above ground the infantry occupied trenches just 45 metres (148 ft) apart.[16] On 24 July 1915, 174th Tunnelling Company established headquarters at Bray, taking over some 66 shafts at Carnoy, Fricourt, Maricourt and La Boisselle. Around La Boisselle, the Germans had dug defensive transversal tunnels at a depth of about 80 feet (24 metres), parallel to the front line.[17] In October 1915, the 179th Tunnelling Company began to sink a series of deep shafts in an attempt to forestall German miners who were approaching beneath the British front line. At W Shaft they went down from 9.1 metres (30 ft) to 24 metres (80 ft) and began to drive two counter-mine tunnels towards the Germans. From the right-hand gallery at L'îlot, the sounds of German digging grew steadily louder.[16] On 19 November 1915, 179th Tunnelling Company's commander, Captain Henry Hance, estimated that the Germans were 15 yards away and ordered the mine chamber to be loaded with 2,700 kilograms (6,000 lb) of explosive. This was completed by midnight from 20–21 November. At 1.30 am on 22 November, the Germans blew their charge, filling the remaining British tunnels with carbon monoxide. Both the right and left tunnels were collapsed, and it was later found that the German blow had detonated the British charge. The wrecked tunnels were gradually re-opened, but about thirty bodies still lie in the tunnels beneath La Boisselle.[16][lower-alpha 1]

Ovillers-la-Boisselle in 1916

After the Herbstschlacht ("Autumn Battle", 25 September – 6 November 1915) the German defensive system on the Western Front was improved to make it more capable of withstanding Allied attacks with a relatively small garrison. Digging and wiring of yet another improved defence line in the area of Ovillers and La Boisselle began in May, French civilians were moved away and stocks of ammunition and hand-grenades were increased in the front-line.[18]

Fritz von Below, the commanding officer of the German 2nd Army, proposed a preventive attack in May and a reduced operation from Ovillers to St. Pierre Divion in June but got only one extra artillery regiment. On 6 June, he reported that an imminent Allied offensive at Fricourt and Gommecourt was indicated by air reconnaissance and that the south bank had been reinforced by the French, against whom his XVII Corps was overstretched with twelve regiments to hold 36 kilometres (22 mi) without reserves.[19]

Battle of the Somme

At the start of the Battle of Albert (1–13 July), the name given by the British to the first two weeks of the Battle of the Somme, the ruined villages of Ovillers and La Boisselle found themselves at the very epicentre of events, with the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road marking the main axis of the British attack.

German fortifications

In June 1916, the German positions in the area of Ovillers and La Boisselle lay across several salients and re-entrants on the forward slope of a low ridge between La Boisselle and Albert, which was a continuation of the south-west spur from the main Bazentin Ridge on which Ovillers had been built. The German defences ran along the higher slopes of three spurs (Fricourt Spur, La Boisselle Spur, Ovillers Spur), which descend south-west from the main ridge. With the exception of L'îlot, now a crater field just west of the ruins of La Boisselle, each German trench had an unmistakable white chalk parapet which could be seen from the British lines. Two geological depressions between the spurs were known as Sausage Valley and Mash Valley, which were about 1,000 yards (910 m) wide at their broadest points, making an enemy advance up them vulnerable to cross-fire. The spurs were covered by trench networks and machine-gun posts.[20] No man's land varied from 50–800 yards (46–732 m) wide, the narrowest part opposite La Boisselle being L'îlot. The D 929 Albert–Bapaume road descended westwards from Pozières, then down the north side of the La Boisselle Spur as far as the front lines, then beyond to Albert.[21]

