Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (French: Traité de Trianon; Hungarian: Trianoni békeszerződés; Italian: Trattato del Trianon; Romanian: Tratatul de la Trianon) often referred to as the Peace Dictate of Trianon[5][6][7][8][9] or Dictate of Trianon[10][11] in Hungary, was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It formally ended World War I between most of the Allies of World War I[lower-alpha 1] and the Kingdom of Hungary.[12][13][14][15] French diplomats played the major role in designing the treaty, with a view to establishing a French-led coalition of the newly formed states. It regulated the status of the Kingdom of Hungary and defined its borders generally within the ceasefire lines established in November–December 1918 and left Hungary as a landlocked state that included 93,073 square kilometres (35,936 sq mi), 28% of the 325,411 square kilometres (125,642 sq mi) that had constituted the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary (the Hungarian half of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy). The truncated kingdom had a population of 7.6 million, 36% compared to the pre-war kingdom's population of 20.9 million.[16] Though the areas that were allocated to neighbouring countries had a majority of non-Hungarians, in them lived 3.3 million Hungarians – 31% of the Hungarians – who then became minorities.[17][18][19][20] The treaty limited Hungary's army to 35,000 officers and men, and the Austro-Hungarian Navy ceased to exist. These decisions and their consequences have been the cause of deep resentment in Hungary ever since.[21]

| Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Hungary | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Arrival of the two signatories, Ágost Benárd and Alfréd Drasche-Lázár, on 4 June 1920 at the Grand Trianon in Versailles | |

| Signed | 4 June 1920 |

| Location | Versailles, France |

| Effective | 26 July 1921 |

| Parties | 1. Principal Allied and Associated Powers Other Allied Powers 2. Central Powers |

| Depositary | French Government |

| Languages | French, English, Italian |

| Full text | |

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

- Revolutions of 1917–1923

- Aftermath of World War I 1918–1939

- Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War 1918–1925

- Province of the Sudetenland 1918–1920

- 1918–1920 unrest in Split

- Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919

- Heimosodat 1918–1922

- Austro-Slovene conflict in Carinthia 1918–1919

- Hungarian–Romanian War 1918–1919

- Hungarian–Czechoslovak War 1918–1919

- 1919 Egyptian Revolution

- Christmas Uprising 1919

- Irish War of Independence 1919

- Comintern World Congresses 1919–1935

- Treaty of Versailles 1919

- Shandong Problem 1919–1922

- Polish–Soviet War 1919–1921

- Polish–Czechoslovak War 1919

- Polish–Lithuanian War 1919–1920

- Silesian Uprisings 1919–1921

- Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1919

- Turkish War of Independence 1919–1923

- Venizelos–Tittoni agreement 1919

- Italian Regency of Carnaro 1919–1920

- Iraqi Revolt 1920

- Treaty of Trianon 1920

- Vlora War 1920

- Treaty of Rapallo 1920

- Little Entente 1920–1938

- Treaty of Tartu (Finland–Russia) 1920–1938

- Mongolian Revolution of 1921

- Soviet intervention in Mongolia 1921–1924

- Uprising in West Hungary 1921–1922

- Franco-Polish alliance 1921–1940

- Polish–Romanian alliance 1921–1939

- Genoa Conference (1922)

- Treaty of Rapallo (1922)

- March on Rome 1922

- Sun–Joffe Manifesto 1923

- Corfu incident 1923

- Occupation of the Ruhr 1923–1925

- Treaty of Lausanne 1923–1924

- Mein Kampf 1925

- Second Italo-Senussi War 1923–1932

- First United Front 1923–1927

- Dawes Plan 1924

- Treaty of Rome (1924)

- Soviet–Japanese Basic Convention 1925

- German–Polish customs war 1925–1934

- Treaty of Nettuno 1925

- Locarno Treaties 1925

- Anti-Fengtian War 1925–1926

- Treaty of Berlin (1926)

- May Coup (Poland) 1926

- Northern Expedition 1926–1928

- Nanking incident of 1927

- Chinese Civil War 1927–1937

- Jinan incident 1928

- Huanggutun incident 1928

- Italo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1928

- Chinese reunification 1928

- Lateran Treaty 1928

- Central Plains War 1929–1930

- Young Plan 1929

- Sino-Soviet conflict (1929)

- Great Depression 1929

- London Naval Treaty 1930

- Kumul Rebellion 1931–1934

- Japanese invasion of Manchuria 1931

- Pacification of Manchukuo 1931–1942

- January 28 incident 1932

- Soviet–Japanese border conflicts 1932–1939

- Geneva Conference 1932–1934

- May 15 incident 1932

- Lausanne Conference of 1932

- Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact 1932

- Soviet–Finnish Non-Aggression Pact 1932

- Proclamation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 1932

- Defense of the Great Wall 1933

- Battle of Rehe 1933

- Nazis' rise to power in Germany 1933

- Reichskonkordat 1933

- Tanggu Truce 1933

- Italo-Soviet Pact 1933

- Inner Mongolian Campaign 1933–1936

- Austrian Civil War 1934

- Balkan Pact 1934–1940

- July Putsch 1934

- German–Polish declaration of non-aggression 1934–1939

- Baltic Entente 1934–1939

- 1934 Montreux Fascist conference

- Stresa Front 1935

- Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance 1935

- Soviet–Czechoslovakia Treaty of Mutual Assistance 1935

- He–Umezu Agreement 1935

- Anglo-German Naval Agreement 1935

- December 9th Movement

- Second Italo-Ethiopian War 1935–1936

- February 26 incident 1936

- Remilitarization of the Rhineland 1936

- Soviet-Mongolian alliance 1936

- Arab revolt in Palestine 1936–1939

- Spanish Civil War 1936–1939

- Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936

- Italo-German "Axis" protocol 1936

- Anti-Comintern Pact 1936

- Suiyuan campaign 1936

- Xi'an Incident 1936

- Second Sino-Japanese War 1937–1945

- USS Panay incident 1937

- Anschluss Mar. 1938

- 1938 Polish ultimatum to Lithuania Mar. 1938

- Easter Accords April 1938

- May Crisis May 1938

- Battle of Lake Khasan July–Aug. 1938

- Salonika Agreement July 1938

- Bled Agreement Aug. 1938

- Undeclared German–Czechoslovak War Sep. 1938

- Munich Agreement Sep. 1938

- First Vienna Award Nov. 1938

- German occupation of Czechoslovakia Mar. 1939

- Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine Mar. 1939

- German ultimatum to Lithuania Mar. 1939

- Slovak–Hungarian War Mar. 1939

- Final offensive of the Spanish Civil War Mar.–Apr. 1939

- Danzig crisis Mar.–Aug. 1939

- British guarantee to Poland Mar. 1939

- Italian invasion of Albania Apr. 1939

- Soviet–British–French Moscow negotiations Apr.–Aug. 1939

- Pact of Steel May 1939

- Battles of Khalkhin Gol May–Sep. 1939

- Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact Aug. 1939

- Invasion of Poland Sep. 1939

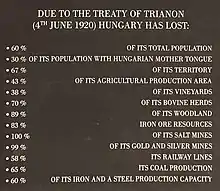

The principal beneficiaries were the Kingdom of Romania, the Czechoslovak Republic, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), and the First Austrian Republic. One of the main elements of the treaty was the doctrine of "self-determination of peoples", and it was an attempt to give the non-Hungarians their own national states.[22] In addition, Hungary had to pay war reparations to its neighbours. The treaty was dictated by the Allies rather than negotiated, and the Hungarians had no option but to accept its terms.[22] The Hungarian delegation signed the treaty under protest, and agitation for its revision began immediately.[18][23]

The current boundaries of Hungary are for the most part the same as those defined by the Treaty of Trianon, with minor modifications until 1924 regarding the Hungarian-Austrian border and the transfer of three villages to Czechoslovakia in 1947.[24][25]

After World War I, despite the "self-determination of peoples" idea of the Allied Powers, only one plebiscite was permitted (later known as the Sopron plebiscite) to settle disputed borders on the former territory of the Kingdom of Hungary,[26] settling a smaller territorial dispute between the First Austrian Republic and the Kingdom of Hungary, because some months earlier, the Rongyos Gárda launched a series of attacks to oust the Austrian forces that entered the area. During the plebiscite in late 1921, the polling stations were supervised by British, French, and Italian army officers of the Allied Powers.[27]

Background

First World War and Austro-Hungarian Armistice

On 28 June 1914, the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist.[28] This caused a rapidly escalating July Crisis resulting in Austria-Hungary declaring war on Serbia, followed quickly by the entry of most European powers into the First World War.[29] Two alliances faced off, the Central Powers (led by Germany) and the Triple Entente (led by Britain, France and Russia). In 1918 Germany tried to overwhelm the Allies on the Western Front but failed. Instead the Allies began a successful counteroffensive and forced the Armistice of 11 November 1918 that resembled a surrender by the Central Powers.[30]

