Cape Verde

Cape Verde (/ˈvɜːrd(i)/ ⓘ, VURD or VUR-dee) or Cabo Verde (/ˌkɑːboʊ ˈvɜːrdeɪ/ ⓘ, /ˌkæb-/ KA(H)B-oh VUR-day; Portuguese: [ˈkaβu ˈveɾðɨ]), officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an archipelago and island country in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about 4,033 square kilometres (1,557 sq mi).[9] These islands lie between 600 and 850 kilometres (320 and 460 nautical miles) west of Cap-Vert, the westernmost point of continental Africa. The Cape Verde islands form part of the Macaronesia ecoregion, along with the Azores, the Canary Islands, Madeira, and the Savage Isles.

Republic of Cabo Verde | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

| Anthem: Cântico da Liberdade (Portuguese) (English: "Chant of Freedom") | |

.svg.png.webp)  | |

| Capital and largest city | Praia 14°54′59″N 23°30′34″W |

| Official languages | Portuguese[1] |

| Recognised national languages | Cape Verdean Creole[1] |

| Religion (2018) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Cape Verdean or Cabo Verdean[3] |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[4] |

| José Maria Neves | |

| Ulisses Correia e Silva | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from Portugal | |

• Granted | 5 July 1975 |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,033 km2 (1,557 sq mi) (166th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2021 census | 561,901[5] (172nd) |

• Density | 123.7/km2 (320.4/sq mi) (89th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $4.413 billion |

• Per capita | $7,740[6] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $1.997 billion |

• Per capita | $3,502[6] |

| Gini (2015) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 128th |

| Currency | Cape Verdean escudo (CVE) |

| Time zone | UTC–1 (CVT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +238 |

| ISO 3166 code | CV |

| Internet TLD | .cv |

The Cape Verde archipelago was uninhabited until the 15th century, when Portuguese explorers discovered and colonized the islands, thus establishing the first European settlement in the tropics. Because the Cape Verde islands were conveniently located to play a role in the Atlantic slave trade, Cape Verde became economically prosperous during the 16th and 17th centuries, attracting merchants, privateers, and pirates. It declined economically in the 19th century after the suppression of the Atlantic slave trade, and many of its inhabitants emigrated during that period. However, Cape Verde gradually recovered economically by becoming an important commercial center and useful stopover point along major shipping routes. Cape Verde became independent in 1975.

Since the early 1990s, Cape Verde has been a stable representative democracy and has remained one of the most developed and democratic countries in Africa. Lacking natural resources, its developing economy is mostly service-oriented, with a growing focus on tourism and foreign investment. Its population of around 483,628 (as of the 2021 Census) is mostly of African and a minor European heritage, and predominantly Roman Catholic, reflecting the legacy of Portuguese rule. A sizeable Cape Verdean diaspora community exists across the world, especially in the United States and Portugal, considerably outnumbering the inhabitants on the islands. Cape Verde is a member state of the African Union.

Cape Verde's official language is Portuguese.[10] It is the language of instruction and government. It is also used in newspapers, television, and radio. The recognized national language is Cape Verdean Creole, which is spoken by the vast majority of the population.

As of the 2021 census the most populated islands were Santiago, where the capital Praia is located (269,370), São Vicente (74,016), Santo Antão (36,632), Fogo (33,519) and Sal (33,347). The largest cities are Praia (137,868), Mindelo (69,013), Espargos (24,500) and Assomada (21,297).[11]

Etymology

The country is named after the Cap-Vert peninsula, on the Senegalese coast.[12] The name Cap-Vert, in turn, comes from the Portuguese language Cabo Verde ('green cape'), the name that Portuguese explorers gave the cape in 1444, a few years before they came across the islands.

On 24 October 2013, the country's delegation to the United Nations informed it that other countries should no longer use Cape Verde or any other translations of Cabo Verde as part of its official name: all countries should use Republic of Cabo Verde as the country's official name.[9][13] Speakers of English have used the name Cape Verde for the archipelago and, since independence in 1975, for the country. In 2013, the Cape Verdean government determined that it would thenceforth use the Portuguese name Cabo Verde for official purposes, including at the United Nations, even when speaking or writing in English.

History

The archipelago of modern-day Cape Verde was formed approximately 40–50 million years ago during the Eocene era.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Cape Verde Islands were uninhabited.[14][15][16] They were discovered by Genoese and Portuguese navigators around 1456. According to Portuguese official records,[17] the first discoveries were made by Genoa-born António de Noli, who was afterwards appointed governor of Cape Verde by the Portuguese king Afonso V. Other navigators mentioned as contributing to discoveries on the Cape Verde archipelago are Diogo Dias, Diogo Afonso, Venetian Alvise Cadamosto, and Diogo Gomes (who had accompanied António de Noli on his voyage of discovery, and who claimed to have been the first to land on the Cape Verdean island of Santiago, and the first to name that island).

In 1462, Portuguese settlers arrived at Santiago and founded a settlement they called Ribeira Grande. Today it is called Cidade Velha ("Old City"), to distinguish it from a town of the same name on a different Cape Verdean island (Ribeira Grande on the island of Santo Antão). The original Ribeira Grande was the first permanent European settlement in the tropics.[18]

In the 16th century, the archipelago prospered from the Atlantic slave trade.[18] Pirates occasionally attacked the Portuguese settlements. Francis Drake, an English privateer, twice sacked the (then) capital Ribeira Grande in 1585 when it was a part of the Iberian Union.[18] After a French attack in 1712, the town declined in importance relative to nearby Praia, which became the capital in 1770.[18]

The decline in the slave trade in the 19th century resulted in an economic crisis. Cape Verde's early prosperity slowly vanished. However, the islands' position astride mid-Atlantic shipping lanes made Cape Verde an ideal location for re-supplying ships. Because of its excellent harbour, the city of Mindelo, located on the island of São Vicente, became an important commercial centre during the 19th century.[18] Diplomat Edmund Roberts visited Cape Verde in 1832.[19] Cape Verde was the first stop of Charles Darwin's voyage with HMS Beagle in 1832.[20]

With few natural resources and inadequate sustainable investment from the Portuguese, the citizens grew increasingly discontented with the colonial masters, who refused to provide the local authorities with more autonomy. In 1951, Portugal changed Cape Verde's status from a colony to an overseas province in an attempt to blunt growing nationalism.[18]

In 1956, Amílcar Cabral and a group of fellow Cape Verdeans and Guineans organized (in Portuguese Guinea) the clandestine African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC).[18] It demanded improvement in economic, social and political conditions in Cape Verde and Portuguese Guinea and formed the basis of the two nations' independence movement. Moving its headquarters to Conakry, Guinea in 1960, the PAIGC began an armed rebellion against Portugal in 1961. Acts of sabotage eventually grew into a war in Portuguese Guinea that pitted 10,000 Soviet Bloc-supported PAIGC soldiers against 35,000 Portuguese and African troops.[18]

By 1972, the PAIGC controlled much of Portuguese Guinea despite the presence of the Portuguese troops, but the organization did not attempt to disrupt Portuguese control in Cape Verde. Portuguese Guinea declared independence in 1973 and was granted de jure independence in 1974. A budding independence movement – originally led by Amílcar Cabral, assassinated in 1973 – passed on to his half-brother Luís Cabral and culminated in independence for the archipelago in 1975.

