Ptolemy V Epiphanes

Ptolemy V Epiphanes Eucharistos[note 1][3] (Greek: Πτολεμαῖος Ἐπιφανής Εὐχάριστος, Ptolemaĩos Epiphanḗs Eucharistos "Ptolemy the Manifest, the Beneficent"; 9 October 210–September 180 BC) was the King of Ptolemaic Egypt from July or August 204 BC until his death in 180 BC.

| Ptolemy V Epiphanes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Greek: Πτολεμαῖος Ἐπιφανής Ancient Egyptian: Iwaennetjerwymerwyitu Seteppah Userkare Sekhem-ankhamun[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tetradrachm issued c. 200 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of the Ptolemaic Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | July/August 204–September 180 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ptolemy IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Ptolemy VI | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Cleopatra I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Ptolemy VI Ptolemy VIII Cleopatra II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Ptolemy IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Arsinoe III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 9 October 210 BC[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | September 180 BC (aged 29)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Alexandria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ptolemaic dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ptolemy V, the son of Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III, inherited the throne at the age of five when his parents died in suspicious circumstances. The new regent, Agathocles, was widely reviled and was toppled by a revolution in 202 BC, but the series of regents who followed proved incompetent and the kingdom was paralysed. The Seleucid king Antiochus III and the Antigonid king Philip V took advantage of the kingdom's weakness to begin the Fifth Syrian War (202–196 BC), in which the Ptolemies lost all their territories in Asia Minor and the Levant, as well as most of their influence in the Aegean Sea. Simultaneously, Ptolemy V faced a widespread Egyptian revolt (206–185 BC) led by the self-proclaimed pharaohs Horwennefer and Ankhwennefer, which resulted in the loss of most of Upper Egypt and parts of Lower Egypt as well.

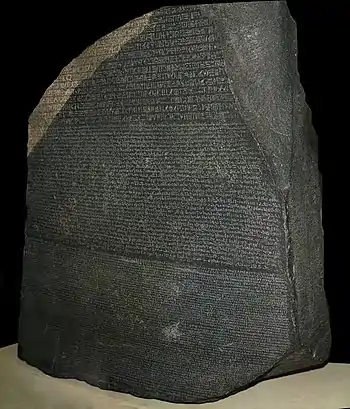

Ptolemy V came of age in 196 BC and was crowned as pharaoh in Memphis, an occasion commemorated by the creation of the Rosetta Stone. After this, he made peace with Antiochus III and married the daughter of Antiochus III Cleopatra I in 194/3 BC. This outraged the Romans, who had entered into hostilities with Antiochus III partially on Ptolemy V's behalf, and after their victory they distributed the old Ptolemaic territories in Asia Minor to Pergamum and Rhodes rather than returning them to Egypt. However, Ptolemaic forces steadily reconquered the south of the country, bringing all of Upper Egypt back under Ptolemaic control in 186 BC. In his last years, Ptolemy V began manoeuvering for renewed warfare with the Seleucid empire, but these plans were cut short by his sudden death in 180 BC, allegedly poisoned by courtiers worried about the cost of the war.

Ptolemy V's reign saw greatly increased prominence of courtiers and the Egyptian priestly elite in Ptolemaic political life, a pattern that would continue for most of the rest of the kingdom's existence. It also marked the collapse of Ptolemaic power in the wider Mediterranean region. Arthur Eckstein has argued that this collapse sparked the "power transition crisis" that led to the Roman conquest of the eastern Mediterranean.[4]

Background and early life

Ptolemy V was the only child of Ptolemy IV and his sister-wife Arsinoe III. The couple had come to power relatively young and ancient historiography remembered Ptolemy IV as being given over to luxury and ceremony, while leaving the government of Egypt largely to two courtiers, Sosibius and Agathocles (the latter being the brother of Ptolemy IV's concubine Agathoclea). In his early reign, Ptolemy IV successfully defeated the rival Seleucid empire in the Fourth Syrian War (219-217 BC), successfully preventing the Seleucid king Antiochus III from seizing Coele Syria for himself. His later reign, however, was troubled by native Egyptian revolts. Between 206 and 205 BC, Ptolemy IV lost control of Upper Egypt to the self-styled pharaoh Hugronaphor.[5]