On 6 April 1917, the United States entered the war against Germany and in December 1917 against Austria-Hungary. The American war aim was to end aggressive militarism as shown by Berlin and Vienna. The United States never formally joined the Allies. President Woodrow Wilson acted as an independent force, and his Fourteen Points was accepted by Germany as a basis for the armistice of November 1918. It outlined a policy of free trade, open agreements, and democracy. While the term was not used, self-determination was assumed. It called for a negotiated end to the war, international disarmament, the withdrawal of the Central Powers from occupied territories, the creation of a Polish state, the redrawing of Europe's borders along ethnic lines, and the formation of a League of Nations to guarantee the political independence and territorial integrity of all states.[31][32] It called for a just and democratic peace uncompromised by territorial annexation. Point ten announced Wilson's "wish" that the peoples of Austria-Hungary be given autonomy—a point that Vienna rejected.[33]

Germany, the major ally of Austria-Hungary in World War I, suffered numerous losses during the Hundred Days Offensive between August and November 1918 and was in negotiation of armistice with Allied Powers from the beginning of October 1918. Between 15 and 29 September 1918, Franchet d'Espèrey, in command of a relative small army of Greeks (9 divisions), French (6 divisions), Serbs (6 divisions), British (4 divisions) and Italians (1 division), staged a successful Vardar offensive in Vardar Macedonia that ended by taking Bulgaria out of the war.[34] That collapse of the Southern (Italian) Front was one of several developments that effectively triggered the November 1918 armistice.[35] By the end of October 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Army was so fatigued that its commanders were forced to seek a ceasefire. Czechoslovakia and the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs were proclaimed, and troops started deserting, disobeying orders and retreating. Many Czechoslovak troops, in fact, started working for the Allied cause, and in September 1918, five Czechoslovak Regiments were formed in the Italian Army. The troops of Austria-Hungary started a chaotic withdrawal during the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, and Austria-Hungary began to negotiate a truce on 28 October.

Aster Revolution and the First Hungarian Republic

During the war, Count Mihály Károlyi led a small but very active pacifist anti-war maverick faction in the Hungarian parliament.[36] He even organized covert contacts with British and French diplomats in Switzerland.[37] The Austro-Hungarian monarchy politically collapsed and disintegrated as a result of a defeat in the Italian front. On 31 October 1918, in the midst of armistice negotiations, the Aster Revolution in Budapest brought the liberal Károlyi, a supporter of the Allies, to power. King Charles had no other option than the appointment of Károlyi as prime minister of Hungary. On 25 October 1918 Károlyi had formed the Hungarian National Council. The Hungarian Royal Honvéd army still had more than 1,400,000 soldiers[38][39] when Károlyi was announced as prime minister. Károlyi yielded to President Wilson's demand for pacifism by ordering the unilateral self-disarmament of the Hungarian army. This happened under the direction of Minister of War Béla Linder on 2 November 1918[40][41] When Oszkár Jászi became the new Minister for National Minorities of Hungary, he immediately offered democratic referendums about the disputed borders for minorities; however, the political leaders of those minorities refused the very idea of democratic referendums regarding disputed territories at the Paris peace conference.[42] Disarmament of its army meant that Hungary was to remain without a national defence at a time of particular vulnerability. The unilateral self-disarmament made the occupation of Hungary directly possible for the relatively small armies of Romania, the Franco-Serbian army, and the armed forces of the newly established Czechoslovakia.[43][44][45][46] After self-disarmament, Czech, Serbian, and Romanian political leaders chose to attack Hungary instead of holding democratic plebiscites concerning the disputed areas.[47]

On the request of the Austro-Hungarian government, an armistice was granted to Austria-Hungary on 3 November 1918 by the Allies.[48] Military and political events changed rapidly and drastically after the Hungarian unilateral disarmament:

- On 5 November 1918, the Serbian army, with the help of the French army, crossed the southern borders.

- On 8 November, the Czechoslovak army crossed the northern borders.

- On 10 November d'Espérey's army crossed the Danube River and was poised to enter the Hungarian heartland.

- On 11 November Germany signed an armistice with Allies, under which they had to immediately withdraw all German troops in Romania and in the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Russian Empire back to German territory and Allies to have access to these countries.[49]

- On 13 November, the Romanian army crossed the eastern borders of the Kingdom of Hungary.

During the rule of Károlyi's pacifist cabinet, Hungary rapidly lost control over approximately 75% of its former pre-WWI territories (325,411 km2 (125,642 sq mi)) without a fight and was subject to foreign occupation.[50] The Armistice of 3 November was completed as regards Hungary on 13 November, when Károlyi signed the Armistice of Belgrade with the Allied nations, in order that a Treaty of Peace might be concluded.[51][52] It limited the size of the Hungarian army to six infantry and two cavalry divisions.[53] Demarcation lines defining the territory to remain under Hungarian control were made. The lines would apply until definitive borders could be established. Under the terms of the armistice, Serbian and French troops advanced from the south, taking control of the Banat and Croatia. Romanian forces were permitted to advance to the River Mureș (Maros). However, on 14 November, Serbia occupied Pécs.[54][55] General Franchet d'Espèrey followed up the victory by overrunning much of the Balkans, and by the war's end his troops had penetrated well into Hungary. In mid-November 1918, the Czechoslovak troops advanced into the Upper Hungary, but were repulsed by the Hungarian troops. But following a demand by the Entente to allow the Czechoslovak occupation in the North on 3 December 1918, Budapest agreed that the Czechs would occupy the North-West of Upper Hungary. Late December 1918, Hungary agreed to extend the Czech zone of occupation to Pozsony (Bratislava), Komarno, Kosice and Uzhhorod. By late January 1919, the Czech troops advanced into these areas. The Budapest approval for the Czech advancement in Upper Hungary was largely explained by the Hungarian desire to reopen trade with Czech lands and to obtain crucially needed coal amidst an energy crisis.

After King Charles's withdrawal from government on 16 November 1918, Károlyi proclaimed the First Hungarian Republic, with himself as provisional president of the republic.

Fall of the liberal First Hungarian Republic and communist coup d'état

The Károlyi government failed to manage both domestic and military issues and lost popular support. On 20 March 1919, Béla Kun, who had been imprisoned in the Markó Street prison, was released.[56] On 21 March, he led a successful communist coup d'état; Károlyi was deposed and arrested.[57] Kun formed a social democratic, communist coalition government and proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Days later the communists purged the social democrats from the government.[58][59] The Hungarian Soviet Republic was a small communist rump state.[60] When the Republic of Councils in Hungary was established, it controlled only approximately 23% of Hungary's historic territory. After the Communist takeover, the Allies sent a new diplomatic mission to Budapest, led by General Jan Smuts. During these talks with Smuts, Kun insisted that his government would abide by the Belgrade ceasefire and recognise the right to self-determination of the various ethnic groups living in Hungary. In return, Kun urged an end to the Allied trade blockade, particularly by the Czechs, and to allow fuel and food to be imported into Hungary.[61]

The communists remained bitterly unpopular[62] in the Hungarian countryside, where the authority of that government was often nonexistent.[63] Rather than divide the big estates among the peasants – which might have gained their support for the government, but would have created a class of small-holding farmers the communist government proclaimed the nationalization of the estates. But having no skilled people to manage the estates, the communists had no choice but to leave the existing estate managers in place. These, while formally accepting their new government bosses, in practice retained their loyalty to the deposed aristocratic owners. The peasants felt that the revolution had no real effect on their lives and thus had no reason to support it. The communist party and communist policies only had real popular support among the proletarian masses of large industrial centers—especially in Budapest—where the working class represented a high proportion of the inhabitants. The communist government followed the Soviet model: the party established its terror groups (like the infamous Lenin Boys) to "overcome the obstacles" in the Hungarian countryside. This was later known as the Red Terror in Hungary.

In late May, after the Entente military representative demanded more territorial concessions from Hungary, Kun attempted to "fulfill" his promise to adhere to Hungary's historical borders. The men of the Hungarian Red Army were recruited mainly from the volunteers of the Budapest proletariat.[64] On 20 May 1919, a force under Colonel Aurél Stromfeld attacked and routed Czechoslovak troops from Miskolc. The Romanian Army attacked the Hungarian flank with troops from the 16th Infantry Division and the Second Vânători Division, aiming to maintain contact with the Czechoslovak Army. Hungarian troops prevailed, and the Romanian Army retreated to its bridgehead at Tokaj. There, between 25 and 30 May, Romanian forces were required to defend their position against Hungarian attacks. On 3 June, Romania was forced into further retreat but extended its line of defence along the Tisza River and reinforced its position with the 8th Division, which had been moving forward from Bukovina since 22 May. Hungary then controlled the territory almost to its old borders; regained control of industrial areas around Miskolc, Salgótarján, Selmecbánya (Banská Štiavnica), Kassa (Košice).