The German fortifications in the Ovillers and La Boisselle area began with a defensive system which had four strong points in the southern section, Helgoland (Sausage Redoubt) backed by Schwabenhöhe (Scots Redoubt) and a garrison in the ruins of La Boisselle.[21] The front defensive system was held by two battalions of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 of the 28th (Baden) Reserve Division, with a third battalion in reserve in the intermediate lines and the second position.[22] The ruins of Ovillers had also been fortified. An intermediate front line ran from Fricourt Farm to Ovillers, and a second intermediate line in front of Contalmaison and Pozières was under construction. Behind this front position, a second position with two parallel trenches ran from Bazentin-le-Petit to Mouquet Farm. A third position ran about 3 miles (4.8 km) behind the second position.[21] The German defences in the Ovillers and La Boisselle sectors were mostly on a forward slope lined by white chalk, easy to see and to bombard by the enemy, but the natural spurs and re-entrants were excellent defensive features.[20] The German fortifications were crowded towards the front trench, where deep dug-outs with plenty of overhead protection had been built. In addition, the German defences in the Ovillers sector had only recently been improved. There were deep fields of barbed wire covered by machine-gun posts and many communication trenches, which made quick movement within the position possible and could be used to contain a penetration of the front line.[23]

British preparations

On the Allied side, the front line from Bécourt to Authuille was held by the British III Corps under Lieutenant-General William Pulteney. In dead ground behind the low ridge between La Boisselle and Albert (see above), field artillery was deployed in rows and the British artillery observers on the ridge had a perfect view of the German front position. The right flank of the III Corps was opposite Fricourt Spur, the centre of the Corps faced La Boisselle Spur (with the village ruins just behind the front line) and the left flank of the Corps was west of Ovillers Spur. Thiepval Spur to the north, opposite the British X Corps, overlooked the ground across which the III Corps divisions must advance.[20]

Assembled nearby, 5 miles (8.0 km) west of Albert, stood the British Reserve Army under Lieutenant-General Hubert Gough, which was to advance once the roads had been cleared by the first attack.[24] Gough had the 1st, 2nd Indian and 3rd Cavalry Divisions as well as the 12th and 25th infantry divisions, all ready to advance through any gap formed in the enemy defences and then to turn north towards Bapaume, chasing the Germans as they retreated.[25]

On the left flank of III Corps, the 8th Division was to attack against the Ovillers Spur, which dominates the ground north of the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road. It faced a stretch of no man's land that was unusually wide, particularly on the right towards the ruins of La Boisselle, where both front lines bent back.[26] One brigade would move up Mash Valley, with the right flank to gain the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road south of Ovillers, and then advance 1 mi (1.6 km) up the road to Pozières. The centre brigade was to capture the ruined village of Ovillers itself. The third brigade was to attack the south slope of Nab Valley to the north of Ovillers, and then march to the north of Pozières.[27] During the attack, the 8th Division's centre brigade would be able to benefit from a naturally covered approach until the last 300–400 yd (270–370 m) up to Ovillers. The flanking brigades would have to advance up the re-entrants of Mash Valley to the south and Nab Valley further to the north, fully exposed on flat ground without cover to the German garrisons in La Boisselle and the Leipzig salient.[26][lower-alpha 2]

On the right flank of III Corps, the 34th Division, composed of Pals battalions, was to capture the German positions on the Fricourt Spur and Sausage Valley to the far side of La Boisselle, and then advance to a line about 800 yards (730 m) short of the German second line from Contalmaison to Pozières. The division would have to capture the fortified ruins of La Boisselle as well as six German trench lines, and complete a 2-mile (3.2 km) advance on a 2,000 yards (1,800 m) front. The 19th Division in the III Corps' reserve was to move forward to vacated trenches in the line of the Tara and Usna hills, ready to relieve the attacking divisions after their objectives had been reached.[28] If the German defences collapsed, both the 19th and 49th Divisions (in reserve) were to advance either side of the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road under the command of the Reserve Army.[29] Many of the British infantry in the sector had been coal miners before 1914 and dug an elaborate complex of underground galleries in Tara hill to shelter the assembled battalions.[30]