Ptolemy V was born in 210 BC, possibly on 9 October. He was made co-regent with his father shortly thereafter, probably on 30 November.[note 2][6] In July or August of 204 BC, when Ptolemy V was five years old, his father and mother died in mysterious circumstances. It appears that there was a fire in the palace that killed Ptolemy IV, but it is unclear whether Arsinoe III also perished in this fire or was murdered afterwards to prevent her from becoming regent.[6]

Regencies

Regency of Agathocles (204–203 BC)

An uncertain amount of time elapsed after the death of Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III (perhaps a week) during which Sosibius and Agathocles kept their deaths secret. Some time before September 204 BC,[2] the royal bodyguard and army officers were gathered at the royal palace and Sosibius announced the death of the ruling couple and presented the young Ptolemy V to be acclaimed as king, wrapping the diadem around his head. Sosibius read out Ptolemy IV's will, which made Sosibius and Agathocles regents and placed Ptolemy V in the personal care of his mistress Agathoclea and her mother Oenanthe. Polybius thought that this will was a forgery produced by Sosibius and Agathocles themselves and modern scholars tend to agree with him. Sosibius is not heard of again after this event and it is generally assumed that he died. Hölbl suggests that the loss of his acumen was fatal to the regency.[7][8]

Agathocles took a number of actions to solidify the new regime. Two months' pay were granted to the soldiers in Alexandria. Prominent aristocrats were dispatched overseas - to secure recognition of the succession from foreign powers and to prevent the aristocrats from challenging Agathocles for supremacy at home. Philammon, said to have carried out the murder of Arsinoe III, was sent to Cyrene as governor in order to assert Ptolemaic rule there. Pelops, governor of Cyprus, was sent to Antiochus III to ask him to continue to respect the peace treaty made with Ptolemy IV at the end of the Fourth Syrian War. Ptolemy, Sosibius' son, was sent to Philip V of Macedon to attempt to arrange an alliance against Antiochus III and a marriage between Ptolemy V and one of Philip V's daughters. Ptolemy of Megalopolis was sent to Rome, probably seeking support against Aniochus III.[9] These missions were failures. Over the following year, Antiochus III seized Ptolemaic territory in Caria, including the city of Amyzon, and by late 203 BC he and Philip V had made a secret agreement to divide the Ptolemaic territories between themselves.[10][8] War with Antiochus III was expected - Agathocles had also sent an embassy under Scopas the Aetolian to hire mercenaries in Greece in preparation for a conflict, although Polybius claims that his true purpose was to replace the Ptolemaic troops with mercenaries loyal to him.[11]

Alexandrian revolution (203–202 BC)

Agathocles and Agathoclea had already been unpopular before Ptolemy IV's death. This unpopularity was exacerbated by the widespread belief that they had been responsible for the death of Arsinoe III and a string of extrajudicial murders of prominent courtiers. Opposition crystallised around the figure of Tlepolemus, the general in charge of Pelusium, whose mother-in-law had been arrested and publicly shamed by Agathocles. In October 203 BC,[2] when Agathocles gathered the palace guard and army to hear a proclamation in advance of the royal coronation, the assembled troops began to insult him and he barely escaped alive.[12] Shortly after this, Agathocles had Moeragenes, one of the royal bodyguards, arrested on suspicion of ties to Tlepolemus and had him stripped and tortured. He escaped and convinced the army to go into active revolt. After an altercation with Oenanthe (the mother of the regent and his sister) at the temple of Demeter, the Alexandrian women joined the revolt as well. Overnight, the populace besieged the palace calling for the king to be brought to them. The army entered at dawn and Agathocles offered to surrender. Ptolemy V, now about seven years old, was taken from Agathocles and presented to the people on horseback in the stadium. In response to the crowd's demands, Sosibius, son of Sosibius, persuaded Ptolemy V to agree to the execution of his mother's killers. Agathocles and his family were then dragged into the stadium and killed by the mob.[13][14][8]

