Programme for International Student Assessment

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a worldwide study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in member and non-member nations intended to evaluate educational systems by measuring 15-year-old school pupils' scholastic performance on mathematics, science, and reading.[1] It was first performed in 2000 and then repeated every three years. Its aim is to provide comparable data with a view to enabling countries to improve their education policies and outcomes. It measures problem solving and cognition.[2]

| Abbreviation | PISA |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1997 |

| Purpose | Comparison of education attainment across the world |

| Headquarters | OECD Headquarters |

| Location |

|

Region served | World |

Membership | 79 government education departments |

Official language | English and French |

Head of the Early Childhood and Schools Division | Yuri Belfali |

Main organ | PISA Governing Body (Chair – Michele Bruniges) |

Parent organization | OECD |

| Website | www |

The results of the 2018 data collection were released on 3 December 2019.[3]

Influence and impact

PISA, and similar international standardised assessments of educational attainment are increasingly used in the process of education policymaking at both national and international levels.[4]

PISA was conceived to set in a wider context the information provided by national monitoring of education system performance through regular assessments within a common, internationally agreed framework; by investigating relationships between student learning and other factors they can "offer insights into sources of variation in performances within and between countries".[5]

Until the 1990s, few European countries used national tests. In the 1990s, ten countries / regions introduced standardised assessment, and since the early 2000s, ten more followed suit. By 2009, only five European education systems had no national student assessments.[4]

The impact of these international standardised assessments in the field of educational policy has been significant, in terms of the creation of new knowledge, changes in assessment policy, and external influence over national educational policy more broadly.

Creation of new knowledge

Data from international standardised assessments can be useful in research on causal factors within or across education systems.[4] Mons notes that the databases generated by large-scale international assessments have made it possible to carry out inventories and comparisons of education systems on an unprecedented scale* on themes ranging from the conditions for learning mathematics and reading, to institutional autonomy and admissions policies.[6] They allow typologies to be developed that can be used for comparative statistical analyses of education performance indicators, thereby identifying the consequences of different policy choices. They have generated new knowledge about education: PISA findings have challenged deeply embedded educational practices, such as the early tracking of students into vocational or academic pathways.[7]

- 79 countries and economies participated in the 2018 data collection.

Barroso and de Carvalho find that PISA provides a common reference connecting academic research in education and the political realm of public policy, operating as a mediator between different strands of knowledge from the realm of education and public policy.[8] However, although the key findings from comparative assessments are widely shared in the research community[4] the knowledge they create does not necessarily fit with government reform agendas; this leads to some inappropriate uses of assessment data.

Changes in national assessment policy

Emerging research suggests that international standardised assessments are having an impact on national assessment policy and practice. PISA is being integrated into national policies and practices on assessment, evaluation, curriculum standards and performance targets; its assessment frameworks and instruments are being used as best-practice models for improving national assessments; many countries have explicitly incorporated and emphasise PISA-like competencies in revised national standards and curricula; others use PISA data to complement national data and validate national results against an international benchmark.[7]

External influence over national educational policy

More important than its influence on countries' policy of student assessment, is the range of ways in which PISA is influencing countries education policy choices.

Policy-makers in most participating countries see PISA as an important indicator of system performance; PISA reports can define policy problems and set the agenda for national policy debate; policymakers seem to accept PISA as a valid and reliable instrument for internationally benchmarking system performance and changes over time; most countries—irrespective of whether they performed above, at, or below the average PISA score—have begun policy reforms in response to PISA reports.[7]

Against this, impact on national education systems varies markedly. For example, in Germany, the results of the first PISA assessment caused the so-called 'PISA shock': a questioning of previously accepted educational policies; in a state marked by jealously guarded regional policy differences, it led ultimately to an agreement by all Länder to introduce common national standards and even an institutionalised structure to ensure that they were observed.[9] In Hungary, by comparison, which shared similar conditions to Germany, PISA results have not led to significant changes in educational policy.[10]

Because many countries have set national performance targets based on their relative rank or absolute PISA score, PISA assessments have increased the influence of their (non-elected) commissioning body, the OECD, as an international education monitor and policy actor, which implies an important degree of 'policy transfer' from the international to the national level; PISA in particular is having "an influential normative effect on the direction of national education policies".[7] Thus, it is argued that the use of international standardised assessments has led to a shift towards international, external accountability for national system performance; Rey contends that PISA surveys, portrayed as objective, third-party diagnoses of education systems, actually serve to promote specific orientations on educational issues.[4]

National policy actors refer to high-performing PISA countries to "help legitimise and justify their intended reform agenda within contested national policy debates".[11] PISA data can be "used to fuel long-standing debates around pre-existing conflicts or rivalries between different policy options, such as in the French Community of Belgium".[12] In such instances, PISA assessment data are used selectively: in public discourse governments often only use superficial features of PISA surveys such as country rankings and not the more detailed analyses. Rey (2010:145, citing Greger, 2008) notes that often the real results of PISA assessments are ignored as policymakers selectively refer to data in order to legitimise policies introduced for other reasons.[13]

In addition, PISA's international comparisons can be used to justify reforms with which the data themselves have no connection; in Portugal, for example, PISA data were used to justify new arrangements for teacher assessment (based on inferences that were not justified by the assessments and data themselves); they also fed the government's discourse about the issue of pupils repeating a year, (which, according to research, fails to improve student results).[14] In Finland, the country's PISA results (that are in other countries deemed to be excellent) were used by Ministers to promote new policies for 'gifted' students.[15] Such uses and interpretations often assume causal relationships that cannot legitimately be based upon PISA data which would normally require fuller investigation through qualitative in-depth studies and longitudinal surveys based on mixed quantitative and qualitative methods,[16] which politicians are often reluctant to fund.

Recent decades have witnessed an expansion in the uses of PISA and similar assessments, from assessing students' learning, to connecting "the educational realm (their traditional remit) with the political realm".[17] This raises the question of whether PISA data are sufficiently robust to bear the weight of the major policy decisions that are being based upon them, for, according to Breakspear, PISA data have "come to increasingly shape, define and evaluate the key goals of the national / federal education system".[7] This implies that those who set the PISA tests – e.g. in choosing the content to be assessed and not assessed – are in a position of considerable power to set the terms of the education debate, and to orient educational reform in many countries around the globe.[7]

Framework

PISA stands in a tradition of international school studies, undertaken since the late 1950s by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). Much of PISA's methodology follows the example of the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS, started in 1995), which in turn was much influenced by the U.S. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). The reading component of PISA is inspired by the IEA's Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS).

PISA aims to test literacy the competence of students in three fields: reading, mathematics, science on an indefinite scale.[18]

The PISA mathematics literacy test asks students to apply their mathematical knowledge to solve problems set in real-world contexts. To solve the problems students must activate a number of mathematical competencies as well as a broad range of mathematical content knowledge. TIMSS, on the other hand, measures more traditional classroom content such as an understanding of fractions and decimals and the relationship between them (curriculum attainment). PISA claims to measure education's application to real-life problems and lifelong learning (workforce knowledge).

