Pataliputra

Pataliputra (IAST: Pāṭaliputra), adjacent to modern-day Patna,[1] was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE, as a small fort (Pāṭaligrāma) near the Ganges river.[2][3] Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at the confluence of two rivers, the Son and the Ganges. He shifted his capital from Rajgriha to Pataliputra due to the latter's central location in the empire.

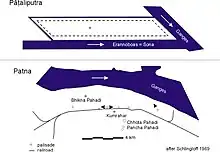

Plan of Pataliputra, compared to present-day Patna | |

Shown within India  Pataliputra (Bihar) | |

| Alternative name | Pātaliputtā (Pāli) |

|---|---|

| Location | Patna district, Bihar, India |

| Region | South Asia |

| Coordinates | 25°36′45″N 85°7′42″E |

| Altitude | 53 m (174 ft) |

| Length | 14.5 km (9.0 mi) |

| Width | 2.4 km (1.5 mi) |

| History | |

| Builder | Ajatashatru |

| Founded | 490 BCE |

| Abandoned | Became modern Patna |

| Associated with | Haryankas, Shishunagas, Nandas, Mauryans, Shungas, Guptas, Palas |

| Management | Archaeological Survey of India |

| Pilgrimage to |

| Buddha's Holy Sites |

|---|

|

It became the capital of major powers in ancient India, such as the Shishunaga Empire (c. 413–345 BCE), Nanda Empire (c. 460 or 420 – c. 325 BCE), the Maurya Empire (c. 320–180 BCE), the Gupta Empire (c. 320–550 CE), and the Pala Empire (c. 750–1200 CE). During the Maurya period (see below), it became one of the largest cities in the world. As per the Greek diplomat, traveler and historian Megasthenes, during the Mauryan Empire (c. 320–180 BCE) it was among the first cities in the world to have a highly efficient form of local self government.[4] The location of the site was first identified in modern times in 1892 by Laurence Waddell, published as Discovery Of The Exact Site Of Asoka's Classic Capital.[5] Extensive archaeological excavations have been made in the vicinity of modern Patna.[6][7] Excavations early in the 20th century around Patna revealed clear evidence of large fortification walls, including reinforcing wooden trusses.[8][9]

Etymology

In the Sanskrit language, "Pāṭali-" refers to the pāṭalī tree (Bignonia suaveolens),[10] while "-putrá" (पुत्र) means "son".

One traditional etymology[11] holds that the city was named after the plant.[12] Indeed, according to the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta (Sutta 16 of the Dīgha Nikāya), Pāṭaliputta was the place "where the seedpods of the Pāṭali plant break open".[13] Another tradition says that Pāṭaliputra means the son of Pāṭali, who was the daughter of a certain Raja Sudarsan.[14] As it was originally known as Pāṭali-grāma ("Pāṭali village"), some scholars believe that Pāṭaliputra is a transformation of Pāṭalipura, "Pāṭali town".[15] Pataliputra was also called Kusumapura (city of flowers).

History

There is no mention of Pataliputra in written sources prior to the early Jain and Buddhist texts (the Pali Canon and Āgamas), where it appears as the village of Pataligrama and is omitted from a list of major cities in the region.[16] Early Buddhist sources report a city being built in the vicinity of the village towards the end of the Buddha's life; this generally agrees with archaeological evidence showing urban development occurring in the area no earlier than the 3rd or 4th Century BCE.[16] In 303 BCE, Greek historian and ambassador Megasthenes mentioned Pataliputra as a city in his work Indika.[17]Diodorus, quoting Iambulus mention that the king of Pataliputra had a " great love for the Greeks ".[18]

The city of Pataliputra was formed by fortification of a village by Haryanka ruler Ajatashatru, son of Bimbisara.[19]

Its central location in north eastern India led rulers of successive dynasties to base their administrative capital here, from the Nandas, Mauryans, Shungas and the Guptas down to the Palas.[20] Situated at the confluence of the Ganges, Gandhaka and Son rivers, Pataliputra formed a "water fort, or jaldurga".[21] Its position helped it dominate the riverine trade of the Indo-Gangetic plains during Magadha's early imperial period. It was a great centre of trade and commerce and attracted merchants and intellectuals, such as the famed Chanakya, from all over India.

