Cataract surgery

Cataract surgery, which is also called lens replacement surgery, is the removal of the natural lens (also called the "crystalline lens") of the human eye that has developed a cataract, an opaque or cloudy area.[1] The eye's natural lens is usually replaced with an artificial intraocular lens (IOL).[2]

| Cataract surgery | |

|---|---|

Cataract surgery, using a temporal approach phacoemulsification probe (in right hand) and "chopper" (in left hand) | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| ICD-9-CM | 13.19 |

| MeSH | D002387 |

| MedlinePlus | 002957 |

Over time, metabolic changes of the crystalline lens fibres lead to the development of a cataract, causing impairment or loss of vision. Some infants are born with congenital cataracts, and environmental factors may lead to cataract formation. Early symptoms may include strong glare from lights and small light sources at night, and reduced visual acuity at low light levels.[3][4]

During cataract surgery, the cloudy natural lens is removed, either by emulsification in place or by cutting it out.[2] An IOL is usually implanted in its place to restore useful focus. Cataract surgery is generally performed by an ophthalmologist in an out-patient setting at a surgical centre or hospital. Local anaesthesia is normally used; the procedure is usually quick, and causes little or no pain and minor discomfort to the patient. Recovery sufficient for most daily activities usually takes place in days and full recovery about a month.[5]

Well over 90% of operations are successful in restoring useful vision, and there is a low complication rate. Day care, high-volume, minimally invasive, small-incision phacoemulsification with quick post-operative recovery has become the standard of care in cataract surgery in the developed world.[2] Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS), which is considerably more economical in time, capital equipment, and consumables, but provides comparable results, is popular in the developing world.[6] Both procedures have a low risk of serious complications.[7][8]

Description

Cataract surgery, also called lens replacement surgery, is the removal of the natural lens (also called the "crystalline lens") of the human eye that has developed a cataract, an opaque or cloudy area.[1] The eye's natural lens is usually replaced with an artificial intraocular lens (IOL) to restore focus within a useful range of distances.[2] It is the definitive treatment for vision impairment due to lens opacification.[9]

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that causes visual impairment.[4][10] Cataracts usually develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes.[4] Symptoms may include faded colours, blurred or double vision, halos around lights, sensitivity to glare from bright lights, and night blindness.[4] This may result in difficulty driving, reading, or recognizing faces.[11] Poor vision caused by cataracts may also increase the risk of falling and depression.[12]

Cataracts most commonly occur due to aging, but may also be caused by trauma or radiation exposure, be present since birth, or may represent a complication of eye surgery aimed to solve other health problems.[4][13] Risk factors include diabetes, longstanding use of corticosteroid medication, tobacco smoking, extended hyperbaric oxygen therapy, prolonged exposure to sunlight, and consumption of alcohol.[4] Cataracts form when clumps of proteins or yellow-brown pigment accumulate in the lens, which reduces transmission of light to the retina at the back of the eye.[4] Cataracts can be diagnosed via an eye examination.[4]

Early symptoms of cataract may be improved by wearing specific types of glasses; if this does not help, cataract surgery is the only effective treatment.[4] Surgery with implants generally results in better vision and an improved quality of life: however, the procedure is not readily available in many countries.[4][13][14][15]

About 20 million people worldwide are blind due to cataracts,[13] which cause 51% of all cases of blindness and 33% of visual impairment.[16][17] They are the cause of approximately 5% of all cases of blindness in the United States, and nearly 60% of all cases in parts of Africa and South America.[15] Blindness from cataracts occurs in between 10 and 40 children per 100,000 in the developing world, and between 1 and 4 children per 100,000 in the developed world.[10] Cataracts become more common with age.[4] In the United States, cataracts occur in 68% of those over the age of 80 years.[18] They are more common in women, and less common in Hispanic and Black people.[18]

Contraindications

Contraindications to cataract surgery include cataracts that do not cause visual impairment and medical conditions that predict a high risk of unsatisfactory surgical outcomes.[2]

The usefulness and effectiveness of the implantation of a posterior chamber intraocular lens (PCIOL) in infants younger than seven months have been disputed, as eye growth in infants is rapid and unpredictable; for this reason, an early implant is likely to result in large refractive error later in childhood.[19] Congenital cataracts may be caused by factors that make the eye more susceptible to an excessive amount of inflammation, which may be difficult to control.[20] Intraocular lenses (IOLs) are associated with a greater risk of visual axis opacities in this age group; aphakic optical correction without using an IOL is usually managed with either contact lenses or glasses. Implantation of an IOL in a second operation may be considered when the child is older.[19]

Technique

Two main types of surgical procedures are in common use throughout the world. In phacoemulsification (phaco), the natural lens is broken into small pieces and removed by suction, whereas in extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE), the lens is removed from its capsule and extracted from the eye, either whole or after being split into a small number of substantial pieces. In most surgeries, an IOL is inserted. Foldable lenses are generally used for the 2–3 mm (0.08–0.12 in) phaco incision, while non-foldable lenses can be placed through the larger extracapsular incision. The small incision size used in phacoemulsification generally allows for sutureless incision closure. ECCE uses a larger incision of 10–12 mm (0.39–0.47 in) and usually requires stitches; this requirement led to a variation of ECCE, known as manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS), which does not usually need stitches.[2]

Cataract surgery using intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE) has been superseded by phacoemulsification and MSICS over time, and is now rarely performed.[2] ECCE has largely become a contingency procedure to deal with complications during surgery.[21] Phacoemulsification is the most commonly performed cataract procedure in the developed world. The high capital and maintenance costs of a phacoemulsification machine and of the associated disposable equipment, however, has meant ECCE and MSICS remain the most commonly performed procedures in developing countries.[2] Cataract surgery is commonly done as an out-patient or day-care procedure, which is cheaper than hospitalisation and an overnight stay, and there is evidence that day surgery has similar medical outcomes.[22]

Types of surgery

The main types of surgical techniques used in cataract surgery are phacoemulsification and manual extraction.[9]

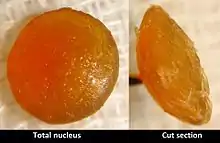

- Phacoemulsification involves the use of a machine with an ultrasonic handpiece equipped with a titanium or surgical steel tip, which vibrates at an ultrasonic frequency—commonly 40 kHz—to emulsify the lens tissue. A second instrument, which is sometimes called a "cracker" or "chopper", may be used from a side port to break the hard cataract nucleus into smaller pieces, making emulsification and the aspiration of cortical material (the soft part of the lens around the nucleus) easier. After phacoemulsification of the lens nucleus and cortical material is completed, a dual irrigation–aspiration (I-A) probe or a bimanual I-A system is used to remove the remaining peripheral cortical material.[7]

- Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery has been reported to be safe, and may have less adverse effects on the cornea and macula than manual phacoemulsification. The laser is used to make the corneal incision, execute the capsulotomy and initiate lens fragmentation, which reduces energy requirements for phacoemulsification. It offers high-precision, effective lens fragmentation at lower power levels and good optical quality: however, as of 2022, the technique has not been shown to have significant visual, refractive or safety benefits over manual phacoemulsification, and it has a higher cost.[2][23][24]

- Extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE), also known as manual extracapsular cataract extraction, is the removal of almost the entire natural lens in one piece, while the elastic lens capsule (posterior capsule) is left intact to allow implantation of an intraocular lens.[2] The lens is manually removed through a 10–12 mm (0.39–0.47 in) incision in the cornea or sclera. Although it requires a larger incision and the use of stitches, this method may be preferable for people with very hard cataracts, as well as other situations in which phacoemulsification is problematic.[21]

- Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) is an evolution of ECCE; the entire lens is removed from the eye through a self-sealing scleral tunnel wound. A well-constructed scleral tunnel is held closed by internal pressure, is watertight, and does not require suturing. The wound is relatively smaller than the one in ECCE, but is still markedly larger than a phaco wound. Comparative trials of MSICS against phaco in dense cataracts have found no significant difference in outcomes, although MSICS had shorter operating times and significantly lower costs.[6] MSICS has been prioritized as the method of choice in developing countries, because it provides high-quality outcomes with less surgically-induced astigmatism than ECCE, no suture-related problems, quick rehabilitation, and fewer post-operative visits. MSICS is generally easy and fast to learn for the surgeon, cost-effective and applicable to almost all types of cataract.[8]

- Intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE) is the removal of the lens and the surrounding lens capsule in one piece. The procedure has a relatively high rate of complications in comparison to other techniques, due to the large incision required and pressure placed on the vitreous body. It has therefore been largely superseded and is rarely performed in countries where operating microscopes and high-technology equipment are readily available.[2] After lens removal by ICCE, an intraocular lens implant can be placed in either the anterior chamber or sutured into the ciliary sulcus.[7] Cryoextraction is a technique used in ICCE; the cataract is extracted using a cryoprobe, the refrigerated tip of which adheres to the tissue of the lens at the contact point by freezing with a cryogenic substance such as liquid nitrogen, facilitating its removal.[25] Cryoextraction may still be used for the removal of subluxated lenses.[26]

- Refractive lens exchange is effectively the same procedure used to replace a lens with high refractive error when other methods are not effective. There are risks in addition to cataract procedural risks.[2] A related procedure is the implantation of phakic intraocular lenses in series with the natural lens to correct vision in cases of high refractive errors.[27]

Ophthalmic viscosurgical devices

Ophthalmic viscosurgical devices (OVDs) are a class of clear, gel-like materials used in cataract surgery to maintain the volume and shape of the anterior chamber of the eye, and protect intraocular tissues during the procedure. They were originally called viscoelastic substances (viscoelastics). Their consistency allows surgical instruments to move through them, although they do not flow and retain their shape in case of low shear stress. OVDs are available in several formulations, which may be combined or used individually as best suits the procedure. OVDs are introduced into the anterior chamber at the start of the procedure and removed at the end, when they are replaced by a buffered saline solution.[7] Cohesive OVDs tend to adhere to themselves, a characteristic that makes their removal easier.[28]

Intraocular lenses

.jpg.webp)

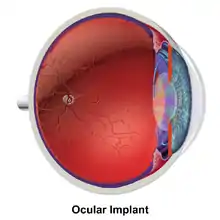

After the removal of a cataract, an intraocular lens (IOL) is usually implanted into the eye to provide refractive compensation for the lack of the damaged natural lens. A foldable IOL may be implanted through a 1.8 to 2.8 mm (0.071 to 0.110 in) incision, whereas a rigid poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) lens requires a larger cut. Foldable IOLs are made of silicone, hydrophobic, or hydrophilic acrylic material of appropriate refractive power; it is folded using a holder/folder or a proprietary insertion device, which is provided with the lens itself.[29] The IOL is inserted through the incision, usually into the capsular bag within the posterior chamber (in-the-bag implantation). Sometimes, a sulcus implantation—in front or on top of the capsular bag, but behind the iris—may be required because of posterior capsular tears or zonulodialysis. This requires a modification of refractive power because of the more-anterior placement on the optical axis.[30]

Other designs of multifocal intraocular lens that focus light from distant and near objects, working with similar effect to bifocal or trifocal eyeglasses, are also available. Pre-operative patient selection and good counselling is necessary to avoid unrealistic expectations and post-operative patient dissatisfaction, and possibly a requirement to replace the lens.[31] Acceptability of these lenses has improved, and studies have shown good results in patients selected for expected compatibility.[32]

One model of accommodating lens has two hinged struts on opposite edges, which displace the lens along the optical axis when an inward transverse force is applied to the haptic loops at the outer ends of the struts—the components transferring the movement of the contact points to the device—while recoiling when the same force is reduced. The lens is implanted in the eye's lens capsule, where the contractions of the ciliary body, which would focus the eye with the natural lens, are used to focus the implant, instead.[2][33]

IOLs used in correcting astigmatism have different curvature on two orthogonal axes, as on the surface of a torus: for this reason, they are called toric lenses. The STAAR Surgical Intraocular Lens was the first-such lens developed in the United States; it may correct up to 3.5 dioptres. Alcon created a different model of toric lens that may correct up to 3 dioptres of astigmatism. To achieve the most benefit from a toric lens, the surgeon must place the lens with the axes of curvature to suit any existing astigmatism. Intraoperative aberrometry[Note 1] can be used to assist the surgeon in toric lens placement and minimize astigmatic errors.[34][35]

Monofocal IOLs provide accurately focused vision at one distance only; far, intermediate, or near. People who are fitted with these lenses may need to wear glasses or contact lenses while reading or using a computer. These lenses usually have uniform spherical curvature.[36]

Cataract surgery may be performed to correct vision problems on both sides, too; if both eyes are suitable, people are usually advised to consider monovision. This procedure involves inserting an IOL providing near vision into one eye, while using one that provides distance vision for the other eye. Although most people can adjust to having monofocal IOLs with differing focal length, some cannot compensate and may experience blurred vision at both near and far distances. An IOL optimised for distance vision may be combined with an IOL that optimises intermediate vision, instead of near vision, as a variation of monovision.[29]

The first aspheric IOLs were developed in 2004; they have a flatter periphery than the middle of the lens, improving contrast sensitivity. The effectiveness of aspheric IOLs depends on a range of conditions and they may not always provide significant benefit.[37]

Some IOLs are able to absorb ultraviolet and high-energy blue light, thus mimicking the functions of the natural crystalline lens of the eye, which usually filters potentially harmful frequencies. A 2018 Cochrane review found there is unlikely to be a significant difference in distance vision between blue-filtering and plain lenses, and was unable to identify a difference in contrast sensitivity or colour discrimination.[38][39]

The light-adjustable IOL was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017.[40] This type of IOL is implanted in the eye and then treated with ultraviolet light to alter the curvature of the lens.[41]

In some cases, it may be necessary or desirable to insert an additional lens over the already implanted one, also in the posterior capsule. This type of IOL placement is called "piggyback" IOLs and is usually considered when the visual outcome of the first implant is not optimal.[42] In such cases, implanting another IOL over the existing one is considered safer than replacing the initial lens. This approach may also be used in people who need high degrees of vision correction.[43]

The appropriate refractive power of the IOL must be selected, much like a spectacle lens prescription, to provide the desired refractive outcome. Pre-operative measurements, including corneal curvature, axial length, and white-to-white measurements are used to estimate the required power of the IOL. These methods include several formulae, including Hagis,[44] Hoffer Q,[44] Holladay 1,[44] Holladay 2,[44] and SRK/T.[45] Free online calculators use similar input data.[44] A history of LASIK surgery requires different calculations to take this into account.[44] Refractive results using power calculation formulae based on pre-operative biometrics leave people within 0.5 dioptres of target (correlates to visual acuity of 6/7.5 (20/25) when targeted for distance) in 55% of cases and within one dioptre (correlates to 6/12 (20/40) when targeted for distance) in 85% of cases. Developments in intra-operative wavefront technology have demonstrated power calculations that provide improved outcomes, yielding 80% of patients within 0.5 dioptres (7/7.5 (20/25) or better).[35]

Cost is an important aspect of these lenses. Although Medicare covers the cost of monofocal IOLs in the United States, people will have to pay the price difference if they choose more expensive lenses.[46]

Pre-operative evaluation

An eye examination or pre-operative evaluation by an eye surgeon is necessary to confirm the presence of a cataract and to determine the patient's suitability for surgery.[2][47][48] The patient must fulfill certain requirements:

- The degree of reduction of vision due largely to the cataract should be evaluated. While the existence of other sight-threatening diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration or glaucoma, does not preclude cataract surgery, less improvement may be expected in their presence.[2]

- The eyes should have a normal pressure, or any glaucoma should be adequately controlled with medications. In cases of uncontrolled glaucoma, a combined cataract-glaucoma procedure (phaco-trabeculectomy) can be planned and performed.[48]