In the reading test, "OECD/PISA does not measure the extent to which 15-year-old students are fluent readers or how competent they are at word recognition tasks or spelling." Instead, they should be able to "construct, extend and reflect on the meaning of what they have read across a wide range of continuous and non-continuous texts."[19]

PISA also assesses students in innovative domains. In 2012 and 2015 in addition to reading, mathematics and science, they were tested in collaborative problem solving. In 2018 the additional innovative domain was global competence.

Implementation

PISA is sponsored, governed, and coordinated by the OECD, but paid for by participating countries.

Method of testing

Sampling

The students tested by PISA are aged between 15 years and 3 months and 16 years and 2 months at the beginning of the assessment period. The school year pupils are in is not taken into consideration. Only students at school are tested, not home-schoolers. In PISA 2006, however, several countries also used a grade-based sample of students. This made it possible to study how age and school year interact.

To fulfill OECD requirements, each country must draw a sample of at least 5,000 students. In small countries like Iceland and Luxembourg, where there are fewer than 5,000 students per year, an entire age cohort is tested. Some countries used much larger samples than required to allow comparisons between regions.

Test

Each student takes a two-hour computer based test. Part of the test is multiple-choice and part involves fuller answers. There are six and a half hours of assessment material, but each student is not tested on all the parts. Following the cognitive test, participating students spend nearly one more hour answering a questionnaire on their background including learning habits, motivation, and family. School directors fill in a questionnaire describing school demographics, funding, etc. In 2012 the participants were, for the first time in the history of large-scale testing and assessments, offered a new type of problem, i.e. interactive (complex) problems requiring exploration of a novel virtual device.[20][21]

In selected countries, PISA started experimentation with computer adaptive testing.

National add-ons

Countries are allowed to combine PISA with complementary national tests.

Germany does this in a very extensive way: On the day following the international test, students take a national test called PISA-E (E=Ergänzung=complement). Test items of PISA-E are closer to TIMSS than to PISA. While only about 5,000 German students participate in the international and the national test, another 45,000 take the national test only. This large sample is needed to allow an analysis by federal states. Following a clash about the interpretation of 2006 results, the OECD warned Germany that it might withdraw the right to use the "PISA" label for national tests.[22]

Data scaling

From the beginning, PISA has been designed with one particular method of data analysis in mind. Since students work on different test booklets, raw scores must be 'scaled' to allow meaningful comparisons. Scores are thus scaled so that the OECD average in each domain (mathematics, reading and science) is 500 and the standard deviation is 100.[23] This is true only for the initial PISA cycle when the scale was first introduced, though, subsequent cycles are linked to the previous cycles through IRT scale linking methods.[24]

This generation of proficiency estimates is done using a latent regression extension of the Rasch model, a model of item response theory (IRT), also known as conditioning model or population model. The proficiency estimates are provided in the form of so-called plausible values, which allow unbiased estimates of differences between groups. The latent regression, together with the use of a Gaussian prior probability distribution of student competencies allows estimation of the proficiency distributions of groups of participating students.[25] The scaling and conditioning procedures are described in nearly identical terms in the Technical Reports of PISA 2000, 2003, 2006. NAEP and TIMSS use similar scaling methods.

Ranking results

All PISA results are tabulated by country; recent PISA cycles have separate provincial or regional results for some countries. Most public attention concentrates on just one outcome: the mean scores of countries and their rankings of countries against one another. In the official reports, however, country-by-country rankings are given not as simple league tables but as cross tables indicating for each pair of countries whether or not mean score differences are statistically significant (unlikely to be due to random fluctuations in student sampling or in item functioning). In favorable cases, a difference of 9 points is sufficient to be considered significant.

PISA never combines mathematics, science and reading domain scores into an overall score. However, commentators have sometimes combined test results from all three domains into an overall country ranking. Such meta-analysis is not endorsed by the OECD, although official summaries sometimes use scores from a testing cycle's principal domain as a proxy for overall student ability.

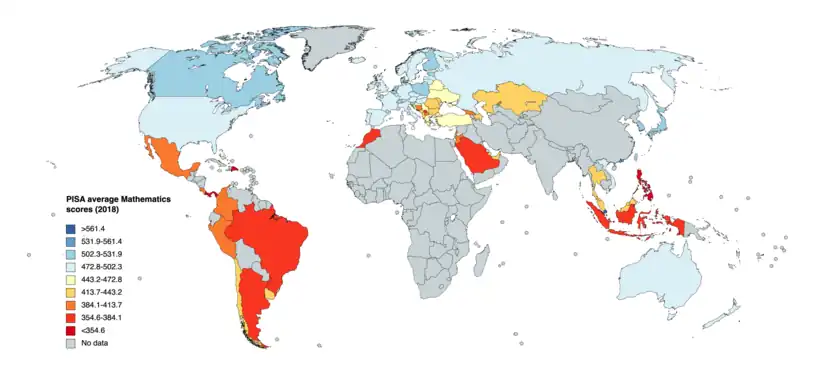

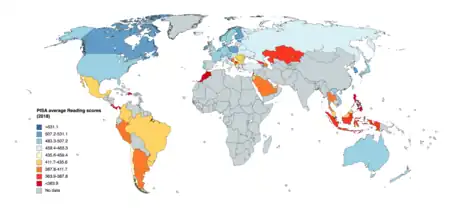

PISA 2018 ranking summary

The results of PISA 2018 were presented on 3 December 2019, which included data for around 600,000 participating students in 79 countries and economies, with China's economic area of Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang emerging as the top performer in all categories.[26] Note that this does not represent the entirety of mainland China.[27] Reading results for Spain were not released due to perceived anomalies.[28]

| Mathematics | Science | Reading | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Rankings comparison 2000–2015

| Mathematics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | 2003 | 2000 | ||||||

| Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | |

| International Average (OECD) | 490 | — | 494 | — | 495 | — | 494 | — | 499 | — | 492 | — |

| 413 | 57 | 394 | 54 | 377 | 53 | — | — | — | — | 381 | 33 | |

| 360 | 72 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 409 | 58 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 388 | 30 | |

| 494 | 25 | 504 | 17 | 514 | 13 | 520 | 12 | 524 | 10 | 533 | 6 | |

| 497 | 20 | 506 | 16 | 496 | 22 | 505 | 17 | 506 | 18 | 503 | 12 | |

| 531 | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 507 | 15 | 515 | 13 | 515 | 12 | 520 | 11 | 529 | 7 | 520 | 8 | |

| 377 | 68 | 389 | 55 | 386 | 51 | 370 | 50 | 356 | 39 | 334 | 35 | |

| 441 | 47 | 439 | 43 | 428 | 41 | 413 | 43 | — | — | 430 | 28 | |

| 456 | 43 | 418 | 49 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 516 | 10 | 518 | 11 | 527 | 8 | 527 | 7 | 532 | 6 | 533 | 6 | |

| 423 | 50 | 423 | 47 | 421 | 44 | 411 | 44 | — | — | 384 | 32 | |

| 542 | 4 | 560 | 3 | 543 | 4 | 549 | 1 | — | — | — | — | |

| 390 | 64 | 376 | 58 | 381 | 52 | 370 | 49 | — | — | — | — | |

| 400 | 62 | 407 | 53 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 464 | 41 | 471 | 38 | 460 | 38 | 467 | 34 | — | — | — | — | |