Plan of attack

The Allied attack on the German front line along the Somme battlefield was to be preceded by a seven-day preliminary bombardment with heavy artillery. The infantry advance at Zero Hour was also to be accompanied by a flexible artillery barrage which would move back slowly on a timetable. The heavy guns were to fire on the German defences in eight "lifts", jumping from one defence line to the next. The III Corps artillery in the area of Ovilliers and La Boisselle had 98 heavy guns and howitzers and a groupe of the French 18th Field Artillery Regiment was to fire gas shells. The III Corps artillery was divided into two field artillery groups for each attacking division and a fifth group, containing the heaviest artillery, to cover all the corps front. According to the Allied plans, there was one heavy gun for each 40 yards (37 m) of front and a field gun for every 23 yards (21 m). The artillery was supported by most of 3 Squadron Royal Flying Corps for artillery observation and reconnaissance sorties.[31]

Going over the top at 7:30 a.m., the British infantry was to attack in waves. Four columns, three battalions deep, were to attack on 400 yards (370 m) frontages, with a gap between the third and fourth columns on either side of La Boisselle, which was not to be attacked directly[32] as the Germans had strongly fortified the cellars of the ruined houses and the deeply-cratered ground at L'îlot made direct assault on the village impossible. As part of the Allied preparations, two mines with 3,600-kilogram (8,000 lb) charges (known as No 2 straight and No 5 right) were planted at L'îlot at the end of galleries dug from Inch Street Trench by the 179th Tunnelling Company. To assist the attack on the ruined village, two further mines, known as Y Sap and Lochnagar after the trenches from which they were dug, were placed to the north-east and the south-east of La Boisselle.[16]

The infantry columns were to advance in lines of companies in extended order, the companies moving in platoon columns 150 paces apart.[30] As the columns passed by the heavily fortified German salient at La Boisselle, bombing parties supported by Lewis gun and Stokes mortar crews were to attack from both flanks.

When the British battalion and brigade commanders ventured to doubt the viability of the plan, they were reminded that the week-long preliminary bombardment before the battle would have killed the village garrison by the time of the attack and that the mine explosions would destroy any remaining fortifications on either side of the La Boisselle salient.[32] However, during the preliminary bombardment of the Ovillers and La Boisselle area, the III Corps artillery was hampered by poor-quality ammunition, which caused premature shell-explosions in gun barrels and casualties to the gunners. Many howitzer shells fell short and there was a large number of blinds (duds). The unsatisfactory bombardment and the discovery on 30 June that parties clearing paths through the British wire had been fired on by the German garrison in the ruins of La Boisselle, led to an additional battery of eight Stokes mortars being readied to bombard La Boisselle at Zero Hour until the flanking parties had entered the ruined village. Sausage Redoubt (Helgoland) was to be bombarded by Stokes mortars from an emplacement dug in no man's land overnight, 500 yards (460 m) opposite the strong point.[28]

Underground

The tunnelling companies were to make two major contributions to the Allied preparations for the battle by placing 19 large and small mines beneath the German positions along the front line and by preparing a series of shallow Russian saps from the British front line into no man's land, which would be opened at Zero Hour and allow the infantry to attack the German positions from a comparatively short distance.[33] Russian saps in front of Thiepval, Ovillers and La Boisselle were the task of 179th Tunnelling Company.[34]

