Bahadur Shah I

Mirza Muhammad Mu'azzam (14 October 1643 – 27 February 1712), also known as Bahadur Shah I and Shah Alam I, was the eighth Mughal emperor from 1707 to 1712. He was the second son of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, who he conspired to overthrow in his youth. He was also governor of Agra, Kabul and Lahore and had to face revolts of Rajputs and Sikhs.

| Shah Alam I Bahadur Shah I | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Padishah Al-Sultan Al-Azam | |||||||||||||

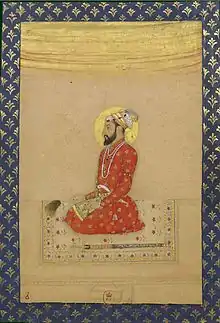

Portrait of Bahadur Shah I, c. 1670 | |||||||||||||

| 8th Mughal Emperor | |||||||||||||

| Reign | 19 June 1707 – 27 February 1712 | ||||||||||||

| Coronation | 15 June 1707 | ||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Azam Shāh (titular) Ālamgīr I | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Jahāndār Shāh | ||||||||||||

| Born | Mirza Muhammad Mu'azzam 14 October 1643 Burhanpur, Mughal Empire (present-day Madhya Pradesh, India) | ||||||||||||

| Died | 27 February 1712 (aged 68) Lahore, Mughal Empire (present-day Pakistan) | ||||||||||||

| Burial | 15 May 1712 | ||||||||||||

| Consort | |||||||||||||

| Wives | |||||||||||||

| Issue |

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| House | House of Babur | ||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Timurid dynasty | ||||||||||||

| Father | Alamgir I | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Nawab Bai | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||

| Mughal emperors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After Aurangzeb's death, Muhammad Azam Shah, his third son by his chief consort declared himself successor, but was shortly defeated in one of the largest battles of India, the Battle of Jajau and overthrown by Bahadur Shah. During the reign of Bahadur Shah, the Rajput states of Jodhpur and Amber were annexed again after they had declared independence a few years prior.

Bahadur Shah also sparked an Islamic controversy in the khutba by inserting the declaration of Ali as wali. His reign was disturbed by several rebellions, the Sikhs under the leadership of Banda Singh Bahadur, Rajputs under Durgadas Rathore and fellow Mughal Kam Bakhsh but all of them except for the rebellion by Banda Singh Bahadur were successfully quelled.

Early life

.jpg.webp)

Bahadur Shah was born as Mu'azzam on 14 October 1643 in Burhanpur. He was the eldest son of prince Muhi al-Din Muhammad, later Mughal emperor Aurganzeb, by his Pothwari wife Nawab Bai, who belonged to the Jarral tribe.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

Shah Jahan's reign

During his grandfather's reign, Shah Jahan, Mu'azzam was appointed vizer of Lahore from 1653 to 1659.[5] In 1663, he replaced Shaista Khan as the governor of Deccan in 1663. Shivaji raided the outskirts of Mughal Deccan's capital Aurangabad while the indolent Mu'azzam did little to prevent it. Enraged at this, Aurangzeb sent his most able commander Raja Jai Singh to defeat Shivaji and here the historic Treaty of Purandar was signed.[9]

Aurangzeb's reign

.jpg.webp)

After Raja Jai Singh I defeated Shivaji at Purandar, Mu'azzam was given charge of the Deccan in May 1667 and was assisted by Maharaja Jaswant Singh.[10]

In 1670, Mu'azzam organised an insurgency to overthrow Aurangzeb and proclaim himself the Mughal emperor. This plan may have been hatched at the instigation of the Marathas, and Mu'azzam's own inclinations and sincerity are difficult to gauge.[11] Aurangzeb learned of the plot and sent Mu'azzam's mother, Begum Nawab Bai, to dissuade him from rebellion. Mu'azzam returned to the Mughal court, where he spent the next several years under Aurangzeb's supervision. However, Mu'azzam again nearly revolted in 1680 over Aurangzeb's scorched earth policy during his suppression of Rajput rebellions. Once again, Aurangzeb dissuaded Mu'azzam with gentleness and watched him with greater vigilance.[12]