| 437 | 48 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 492 | 28 | 499 | 22 | 493 | 25 | 510 | 15 | 516 | 12 | 498 | 14 | |

| 511 | 12 | 500 | 20 | 503 | 17 | 513 | 14 | 514 | 14 | 514 | 10 | |

| 328 | 73 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 520 | 9 | 521 | 9 | 512 | 15 | 515 | 13 | — | — | — | — | |

| 511 | 13 | 519 | 10 | 541 | 5 | 548 | 2 | 544 | 2 | 536 | 5 | |

| 493 | 26 | 495 | 23 | 497 | 20 | 496 | 22 | 511 | 15 | 517 | 9 | |

| 371 | 69 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 381 | 33 | |

| 404 | 60 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 506 | 16 | 514 | 14 | 513 | 14 | 504 | 19 | 503 | 19 | 490 | 16 | |

| 454 | 44 | 453 | 40 | 466 | 37 | 459 | 37 | 445 | 32 | 447 | 24 | |

| 548 | 2 | 561 | 2 | 555 | 2 | 547 | 3 | 550 | 1 | 560 | 1 | |

| 477 | 37 | 477 | 37 | 490 | 27 | 491 | 26 | 490 | 25 | 488 | 17 | |

| 488 | 31 | 493 | 25 | 507 | 16 | 506 | 16 | 515 | 13 | 514 | 10 | |

| 386 | 66 | 375 | 60 | 371 | 55 | 391 | 47 | 360 | 37 | 367 | 34 | |

| 504 | 18 | 501 | 18 | 487 | 30 | 501 | 21 | 503 | 20 | 503 | 12 | |

| 470 | 39 | 466 | 39 | 447 | 39 | 442 | 38 | — | — | 433 | 26 | |

| 490 | 30 | 485 | 30 | 483 | 33 | 462 | 36 | 466 | 31 | 457 | 22 | |

| 532 | 5 | 536 | 6 | 529 | 7 | 523 | 9 | 534 | 5 | 557 | 2 | |

| 380 | 67 | 386 | 57 | 387 | 50 | 384 | 48 | — | — | — | — | |

| 460 | 42 | 432 | 45 | 405 | 48 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 524 | 7 | 554 | 4 | 546 | 3 | 547 | 4 | 542 | 3 | 547 | 3 | |

| 362 | 71 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 482 | 34 | 491 | 26 | 482 | 34 | 486 | 30 | 483 | 27 | 463 | 21 | |

| 396 | 63 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 478 | 36 | 479 | 35 | 477 | 35 | 486 | 29 | — | — | — | — | |

| 486 | 33 | 490 | 27 | 489 | 28 | 490 | 27 | 493 | 23 | 446 | 25 | |

| 544 | 3 | 538 | 5 | 525 | 10 | 525 | 8 | 527 | 8 | — | — | |

| 446 | 45 | 421 | 48 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 479 | 35 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 408 | 59 | 413 | 50 | 419 | 46 | 406 | 45 | 385 | 36 | 387 | 31 | |

| 420 | 52 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 418 | 54 | 410 | 51 | 403 | 49 | 399 | 46 | — | — | — | — | |

| 512 | 11 | 523 | 8 | 526 | 9 | 531 | 5 | 538 | 4 | — | — | |

| 495 | 21 | 500 | 21 | 519 | 11 | 522 | 10 | 523 | 11 | 537 | 4 | |

| 502 | 19 | 489 | 28 | 498 | 19 | 490 | 28 | 495 | 22 | 499 | 13 | |

| 387 | 65 | 368 | 61 | 365 | 57 | — | — | — | — | 292 | 36 | |

| 504 | 17 | 518 | 12 | 495 | 23 | 495 | 24 | 490 | 24 | 470 | 20 | |

| 492 | 29 | 487 | 29 | 487 | 31 | 466 | 35 | 466 | 30 | 454 | 23 | |

| 402 | 61 | 376 | 59 | 368 | 56 | 318 | 52 | — | — | — | — | |

| 444 | 46 | 445 | 42 | 427 | 42 | 415 | 42 | — | — | 426 | 29 | |

| 494 | 23 | 482 | 32 | 468 | 36 | 476 | 32 | 468 | 29 | 478 | 18 | |

| 564 | 1 | 573 | 1 | 562 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 475 | 38 | 482 | 33 | 497 | 21 | 492 | 25 | 498 | 21 | — | — | |

| 510 | 14 | 501 | 19 | 501 | 18 | 504 | 18 | — | — | — | — | |

| 486 | 32 | 484 | 31 | 483 | 32 | 480 | 31 | 485 | 26 | 476 | 19 | |

| 494 | 24 | 478 | 36 | 494 | 24 | 502 | 20 | 509 | 16 | 510 | 11 | |

| 521 | 8 | 531 | 7 | 534 | 6 | 530 | 6 | 527 | 9 | 529 | 7 | |

| 415 | 56 | 427 | 46 | 419 | 45 | 417 | 41 | 417 | 35 | 432 | 27 | |

| 417 | 55 | — | — | 414 | 47 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 367 | 70 | 388 | 56 | 371 | 54 | 365 | 51 | 359 | 38 | — | — | |

| 420 | 51 | 448 | 41 | 445 | 40 | 424 | 40 | 423 | 33 | — | — | |

| 427 | 49 | 434 | 44 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 492 | 27 | 494 | 24 | 492 | 26 | 495 | 23 | 508 | 17 | 529 | 7 | |

| 470 | 40 | 481 | 34 | 487 | 29 | 474 | 33 | 483 | 28 | 493 | 15 | |

| 418 | 53 | 409 | 52 | 427 | 43 | 427 | 39 | 422 | 34 | — | — | |

| 495 | 22 | 511 | 15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Science | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | ||||

| Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | |

| International Average (OECD) | 493 | — | 501 | — | 501 | — | 498 | — |

| 427 | 54 | 397 | 58 | 391 | 54 | — | — | |

| 376 | 72 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 432 | 52 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 510 | 14 | 521 | 14 | 527 | 9 | 527 | 8 | |

| 495 | 26 | 506 | 21 | 494 | 28 | 511 | 17 | |

| 518 | 10 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 502 | 20 | 505 | 22 | 507 | 19 | 510 | 18 | |

| 401 | 66 | 402 | 55 | 405 | 49 | 390 | 49 | |

| 446 | 46 | 446 | 43 | 439 | 42 | 434 | 40 | |

| 475 | 38 | 425 | 49 | — | — | — | — | |

| 528 | 7 | 525 | 9 | 529 | 7 | 534 | 3 | |

| 447 | 45 | 445 | 44 | 447 | 41 | 438 | 39 | |

| 532 | 4 | 523 | 11 | 520 | 11 | 532 | 4 | |

| 416 | 60 | 399 | 56 | 402 | 50 | 388 | 50 | |

| 420 | 58 | 429 | 47 | — | — | — | — | |

| 475 | 37 | 491 | 32 | 486 | 35 | 493 | 25 | |

| 433 | 51 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 493 | 29 | 508 | 20 | 500 | 22 | 513 | 14 | |

