Port-Christmas

Port-Christmas is a natural and historical site on the Kerguelen Islands, located at the northern tip of the main island, on the east coast of the Loranchet Peninsula. It covers the bottom of Baie de l'Oiseau, the first shelter for sailors approaching the archipelago from the north, and is easily identifiable by the presence at the entrance of a natural arch, now collapsed, known as the Kerguelen Arch.

Port-Christmas | |

|---|---|

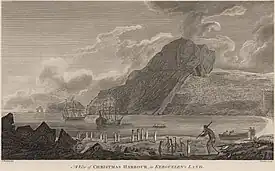

James Cook docking at Christmas Harbour in December 1776. The Kerguelen Arch is at left. (Engraving by John Webber, 1784) | |

Flag | |

Location of Port-Christmas within the Kerguelen Islands | |

| Coordinates: 48°40′41″S 69°1′15″E | |

| Country | France |

| Overseas territory | French Southern and Antarctic Lands |

| District | Kerguelen Islands |

| Named for | Yves Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec |

It was here, in 1774, that the explorer Yves Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec took possession of the island on behalf of King Louis XV of France. However, the name of the island, Christmas Harbour, was given by James Cook, whose ships anchored in the bay on Christmas Day back in 1776, during his third circumnavigation. The name appears in some French translations or fictional works such as le Havre de Noël or Port-Noël.

Considered to be a safe haven, in the 19th century it regularly welcomed the ships of seal and whale hunters, mainly from Nantucket, who scoured the southern seas and islands. The site is also occasionally used as a research station for geomagnetism investigations.

Descriptions of these landscapes by explorers in their travelogues inspired great writers, starting with Edgar Allan Poe (1838), followed by Jules Verne (1897), who incorporated them into their adventure novels, then Valery Larbaud (1933) and Jean-Paul Kaufmann (1993), among others, in their more personal works.

Toponymy

The name "Port-Christmas" was established by Raymond Rallier du Baty in 1908 to designate the most isolated part of Baie de l'Oiseau, as shown on the 1⁄228000 map published in 1922.[1] The Commission territoriale de toponymie des Terres australes françaises (TAAF Territorial Commission) upheld this designation when the 1⁄100000 IGN map was published in 1973.[2] It also extended the name to the area between the beach and Lake Rochegude, location to a secondary scientific station.[3]

This now-official toponymy puts an end to almost two centuries of debate between the name given to the whole bay by Kerguelen, "Baie de l'Oiseau", and the one chosen by Cook, "Christmas Harbour".

Indeed, during his second expedition, Yves Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec called this bay after L'Oiseau, the frigate he sent there in January 1774 to do reconnaissance.[1] Almost three years later, on December 25, 1776, the ships HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery anchored in the same location. Captain Cook, in command of the expedition, was well aware of the French navigator's earlier discovery, but was not yet aware of the details, nor that the bay had already been named.[4] He decided to celebrate the holiday's festivities by giving this "Christmas haven" the English name of Christmas Harbour.[5]

The predominantly Anglo-American presence of the archipelago in the 19th century, along with its literature, favored the use of the latter name.

However, when France decided to reaffirm its sovereignty by sending the French aviso ship l'Eure in 1893 to perform a new take-over ceremony, Baie de l'Oiseau formally reverted to its original name.

In the end, the current consensus, instituted by Rallier du Baty, which "semi-francizes" Christmas Harbour as Port-Christmas and reserves its denominations for a particular area of Baie de l'Oiseau, allows us to respect Kerguelen's former discovery while preserving the historical trace of Cook's passage.

Geography

Location

From the permanent base at Port-aux-Français, located 115 km to the southeast, Port-Christmas is one of the most isolated and inaccessible areas of the archipelago.[6] Given its distance and, in particular, its mountainous topography, the site is almost never reached by land. It can, however, be reached by sea after sailing at least 100 nautical miles (190 km). Baie de l'Oiseau, at the base of which the site is located, forms the first indentation at the northeastern end of the Loranchet peninsula. The bay is closed off to the north by the Cape-Haïtien and to the south by Kerguelen Arch.