Four mines were dug in the Ovillers-la-Boisselle sector: Two 3,600-kilogram (8,000 lb) charges (known as No 2 straight and No 5 right) were planted at L'îlot at the end of galleries dug from Inch Street Trench by the 179th Tunnelling Company, intended to wreck German tunnels[35] and create crater lips to block enfilade fire along no man's land. To assist the attack on the village, two further mines, known as Y Sap and Lochnagar after the trenches from which they were dug, were laid to the north-east and the south-east of La Boisselle on either side of the German salient[16][17] – see map. The tunnel for the Lochnagar mine was excavated at a rate of about 18 inches (46 cm) per day, until about 1,030 feet (310 m) long. The tunnel for the Y Sap mine started in the British front line near where it crossed the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road, but because of German underground defences it could not be dug in a straight line. About 500 yards (457 metres) were dug into no-mans-land before it turned right for about another 500 yards (457 metres).[17] Lochnagar was loaded with 60,000 pounds (27,000 kg) of ammonal, in two charges of 36,000 pounds (16,000 kg) and 24,000 pounds (11,000 kg), 60 feet (18 m) apart and 52 feet (16 m) deep. Just north of the ruined village, the Y Sap mine was charged with 40,600 pounds (18,400 kg) of ammonal.[36] All of these mines were laid without interference by German miners but as the explosives were placed, German miners could be heard below the Lochnagar and above the Y Sap mines.[36] Communication tunnels were also dug for use immediately after the first attack on 1 July 1916, but were little used in the end.[17]

Events 1 to 16 July

The fight for the ruins of La Boisselle and Ovilliers was to begin in the morning of Saturday 1 July 1916, the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. The British Fourth and Third armies, together with nine corps of the French Sixth Army, would attack the German 2nd Army in an area stretching from Foucaucourt south of the River Somme northwards beyond the River Ancre, to Serre and Gommecourt, 3.2 kilometres (2 mi) beyond. The objective of the attack was to capture the German first and second positions from Serre south to the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road and the first position from the road south to Foucaucourt.

At 7:28 a.m. the Royal Engineers detonated their four mines at La Boisselle, and 15 other mines were fired along other sectors of the front line. The explosion of the Lochnagar mine obliterated 91–122 metres (300–400 ft) of German fortifications,[37] including nine dug-outs and the men inside them. Most of the 5th Company of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 and the trenches nearby were destroyed.[37] The Lochnagar mine lay on the sector assaulted by the Grimsby Chums, a Pals battalion (10th Battalion, The Lincolnshire Regiment).[38] When the main attack began at Zero Hour, the Grimsby Chums occupied the crater and began to fortify the eastern lip, which dominated the vicinity and the advance continued to the Grüne Stellung (second position), where it was stopped by the German 4th Company, which then counter-attacked and forced the British back to the crater.[37]

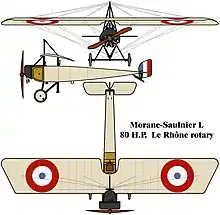

The blowing of the Lochnagar and Y Sap mines was witnessed by pilots who were flying over the battlefield to report back on British troop movements. It had been arranged that continuous overlapping patrols would fly throughout the day. 2nd Lieutenant Cecil Lewis' patrol of 3 Squadron was warned against flying too close to La Boisselle, where two mines were due to go up, but would be able to watch from a safe distance. Flying up and down the line in a Morane Parasol, he watched from above Thiepval, almost two miles from La Boisselle, and later described the early morning scene in his book Sagittarius Rising (1936):

We were over Thiepval and turned south to watch the mines. As we sailed down above all, came the final moment. Zero! At Boisselle the earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up into the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar, drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earthly column rose, higher and higher to almost four thousand feet. There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like a silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris. A moment later came the second mine. Again the roar, the upflung machine, the strange gaunt silhouette invading the sky. Then the dust cleared and we saw the two white eyes of the craters. The barrage had lifted to the second-line trenches, the infantry were over the top, the attack had begun.