For the next seven years, from 1681 to 1687, historian Munis Faruqui describes Mu'azzam as a "grudgingly obedient son".[12]

Rebellion against Aurangzeb

In 1681, Mu'azzam was sent back by Aurangzeb to the Deccan to cut off the retreat of his rebellious half-brother Sultan Muhammad Akbar. According to Faruqui, Mu'azzam deliberately failed in his mission. In 1683, after being ordered by Aurangzeb to march to the Konkan region to prevent the still rebellious Muhammad Akbar from fleeing the country, but again Mu'azzam failed to achieve the assigned goal.[12] In 1687, Aurangzeb ordered Mu'azzam to march against the sultanate of Golconda. Within weeks, the emperor's spies intercepted treasonous messages exchanged between Mu'azzam and Abul Hasan, the ruler of Golconda.[13] This was something which could not be mistaken for incompetence; it was clearly treason.[14] Aurangzeb imprisoned Mu'azzam and his sons, executed his closest followers,[15] ordered his harem "shipped off to faraway Delhi", and dispersed his staff.[16] Aurangzeb forbade Mu'azzam to cut his nails or hair for six months, gave orders depriving him of "good food, or cold water." He was not to meet anybody without his father's prior consent.[15]

Rehabilitation

Around 1694, Aurangzeb rehabilitated Mu'azzam and allowed him "to rebuild his household", rehiring some of his officials.[16] Aurangzeb continued to spy on his son, appointing his men to Mu'azzam's household, sending informants to his harem and choosing his representatives at the imperial court.[17] Mu'azzam and his sons were transferred from the Deccan to north India, and were forbidden to lead military expeditions in the Deccan for the rest of Aurangzeb's reign.[15] In 1695, Aurangzeb sent Mu'azzam to the Punjab to fight the chieftains and subdue a rebellion by the Sikh Guru Gobind Singh. Although the commander imposed "heavy taxation" on the rajas, he thought it necessary to leave the Sikhs undisturbed in their fortified city of Anandpur and refused to wage war against them out of "genuine respect" for their religion.[18] That year Mu'azzam was appointed governor of Akbarabad, and in 1696 he was transferred to Lahore. After the death of Amin Khan, the governor of Kabul he assumed that position in 1699, holding it until his father's death in 1707.[19]

Emperorship

War of succession

Aurangzeb died in 1707, without appointing a crown prince or a designated successor. Mu'azzam was governor of Kabul and his younger half-brothers Muhammad Kam Bakhsh and Muhammad Azam Shah were the governors of the Deccan and Gujarat respectively. All three sons intended to win the crown, and Kam Bakhsh began minting coins in his name. Mu'azzam defeated Azam Shah at the Battle of Jajau in June 1707.[20] Azam Shah and his son Ali Tabar would be killed in the battle.[21] Mu'azzam ascended the Mughal throne at age 64 on 19 June 1707, with the title of Bahadur Shah I.[22] He then marched to the Deccan and defeated and killed Kam Bakhsh in a battle near Hyderabad in January 1708.[23]

Kam Bakhsh's uprising

Muhammad Kam Bakhsh, marched with his soldiers to Bijapur in March 1707. On the news of Aurangzeb's death spread through the city, the city's governor, Sayyid Niyaz Khan surrendered the Bijapur Fort to him without a fight. Ascending the throne of Bijapur, Kam Bakhsh made Ahsan Khan, who served in the army as the bakshi (general of the armed forces), and made his advisor Taqarrub Khan as chief minister[24] and gave himself the title of Padshah Kam Bakhsh-i-Dinpanah (Emperor Kam Bakhsh, Protector of Faith). He then conquered Kulbarga and Wakinkhera.[25]

A rivalry soon broke out between Taqarrub Khan and Ahsan Khan. Ahsan Khan had developed a marketplace in Bijapur where, without permission from Kam Bakhsh, he did not tax the shops. Taqarrub Khan reported it to Kam Bakhsh, who ordered the practise stopped.[25] In May 1707, Kam Bakhsh sent Ahsan Khan to conquer the states of Golkonda and Hyderabad. Although the king of Golconda refused to surrender, Subahdar of Hyderabad, Rustam Dil Khan did so.[26]