Port-Christmas is towered over by Table de l'Oiseau (403 m) to the north and Mount Havergal (552 m) to the south.[7]

While most of the bay's shores are rocky and often steep, the bottom is occupied by a 350-meter-long black sand beach, formed by the erosion of the surrounding basalt rocks.[8] Here, a stream flows into the sea, after collecting both stormwaters from Mount Havergal and drainage tunnel waters from Lake Rochegude.[7] This lake, located approximately 500 m from the shore at an altitude of 40 m, marks the barrier separating Port-Christmas from Baie Ducheyron to the west.[9]

The anchorage at Port-Christmas is 11 meters deep[9] (6 fathoms). It offers a relatively safe haven[10] for sailors who frequent this particularly turbulent part of the ocean caused by the Roaring Forties.

Geology

The geological environment of Port-Christmas, like that of practically the entire Loranchet Peninsula, is dominated by trap-rocks, terraced basaltic piles formed by the superimposition of lava outpourings[11] around twenty-eight to twenty-nine million years ago.[12][13]

At various points in the bay, between the hard stratum, a few small coal seams[14] emerge. British explorer James Clark Ross noted this as early as 1840.[8] He also noted the presence of fossilized trees, the first of their kind to be spotted in the archipelago. These petrified woods, or simply lignites, found at Port-Christmas and Mount Havergal,[15] mainly belong to the conifer tree families known as Araucariaceae and Cupressaceae, more specifically the Araucarites, Cupressinoxylon, and Cupressoxylon genera, which are similar to those found today in the southernmost regions of the Southern Hemisphere. They bear witness to widespread ancient vegetation and past climates that were milder, or at least did not undergo intense glacial periods.[16]

Highlights

From Port-Christmas, the sight of the pillars of the Kerguelen Arch is a must. As soon as the archipelago was discovered, Kerguelen mentioned the imposing rocky arch located at the tip of the southern rim at the entrance to Baie de l'Oiseau. It rises to over 100 meters.[6] Named "le Portail" by Kerguelen, then "Arched-Rock" by James Cook, the arch collapsed between 1908 and 1913, leaving only its two basalt columns standing.[4]

Port-Christmas also has the geographical distinction of being one of the only land-based antipodes with the United States territory. It corresponds to Kevin, a township in Toole County, in the state of Montana, near the border with Canada.[17]

Natural environment

When the first navigators landed in the archipelago, they were struck by the abundance of a rich variety of birds. On the Port-Christmas shore itself, Kerguelen's lieutenants, like James Cook, noted the presence of "penguins".[5][18] A nesting colony of king penguins is still found there today, one of the smallest on Kerguelen with just forty breeders.[19] Elephant seals, known at the time as "sea lions", also frequent the beach.[5][18]

Fishing, on the other hand, was disappointing as the net Cook had thrown into the sea brought back only half a dozen fish.[5] Recent samples show that the fish in the area belong to the Channichthyidae family, or sometimes to the species Zanclorhynchus spinifer, the Antarctic horsefish, of the Congiopodidae family. The beach drop-offs at Port-Christmas are notable for their abundance of soft corals (Onogorgia nodosa), and the giant seaweed Macrocystis pyrifera forms dense seagrass meadow.[20]

Conversely, terrestrial vegetation is poorly developed. While early records describe a verdant, albeit short and treeless, coastal landscape covered with grasses (Gramineae), azorella, and Kerguelen cabbage, the colonization of the entire main island by rabbits has since led to a considerable weakening of plant formations, which are often reduced to a meager meadow of Acaena magellanica.[21]

Generally speaking, the fauna and flora are in accordance with that to be found in Baie de l'Oiseau and more widely on the main island of the archipelago, known as La Grande Terre.

The entire Port-Christmas area is part of the Réserve naturelle nationale des Terres australes françaises,[22] which, since 2019, has been classified as World Heritage under the name of "French Southern and Antarctic Lands".