Despite their colossal size, the Lochnagar and Y Sap mines failed to help sufficiently neutralise the German defences in the village, and the German troops had deep shelters that withstood the British artillery fire. The preparatory seven-day artillery bombardment had cut much of the German trench wire but the field fortifications beyond were far less affected, particularly the deep dugouts succeeded in keeping the German garrisons comparatively safe. The German losses through the bombardment remained miraculously low, and the mood of the men in their underground shelters was "splendid".[41]

The British infantry attack on Ovillers and La Boisselle was launched at Zero Hour (7:30 a.m.) by the III Corps, its 34th Division attempting the capture of La Boisselle and its 8th Division attempting the capture of Ovillers. The British attack turned into a disaster: La Boisselle was meant to fall in 20 minutes, but by the end of the first day of the battle, neither La Boisselle nor Ovillers had been taken while the III Corps divisions had lost more than 11,000 casualties. At Mash Valley, the attackers lost 5,100 men before noon, and at Sausage Valley near the crater of the Lochnagar mine, there were over 6,000 casualties – the highest concentration on the entire battlefield. The III Corps' 34th Division suffered the worst losses of any unit that day.[16]

| Date | Rain mm |

Temp (°F) |

Outlook |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0 | 75°–54° | clear hazy |

| 2 | 0.0 | 75°–54° | clear fine |

| 3 | 2.0 | 68°–55° | fine |

| 4 | 17.0 | 70°–55° | thunder storms |

| 5 | 0.0 | 72–52° | low cloud |

| 6 | 2.0 | 70°–54° | showers |

| 7 | 13.0 | 70°–59° | showers |

| 8 | 8.0 | 73°–52° | rain |

| 9 | 0.0 | 70°–53° | cloudy |

| 10 | 0.0 | 82°–48° | overcast |

| 11 | 0.0 | 68°–52° | overcast |

| 12 | 0.1 | 68°–? | overcast |

| 13 | 0.1 | 70°–54° | overcast |

| 14 | 0.0 | 70°–? | overcast |

| 15 July | 0.0 | 72°–47° | bright |

| 16 July | 4.0 | 73°–55° | dull |

| 17 July | 0.0 | 70°–59° | misty |

The III Corps only managed to gain small footholds to the south of La Boisselle, near the boundary with XV Corps, and at Schwabenhöhe, where the explosion of the Lochnagar mine had destroyed some of the German defences. Details of the costly defeat of most British attacks north of the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road were not known on the evening of 1 July. General Sir Douglas Haig ordered that the attack resume as soon as possible, and the III Corps was instructed to capture La Boisselle and Ovillers, then capture Contalmaison, and then to establish a defensive flank between the ruined villages. The 8th Division was withdrawn from Ovillers and replaced by the 12th Division, which resumed the attack on 3 July.

At La Boisselle, the British captured the German front line trench on 2 July, occupied the west end of the ruined village by 9:00 p.m. and dug in near the church. The next day, the British gradually managed to drive the German units from what was left of La Boisselle, although the German underground fortifications had withstood the recent bombardments and British attempts to signal with flares that La Boisselle had been captured had led to the German artillery bombarding the ruined village with howitzers and mortars, followed by an infantry counter-attack which drove the British back from the east end of La Boisselle. Reinforcements went forward and eventually a line was stabilised through the church ruins, about 100 yards (91 m) beyond the start line of the British attack. After dark on 3 July, the 23rd Division began to relieve the 34th Division, which had lost 6,811 men at La Boisselle from 1–5 July. The 19th Division was rushed forward from reserve, continued the attack at the east side of La Boisselle and captured most of the village ruins by 4 July. The retreating Germans launched three counter-attacks but were defeated, and the capture of La Boisselle was completed by 6 July.

At Ovillers, the 12th Division had resumed the attack on 3 July. A preparatory bombardment began at 2:12 a.m. against the same targets as on 1 July, but with additional support from the 19th Division's artillery near La Boisselle. Attacking at 3:15 a.m., the British found enough gaps in the German wire to enter the enemy trenches, but German infantry emerged from dug-outs to counter-attack from behind. At dawn, most of the units which had reached the German line were overwhelmed and the last British foothold on the edge of Ovillers was lost shortly thereafter. On 7 July, units of the 12th Division advanced on the ruins of Ovillers but were stopped at the first German trench by continuous machine-gun fire. Before dawn on 9 July, the 12th Division – which had lost 4,721 casualties since 1 July[43] – was relieved by the 32nd Division. From 9–10 July, three battalions of the 32nd Division's 14th Brigade managed to advance a short distance on the left side of Ovillers, and the British continued attacks during the night of 13/14 July. At 2:00 a.m. on 15 July, units of the 25th and the 32nd Divisions attacked Ovillers again, but were repulsed by the German garrison. The next day, the 25th Division attacked at 1:00 a.m. and captured the ruined village, the last Germans surrendering during the evening.