Taqarrub Khan made a conspiracy to eliminate Ahsan Khan, alleging that meetings of Ahsan Khan, Saif Khan (Kam Bakhsh's archery teacher), Arsan Khan, Ahmad Khan, Nasir Khan and Rustam Dil Khan (all of them Kam Bakhsh's former teachers and members of the then court) to discuss public business were a conspiracy to assassinate Kam Bakhsh "while on his way to the Friday prayer at the great mosque".[27] After informing Kam Bakhsh of the matter, he invited Rustam Dil Khan for dinner; arrested him en route. Rustam Dil Khan was killed by being crushed under the feet of an elephant. Saif Khan's hands were amputated, and Arshad Khan's tongue was cut off.[28] Ahsan Khan ignored warnings by close friends that Kam Bakhsh would arrest him, and would be imprisoned and his properties seized.[28] In April 1708, Bahadur Shah sent an envoy Maktabar Khan to Kam Bakhsh's court. When Taqarrub Khan told Kam Bakhsh that Maktabar Khan intended to dethrone him,[29] Kam Bakhsh invited the envoy and his entourage to a feast and executed them.[21]

March to the Deccan

In May 1708, Bahadur Shah wrote a letter to Kam Bakhsh in which he warned his brother against proclaiming himself an independent sovereign and began a journey to the Tomb of Aurangzeb to pay his respects to his father.[21] Kam Bakhsh thanked him in a letter, "without either explaining or justifying [his actions]".[30]

Bahadur Shah reached Hyderabad on 28 June 1708, where he learned that Kam Bakhsh had attacked Machhlibandar to seize over three million rupees' worth of treasure hidden in its fort. The subahdar of the province, Jan Sipar Khan, refused to hand over the money.[30] Enraged, Kam Bakhsh confiscated his properties and ordered the recruitment of four thousand soldiers for the attack.[31] In July, the garrison at the Kulbarga Fort declared their independence and garrison leader Daler Khan Bijapuri "reported his desertion from Kam Bakhsh". On 5 November 1708 Bahadur Shah's camp reached Bidar, 67 miles (108 km) north of Hyderabad. Historian William Irvine wrote that as his "camp drew nearer desertions from Kam Bakhsh became more and more frequent". On 1 November, Kam Bakhsh captured Pam Naik's (zamindar, the landlord of Wakinkhera) holdings after Naik abandoned his army.[31]

According to Irvine, more soldiers Kam Bakhsh deserted as the emperor's group neared. When Kam Bakhsh's general told him that his failure to pay his soldiers was the reason for their desertion, he replied: "What need have I of enlisting them? My trust is in God, and whatever is best will happen."[32]

Thinking that Kam Bakhsh might flee to Persia, Bahadur Shah ordered his prime minister Zulfiqar Khan Nusrat Jung to negotiate with Thomas Pitt, the governor of the Madras Presidency, to pay him 200,000 rupees for Kam Bakhsh's capture. On 20 December, Kam Bakhsh was reported to have a cavalry of 2,500 and an infantry of 5,000.[32]

Defeat and death of Kam Bakhsh

On 20 December 1708, Bahadur Shah marched towards Talab-i-Mir Jumla, on the outskirts of Hyderabad, with "three hundred camels, [and] twenty thousand rockets" for war with Kam Baksh. His son Jahandar Shah, was made the commander of the advance guard, but later replaced Khan Zaman. Bahadur Shah reached Hyderabad on 12 January 1709, and prepared his troops. Although Kam Bakhsh had little money and few soldiers left, the royal astrologer had predicted that he would "miraculously" win the battle.[23]

At sunrise the following day, the Mughal army charged towards Kam Bakhsh. His 15,000 troops were divided into two bodies: one led by Mumin Khan, assisted by Rafi-ush-Shan and Jahan Shah, and the second under Zulfiqar Khan Nusrat Jung. Two hours later Kam Bakhsh's camp was surrounded, and Zulfiqar Khan impatiently attacked him with his "small force".[33]