| 502 | 21 | 498 | 25 | 499 | 24 | 496 | 23 | |

| 332 | 73 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 534 | 3 | 541 | 5 | 528 | 8 | 531 | 5 | |

| 531 | 5 | 545 | 4 | 554 | 1 | 563 | 1 | |

| 495 | 27 | 499 | 24 | 498 | 25 | 495 | 24 | |

| 384 | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 411 | 63 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 509 | 16 | 524 | 10 | 520 | 12 | 516 | 12 | |

| 455 | 44 | 467 | 40 | 470 | 38 | 473 | 37 | |

| 523 | 9 | 555 | 1 | 549 | 2 | 542 | 2 | |

| 477 | 35 | 494 | 30 | 503 | 20 | 504 | 20 | |

| 473 | 39 | 478 | 37 | 496 | 26 | 491 | 26 | |

| 403 | 65 | 382 | 60 | 383 | 55 | 393 | 48 | |

| 503 | 19 | 522 | 13 | 508 | 18 | 508 | 19 | |

| 467 | 40 | 470 | 39 | 455 | 39 | 454 | 38 | |

| 481 | 34 | 494 | 31 | 489 | 33 | 475 | 35 | |

| 538 | 2 | 547 | 3 | 539 | 4 | 531 | 6 | |

| 409 | 64 | 409 | 54 | 415 | 47 | 422 | 43 | |

| 456 | 43 | 425 | 48 | 400 | 53 | — | — | |

| 516 | 11 | 538 | 6 | 538 | 5 | 522 | 10 | |

| 378 | 71 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 490 | 31 | 502 | 23 | 494 | 29 | 490 | 27 | |

| 386 | 68 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 475 | 36 | 496 | 28 | 491 | 31 | 488 | 31 | |

| 483 | 33 | 491 | 33 | 484 | 36 | 486 | 33 | |

| 529 | 6 | 521 | 15 | 511 | 16 | 511 | 16 | |

| 443 | 47 | 420 | 50 | — | — | — | — | |

| 465 | 41 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 416 | 61 | 415 | 52 | 416 | 46 | 410 | 47 | |

| 428 | 53 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 411 | 62 | 410 | 53 | 401 | 51 | 412 | 46 | |

| 509 | 17 | 522 | 12 | 522 | 10 | 525 | 9 | |

| 513 | 12 | 516 | 16 | 532 | 6 | 530 | 7 | |

| 498 | 24 | 495 | 29 | 500 | 23 | 487 | 32 | |

| 397 | 67 | 373 | 61 | 369 | 57 | — | — | |

| 501 | 22 | 526 | 8 | 508 | 17 | 498 | 22 | |

| 501 | 23 | 489 | 34 | 493 | 30 | 474 | 36 | |

| 418 | 59 | 384 | 59 | 379 | 56 | 349 | 52 | |

| 435 | 50 | 439 | 46 | 428 | 43 | 418 | 45 | |

| 487 | 32 | 486 | 35 | 478 | 37 | 479 | 34 | |

| 556 | 1 | 551 | 2 | 542 | 3 | — | — | |

| 461 | 42 | 471 | 38 | 490 | 32 | 488 | 29 | |

| 513 | 13 | 514 | 18 | 512 | 15 | 519 | 11 | |

| 493 | 30 | 496 | 27 | 488 | 34 | 488 | 30 | |

| 493 | 28 | 485 | 36 | 495 | 27 | 503 | 21 | |

| 506 | 18 | 515 | 17 | 517 | 13 | 512 | 15 | |

| 421 | 57 | 444 | 45 | 425 | 45 | 421 | 44 | |

| 425 | 56 | — | — | 410 | 48 | — | — | |

| 386 | 69 | 398 | 57 | 401 | 52 | 386 | 51 | |

| 425 | 55 | 463 | 41 | 454 | 40 | 424 | 42 | |

| 437 | 48 | 448 | 42 | — | — | — | — | |

| 509 | 15 | 514 | 19 | 514 | 14 | 515 | 13 | |

| 496 | 25 | 497 | 26 | 502 | 21 | 489 | 28 | |

| 435 | 49 | 416 | 51 | 427 | 44 | 428 | 41 | |

| 525 | 8 | 528 | 7 | — | — | — | — | |

| Reading | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | 2003 | 2000 | ||||||

| Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | |

| International Average (OECD) | 493 | — | 496 | — | 493 | — | 489 | — | 494 | — | 493 | — |

| 405 | 63 | 394 | 58 | 385 | 55 | — | — | — | — | 349 | 39 | |

| 350 | 71 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 425 | 56 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 503 | 16 | 512 | 12 | 515 | 8 | 513 | 7 | 525 | 4 | 528 | 4 | |

| 485 | 33 | 490 | 26 | 470 | 37 | 490 | 21 | 491 | 22 | 492 | 19 | |

| 494 | 27 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 499 | 20 | 509 | 16 | 506 | 10 | 501 | 11 | 507 | 11 | 507 | 11 | |

| 407 | 62 | 407 | 52 | 412 | 49 | 393 | 47 | 403 | 36 | 396 | 36 | |

| 432 | 49 | 436 | 47 | 429 | 42 | 402 | 43 | — | — | 430 | 32 | |

| 475 | 38 | 429 | 48 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 527 | 3 | 523 | 7 | 524 | 5 | 527 | 4 | 528 | 3 | 534 | 2 | |

| 459 | 42 | 441 | 43 | 449 | 41 | 442 | 37 | — | — | 410 | 35 | |

| 497 | 23 | 523 | 8 | 495 | 21 | 496 | 15 | — | — | — | — | |

| 425 | 57 | 403 | 54 | 413 | 48 | 385 | 49 | — | — | — | — | |

| 427 | 52 | 441 | 45 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 487 | 31 | 485 | 33 | 476 | 34 | 477 | 29 | — | — | — | — | |

| 443 | 45 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 487 | 30 | 493 | 24 | 478 | 32 | 483 | 25 | 489 | 24 | 492 | 20 | |

| 500 | 18 | 496 | 23 | 495 | 22 | 494 | 18 | 492 | 19 | 497 | 16 | |

| 358 | 69 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 519 | 6 | 516 | 10 | 501 | 12 | 501 | 12 | — | — | — | — | |

| 526 | 4 | 524 | 5 | 536 | 2 | 547 | 2 | 543 | 1 | 546 | 1 | |

| 499 | 19 | 505 | 19 | 496 | 20 | 488 | 22 | 496 | 17 | 505 | 14 | |

| 352 | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 373 | 37 | |

| 401 | 65 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 509 | 11 | 508 | 18 | 497 | 18 | 495 | 17 | 491 | 21 | 484 | 22 | |