Independence (1975)

Following the April 1974 revolution in Portugal, the PAIGC became an active political movement in Cape Verde. In December 1974, the PAIGC and Portugal signed an agreement providing for a transitional government composed of Portuguese and Cape Verdeans. On 30 June 1975, Cape Verdeans elected a National Assembly which received the instruments of independence from Portugal on 5 July 1975.[18] In the late 1970s and 1980s, most African countries prohibited South African Airways from overflights but Cape Verde allowed them and became a centre of activity for the airline's flights to Europe and the United States.

Immediately following the November 1980 coup in Guinea-Bissau, relations between Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau became strained. Cape Verde abandoned its hope for unity with Guinea-Bissau and formed the African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (PAICV). Problems have since been resolved and relations between the countries are good. The PAICV and its predecessor established a one-party system and ruled Cape Verde from independence until 1990.[18]

Responding to growing pressure for pluralistic democracy, the PAICV called an emergency congress in February 1990 to discuss proposed constitutional changes to end one-party rule. Opposition groups came together to form the Movement for Democracy (MpD) in Praia in April 1990. Together, they campaigned for the right to contest the presidential election scheduled for December 1990.

The one-party state was abolished on 28 September 1990, and the first multi-party elections were held in January 1991. The MpD won a majority of the seats in the National Assembly, and MpD presidential candidate António Mascarenhas Monteiro defeated the PAICV's candidate with 73.5% of the votes. Legislative elections in December 1995 increased the MpD majority in the National Assembly. The party won 50 of the National Assembly's 72 seats.

A February 1996 presidential election returned President Monteiro to office. Legislative elections in January 2001 returned power to the PAICV, with the PAICV holding 40 of the National Assembly seats, MpD 30, and Party for Democratic Convergence (PCD) and Labour and Solidarity Party (PTS) 1 each. In February 2001, the PAICV-supported presidential candidate Pedro Pires defeated former MpD leader Carlos Veiga by only 13 votes.[18] [21] President Pedro Pires was narrowly re-elected in 2006 elections.[22]

President Jorge Carlos Fonseca led the country since 2011 Cape Verde presidential election and he was re-elected in the 2016 election. He was supported by the Movement for Democracy Party.[23] MpD also won in the 2016 parliamentary elections, taking back parliamentary majority after 15 year-rule of African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (PAICV).[24] In April 2021, the ruling center-right Movement for Democracy (MpD) of Prime Minister Ulisses Correia e Silva won the parliamentary election.[25]

On 26 August 2021, Cape Verde became the 150th country to ratify the 2005 Convention and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions.[26]

In October 2021, opposition candidate and former prime minister, Jose Maria Neves of PAICV, won Cape Verde's presidential election.[27] On 9 November 2021, Jose Maria Neves was sworn in as the new President of Cape Verde.[28]

Government and politics

Cape Verde is a stable semi-presidential representative democratic republic.[4][29] In 2020 it was the most democratic nation in Africa, ranking 2023 as 45th in the world, according to the electoral democracy score of the V-Dem Democracy indices.[30]

The constitution – adopted in 1980 and revised in 1992, 1995 and 1999 – defines the basic principles of its government. The president is the head of state and is elected by popular vote for a five-year term.[18]

The prime minister is the head of government and proposes other ministers and secretaries of state. The prime minister is nominated by the National Assembly and appointed by the president. Members of the National Assembly are elected by popular vote for five-year terms. In 2016, three parties held seats in the National Assembly – MpD (36), PAICV (25), and the Cape Verdean Independent Democratic Union (UCID) (3).[31]

The two main political parties are PAICV and MpD.[31]

Movement for Democracy (MpD) ousted the ruling African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (PAICV) for the first time in 15 years in the 2016 parliamentary election, at which time its leader, Ulisses Correia e Silva, became prime minister. Jorge Carlos Almeida Fonseca was elected president in August 2011 and re-elected in October 2016. He is also supported by the MpD.[32]

In November 2021, Cape Verde opened its first embassy in Nigeria. [33]

International recognition

Cape Verde is often praised as an example among African nations for its stability and developmental growth despite its lack of natural resources. In 2013 then United States President Barack Obama said Cape Verde is "a real success story".[34] Among other achievements, it has been recognized with the following assessments:

| Index | Score | PALOP rank | CPLP rank | African rank | World rank | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Development Index | 0.654 | 1 (top 17%) | 3 (top 38%) | 10 (top 19%)[A] | 125 (top 62%) | 2017[35] |

| Ibrahim Index of African Governance | 71.1 | 1 (top 17%) | — | 3 (top 6%) | — | 2018[36] |

| Freedom of the Press | 27 (Free) | 1 (top 17%) | 2 (top 25%) | 1 (top 2%) | 48 (top 24%) | 2014 |

| Freedom in the World | 1/1[B] | 1 (top 17%) | 1 (top 13%)[C] | 1 (top 2%)[D] | 1 (top 1%)[E] | 2016 |

| Press Freedom Index | 18.02 | 1 (top 17%) | 2 (top 25%) | 3 (top 6%) | 27 (top 14%) | 2017 |

| Democracy Index | 7.88 (Flawed democracy) | 1 (top 17%) | 1 (top 13%) | 2 (top 4%) | 26 (top 13%) | 2018 |

| Corruption Perceptions Index | 59 | 1 (top 17%) | 2 (top 25%) | 2 (top 4%) | 38 (top 19%) | 2016 |

| Index of Economic Freedom[37] | 66.5 | 1 (top 17%) | 1 (top 13%) | 3 (top 6%) | 57 (top 28%) | 2016 |

| e-Government Readiness Index | 0.3551 | 1 (top 17%) | 3 (top 38%) | 14 (top 26%) | 127 (top 63%) | 2014 |

| Failed States Index | 74.1 | 1 (top 17%) | 3 (top 38%) | 8 (top 15%) | 93 (top 46%)[F] | 2014 |

| Networked Readiness Index | 3.8 | 1 (top 17%) | 3 (top 38%) | 7 (top 13%) | 87 (top 43%) | 2015[38] |

- A See List of countries by Human Development Index § Africa

- B 1/1 is the highest possible rating.

- With the maximum score, Cape Verde shares first place with Portugal.

- D Cape Verde was the only African country to reach the maximum rating.

- With the maximum score, Cape Verde shares first place with 48 other countries.

- F The rank on this list is expressed in reverse order. To be comparable with the other rankings on this table, the actual rank of 88 was inverted, by subtracting it from the number of countries on the list, currently 177.