With his soldiers outnumbered and unable to resist the attack, Kam Bakhsh joined the battle and shot two quivers of arrows at his opponents. According to Irvine, when he was "weakened by loss of blood", Bahadur Shah took him and his son Bariqullah prisoner. A dispute arose between Mumin Khan and Zulfikar Khan Nusrat Jung over who had captured them, with Rafi-us-Shan ruling in favour of the latter.[34] Kam Bakhsh was brought by palanquin to the emperor's camp, where he died the next morning.[35]

Amber

After ascending the throne, Bahadur Shah made plans to annex Rajput kingdoms who declared independence after Aurangzeb's death. On 10 November, he began his march to Kingdom of Amber in Rajputana. He visited the Tomb of Salim Chishti in Fatehpur Sikri on 21 November. In the meantime, Bahadur Shah's aide Mihrab Khan was ordered to take possession of Jodhpur.[36] Bahadur Shah reached Amber on 20 January 1708. Though the monarch of the kingdom was Sawai Jai Singh, his brother Bijai Singh resented his rule. Bahadur Shah ruled that because of the dispute, the region would become part of the Mughal empire and the city was renamed as Islamabad. Jai Singh's goods and properties were confiscated on the pretext that he supported Bahadur Shah's brother Azam Shah during the succession war.[36] Bijai Singh was made the governor of Amber on 30 April 1708. Bahadur Shah gave him the title of Mirza Rajah, and he received gifts valued at 100,000 rupees. Amber passed into Mughal hands without a war.[37]

Jodhpur

Jaswant Singh, the leader of the Rathore dynasty, was the Maharaja of the Kingdom of Marwar during Aurangzeb's reign. During the war of succession after Shah Jahan, he had backed Aurangzeb's older brother Dara Shikoh. After Dara Shikoh's defeat and execution by Aurangzeb, Jaswant Singh was pardoned and appointed the governor of Kabul. He died on 18 December 1678, with no male children but two pregnant wives.

After the birth of Ajit Singh to Rani Jadav Jaskumvar, Aurangzeb ordered he be brought to Delhi along with Jaswant Singh's widows. Aurangzeb intended to directly annex Marwar into the Mughal empire. The Rajput general Durgadas Rathore, who had ambitions of retaking Jodhpur from the Mughals, fought a war to prevent Aurangzeb getting hold of Ajit Singh; he tore through Delhi with his men and successfully escorted the Prince and the widows to Jodhpur.[38] After Aurangzeb's death, during Azam Shah's brief reign, Ajit Singh marched to Jodhpur and took it from Mughal rule.[39]

In Amber, Bahadur Shah announced his intention to march to Jodhpur when Mihrab Khan defeated Ajit Singh at Mairtha, and he reached the town on 21 February 1708. His men were sent to bring Ajit Singh to the city for an interview, where Ajit Singh received "special robes of honour" and a jewelled scarf.[40] Bahadur Shah then headed towards Ajmer and reached the city on 24 March, where he visited the Dargah Sharif.[41]

Udaipur

The Kingdom of Mewar, under Maharana Amar Singh I, had submitted to Mughal rule in 1615, during Jahangir's reign. However, the Sisodias declared their independence after Aurangzeb's death in 1707.[40]

While in Jodhpur, Bahadur Shah got the news that the Maharana Amar Singh II had fled Udaipur to hide in the hills. His messengers gave him the message that Amar Singh got "afraid" by the happenings in Amber and Jodhpur and thought that his kingdom would also be annexed by the Mughals once again.[41] According to the Bahadur Shah Nama chronicle, because of this incident the emperor called Amar Singh an "unbeliever".[41] Bahadur Shah waged war against the king until Muhammad Kam Bakhsh's insurgency diverted him southward.[41]

Rajput Rebellion

While the emperor was on his way to Deccan to punish Muhammad Kam Bakhsh, the three Rajput Raja's of Amber, Udaipur and Jodhpur made a joint resistance to the Mughals. The Rajputs first expelled the Mughal commandants of Jodhpur and Hindaun-Bayana and recovered Amber by a night attack. They next killed Sayyid Hussain Khan Barha, the commandant of Mewat and many other officers (September, 1708). The emperor, then in the Deccan had to patch up a truce by restoring Ajit Singh and Jai Singh to the Mughal service.[42]