Like the majority of the archipelago, its terrestrial sector benefits from the "classic" protection regime. The area is closed to the introduction of any new animal or plant, any disturbance of living communities, any industrial, commercial or mining activity, and any biological or mineral extraction, with the exception of rare exemptions that may be granted by the Reserve's management or for scientific research purposes. Access to the site is possible, but is regulated and subject to authorization.[23]

The marine section, like all the territorial waters of the Kerguelen Islands, is included in the "zone de protection renforcée marine". Any disturbance of the natural environment is prohibited, except for scientific activities duly approved by the authorities. All professional and recreational fishing is prohibited, with no exceptions.[23]

History

The first sighting of the islands dates back to the second expedition of Yves Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec, aboard the Roland, a 64-cannon vessel, with an escort of two smaller ships, l'Oiseau and la Dauphine. The expedition reached the coast of Grand-Terre [sic] on December 14, 1773,[24] but adverse weather conditions prevented them from disembarking. During the few days la Dauphine was separated from the group, Ferron du Quengo, commander of the Corvette, spotted the entrance to a bay around December 20th, 1773, but was unable to gain entry. On December 25, 1773, Kerguelen delegated to l'Oiseau and la Dauphine the task of trying to land there.[1] The commander of l'Oiseau, Monsieur de Rosnevet, mapped out the bay and named it Baie de l'Oiseau, after his frigate.[1] But it wasn't until January 6th, 1774, that he managed to send his lieutenant Henri Pascal de Rochegude ashore in a longboat. The latter attached a bottle to a prominent rock, containing a formal takeover statement:[1][5]

« Ludovico XV. galliarum rege, et d.[nb 1] de Boynes regi a Secretis ad res maritimas annis 1772 et 1773. »[nb 2]

The fact that the years 1772 and 1773 are mentioned, even though the official parchment was not issued until 1774, means that the land had already been discovered and that this formal takeover merely reiterated the first expedition by Kerguelen, who was led by Lieutenant Charles-Marc du Boisguéhenneuc on February 14, 1772, to "Baie du Lion-Marin" (now known as Anse du Gros Ventre), forty leagues to the south. James Cook, who stopped off in the archipelago on his "third voyage", dropped the anchors of his ships Discovery and Resolution on Christmas Day, 1776. He called the place Christmas Harbour and realized the previous presence of the French when he found the message they had left. He added a mention of his own berthing and a vintage silver coin, relocating the bottle under a cairn.[1][5] The British explorer notes the optimal anchorage and water provisioning conditions. The ship's surgeon, William Anderson, noted both the presence of Kerguelen cabbage (Pringlea antiscorbutica), which could be used to combat the scurvy[nb 3] often suffered by crews on long voyages, and the abundance of "oil resources".[nb 4][25] It was also from Christmas Harbour that Cook thought of naming the archipelago the "Islands of Desolation", before paying tribute to his first French discoverer by naming them after himself, albeit somewhat mischievously:[nb 5]

« I would have called them the Islands of Desolation, if I didn't want to deprive Monsieur de Kerguelen the honor of giving them his name. »

The expedition set off again on December 31 to explore the surrounding eastern coasts all the way to the present-day Gulf of Morbihan, which James Cook named "Royal Sound".

It only took a few years for the previously untouched Desolation Islands to become a coveted land. The first expedition to hunt marine mammals by American ships from the island of Nantucket was documented as early as 1792.[25] The interest of the Americans in undertaking campaigns in the southern seas was even greater, considering that the British had forbidden them to hunt in the northern hemisphere.[25] Christmas Harbour, with its safe anchorage,[10] became a popular stopover throughout the nineteenth century, as it was easy to reach, even if it didn't offer the best shelter in poor weather.[8] In the early 1820s, American explorer and sealing captain Benjamin Morrell (1795–1839) made it his main anchorage.[25][26] The Kerguelen archipelago was frequented by whalers and sealers until 1909 (with a highpoint between 1840 and 1870).[25]

In 1840, British explorer James Clark Ross anchored at Port-Christmas for 68 days, between May and July,[8] as part of a major scientific expedition around the world and towards the poles, with the primary objective of studying geomagnetism. Two temporary observatories were built at the far end of the bay, one dedicated to astronomical observations, and the other to the study of terrestrial magnetism. Every day, at a fixed time, regardless of the weather, magnetism readings were taken simultaneously with a complementary station located almost antipodally in Toronto, Canada.[6][8][27] Ross's mission brief included a long series of other physical observations to be carried out: meteorological, oceanographic, hydrographic, as well as a naturalistic component to which the expedition's surgeons, Robert McCormick, Joseph Dalton Hooker and David Lyall, made a major contribution by exploring from Christmas Harbour.