Tlepolemus arrived in Alexandria immediately after these events and was appointed regent. He and Sosibius, son of Sosibius were also made Ptolemy V's legal guardians. Popular opinion soon turned against Tlepolemus, who was considered to spend too much time sparring and drinking with the soldiers and to have given too much money to embassies from the cities of mainland Greece. Ptolemy, son of Sosibius attempted to set his brother Sosibius up in opposition to Tlepolemus, but the plan was discovered and Sosibius was dismissed as guardian.[15]

Fifth Syrian War (202–196 BC)

Since his defeat by Ptolemy IV in the Fourth Syrian War in 217 BC, Antiochus III had been waiting for an opportunity to avenge himself. He had begun seizing Ptolemaic territory in western Asia Minor in 203 BC and made a pact with Philip V of Macedon to divide the Ptolemaic possessions between themselves late in that year.[10] In 202 BC, Antiochus III invaded Coele-Syria and seized Damascus. Tlepolemus responded by sending an embassy to Rome begging for help.[16] At some point over the winter, Tlepolemus was replaced as regent by Aristomenes, a member of the bodyguard who had been instrumental in the seizure of young Ptolemy V from Agathocles.[8]

In 201 BC, Antiochus III invaded Palestine and eventually captured Gaza. The Ptolemaic governor of Coele-Syria, Ptolemy, defected to Antiochus III, bringing his territory with him and remaining its governor. Meanwhile, Philip V seized Samos and invaded Caria. This led to conflict with Rhodes and the Attalids who also sent embassies to Rome. In summer 200 BC Philip V conquered the Ptolemaic possessions and independent cities in Thrace and the Hellespont and the Romans intervened, starting the Second Macedonian War (200-197 BC).[17]

The Ptolemaic general Scopas led a successful reconquest of Palestine over the winter of 201/200,[18] but Antiochus III invaded again in 200 BC and defeated him decisively at the Battle of Panium.[19] A Roman embassy made an ineffectual attempt to broker a peace between Ptolemy V and Antiochus III, but largely abandoned the Egyptians to their fate.[20] Scopas was besieged at Sidon over the winter, but had to surrender at the beginning of summer 199 BC. He was sent off to his homeland of Aetolia to recruit troops in case Antiochus III moved on to attack Egypt itself.[21] Instead, Antiochus III spent 198 BC solidifying his conquest of Coele-Syria and Judea, which would never again return to Ptolemaic control. In 197 BC, Antiochus III turned on the Ptolemaic territories remaining in Asia Minor, conquering their cities in Cilicia,[22] as well as several of their cities in Lycia and Ionia, notably Xanthos, Telmessus, and Ephesus.[23][17]

The Egyptian Revolt (204–196 BC)

A revolt had broken out in Upper Egypt under the native pharaoh Hugronaphor (Horwennefer) in the last years of Ptolemy IV's reign and Thebes had been lost in November 205 BC. The conflict continued throughout the infighting of Ptolemy V's early reign and during the Fifth Syrian War. Hugronaphor was succeeded by or changed his name to Ankhmakis (Ankhwennefer) in late 199 BC.[24][25]

Shortly after this, Ptolemy V launched a massive southern campaign, besieging Abydos in August 199 BC and regaining Thebes from late 199 BC until early 198 BC. The next year, however, a second group of rebels in the Nile Delta, who were linked to Ankhmakis in some way that is not entirely clear, captured the city of Lycopolis near Busiris and invested themselves there. After a siege, the Ptolemaic forces regained control of the city. The rebel leaders were taken to Memphis and publicly executed on 26 March 196 BC, during the feast celebrating Ptolemy V's coronation as pharaoh.[26][24]