Two important early Buddhist councils are recorded in early Buddhist texts as being held here, the second session of the Second Buddhist council in the reign of Ashoka, 35 years after the first session held in Vaisali and the Third Buddhist council.[22]

Jain and Hindu sources identify Udayabhadra, son of Ajatashatru, as the king who first established Pataliputra as the capital of Magadha.[16] The Sangam Tamil epic Akanaṉūṟu mentions Nanda kings ruling Pataliputra.[23][24][25]

Capital of the Maurya Empire

During the reign of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE, it was one of the world's largest cities, with a population of about 150,000–400,000.[26] The city is estimated to have had a surface of 25.5 square kilometers, and a circumference of 33.8 kilometers, and was in the shape of a parallelogram and had 64 gates (that is, approximately one gate every 500 meters).[27] Pataliputra reached the pinnacle of prosperity when it was the capital of the great Mauryan Emperors, Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka.

"They surpass in power and glory every other people, not only in this quarter, but one may say in all India, their capital being Palibothra, a very large and wealthy city, after which some call the people itself the Palibothri, - nay, even the whole tract along the Ganges. Their king has in his pay a standing army of 600,000 foot-soldiers, 30,000 cavalry, and 9000 elephants : whence may be formed some conjecture as to the vastness of his resources." Megasthenes, in Indica[28]

The city prospered under the Mauryas and a Greek ambassador, Megasthenes, resided there and left a detailed account of its splendour, referring to it as "Palibothra":

"Megasthenes says that on one side where it is longest this city extends ten miles in length, and that its breadth is one and threequarters miles; that the city has been surrounded with a ditch in breadth 600 feet, and in depth 45 feet; and that its wall has 570 towers and 64 gates." - Arrian "The Indica"[29]

Strabo in his Geographia adds that the city walls were made of wood. These are thought to be the wooden palisades identified during the excavation of Patna.[30]

"At the confluence of the Ganges and of another river is situated Palibothra, in length 80, and in breadth 15 stadia. It is in the shape of a parallelogram, surrounded by a wooden wall pierced with openings through which arrows may be discharged. In front is a ditch, which serves the purpose of defence and of a sewer for the city." - Strabo, "Geographia"[31]

Aelian, although not expressly quoting Megasthenes nor mentioning Pataliputra, described Indian palaces as superior in splendor to Persia's Susa or Ecbatana:

"In the royal residences in India where the greatest of the kings of that country live, there are so many objects for admiration that neither Memnon's city of Susa with all its extravagance, nor the magnificence of Ecbatana is to be compared with them. (...) In the parks, tame peacocks and pheasants are kept." - Aelian in "De Natura Animalium"[32]

Under Ashoka, most of wooden structure of Pataliputra palace may have been gradually replaced by stone.[33] Ashoka was known to be a great builder, who may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments.[34] Pataliputra palace shows decorative influences of the Achaemenid palaces and Persepolis and may have used the help of foreign craftmen.[35] Which may be the result of the formative influence of craftsmen employed from Persia following the disintegration of the Achaemenid Empire after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[36][37]

Capital of later dynasties

The city also became a flourishing Buddhist centre boasting a number of important monasteries. It remained the capital of the Gupta dynasty (3rd–6th centuries) and the Pala Dynasty (8th-12th centuries). When Faxian visited the city in 400 A.D, he found the people to be rich and prosperous; they practised virtue and justice.[38] He found that the nobles and householders of the city had constructed several hospitals in which the poor of all countries, the destitute, the crippled and the diseased can get treatment. They could receive every kind of help gratuitously. Physicians would inspect the diseases, and order them food, drink, and medicines.[39]