After the opening phase of the Battle of the Somme, the ruins of Ovillers and La Boisselle remained a relatively quiet sector of the front until spring 1918.

Ovillers-la-Boisselle in 1918

The ruins of Ovillers and La Boisselle were re-captured by the Germans on 25 March 1918, after a retreat by the 47th Division and the 12th (Eastern) Division during Operation Michael, the German spring offensive.[44][45][46] In the afternoon, air reconnaissance saw that the British defence of the line from Montauban and Ervillers was collapsing and the RFC squadrons in the area made a maximum effort to disrupt the German advance.[47] During the Second Battle of Bapaume (21 August – 3 September 1918), the German garrison in the ruins of Ovillers resisted an attack on 24 August but were by-passed on both flanks two days later by the 38th Division and retreated before they could be surrounded.[48] Ovillers and La Boisselle were thus recaptured for the last time.[49][50]

Commemoration

- Ovillers British Military Cemetery

- The Gordon Dump Cemetery

- Lochnagar Crater

Gallery

German trench occupied by the 9th Cheshires, La Boisselle, July 1916

German trench occupied by the 9th Cheshires, La Boisselle, July 1916 Daily Mail Postcard: Captured dug-out near La Boisselle

Daily Mail Postcard: Captured dug-out near La Boisselle La Boisselle mine crater, August 1916

La Boisselle mine crater, August 1916 Troops passing Lochnagar Crater, October 1916

Troops passing Lochnagar Crater, October 1916 Lochnagar Crater, October 2005

Lochnagar Crater, October 2005 Lochnagar Crater, August 2006

Lochnagar Crater, August 2006

Notes

- See also The real hero tunnellers of World War One who inspired BBC's Birdsong, www.mirror.co.uk, 21 January 2012 (online), access date 6 July 2015, where the date of the detonation is given with 22 October 1915.

- The 8th Division's commanding officer, Havelock Hudson, asked for the divisional zero hour to be postponed slightly so that the 34th Division to the south and the 32nd Division to the north would have engaged these positions before the infantry advanced. Rawlinson rejected the request but put a battery of the 32nd Division artillery at the disposal of the 8th Division to suppress enfilade fire.[26]

References

- Gliddon 1987, p. 248.

- Sheldon 2005, pp. 22–26.

- Philpott 2009, p. 28.

- Sheldon 2005, p. 38.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 46, 114.

- The Times 1916, p. 9.

- Chtimiste 2003.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 57–58.

- The La Boisselle Project: project details, access date: 4 November 2016

- Sheldon 2005, p. 56.

- Sheldon 2005, p. 62.

- The Times 1916, pp. 9, 39.

- Sheldon 2005, pp. 63–65.

- Whitehead 2013, p. 290.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 38.

- Banning et al. 2011.

- Dunning 2015.

- Philpott 2009, pp. 157–165.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 316–317.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 371–372.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 372.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 376.

- Whitehead 2013, pp. 254–257.

- Edmonds & Wynne 1932, pp. 150–151.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 267.

- Boraston & Bax 1999, pp. 86–70.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 385.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 372–373.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 307.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 376–377.

- Jones 2002, p. 212.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 375–376.

- Jones 2010, p. 115.

- Jones 2010, p. 202.

- Shakespear 1921, p. 37.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 375.

- Whitehead 2013, p. 297.