- The pupil should be adequately dilated using eyedrops; if pharmacologic pupil dilation is insufficient, procedures for mechanical pupil dilatation may be needed during the surgery.[49]

- People with retinal detachment may be scheduled for a combined vitreo-retinal procedure, along with PCIOL implantation.[47]

- People taking tamsulosin (Flomax), a common drug for enlarged prostate, are prone to developing a surgical complication known as intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS), which must be correctly managed to avoid posterior capsule rupture;[Note 2] prospective studies have shown the risk is greatly reduced if the surgeon is informed that the person is taking the drug before the operation, and has easy access to appropriate alternative techniques.[50]

- A Cochrane Review of three randomized clinical trials, including over 21,500 cataract surgeries, examined whether routine pre-operative medical testing resulted in a reduction of adverse events during surgery. Results showed performing pre-operative medical testing did not result in a reduction of risk of intra-operative or post-operative medical adverse events, compared to surgeries with no or limited pre-operative testing.[51]

Operation procedures

Antibiotics may be administered pre-operatively, intra-operatively, or post-operatively. Frequently, a topical corticosteroid or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is used in combination with topical antibiotics in the post-operative phase.[7]

Most cataract operations are performed under local anaesthetic, allowing the patient to return home the same day. The use of an eye patch may be indicated, usually for some hours and while sleeping, after which the patient is instructed to use anti-inflammatory eyedrops to control inflammation, and antibiotic eyedrops to prevent infection. Lens and cataract procedures are commonly performed in an out-patient setting; in the United States, 99.9% of lens and cataract procedures in 2012 were done in an out-patient setting.[7][52]

Occasionally, a peripheral iridectomy may be performed to minimize the risk of pupillary block glaucoma.[7] Surgical iridectomy can be performed manually or with a Nd:YAG laser. Laser peripheral iridotomy may be performed either before or following cataract surgery.[53]

The iridectomy hole is larger when done manually than when performed with a laser. Some negative side-effects have been registered following the execution of the manual surgical procedure, such as the opening of the iris being visible to others, and the passage of light into the eye through the new hole, creating visual disturbance. In the case of visual disturbance, the eye and brain often learn to compensate and ignore the effects over two months. Sometimes, the peripheral iris opening can heal and the hole ceases to exist.[53][54]

The most commonly used procedures are phacoemulsification and manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS). In either of these procedures, it can sometimes be necessary to convert to ECCS to deal with a problem better managed through a larger incision.[21]

Phacoemulsification

The surgical procedure in phacoemulsification for removal of cataract is typically performed under an operating microscope. Either topical, sub-tenon, peribulbar, or retrobulbar local anaesthesia is used, usually causing little or no discomfort.[55] Topical anaesthetics are the most commonly used category; they are placed on the globe of the eye as eyedrops (before surgery), or in the globe (during surgery).[56] Local-anaesthetic injection techniques include sub-conjunctival injections and injections behind the globe (retrobulbar block) to block regional nerves and prevent eye movement.[7] Intravenous sedation may be combined with the local anaesthetic. General anaesthesia and retrobulbar blocks were historically used for intracapsular cataract surgery, but local and topical anaesthesia are commonly used for small incision surgery and phacoemulsification.[2]

The operation site is prepared by disinfecting the area around the eye and the rest of the face, while the eyeball is exposed by using an eyelid speculum.[57]

Entry into the eye is made through a minimal incision;[7] the incision for cataract surgery has evolved along with the techniques for cataract removal and IOL placement. In phacoemulsification, the size depends on the requirements for IOL insertion. A more-posterior incision simplifies wound closure and decreases induced astigmatism, but it is more likely to damage blood vessels nearby. With foldable IOLs, it is sometimes possible to use incisions smaller than 3.5 mm (0.14 in). The shape, position, and size of the incision affect the capacity for self sealing, the tendency to induce astigmatism, and the surgeon's ability to maneuvre instruments through the opening.[7] One or two smaller side-port incisions at 60-to-90 degrees from the main incision may be needed to access the anterior chamber with additional instruments.[57]

Ophthalmic viscosurgical devices (OVDs) are injected into the anterior chamber to support, stabilize, and protect the eyeball to help maintain eye shape and volume, and to distend the lens capsule during IOL implantation.[28] In capsulorhexis, a circular opening is made on the front surface of the lens capsule to access the lens within. In phacoemulsification, an anterior continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis is used to create a round, smooth-edged opening through which the surgeon can emulsify the lens nucleus, and then implant the intraocular lens.[58]

The cataract's outer (cortical) layer is then separated from the capsule by a gentle, continuous flow or pulsed dose of liquid from a cannula, which is injected under the anterior capsular flap, along the edge of the capsulorhexis opening. This step is called hydrodissection.[59][60] In hydrodelineation, fluid is injected into the body of the lens through the cortex against the nucleus of the cataract, which separates the hardened nucleus from the softer cortex shell by flowing along the interface between them. As a result, the smaller hard nucleus can be more-easily phacoemulsified. The posterior cortex serves as a buffer, protecting the posterior capsule membrane. The smaller size of the separated nucleus requires shallower and less-peripheral grooving, and produces smaller fragments after cracking or chopping. The posterior cortex also maintains the shape of the capsule, which reduces the risk of posterior capsule rupture.[61]

After nuclear cracking or chopping (if needed), the cataract is destroyed using ultrasound and the remaining lens cortex (outer layer of lens) material from the capsular bag is carefully aspirated; moreover, in capsular polishing, the remaining epithelial cells from the capsule are removed if necessary.[62] The folded intraocular replacement lens is implanted, usually into the remaining posterior capsule, and correct unfolding is ensured. Aligning the IOL in the correct axis to counteract astigmatism is necessary for a toric IOL.[2]

OVDs that were injected to stabilize the anterior chamber, protecting the cornea from damage and distending the cataract's capsule during IOL implantation, are removed from the eye to prevent post-operative viscoelastic glaucoma, a severe intra-ocular pressure increase. This is done via suction from the irrigation-aspiration instrument and replacement by buffered saline solution (BSS). Removal of OVDs from behind the implant reduces the risk and magnitude of post-operative pressure spikes or capsular distention.[7]

In the final step, the wound is sealed by elevating the pressure inside the globe with BSS, which presses the internal tissue against the external tissue of the incision, holding it closed. If this does not achieve a satisfactory seal, a suture may be added. The wound is then hydrated.[7]

Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS)

Many of the steps followed during MSICS are similar, if not identical, as for phacoemulsification; the main differences are related to the alternative method of incision and cataract extraction from the capsule and eye. Preparation may begin three-to-seven days before surgery, with the pre-operative application of NSAIDs and antibiotic eyedrops.[8] If the IOL needs to be placed behind the iris, the pupil is dilated by using drops to help better visualise the cataract. Pupil-constricting drops are reserved for secondary implantation of the IOL in front of the iris, when the cataract has already been removed without primary IOL implantation. Anaesthesia may be placed topically as eyedrops, or injected either next to (peribulbar) or behind (retrobulbar) the eye,[56] or through sub-tenons. Local anaesthetic nerve blocking has been recommended to facilitate surgery.[8] Topical anaesthetics may be used at the same time as an intracameral lidocaine injection to reduce pain during the operation.[56] Oral or intravenous sedation may also be used to reduce anxiety. General anaesthesia is rarely necessary, but may be used for children and adults whose medical or psychiatric issues significantly affect their ability to remain still during the procedure.[7][56]

The operation may occur on a stretcher or a reclining examination chair. The eyelids and surrounding skin are swabbed with a disinfectant, such as 10% povidone-iodine, and topical povidone-iodine is applied to the eye. The face is covered with a cloth or sheet with an opening for the operative eye. The eyelid is held open with a speculum to minimize blinking during surgery.[57] Pain is usually minimal in properly anaesthetised eyes, though a pressure sensation and discomfort from the bright operating microscope light is common.[7] Bridle sutures[Note 3] may be used to help stabilize the eyeball during sclerocorneal tunnel incision, and during extraction of the nucleus and epinucleus through the tunnel.[8]