Decline

When Xuanzang visited Pataliputra in the year 637, he found the city in ruins. He wrote that the old city had been completely deserted for many years, and all that was left was a small walled town by the bank of the Ganges, home to no more than about 1,000 people. According to Rajeshwar Prasad Singh, this small town had probably been built after the old city's destruction, as opposed to being a surviving part of the old town. Xuanzang wrote that most of the city's old historic buildings had been destroyed, and only their foundation walls remained. One building he noted in particular was an old stupa that was said to be the first of the 84,000 stupas built by Ashoka. Its foundation had sunken into the ground so that only the ornamental top of the dome was visible, and even that was in precarious condition, he wrote. Of the Kukkuṭārāma monastery on the southeast side of the city, only the foundation remained.[40]: 12 [41]: 53–4 [42]: 4

Pataliputra's decline had probably begun well before Xuanzang's time. At least at Kumrahar, archaeological evidence seems to suggest a gradual decline beginning in the 300s, with fewer and less elaborate structures between this period and c. 600. After that, there are no traces of human activity for a thousand years, and the site seems to have been abandoned.[41]: 53

One likely contributing factor was a shift in the course of the Ganges. As early as Faxian's visit around the year 400, he wrote that Pataliputra was one yojana (about 10 km) south of the Ganges. The Varāha Purāṇa, from post-Gupta times, indicates that the confluence of the Gandak and the Ganges was then about 10 km north of the present location. Since Pataliputra derived a lot of its prosperity from river-based commerce, being separated from the river probably dampened its economy. A general decline in international trade toward the end of the Gupta period would have had a similar effect.[41]: 56

A catastrophic flood likely also devastated the city at some point in the late 500s. A later Jain work, the Titlhogali Painniya, records a traditional account of a disastrous flood on the Son River destroying Pataliputra at some point. This account describes this flood as happening during the month of Bhādrapada, or September, after 17 days and nights of heavy rain. The flooding on the Son apparently caused the Ganges to overflow as well, and Pataliputra was inundated on multiple sides. The account describes widespread destruction in Pataliputra, although it also says that the city was rebuilt afterwards.[40]: 12 [41]: 56–7

A third possible contributing factor is deliberate destruction by invading Hunas in the early 500s. A thick layer of ashes found at the 80-pillar hall at Kumrahar suggests that the building may have been destroyed by fire, possibly corroborating this theory.[41]: 54, 57

Pala dynasty

Pataliputra seems to have recovered somewhat by the early Pala period. The Khalimpur plate of Dharmapala, from the early 800s, gives a vivid description of Pataliputra as a river port and royal encampment. It describes the crowds of boats, elephants, horses, and "limitless foot-soldiers of all the kings of Jambudvīpa assembled to render homage" to Dharmapala. B. P. Sinha interpreted this inscription to mean that Pataliputra was Dharmapala's capital, but A. S. Altekar disputed this, saying that the inscription only refers to Pataliputra as a skandhāvāra, or camp, where Dharmapala stayed while on a campaign or tour.[40]: 13

While Pataliputra is mentioned in contemporary sources, archaeologists have not found any evidence from the Pala period at Pataliputra. At least at Kumrahar, there are no traces of human settlement until the 1600s.[42]: 5, 8

1500s

In a fanciful 1559 book about world geography, the Italian Caius Julius Solinus briefly mentions a powerful Indian kingdom of Prasia with a capital at Palibotra.[43] Afterwards, Sher Shah Suri made Pataliputra his capital and changed the name to modern Patna.

Structure

Though parts of the ancient city have been excavated, much of it still lies buried beneath modern Patna. Various locations have been excavated, including Kumhrar, Bulandi Bagh and Agam Kuan.