In June, the Hungarian Red Army invaded the eastern part of the so-called Upper Hungary, now claimed by the newly forming Czechoslovak state. The Hungarian Red Army achieved some military success early on: under the leadership of Colonel Aurél Stromfeld, it ousted Czechoslovak troops from the north and planned to march against the Romanian Army in the east. Kun ordered the preparation of an offensive against Czechoslovakia, which would increase his domestic support by making good on his promise to restore Hungary's borders. The Hungarian Red Army recruited men between 19 and 25 years of age. Industrial workers from Budapest volunteered. Many former Austro-Hungarian officers re-enlisted for patriotic reasons. The Hungarian Red Army moved its 1st and 5th artillery divisions—40 battalions—to Upper Hungary.

Despite promises for the restoration of the former borders of Hungary, the communists declared the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic in Prešov (Eperjes) on 16 June 1919.[65] After the proclamation of the Slovak Soviet Republic, the Hungarian nationalists and patriots soon realized that the new communist government had no intentions to recapture the lost territories, only to spread communist ideology and establish other communist states in Europe, thus sacrificing Hungarian national interests.[66] The Hungarian patriots and professional military officers in the Red Army saw the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic as a betrayal, and their support for the government began to erode. Despite a series of military victories against the Czechoslovak army, the Hungarian Red Army started to disintegrate due to tension between nationalists and communists during the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic. The concession eroded support of the communist government among professional military officers and nationalists in the Hungarian Red Army; even the chief of the general staff Aurél Stromfeld, resigned his post in protest.[67]

When the French promised the Hungarian government that Romanian forces would withdraw from the Tiszántúl, Kun withdrew from Czechoslovakia his remaining military units who had remained loyal after the political fiasco with the Slovak Soviet Republic. Kun then unsuccessfully tried to turn the remaining units of the demoralized Hungarian Red Army on the Romanians.

Treaty preparation

The Hungarian "Conditions of Peace" were dated 15 January 1920, and their "Observations" handed in on 20 February. French diplomats played the major role in the drafting, and Hungarians were kept in the dark. Their long-term goal was to build a coalition of small new nations led by France and capable of standing up to Russia or Germany. This led to the "Little Entente" of Czechoslovakia, Romania and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[68] The lengthy negotiation process was recorded on a daily basis by János Wettstein, deputy first secretary of the Hungarian delegation.[69] The treaty of peace in final form was submitted to the Hungarians on 6 May and signed by them in Grand Trianon[70] on 4 June 1920, entering into force on 26 July 1921.[71] The United States did not ratify the Treaty of Trianon. Instead it negotiated a separate peace treaty that did not contradict the terms of the Trianon treaty.[33]

Borders of Hungary

_-_full.jpg.webp)

| History of Hungary |

|---|

|

|

|

The Hungarian government terminated its union with Austria on 31 October 1918, officially dissolving the Austro-Hungarian state. The de facto temporary borders of independent Hungary were defined by the ceasefire lines in November–December 1918. Compared with the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary, these temporary borders did not include:

- Part of Transylvania south of the Mureș River and east of the Someș River, which came under the control of Romania (cease-fire agreement of Belgrade signed on 13 November 1918).

- The General Council of the Saxons in Nagyszeben (now Sibiu in Romania) decided in question of Transylvania to choose clear neutrality, without committing themselves either to the Hungarian or the Romanian side on 25 November 1918.[72]

- The Romanian Army occupied Marosvásárhely (now Târgu Mureș in Romania), the most important town of Székely Land in Transylvania. On the same day the National Assembly of Székelys in Marosvásárhely reaffirms their support to the territorial integrity of Hungary on 25 November 1918.

- On 1 December 1918, the Great National Assembly of Alba Iulia declared union with the Kingdom of Romania.[73]

- In response, a Hungarian General Assembly in Kolozsvár (now Cluj in Romania), the most important Hungarian town in Transylvania, reaffirms the loyalty of Hungarians from Transylvania to Hungary on 22 December 1918.

- Slovakia was proclaimed as part of Czechoslovakia (status quo set by the Czechoslovak legions and accepted by the Entente on 25 November 1918). Afterwards, the Slovak politician Milan Hodža discussed with the Hungarian Minister of Defence, Albert Bartha, a temporary demarcation line that left between 650,000 and 886,000 Hungarians in the newly formed Czechoslovakia and between 142,000 and 399,000 Slovaks in the remainder of Hungary (the discrepancy was caused by the different way census was collected in Hungary and Czechoslovakia). That was signed on 6 December 1918.

- South Slavic lands, which, after the war, were organised into two political formations – the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and Banat, Bačka and Baranja, which both came under control of South Slavs, according to the ceasefire agreement of Belgrade signed on 13 November 1918. Previously, on 29 October 1918, the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia parliament, an autonomous kingdom within Transleithania, terminated[74] the union[75] with the Kingdom of Hungary and on 30 October 1918 the Hungarian diet adopted a motion declaring that the constitutional relations between the two states had ended.[76] Croatia-Slavonia was included in a newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs (which also included some other South Slavic territories, formerly administered by Austria-Hungary) on 29 October 1918. This state and the Kingdom of Serbia formed the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Yugoslavia) on 1 December 1918.

The territories of Banat, Bačka and Baranja (which included most of the pre-war Hungarian counties of Baranya, Bács-Bodrog, Torontál, and Temes) came under military control by the Kingdom of Serbia and political control by local South Slavs. The Great People's Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs in Banat, Bačka and Baranja declared union of this region with Serbia on 25 November 1918. The ceasefire line had the character of a temporary international border until the treaty. The central parts of Banat were later assigned to Romania, respecting the wishes of Romanians from this area, which, on 1 December 1918, were present in the National Assembly of Romanians in Alba Iulia, which voted for union with the Kingdom of Romania.

- The city of Rijeka was occupied by the Italian nationalists group. Its affiliation was a matter of international dispute between the Kingdom of Italy and Yugoslavia.

- Croatian-populated territories in modern Međimurje remained under Hungarian control after the Armistice of Belgrade of 13 November 1918. After the Međimurje was occupied by forces led by Slavko Kvaternik on 24 December 1918, this region declared separation from Hungary and entry into Yugoslavia at the popular assembly of 9 January 1919.[77][78]

After the Romanian Army advanced beyond this cease-fire line, the Entente powers asked Hungary (Vix Note) to acknowledge the new Romanian territorial gains by a new line set along the Tisza river. Unable to reject these terms and unwilling to accept them, the leaders of the Hungarian Democratic Republic resigned and the Communists seized power. In spite of the country being under Allied blockade, the Hungarian Soviet Republic was formed and the Hungarian Red Army was rapidly set up. This army was initially successful against the Czechoslovak Legions, due to covert food[79] and arms aid from Italy.[80] This made it possible for Hungary to reach nearly the former Galician (Polish) border, thus separating the Czechoslovak and Romanian troops from each other.

After a Hungarian-Czechoslovak cease-fire signed on 1 July 1919, the Hungarian Red Army left parts of Slovakia by 4 July, as the Entente powers promised to invite a Hungarian delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference. In the end, this particular invitation was not issued. Béla Kun, leader of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, then turned the Hungarian Red Army on the Romanian Army and attacked at the Tisza river on 20 July 1919. After fierce fighting that lasted some five days, the Hungarian Red Army collapsed. The Royal Romanian Army marched into Budapest on 4 August 1919.

The Hungarian state was restored by the Entente powers, helping Admiral Horthy into power in November 1919. On 1 December 1919, the Hungarian delegation was officially invited to the Versailles Peace Conference; however, the newly defined borders of Hungary were nearly concluded without the presence of the Hungarians.[81] During prior negotiations, the Hungarian party, along with the Austrian, advocated the American principle of self-determination: that the population of disputed territories should decide by free plebiscite to which country they wished to belong.[81][82] This view did not prevail for long, as it was disregarded by the decisive French and British delegates.[83] According to some opinions, the Allies drafted the outline of the new frontiers[84] with little or no regard to the historical, cultural, ethnic, geographic, economic and strategic aspects of the region.[81][84][85] The Allies assigned territories that were mostly populated by non-Hungarian ethnicities to successor states, but also allowed these states to absorb sizeable territories that were mainly inhabited by Hungarian-speaking populations. For instance, Romania gained all of Transylvania, which was home to 2,800,000 Romanians, but also contained a significant minority of 1,600,000 Hungarians and about 250,000 Germans.[86] The intent of the Allies was principally to strengthen these successor states at the expense of Hungary. Although the countries that were the main beneficiaries of the treaty partially noted the issues, the Hungarian delegates tried to draw attention to them. Their views were disregarded by the Allied representatives.