| 467 | 41 | 477 | 38 | 483 | 30 | 460 | 35 | 472 | 30 | 474 | 25 | |

| 527 | 2 | 545 | 1 | 533 | 3 | 536 | 3 | 510 | 9 | 525 | 6 | |

| 470 | 40 | 488 | 28 | 494 | 24 | 482 | 26 | 482 | 25 | 480 | 23 | |

| 482 | 35 | 483 | 35 | 500 | 15 | 484 | 23 | 492 | 20 | 507 | 12 | |

| 397 | 67 | 396 | 57 | 402 | 53 | 393 | 46 | 382 | 38 | 371 | 38 | |

| 521 | 5 | 523 | 6 | 496 | 19 | 517 | 6 | 515 | 6 | 527 | 5 | |

| 479 | 37 | 486 | 32 | 474 | 35 | 439 | 39 | — | — | 452 | 29 | |

| 485 | 34 | 490 | 25 | 486 | 27 | 469 | 32 | 476 | 29 | 487 | 21 | |

| 516 | 8 | 538 | 3 | 520 | 7 | 498 | 14 | 498 | 14 | 522 | 9 | |

| 408 | 61 | 399 | 55 | 405 | 51 | 401 | 44 | — | — | — | — | |

| 427 | 54 | 393 | 59 | 390 | 54 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 517 | 7 | 536 | 4 | 539 | 1 | 556 | 1 | 534 | 2 | 525 | 7 | |

| 347 | 72 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 488 | 29 | 489 | 27 | 484 | 28 | 479 | 27 | 491 | 23 | 458 | 28 | |

| 347 | 73 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 472 | 39 | 477 | 37 | 468 | 38 | 470 | 31 | — | — | — | — | |

| 481 | 36 | 488 | 30 | 472 | 36 | 479 | 28 | 479 | 27 | 441 | 30 | |

| 509 | 12 | 509 | 15 | 487 | 26 | 492 | 20 | 498 | 15 | — | — | |

| 431 | 50 | 398 | 56 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 447 | 44 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 423 | 58 | 424 | 49 | 425 | 44 | 410 | 42 | 400 | 37 | 422 | 34 | |

| 416 | 59 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 427 | 55 | 422 | 50 | 408 | 50 | 392 | 48 | — | — | — | — | |

| 503 | 15 | 511 | 13 | 508 | 9 | 507 | 10 | 513 | 8 | ‡ | ‡ | |

| 509 | 10 | 512 | 11 | 521 | 6 | 521 | 5 | 522 | 5 | 529 | 3 | |

| 513 | 9 | 504 | 20 | 503 | 11 | 484 | 24 | 500 | 12 | 505 | 13 | |

| 398 | 66 | 384 | 61 | 370 | 57 | — | — | — | — | 327 | 40 | |

| 506 | 13 | 518 | 9 | 500 | 14 | 508 | 8 | 497 | 16 | 479 | 24 | |

| 498 | 21 | 488 | 31 | 489 | 25 | 472 | 30 | 478 | 28 | 470 | 26 | |

| 402 | 64 | 388 | 60 | 372 | 56 | 312 | 51 | — | — | — | — | |

| 434 | 47 | 438 | 46 | 424 | 45 | 396 | 45 | — | — | 428 | 33 | |

| 495 | 26 | 475 | 40 | 459 | 40 | 440 | 38 | 442 | 32 | 462 | 27 | |

| 535 | 1 | 542 | 2 | 526 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 453 | 43 | 463 | 41 | 477 | 33 | 466 | 33 | 469 | 31 | — | — | |

| 505 | 14 | 481 | 36 | 483 | 29 | 494 | 19 | — | — | — | — | |

| 496 | 25 | 488 | 29 | 481 | 31 | 461 | 34 | 481 | 26 | 493 | 18 | |

| 500 | 17 | 483 | 34 | 497 | 17 | 507 | 9 | 514 | 7 | 516 | 10 | |

| 492 | 28 | 509 | 14 | 501 | 13 | 499 | 13 | 499 | 13 | 494 | 17 | |

| 409 | 60 | 441 | 44 | 421 | 46 | 417 | 40 | 420 | 35 | 431 | 31 | |

| 427 | 53 | — | — | 416 | 47 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 361 | 68 | 404 | 53 | 404 | 52 | 380 | 50 | 375 | 39 | — | — | |

| 428 | 51 | 475 | 39 | 464 | 39 | 447 | 36 | 441 | 33 | — | — | |

| 434 | 48 | 442 | 42 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 498 | 22 | 499 | 21 | 494 | 23 | 495 | 16 | 507 | 10 | 523 | 8 | |

| 497 | 24 | 498 | 22 | 500 | 16 | — | — | 495 | 18 | 504 | 15 | |

| 437 | 46 | 411 | 51 | 426 | 43 | 413 | 41 | 434 | 34 | — | — | |

| 487 | 32 | 508 | 17 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

Previous years

| Period | Focus | OECD countries | Partner countries | Participating students | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Reading | 28 | 4 + 11 | 265,000 | The Netherlands disqualified from data analysis. 11 additional non-OECD countries took the test in 2002. |

| 2003 | Mathematics | 30 | 11 | 275,000 | UK disqualified from data analysis. Also included test in problem solving. |

| 2006 | Science | 30 | 27 | 400,000 | Reading scores for US disqualified from analysis due to misprint in testing materials.[29] |

| 2009[30] | Reading | 34 | 41 + 10 | 470,000 | 10 additional non-OECD countries took the test in 2010.[31][32] |

| 2012[33] | Mathematics | 34 | 31 | 510,000 |

Reception

(China) China's participation in the 2012 test was limited to Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Macau as separate entities. In 2012, Shanghai participated for the second time, again topping the rankings in all three subjects, as well as improving scores in the subjects compared to the 2009 tests. Shanghai's score of 613 in mathematics was 113 points above the average score, putting the performance of Shanghai pupils about 3 school years ahead of pupils in average countries. Educational experts debated to what degree this result reflected the quality of the general educational system in China, pointing out that Shanghai has greater wealth and better-paid teachers than the rest of China.[34] Hong Kong placed second in reading and science and third in maths.

Andreas Schleicher, PISA division head and co-ordinator, stated that PISA tests administered in rural China have produced some results approaching the OECD average. Citing further as-yet-unpublished OECD research, he said, "We have actually done Pisa in 12 of the provinces in China. Even in some of the very poor areas you get performance close to the OECD average."[35] Schleicher believes that China has also expanded school access and has moved away from learning by rote,[36] performing well in both rote-based and broader assessments.[35]

In 2018 the Chinese provinces that participated were Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang. In 2015, the participating provinces were Jiangsu, Guangdong, Beijing, and Shanghai.[37] The 2015 Beijing-Shanghai-Jiangsu-Guangdong cohort scored a median 518 in science in 2015, while the 2012 Shanghai cohort scored a median 580.