Sikh rebellion

Bahadur Shah, upon hearing of the uprising led by Banda Bahadur in Punjab only a year after Guru Gobind Singh's death, left the Deccan for the north. The Sikhs started moving cautiously towards Delhi and entered the sarkar in Khanda where they started preparation for a military campaign. They stormed Sonipat and Samana in November 1709 and defeated the faujdar in the Battle of Sonipat and Battle of Samana whilst sacking the town. Before taking Sirhind in the Battle of Chappar Chiri, Banda Bahadur captured Shahabad, Sadhaura and Banur. Before Bahadur Shah's arrival in December, Banda Bahadur had captured the sarkar of Sirhind, several parganas of the sarkar of Hissar, and had invaded the sarkar of Saharanpur.[43]

After the victory at Sirhind, the Sikhs turned towards the Gangetic Doab. With trouble arising in a pargana of Deoband and Sikh converts complaining of imprisonment and persecution by the faujdar Jalal Khan, Banda Bahadur marched on Saharanpur on the way to Jalalabad. The faujdar of Saharanpur, Ali Hamid Khan, fled to Delhi while the Sikhs defeated the defenders and reduced the town. They next attacked Behat whose Pirzadas were notorious for anti-Hindu acts, especially slaughtering cows. The town was sacked and the Pirzadas killed. The Sikhs then marched to Jalalabad and Banda asked Jalal Khan to surrender and release the Sikh prisoners, but the faujdar refused. They came to Nanauta on 21 July 1710 and defeated the local Sheikhzadas, who had put up a gallant defence but ultimately submitted to Banda Bahadur's superior forces.[44] The Sikhs then besieged Jalalabad but withdrew to Jalandhar Doab due to the flooding in the Krishna River.[45][46]

The Sikhs tried to oust the Mughals from the regions of Jalandhar and Amritsar. They called on Shamas Khan, the Faujdar of Jalandhar, to effect reforms and hand over the treasury. Shamas Khan pretended submission and later started attacking them. He appealed to Muslims in name of religion and declared a jihad against the Sikhs. The Sikhs, being outnumbered, withdrew to Rahon and captured its fort after defeating the Mughals in the Battle of Rahon on 12 October 1710. At Amritsar, about 8,000 Sikhs assembled and captured Majha and Riarki of central Punjab. They also attacked Lahore, where the mullahs declared a jihad against them with the governor not confronting the Sikhs. The ghazis were defeated by the Sikhs.[45][46]

Sikhs used their newly established power to remove Mughal officials and replace them with Sikhs.[45] Banda made his capital at Lohgarh, where he established a mint.[47] He abolished the mughal Zamindari system and gave the cultivators proprietorship of their own land.[48]

Efforts at suppression

Bahadur Shah signed peace treaties with Ajit Singh of Jodhpur, and Man Singh of Amber before turning to fight Banda Bahadur. He also ordered the Nawab of Awadh Asaf-ud-Daula, provincial governor Khan-i-Durrani, Moradabad faujdar Muhammad Amin Khan Chin, Delhi subahdar Asad Khan and Jammu faujdar Wazid Khan to accompany him into battle.

Bahadur Shah left Ajmer for the Punjab on 17 June 1710, mobilising groups opposed to Banda Bahadur on the way.[49] When he learned about Bahadur Shah's plans, Banda Bahadur unsuccessfully appealed to Ajit Singh and Man Singh for help.[49] In the meantime, Bahadur Shah had reoccupied Sonipat, Kaithal and Panipat en route. In October, his commander Khanzada Nawab Feroz Khan wrote to him that he had "chopped three hundred heads of rebels"; Khan sent them to the emperor, who displayed them mounted on spears.[50]