Personal reign

Coronation

By 197 BC the dismal Ptolemaic performance in the war against Antiochus III had completely eroded Aristomenes' authority as regent. Around October or November 197 BC, the Ptolemaic governor of Cyprus, Polycrates of Argos, came to Alexandria, and arranged for Ptolemy V to be declared an adult with a ceremony known as an anacleteria, even though he was only thirteen years old. Polybius writes that Ptolemy V's courtiers "thought that the kingdom would gain a certain degree of firmness and a fresh impulse towards prosperity, if it were known that the king had assumed the independent direction of the government."[27] He was crowned in Memphis by the High Priest of Ptah on 26 March 196. Polycrates now became the chief minister in Alexandria and Aristomenes was forced to commit suicide in the following years.[28][17]

The day after Ptolemy V's coronation, a synod of priests from all over Egypt who had gathered for the event passed the Memphis decree. The decree was inscribed on stelae, and two of these stelae survive: the Nubayrah Stele and the famous Rosetta Stone. This decree praises Ptolemy V's benefactions for the people of Egypt, recounts his victory over the rebels at Lycopolis, and remits a number of taxes on the temples of Egypt. The decree has been interpreted as a reward for the priests' support of Ptolemy V against the rebels.[29] Günther Hölbl instead interprets the decree as a sign of the priests' increased power. In his view, the priests asserted their right to the remission of taxes, aware that Ptolemy V was relying more heavily on their support than his predecessors had, and he had no choice but to concede.[30]

Peace with Antiochus III

After the Romans decisively defeated Philip V at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC, they turned their attention to Antiochus III, whose troops had crossed the Hellespont and entered Thrace. In late 196 or early 195 BC Lucius Cornelius Lentulus met with the Syrian king and, among other things, demanded that Antiochus III return everything he had conquered from Ptolemy V. However, Antiochus announced that he had already begun peace negotiations with Egypt and the Romans departed without achieving anything.[31] Antiochus then concluded peace with Ptolemy, engaging him to his own daughter Cleopatra I. In winter of 194/193 BC, the sixteen-year old Ptolemy V married Cleopatra I, who was somewhere between 14 and 23 years old. Symbolically, Antiochus held the wedding that sealed his conquest of Coele-Syria at Raphia, the site of his great defeat at the hands of Ptolemy IV.[32][33]

End of the Egyptian Revolt (196–185 BC)

In the mid 190s BC, Ankhmakis made some sort of agreement with King Adikhalamani of Meroe. In return for the southern Egyptian city of Syene, Adikhalamani provided some sort of aid which enabled Ankhmakis to recapture Thebes by autumn 195 BC. Violent battles between the forces of Ptolemy V and Ankhmakis took place around Asyut. In late 191 or early 190 BC, papyrus records indicate that Thebes was once again under Ptolemy V's control. The Ptolemaic general Comanus led this reconquest. In 187 BC, Adikhalamani pulled out of Syene and abandoned his support for Ankhmakis. The priests who had supported Ankhmakis accompanied his troops back to Meroe. On 27 August 186 BC, Ankhmakis and his son led a last-ditch attack on Thebes, but were defeated by Comanus. This victory re-established Ptolemaic rule in Upper Egypt, as well as the Triakontaschoinos. In temples in the region, inscriptions with the names of the Meroitic kings who had ruled the region since 206 BC were scratched out.[24]

Ankhmakis was taken to Alexandria and executed on 6 September 186 BC. Soon after, an official synod of priests gathered in the city and passed a decree, known today as the Philensis II decree, in which Ankhmakis was denounced for rebellion and various other crimes against humanity and the gods. A month later, on 9 October 186 BC, Ptolemy V issued the 'Amnesty Decree', which required all fugitives and refugees to return to their homes and pardoned them for any crimes committed before September 186 BC (except temple robbery). This was intended to restore land to cultivation that had been abandoned during the prolonged period of warfare. To prevent further revolts in the south, a new military governorship of Upper Egypt, the epistrategos, was created, with Comanus serving in the role from 187 BC. Greek soldiers were settled in villages and cities in the south, to act as a garrison force in the event of further unrest.[24]