Critics of PISA counter that in Shanghai and other Chinese cities, most children of migrant workers can only attend city schools up to the ninth grade, and must return to their parents' hometowns for high school due to hukou restrictions, thus skewing the composition of the city's high school students in favor of wealthier local families. A population chart of Shanghai reproduced in The New York Times shows a steep drop off in the number of 15-year-olds residing there.[38] According to Schleicher, 27% of Shanghai's 15-year-olds are excluded from its school system (and hence from testing). As a result, the percentage of Shanghai's 15-year-olds tested by PISA was 73%, lower than the 89% tested in the US.[39] Following the 2015 testing, OECD published in depth studies on the education systems of a selected few countries including China.[40]

In 2014, Liz Truss, the British Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department for Education, led a fact-finding visit to schools and teacher-training centres in Shanghai.[41] Britain increased exchanges with Chinese teachers and schools to find out how to improve quality. In 2014, 60 teachers from Shanghai were invited to the UK to help share their teaching methods, support pupils who are struggling, and help to train other teachers.[42] In 2016, Britain invited 120 Chinese teachers, planning to adopt Chinese styles of teaching in 8,000 aided schools.[43] By 2019, approximately 5,000 of Britain's 16,000 primary schools had adopted the Shanghai's teaching methods.[44] The performance of British schools in PISA improved after adopting China's teaching styles.[45][46]

Finland

Finland, which received several top positions in the first tests, fell in all three subjects in 2012, but remained the best performing country overall in Europe, achieving their best result in science with 545 points (5th) and worst in mathematics with 519 (12th) in which the country was outperformed by four other European countries. The drop in mathematics was 25 points since 2003, the last time mathematics was the focus of the tests. For the first time Finnish girls outperformed boys in mathematics narrowly. It was also the first time pupils in Finnish-speaking schools did not perform better than pupils in Swedish-speaking schools. Minister of Education and Science Krista Kiuru expressed concern for the overall drop, as well as the fact that the number of low-performers had increased from 7% to 12%.[47]

India

India participated in the 2009 round of testing but pulled out of the 2012 PISA testing, with the Indian government attributing its action to the unfairness of PISA testing to Indian students.[48] India had ranked 72nd out of 73 countries tested in 2009.[49] The Indian Express reported, "The ministry (of education) has concluded that there was a socio-cultural disconnect between the questions and Indian students. The ministry will write to the OECD and drive home the need to factor in India's "socio-cultural milieu". India's participation in the next PISA cycle will hinge on this".[50] The Indian Express also noted that "Considering that over 70 nations participate in PISA, it is uncertain whether an exception would be made for India".

India did not participate in the 2012, 2015 and 2018 PISA rounds.[51]

A Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan (KVS) committee as well as a group of secretaries on education constituted by the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi recommended that India should participate in PISA. Accordingly, in February 2017, the Ministry of Human Resource Development under Prakash Javadekar decided to end the boycott and participate in PISA from 2020. To address the socio-cultural disconnect between the test questions and students, it was reported that the OECD will update some questions. For example, the word avocado in a question may be replaced with a more popular Indian fruit such as mango.[52]

Malaysia

In 2015, the results from Malaysia were found by the OECD to have not met the maximum response rate.[53] Opposition politician Ong Kian Ming said the education ministry tried to oversample high-performing students in rich schools.[54][55]

Sweden

Sweden's result dropped in all three subjects in the 2012 test, which was a continuation of a trend from 2006 and 2009. It saw the sharpest fall in mathematics performance with a drop in score from 509 in 2003 to 478 in 2012. The score in reading showed a drop from 516 in 2000 to 483 in 2012. The country performed below the OECD average in all three subjects.[56] The leader of the opposition, Social Democrat Stefan Löfven, described the situation as a national crisis.[57] Along with the party's spokesperson on education, Ibrahim Baylan, he pointed to the downward trend in reading as most severe.[57]

In 2020, Swedish newspaper Expressen revealed that Sweden had inflated their score in PISA 2018 by not conforming to OECD standards. According to professor Magnus Henrekson a large number of foreign-born students had not been tested.[58] According to an article of Sveriges Radio, poor immigrant children's scores are a significant cause of the recent decrease in Swedish Pisa scores.

United Kingdom

In the 2012 test, as in 2009, the result was slightly above average for the United Kingdom, with the science ranking being highest (20).[59] England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland also participated as separated entities, showing the worst result for Wales which in mathematics was 43rd of the 65 countries and economies. Minister of Education in Wales Huw Lewis expressed disappointment in the results, said that there were no "quick fixes", but hoped that several educational reforms that have been implemented in the last few years would give better results in the next round of tests.[60] The United Kingdom had a greater gap between high- and low-scoring students than the average. There was little difference between public and private schools when adjusted for socio-economic background of students. The gender difference in favour of girls was less than in most other countries, as was the difference between natives and immigrants.[59]

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard warned against putting too much emphasis on the UK's international ranking, arguing that an overfocus on scholarly performances in East Asia might have contributed to the area's low birthrate, which he argued could harm the economic performance in the future more than a good PISA score would outweigh.[61]

In 2013, the Times Educational Supplement (TES) published an article, "Is PISA Fundamentally Flawed?" by William Stewart, detailing serious critiques of PISA's conceptual foundations and methods advanced by statisticians at major universities.[62]

In the article, Professor Harvey Goldstein of the University of Bristol was quoted as saying that when the OECD tries to rule out questions suspected of bias, it can have the effect of "smoothing out" key differences between countries. "That is leaving out many of the important things," he warned. "They simply don't get commented on. What you are looking at is something that happens to be common. But (is it) worth looking at? PISA results are taken at face value as providing some sort of common standard across countries. But as soon as you begin to unpick it, I think that all falls apart."

Queen's University Belfast mathematician Dr. Hugh Morrison stated that he found the statistical model underlying PISA to contain a fundamental, insoluble mathematical error that renders Pisa rankings "valueless".[63] Goldstein remarked that Dr. Morrison's objection highlights "an important technical issue" if not a "profound conceptual error". However, Goldstein cautioned that PISA has been "used inappropriately", contending that some of the blame for this "lies with PISA itself. I think it tends to say too much for what it can do and it tends not to publicise the negative or the weaker aspects." Professors Morrison and Goldstein expressed dismay at the OECD's response to criticism. Morrison said that when he first published his criticisms of PISA in 2004 and also personally queried several of the OECD's "senior people" about them, his points were met with "absolute silence" and have yet to be addressed. "I was amazed at how unforthcoming they were," he told TES. "That makes me suspicious." "Pisa steadfastly ignored many of these issues," he says. "I am still concerned."[64]

Professor Svend Kreiner, of the University of Copenhagen, agreed: "One of the problems that everybody has with PISA is that they don't want to discuss things with people criticising or asking questions concerning the results. They didn't want to talk to me at all. I am sure it is because they can't defend themselves.[64]

United States

Since 2012 a few states have participated in the PISA tests as separate entities. Only the 2012 and 2015 results are available on a state basis. Puerto Rico participated in 2015 as a separate US entity as well.

| Mathematics | Science | Reading | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Mathematics | Science | Reading | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