On 1 November 1710 the emperor reached the city of Karnal, where Mughal cartographer Rustam Dil Khan gave him a map of Thanesar and Sirhind. Six days later, a small group of Sikhs were defeated at Mewati and Banswal.[50] The city of Sirhind fell to the Mughals on 7 December; its besieger, general Muhammad Amin Khan Turani, gave the emperor a golden key ring commemorating the victory. After failing to recapture Sadaura, Bahadur Shah marched towards Lohgarh, where Banda Bahadur was hiding. On 30 November he attacked the Lohgarh fort, capturing three guns, matchlocks and three trenches from the rebels. With little ammunition left, Banda Bahadur and a "few hundred of his followers fled".[51] His follower, Gulab Singh (who was "dressed like" Bahadur), entered the fight and was killed.[51] The emperor issued orders to the rulers of Kumaon and Srinagar that if Bahadur tried to enter their province, he should be "sent to the Emperor".[52]

Suspecting that Banda Bahadur was allied with Bhup Prakash, the king of Nahan, the emperor had Bhup Prakash imprisoned in January 1711; his mother begged in vain for his release. After she sent him captured followers of Bahadur, he ordered that "ornaments worth 100,000 rupees should be manufactured" for her, and Prakash was released a month later.[52] Shukan Khan Bahadur and Himmet Diler Khan were sent to Lahore to end Banda Bahadur's rebellion, and their unsuccessful attempt was reinforced by a garrison of five thousand soldiers. Bahadur Shah also pressed Rustam Dil Khan and Muhammad Amin Khan to join them.[53]

Banda Bahadur was hiding in Alhalab, 7 miles (11 km) from Lahore. When Mughal workers came to repair a bridge in the village, his followers disinformed them that he was preparing to attack Delhi via Ajmer. Banda Bahadur received soldiers from village ruler Ram Chand for his march against the Mughals, and besieged Fatehabad in April 1711. After learning from messenger Rustan Jung that he had crossed the Ravi River, the emperor attacked with artillery led by Isa Khan.[54] In the July battle, Banda Bahadur was defeated and fled to the Jammu hills. Forces led by Isa Khan Main and Muhammad Amin Khan followed but failed to capture him. The emperor issued an edict to the zamindars (landlord) of Jammu to take the Sikh captive if possible.[55]

Banda Bahadur was attacked by Muhammad Amin Khan at the river Satluj, escaping to the Garhwal hills. Finding him "invincible", the emperor went to Ajit Singh and Jai Singh for help. In October 1711, a joint Mughal-Rajput force marched towards Sadaura. Bahadur escaped the ensuing siege, this time taking refuge at Kulu in present-day Himachal Pradesh.[56]

Khutba controversy

After ascending the throne, emperor Bahadur Shah converted to Shia Islam and altered the public prayer (or khutba) for the monarch said every Friday by giving the title wali to Ali, the fourth caliph and the first Shi'a Imam. Because of this, the citizens of Lahore resented reciting the khutba.[57]

To solve the problem, Bahadur Shah went to Lahore in September 1711 and had discussions with Haji Yar Muhammad, Muhammad Murad and "other well-known men". At their meeting, he read "books of authority" to justify using the word wasi. He had a heated argument with Yar Muhammad, saying that martyrdom by a king was the only thing he wanted. Yar Muhammad (supported by the emperor's son, Azim-ush-Shan) recruited troops against Shah, but no war was fought.[57] He held the khatib (chief reciter) at the Badshahi Mosque responsible for the matter, and had him arrested. On 2 October, although the army was deployed at the mosque the old khutba (which did not call Ali "wasi") was read.[58]

Death

According to historian William Irvine, the emperor was in Lahore in January 1712 when his "health failed". On 24 February he made his final public appearance,[59] and died during the night of 27–28 February; according to Mughal noble Kamwar Khan, of "enlargement of the spleen". On 11 April, his body was sent to Delhi under the supervision of his widow Mihr-Parwar and Chin Qilich Khan. He was buried on 15 May in the courtyard of the Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) in Mehrauli, which he built near the dargah of Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki.[60]

He was succeeded by his son Jahandar Shah who ruled until 1713.[61]