The rebels in Lower Egypt still continued to fight on. In 185 BC, the general Polycrates of Argos succeeded in suppressing the rebellion. He promised the leaders of the rebellion that they would be treated generously if they surrendered. Trusting this, they voluntarily went to Sais in October 185 BC, where they were stripped naked, forced to drag carts through the city, and then tortured to death.[34] Whether Polycrates or Ptolemy V was responsible for this duplicitous cruelty is disputed.[24]

Foreign policy after the Fifth Syrian War (194/3–180 BC)

After the end of the Fifth Syrian War, Ptolemy V made an effort to reassert Ptolemaic power on the world stage and to claw back some of the territories lost to the Seleucids, with very little success. When the Roman–Seleucid War broke out in 192 BC, Ptolemy V sent an embassy to Rome offering financial and military support, but the Senate refused it, apparently annoyed about the separate peace that Ptolemy V had made with Antiochus III in 194/3 BC.[35] Another embassy to Rome in 191 BC, congratulating the Senate on the Roman victory at the Battle of Thermopylae, was entirely ignored.[36] At the end of the war in 188 BC, when the Romans imposed the Treaty of Apamea on Antiochus III, which forced him to give up all his territory in Asia Minor, they did not return the former Ptolemaic holdings in the region to Ptolemy V, but awarded them to Pergamum and Rhodes instead.[37][38]

When Antiochus III died in 187 BC and was succeeded by his son Seleucus IV, Ptolemy V began preparations for a renewed war to recapture Coele-Syria. Ptolemy V's childhood friend, the eunuch Aristonicus, was sent to Greece to recruit mercenaries in 185 BC.[39] At the same time, the king revived the alliances that his grandfather Ptolemy III had maintained with the Achaean League, presenting the League with monetary gifts and promising them ships as well.[40] To raise his profile in Greece, Ptolemy V also entered a chariot team in the Panathenaic Games of 182 BC.[41] In the same year, Aristonicus led a naval raid on Syria, attacking the island of Aradus.[38]

Ptolemy V died suddenly in September 180 BC, not yet thirty years old. The ancient historians allege that he was poisoned by his courtiers, who believed that he intended to seize their property in order to fund his new Syrian war.[42][38][2]

Regime

Ptolemaic dynastic cult

Ptolemaic Egypt had a dynastic cult, which centred on the Ptolemaia festival and the annual priest of Alexander the Great, whose full title included the names of all the Ptolemaic monarchs and appeared in official documents as part of the date formula. Probably at the Ptolemaia festival in 199 BC, Ptolemy V was proclaimed to be the Theos Epiphanes Eucharistos (Manifest, Beneficent God) and his name was added to the title of the Priest of Alexander. When he married Cleopatra I in 194–3 BC, the royal couple were deified as the Theoi Epiphaneis (Manifest Gods) and the Priest of Alexander's full title was modified accordingly.[43]

Since the death of Ptolemy V's predecessor Arsinoe II, deceased Ptolemaic queens had been honoured with a separate dynastic cult of their own, including a separate priestess who marched in religious processions in Alexandria behind the priest of Alexander the Great and whose names also appeared in dating formulae. That trend continued under Ptolemy V with the establishment of a cult for his mother in 199 BC. Unlike the canephore of Arsinoe II and the athlophore of Berenice II, Arsinoe III's priestess had no special title and served for life rather than a single year.[44][43]

With the loss of most of the Ptolemaic possessions outside Egypt in the Fifth Syrian War, Cyprus assumed a much more important role within the Ptolemaic empire and this was asserted by the establishment of a centralised religious structure on the island. The governor (strategos) of Cyprus was henceforth also the island's high priest (archiereus), responsible for maintaining a version of the dynastic cult on the island.[43]