PISA results for the United States by race and ethnicity

| Mathematics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 2018[65] | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | 2003 |

| Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | |

| Asian | 539 | 498 | 549 | 524 | 494 | 506 |

| White | 503 | 499 | 506 | 515 | 502 | 512 |

| US Average | 478 | 470 | 481 | 487 | 474 | 483 |

| More than one race | 474 | 475 | 492 | 487 | 482 | 502 |

| Hispanic | 452 | 446 | 455 | 453 | 436 | 443 |

| Other | — | 423 | 436 | 460 | 446 | 446 |

| Black | 419 | 419 | 421 | 423 | 404 | 417 |

| Science | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 2018[65] | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 |

| Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | |

| Asian | 551 | 525 | 546 | 536 | 499 |

| White | 529 | 531 | 528 | 532 | 523 |

| US Average | 502 | 496 | 497 | 502 | 489 |

| More than one race | 502 | 503 | 511 | 503 | 501 |

| Hispanic | 478 | 470 | 462 | 464 | 439 |

| Other | — | 462 | 439 | 465 | 453 |

| Black | 440 | 433 | 439 | 435 | 409 |

| Reading | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 2018[65] | 2015 | 2012 | 2009 | 2006 | 2003 | 2000 |

| Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | Score | |

| Asian | 556 | 527 | 550 | 541 | — | 513 | 546 |

| White | 531 | 526 | 519 | 525 | — | 525 | 538 |

| US Average | 505 | 497 | 498 | 500 | — | 495 | 504 |

| More than one race | 501 | 498 | 517 | 502 | — | 515 | — |

| Hispanic | 481 | 478 | 478 | 466 | — | 453 | 449 |

| Black | 448 | 443 | 443 | 441 | — | 430 | 445 |

| Other | — | 440 | 438 | 462 | — | 456 | 455 |

Research on possible causes of PISA disparities in different countries

Although PISA and TIMSS officials and researchers themselves generally refrain from hypothesizing about the large and stable differences in student achievement between countries, since 2000, literature on the differences in PISA and TIMSS results and their possible causes has emerged.[66] Data from PISA have furnished several researchers, notably Eric Hanushek, Ludger Wößmann, Heiner Rindermann, and Stephen J. Ceci, with material for books and articles about the relationship between student achievement and economic development,[67] democratization, and health;[68] as well as the roles of such single educational factors as high-stakes exams,[69] the presence or absence of private schools and the effects and timing of ability tracking.[70]

Comments on accuracy

David Spiegelhalter of Cambridge wrote: "Pisa does present the uncertainty in the scores and ranks - for example the United Kingdom rank in the 65 countries is said to be between 23 and 31. It's unwise for countries to base education policy on their Pisa results, as Germany, Norway and Denmark did after doing badly in 2001."[71]

According to a Forbes opinion article, some countries such as China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Argentina select PISA samples from only the best-educated areas or from their top-performing students, slanting the results.[72]

According to an open letter to Andreas Schleicher, director of PISA, various academics and educators argued that "OECD and Pisa tests are damaging education worldwide".[73]

According to O Estado de São Paulo, Brazil shows a great disparity when classifying the results between public and private schools, where public schools would rank worse than Peru, while private schools would rank better than Finland.[74]

See also

Explanatory notes

References

- "About PISA". OECD PISA. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Berger, Kathleen (3 March 2014). Invitation to The Life Span (second ed.). worth. ISBN 978-1-4641-7205-2.

- "PISA 2018 Results". OECD. 3 December 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Rey O, 'The use of external assessments and the impact on education systems' in CIDREE Yearbook 2010, accessed January 2017". Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- McGaw, B (2008) 'The role of the OECD in international comparative studies of achievement' Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 15:3, 223–243

- Mons N, (2008) 'Évaluation des politiques éducatives et comparaisons internationales', Revue française de pédagogie, 164, juillet-août-septembre 2008 5–13

- Breakspear, S. (2012). "The Policy Impact of PISA: An Exploration of the Normative Effects of International Benchmarking in School System Performance". OECD Education Working Paper. OECD Education Working Papers. 71. doi:10.1787/5k9fdfqffr28-en.

- Barroso, J. and de Carvalho, L.M. (2008) 'Pisa: Un instrument de régulation pour relier des mondes', Revue française de pédagogie, 164, 77–80

- Ertl, H. (2006). "Educational standards and the changing discourse on education: the reception and consequences of the PISA study in Germany". Oxford Review of Education. 32 (5): 619–634. doi:10.1080/03054980600976320. S2CID 144656964.

- Bajomi, I., Berényi, E., Neumann, E. and Vida, J. (2009). 'The Reception of PISA in Hungary' accessed January 2017

- Steiner-Khamsi (2003), cited by Breakspear, S. (2012). "The Policy Impact of PISA: An Exploration of the Normative Effects of International Benchmarking in School System Performance". OECD Education Working Paper. OECD Education Working Papers. 71. doi:10.1787/5k9fdfqffr28-en.

- Mangez, Eric; Cattonar, Branka (September–December 2009). "The status of PISA in the relationship between civil society and the educational sector in French-speaking Belgium". Sísifo: Educational Sciences Journal. Educational Sciences R&D Unit of the University of Lisbon (10): 15–26. ISSN 1646-6500. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "Greger, D. (2008). 'Lorsque PISA importe peu. Le cas de la République Tchèque et de l'Allemagne', Revue française de pédagogie, 164, 91–98. cited in Rey O, 'The use of external assessments and the impact on education systems' in CIDREE Yearbook 2010, accessed January 2017". Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Afonso, Natércio; Costa, Estela (September–December 2009). "The influence of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) on policy decision in Portugal: the education policies of the 17th Portuguese Constitutional Government" (PDF). Sísifo: Educational Sciences Journal. Educational Sciences R&D Unit of the University of Lisbon (10): 53–64. ISSN 1646-6500. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- Rautalin, M.; Alasuutari (2009). "The uses of the national PISA results by Finnish officials in central government". Journal of Education Policy. 24 (5): 539–556. doi:10.1080/02680930903131267. S2CID 154584726.

- Egelund, N. (2008). 'The value of international comparative studies of achievement – a Danish perspective', Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 15, 3, 245–251

- "Behrens, 2006 cited in Rey O, 'The use of external assessments and the impact on education systems in CIDREE Yearbook 2010, accessed January 2017". Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Hefling, Kimberly. "Asian nations dominate international test". Yahoo!.

- "Chapter 2 of the publication 'PISA 2003 Assessment Framework'" (PDF). Pisa.oecd.org.

- Keeley B. PISA, we have a problem… OECD Insights, April 2014.

- Poddiakov, Alexander Complex Problem Solving at PISA 2012 and PISA 2015: Interaction with Complex Reality. // Translated from Russian. Reference to the original Russian text: Poddiakov, A. (2012.) Reshenie kompleksnykh problem v PISA-2012 i PISA-2015: vzaimodeistvie so slozhnoi real'nost'yu. Obrazovatel'naya Politika, 6, 34–53.