Some predominantly Hungarian settlements, consisting of more than two million people, were situated in a typically 20–50 km (12–31 mi) wide strip along the new borders in foreign territory. More concentrated groups were found in Czechoslovakia (parts of southern Slovakia), Yugoslavia (parts of northern Délvidék), and Romania (parts of Transylvania).

The final borders of Hungary were defined by the Treaty of Trianon signed on 4 June 1920. Beside exclusion of the previously mentioned territories, they did not include:

- the rest of Transylvania, which together with some additional parts of the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary became part of Romania;

- Carpathian Ruthenia, which became part of Czechoslovakia, pursuant to the Treaty of Saint-Germain in 1919;[87]

- most of Burgenland, which became part of Austria, also pursuant to the Treaty of Saint-Germain (the district of Sopron opted to remain within Hungary after a plebiscite held in December 1921, the only place where a plebiscite was held and factored in the decision);

- Međimurje and the 2/3 of the Slovene March or Vendvidék (now Prekmurje), which became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

By the Treaty of Trianon, the cities of Pécs, Mohács, Baja and Szigetvár, which were under Serb-Croat-Slovene administration after November 1918, were assigned to Hungary. An arbitration committee in 1920 assigned small northern parts of the former Árva and Szepes counties of the Kingdom of Hungary with Polish majority population to Poland. After 1918, Hungary did not have access to the sea, which pre-war Hungary formerly had directly through the Rijeka coastline and indirectly through Croatia-Slavonia.

Representatives of small nations living in the former Austria-Hungary and active in the Congress of Oppressed Nations regarded the treaty of Trianon for being an act of historical righteousness[88] because a better future for their nations was "to be founded and durably assured on the firm basis of world democracy, real and sovereign government by the people, and a universal alliance of the nations vested with the authority of arbitration" while at the same time making a call for putting an end to "the existing unbearable domination of one nation over the other" and making it possible "for nations to organize their relations to each other on the basis of equal rights and free conventions". Furthermore, they believed the treaty would help toward a new era of dependence on international law, the fraternity of nations, equal rights, and human liberty as well as aid civilisation in the effort to free humanity from international violence.[89]

Results and consequences

Irredentism—the demand for reunification of Hungarian peoples—became a central theme of Hungarian politics and diplomacy.[94]

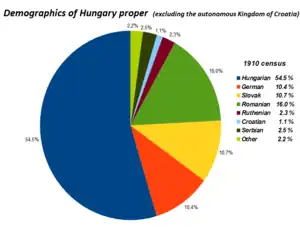

1910 census

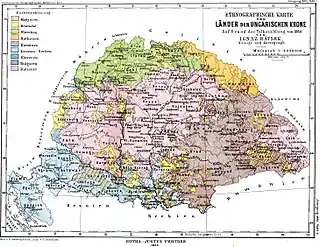

The last census before the Treaty of Trianon was held in 1910. This census recorded population by language and religion but not by ethnicity. On the other hand, in pre-WW1 era Europe, there were only language censuses in a few countries, but the first ethnic censuses were not implemented in Europe until the interwar period.[95] However, it is generally accepted that the largest ethnic group in the Kingdom of Hungary in this time were the Hungarians. According to the census, speakers of the Hungarian language included approximately 48% of the population of the kingdom (including the autonomous Croatia-Slavonia) and 54% of the population of the territory referred to as "Hungary proper", i.e. excluding Croatia. Within the borders of "Hungary proper" numerous ethnic minorities were present: 16.1% Romanians, 10.5% Slovaks, 10.4% Germans, 2.5% Ruthenians, 2.5% Serbs and 8% others.[96] 5% of the population of "Hungary proper" were Jews, who were included in speakers of the Hungarian language.[97] The population of the autonomous Croatia-Slavonia was mostly composed of Croats and Serbs (who together counted 87% of population).

Criticism of the 1910 census

The census of 1910 classified the residents of the Kingdom of Hungary by their native languages[98] and religions, so it presents the preferred language of the individual, which may or may not correspond to the individual's ethnic identity. To make the situation even more complex, in the multilingual kingdom there were territories with ethnically mixed populations where people spoke two or even three languages natively. For example, in the territory what is today Slovakia (then part of Upper Hungary) 18% of the Slovaks, 33% of the Hungarians and 65% of the Germans were bilingual. In addition, 21% of the Germans spoke both Slovak and Hungarian beside German.[99] These reasons are ground for debate about the accuracy of the census.

While several demographers (David W. Paul,[100] Peter Hanak, László Katus[101]) state that the outcome of the census is reasonably accurate (assuming that it is also properly interpreted), others believe that the 1910 census was manipulated[102][103] by exaggerating the percentage of the speakers of Hungarian, pointing to the discrepancy between an improbably high growth of the Hungarian-speaking population and the decrease of percentual participation of speakers of other languages through Magyarization in the late 19th century.[104] For example, the 1921 census in Czechoslovakia (only one year after the Treaty of Trianon) shows 21% Hungarians in Slovakia,[105] compared to 30% based on 1910 census.

Some Slovak demographers (such as Ján Svetoň and Julius Mesaros) dispute the result of every pre-war census.[100] Owen Johnson, an American historian, accepts the numbers of the earlier censuses up to the one in 1900, according to which the proportion of the Hungarians was 51.4%,[96] but he neglects the 1910 census as he thinks the changes since the last census are too big.[100] It is also argued that there were different results in previous censuses in the Kingdom of Hungary and subsequent censuses in the new states. Considering the size of discrepancies, some demographers are on the opinion that these censuses were somewhat biased in the favour of the respective ruling nation.[106]

Distribution of the non-Hungarian and Hungarian populations

The number of non-Hungarian and Hungarian communities in the different areas based on the census data of 1910 (in this, people were not directly asked about their ethnicity, but about their native language). The present day location of each area is given in parentheses.

| Region | Main spoken language | Hungarian language | Other languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transylvania and parts of Partium, Banat (Romania) | Romanian – 2,819,467 (54%) | 1,658,045 (31.7%) | German – 550,964 (10.5%) |

| Upper Hungary (restricted to the territory of today's Slovakia) | Slovak – 1,688,413 (57.9%) | 881,320 (30.2%) | German – 198,405 (6.8%) |

| Délvidék (Vojvodina, Serbia) | Serbo-Croatian – 601,770 (39.8%) * Serbian – 510,754 (33.8%) * Croatian, Bunjevac and Šokac – 91,016 (6%) |

425,672 (28.1%) | German – 324,017 (21.4%) |

| Kárpátalja (Ukraine) | Ruthenian – 330,010 (54.5%) | 185,433 (30.6%) | German – 64,257 (10.6%) |

| Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia and Muraköz and part of Baranya (Croatia) | Croatian – 1,638,350 (62.3%) | 121,000 (3.5%) | Serbian – 644,955 (24.6%) German – 134,078 (5.1%) |

| Fiume (Croatia) | Italian – 24,212 (48.6%) | 6,493 (13%) | Croatian and Serbian – 13,351 (26.8%) Slovene – 2,336 (4.7%) German – 2,315 (4.6%) |

| Őrvidék (Burgenland, Austria) | German – 217,072 (74.4%) | 26,225 (9%) | Croatian – 43,633 (15%) |

| Muravidék (Prekmurje, Slovenia) | Slovene – 74,199 (80.4%) – in 1921 | 14,065 (15.2%) – in 1921 | German – 2,540 (2.8%) – in 1921 |

Hungarians outside the newly defined borders

The territories of the former Hungarian Kingdom that were ceded by the treaty to neighbouring countries in total (and each of them separately) had a majority of non-Hungarian nationals; however, the Hungarian ethnic area was much larger than the newly established territory of Hungary,[110] therefore 30% of the ethnic Hungarians were under foreign authority.[111]

After the treaty, the percentage and the absolute number of all Hungarian populations outside of Hungary decreased in the next decades (although, some of these populations also recorded temporary increase of the absolute population number). There are several reasons for this population decrease, some of which were spontaneous assimilation and certain state policies, like Slovakization, Romanianization, Serbianisation. Other important factors were the Hungarian migration from the neighbouring states to Hungary or to some western countries as well as decreased birth rate of Hungarian populations. According to the National Office for Refugees, the number of Hungarians who immigrated to Hungary from neighbouring countries was about 350,000 between 1918 and 1924.[112]

Minorities in post-Trianon Hungary

On the other hand, a considerable number of other nationalities remained within the frontiers of the independent Hungary:

According to the 1920 census 10.4% of the population spoke one of the minority languages as mother language:

- 551,212 German (6.9%)

- 141,882 Slovak (1.8%)

- 36,858 Croatian (0.5%)

- 23,760 Romanian (0.3%)

- 23,228 Bunjevac and Šokac (0.3%)

- 17,131 Serbian (0.2%)

- 7,000 Slovene (0.08%)

The percentage and the absolute number of all non-Hungarian nationalities decreased in the next decades, although the total population of the country increased. Bilingualism was also disappearing. The main reasons of this process were both spontaneous assimilation and the deliberate Magyarization policy of the state. Minorities made up 8% of the total population in 1930 and 7% in 1941 (on the post-Trianon territory).