Foreign relations

Cape Verde follows a policy of nonalignment and seeks cooperative relations with all friendly states.[18] Angola, Brazil, China, Libya, Cuba, France, Guinea-Bissau, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, São Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Russia, Luxembourg, and the United States maintain embassies in Praia.[18] Cape Verde maintains a vigorously active foreign policy, especially in Africa.[18]

Cape Verde is a founding member state of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth, an international organization and political association of Lusophone nations across four continents, where Portuguese is an official language.

Cape Verde has bilateral relations with some Lusophone nations and holds membership in a number of international organizations.[18] It also participates in most international conferences on economic and political issues.[18] Since 2007, Cape Verde has a special partnership status[39] with the EU, under the Cotonou Agreement, and might apply for special membership, in particular because the Cape Verdean escudo, the country's currency, is indexed to the euro.[40] In 2011 Cape Verde ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[41] In 2017 Cape Verde signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[42]

Judiciary

The judicial system consists of a Supreme Court of Justice – whose members are appointed by the president, the National Assembly, and the Board of the Judiciary – and regional courts. Separate courts hear civil, constitutional, and criminal cases. Appeals are to the Supreme Court.[18]

Military

The military of Cape Verde consists of the National Guard and the Coast Guard; 0.7% of the country's GDP was spent on the military in 2005.

Having fought their only battles in the war for independence against Portugal between 1974 and 1975, the efforts of the Cape Verdean armed forces have turned to combating international drug trafficking. In 2007, together with the Cape Verdean Police, they carried out Operation Flying Launch (Operacão Lancha Voadora), a successful operation to put an end to a drug trafficking group which smuggled cocaine from Colombia to the Netherlands and Germany using the country as a reorder point. The operation took more than three years, being a secret operation during the first two years, and ended in 2010. In 2016, Cape Verdean Armed Forces were involved in the Monte Tchota massacre, a green-on-green incident that resulted in 11 deaths.[43]

Geography

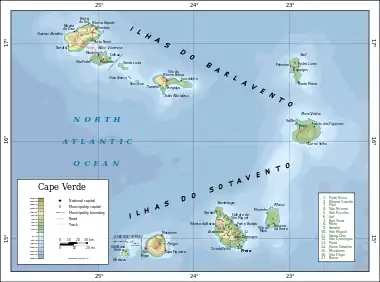

The Cape Verde archipelago is in the Atlantic Ocean, approximately 570 kilometres (350 mi) off the western coast of the African continent, near Senegal, The Gambia, and Mauritania as well as part of the Macaronesia ecoregion. It lies between latitudes 14° and 18°N, and longitudes 22° and 26°W.

The country is a horseshoe-shaped cluster of ten islands (nine inhabited) and eight islets,[44] that constitute an area of 4033 km2 (1557 sq mi).[44]

The islands are spatially divided into two groups:

- The Barlavento Islands (windward islands): Santo Antão, São Vicente, Santa Luzia, São Nicolau, Sal, Boa Vista;[44] and

- The Sotavento Islands (leeward): Maio, Santiago, Fogo, Brava.[44]

The largest island, both in size and population, is Santiago, which hosts the nation's capital, Praia, the principal urban agglomeration in the archipelago.[44]

Three of the Cape Verde islands, Sal, Boa Vista, and Maio, are fairly flat, sandy, and dry; the others are generally rockier with more vegetation.

Physical geography and geology

.jpg.webp)

Geologically, the islands, covering a combined area of slightly over 4,033 square kilometres (1,557 square miles), are principally composed of igneous rocks, with volcanic structures and pyroclastic debris comprising the majority of the archipelago's total volume. The volcanic and plutonic rocks are distinctly basic; the archipelago is a soda-alkaline petrographic province, with a petrologic succession similar to that found in other Macaronesian islands.

Magnetic anomalies identified in the vicinity of the archipelago indicate that the structures forming the islands date back 125–150 million years: the islands themselves date from 8 million (in the west) to 20 million years (in the east).[45] The oldest exposed rocks occurred on Maio and the northern peninsula of Santiago and are 128–131 million-year-old pillow lavas. The first stage of volcanism in the islands began in the early Miocene, and reached its peak at the end of this period when the islands reached their maximum sizes. Historical volcanism (within human settlement) has been restricted to the island of Fogo.[46]

The islands lie on a bathymetric swell known as the Cape Verde Rise.[47] The Rise is one of the largest protuberances in the world's oceans, rising 2.2 kilometres (1.4 miles) in a semi-circular region of 1200 km2 (460 sq mi), associated with a rise of the geoid.[45]

Pico do Fogo, the largest active volcano in the region, erupted in 2014. It has an eight-kilometre-diameter (five-mile) caldera, the rim of which is at an elevation of 1,600 metres (5,249 feet) and an interior cone that rises to 2,829 metres (9,281 feet) above sea level. The caldera resulted from subsidence, following the partial evacuation (eruption) of the magma chamber, along a cylindrical column from within the magma chamber (at a depth of 8 kilometres (5 miles)).

Extensive salt flats are found on Sal and Maio.[44] On Santiago, Santo Antão, and São Nicolau, arid slopes give way in places to sugarcane fields or banana plantations spread along the base of towering mountains.[44] Ocean cliffs have been formed by catastrophic debris landslides.[48]

Climate

Cape Verde's climate is milder than that of the African mainland because the surrounding sea moderates temperatures on the islands and cold Atlantic currents produce an arid atmosphere around the archipelago. Conversely, the islands do not receive the upwelling (cold streams) that affect the West African coast, so the air temperature is cooler than in Senegal, but the sea is warmer. Due to the relief of some islands, such as Santiago with its steep mountains, the islands can have orographically induced precipitation, allowing rich woods and luxuriant vegetation to grow where the humid air condenses soaking the plants, rocks, soil, logs, moss, etc. On the higher islands and somewhat wetter islands, exclusively in mountainous areas, like Santo Antão island, the climate is suitable for the development of dry monsoon forests, and laurel forests.[44] Average temperatures range from 22 °C (72 °F) in February to 27 °C (80.6 °F) in September.[49] Cape Verde is part of the Sahelian arid belt, with nothing like the rainfall levels of nearby West Africa.[44] It rains irregularly between August and October, with frequent brief heavy downpours.[44] A desert is usually defined as terrain that receives less than 250 mm (9.8 in) of annual rainfall. Sal's total of 145 mm (5.7 in) confirms this classification. Most of the year's rain falls in September.[49]

Sal, Boa Vista, and Maio have a flat landscape and arid climate, whilst the other islands are generally rockier and have more vegetation. Because of the infrequent occurrence of rainfall, where not mountainous, the landscape is so arid that less than two percent of it is arable.[50] The archipelago can be divided into four broad ecological zones – arid, semiarid, subhumid and humid, according to altitude and average annual rainfall ranging from less than 100 millimetres (3.9 inches) in the arid areas of the coast as in the Deserto de Viana (67 millimetres (2.6 inches) in Sal Rei) to more than 1,000 millimetres (39 inches) in the humid mountain. Most rainfall precipitation is due to condensation of the ocean mist.