- C. Füller: Pisa hat einen kleinen, fröhlichen Bruder. taz, 5.12.2007

- Stanat, P; Artelt, C; Baumert, J; Klieme, E; Neubrand, M; Prenzel, M; Schiefele, U; Schneider, W (2002), PISA 2000: Overview of the study—Design, method and results, Berlin: Max Planck Institute for Human Development

- Mazzeo, John; von Davier, Matthias (2013), Linking Scales in International Large-Scale Assessments, chapter 10 in Rutkowski, L. von Davier, M. & Rutkowski, D. (eds.) Handbook of International Large-Scale Assessment: Background, Technical Issues, and Methods of Data Analysis., New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- von Davier, Matthias; Sinharay, Sandip (2013), Analytics in International Large-Scale Assessments: Item Response Theory and Population Models, chapter 7 in Rutkowski, L. von Davier, M. & Rutkowski, D. (eds.) Handbook of International Large-Scale Assessment: Background, Technical Issues, and Methods of Data Analysis., New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- PISA 2018 Results: Combined Executive Summaries, Volumes I, II, & III (PDF) (Report). OECD. 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- PISA 2018: Insights and Interpretations (PDF), OECD, 3 December 2019, retrieved 4 December 2019

- PISA 2018 in Spain (PDF), OECD, 15 November 2019, retrieved 28 February 2021

- Baldi, Stéphane; Jin, Ying; Skemer, Melanie; Green, Patricia J; Herget, Deborah; Xie, Holly (10 December 2007), Highlights From PISA 2006: Performance of U.S. 15-Year-Old Students in Science and Mathematics Literacy in an International Context (PDF), NCES, retrieved 14 December 2013,

PISA 2006 reading literacy results are not reported for the United States because of an error in printing the test booklets. Furthermore, as a result of the printing error, the mean performance in mathematics and science may be misestimated by approximately 1 score point. The impact is below one standard error.

- PISA 2009 Results: Executive Summary (PDF), OECD, 7 December 2010

- ACER releases results of PISA 2009+ participant economies, ACER, 16 December 2011, archived from the original on 14 December 2013

- Walker, Maurice (2011), PISA 2009 Plus Results (PDF), OECD, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2011, retrieved 28 June 2012

- PISA 2012 Results in Focus (PDF), OECD, 3 December 2013, retrieved 4 December 2013

- Tom Phillips (3 December 2013) OECD education report: Shanghai's formula is world-beating The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 December 2013

- Cook, Chris (7 December 2010), "Shanghai tops global state school rankings", Financial Times, retrieved 28 June 2012

- Mance, Henry (7 December 2010), "Why are Chinese schoolkids so good?", Financial Times, retrieved 28 June 2012

- Coughlan, Sean (26 August 2014). "Pisa tests to include many more Chinese pupils". BBC News.

- Helen Gao, "Shanghai Test Scores and the Mystery of the Missing Children", New York Times, 23 January 2014. For Schleicher's initial response to these criticisms see his post, "Are the Chinese Cheating in PISA Or Are We Cheating Ourselves?" on the OECD's website blog, Education Today, 10 December 2013.

- "William Stewart, "More than a quarter of Shanghai pupils missed by international Pisa rankings", Times Educational Supplement, March 6, 2014". Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- http://www.oecd.org/china/Education-in-China-a-snapshot.pdf

- Howse, Patrick (18 February 2014). "Shanghai visit for minister to learn maths lessons". BBC News. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Coughlan, Sean (12 March 2014). "Shanghai teachers flown in for maths". BBC News. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "Britain invites 120 Chinese Maths teachers for aided schools". India Today. 20 July 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- "Scores bolster case for Shanghai math in British schools | The Star". www.thestar.com.my. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Turner, Camilla (3 December 2019). "Britain jumps up international maths rankings following Chinese-style teaching". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Starkey, Hannah (5 December 2019). "UK Boost International Maths Ranking After Adopting Chinese-Style Teaching". True Education Partnerships. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- PISA 2012: Proficiency of Finnish youth declining University of Jyväskylä. Retrieved 9 December 2013

- Hemali Chhapia, TNN (3 August 2012). "India backs out of global education test for 15-year-olds". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013.

- PISA (Program for International Student Assessment): OECD, Drishti, 1 Sept 2021.

- "Poor PISA score: Govt blames 'disconnect' with India". The Indian Express. 3 September 2012.

- "India chickens out of international students assessment programme again". The Times of India. 1 June 2013.

- "PISA Tests: India to take part in global teen learning test in 2021". The Indian Express. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- "Ong: Did ministry try to rig results for Pisa 2015 report?". 8 December 2016.

- "Who's telling the truth about M'sia's Pisa 2015 scores?". 9 December 2016.

- "Malaysian PISA results under scrutiny for lack of evidence – School Advisor". 8 December 2016.

- Lars Näslund (3 December 2013) Svenska skolan rasar i stor jämförelse Expressen. Retrieved 4 December 2013 (in Swedish)

- Jens Kärrman (3 December 2013) Löfven om Pisa: Nationell kris Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 8 December 2013 (in Swedish)

- "Sveriges PISA-framgång bygger på falska siffror". 2 June 2020.

- Adams, Richard (3 December 2013), "UK students stuck in educational doldrums, OECD study finds", The Guardian, retrieved 4 December 2013

- Pisa ranks Wales' education the worst in the UK BBC. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- Ambrose Evans-Pritchard (3 December 2013) Ambrose Evans-Pritchard Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- "William Stewart, "Is Pisa fundamentally flawed?" Times Educational Supplement, July 26, 2013". Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- Morrison, Hugh (2013). "A fundamental conundrum in psychology's standard model of measurement and its consequences for PISA global rankings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Stewart, "Is PISA fundamentally flawed?" TES (2013).

- "Highlights of U.S. PISA 2018 Results Web Report" (PDF).

- Hanushek, Eric A., and Ludger Woessmann. 2011. "The economics of international differences in educational achievement." In Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 3, edited by Eric A. Hanushek, Stephen Machin, and Ludger Woessmann. Amsterdam: North Holland: 89–200.

- Hanushek, Eric; Woessmann, Ludger (2008), "The role of cognitive skills in economic development" (PDF), Journal of Economic Literature, 46 (3): 607–668, doi:10.1257/jel.46.3.607

- Rindermann, Heiner; Ceci, Stephen J (2009), "Educational policy and country outcomes in international cognitive competence studies", Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4 (6): 551–577, doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01165.x, PMID 26161733, S2CID 9251473

- Bishop, John H (1997). "The effect of national standards and curriculum-based exams on achievement". American Economic Review. Papers and Proceedings. 87 (2): 260–264. JSTOR 2950928.

- Hanushek, Eric; Woessmann, Ludger (2006), "Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across countries" (PDF), Economic Journal, 116 (510): C63–C76, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01076.x

- Alexander, Ruth (10 December 2013). "How accurate is the Pisa test?". BBC News. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Flows, Capital. "Are The PISA Education Results Rigged?". Forbes. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Guardian Staff (6 May 2014). "OECD and Pisa tests are damaging education worldwide – academics". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Cafardo, Rafael (4 December 2019). "Escolas privadas de elite do Brasil superam Finlândia no Pisa, rede pública vai pior do que o Peru". Retrieved 4 December 2019 – via www.estadao.com.br.

External links

- OECD/PISA website

- OECD (1999): Measuring Student Knowledge and Skills: A New Framework for Assessment. Paris: OECD, ISBN 92-64-17053-7

- OECD (2014): PISA 2012 results: Creative problem solving: Students' skills in tackling real-life problems (Volume V)

- OECD's Education GPS: Interactive data from PISA 2015

- PISA Data Explorer

- Gunda Tire: "Estonians believe in education, and this belief has been essential for centuries"—Interview of Gunda Tire, OECD PISA National Project Manager, for Caucasian Journal