Since its discovery, despite numerous visits, the islands have never been permanently inhabited, particularly by the French, which exposes them to the possibility of dispossession by other countries. Around 1890, England and Australia began to lay claim to the Kerguelens.[6] Consequently, at the suggestion of the Boissière brothers, President Sadi Carnot decided to send the Eure, an aviso french ship under the captaincy of Commander Louis Édouard Paul Lieutard (1842–1902) [nb 6], to solemnly repossess the Austral Islands on behalf of France. The mission took place in the Kerguelen archipelago from January 1 to 15 1893, before moving on to Saint Paul Island and Amsterdam Island. On New Year's Day 1893, the Eure arrived at Port-Christmas, where the Francis Allyn, an American seal-hunting schooner under Captain Joseph J. Fuller, happened to be. The French military, reiterating the takeover made 120 years earlier on the same spot, proceeded ashore to raise the colors on the mast and affix a copper plaque engraved "EURE – 1893". Twenty-one cannon shots were fired. Over the following fifteen days, the same operations were repeated at various points around the archipelago.[28][29] The territory was now ready for the arrival of settlers. Six months later, Henry and René-Émile Bossière obtained an exclusive 50-year concession over the entire French Southern Territories.[6][25]

Returning from an oceanographic expedition to the outskirts of Antarctica, German marine biologist Carl Chun arrived in Port-Christmas aboard the Valdivia in 1898, where he declared himself fascinated by the "romanesque" character of the place.[6]

On March 9, 1908, Raymond Rallier du Baty and his brother Henri anchored their ketch, the J.B. Charcot, before embarking on a methodical exploration of the archipelago. To own a territory, it is essential to be fully acquainted with it and to officially designate its remarkable landmarks, especially with the economic development of Kerguelen in mind. To this effect, the du Baty brothers received moral and financial support from the Société de Géographie to carry out their reconnaissance and mapping work.[1][30]

During the 20th century, Port-Christmas was occasionally used as a site for scientific studies, but its remoteness was an obstacle to continuous monitoring. During the International Geophysical Year in 1957 and 1958, Port-aux-Français was chosen as the site for a permanent magnetic repeat station.[27][31] In December 1964, the replacement ship, the Gallieni,[32] brought a team to Port-aux-Français to carry out tellurometer measurements and helicopter overflights to produce a general map of the archipelago. This team set up camp in virtually the same location as Ross had chosen in 1840. Two Ferdinand Fillod-type metal cabins were erected in the hope of providing a permanent secondary station.[33] For several years, they were used as shelters for scientific teams during southern summer, but were eventually abandoned and destroyed,[34] and no longer appear on the TAAF or IPEV cabin lists.[19]

Given its historic character, the Port-Christmas site is one of several whose artifacts will be inventoried under the 2018–2027 Management Plan from the Réserve naturelle nationale des Terres australes françaises.[35]

Literature

Numerous writers, mainly novelists, have made mention of this place.

In 1838, the American writer Edgar Allan Poe was the first to publish "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket", translated into French in 1858 by Charles Baudelaire under the title Aventures d'Arthur Gordon Pym. In it, he describes the nearly one-month stay on Christmas Harbour in 1827 by the crew of the Jane Guy vessel, who rescued the two main protagonists. Poe accurately describes the natural harbor and the typical arch,[36] sometimes repeating almost verbatim[37] the description given by seal-hunting captain Benjamin Morrell in A Narrative of Four Voyages, published in 1832. In particular, the protagonist Arthur Pym cites Wasp Harbour, a toponym that only Morrell uses to designate his usual anchorage, which resembles Port-Christmas but whose description is too imprecise to be sure.[25]