The small incision into the anterior chamber of the eye is made at or near the corneal limbus, where the cornea and sclera meet, either superior or temporal.[8] Advantages of the smaller incision include use of few-to-no stitches and shortened recovery time.[2] The MSICS incision is small in comparison with the earlier ECCE incision, but considerably larger than the one executed in phacoemulsification. The precise geometry of the incision is important, as it affects the self-sealing of the wound and can cause astigmatism by distortion of the cornea during healing. A sclerocorneal or scleral tunnel incision is commonly used, since it reduces the risk of induced astigmatism if suitably formed.[6][57] A sclerocorneal tunnel, a three-phase incision, starts with a shallow incision perpendicular to the sclera, followed by an incision through the sclera and cornea approximately parallel to the outer surface, and then a beveled incision into the anterior chamber. This structure provides the self-sealing characteristic, because internal pressure presses together the faces of the incision.[8]

The depth of the anterior chamber and position of the posterior capsule may be maintained during surgery by OVDs or an anterior chamber maintainer, which is an auxiliary cannula providing a sufficient flow of BSS to maintain the stability of the shape of the chamber and internal pressure.[63][64] Capsulotomy, also known as a cystotomy, is then performed through an instrument called cystotome, in order to open the surface of the lens capsule.[65] The continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis technique is frequently used. An anterior capsulotomy consists in the opening of the front portion of the lens capsule, providing enough access to the cataract that needs to get removed;[66] on the other hand, a posterior capsulotomy involves the opening of the back portion of the lens capsule, which is not usually necessary or desirable, unless it has opacified.[67] The types of capsular openings commonly used in MSICS are continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, can-opener capsulotomy and envelope capsulotomy.[63]

The cataract lens is then removed from the capsule and anterior chamber using hydroexpression,[Note 4] viscoexpression,[Note 5] or more direct mechanical methods.[63][68][69] Following cataract removal, an IOL is usually inserted into the posterior capsule.[7] When the posterior capsule is damaged, the IOL may be inserted into the ciliary sulcus,[30] or a glued intraocular lens technique may be applied.[70] After the IOL is inserted, the ophthalmic viscosurgery device is aspirated and replaced with BSS, and the wound is closed. The surgeon must check whether the incision does not leak fluid, because wound leakage increases the risk of penetration into the eye by microorganisms, thus predisposing it to endophthalmitis. An antibiotic/steroid combination eyedrop is put in, and an eye-shield may be applied, sometimes supplemented with an eyepatch.[7]

Converting to ECCE to manage a contingency

Sometimes a shift from a phacoemulsification procedure to ECCE may be necessary.[21] This may occur in the event of posterior capsule rupture, zonular dehiscence,[Note 6] or a dropped nucleus[Note 7] with a nuclear fragment more than half the size of the cataract;[21] problematic capsulorhexis with a hard cataract;[21] or a very dense cataract where phacoemulsification is likely to cause permanent damage to the cornea.[21] Similarly, a change from MSICS to ECCE is appropriate whenever the nucleus is too large for the MSICS incision,[21] as well as in cases where the nucleus is found to be deformed during MSICS on a nanophthalmic eye.[Note 8][21]

Complications

During surgery

Posterior capsular rupture, a tear in the posterior capsule of the natural lens, is the most common complication during cataract surgery, with its rate approximately ranging from 0.5% to 5.2%.[2] Surgical management may involve anterior vitrectomy and occasionally, alternative planning for implanting the IOL, either in the ciliary sulcus—the space between the iris and the ciliary body—in the anterior chamber in front of the iris, or less commonly, sutured to the sclera. Posterior capsule rupture can cause lens fragments to be retained, corneal oedema, and cystoid macular oedema; it is also associated with a six-times increase in the risk of endophthalmitis and as much as a nineteen-times increase in the risk of retinal detachment.[2][71] Management methods include the Intraocular lens scaffold procedure.[72]

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage is a rare complication of intraocular surgery, which occurs when damaged ciliary arteries bleed into the space between the choroid and the sclera.[73] It is a potentially vision-threatening pathology. Risk factors for suprachoroidal hemorrhage include anterior chamber intraocular lens (ACIOL), axial myopia, advanced age, atherosclerosis, glaucoma, systolic hypertension, tachycardia, uveitis and previous ocular surgery. Suprachoroidal hemorrhage must be treated immediately and effectively in order to preserve visual functions.[7]

Intraoperative floppy iris syndrome has an incidence ranging from around 0.5% to 2.0%.[2] Iris or ciliary body injury has an incidence of about 0.6%-1.2%.[2] In the event of a posterior capsule rupture, fragments of the nucleus can find their way through the tear into the vitreous chamber; this is called posterior dislocation of nuclear fragments. Recovery of the fragments is not always desirable and it is rarely successful. The rest of the fragments should generally be stabilised first, and vitreous needs to be prevented from entering the anterior chamber. Removal of the fragments may be best referred to a vitreoretinal specialist.[7]

Other complications include failure to aspirate all lens fragments, leaving some in the anterior chamber,[71] and incisional burns, caused by overheating of the phacoemulsification tip when ultrasonic power continues while the irrigation or aspiration lines are blocked—the flow through these lines is used to keep the tip cool. Burns to the incision may make closure difficult and can cause corneal astigmatism.[7]

After surgery

Complications after cataract surgery are relatively uncommon. Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) does not directly threaten vision, but its cases are monitored with increasing interest, since the interaction between the vitreous body and the retina might play a decisive role in the development of major pathological vitreoretinal conditions. PVD may be more problematic with younger patients because many people older than 60 have already gone through PVD. PVD may be accompanied by peripheral light flashes and increasing numbers of floaters.[74]

Some people develop posterior capsular opacification (PCO), also called an "after-cataract". After cataract surgery, posterior capsular cells usually undergo hyperplasia and cellular migration as part of a physiological change, showing up as a thickening, opacification and clouding of the posterior lens capsule, which is left behind after the cataract is removed, for placement of the IOL. This may compromise visual acuity, and can be safely and painlessly corrected by using a Nd:YAG laser to clear the central portion of the opacified posterior pole of the capsule (posterior capsulotomy).[75] This creates a clear central visual axis, which improves visual acuity.[76] In very thick opacified posterior capsules, a manual surgical capsulectomy might be needed. A posterior capsulotomy must be taken in consideration in the event of IOL replacement, because vitreous can migrate toward the anterior chamber through the opening previously occluded by the IOL. Posterior capsule opacification has an incidence of about 0.3% to 28.4%.[2]

Retinal detachment normally occurs at a prevalence of 1 in 1,000 (0.1%); however, people who have had cataract surgery are at an increased risk (0.5–0.6%) of developing rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD)—the most common form of the condition.[77] Cataract surgery increases the rate of vitreous humour liquefaction, which leads to increased rates of RRD.[78] When a retinal tear occurs, vitreous liquid enters the space between the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and presents as flashes of light (photopsia), dark floaters, and loss of peripheral vision.[77] Toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS), a non-infectious inflammatory condition, may also occur following cataract surgery: it is usually treated with topical corticosteroids in high dosage and frequency.[79]

Endophthalmitis is a serious infection of intraocular tissues, usually following intraocular surgery complications or penetrating trauma, and one of the most severe. It rarely occurs as a complication of cataract surgery, due to the use of prophylactic antibiotics: still, there is some concern that the clear cornea incision might predispose to the increase of endophthalmitis, although no conclusive study has corroborated this suspicion.[80] An intracameral injection of antibiotics may be used as a preventive measure. A meta-analysis showed the incidence of endophthalmitis after phacoemulsification to be 0.092%. The risk gets higher in association to factors such as diabetes, advanced age, larger incision procedures,[29] and vitreous' communication with the anterior chamber (due to posterior capsule rupture). The risk of vitreous infection is at least six times higher than for the aqueous.[81] Endophthalmitis' typical presentation occurs within two weeks after the procedure, with manifestations such as decreased visual acuity, red-eye and pain. Hypopyon occurs about 80% of the time. Common infective agents include coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus in about 80% of infections. Management includes vitreous humour tap and injection of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Outcomes can be severe even with treatment, and may range from permanently decreased visual acuity to the complete loss of light perception, depending on the microbiological etiology.[2]