.jpg.webp)

In some islands, like Santiago, the wetter climate of the interior and the eastern coast contrasts with the drier one on the south/southwest coast. Praia, on the southeast coast, is the largest city on the island and the largest city and capital of the country.

While most of Cape Verde receives little precipitation throughout the year, the northeastern slopes of high mountains see significant rainfall due to orographic lift, especially in areas far from the sea. In some such areas this precipitation is sufficient to support a rainforest habitat, albeit one significantly affected by the islands' human presence. These umbria areas are identified as cool and moist. Cape Verde lies in the Cape Verde Islands dry forests ecoregion.[51]

Western Hemisphere-bound hurricanes often have their early beginnings near the Cape Verde Islands. These are referred to as Cape Verde-type hurricanes. These hurricanes can become very intense as they cross warm Atlantic waters away from Cape Verde. The average hurricane season has about two Cape Verde-type hurricanes, which are usually the largest and most intense storms of the season because they often have plenty of warm open ocean over which to develop before encountering land. The five largest Atlantic tropical cyclones on record have been Cape Verde-type hurricanes. Most of the longest-lived tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin are Cape Verde hurricanes.

As of 2015, the islands themselves have only been struck by hurricanes twice in recorded history (since 1851): once in 1892, and again in 2015 by Hurricane Fred, the easternmost hurricane ever to form in the Atlantic.

| Climate data for Cape Verde: São Vicente, Sal and Santiago, 1981–2010 normals, 1931–1960 extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

34.2 (93.6) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.6 (92.5) |

38.0 (100.4) |

34.8 (94.6) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.0 (91.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

38.0 (100.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24.9 (76.8) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.1 (71.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 19.4 (66.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.0 (60.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 4.9 (0.19) |

1.5 (0.06) |

0.7 (0.03) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.0 (0.0) |

3.9 (0.15) |

30.2 (1.19) |

41.7 (1.64) |

18.8 (0.74) |

3.7 (0.15) |

3.1 (0.12) |

109.2 (4.3) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.9 | 67.3 | 66.9 | 67.8 | 69.5 | 72.3 | 73.8 | 75.3 | 76.0 | 73.5 | 70.7 | 69.5 | 70.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 213.4 | 184.9 | 197.1 | 199.0 | 195.4 | 175.1 | 165.4 | 160.7 | 165.1 | 185.3 | 186.2 | 202.9 | 2,230.5 |

| Source 1: Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia e Geofísica[49] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes)[52][53][54] | |||||||||||||

Climate Change

According to the president of Nauru, in 2011 Cape Verde was ranked the eighth most endangered nation due to flooding from climate change.[55] In 2023 UN Secretary-General António Guterres arrived in Cabo Verde to raise concerns about climate change. He said that the country is on the frontlines of the existential crisis generated by climate disruptions and that world leaders need to take action to address the climate crisis.[56] Cabo Verde is a leader in renewable energy in sub-Saharan Africa. Currently, 20% of its energy comes from renewable sources, and the goal is to increase that to 50% by 2030.[57] In 2023, Portugal signed an agreement to forgive €140 million of Cape Verde's debt in exchange for the country investing in environmental projects. This agreement is one of the first debt-for-nature swap in Africa.[58]

Biodiversity

Cape Verde's isolation has resulted in the islands having several endemic species, particularly birds and reptiles, many of which are endangered by human development. Endemic birds include Alexander's swift (Apus alexandri), Bourne's heron (Ardea purpurea bournei), the Raso lark (Alauda razae), the Cape Verde warbler (Acrocephalus brevipennis), and the Iago sparrow (Passer iagoensis).[59] The islands are also an important breeding area for seabirds including the Cape Verde shearwater. Reptiles include the Cape Verde giant gecko (Tarentola gigas).

Administrative divisions

Cape Verde is divided into 22 municipalities (concelhos) and subdivided into 32 parishes (freguesias), based on the religious parishes that existed during the colonial period:

| Island | Municipality | Census 2010[60] | Census 2021[61] | Parish |

| Santo Antão | Ribeira Grande | 18,890 | 15,022 | Nossa Senhora do Rosário |

| Nossa Senhora do Livramento | ||||

| Santo Crucifixo | ||||

| São Pedro Apóstolo | ||||

| Paúl | 6,997 | 5,696 | Santo António das Pombas | |

| Porto Novo | 18,028 | 15,014 | São João Baptista | |

| Santo André | ||||

| São Vicente | São Vicente | 76,107 | 74,016 | Nossa Senhora da Luz |

| Santa Luzia | ||||

| São Nicolau | Ribeira Brava | 7,580 | 6,978 | Nossa Senhora da Lapa |

| Nossa Senhora do Rosário | ||||

| Tarrafal de São Nicolau | 5,237 | 5,261 | São Francisco | |

| Sal | Sal | 25,765 | 33,347 | Nossa Senhora das Dores |

| Boa Vista | Boa Vista | 9,162 | 12,613 | Santa Isabel |

| São João Baptista |

| Island | Municipality | Census 2010[60] | Census 2021[61] | Parish |

| Maio | Maio | 6,952 | 6,298 | Nossa Senhora da Luz |

| Santiago | Praia | 131,602 | 142,009 | Nossa Senhora da Graça |

| São Domingos | 13,808 | 13,958 | Nossa Senhora da Luz | |

| São Nicolau Tolentino | ||||

| Santa Catarina | 43,297 | 37,472 | Santa Catarina | |

| São Salvador do Mundo | 8,677 | 7,452 | São Salvador do Mundo | |

| Santa Cruz | 26,609 | 25,004 | Santiago Maior | |

| São Lourenço dos Órgãos | 7,388 | 6,317 | São Lourenço dos Órgãos | |

| Ribeira Grande de Santiago | 8,325 | 7,632 | Santíssimo Nome de Jesus | |

| São João Baptista | ||||

| São Miguel | 15,648 | 12,906 | São Miguel Arcanjo | |

| Tarrafal | 18,565 | 16,620 | Santo Amaro Abade | |

| Fogo | São Filipe | 22,228 | 20,732 | São Lourenço |

| Nossa Senhora da Conceição | ||||

| Santa Catarina do Fogo | 5,299 | 4,725 | Santa Catarina do Fogo | |

| Mosteiros | 9,524 | 8,062 | Nossa Senhora da Ajuda | |

| Brava | Brava | 5,995 | 5,594 | São João Baptista |

| Nossa Senhora do Monte |

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Cape Verde's notable economic growth and improvement in living conditions despite a lack of natural resources have garnered international recognition, with other countries and international organizations often providing development aid. Since 2007, the UN has classified it as a developing nation rather than a least developed country.

Cape Verde has few natural resources. Only five of the ten main islands (Santiago, Santo Antão, São Nicolau, Fogo, and Brava) normally support significant agricultural production,[62] and over 90% of all food consumed in Cape Verde is imported. Mineral resources include salt, pozzolana (a volcanic rock used in cement production), and limestone.[18] Its small number of wineries making Portuguese-style wines have traditionally focused on the domestic market, but have recently met with some international acclaim. Several wine tours of Cape Verde's various microclimates began to be offered in spring 2010.