Jules Verne, using Poe's novel as a theme and plot for his own, sets the first three chapters of An Antarctic Mystery (1897) set in the Desolation Islands, where his hero, the American mineralogist Joerling, spends from June to August 1839 in Christmas Harbour, before sailing south on the schooner Halbrane. Without ever having been there, the French novelist gives a precise geographical description and establishes a fictitious cosmopolitan settlement of around twenty inhabitants centered around Fenimore Atkins, the proprietor of the Au Cormoran-Vert inn, living off the seasonal staging of English and American sealers and whalers.[38] The two 19th-century novelists anchored Port-Christmas in the collective imagination as one of the gateways to the Deep South, the Southern Ocean and the Antarctic continent.

Navigator and travel writer Raymond Rallier du Baty docked at Port-Christmas in 1908 to map the archipelago and wrote a literary description in his story On peut aller loin avec des cœurs volontaires.[30]

In 1933, novelist and poet Valery Larbaud published Le gouverneur de Kerguelen (The Governor of Kerguelen), a short story that uses a disciplinary transfer to Port-Noël as a pretext to initiate the game of "ten essential books that one would take to a desert island" and establish a library.[39] He humorously proposes the following rules:

"... 'You have had the misfortune to displease those in high places; but in deference to your merits, we have contented ourselves with distancing you by appointing you for one ... three ... five years (that's a maximum) Governor of (sic) Kerguelen, with residence at Port-Noël, the main town of this colony. [...] You will only be able to take with you one... five... ten... twenty books, on condition that they are chosen by you from...'. Here, all suppositions are allowed..." – Valery Larbaud, 1933.

This little game is also the occasion for correspondence between Larbaud and the Dutch literary scholar Edgar du Perron, who proposes and discusses his own choices.[40]

Edgar Aubert de la Rüe, who visited the archipelago four times between 1928 and 1953 to carry out various geographical and geological studies, spending many months there in total, mentions Port-Christmas in his brief novel Deux ans aux Îles de la Désolation (1954).[41]

In 1993, journalist and writer Jean-Paul Kauffmann, in his story L'Arche des Kerguelen, made Port-Christmas the ultimate goal of a personal quest he undertook in the Kerguelen archipelago a few years after his release from three years' captivity as a hostage in Lebanon.[6] His entire book – which retells the history of the Kerguelen archipelago, its explorers and residents, as well as the details of his own several-week stay – focuses on reaching this mythical place, one of the most isolated in the archipelago and even one of the most inaccessible on Earth, which he never managed to reach despite various attempts by boat, on foot and by helicopter.[6]

French sailor Isabelle Autissier, after a dismasting in 1994 that forced her to make reparations in Port-aux-Français, published a literary biography in 2006, Kerguelen, le voyageur du pays de l'ombre, in which she describes in detail the arrival of the crew of L'Oiseau in the homonymous bay in January 1774, and the onshore takeover led by Messieurs de Rochegude and du Cheyron,[42] based on available historical data (diaries and accounts) and her own experience of the site. She gives the following description:

"Beyond the beach, they waded through a grassy swamp and climbed a mound. [...] No trees, no flowers, in the heart of that summer brightened by austerity. The sparse greenery was covered in patches of old snow. The overall atmosphere was sad and cold. Grandiose indeed, but in the manner of a funerary monument when the shine of smooth marble evokes eternity... " – Isabelle Autissier, 2006.

Philately

At least five TAAF stamps featuring the Port-Christmas location or its immediate surroundings were issued,[43][44] the first three engraved by Pierre Béquet :

- 1976: face value of 3.50 francs, commemorating the bicentenary of Cook's arrival in 1776 with a reproduction of the landing scene engraved in 1784 by John Webber;

- 1979: face value 2.70 francs, illustrating the arrival of explorer Ross at Christmas Harbour in 1840, with a reproduction of Samuel Williams' engraving of the HMS Terror passing in front of the Kerguelen Arch (Arched Rock);

- 1997: face value of 24 francs, celebrating the bicentenary of Admiral Kerguelen's death, with a depiction of "Le Hâvre [sic] de Noël", one of the French copies of John Webber's engraving;

- 2001: face value of 3 euros, depicting an actual view of the Kerguelen Arch, engraved from a photograph by Jacques Jubert;

- 2011: face value of 1.10 euros, depicting the EE Forbin at the Kerguelen arch during its visit to the archipelago from January 17 to 23 1978, stamp engraved by Elsa Catelin, issued jointly with Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.