After World War II approximately 200,000 Germans were deported to Germany, according to the decree of the Potsdam Conference. Under the forced exchange of population between Czechoslovakia and Hungary, approximately 73,000 Slovaks left Hungary and according to different estimations 120,500[99][113] or 45,000[114] Hungarians moved to present day Hungarian territory from Czechoslovakia. After these population movements, Hungary became a nearly ethnically homogeneous country.

Political consequences

Officially the treaty was intended to be a confirmation of the right of self-determination for nations and of the concept of nation-states replacing the old multinational Austro-Hungarian empire. Although the treaty addressed some nationality issues, it also sparked some new ones.[94]

The minority ethnic groups of the pre-war kingdom were the major beneficiaries. The Allies had explicitly committed themselves to the causes of the minority peoples of Austria-Hungary late in World War I. For all intents and purposes, the death knell of the Austro-Hungarian empire sounded on 14 October 1918, when United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing informed Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister István Burián that autonomy for the nationalities was no longer enough. Accordingly, the Allies assumed without question that the minority ethnic groups of the pre-war kingdom wanted to leave Hungary. The Romanians joined their ethnic brethren in Romania, while the Slovaks, Serbs and Croats helped establish states of their own (Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia). However, these new or enlarged countries also absorbed large slices of territory with a majority of ethnic Hungarians or Hungarian speaking population. As a result, as many as a third of Hungarian language-speakers found themselves outside the borders of the post-Trianon Hungary.[115]

While the territories that were now outside Hungary's borders had non-Hungarian majorities overall, there also existed some sizeable areas with a majority of Hungarians, largely near the newly defined borders. Over the last century, concerns have occasionally been raised about the treatment of these ethnic Hungarian communities in the neighbouring states.[116][117][118] Areas with significant Hungarian populations included the Székely Land[119] in eastern Transylvania, the area along the newly defined Romanian-Hungarian border (cities of Arad, Oradea), the area north of the newly defined Czechoslovak–Hungarian border (Komárno, Csallóköz), southern parts of Subcarpathia and northern parts of Vojvodina.

The Allies rejected the idea of plebiscites in the disputed areas with the exception of the city of Sopron, which voted in favour of Hungary. The Allies were indifferent as to the exact line of the newly defined border between Austria and Hungary. Furthermore, ethnically diverse Transylvania, with an overall Romanian majority (53.8% – 1910 census data or 57.1% – 1919 census data or 57.3% – 1920 census data), was treated as a single entity at the peace negotiations and was assigned in its entirety to Romania. The option of partition along ethnic lines as an alternative was rejected.[120]

Another reason why the victorious Allies decided to dissolve the Austria-Hungary was to prevent Germany from acquiring substantial influence in the future, since Austria-Hungary was a strong German supporter and fast developing region.[121] The Western powers' main priority was to prevent a resurgence of the German Reich, and they therefore decided that her allies in the region should be "contained" by a ring of states friendly to the Allies, each of which would be bigger than either Austria or Hungary.[122] Compared to the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary, post-Trianon Hungary had 60% less population, and its political and economic footprint in the region was significantly reduced. Hungary lost connection to strategic military and economic infrastructure because of the concentric layout of the railway and road network, which the borders bisected. In addition, the structure of its economy collapsed because it had relied on other parts of the pre-war kingdom. The country lost access to the Mediterranean and to the important sea port of Rijeka (Fiume) and became landlocked, which had a negative effect on sea trading and strategic naval operations. Many trading routes that went through the newly defined borders from various parts of the pre-war kingdom were abandoned.

With regard to the ethnic issues, the Western powers were aware of the problem posed by the presence of so many Hungarians (and Germans) living outside the newly formed states of Hungary and Austria. The Romanian delegation to Versailles feared in 1919 that the Allies were beginning to favour the partition of Transylvania along ethnic lines to reduce the potential exodus, and Prime Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu even summoned British-born Queen Marie to France to strengthen their case. The Romanians had suffered a higher relative casualty rate in the war than either Britain[123][124][125] or France[124][125][126] so it was considered that the Western powers had a moral debt to repay. In absolute terms, Romanian troops had considerably fewer casualties than either Britain or France, however.[125] The underlying reason for the decision was a secret pact between The Entente and Romania.[127] In the Treaty of Bucharest (1916) Romania was promised Transylvania and some other territories to the east of river Tisza, provided that she attacked Austria-Hungary from the south-east, where defences were weak. However, after the Central Powers had noticed the military manoeuvre, the attempt was quickly choked off and Bucharest fell in the same year.

By the time the victorious Allies arrived in France, the treaty was already settled, which made the outcome inevitable. At the heart of the dispute lay fundamentally different views on the nature of the Hungarian presence in the disputed territories. For Hungarians, the outer territories were not seen as colonial territories but rather part of the core national territory.[128] The non-Hungarians that lived in the Pannonian Basin saw the Hungarians as colonial-style rulers who had oppressed the Slavs and Romanians since 1848, when they introduced laws that the language used in education and in local offices was to be Hungarian.[129] For non-Hungarians from the Pannonian Basin it was a process of decolonisation instead of a punitive dismemberment (as was seen by the Hungarians).[130] The Hungarians did not see it this way because the newly defined borders did not fully respect territorial distribution of ethnic groups,[131] with areas where there were Hungarian majorities[131] outside the new borders. The French sided with their allies the Romanians who had a long policy of cultural ties to France since the country broke from the Ottoman Empire (partly because of the relative ease at which Romanians could learn French)[132] although Clemenceau personally detested Brătianu.[130] President Wilson initially supported the outline of a border that would have more respect to ethnic distribution of population based on the Coolidge Report, led by Archibald Cary Coolidge, a Harvard professor, but later gave in because of changing international politics and as a courtesy to other allies.[133]

For Hungarian public opinion, the fact that almost three-fourths of the pre-war kingdom's territory and a significant number of ethnic Hungarians were assigned to neighbouring countries triggered considerable bitterness. Most Hungarians preferred to maintain the territorial integrity of the pre-war kingdom. The Hungarian politicians claimed that they were ready to give the non-Hungarian ethnicities a great deal of autonomy. Most Hungarians regarded the treaty as an insult to the nation's honour. The Hungarian political attitude towards Trianon was summed up in the phrases Nem, nem, soha! ("No, no, never!") and Mindent vissza! ("Return everything!" or "Everything back!").[134] The perceived humiliation of the treaty became a dominant theme in inter-war Hungarian politics, analogous with the German reaction to the Treaty of Versailles.

By the arbitrations of Germany and Italy, Hungary expanded its borders towards neighbouring countries before and during World War II. This started by the First Vienna Award, then was continued with the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1939 (annexation of the remainder of Carpathian Ruthenia and a small strip from eastern Slovakia), afterwards by the Second Vienna Award in 1940, and finally by the annexations of territories after the breakup of Yugoslavia. This territorial expansion was short-lived, since the post-war Hungarian boundaries in the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947 were nearly identical to those of 1920 (with three villages – Horvátjárfalu, Oroszvár, and Dunacsún – transferred to Czechoslovakia).[87]

Legacy

Francesco Saverio Nitti served as Prime Minister of Italy between 1919 and 1920. Italy was a member of the Entente and participated in the treaty, he wrote in the Peaceless Europe[135] in 1922:

Hungary has undergone the greatest occupation of her territories and her wealth. This poor great country, which saved both civilization and Christianity, has been treated with a bitterness which nothing can explain except the desire of greed of those surrounding her, and the fact that the weaker people, seeing the stronger overcome, wish and insist that she shall be reduced to impotence. Nothing, in fact, can justify the measures of violence and the depredations committed in Magyar territory. What was the Rumanian occupation of Hungary: a systematic rapine and the systematic destruction for a long time hidden, and the stern reproach which Lloyd George addressed in London to the Premier of Rumania was perfectly justified. After the War everyone wanted some sacrifice from Hungary, and no one dared to say a word of peace or goodwill for her. When I tried it was too late. The victors hated Hungary for her proud defence. The adherents of Socialism do not love her because she had to resist, under more than difficult conditions, internal and external Bolshevism. The international financiers hate her because of the violences committed against the Jews. So Hungary suffers all the injustices without defence, all the miseries without help, and all the intrigues without resistance. Before the War Hungary had an area almost equal to that of Italy, 282,870 square kilometres, with a population of 18,264,533 inhabitants. The Treaty of Trianon reduced her territory to 91,114 kilometres -- that is, 32.3%. -- and the population to 7,481,954, or 41%. It was not sufficient to cut off from Hungary the populations which were not ethnically Magyar. Without any reason 1,084,447 Magyars have been handed over to Czeko-Slovakia, 457,597 to Jugo-Slavia, 1,704,851 to Rumania. Also other nuclei of population have been detached without reason.