During the Mauryan period, the city was described as being shaped as parallelogram, approximately 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) wide and 15 kilometers (9 miles) long. Its wooden walls were pierced by 64 gates. Archaeological research has found remaining portions of the wooden palisade over several kilometers, but stone fortifications have not been found.[44]

Excavated sites of Pataliputra

As dynastic capital

- Pataliputra served as the capital under various Indian dynasties

.png.webp) Pataliputra served as the capital of the Haryanka dynasty and the Shishunaga dynasty of Magadha

Pataliputra served as the capital of the Haryanka dynasty and the Shishunaga dynasty of Magadha Pataliputra served as the capital of the Nanda Empire

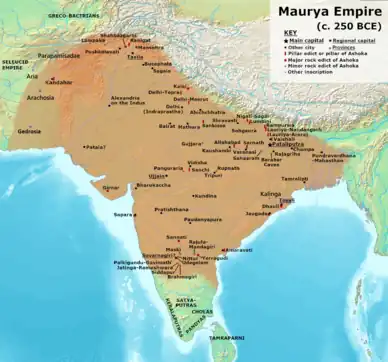

Pataliputra served as the capital of the Nanda Empire Pataliputra served as the capital of the Maurya Empire

Pataliputra served as the capital of the Maurya Empire Pataliputra served as the capital of the Shunga Empire

Pataliputra served as the capital of the Shunga Empire Pataliputra served as the capital of the Gupta Empire

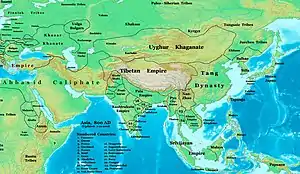

Pataliputra served as the capital of the Gupta Empire Pataliputra served as the capital of the Pala Empire

Pataliputra served as the capital of the Pala Empire

Main recovered artifacts

The Masarh lion, 3rd century BCE

The Masarh lion, 3rd century BCE

Portion of pillar, found in Pataliputra.

Portion of pillar, found in Pataliputra. Pataliputra griffin statuette.

Pataliputra griffin statuette. Winged griffin.

Winged griffin. Pataliputra Yakshas, with Mauryan inscriptions.

Pataliputra Yakshas, with Mauryan inscriptions. Kumrahar coping stone with vines.

Kumrahar coping stone with vines. Pataliputra lotus motifs.

Pataliputra lotus motifs. Polished pillar from Pataliputra.

Polished pillar from Pataliputra. Mason marks at the base of a pillar.[45]

Mason marks at the base of a pillar.[45] Charriot wheel, Bulandi Bagh, Mauryan period.

Charriot wheel, Bulandi Bagh, Mauryan period. Bulandi Bagh female statuette, Sunga period.

Bulandi Bagh female statuette, Sunga period. Buddhist railing, Sunga period.

Buddhist railing, Sunga period.

See also

References

- "Unravelling Pataliputra". The Times of India. 23 April 2023.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004), A History of India, 4th edition. Routledge, Pp. xii, 448, ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- "It took 40 yrs to find first traces of Ashoka's Pataliputra. Now, we must find the rest". 18 September 2023.

- Schwanbeck, E.A. (4 October 2008). Ancient India as described by Megasthenes and Arrian (First published 1657) (23 ed.). Bibliolife.

- Discovery Of The Exact Site Of Asoka's Classic Capital, 1892

- "Patna". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 13 Dec. 2013 <"Patna | India". Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.>.

- "Heritage wall for Metro corridor plan". Archived from the original on 22 November 2016.

- "A relic of Mauryan era". The Times of India. 12 June 2012. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017.

- Valerie Hansen Voyages in World History, Volume 1 to 1600, 2e, Volume 1 pp. 69 Cengage Learning, 2012

- "Pāṭali". A Sanskrit English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged (16th Reprint ed.). New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House. 2011. p. 615. ISBN 978-8120831056.

- Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, p.677

- Folklore, Vol. 19, No. 3 (30 September 1908), pp. 349–350 Archived 10 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- "Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta (DN 16), translated from the Pali by Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu". Dīgha Nikāya of the Pali Canon. dhammatalks.org. 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- Journal of Francis Buchanan (1812), p.182

- Language, Vol. 4, No. 2 (June , 1928), pp. 101–105 Archived 10 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Sujato, Bhikkhu; Bhikkhu, Brahmali, "1.1.5", The Authenticity of the Early Buddhist Texts (PDF), Oxford Center for Buddhist Studies, archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2017.