Glaucoma may occur and may be very difficult to control. It is usually associated with inflammation, especially when small fragments or chunks of the nucleus enter the vitreous cavity. Some experts recommend early intervention by posterior pars plana vitrectomy when this condition occurs. In most cases, raised post-operative intraocular pressure is transient and benign, usually returning to baseline within 24 hours without intervention. Glaucoma patients may experience further visual field loss or a loss of fixation, and are more likely to experience intraocular pressure spikes.[82] On the other hand, secondary glaucoma is an important complication of surgery for congenital cataracts: patients can develop this condition even several years after undergoing cataract surgery, so they need lifelong surveillance.[83]

Mechanical pupillary block manifests when the anterior chamber gets shallower as a result of the obstruction of the aqueous humour flow through the pupil by the vitreous face or IOL.[84] This is caused by contact between the edge of the pupil and an adjacent structure, which blocks the flow of aqueous through the pupil itself. The iris then bulges forward and closes the angle between the iris and cornea, blocking drainage through the trabecular meshwork and causing an increase in intraocular pressure. Mechanical pupillary block has mainly been identified as a complication of anterior chamber intraocular lens implantation, but has been known to occur occasionally after posterior IOL implantation, as well.[85]

Swelling of the macula, the central part of the retina, results in macular oedema and can occur a few days or weeks after surgery. Most such cases can be successfully treated. Preventative use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been reported to reduce the risk of macular oedema to some extent.[86] Uveitis–glaucoma–hyphema syndrome is a complication caused by the mechanical irritation of a mis-positioned IOL over the iris, ciliary body or iridocorneal angle.[87]

Other possible complications include elevated intraocular pressure;[84] swelling or oedema of the cornea, which is sometimes associated with transient or permanent cloudy vision (pseudophakic bullous keratopathy); displacement or dislocation of the IOL implant; unplanned high refractive error—either myopic or hypermetropic—due to errors in the ultrasonic biometry (measurement of the eye length and calculation of the required intraocular lens power); cyanopsia, which often occurs for a few days, weeks or months after removal of a cataract; and floaters, which commonly appear after surgery.[39]

It may be necessary to exchange,[Note 9] remove[Note 10] or reposition[Note 11] an IOL after surgery, for any of the following reasons:[84]

- Capsular block syndrome, which consists in the hyper-distention of the lens capsular bag, due to the IOL blocking fluid from draining through the anterior capsulotomy. This may cause a myopic refractive error;[84]

- Chronic anterior uveitis, which is a persistent inflammation of the anterior segment;[84]

- Chronic loss of endothelial cells faster than the rate due to normal aging;[84]

- Iris pigment epithelium loss;[84]

- Physical pain;[84]

- Progressive elongation of the pupil in direction of the IOL's long axis;[84]

- Progressive closing of the anterior chamber angle, due to propagation of anterior synechiae without apparent anterior uveitis;[84]

- Incorrect IOL refractive power;[84]

- Incorrect positioning of the IOL (including decentring, tilt, or rotation), which partially prevents its correct function;[84]

- Damage or deformation of the IOL;[84]

- Unexpected optical results due to defects of the IOL;[84]

- Undesirable optical phenomena reported by the patient due to any other cause.[84]

Risk

Statistically, cataract surgery and IOL implantation have the safest and highest success rates of any eye care-related procedures.[7] As with any type of surgery, however, some level of risk remains. As of 2011, cataract surgery is the most frequently performed surgical procedure in the United States, with 1.8 million Medicare beneficiaries undergoing the procedure in 2004. This rate is expected to increase as the population ages.[88]

Most complications of cataract surgery do not result in long-term visual impairment, but some severe complications can lead to irreversible blindness.[88] A survey of adverse results affecting Medicare patients recorded between 2004 and 2006 showed an average rate of 0.5% for one or more severe post-operative complications, with the rate decreasing by about 20% over the study period. The most important risk factors identified were diabetic retinopathy and a combination of cataract surgery with another intraocular procedure on the same day. In the study, 97% of the surgeries were not combined with other intraocular procedures; the remaining 3% were combined with retinal, corneal or glaucoma surgery on the same day.[88]

Recovery and rehabilitation

Following cataract surgery, side-effects such as grittiness, watering, blurred vision, double vision, and a red or bloodshot eye may occur, although they usually clear after a few days. Full recovery from the operation can take four-to-six weeks.[89] Patients are usually advised to avoid getting water in the eye during the first week after surgery, and to avoid swimming for two-to-three weeks as a conservative approach, to minimise risk of bacterial infection.[7] Most people can return to normal activities the day after phacoemulsification surgery.[90] Depending on the procedure, they should avoid driving for at least 24 hours after the surgery, largely due to effects from the anaesthesia, possible swelling affecting focus, and pupil dilation causing excessive glare. At the first post-operative check, the surgeon will usually assess whether the patient's vision makes them suitable for driving.[90]

With small-incision self-sealing wounds used with phacoemulsification, some of the post-operative restrictions common with intracapsular and extracapsular procedures are not relevant. Restrictions against lifting and bending were intended to reduce the risk of the wound opening, because straining increases intraocular pressure. With a self-sealing tunnel incision, however, higher pressure closes the wound more tightly. Routine use of a shield is not usually required, because inadvertent finger pressure on the eye should not open a correctly structured incision, which should only open to point pressure.[7] After surgery, patients need to prevent contamination by avoiding rubbing their eyes, as well as the use of eye makeup, face cream or lotions. Any kind of contact with excessive dust, wind, pollen or dirt should also be avoided. Moreover, people are advised to wear sunglasses on bright days, since the eyes become more sensitive to bright light for a prolonged period of time in the aftermath of surgery.[91]

Topical anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics are commonly used in the form of eyedrops to reduce the risk of inflammation and infection. A shield or eye-patch may be prescribed to protect the eye while sleeping. The eye will be checked to ensure the IOL remains in place, and once it has fully stabilized (after about six weeks), vision tests will be used to check whether prescription lenses are needed.[2][89] In cases where the focal length of the IOL is optimised for distance vision, reading glasses are generally needed for near focus.[92]

In some cases, people are dissatisfied with the optical correction provided by the initial implants, making removal and replacement necessary; this can occur with more complex IOL designs, as the patient's expectations might not match with the compromises inherent in these designs, or they might not be able to accommodate the difference in distance and near-focusing of monovision lenses.[31] The patient should not participate in contact or extreme sports, or similar activities, until cleared to do so by the eye surgeon.[93]

Outcomes

After full recovery, visual acuity depends on the underlying condition of the eye, the choice of IOL, and any long-term complications associated with the surgery. More than 90% of operations are successful in restoring useful vision, with a low complication rate.[94] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least 80% of eyes should have a presenting visual acuity of 6/6 to 6/18 (20/20 to 20/60) after surgery, which is considered a good enough visual outcome; the percentage is expected to reach at least 90% with best correction. Acuity of between 6/18 and 6/60 (20/60 to 20/200) is regarded as borderline, whereas a value worse than 6/60 (20/200) is considered poor. Borderline or poor visual outcomes are usually influenced by pre-surgery conditions such as glaucoma, macular disease, and diabetic retinopathy.[95]

A ten-year prospective survey on refractive outcomes from a UK National Health Service (NHS) cataract surgery service from 2006 to 2016 showed a mean difference between the targeted and outcome refraction of −0.07 dioptres, with a standard deviation of 0.67, and a mean absolute error of 0.50 dioptres. 88.76% were within one diopter of target refraction and 62.36% within 0.50 dioptres.[96]