In modern historiography

The treaty's perceived disproportion has had a lasting impact on Hungarian politics and culture, with some commentators even likening it to a "collective pathology" that places Trianon into a much larger narrative of Hungarian victimhood at the hands of foreign powers.[137] Within Hungary, Trianon is often referred to as a "diktat," "tragedy,"[138] and "trauma."[119] According to a study, two-thirds of Hungarians agreed in 2020 that parts of neighbouring countries should belong to them, the highest percentage in any NATO country.[139] Such irredentism was one of the main contributing factors to Hungary's decision to enter World War II as an Axis power; Adolf Hitler had promised to intervene on Hungary's behalf to restore majority-ethnic Hungarian lands lost after Trianon.

Hungarian bitterness at Trianon was also a source of regional tension after the Cold War ended in 1989.[128] For example, Hungary attracted international media attention in 1999 for passing the "status law" concerning estimated three-million ethnic Hungarian minorities in neighbouring Romania, Slovakia, Serbia and Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia and Ukraine. The law aimed to provide education, health benefits and employment rights to these minorities as a means of providing reparations for Trianon's negative consequences.[21][140]

Trianon's legacy is similarly implicated in the question of whether to grant extraterritorial ethnic Hungarians citizenship, an important issue in contemporary Hungarian politics. In 2004, a majority of voters approved extending citizenship to ethnic Hungarians in a referendum, which nonetheless failed due to low turnout.[141] In 2011, Viktor Orbán's newly formed government liberalized the nationality law by statute. Although Orbán depicted the new law as redressing Trianon, many commentators speculated about an additional political motivation; the law granted voting rights to extraterritorial Hungarians, who were seen as a reliable base of support for Orbán's national-conservative Fidesz party.[142][143]

Economic consequences

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was one economic unit with autarkic characteristics[144][145][146] during its golden age and therefore achieved rapid growth, especially in the early 20th century when GNP grew by 1.46%.[147] This level of growth compared very favourably to that of other European states such as Britain (1.00%), France (1.06%), and Germany (1.51%). There was also a division of labour present throughout the empire: that is, in the Austrian part of the monarchy manufacturing industries were highly advanced, while in the Kingdom of Hungary an agro-industrial economy had emerged. By the late 19th century, economic growth of the eastern regions consistently surpassed that of western, thus discrepancies eventually began to diminish. The key success of fast development was specialisation of each region in fields that they were best.

The Kingdom of Hungary was the main supplier of wheat, rye, barley and other various goods in the empire, and these comprised a large portion of the empire's exports.[148] Meanwhile, the territory of present-day Czech Republic (Kingdom of Bohemia) owned 75% of the whole industrial capacity of former Austria-Hungary.[149][150] This shows that the various parts of the former monarchy were economically interdependent. As a further illustration of this issue, post-Trianon Hungary produced 5 times more agricultural goods than it needed for itself,[151] and mills around Budapest (some of the largest ones in Europe at the time) operated at 20% capacity. As a consequence of the treaty, all the competitive industries of the former empire were compelled to close doors, as great capacity was met by negligible demand owing to economic barriers presented in the form of the newly defined borders.

Post-Trianon Hungary possessed 90% of the engineering and printing industry of the pre-war kingdom, while only 11% of timber and 16% of iron was retained. In addition, 61% of arable land, 74% of public roads, 65% of canals, 62% of railroads, 64% of hard surface roads, 83% of pig iron output, 55% of industrial plants, and 67% of credit and banking institutions of the former Kingdom of Hungary lay within the territory of Hungary's neighbours.[153][154][155] These statistics correspond to post-Trianon Hungary retaining only around a third of the kingdom's territory before the war and around 60% of its population.[156] The new borders also bisected transport links – in the Kingdom of Hungary the road and railway network had a radial structure, with Budapest in the centre. Many roads and railways, running along the newly defined borders and interlinking radial transport lines, ended up in different, highly introvert countries. Hence, much of the rail cargo traffic of the emergent states was virtually paralysed.[157] These factors all combined created some imbalances in the now separated economic regions of the former monarchy.

The disseminating economic problems had been also noted in the Coolidge Report as a serious potential aftermath of the treaty.[83] This opinion was not taken into account during the negotiations. Thus, the resulting uneasiness and despondency of one part of the concerned population was later one of the main antecedents of World War II. Unemployment levels in Austria, as well as in Hungary, were dangerously high, and industrial output dropped by 65%. What happened to Austria in industry happened to Hungary in agriculture where production of grain declined by more than 70%.[158][159] Austria, especially the imperial capital Vienna, was a leading investor of development projects throughout the empire with more than 2.2 billion crown capital. This sum sunk to a mere 8.6 million crowns after the treaty took effect and resulted in a starving of capital in other regions of the former empire.[160]

The disintegration of the multinational state conversely impacted neighbouring countries, too: In Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria a fifth to a third of the rural population could find no work, and industry was in no position to absorb them. In comparison, by 1921 the new Czechoslovak state reached 75% of its pre-war production owing to their favourable position among the victors and greater associated access to international rehabilitation resources.[161]

With the creation of customs barriers and fragmented protective economies, the economic growth and outlook in the region sharply declined,[162] ultimately culminating in a deep recession. It proved to be immensely challenging for the successor states to successfully transform their economies to adapt to the new circumstances. All the formal districts of Austria-Hungary used to rely on each other's exports for growth and welfare; by contrast, 5 years after the treaty, traffic of goods between the countries dropped to less than 5% of its former value. This could be attributed to the introduction of aggressive nationalistic policies by local political leaders.[163][164]

The drastic shift in economic climate forced the countries to re-evaluate their situation and to promote industries where they had fallen short. Austria and Czechoslovakia subsidised the mill, sugar and brewing industries, while Hungary attempted to increase the efficiency of iron, steel, glass and chemical industries.[144][165] The stated objective was that all countries should become self-sufficient. This tendency, however, led to uniform economies and competitive economic advantage of long well-established industries and research fields evaporated. The lack of specialisation adversely affected the whole Danube-Carpathian region and caused a distinct setback of growth and development compared to western and northern European regions as well as high financial vulnerability and instability.[166][167]

Miscellaneous consequences

Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia had to assume part of the financial obligations of the former Kingdom of Hungary on account of the parts of its former territory that were assigned under their sovereignty. Some conditions of the treaty were similar to those imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. After the war, the Austro-Hungarian navy, air force and army were disbanded. The army of post-Trianon Hungary was to be restricted to 35,000 men, and there was to be no conscription. Heavy artillery, tanks and air force were prohibited.[155] No railway was to be built with more than one track, because at that time railways held substantial strategic importance economically and militarily.[168]

Articles 54–60 of the treaty required Hungary to recognise various rights of national minorities within its borders.[169] Articles 61–66 state that all former citizens of the Kingdom of Hungary living outside the newly defined frontiers of Hungary were to ipso facto lose their Hungarian citizenship in one year.[170] Under articles 79 to 101 Hungary renounced all privileges of the former Austro-Hungarian monarchy in territories outside Europe, including Morocco, Egypt, Siam and China.[171]

See also

Notes

- The United States ended the war with the U.S.–Hungarian Peace Treaty (1921).

References

- "Magyarország népessége".

- "1910. ÉVI NÉPSZÁMLÁLÁS 1. A népesség főbb adatai községek és népesebb puszták, telepek szerint (1912) | Könyvtár | Hungaricana".

- "N psz ml l sok Erd ly ter let n 1850 s 1910 k z tt". www.bibl.u-szeged.hu. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019.

- A. J. P. Taylor, The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918, 1948.

- "Hungarian President János Áder's Speech on the Day of National Unity". Consulate General of Hungary Manchester.

- Dr. Dobó, Attila; Kollár, Ferenc; Zsoldos, Sándor; Kohári, Nándor (2021). A trianoni békediktátum [The Peace Dictate of Trianon] (PDF) (in Hungarian) (2nd ed.). Magyar Kultúra Emlékívek Kiadó. ISBN 978-615-81078-9-1.

- Prof. Dr. Gulyás, László (2021). Trianoni kiskáté - 101 kérdés és 101 válasz a békediktátumról (in Hungarian).

- Makkai, Béla (2019). "Chopping Hungary Up by the 1920 Peace Dictate of Trianon. Causes, Events and Consequences". Polgári Szemle: Gazdasági És Társadalmi Folyóirat. 15 (Spec): 204–225.