Coins

Emperor Bahadur Shah issued gold, silver and copper coins, although his predecessors' coins were also used to pay government officials and in commerce. Copper coins from Aurangzeb's reign were re-minted with his name.[62] Unlike the other Mughal emperors, his coins did not use his name in a couplet; poet Danishmand Khan composed two lines for the coins, but they were not approved.[63]

Silver rupee from Azimabad, 1708

Silver rupee from Azimabad, 1708

Silver rupee from Shahjahanabad, 1708

Silver rupee from Shahjahanabad, 1708

Personal life

Name, title and lineage

His full name, including his titles, was "Abul-nasr Sayyid Qutb-ud-din Muhammad Shah Alam Bahadur Shah Badshah". After his death, contemporary historians began calling him "Khuld-Manzil" (Departed to Paradise).[60] He was the only Mughal emperor to have the title Sayyid, used by descendants of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. According to William Irvine, his maternal grandfather was Sayyid Shah Mir (whose daughter, Nawab Bai Ji, married Aurangzeb).

Children

| Name | Born | Died | Mother | Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jahandar Shah | 1661 | 1713 | Nizam Bai | Alamgir II, Izz-ud-din |

| Azz-ud-din | 1664 | Infancy | Nizam Bai | None |

| Azim-ush-Shan | 1665 | 1712 | Amrita Bai Sahiba | Muhammad Karim, Farrukhsiyar, Humayun Bakht, Ruh-ul-Quds, Ahsan-ullah |

| Daulat-Afza | 1670 | 1689 | Amrita Bai Sahiba | None |

| Rafi-ush-Shan | 1671 | 1712 | Nur-un-nissa Begum | Shah Jahan II, Rafi ud-Darajat, Muhammad Ibrahim |

| Jahan Shah | 1674 | 1712 | Dilruba | Farkhunda Akhtar, Muhammad Shah |

| Muhammad Humayun | 1678 | Infancy | - | None |

| Dahr Afruz Banu Begum | 1663 | 1703 | - |

cavty |

Depictions

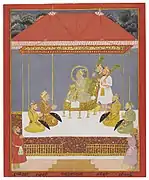

Emperor Bahadur Shah I with his sons

Emperor Bahadur Shah I with his sons Bahadur Shah enthroned outdoors

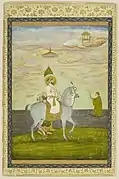

Bahadur Shah enthroned outdoors Bahadur Shah I, post coronation painting featuring Mughal symbols

Bahadur Shah I, post coronation painting featuring Mughal symbols An elderly Bahadur Shah I

An elderly Bahadur Shah I

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Bahadur Shah I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- From 1707, he developed tafzili tendencies

- Irvine, William (1991) [First published 1921]. Later Mughals. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 141.

- Faruqui 2012, p. 303.

- Epilogue, Vol 3, Issue 11. p. 46.

- Manucci 1907, p. 54.

- Irvine 1904, p. 2.

- Sarkar 1912, p. 61.

- Irvine 1904, p. 136.

- "History | Rajouri, Government of Jammu and Kashmir | India".

- Richards 1905, p. 209.

- Kulkarni 1979, p. 336.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1920). Shivaji and his times. University of California Libraries. London, New York, Longmans, Green and co. p. 192.

- Faruqui 2012, p. 305.

- Irvine 1904, p. 3.

- Faruqui 2012, p. 306.

- Faruqui 2012, p. 307.

- Faruqui 2012, p. 285.

- Faruqui 2012, p. 286.

- Singh 2010, p. 55.

- Irvine 1904, p. 4.

- Puri 2003, p. 198.

- Irvine 1904, p. 57.

- Puri 2003, p. 199.

- Irvine 1904, p. 61.

- Irvine 1904, p. 50.

- Irvine 1904, p. 51.

- Irvine 1904, p. 52.

- Irvine 1904, p. 53.

- Irvine 1904, p. 55.

- Irvine 1904, p. 56.

- Irvine 1904, p. 58.

- Irvine 1904, p. 59.

- Irvine 1904, p. 60.

- Irvine 1904, p. 62.

- Irvine 1904, p. 63.

- Irvine 1904, p. 64.

- Irvine 1904, p. 46.