According to a 2009 study conducted in Sweden, factors that affected predicted refraction error included sex, pre-operative visual acuity and glaucoma, together with other eye conditions; on the opposite, second-eye surgery, macular degeneration, age and diabetes did not affect the predicted outcome. Prediction error decreased with time, which is likely due to the use of improved equipment and techniques, including more-accurate biometry.[97] A 2013 American survey involving nearly two million bilateral cataract surgery patients found immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery was statistically associated with worse visual outcomes than for delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery; however, the difference was small and might not be clinically relevant.[98]

There is a tendency for post-operative refraction to vary slightly over several years. A small overall myopic shift has been recorded in 33.6% and a small hypermetropic shift in 45.2% of eyes with the remaining 21.2% in the study having no reported change. Most of the change occurred during the first year after surgery.[99]

Phacoemulsification via a coaxial incision[Note 12] may be associated with less astigmatism than average for bimanual incisions,[Note 13] but the difference was found to be small and the evidence statistically uncertain.[100][101]

History

Cataract surgery has a long history in Europe, Asia, and Africa. It is one of the most common and successful procedures in worldwide use, thanks to improvements in techniques for cataract removal and developments in intraocular lens (IOL) replacement technology, in implantation techniques, and in IOL design, construction, and selection.[102] Surgical techniques that have contributed to this success include microsurgery, viscoelastics, and phacoemulsification.[103]

Couching

Couching is the earliest-documented form of cataract surgery, and one of the oldest surgical procedures ever performed. In this technique, the lens is dislodged and pushed aside, but not removed from the eye, thus removing the opacity, but also the ability to focus. After being used regularly for centuries, couching has been mostly abandoned in favor of more effective techniques over time, due to its generally poor outcomes, but is currently routinely practiced only in remote areas of developing countries.[104][105]

Cataract surgery was first mentioned in the Babylonian code of Hammurabi 1750 BCE.[106] The earliest known depiction of cataract surgery is on a statue from the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt (2467–2457 BCE).[106] According to Francisco J Ascaso et al, a "relief painting from tomb number TT 217 in a worker settlement in Deir el-Medina" shows "the man buried in the tomb, Ipuy ... one of the builders of royal tombs in the renowned Valley of the Kings, circa 1279–1213 BC" as he underwent cataract surgery. Although direct evidence for cataract surgery in ancient Egypt is lacking, the indirect evidence, including surgical instruments that could have been used for the procedure, show that it was possible. It is assumed that the couching technique was used.[106][107]

Couching was practiced in ancient India and subsequently introduced to other countries by Indian physician Sushruta (c. 6th century BCE),[108] who described it in his medical text, Sushruta Samhita ("Compendium of Sushruta"); the work's Uttaratantra section[lower-alpha 1] describes an operation in which a curved needle was used to push the opaque "phlegmatic matter"[lower-alpha 2] in the eye out of the way of vision. The phlegm was then said to be blown out of the nose. The eye would later be soaked with warm, clarified butter before being bandaged.[109] The removal of cataracts by surgery was introduced into China from India, and flourished in the Sui (581–618 CE) and Tang dynasties (618–907 CE).[110]

The first references to cataract and its treatment in Europe are found in 29 CE in De Medicina, a medical treatise by Latin encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus, which describes a couching operation.[111] In 2nd century CE, Galen of Pergamon, a prominent Greek physician, surgeon, and philosopher, reportedly performed an operation to remove a cataract-affected lens using a needle-shaped instrument.[112][113] Although many 20th-century historians have claimed that Galen believed the lens to be in the exact centre of the eye, there is evidence he understood the crystalline lens is located in the anterior aspect of the eye.[114]

The removal of cataracts by couching was a common surgical procedure in Djenné[115] and many other parts of Africa.[116] Couching continued to be used throughout the Middle Ages, and is still used to this day in some parts of Africa and in Yemen.[117][105] However, it has been proven to be an ineffective and dangerous method of cataract therapy, which often leads patients to blindness or only partially restored vision.[117] The technique has mostly been replaced by extracapsular cataract surgery, including phacoemulsification.[118]

The lens can also be removed by suction through a hollow instrument: bronze oral-suction instruments that seem to have been used for this method of cataract extraction during the 2nd century CE have been unearthed.[119] Such a procedure was described by the 10th-century Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi, who attributed it to Antyllus, a 2nd-century Greek physician. According to al-Razi, the procedure "required a large incision in the eye, a hollow needle, and an assistant with an extraordinary lung capacity".[120] This suction procedure was also described by Iraqi ophthalmologist Ammar Al-Mawsili in his 10th-century medical text, Choice of Eye Diseases.[120] He presented case histories of its usage, while claiming to have successfully performed it on a number of patients.[120]: p318 Extracting the lens has the benefit of removing the possibility of the lens migrating back into the field of vision.[121] According to oculist Al-Shādhili, a later variant of the cataract needle in 14th-century Egypt used a screw to grip the lens. It is not clear how often, if ever, this method was used; other writers, including Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi and Al-Shadhili, appear to have been unfamiliar with this procedure, or claimed it was ineffective.[120]: p319

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

In 1747, Jacques Daviel became the first modern European physician to successfully extract cataracts, having managed to remove the cataract from the eye capsule through a corneal incision with an estimated 50% success rate.[102] In 1753, Samuel Sharp performed the first-recorded surgical removal of the entire lens and lens capsule: the lens was removed from the eye through a limbal incision.[102] In America, cataract couching may have been performed in 1611,[122] while cataract extraction was most likely performed by 1776.[123] Cataract extraction by aspiration of lens material through a tube using suction was performed by Philadelphia-based surgeon Philip Syng Physick in 1815.[124]

King Serfoji II, Bhonsle of Thanjavur, India, reportedly performed cataract surgeries in the early 1800s, according to manuscripts stored in the Saraswathi Mahal Library.[125]

In 1884, Karl Koller became the first surgeon to apply a cocaine solution to the cornea as a local anaesthetic; the news of his discovery spread rapidly, but was not without controversy.[126][127]

Early-to-mid 20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, the standard surgical procedure was intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE). The work of Henry Smith, who first developed a safe, fast way to remove the lens within its capsule by external manipulation, was considered particularly influential; the capsule forceps, the discovery of enzymatic zonulysis by Joaquin Barraquer in 1957, and the introduction of cryoextraction of the lens by Tadeusz Krawicz and Charles Kelman in 1961 continued the development of ICCE.[7] Intracapsular cryoextraction was the favoured form of cataract extraction from the late 1960s to the early 1980s: it consisted in using a liquid-nitrogen-cooled probe tip, in order to freeze the encapsulated lens to the probe.[25][128]

In 1949, Harold Ridley introduced the concept of implantation of the intraocular lens (IOL) which allowed to make visual rehabilitation after cataract surgery a more efficient and comfortable process.[102]

Artificial IOLs, which are used to replace the eye's natural lens removed during cataract surgery, increased in popularity since the 1960s, and were first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1981. The development of IOLs was considered a notable innovation, as patients previously had to wear very thick glasses, or a special type of contact lens, in order to cope with the removal of their natural lens. IOLs can be used to correct other vision problems, such as toric lenses for correcting astigmatism.[36] IOLs can be classified as monofocal, toric, and multifocal lenses.[2]

Also in the 1960s, the development of A-scan ultrasound biometry contributed to provide more accurate predictions of implant refractive strength.[129]

In 1967, Charles Kelman introduced phacoemulsification, which uses ultrasonic energy to emulsify the nucleus of the crystalline lens and remove cataracts by aspiration without a large incision. This method of surgery reduced the need for an extended hospital stay and made out-patient surgery the standard. Patients who undergo cataract surgery rarely complain of pain or discomfort during the procedure, although those who have topical anaesthesia, rather than peribulbar block anaesthesia, may experience some discomfort.[130]

Late 20th century

Ophthalmic viscosurgical devices (OVDs) were introduced in 1972, and ended up facilitating the procedure and improving overall safety. An OVD is a viscoelastic solution, a gel-like substance used to maintain the shape of the eye at reduced pressure, as well as protect the inside structure and tissues of the eye without interfering with the operation.[102]