- Gulyás, László; Anka, László; Arday, Lajos; Csüllög, Gábor; Gecse, Géza; Hajdú, Zoltán; Hamerli, Petra; Heka, László; Jeszenszky, Géza; Kaposi, Zoltán; Kolontári, Attila; Köő, Artúr; Kurdi, Krisztina; Ligeti, Dávid; Majoros, István; Maruzsa, Zoltán; Miklós, Péter; Nánay, Mihály; Olasz, Lajos; Ördögh, Tibor; Pelles, Márton; Popély, Gyula; Sokcsevits, Dénes; Suba, János; Szávai, Ferenc; Tefner, Zoltán; Tóth, Andrej; Tóth, Imre; Vincze, Gábor; Vizi, László Tamás (2019–2020). A trianoni békediktátum története hét kötetben - I. kötet: Trianon Nagy Háború alatti előzményei, az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia bukása 1914-1918 / II. kötet: A katonai megszállástól a magyar békedelegáció elutazásáig 1918-1920 / III. kötet: Apponyi beszédétől a Határkijelölő Bizottságok munkájának befejezéséig / IV. kötet: Térképek a trianoni békediktátum történetéhez / V. kötet: Párhuzamos Trianonok, a Párizs környéki békék: Versailles, Saint-Germain, Neuilly, Sevres, Lausanne / VI. kötet: Dokumentumok, források / VII. kötet: Kronológia és életrajzok [The history of the Peace Dictate of Trianon in seven volumes - Volume I: Trianon's history during the Great War, the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy 1914-1918 / Volume II: From the military occupation to the departure of the Hungarian peace delegation 1918-1920 / Volume III: From Apponyi's speech to the completion of the work of the Boundary Demarcation Committees / Volume IV: Maps for the history of the Trianon peace decree / Volume V: Parallel Trianons, the peaces around Paris: Versailles, Saint-Germain, Neuilly, Sevres, Lausanne / Volume VI: Documents, sources / Volume VII: Chronology and biographies] (in Hungarian). Egyesület Közép-Európa Kutatására. ISBN 9786158046299.

- Bank, Barbara; Kovács, Attila Zoltán (2022). Trianon - A diktátum teljes szövege [Trianon - Full text of the dictate] (in Hungarian). Erdélyi Szalon. ISBN 9786156502247.

- Raffay, Ernő; Szabó, Pál Csaba. A Trianoni diktátum története és következményei [The history and consequences of the Dictate of Trianon] (in Hungarian). Trianon Múzeum.

- Craig, G. A. (1966). Europe since 1914. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Grenville, J. A. S. (1974). The Major International Treaties 1914–1973. A history and guides with texts. Methnen London.

- Lichtheim, G. (1974). Europe in the Twentieth Century. New York: Praeger.

- "Text of the Treaty, Treaty of Peace Between The Allied and Associated Powers and Hungary And Protocol and Declaration, Signed at Trianon June 4, 1920".

- "Open-Site:Hungary".

- Frucht 2004, p. 360.

- "Trianon, Treaty of". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2009.

- Macartney, C. A. (1937). Hungary and her successors: The Treaty of Trianon and Its Consequences 1919–1937. Oxford University Press.

- Bernstein, Richard (9 August 2003). "East on the Danube: Hungary's Tragic Century". The New York Times.

- Toomey, Michael (2018). "History, Nationalism and Democracy: Myth and Narrative in Viktor Orbán's 'Illiberal Hungary'". New Perspectives. 26 (1): 87–108. doi:10.1177/2336825x1802600110. S2CID 158970490.

- van den Heuvel, Martin P.; Siccama, J. G. (1992). The Disintegration of Yugoslavia. Rodopi. p. 126. ISBN 90-5183-349-0.

- Tucker & Roberts 2005, p. 1183: "Virtually the entire population of what remained of Hungary regarded the Treaty of Trianon as manifestly unfair, and agitation for revision began immediately."

- Botlik, József (June 2008). "AZ ŐRVIDÉKI (BURGENLANDI) MAGYARSÁG SORSA". vasiszemle.hu. VASI SZEMLE.

- "Szlovákiai Magyar Adatbank » pozsonyi hídfő". adatbank.sk.

- Richard C. Hall (2014). War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia. ABC-CLIO. p. 309. ISBN 9781610690317.

- Irredentist and National Questions in Central Europe, 1913–1939: Hungary, 2v, Volume 5, Part 1 of Irredentist and National Questions in Central Europe, 1913–1939 Seeds of conflict. Kraus Reprint. 1973. p. 69.

- Tucker & Roberts 2005, pp. xxv, 9.

- Tucker & Roberts 2005, p. 1078.

- Wiest, Andrew (2012) The Western Front 1917–1918: From Vimy Ridge to Amiens and the Armistice. Amber. pp. 126, 168, 200. ISBN 1906626138

- Tucker & Roberts 2005, p. 429.

- Fourteen Points Speech. Wikisource.

- Pastor, Peter (1 September 2014). "The United States' Role in the Shaping of the Peace Treaty of Trianon". The Historian. 76 (3): 550–566. doi:10.1111/hisn.12047. JSTOR 24456554. S2CID 143278311.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2011). World War One: The Global Revolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-0521736268.

- Keegan, John (1998). The First World War. p. 442. ISBN 0-09-180178-8.

- Paxton, Robert; Hessler, Julie (2011). Europe in the Twentieth Century. CEngage Learning. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-495-91319-1.

- Cornelius, Deborah S. (2011). Hungary in World War II: Caught in the Cauldron. Fordham University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8232-3343-4.

- Kitchen, Martin (2014). Europe Between the Wars. Routledge. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-317-86753-1.

- Romsics, Ignác (2002). Dismantling of Historic Hungary: The Peace Treaty of Trianon, 1920 Issue 3 of CHSP Hungarian authors series East European monographs. Social Science Monographs. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-88033-505-8.

- Dixon J. C. Defeat and Disarmament, Allied Diplomacy and Politics of Military Affairs in Austria, 1918–1922. Associated University Presses 1986. p. 34.

- Sharp A. The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking after the First World War, 1919–1923. Palgrave Macmillan 2008. p. 156. ISBN 9781137069689.

- Severin, Adrian; Gherman, Sabin; Lipcsey, Ildiko (2006). Romania and Transylvania in the 20th Century. Corvinus Publications. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-882785-15-5.

- Szijj, Jolán (1996–2000). "Ország hadsereg nélkül (1918)" [A Country Without an Army (1918)]. In Kollega Tarsoly, István; Bekény, István; Dányi, Dezső; Hernádi, László Mihály; Illésfalvi, Péter; Károly, István (eds.). Magyarország a XX. században - I. Kötet: Politika és társadalom, hadtörténet, jogalkotás - II. Honvédelem és hadügyek [Hungary in the XX. century - Volume I: Politics and Society, Military history, Legislation - II. National Defense and Military Affairs] (in Hungarian). Vol. 1. Szekszárd: Babits Kiadó. ISBN 963-9015-08-3.

- Tarján M., Tamás. "A belgrádi fegyverszünet megkötése - 1918. november 13" [The Belgrade Armistice - 13 November 1918]. Rubicon (Hungarian Historical Information Dissemination) (in Hungarian).

- "WW1 and the First Hungarian Republic - Political and Military Situation before the Foundation of the Communist Party". Scholarly Community Encyclopedia. 9 June 2023.

- Agárdy, Csaba (6 June 2016). "Trianon volt az utolsó csepp - A Magyar Királyság sorsa már jóval a békeszerződés aláírása előtt eldőlt". VEOL - Veszprém Vármegye Hírportál.

- Fassbender, Bardo; Peters, Anne; Peter, Simone; Högger, Daniel (2012). The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law. Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-959975-2.

- "Armistice with Austria-Hungary" (PDF). Library of Congress. US Congress.

- Convention (PDF), 11 November 1918, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2018

- Agárdy, Csaba (6 June 2016). "Trianon volt az utolsó csepp – A Magyar Királyság sorsa már jóval a békeszerződés aláírása előtt eldőlt". veol.hu. Mediaworks Hungary Zrt.

- "Military arrangements with Hungary" (PDF). Library of Congress. US Congress.

- Naval War College (U.S.) (1922). International Law Studies. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 187.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Krizman, B. (1970). "The Belgrade Armistice of 13 November 1918". The Slavonic and East European Review. 48 (110): 67–87. JSTOR 4206164. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012.

- Roberts, P. M. (1929). World War I: A Student Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 1824. ISBN 978-1-85109-879-8.

- Breit, J. (1929) "Hungarian Revolutionary Movements of 1918–19 and the History of the Red War" in Main Events of the Károlyi Era. Budapest. pp. 115–116.

- Sachar, H. M. (2007) Dreamland: Europeans and Jews in the Aftermath of the Great War. Knopf Doubleday. p. 409. ISBN 9780307425676.

- Tucker S. World War I: the Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection ABC-CLIO 2014. p. 867. ISBN 9781851099658.