Notes

- d. stands for Domino, according Cook

- in english: On behalf of Louis XV, King of France, and Monsieur de Boynes, Secretary of State of Maritime Affairs, in the years 1772 and 1773.

- as a source of vitamin C: this has yet to be identified, but studies have already shown the usefulness of certain fruits and vegetables (Traité sur le scorbut by James Lind in 1757).

- by melting the fat of elephant seals.

- According to Kauffmann 1993, pp. 105–106, this apocryphal formula must be attributed to Canon Douglas, James Cook's editor, who published the British navigator's account after Cook's death.

- The name of the mission leader, Lieutard, was given in 1963 by glaciologist Albert Bauer to a summit located south of the archipelago on the Rallier du Baty Peninsula. See Mont Lieutard archive

References

- Jean-René Vanney, Histoire des mers australes, Paris, Fayard editions, 1986, 737 p. (ISBN 2-213-01777-8)

- Dominique Delarue, "Historique toponymie : commission de Toponymie" [archive], on http://www.kerguelen-voyages.com Archived 2022-12-24 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 21, 2020)

- Commission territoriale de toponymie et Gracie Delépine (pref. Pierre Charles Rolland), Toponymie des Terres australes et antarctiques françaises, Paris, French Southern and Antarctic Territories, August 20th, 1973, 433 p. (read online Archived 2022-03-02 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine [PDF]) p.6 archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine and p. 275 archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- Gracie Delépine (pref. Christian Dors, senior administrator of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands), Les îles australes françaises : Kerguelen, Crozet, Amsterdam, Saint-Paul, Rennes, Éditions Ouest-France, October 1995, 213 p. (ISBN 2-7373-1889-0, chap. II ("Geography, landscapes"), pp. 31 and 37.

- (en) James Cook, The Three Voyages of Captain James Cook Round the World, vol. 5 : being the first of the third voyage, Londres, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, et Brown, 1821 (read online Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), chap. IV, p. 146–151

- Jean-Paul Kauffmann, L'Arche des Kerguelen : Voyage aux Îles de la Désolation, Paris, Flammarion editions, 1993, 249 p. (ISBN 2-08-066621-5)

- Amicale des missions australes et polaires françaises (AMAEPF), Zoom on IGN map 80354 of the Kerguelen Islands, Port-Christmas.

- (en) James Clark Ross, A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions – During the Years 1839–43, vol. 1, London, John Murray, 1847 (lire en ligne Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine)

- Carte de reconnaissance des îles Kerguelen – feuille nord-est Archived 2022-01-04 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine

- "Christmas-Harbour", in Dictionnaire géographique universel, A. J. Kilian and Ch. Piquet, 1826 (read online Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), p. 22

- André Giret et al, "L'archipel de Kerguelen, les plus vieilles îles dans le plus jeune océan", Géologues, n° 137, 2003, p. 15-23 (read online Archived 2023-03-29 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine)

- (en) P. Camps, B. Henry, K. Nicolaysen et G. Plenier, "Statistical properties of paleomagnetic directions in Kerguelen lava flows: implications for the late Oligocene paleomagnetic field", Journal of geophysical research, vol. 112, 2007, p. 6 (DOI 10.1029/2006JB004648 Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, read online Archived 2023-03-22 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 1st 2020)

- (en) K. Nicolaysen, F.A. Frey, K.V. Hodges, D. Weis et A. Giret, "40Ar/39Ar geochronology of flood basalts from the Kerguelen Archipelago, southern Indian Ocean: implications for Cenozoic eruption rates of the Kerguelen plume", Earth and Planetary Science Letters, vol. 174, nos 3–4, January 15th 2000, p. 313-328 (DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(99)00271-X Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Narrative of the wreck of the Favorite on the island of Desolation detailing the adventures, sufferings and privations of John Nunn", TAAF n° 28, Paris, La Documentation française, July–September 1964, p. 19 (read online Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 25th 2020)