Pharaonic ideology and Egyptian religion

Like his predecessors, Ptolemy V assumed the traditional Egyptian role of pharaoh and the concomitant support for the Egyptian priestly elite. As under the two previous rulers, the symbiotic relationship between the king and the priestly elite was affirmed and articulated by the decrees of priestly synods. Under Ptolemy V there were three of these, all of which were published on stelae in hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Greek were published throughout Egypt.[45]

The first of these decrees was the Memphis decree, passed on 27 March 196 BC, the day after Ptolemy V's coronation, in which the king is presented as the 'image of Horus, son of Isis and Osiris'. The decree's description of Ptolemy V's victory over the Lycopolis rebels and of his coronation draws heavily on traditional imagery that presented the pharaoh as a new Horus, receiving the kingship from his dead father, whom he avenges by smiting the enemies of Egypt and restoring order. In honour of his benefactions, the priests awarded him religious honours modelled on those granted by the priestly synods to his father and grandfather: they agreed to erect a statue of Ptolemy V in the shrine of every temple in Egypt and to celebrate an annual festival on his birthday.[45]

These honours were augmented in the Philensis II decree passed in September 186 BC on the suppression of Ankhmakis' revolt. The priests undertook to erect another statue of Ptolemy V in the guise of 'Lord of Victory' in the sanctuary of every temple in Egypt alongside a statue of the main deity of the temple, and to celebrate a festival in honour of Ptolemy V and Cleopatra I every year on the day of Ankhmakis' defeat.[46][45] This decree was revised in the Philensis I decree, passed in autumn 185 BC on the enthronement of an Apis bull. This decree reinstated the honours for Arsinoe Philadelphus (Arsinoe II) and the Theoi Philopatores (Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III) in the temples of Upper Egypt, which had been abolished during Ankhmakis' revolt. It also granted Cleopatra I all the various honours that had been granted to Ptolemy V in the earlier decrees.[45]

Ptolemy V's predecessors, since the time of Alexander the Great, had pursued a wide-ranging policy of temple construction, designed to ensure the support of the priestly elite. Ptolemy V was not able to do this on the same scale as his predecessors. One reason for this was the more difficult financial circumstances of Egypt during his reign. Another was the loss of large sections of the country to the rebels - at the temple of Horus at Edfu, for example, it had been planned that a large set of doors would be installed in 206 BC, but the rebellion meant that this did not actually take place until the late 180s. What construction was carried out under Ptolemy V was focussed in the northern part of the country, particularly the sanctuary of the Apis Bull and the temple of Anubis at Memphis. Hölbl interprets this work as part of an effort to build up Memphis as the centre of Egyptian religious authority, at the expense of Thebes, which had been a stronghold of the Egyptian revolt.[47]

Marriage and issue

Ptolemy V married Cleopatra I, daughter of the Seleucid king Antiochus III, in 194 BC and they had three children, who would rule Egypt in various combinations and with a great deal of conflict for most of the rest of the second century BC.[48]

| Name | Image | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ptolemy VI |  | May/June 186 BC | 145 BC | Succeeded as King under the regency of his mother in 180 BC, co-regent and spouse of Cleopatra II from 170 to 164 BC and again 163-145 BC. |

| Cleopatra II |  | 186-184 BC | 6 April 115 BC | Co-regent and wife of Ptolemy VI from 170 to 145 BC, co-regent and spouse of Ptolemy VIII from 145 to 132 BC, claimed sole rule 132-127 BC, co-regent and spouse of Ptolemy VIII again from 124 to 115 BC, co-regent with her daughter Cleopatra III and grandson Ptolemy IX from 116 to 115 BC. |

| Ptolemy VIII |  | c. 184 BC | 26 June 116 BC | Co-regent with Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II from 169 to 164 BC, expelled Ptolemy VI in 164, expelled in turn 163 BC, King of Cyrenaica from 163 to 145 BC, co-regent with Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III from 145 to 132 BC and again from 124 to 116 BC. |

Notes

- Numbering the Ptolemies is a modern convention. Older sources may give a number one higher or lower. The most reliable way of determining which Ptolemy is being referred to in any given case is by epithet (e.g. "Philopator").