The economy of Cape Verde is service-oriented, with commerce, transport, and public services accounting for more than 70% of GDP. Although nearly 35% of the population lives in rural areas, agriculture and fishing contribute only about 9% of GDP. Light manufacturing accounts for most of the remainder. Fish and shellfish are plentiful, and small quantities are exported. Cape Verde has cold storage and freezing facilities and fish processing plants in Mindelo, Praia, and on Sal. Expatriate Cape Verdeans contribute an amount estimated at 20% of GDP to the domestic economy through remittances.[18] Despite having few natural resources and being semi-desert, the country boasts the highest living standards in the region and has attracted thousands of immigrants of different nationalities.

Since 1991, the government has pursued market-oriented economic policies, including an open welcome to foreign investors and a far-reaching privatization programme. It established as top development priorities the promotion of a market economy and the private sector; the development of tourism, light manufacturing industries, and fisheries; and the development of transport, communications, and energy facilities. From 1994 to 2000 about $407 million in foreign investments were made or planned, of which 58% were in tourism,[63] 17% in industry, 4% in infrastructure, and 21% in fisheries and services.[18]

In 2011, on four islands a wind farm was built that supplies about 30% of the electricity of the country.[64] As host to the ECOWAS Regional Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency, inaugurated in 2010, Cape Verde plans to lead by example by becoming entirely reliant on renewable energy sources by 2025.[65] This policy is consistent with the plethora of documents adopted in 2015 paving the way to more sustainable development, including Cape Verde's Transformational Agenda to 2030, its National Renewable Energy Plan and its Low Carbon and Climate-resilient Development Strategy. Two years later, these were followed by a Strategic Plan for Sustainable Development, 2017–2021.[65]

Between 2000 and 2009, real GDP increased on average by over seven percent a year, well above the average for Sub-Saharan countries and faster than most small island economies in the region. Strong economic performance was bolstered by one of the fastest growing tourism industries in the world, as well as by substantial capital inflows that allowed Cape Verde to build up national currency reserves to the current 3.5 months of imports. Unemployment has been falling rapidly, and the country is on track to achieve most of the UN Millennium Development Goals – including halving its 1990 poverty level.

In 2007, Cape Verde joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) and in 2008 the country graduated from Least Developed Country (LDC) to Middle Income Country (MIC) status.[66][67]

Cape Verde has significant cooperation with Portugal at every level of the economy, which has led it to link its currency first to the Portuguese escudo and, in 1999, to the euro. On 23 June 2008 Cape Verde became the 153rd member of the WTO.[68]

In early January 2018, the government announced that the minimum wage would be raised to 13,000 CVE (US$140 or EUR 130) per month, from 11,000 CVE, which was effective in mid-January 2018.[69][70]

Development

The European Commission's total allocation for the period of 2008–2013 foreseen for Cape Verde to address "poverty reduction, in particular in rural and peri-urban areas where women are heading the households, as well as good governance" amounts to €54.1 million.[71]

Tourism

Cape Verde's strategic location at the crossroads of mid-Atlantic air and sea lanes has been enhanced by significant improvements at Mindelo's harbour (Porto Grande) and at Sal's and Praia's international airports. A new international airport was opened in Boa Vista in December 2007 and on the island of São Vicente, the newest international airport (Cesária Évora Airport) in Cape Verde was opened in late 2009. Ship repair facilities at Mindelo were opened in 1983.[18]

The major ports are Mindelo and Praia, but all other islands have smaller port facilities. In addition to the international airport on Sal, airports have been built on all of the inhabited islands. All but the airports on Brava and Santo Antão enjoy scheduled air service. The archipelago has 3,050 km (1,895 mi) of roads, of which 1,010 km (628 mi) are paved, most using cobblestone.[18]

The country's future economic prospects depend heavily on the maintenance of aid flows, the encouragement of tourism, remittances, outsourcing labour to neighbouring African countries, and the momentum of the government's development programme.[18]

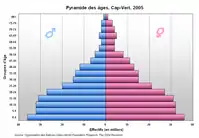

Demographics

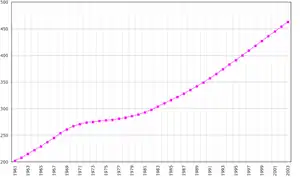

The official Census recorded that Cape Verde had a population of 512,096 in 2013.[72] A large proportion (236,000) of Cape Verdeans live on the main island, Santiago.[73]

Cape Verdeans are descendants of Africans (free or enslaved) and Europeans of various origins. There are also Cape Verdeans who have Jewish ancestors from North Africa, mainly on the islands of Boa Vista, Santiago and Santo Antão. A large part of Cape Verdeans emigrated abroad, mainly to the United States, Portugal and France, so that there are more Cape Verdeans residing abroad than at home.

Unlike countries on the African continent, there are no tribes in Cape Verde. On the other hand, the country's historical trajectory included, from the beginning, a process of social class formation. At this moment, the absence of a "bourgeoisie" can be seen, but the existence of several types of "petty bourgeoisie", numerically significant. The majority of the population is, however, made up of the peasantry and some working class.[74]

Largest cities or towns in Cape Verde Instituto Nacional de Estatística (Distribuição da população residente – RGPH 2010: População urbana) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Municipality | Pop. | ||||||

Praia  Mindelo |

1 | Praia | Praia | 127,832 |  Santa Maria  Assomada | ||||

| 2 | Mindelo | São Vicente | 70,468 | ||||||

| 3 | Santa Maria | Sal | 23,839 | ||||||

| 4 | Assomada | Santa Catarina | 12,026 | ||||||

| 5 | Porto Novo | Porto Novo | 9,430 | ||||||

| 6 | Pedra Badejo | Santa Cruz | 9,345 | ||||||

| 7 | São Filipe | São Filipe | 8,125 | ||||||

| 8 | Tarrafal | Tarrafal | 6,177 | ||||||

| 9 | Sal Rei | Boa Vista | 5,407 | ||||||

| 10 | Ribeira Grande | Ribeira Grande | 4,625 | ||||||

Languages

Cape Verde's official language is Portuguese.[1] It is the language of instruction and government. It is also used in newspapers, television, and radio.

Cape Verdean Creole (Kriolu) is used colloquially throughout Cape Verde and is the mother tongue of virtually all Cape Verdeans. The national constitution calls for measures to give it parity with Portuguese.[1] There is a substantial body of literature in Creole, especially in the Santiago Creole and the São Vicente Creole. Kriolu has been gaining prestige since the nation's independence from Portugal.