- (de) Die Forschungsreise S.M.S. "Gazelle" in den Jahren 1874 bis 1876 unter Kommando des Kapitän zur See Freiherrn von Schleinitz : herausgegeben von dem Hydrographischen Amt des Reichs-Marine-Amts, vol. I : Der Reisebericht, Berlin, Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn, 1889, 307 p. (read online Archived 2023-06-05 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), chap. VII (" The Kerguelen Islands "), p. 120 (Christmas port).

- Marc Philippe, André Giret and Gregory J. Jordan, "Bois fossiles tertiaires et quaternaires de Kerguelen (océan Indien austral)" ["Tertiary and Quaternary fossil wood from Kerguelen (southern Indian Ocean)"], Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences, Paris, iIA – Earth and Planetary Science, June 1998 (read online archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 25th 2020).

- "48°40'41N, 111°59'45W (antipodal coordinates of Port-Christmas) "N%20111°59'45.0"W/@48.6780591,-112.135909,33425m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x0:0x0!8m2!3d48.6780556!4d-111.9958333 Archived 1998-11-30 at Wikiwix" , at https://www.google.fr/maps/ archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 20, 2020)

- Yves Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec, Relation de deux voyages dans les mers australes et des Indes, faits en 1771, 1772, 1773 et 1774, par M. de Kerguelen, Paris, Chez Knapen & sons, 1782, 247 p., In-8° (read online Archived 2022-01-04 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), p. 21-83.

- Réserve naturelle nationale des Terres australes françaises (downloadable document from the World Heritage website Archived 2022-11-27 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), Volet A du plan de gestion 2011–2015: diagnostic de la réserve, October 12th, 2010, 2058 p., p. 353.

- (en) Jean-Pierre Féral et al, "Long-term monitoring of coastal benthic habitats in the Kerguelen Islands: a legacy of decades of marine biology research", The Kerguelen Plateau: marine ecosystem and fisheries. Proceedings of the Second Symposium, Kingston, Tasmania, Australian Antarctic Division, 2019, pp. 383–402 (ISBN 978-1-876934-30-9, DOI 10.5281/zenodo.3249143 Archived 2022-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, read online Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 27th, 2020).

- Chef de district de Kerguelen (with the contribution of Clément Clasquin, officer in charge of "monitoring introduced mammals" at the Nature Reserve), "Les lapins de Kerguelen Archived 2023-06-09 at the Wayback Machine" archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, on Blog officiel du district de Kerguelen -TAAF, French Southern and Antarctic Territories, October 11th, 2019 (accessed March 27th, 2020).

- "Plan de gestion 2018–2027 de la Réserve naturelle nationale des Terres australes françaises – volet A" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- Decree n° 2006-1211 of October 3rd, 2006 creating the réserve naturelle des Terres australes françaises Archived 2023-04-09 at the Wayback Machine modified by decree n° 2016-1700 of December 12th, 2016 archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine

- François Pagès, Voyages autour du monde et vers les deux pôles, par terre et par mer : pendant les années 1767,1768,1769,1770,1771,1773,1774 & 1776, t. second, 1782, 272 p. (read online Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), "Vers le pôle du sud", p. 66.

- Gracie Delépine, Histoires extraordinaires et inconnues dans les mers australes, Ouest-France, coll. "Écrits", 2002, 230 p. (ISBN 2-7373-2961-2)

- (en) Benjamin Morrell, A Narrative of Four Voyages: to the South Sea, North and South Pacific Ocean, Chinese Sea, Ethiopic and Southern Atlantic Ocean, Indian and Antarctic Ocean from the year 1822 to 1831, New York, J. & J. Harper, 1832, 492 p. (read online Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), chap. IV, p. 62-63.

- Histoire des Observatoires magnétiques de l'EOST archive on the École et observatoire des sciences de la Terre website.