In 1980, D.M. Colvard made the cataract incision in the sclera, which limited induced astigmatism.[63] In the early 1980s, Danièle Aron-Rosa and colleagues introduced the neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser (Nd:YAG laser) for posterior capsulotomy.[7] In 1985, Thomas Mazzocco developed and implanted the first foldable IOL. Graham Barrett and associates pioneered the use of silicone, acrylics, and hydrogel lenses.[7]

According to Cionni et al (2006), Kimiya Shimizu began removing cataracts using topical anaesthesia in the late 1980s,[7] though Davis (2016) attributes the introduction of topical anaesthetics to R.A. Fischman in 1993.[102] In 1987, Blumenthal and Moissiev described the use of a reduced incision size for ECCE. They used a 6.5 to 7 mm (0.26 to 0.28 in) straight scleral tunnel incision 2 mm (0.079 in) behind the limbus with two side ports.[63]

In 1989, M. McFarland introduced a self-sealing incision architecture; in 1990, S.L.Pallin described a chevron-shaped incision that minimized the risk of induced astigmatism; in 1991, J.A. Singer described the frown incision, in which the ends curve away from the limbus, similarly reducing astigmatism.[63] Toric IOLs were introduced in 1992 and are used worldwide to correct corneal astigmatism during cataract surgery;[36][102] they have been approved by the FDA since 1998.[34] Also in the late 1990s, optical biometry based on partial coherence infrared interferometry was introduced: this technique improves visual resolution, offers much greater precision, and is much quicker and more comfortable than ultrasound.[129]

21st century

According to surveys of members of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, approximately 2.85 million cataract procedures were performed in the United States throughout 2004, while 2.79 million operations were executed in 2005.[131] In 2009, Praputsorn Kosakarn described a method for manual fragmentation of the lens, called "double-nylon loop", which consists in splitting the lens into three pieces for extraction, allowing a smaller, sutureless incision of 4.0 to 5.0 mm (0.16 to 0.20 in), and implantation of a foldable IOL. This technique used less expensive instruments and is suitable for use in developing countries.[63]

As of 2013, medical staffs had access to instruments that use infrared swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT), a non-invasive, high-speed method that can penetrate dense cataracts and collects thousands of scans per second, with the ultimate goal of generating high-resolution data in 2D or 3D.[129] As of 2021, approximately four million cataract procedures take place annually in the U.S. and nearly 28 million worldwide, a large proportion of which are performed in India; that is about 75,000 procedures per day globally.[132]

Regional practice and statistics

United Kingdom

In the UK, the practice of NHS healthcare providers referring people with cataracts to surgery widely varied as of 2017; many of the providers were only referring patients with moderate or severe vision loss, often with delays.[133] This practise occurred despite guidance issued by the NHS Executive in 2000, which urged providers to standardize care, streamline the process and increase the number of cataract surgeries performed, in order to meet the needs of the aging population.[134] In 2019, the national ophthalmology outcomes audit found five NHS trusts had complication rates of between 1.5% and 2.1%: however, since the first national cataract audit (held in 2010), there had been a 38% reduction in posterior capsule rupture complications.[135]

Asia

South Asia has the highest global age-standardized prevalence of moderate-to-severe visual impairment (17.5%) and mild visual impairment (12.2%). The estimated distribution of ophthalmologists ranges from more than 114 per million of population in Japan, to none in Micronesia. Cataract has traditionally been a major cause of blindness in less-developed countries in the region, and in spite of improvements to the volume and quality of cataract surgeries, the success rate (CSR) remains low for some of these nations.[136]

China

Cataracts are common in China; as of 2022, their estimated overall prevalence in Chinese people over 50 years old was 27.45%. The environment was an influential factor, with the prevalence being 28.79% in rural areas, and 26.66% in urban areas. Prevalence of cataract considerably varies by age group, as well: for ages 50-59, it is 7.88%; for ages 60-69, it is 24.94%; for ages 70-79, it is 51.74%; in people over 80 years old, it is 78.43%. The overall cataract-surgery coverage rate was 9.19%. The prevalence of cataract and cataract surgical coverage also significantly varies by region.[137]

India

India's cataract-surgical rate rose from just over 700 operations per million people per year in 1981, to 6,000 per million per year in 2011, thus getting increasingly closer to the estimated requirement of 8,000-8,700 operations per million per year needed to eliminate cataract blindness in the country. The rate's rise was partly linked to factors such as increased efficiency due to improved surgical techniques, application of day-case surgery, improvements in operating theatre design, and efficient teamwork with sufficient staff.[138]

In India, the pool of patients applying for cataract surgery has been widened through social marketing methods aimed to raise awareness about the condition and access to effective surgical treatments. The non-governmental organization (NGO) sector and Indian ophthalmologists have developed methods to deal with several problems affecting local communities, including outreach camps to find those needing surgery, counsellors to explain the system, locally manufactured equipment and consumables, and a tiered pricing structure using subsidies where appropriate.[138]

There have been occasional incidents in which several patients have been infected and developed endophthalmitis on the same day at some hospitals associated with eye camps in India. Journalists have reported blame being placed on the surgeons, the hospital administration, and other persons, but have not reported on those responsible for sterilizing the surgical instruments and operating theatres involved, whether all infections involved the same micro-organisms, the same theatres, or the same staff. One investigation found bacteria known to be associated with endophthalmia in the theatre and in the eyes of affected patients, and it was claimed the hospital had not followed the required protocol for infection control, but the investigation was ongoing and no findings were reported. Several instances of surgeons performing more operations per day than officially allowed have been reported, but the effects upon sterility of equipment or plausible infection pathways have not been explained.[139]

In 2022, digital news portal Scroll.in contacted the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, requesting official data on the number of patients who had contracted infections following surgery; according to their researches, since 2006, 469 people had either been blinded in one eye or had their vision seriously affected after undergoing surgery at eye camps. Further inquiries found the patients involved were at least 519, but the total number of surgeries for that period was not mentioned.[139] As of 2017, India is claimed to be performing about 6.5 million cataract surgeries per year, more than the US, Europe and China together.[140]

Africa

Cataracts are the main cause of blindness in Africa, and affect approximately half of the estimated seven million blind people on the continent, a number that is expected to increase with population growth by about 600,000 people per year. As of 2005, the estimated cataract-surgery rate was about 500 operations per million people per year. Progress on gathering information on epidemiology, distribution and impact of cataracts within the African continent has been made, but significant problems and barriers limiting further access to reliable data remain.[141]

These barriers relate to awareness, acceptance, and cost; some studies also reported community and family dynamics as discouraging factors. Most of the studies held locally reported that cataract-surgical rate was lower in females. The higher cataract-surgery coverage found in some settings in South Africa, Libya, and Kenya suggest many barriers to surgery can be overcome.[142]

According to the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, some sub-Saharan African countries have about one ophthalmologist per million people, while the National Center for Biotechnology Information stated the percentage of adults above the age of 50 in western sub-Saharan Africa who have developed cataract-induced blindness is about 6%—the highest rate in the world.[143]

A mathematical model using survey data from sub-Saharan Africa showed the incidence of cataracts varies significantly across the continent, with the required rate of surgery to maintain a visual acuity level of 6/18 (20/60) ranging from about 1,200 to about 4,500 surgeries per year per million people, depending on the area. Such variations may relate to genetic or cultural differences, as well as life expectancy.[144]

Nigeria

In 2011, 0.78% of the population of Nigeria were blind; more than 43% of these developed the condition from cataracts, whereas another 9% did it as a result of aphakia and complications from couching performed by itinerant practitioners. Although there are about 2.8 ophthalmologists per million population in Nigeria, the cataract-surgery rate is only 300 operations per million per year (compared with the WHO recommendation of 3,000 per million per year). Reasons cited for this situation include inadequate blindness prevention programs, shortage of funding and lack of government-led investments in training and services. Teaching hospitals do not have enough patient-surgical load to support training.[105]