The differences between the forms of the language within the islands have been a major obstacle in the way of standardization of the language. Some people have advocated the development of two standards: a North (Barlavento) standard, centred on the São Vicente Creole, and a South (Sotavento) standard, centred on the Santiago Creole. Manuel Veiga, Ph.D., a linguist and Minister of Culture of Cape Verde, is the premier proponent of Kriolu's officialization and standardization.[75]

Religion

The vast majority of Cape Verdeans are Christian; reflecting centuries of Portuguese rule, Roman Catholics make up the single largest religious community, at just under 80 percent, as of 2010 (slightly down from 85 percent of the population in 2007).[77] Most other religious groups are Protestant, with the evangelical Church of the Nazarene forming the second largest community; other sizeable denominations are the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Assemblies of God, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[77] Islam is the largest minority religion.[77] Judaism had a historical presence during the colonial era.[78] Atheists constitute less than 1 percent of the population.[77] Many Cape Verdeans syncretize Christianity with indigenous African beliefs and customs.[79]

Emigration and immigration

.jpg.webp)

Almost twice as many Cape Verdeans live abroad (nearly one million) than in the country itself.[80] The islands have a long history of emigration and Cape Verdeans are highly dispersed worldwide, from Macau to Haiti and Argentina to Sweden.[81] The diaspora may be much larger than official statistics indicate, as, until independence in 1975, Cape Verdean immigrants had Portuguese passports.

The majority of Cape Verdeans live in the United States and Western Europe, with the former hosting the largest overseas population at 500,000. Most Cape Verdeans in the U.S. are concentrated in New England, particularly the cities of Providence, New Bedford, and Boston; Brockton, has the largest community of any American city (18,832).[82]

Cape Verdeans have been migrating to Massachusetts since the 1840s, but most of the current population arrived in the 1970s.[83] They are now one of the top ten immigrant groups in Boston, and the largest hailing from Africa. The first wave of Cape Verdean immigrants came to Massachusetts to work in the whaling industry.[83] When whaling declined, they moved into maritime jobs, seasonal agricultural work (like picking cranberries) , and factory work. The second wave of Cape Verdean immigrants arrived after Cape Verde gained independence in 1975. They also found work in factories, but as manufacturing plants closed down, they moved into the service industry in the 1990's. Cape Verdean immigrants have also developed a vibrant small business sector, including restaurants, groceries, real estate and insurance offices, and other enterprises.[83] Cape Verdean immigrants in the U.S. have a long history of enlistment in the U.S. military, with a presence in every major conflict from the Revolutionary War to the Vietnam War.[84]

Due to centuries of colonial ties, the second largest number of Cape Verdeans live in Portugal (150,000), with sizable communities in the former Portuguese colonies of Angola (45,000) and São Tomé and Príncipe (25,000). Major populations exist in countries with cultural and linguistic similarities, such as Spain (65,500), France (25,000), Senegal (25,000), and Italy (20,000). Other large communities live in the United Kingdom (35,500), the Netherlands (20,000, of which 15,000 are concentrated in Rotterdam), and Luxembourg and Scandinavia (7,000). Outside the U.S. and Europe, the biggest Cape Verdean populations are in Mexico (5,000) and Argentina (8,000).

Over the years, Cape Verde has increasingly become a net recipient of migrants, due to its relatively high per capita income, political and social stability, and civil freedom. Chinese make up a sizeable and important segment of the foreign population, while nearby West African countries account for most immigration. In the 21st century, a few thousand Europeans and Latin Americans have settled in the country, mostly professionals, entrepreneurs, and retirees. Over 22,000 foreign-born residents are naturalized, hailing from over 90 countries.

The Cape Verdean diaspora experience is reflected in many artistic and cultural expressions, most famously the song Sodade by Cesária Évora.[85]

Health

The infant mortality rate among Cape Verdean children between 0 and 5 years old is 15 per 1,000 live births according to the latest (2017) data from the National Statistics Bureau,[86] while the maternal mortality rate is 42 deaths per 100,000 live births. The HIV-AIDS prevalence rate among Cape Verdeans between 15 and 49 years old is 0.8%.[87]

According to the latest data (2017) from the National Statistics Bureau,[86] life expectancy at birth in Cape Verde is 76.2 years; that is, 72.2 years for males and 80.2 years for females. There are six hospitals in the Cape Verde archipelago: two central hospitals (one in the capital city of Praia and one in Mindelo, São Vicente) and four regional hospitals (one in Santa Catarina (northern Santiago region), one on São Antão, one on Fogo, and one on Sal). In addition, there are 28 health centers, 35 sanitation centers, and a variety of private clinics located throughout the archipelago.

Cape Verde's population is among the healthiest in Africa. Since its independence, it has greatly improved its health indicators. Besides having been promoted to the group of "medium development" countries in 2007, leaving the least developed countries category (becoming the second country to do so[88]), as of 2020 it was the 11th best ranked country in Africa in its Human Development Index.

The total expenditure on health was 7.1% of GDP (2015).

Education

Although the Cape Verdean educational system is similar to the Portuguese system, over the years the local universities have been increasingly adopting the American educational system; for instance, all ten existing universities in the country offer four-year bachelor's degree programs as opposed to five-year bachelor's degree programs that existed before 2010. Cape Verde has the second best educational system in Africa, after South Africa. Primary school education in Cape Verde is mandatory and free for children between the ages of six and fourteen years.[89]

In 2011, the net enrolment ratio for primary school was 85%.[89][90] Approximately 90% of the total population over 15 years of age is literate, and roughly 25% of the population holds a college degree; a significant number of these college graduates hold doctorate degrees in different academic fields. Textbooks have been made available to 90 percent of school children, and 98 percent of the teachers have attended in-service teacher training.[89] Although most children have access to education, some problems remain.[89] For example, there is insufficient spending on school materials, lunches, and books.[89]

As of October 2016, there were 69 secondary schools throughout the archipelago (including 19 private secondary schools) and at least 10 universities in the country, which are based on the two islands of Santiago and São Vicente.

In 2015, 23% of the Cape Verdean population had either attended or graduated from secondary schools. When it came to higher education, 9% of Cape Verdean men and 8% of Cape Verdean women held a bachelor's degree or had attended universities. The overall college education rate (i.e., college graduates and undergraduate students) in Cape Verde is about 24%, of the local college-age population.[91] The total expenditure on education was 5.6% of GDP (2010). The mean years of schooling of adults over 25 years is 12.