- Yann Libessart (pref. Isabelle Autissier), Les manchots de la République: Un an aux Kerguelen, Paris, Les petits matins, November 2009, 223 p. (ISBN 978-2-915879-54-4, online presentation archive), "Avant l'heure, c'est plus l'Eure", [originally published on July 7th 2008, in Libération, written on Y. Libessart's blog, Les manchots de la République]

- "Archipel des Kerguelen" archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, at https://www.institut-polaire.fr/ Archived 2021-06-17 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, Institut Polaire Français Paul-Émile-Victor (accessed March 20th, 2020).

- Raymond Rallier du Baty (trans. from English by Renaud Delcourt, pref. Benoît Heimermann), On peut aller loin avec des cœurs volontaires: Aventures aux Kerguelen [originally written in English as "15,000 Miles in a Ketch"], Paris, Le Livre de poche, coll. "La lettre et la plume", May 2nd 2012 (1st ed. 1917), 288 p. (ISBN 978-2-253-16365-7, online presentation Archived 2023-05-07 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine)

- Magnetic repetition stations associated with French austral observatories Archived 2022-03-08 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine on the École et observatoire des sciences de la Terre.

- Le Gallieni, futur-Eastern Rise Archived 2023-06-02 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, Messageries maritimes, accessed March 14th, 2020.

- Jacques Nougier, "Installation de la base secondaire de Port-Christmas : Baie de l'Oiseau – Archipel de Kerguelen", TAAF n° 32, Paris, La Documentation française, July–September 1965, p. 37-45 archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Dominique Delarue, "Port-Christmas" archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, on http://www.kerguelen-voyages.com Archived 2022-12-24 at the Wayback Machine [archive] (accessed March 30th, 2020)

- "Plan de gestion 2018–2027 de la Réserve naturelle nationale des Terres australes françaises – volet B (action FG32)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-06-15. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- Edgar Allan Poe (trans. Charles Baudelaire, pref. A. G. Pym), Aventures d'Arthur Gordon Pym de Nantucket ["The narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket"], Paris, Michel Lévy Frères, 1868, new ed. (1st ed. 1858), 277 pp. (read online Archived 2022-01-04 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), chap. XIV ("Albatrosses and penguins"), p. 172

- (en) The Continuing Puzzle of Arthur Gordon Pym – Some Notes and Queries Archived 2023-06-25 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine by J. V. Ridgely (Université Columbia), Poe Newsletter, June 1970, vol. III, n° 1, 3:5–6.

- Jules Verne (ill. George Roux), Le Sphinx des glaces, Paris, Bibliothèque d'éducation et de recréation J. Hetzel et cie, coll. "Hetzel / Voyages extraordinaires", November 22nd 1897, 447 pp. (read online Archived 2022-01-04 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), "I (Les îles Kerguelen), II (La schëlette Halbrane) and III (Le capitaine Len Guy)"

- Valery Larbaud (pref. Marcel Arland), Aux couleurs de Rome, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, coll. "Œuvres", 1957 (ISBN 978-2-07-010300-3), "Le Gouverneur de Kerguelen (short story originally published solo in 1933 by "Les amis d'Édouard")", pp. 1053–1062.

- Eddy du Perron à Valery Larbaud Archived 2022-08-14 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, Septentrion vol. 7, Rekkem, 1978.

- Edgar Aubert de la Rüe, Deux ans aux Îles de la Désolation, Sceaux, Julliard editions, 1954, In-16.

- Isabelle Autissier, Kerguelen: Le voyageur du pays de l'ombre, éditions Grasset & Fasquelle, March 2006, 306 p. (ISBN 978-2-246-67241-8, online version Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine), chap. 10, p. 244-247.

- Encyclopédie des tours du monde: Sur mer, sur terre et dans les airs Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, by Christian Nau, L'Harmattan Editions, 2012, (ISBN 9782296503601), p. 59.

- L'Arche Des Kerguelen Archived 2022-08-09 at the Wayback Machine archive Archived 2023-07-15 at the Wayback Machine on the website www.timbresponts.fr Archived 2023-06-13 at the Wayback Machine