- Irvine 1904, p. 47.

- Irvine 1904, p. 44.

- Irvine 1904, p. 45.

- Irvine 1904, p. 48.

- Irvine 1904, p. 49.

- Haig 1971, p. 322.

- Grewal 1998, pp. 82–83.

- Surjit Singh Gandhi (1980). Struggle of the Sikhs for Sovereignty. p. 12.

- Singh 1927, p. 9.

- Singh & Singh 1999, pp. 86–88.

- Grewal 1998, p. 83.

- Jawandha 2010, p. 81.

- Singh 2003, p. 58.

- Singh 2003, p. 59.

- Singh 2003, p. 60.

- Singh 2003, p. 61.

- Singh 2003, p. 62.

- Singh 2003, p. 63.

- Singh 2003, p. 64.

- Singh 2003, p. 66.

- Irvine 1904, p. 130.

- Irvine 1904, p. 131.

- Irvine 1904, p. 133.

- Irvine 1904, p. 135.

- Irvine 1904, p. 158.

- Irvine 1904, p. 141.

- Irvine 1904, p. 140.

- Irvine 1904, p. 143.

- Irvine 1904, p. 144.

- Mehta 1984, p. 418.

- Sarker 2007, p. 187.

- Lal 1989, p. xi.

- Thackeray & Findling 2012, p. 254.

- Massy 1890, p. 396.

References

- Faruqui, Munis D. (2012), The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-02217-1

- Grewal, J. S. (1998) [1990], The Sikhs of the Punjab, The New Cambridge History of India, vol. II.3 (revised ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-63764-0

- Haig, Wolseley (1971), The Cambridge History of India, vol. 4, Chand & Co.

- Irvine, William (1904), The Later Mughals, Low Price Publications, ISBN 81-7536-406-8

- Jawandha, Nahar (2010), Glimpses of Sikhism, New Delhi: Sanbun Publishers, p. 81, ISBN 9789380213255

- Kulkarni, G. T. (1979), "Shivaji-Mughal Relations (1669-80): Gleanings from some unpublished Persian records", Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Indian History Congress, 40: 336–341, JSTOR 44141973

- Manucci, Niccolao (1907). Storia Do Mogor: Or, Mogul India, 1653-1708 - Volume 2. J. Murray.

- Lal, Muni (1989), Mini Mughals, Konark Publishers, ISBN 9788122001747

- Massy, Charles Francis (1890), Chiefs and Families of Note in the Delhi, Jalandhar, Peshawar and Derajat Divisions of the Panjab, Allahabad: The Pioneer Press, p. 396

- Mehta, J. L. (1984) [First published 1981], Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India, vol. II (2nd ed.), Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd, ISBN 978-81-207-1015-3, OCLC 1008395679

- Puri, B.N. (2003), Comprehensive history of medieval India, Sterling Publishers, ISBN 978-81-207-2508-9

- Richards, John F. (1905), The New Cambridge History of India: Part I, Volume V - The Mughal Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521566032

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1912). History of Aurangzib mainly based on Persian sources: Volume 1 - Reign of Shah Jahan. M.C. Sarkar & sons, Calcutta.

- Sarker, Kobita (2007), Shah Jahan and his paradise on earth: the story of Shah Jahan's creations in Agra and Shahjahanabad in the golden days of the Mughals, K.P. Bagchi & Co., ISBN 978-81-7074-300-2

- Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta (1952), History of India, vol. 3, Viswanathan

- Singh, Gurbaksh (1927), The Khalsa Generals, Canadian Sikh Study & Teaching Society, ISBN 0969409249

- Singh, Patwant (2010), The Sikhs, Rupa Publications, ISBN 978-81-7167-624-8

- Singh, Raj Pal (2003), The Sikhs : Their Journey of Five Hundred Years, Pentagon Press, ISBN 978-81-86505-46-5

- Singh, Teja; Singh, Ganda (1999), A Short History of the Sikhs: 1469–1765, Patiala: Publication Bureau, Punjabi University, ISBN 9788173800078

- Thackeray, Frank W.; Findling, John E. (2012), Events That Formed the Modern World, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-901-1