Three-sector model

The three-sector model in economics divides economies into three sectors of activity: extraction of raw materials (primary), manufacturing (secondary), and service industries which exist to facilitate the transport, distribution and sale of goods produced in the secondary sector (tertiary).[1] The model was developed by Allan Fisher,[2][3][4] Colin Clark,[5] and Jean Fourastié[6] in the first half of the 20th century, and is a representation of an industrial economy. It has been criticised as inappropriate as a representation of the economy in the 21st century.[7]

| Economic sectors |

|---|

| Three-sector model |

|

| Additional sectors |

|

| Theorists |

| Sectors by ownership |

| Grey market |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

Major types

|

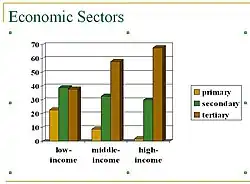

According to the three-sector model, the main focus of an economy's activity shifts from the primary, through the secondary and finally to the tertiary sector. Countries with a low per capita income are in an early state of development; the main part of their national income is achieved through production in the primary sector. Countries in a more advanced state of development, with a medium national income, generate their income mostly in the secondary sector. In highly developed countries with a high income, the tertiary sector dominates the total output of the economy.

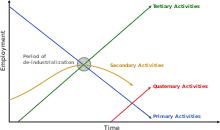

The rise of the post-industrial economy in which an increasing proportion of economic activity is not directly related to physical goods has led some economists to expand the model by adding a fourth quaternary or fifth quinary sectors, while others have ceased to use the model.

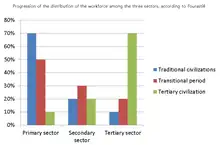

Structural transformation according to Fourastié

Fourastié saw the process as essentially positive, and in The Great Hope of the Twentieth Century he wrote of the increase in quality of life, social security, blossoming of education and culture, higher level of qualifications, humanisation of work, and avoidance of unemployment.[6] The distribution of the workforce among the three sectors progresses through different stages as follows, according to Fourastié:

First phase: Traditional civilizations

Workforce quotas:

- Primary sector: 64.5%

- Secondary sector: 20%

- Tertiary sector: 15.5%

This phase represents a society which is scientifically not yet very developed, with a negligible use of machinery. The state of development corresponds to that of European countries in the early Middle Ages, or that of a modern-day developing country.

Second phase: Transitional period

Workforce quotas:

- Primary sector: 40%

- Secondary sector: 40%

- Tertiary sector: 20%

More machinery is deployed in the primary sector, which reduces the number of workers needed to produce a given output of food and raw materials. Since the food requirements of a given population do not change much, employment in agriculture declines as a proportion of the population.

As a result, the demand for machinery production in the secondary sector increases and workers move from agriculture to manufacturing. The transitional way or phase begins with an event which can be identified with the industrialisation: far-reaching mechanisation (and therefore automation) of manufacture, such as the use of conveyor belts. The tertiary sector begins to develop, as do the financial sector and the power of the state.

Third phase: Tertiary civilization

Workforce quotas:

- Primary sector: 10%

- Secondary sector: 20%

- Tertiary sector: 70%

The primary and secondary sectors are increasingly dominated by automation, and the demand for workforce numbers falls in these sectors. It is replaced by the growing demands of the tertiary sector, where productivity growth is slower.[8]

Criticism of Fourastié's model

Various empirical studies seemingly confirm the three-sector hypothesis, but employment in the primary sector fell far more than Fourastié predicted. Germany's Federal Statistical Office study shows the following employment proportions for 2014: primary sector at 1.5%, secondary sector at 24.6%, and tertiary sector at 73.9%.[9]Furthermore, four incorrect predictions can be found in his book on the subject:[10]

Fourastié predicted that the transition from the secondary to the tertiary sector would eliminate the problem of unemployment as, in his opinion, this sector could not be rationalized. When he conceived of the theory in the 1930s, however, he did not foresee the enormous technological progress made in the service sector, such as invention of the modern computer bringing with it the digital revolution. Fourastié's false prognosis is that there will be no country in the highly developed third phase which also has a significant secondary sector. The best example to counter this is Germany: in German economy, the secondary sector has sharply declined since the 1950s, but not quite to the level that Fourastié predicted due to Germany's high exports. Another Fourastié's false prediction states that the tertiary sector would always place high demands on employees in terms of education, which is not the case, since the service occupations also include cleaning services, shoeshining, parcel delivery service etc. The high level of income equality predicted by Fourastié also did not take place; in fact, the opposite development has happened: the inequality of income distribution has been increasing in most OECD countries. Fourastié described the tertiary sector - which is usually seen as equivalent with the service sector - as a production sector enjoying little to no technical progress and thus offering at best a slight increase in labor productivity. Confinement of the service sector within the tertiary sector today is only tenable in few areas. Instead, addition of the fourth "information sector" can be seen, leading towards the development of a knowledge society.

Extensions to the three-sector model

Further development has led to the service or post-industrial society. Today the service sector has grown to such an enormous size that it is sometimes further divided into an information-based quaternary sector, and even a quinary sector based on human services.