These trends were held in 2017. Cape Verde stands out in West Africa for the quality and inclusiveness of its higher education system. As of 2017, one in four young people attended university and one-third of students opted for fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.[65] Women made up one-third of students but two-thirds of graduates in 2018.[65]

Science and technology

In 2011, Cape Verde devoted just 0.07% of its GDP to research and development, among the lowest rates in West Africa. The Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Culture plan to strengthen the research and academic sectors by emphasizing greater mobility, through exchange programmes and international cooperation agreements. As part of this strategy, Cape Verde is participating in the Ibero-American academic mobility programme that expects to mobilize 200,000 academics between 2015 and 2020.[92] Cape Verde was ranked 89th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021.[93]

Cape Verde counted 25 researchers in 2011, a researcher density of 51 per million inhabitants. The world average was 1,083 per million in 2013. All 25 researchers were working in the government sector in 2011 and one in three were women (36%). There was no research being conducted in either medical or agricultural sciences. Of the eight engineers involved in research and development, one was a woman. Three of the five researchers working in natural sciences were women, as were three of the six social scientists and two of the five researchers from the humanities.[92]

In 2015, the government announced a project to build a technology park for business, research, and development. As of late 2020, the project, now named TechPark Cabo Verde, is slated for completion in June 2022. The project is funded by both the African Development Bank and the government of Cape Verde. The goal of the endeavour, according to Cape Verde Minister of Finance Olavo Correia, is "to attract large international companies to set up shop [in order] to help local companies and start-ups become more competitive".[94]

Cape Verde has a high rate of internet penetration and a growing mobile phone market. The government has invested in improving ICT infrastructure and has created a number of initiatives to promote the development of the digital economy. The digital economy has the potential to create jobs, boost economic growth, and improve the quality of life for people in Cape Verde.[95]

Culture

The culture of Cape Verde is characterized by a mixture of African and European elements. This is not a sum of two cultures living side by side, but a new culture resulting from an exchange that began in the 15th century.

Cape Verdean social and cultural patterns are unique.[44] Football games and church activities are typical sources of social interaction and entertainment.[44] The traditional walk around the praça (town square) to meet friends is practised regularly in Cape Verde towns.[44]

Media

In towns with electricity, television is available on three channels; one state-owned (RTC – TCV) and three foreign-owned: RTI Cabo Verde launched by the Portuguese-based RTI in 2005; Record Cabo Verde, launched by the Brazilian-based Rede Record on 31 March 2007; and as of 2016, TV CPLP. Premium channels available include the Cape Verdean versions of Boom TV and Zap Cabo Verde, two channels owned by Brazil's Record.[97] Other premium channels are available in Cape Verde, especially satellite network channels which are common in hotels and villas, though availability is otherwise limited. One such channel is RDP África, the African version of the Portuguese radio station RDP.

As of early 2023, about 99% of the Cape Verdean population own an active cellular phone, 70% have access to the Internet, 11% own a landline telephone, and 2% subscribe to local cable TV. In 2003, Cape Verde had 71,700 main line telephones with an additional 53,300 cellular phones in use throughout the country.

In 2004, there were seven radio stations, six independent and one state-owned. The media is operated by the Cape-Verdean News Agency (secondarily as Inforpress). Nationwide radio stations include RCV, RCV+, Radio Kriola, and the religious station Radio Nova. Local radio stations include Rádio Praia, the first radio station in Cape Verde; Praia FM, the first FM station in the nation; Rádio Barlavento, Rádio Clube do Mindelo and Radio Morabeza in Mindelo.

Music

.jpg.webp)

The Cape Verdean people are known for their musicality, well expressed by popular manifestations such as the Carnival of Mindelo. Cape Verde music incorporates "African, Portuguese and Brazilian influences."[98] Cape Verde's quintessential national music is the morna, a melancholy and lyrical song form typically sung in Cape Verdean Creole. The most popular music genre after morna is the coladeira, followed by funaná and batuque music. Cesária Évora was the best-known Cape Verdean singer in the world, known as the "barefoot diva", because she liked to perform barefooted on stage. She was also referred to as "The Queen of Morna"[99] as opposed to her uncle Bana, who was referred to as "King of Morna". The international success of Cesária Évora has made other Cape Verdean artists, or descendants of Cape Verdeans born in Portugal, gain more space in the music market. Examples of this are singers Sara Tavares, Lura and Mayra Andrade.

Another great exponent of traditional music from Cape Verde was Antonio Vicente Lopes, better known as Travadinha, and Ildo Lobo, who died in 2004. The House of Culture in the center of the city of Praia is called Ildo Lobo House of Culture, in his honour.

There are also well-known artists born to Cape Verdean parents who excelled themselves in the international music scene. Amongst these artists are jazz pianist Horace Silver, Duke Ellington's saxophonist Paul Gonsalves, Teófilo Chantre, Paul Pena, the Tavares brothers and singer Lura.

Dance

Cape Verdean traditional dance is a mix of West and Central African influences. The most popular dance style in Cape Verde is called “Funana” which originated on the island of Santiago and is danced in pairs with fast hip movements and a lively rhythm. Another popular dance style is “Coladeira” which is a slower dance style that originated on the island of Sao Vicente. “Batuque” is another traditional Cape Verdean dance style that originated on the island of Santiago and involves a lot of hip movement and percussion. “Morna” is another popular Cape Verdean dance style that originated on the island of Boa Vista and has a slow tempo with a melancholic melody. Zouk and Kizomba are newer popular dance style in Cape Verde that originated in other countries.

Literature

.jpg.webp)

Cape Verdean literature is one of the richest of Lusophone Africa. Famous poets include Paulino Vieira, Manuel de Novas, Sergio Frusoni, Eugénio Tavares, and B. Léza, and famous authors include Baltasar Lopes da Silva, António Aurélio Gonçalves, Manuel Lopes, Orlanda Amarílis, Henrique Teixeira de Sousa, Arménio Vieira, Kaoberdiano Dambará, Dr. Azágua, and Germano Almeida. The first novel written by a woman from Cabo Verde was A Louca de Serrano by Dina Salústio; its translation, as The Madwoman of Serrano, was the first translation of any Cabo Verdean novel to English.[100][101]

Cinema

The Carnival and the island of São Vicente are portrayed in the 2015 feature documentary Tchindas, nominated at the 12th Africa Movie Academy Awards.

Cuisine

The Cape Verde diet is mostly based on fish and staple foods like corn and rice. Vegetables available during most of the year are potatoes, onions, tomatoes, manioc, cabbage, kale, and dried beans. Fruits such as bananas and papayas are available year-round, while others like mangoes and avocados are seasonal.[44]

A popular dish served in Cape Verde is cachupa, a slow-cooked stew of corn (hominy), beans, and fish or meat. A common appetizer is the pastel, a pastry shell filled with fish or meat which is then fried.[44]

Sports

The country's most successful sports team is the Cape Verde national basketball team, which won the bronze medal at the FIBA Africa Championship 2007, after beating Egypt in its last game. The country's most well-known player is Walter Tavares, who plays for Real Madrid of Spain.

Cape Verde is famous for wave sailing[102] (a type of windsurfing) and kiteboarding.[103] Josh Angulo, a Hawaiian and 2009 PWA Wave World Champion, has done much to promote the archipelago as a windsurfing destination.[102] Mitu Monteiro, a local kitesurfer, was the 2008 Kite Surfing World Champion in the wave discipline.