South Africa

In South Africa, facilities vary from government hospitals, where subsidised operations for the disadvantaged may be charged at rates that cover the consumables, to private clinics in which up-to-date equipment is used and patients are charged at premium rates. Waiting times in government hospitals may be up to two years, whereas they are much shorter at private clinics. Some hospitals use a system in which two patients are operated upon for cataracts in the theatre at the same time, increasing the efficiency of facilities.[145] Some charitable organisations in the country provide pro bono cataract surgery in rural areas by using mobile clinics.[146][147]

As of 2023, the cataract-surgery rate in South Africa is less than half of the estimated requirement of at least 2,000 per million population per year needed to eliminate cataract blindness.[148][149] In 2011, Lecuona and Cook identified an inadequate level of human resources in the public sector to provide care for the indigent population.[149] The main barrier to increasing South Africa's rate of cataract surgery is inadequate surgery capacity: a higher annual rate of cataract surgeries by individual surgeons would improve cost effectiveness and personal skills, and also contribute towards an overall reduction of risk.[149]

Latin America

.jpg.webp)

A four-year longitudinal study of 19 Latin American countries published in 2010 showed most of the countries had increased their surgery rates over that period, with increases of up to 186%, but still failed to provide adequate surgical coverage. The study also shown a significant correlation between gross national income per capita and cataract-surgery rate in the countries involved.[150]

In a study published in 2014, the weighted-mean regional surgery rate was found to have increased by 70% from 2005 to 2012, rising from 1,562 to 2,672 cataract surgeries per million inhabitants. The weighted mean number of ophthalmologists per million inhabitants in the region was approximately 62. Cataract-surgery coverage widely varied across Latin America, ranging from 15% in El Salvador, to 77% in Uruguay. Barriers cited included cost of surgery and lack of awareness about available surgical treatment. The number of available ophthalmologists appeared to be adequate, but the number of those who practised eye surgery was unknown.[151]

A 2009 study showed that the prevalence of cataract blindness in people 50 years and older ranged from 0.5% in Buenos Aires, to 2.3% in parts of Guatemala. Poor vision due to cataracts ranged from 0.9% in Buenos Aires, to 10.7% in parts of Peru. Cataract-surgical coverage ranged from good in parts of Brazil to poor in Paraguay, Peru, and Guatemala. Visual outcome after cataract surgery was close to conformity with WHO guidelines in Buenos Aires, where more than 80% of post-surgery eyes had visual acuity of 6/18 (20/60) or better, but ranged between 60% and 79% in most of the other regions, and was less than 60% in Guatemala and Peru.[152]

Social and economic relevance

The cost of cataract surgery depends on the type of procedure, whether it is provided privately or by a government hospital, whether it is provided by out-patient (day care) or in-patient surgery, and on the economic status of people in the region. Because of the high cost of the equipment, phacoemulsification is generally more expensive than ECCE and MSICS.[6] Visual outcomes are variable; they depend upon the underlying condition of the eyes, and the surgical techniques and lens implants used. Regional variations exist due to quality and availability of care.

The restoration of functional vision or improvement in vision possible in most cases has a large social and economic impact; patients may be able to return to paid work or continue their previous jobs, and may not become dependent on support from their family or the wider society. Studies show a sustained improvement to quality of life, financial situation, physical well-being, and mental health. Cataract surgery is one of the most cost-effective health interventions, since its economic benefits considerably exceed the cost of treatment.[153][154]

The 1998 World Health Report estimated 19.34 million people were bilaterally blind due to age-related cataracts, and that cataracts were responsible for 43% of all cases of blindness. This number and proportion were expected to increase due to population growth, and increased life expectancy approximately doubling the number of people older than 60 years. The global increase in blindness from cataract is estimated to be at least five million per year; a figure of 1,000 new cases per million population per year is used for planning purposes. The average outcomes of cataract surgery are improving, and consequently, surgery is being indicated at an earlier stage in cataract progression, increasing the number of operable cases. To reduce the backlog of patients, it is necessary to operate on more people per year than the new cases alone.[155]

As of 1998, the rate of surgeries in economically developed countries was about 4,000 to 6,000 per million population per year, which was sufficient to meet demand. India raised the cataract surgery rate (CSR) to over 3,000, but this was not considered to be sufficient to reduce the backlog. Middle-income countries of Latin America and Asia have CSRs of between 500 and 2,000 per million per year, whereas China, most of Africa, and poor countries of Asia had rates of less than 500. In India and South East Asia, the rate required to keep up with the increase is at least 3,000 per million population per year; in Africa and other parts of the world with smaller percentages of older people, a rate of 2,000 may be sufficient in the short term.[155]

Vision 2020: The Right to Sight, a global initiative of the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB), was intended to reduce or eliminate the main causes of avoidable blindness worldwide by 2020. Programs instituted under Vision 2020 facilitated the planning, development, and implementation of sustainable national eye-care programs, including technical support and advocacy.[156] The IAPB and WHO launched the program on 18 February 1999.[157][158]

The Vision 2020 initiative succeeded in bringing avoidable blindness to the global health agenda. The causes have not been eliminated, but there have been significant changes to their distribution, which have been attributed to global demographic shifts. Remaining challenges to management of avoidable blindness include population size, gender disparities in access to eye-care, and the availability of a professional workforce.[158]

It has been estimated there were 43.3 million blind people in 2020, and 295 million with moderate and severe visual impairment (MSVI), 55% of whom were female. The age-standardised global prevalence in blindness decreased by 28.5% between 1990 and 2020, but the age-standardised prevalence of MSVI increased by 2.5%. Cataract remained the global leading cause of blindness in 2020.[158]

Special populations

Congenital cataracts

_PHIL_4284_lores.jpg.webp)

Congenital cataracts involve a condition of lens opacity that is present at birth, and occur in a broad range of severity; some lens opacities do not progress and are visually insignificant, while others can produce profound visual impairment. Congenital cataracts may be unilateral or bilateral. They can be classified by morphology, presumed or defined genetic cause, presence of specific metabolic disorders, or associated ocular anomalies or systemic findings.[3]

In general, there is greater urgency to remove dense cataracts from very young children because of the risk of amblyopia. For optimal visual development in newborns and young infants, a visually significant unilateral congenital cataract should be detected and removed before the child is six weeks old, while visually significant bilateral congenital cataracts should be removed before 10 weeks.[3] Congenital cataracts that are too small to affect vision will not be removed or treated, but may be monitored by an ophthalmologist throughout the patient's life. Commonly, a patient with small congenital cataracts that do not damage vision will be affected later in life, though this will take decades to occur.[159]

As of 2015, the standard of care for pediatric cataract surgery for children older than two years is primary posterior intraocular lens (IOL) implantation. Primary IOL implantation before the age of seven months is considered to have no advantages over aphakia.[160] According to a 2015 study, primary IOL implantation in the seven-months-to-two-years age groups should be considered in children who require cataract surgery.[160] Research into the possibility of regeneration of infant lenses from lens epithelial cells showed interesting results in a small trial study reported in 2016.[161][162]

Developing world

The capital equipment for phacoemulsification is expensive and requires expert maintenance, and the consumables are also expensive. Quality of outcomes is not sufficiently better than those for manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) to justify the difference in cost in a developing world environment.[6]

Higher risk for operations on separate occasions

Most patients have bilateral cataracts; although surgery in one eye can restore functional vision, second-eye surgery has many advantages, so most patients undergo surgery in each eye on separate days. Operating on both eyes on the same day as separate procedures is known as immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery; this can decrease the number of hospital visits, thus reducing risk of contagion in an epidemic. Immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery also has significant cost savings, and faster visual rehabilitation and neuroadaptation.[Note 14] Another indication is significant cataracts in both eyes of patients for whom two rounds of anaesthesia and surgery would be unsuitable. The risk of simultaneous bilateral complications is low.[163][164]

See also

Medicine portal

Medicine portal Media related to Cataract surgery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cataract surgery at Wikimedia Commons- Africa Cataract Project

- Eye surgery – Surgery performed on the eye or its adnexa