- Legg 2013.

- Lewis 1936, p. 90.

- Gilbert 2007, p. 54.

- Whitehead 2013, p. 255.

- Gliddon 1987, pp. 415–417.

- Miles 1992, pp. 41–42.

- Edmonds, Davies & Maxwell-Hyslop 1935, pp. 480–481.

- Maude 1922, pp. 163–165.

- Middleton Brumwell 1923, pp. 169–170.

- Jones 1934, p. 319.

- Edmonds 1947, pp. 243, 249–250.

- Edmonds 1947, pp. 238–242.

- Munby 1920, p. 51.

Bibliography

Books

- Boraston, J. H.; Bax, C. E. O. (1999) [1926]. The Eighth Division in War 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Medici Society. ISBN 978-1-897632-67-3.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (2010) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1916: Appendices. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-84574-730-5.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Davies, H. R.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1995) [1935]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-219-7.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1947]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: 8th August – 26th September The Franco-British Offensive. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. IV (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-191-6.

- Gilbert, M. (2007). Somme: The Heroism and Horror of War. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6890-9.

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 978-0-947893-02-6.

- Harris, J. P. (2009) [2008]. Douglas Haig and the First World War (reprint ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. Vol. II (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1934]. The War in the Air Being the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. IV (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-415-4. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914-1918. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Lewis, C. A. (1977) [1936]. Sagittarius Rising: The Classic Account of Flying in the First World War (2nd Penguin ed.). London: Peter Davis. ISBN 978-0-14-004367-9. OCLC 473683742.

- Maude, A. H., ed. (1922). The 47th (London) Division, 1914–1919 by Some who Served With it in the Great War. London: Amalgamated Press. OCLC 494890858. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Middleton Brumwell, P. (2001) [1923]. Scott, A. B. (ed.). History of the 12th (Eastern) Division in the Great War, 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Nisbet. ISBN 978-1-84342-228-0. OCLC 6069610. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Miles, W. (1992) [1938]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916, 2nd July 1916 to the End of the Battles of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-901627-76-6.

- Munby, J. E., ed. (2003) [1920]. A History of the 38th (Welsh) Division: By the GSO's.I of the Division (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Hugh Rees. ISBN 1-84342-583-1. OCLC 495191912. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the Making of the Twentieth Century. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (2005). The Somme. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10694-7.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Shakespear, J. (2001) [1921]. The Thirty-Fourth Division, 1915–1919: The Story of its Career from Ripon to the Rhine (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: H. F. & G. Witherby. ISBN 1-84342-050-3. OCLC 6148340. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2006) [2005]. The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-1-84415-269-8.

- Whitehead, R. J. (2013). The Other Side of the Wire: The Battle of the Somme. With the German XIV Reserve Corps, 1 July 1916. Vol. II. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-907677-12-0.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

- Wyrall, E. (2009) [1932]. The Nineteenth Division 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-1-84342-208-2.

Encyclopedias

- The Times History of the War. 1916. OCLC 642276. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Websites

- Banning, J. (2011). "Tunnellers". La Boisselle Study Group. et al. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Logier, D. (2003). "La reprise de l'offensive fin 1914–début 1915". Historiques des Régiments 14/18 (in French). Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Dunning, R. (2015). "Military Mining". Lochnagar Crater. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Legg, J. "Lochnagar Mine Crater Memorial, La Boisselle, Somme Battlefields". www.greatwar.co.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

Further reading

Books

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations, France and Belgium: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne, August – October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 604621263.

- Sandilands, H. R. (1925) [2003]. The 23rd Division 1914–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). Edinburgh: Wm. Blackwood. ISBN 1-84342-641-2.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.

Theses

- Simpson, A. (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (PhD). London: London University. OCLC 59484941. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

Websites

- Legg, J. "Lochnagar Mine Crater Memorial, La Boisselle, Somme Battlefields". www.greatwar.co.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2013.