- Tripathi, Piyush Kumar (16 July 2015). "Realty to broaden horizon". The Telegraph. Calcutta. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015.

- DIODORUS SICULUS -LIBRARY OF HISTORY-Book II, 60

- Sastri 1988, p. 11.

- Thapar, Romilak (1990), A History of India, Volume 1, New Delhi and London: Penguin Books. Pp. 384, ISBN 978-0-14-013835-1.

- The Pearson Indian History Manual, Pearson Education India, A94.

- Lwin, Phyu Mar (2018). "The Buddhist Councils: The Movement to Great Schism". The Journal of International Association of Buddhist Universities (JIABU). 11 (2): 303–314. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- Kowmareeshwari (Ed.), S. (August 2012). Agananuru, Purananuru. Sanga Ilakkiyam (in Tamil). Vol. 3 (1 ed.). Chennai: Saradha Pathippagam. p. 251.

- The Song of Songs and Ancient Tamil Love Poems: Poetry and Symbolism By Abraham Mariaselvam

- Akanaṉūṟu Verses 261 and 265

- Preston, Christine (2009). The Rise of Man in the Gardens of Sumeria: A Biography of L.A. Waddell. Sussex Academic Press. p. 49. ISBN 9781845193157.

- Schlingloff, Dieter (2014). Fortified Cities of Ancient India: A Comparative Study. Anthem Press. p. 49. ISBN 9781783083497.

- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenês and Arrian. Thacker, Spink. 1877. p. 139.

- Arrian, "The Indica" Archived 25 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Kosmin 2014, p. 42.

- Strabo Geographia Vol 3 Paragraph 36 Archived 16 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Aelian, Characteristics of animals, book XIII, Chapter 18, also quoted in The Cambridge History of India, Volume 1, p411

- Asoka Mookerji Radhakumud. Motilal Banarsidass Publishing. 1995. p. 96. ISBN 9788120805828.

- Bhalla, A. S. (2015). Monuments, Power and Poverty in India: From Ashoka to the Raj. I.B.Tauris. p. 18. ISBN 9781784530877.

- "The Analysis of Indian Muria Empire affected from Achaemenid's architecture art". Journal of Subcontinent Researches. 6 (19): 149–174. 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015). The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 414. ISBN 9780521846974.

- Waddell, L. A. (Laurence Austine) (1903). "Report on the excavations at Pātaliputra (Patna); the Palibothra of the Greeks". Calcutta, Bengal secretariat press.

- Beal, Samuel (1884). Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World. London: Trubner & Co.

- Beal, Samuel (1884). Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Altekar, A. S.; Mishra, Vijayakanta (1959). Report on Kumrahar Excavations: 1951-1955. Patna: K. P. Jayaswal Research Institute. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- Singh, Rajeshwar Prasad (1975). "The Decline of Pātaliputra with Special Reference to Geographic Factors". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 36: 51–62. JSTOR 44138834. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- Sinha, B. P.; Narain, Lala Aditya (1970). Pāṭaliputra Excavation, 1955-56. Patna: Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Bihar. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- Delle cose maravigliose del mondo Tradotto da Giovan Vincenzo Belprato, Count of Antwerp, by Caius Julius Solinus (Solino), 1559, page 209.

- Excavation sites in Bihar, Archaeological Survey of India, archived from the original on 28 October 2009, retrieved 13 September 2009.

- Foreign Influence on Ancient India, de Krishna Chandra Sagar p.41

Sources

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta, ed. (1988) [1967], Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0465-4

Further reading

- Bernstein, Richard (2001). Ultimate Journey: Retracing the Path of an Ancient Buddhist Monk (Xuanzang) who crossed Asia in Search of Enlightenment. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. ISBN 0-375-40009-5

External links