Quaternary sector

The quaternary sector, sometimes referred to as the research and development sector, consists mainly of businesses providing information services, intellectual activities and knowledge based activities aimed at future growth and development.

Activities include, and are mainly composed of: scientific research, ICT/computing, education, consulting, information management and financial planning.

Contrary to what might be inferred from the naming convention, the quaternary sector does not add value to the outputs of the tertiary sector, but provides services directly with limited reliance on purchased inputs. The output of the quaternary sector is difficult to measure. The volume of information produced has grown rapidly, in line with Moore's Law.[11]

Quinary sector

Definitions of the quinary sector vary significantly. Some define it as merely non-profit work such as for charities and NGOs.

Others define it as the sector that focuses on human services and control, such as government and some charities, as well as creation or non-routine use of information and new technologies, linking slightly with the quaternary sector.[12]

Sometimes referred to as ‘gold collar’ professions,[13] they include special and highly paid skills of senior business executives, government officials, research scientists, financial and legal consultants, etc. The highest level of decision makers or policy makers perform quinary activities.[12]

Value added, national accounts and the three sector model

The 3 sector model is closely related to the development of national accounts, notably by Colin Clark. The concept of value added is central to national accounting. Value added in the secondary sector of the economy (manufacturing) is equal to the difference between the (wholesale) value of goods produced and the cost of raw materials supplied by the primary sector. Similarly, the value added by the tertiary sector is equal to the difference between the retail price paid by consumers and the wholesale price paid to manufacturers.

The concept of value added is less useful in relation to the quaternary and quinary sectors.

See also

References

- Kjeldsen-Kragh, Søren (2007). The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development: The Lessons of History. Copenhagen Business School Press DK. p. 73. ISBN 978-87-630-0194-6.

- Fisher, Allan G. B. (1935). The Clash of Progress and Security. London: Macmillan. Archived from the original on 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- Fisher, Allan G. B. (1939). "Production, primary, secondary and tertiary". Economic Record. 15 (1): 24–38. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4932.1939.tb01015.x. ISSN 1475-4932.

- Fisher, Allan G. B. (1946). Economic Progress And Social Security. London: Macmillan. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

- Colin Clark (1940). The Conditions of Economic Progress. London: Macmillan. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- Fourastié, Jean (1949). Le grand espoir du XXe siècle: Progrès technique, progrès économique, progrès social (in French). Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

- Schafran, Alex; McDonald, Conor; López-Morales, Ernesto; Akyelken, Nihan; Acuto, Michele (2018). "Replacing the services sector and three-sector theory: urbanization and control as economic sectors". Regional Studies. 52 (12): 1708–1719. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1464136. S2CID 158415916. Archived from the original on 2022-08-10. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- Baumol, William (1967). "Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: The anatomy of urban crisis". American Economic Review. 57 (47): 415–26. JSTOR 1812111. Archived from the original on 2020-12-27. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- "Gesamtwirtschaft & Umwelt - Arbeitsmarkt - Arbeitsmarkt - Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis)" [Overall economy & environment - Labor market - Federal Statistical Office report(Destatis)] (in German). www.destatis.de. Archived from the original on 2017-03-13. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- Jean Fourastié: Le Grand Espoir du XXe siècle. Progrès technique, progrès économique, progrès social. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1949 (The 20th century's Great Hope. Technological progress, economic progress, social progress.

- Quiggin, John (2014). "National accounting and the digital economy" (PDF). Economic Analysis and Policy. 44 (2): 136–142. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2014.05.008.

- Kellerman, Aharon (1985-05-01). "The evolution of service economies: A geographical perspective 1". The Professional Geographer. 37 (2): 133–143. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.1985.00133.x. ISSN 0033-0124.

- "Sectors of Economy: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary, Quaternary and Quinary". 2014-10-05. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

Further reading

- Bernhard Schäfers: Sozialstruktur und sozialer Wandel in Deutschland. ("Social Structure and Social Change in Germany") Lucius und Lucius, Stuttgart 7th edition 2002

- Clark, Colin (1940) Conditions of Economic Progress

- Fisher, Allan GB. Production, primary, secondary and tertiary. Economic Record 15.1 (1939): 24-38

- Rainer Geißler: Entwicklung zur Dienstleistungsgesellschaft. In: Informationen zur politischen Bildung. Nr. 269: Sozialer Wandel in Deutschland, 2000, p. 19f.

- Hans Joachim Pohl: Kritik der Drei-Sektoren-Theorie. ("Criticism of the Three Sector Theory") In: Mitteilungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung. Issue 4/Year 03/1970, p. 313-325

- Stefan Nährlich: Dritter Sektor: "Organisationen zwischen Markt und Staat." ("Third Sector: Organizations Between Market and State"). From "Theorie der Bürgergesellschaft" des Rundbriefes Aktive Bürgerschaft ("Theory of the Civil Society" of the newsletter "Active Civil Society") 4/2003

- Uwe Staroske: Die Drei-Sektoren-Hypothese: Darstellung und kritische Würdigung aus heutiger Sicht ("The Three-Sector-Hypothesis: Presentation and Critical Appraisal from a Contemporary View"). Roderer Verlag, Regensburg 1995