- Dowling, Timothy C. (2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 447. ISBN 978-1-59884-948-6.

- Andelman, D. A. (2009) A Shattered Peace: Versailles 1919 and the Price We Pay Today. John Wiley and Sons. p. 193 ISBN 9780470564721.

- Swanson, John C. (2017). Tangible Belonging: Negotiating Germanness in Twentieth-Century Hungary. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8229-8199-2.

- Aliaksandr Piahanau, ‘Each Wagon of Coal Should Be Paid for with Territorial concessions.’ Hungary, Czechoslovakia,and the Coal Shortage in 1918–21, Diplomacy & Statecraft 34/1 (2023): 86-116

- Okey, Robin (2003). Eastern Europe 1740–1985: Feudalism to Communism. Routledge. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-134-88687-6.

- Lukacs, John (1990). Budapest 1900: A Historical Portrait of a City and Its Culture. Grove Press. p. 2012. ISBN 978-0-8021-3250-5.

- Eötvös Loránd University (1979). Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestinensis de Rolando Eötvös Nominatae, Sectio philosophica et sociologica. Vol. 13–15. Universita. p. 141.

- Goldstone, Jack A. (2015). The Encyclopedia of Political Revolutions. Routledge. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-135-93758-4.

- Pastor, Peter (1988). Revolutions and Interventions in Hungary and Its Neighbor States, 1918–1919. Vol. 20. Social Science Monographs. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-88033-137-1.

- Sugar, Peter F.; Hanák, Péter; Frank, Tibor (1994). A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-253-20867-5.

- Hanák, Peter (1992) "Hungary on a fixed course: An outline of Hungarian history, 1918–1945." in Joseph Held, ed., Columbia history of Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. p. 168. ISBN 9780231076975

- Zeidler, Miklós (2018). A Magyar Békeküldöttség naplója [Diary of the Hungarian Peace Delegation] (in Hungarian). Budapest, MTA: MTA Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont Történettudományi Intézet (Historical Sciences Institute, Social Sciences Research Centre, Hungarian Academy of Sciences).

- "Grand Trianon in Versailles Palace. Facts". Paris Digest. 2019.

- "The Paris Peace Conference, 1919". Office of the Historian. US Department of State.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Ciobanu, Vasile (11 December 2010). "1918-1919 az erdélyi szász elit politikai diskurzusában - a Transindex.ro portálról". transindex.ro. Transindex.

- Kurti, Laszlo (2014) The Remote Borderland: Transylvania in the Hungarian Imagination. SUNY Press.

- "Povijest saborovanja" [History of parliamentarism] (in Croatian). Sabor. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007.

- "Constitution of Union between Croatia-Slavonia and Hungary". H-net.org.

- "Wide anarchy in Austria" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 November 1918.

- "Hrvatski sabor". Sabor.hr.

- Vuk, Ivan (2019). "Pripojenje Međimurja Kraljevstvu Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca: Od neuspjeloga pokušaja 13. studenog do uspješnoga zaposjedanja Međimurja 24. prosinca 1918. godine" [The Annexation of Međimurje to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes: From the unsuccessful attempt on 13 November to the successful occupation of Međimurje on 24 December 1918]. Časopis za suvremenu povijest (in Croatian). Zagreb: Croatian Institute of History. 51 (2): 520–527. doi:10.22586/csp.v51i2.8927. ISSN 0590-9597. S2CID 204456373.

- "Die Ereignisse in der Slovakei", Der Demokrat (morning edition), 4 June 1919.

- "Die italienisch-ungarische Freundschaft", Bohemia, 29 June 1919.

- Mayer, Arno J. (1967). Politics and Diplomacy of Peacemaking. Containment and Counterrevolution at Versailles, 1918–1919. New York: Knopf. p. 369

- David Hunter Miller, XVIII, 496.

- Deak 1942, p. 45.

- Miller, Vol. IV, 209. Document 246. "Outline of Tentative Report and Recommendations Prepared by the Intelligence Section, in Accordance with Instructions, for the President and the Plenipotentiaries 21 January 1919."

- Miller. IV. 234., 245.

- Történelmi világatlasz [World Atlas of History] (in Hungarian). Cartographia. 1998. ISBN 963-352-519-5.

- Pastor, Peter (2019). "Hungarian And Soviet Efforts To Possess Ruthenia, 1938–1945". The Historian. 81 (3): 398–425. doi:10.1111/hisn.13198. JSTOR 4147480. S2CID 203058531.

- Michálek, Slavomír (1999). Diplomat Štefan Osuský (in Slovak). Bratislava: Veda. ISBN 80-224-0565-5.

- "Prague Congress of Oppressed nations, Details that Austrian censor suppressed – Text of revolutionary proclamation". The New York Times. 23 August 1918. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- "Teleki Pál – egy ellentmondásos életút". National Geographic Hungary (in Hungarian). 18 February 2004. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- "A kartográfia története" (in Hungarian). Babits Publishing Company. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- Spatiul istoric si etnic romanesc. Editura Militara, Bucuresti. 1992

- "Browse Hungary's detailed ethnographic map made for the Treaty of Trianon online". dailynewshungary.com. 9 May 2017.

- Menyhért, Anna (2016). "The Image of the "Maimed Hungary" in 20th-Century Cultural Memory and the 21st Century Consequences of an Unresolved Collective Trauma". Environment, Space, Place. 8 (2): 69–97. doi:10.5840/esplace20168211.

- Józsa Hévizi (2004): Autonomies in Hungary and Europe, A COMPARATIVE STUDY, The Regional and Ecclesiastic Autonomy of the Minorities and Nationality Groups

- Frucht 2004, p. 356.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1976) The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918. Univ of Chicago Press.

- Kocsis & Kocsis-Hodosi 1998, p. 116.

- Kocsis & Kocsis-Hodosi 1998, p. 57.

- Brass 1985, p. 156.

- Brass 1985, p. 132.

- Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (2011). Slovakia in History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6.

- Murad, Anatol (1968). Franz Joseph I of Austria and his Empire. New York: Twayne Publishers. p. 20.

- Seton-Watson, Robert William (1933). "The Problem of Treaty Revision and the Hungarian Frontiers". International Affairs. 12 (4): 481–503. doi:10.2307/2603603. JSTOR 2603603.

- Slovenský náučný slovník, I. zväzok, Bratislava-Český Těšín, 1932.

- Kirk, Dudley (1969). Europe's Population in the Interwar Years. New York: Gordon and Bleach, Science Publishers. p. 226. ISBN 0-677-01560-7.

- Tapon, Francis (2012) The Hidden Europe: What Eastern Europeans Can Teach Us. Thomson Press India. p. 221. ISBN 9780976581222

- Molnar, Miklós (2001) A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge University Press. p. 262. ISBN 9780521667364

- Frucht 2004, pp. 359–360.

- Eberhardt, Piotr (2003) Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, and Analysis. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 290–299. ISBN 9780765618337

- Ra'anan, Uri (1991). State and Nation in Multi-ethnic Societies: The Breakup of Multinational States. Manchester University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7190-3711-5.

- Kocsis & Kocsis-Hodosi 1998, p. 19.

- Corni, Gustavo; Stark, Tamás (2008). Peoples on the Move: Population Transfers and Ethnic Cleansing Policies during World War II and its Aftermath. Berg. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-84520-480-8.

- Šutaj, Štefan (2007). "The Czechoslovak government policy and population exchange (A csehszlovák kormánypolitika és a lakosságcsere)". Slovak Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- Putz, Orsolya (2019) Metaphor and National Identity: Alternative conceptualization of the Treaty of Trianon. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- "Assaults on Minorities in Vojvodina". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- "Official Letter from Tom Lantos to Robert Fico" (PDF). Congress of the United States, Committee on Foreign affairs. 17 October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- "U.S. lawmaker blames Slovak government for ethnically motivated attacks on Hungarians". International Herald Tribune. 5 September 2006. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- Kulish, Nicholas (7 April 2008). "Kosovo's Actions Hearten a Hungarian Enclave". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- Győri, Róbert; Withers, Charles W. J. (2019). "Trianon and its aftermath: British geography and the 'dismemberment' of Hungary, c.1915-c.1922" (PDF). Scottish Geographical Journal. 135 (1–2): 68–97. doi:10.1080/14702541.2019.1668049. hdl:20.500.11820/322504e5-4f63-43ff-a5d7-f6528ba87a39. S2CID 204263956.

- Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste (1968) From Wilson to Roosevelt. Harper & Row Torchbooks

- Macmillan, Margaret (2003). Paris 1919: Six Months that Changed the World. Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50826-4.

- "Britain census 1911". Genealogy.about.com. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Present Day Romania census 1912 – population of Transylvania

- "World War I casualties". Kilidavid.com. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Clarey, Christopher. "France census 1911". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 4 June 2013.