- The Rosetta decree gives Ptolemy V's official birthday as 30 Mesore (which fell on 9 October in 210 BC). Since this is the date of a major Egyptian festival, some scholars have questioned whether it was his actual birthday. The same decree gives his accession date as 17 Phaophi (30 November in 210 BC) in the hieroglyphic text, but as 17 Mecheir in the demotic text (29 March in 209 BC). Ludwig Koenen has proposed that 30 Mesore was actually Ptolemy V's accession date: Koenen 1977, p. 73.

References

- Clayton (2006) p. 208.

- Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy V". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Hölbl, Günther (2013-02-01). A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. Routledge. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-135-11983-6.

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (2006). Mediterranean Anarchy, Interstate War, and the Rise of Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 23-24. ISBN 9780520246188.

- Hölbl 2001, pp. 127–133

- Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy IV". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Justin, Epitome of Pompeius Trogus 30.2; Polybius 15.25.3

- Hölbl 2001, pp. 134–136

- Polybius 15.25.11-13

- Polybius 15.20, 16.1.9, 16.10.1; Justin, Epitome of Pompeius Trogus 30.2.8; Livy Ab Urbe Condita 31.14.5; Appian Macedonica 4.1.

- Polybius 15.25.16-19

- Polybius 16.25.20-27.3

- Polybius 15.27-34

- Bevan, Chapter 8.

- Polybius 16.21-22

- Justin 30.2.8

- Hölbl 2001, pp. 136–140

- Polybius 16.39; Porphyry FGrH 260 F45-46

- Polybius 16.8-19, 22a

- Polybius 16.27.5; Livy Ab Urbe Condita 31.2.3

- Livy Ab Urbe Condita 31.43.5-7

- Livy Ab Urbe Condita 33.20.4; Porphyry FGrH 260 F46

- Polybius 18.40a; Livy Ab Urbe Condita 22.28.1; Porphyry FGrH 260 F45-46

- Hölbl 2001, pp. 155–157

- Bennett, Chris. "Horwennefer / Ankhwennefer". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Polybius 22.17.1; Rosetta Stone decree 11

- Polybius 18.55.3-6

- Polybius 18.55.7; Diodorus Bibliotheca 18.14; Plutarch Moralia 71c-d.

- British Museum. "History of the World in 100 Objects:Rosetta Stone". BBC.

- Hölbl 2001, p. 165

- Polybius 18.49-52; Livy Ab Urbe Condita 33.39-41; Appian, Syriaca 3.

- Livy Ab Urbe Condita 33.13; Cassius Dio 19.18

- Bennett, Chris. "Cleopatra I". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Polybius 22.17.3-7

- Livy Ab Urbe Condita 36.41

- Livy Ab Urbe Condita 37.3.9-11

- Polybius 21.45.8; Livy Ab Urbe Condita 38.39

- Hölbl 2001, pp. 141–143

- Polybius 22.22

- Polybius 22.3.5-9, 22.9

- IG II2 2314, line 41; S. V. Tracy & C. Habicht, Hesperia 60 (1991) 219

- Diodorus Bibliotheca 29.29; Jerome, Commentary on Daniel 11.20

- Hölbl 2001, p. 171

- Bennett, Chris. "Arsinoe III". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Hölbl 2001, pp. 165–167

- Translated text on attalus.org

- Hölbl 2001, p. 162

- Chris Bennett. "Cleopatra I". Tyndale House. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

Bibliography

- Bevan, Edwyn Robert (1927). A History of Egypt Under the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Methuen. OCLC 876137911.

- Hölbl, Günther (2001). A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. London & New York: Routledge. pp. 143–152 & 181–194. ISBN 0415201454.

- Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicles of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

External links

- Ptolemy V Epiphanes entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Greek section of Rosetta Stone and Second Philae Decree in English translation