The Cape Verde national football team, nicknamed the Tubarões Azuis (Blue Sharks), is the national team of Cape Verde and is controlled by the Cape Verdean Football Federation. The team has played at three Africa Cup of Nations, in 2013, 2015, and 2021.[104]

The country has competed at every Summer Olympics since 1996. In 2016, Gracelino Barbosa became the first Cape Verdean to win a medal at the Paralympic Games.[105]

Transport

Ports

There are four international ports: Mindelo, Praia, Palmeira and Sal Rei. Mindelo on São Vicente is the main port for cruise ships and the terminus for the ferry service to Santo Antão. Praia on Santiago is the main hub for local ferry services to other islands. Palmeira on Sal supplies fuel for the main airport on the island, Amílcar Cabral International Airport, and is important for the hotel construction taking place on the island. Porto Novo on Santo Antão is the only source for imports and exports of produce from the island as well as passenger traffic since the closure of the airstrip at Ponta do Sol.

There are smaller harbours, essentially single jetties at Tarrafal on São Nicolau, Sal Rei on Boa Vista, Vila do Maio (Porto Inglês) on Maio, São Filipe on Fogo and Furna on Brava. These act as terminals for the inter-island ferry services, which carry both freight and passengers. The pier at Santa Maria on Sal used by both fishing and dive boats has been rehabilitated.

Airports

There were seven operational airports as of 2014 – four international and three domestic. Two others were non-operational, one on Brava and the other on Santo Antão closed for safety reasons.

Due to its geographical location, Cape Verde is often flown over by transatlantic airliners. It is part of the conventional air traffic route from Europe to South America, which goes from southern Portugal via the Canary Islands and Cape Verde to northern Brazil.

International airports

- Amílcar Cabral International Airport, Sal Island

- Nelson Mandela International Airport, Santiago Island

- Aristides Pereira International Airport, Boa Vista Island

- Cesária Évora Airport, São Vicente Island

Aerial drones

Small unmanned flying drones able to carry up to 5kg were being used experimentally for tasks such as delivering medicines between the islands in 2021.[106]

See also

References

- "Constituição da República de Cabo Verde" (PDF). ICRC databases on international humanitarian law. Article 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- "INE APRESENTA OS RESULTADOS DEFINITIVOS DO V RECENSEAMENTO GERAL DA POPULAÇÃO E HABITAÇÃO (RGPH-2021)". Instituto Nacional de Estatística - INE. 4 April 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- John Kerry (8 July 2014). "On the Occasion of the Republic of Cabo Verde's National Day". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

On behalf of President Obama and the people of the United States, I send best wishes to Cabo Verdeans as you celebrate 39 years of independence on July 5.

- Amorim Neto, Octávio; Costa Lobo, Marina (2010). "Between Constitutional Diffusion and Local Politics: Semi-Presidentialism in Portuguese-Speaking Countries". SSRN 1644026.

- "Population, total - Cabo Verde". World Bank. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- "World Economic Outlook database: April 2022". www.imf.org. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "GINI index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Tanya Basu (12 December 2013). "Cape Verde Gets New Name: 5 Things to Know About How Maps Change". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- "Constituição da República de Cabo Verde" (PDF). ICRC databases on international humanitarian law. Article 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Archived 14 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine Republic of Cape Verde Islands & Municipalities, CityPopulation.de, 14.01.2023.

- Lobban, p. 4 Archived 25 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Cabo Verde põe fim à tradução da sua designação oficial" [Cabo Verde puts an end to translation of its official designation] (in Portuguese). Panapress. 31 October 2013. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "Cabo Verde – Cultural life". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

Although there is no conclusive evidence that the islands were inhabited before the arrival of the Portuguese, cases may be made for visits by Phoenicians, Moors, and Africans in previous centuries.

- "Cape Verde, Country on the West Coast of Africa | South African History Online". South Africa History Online. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

The early settlement in Cape Verde by Arab and African fishermen has only been related through oral history, and remains a part of the mythological stories of origin of the archipelago. It is generally agreed that the Islands where [sic] uninhabited when the Portuguese first landed in 1456.

- Halter, Marilyn (2013). "Cape Verdeans and Cape Verdean Americans, 1870–1940". In Barkan, Elliott Robert (ed.). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO Publisher. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-59884-219-7. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

Although Cape Verdean folklore includes stories of landings by Arab and African fishermen prior to the sighting of the archipelago by Portuguese navigators in the mid-fifteenth century, most historians concur that it was uninhabited when the Portuguese began to settle there.

- Carta regia (royal letter) of 19 September 1462

- Cape Verde background note Archived 4 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine . United States Department of State (July 2008).

- Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 17. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of HMS Beagle round the world – Chapter 1 at Wikisource, top part

- "Pedro Pires wins Cape Verde runoff". New Bedford Standard-Times. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- "Cape Verde profile – Timeline". BBC News. 8 May 2018. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- "Cape Verde President Fonseca on track to win re-election". Reuters. 3 October 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- "Cape Verde opposition wins back parliament". Reuters. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- "Cape Verde ruling party retains power after winning legislative vote". 19 April 2021. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- Sharma, Neha (27 August 2021). "Cabo Verde: 150th state to ratify the 2005 UNESCO Convention". fundsforNGOs News. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- Rodrigues, Julio (18 October 2021). "Opposition candidate Neves wins Cape Verde election". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- "Cape Verde's new president Jose Maria Neves to be sworn in on Nov. 9". www.news.cn. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- "Constitution of Cape Verde" (PDF). 1992. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, Nazifa Alizada, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Allen Hicken, Garry Hindle, Nina Ilchenko, Joshua Krusell, Anna Lührmann, Seraphine F. Maerz, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Juraj Medzihorsky, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Josefine Pernes, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Aksel Sundström, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Tore Wig, Steven Wilson and Daniel Ziblatt. 2021. "V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v11.1" Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds21 Archived 7 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Opposition returns to power in Cape Verde after 15 years". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "Cape Verde country profile". BBC News. 5 December 2018. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- "Cape Verde opens first embassy in Nigeria | Premium Times Nigeria". 20 November 2021. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- "Remarks by the President After Meeting with African Leaders". Obama White House Archives. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "2016 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- "2013 Ibrahim Index of African Governance" (PDF). Mo Ibrahim Foundation. October 2013. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "Cape Verde | 2010 Index of Economic Freedom". Heritage.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- "World Economic Forum : The Global Information Technology Report 2010–2011" (PDF). Weform.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Percival, Debra (25 May 2008). "Cape Verde-EU 'Special Partnership' takes shape". The Courier. European Commission. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011.

- "Cape Verde could seek EU membership this year". Eubusiness.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Cape Verde becomes the 119th State to join the Rome Statute system". icc-cpi.int. International Criminal Court. 13 October 2011. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011.

- "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Eleven shot dead in Cape Verde, including two Spanish citizens". Reuters. 27 April 2016. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "The Peace Corps Welcomes You to Cape Verde" (PDF). Peace Corps. April 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2017. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Pim et al., 2008, p. 422

- Carracedo, Juan Carlos; Troll, Valentin R. (2021), "North-East Atlantic Islands: The Macaronesian Archipelagos", Encyclopedia of Geology, Elsevier, pp. 674–699, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102908-4.00027-8, ISBN 978-0-08-102909-1, S2CID 226588940, archived from the original on 7 August 2023, retrieved 16 March 2021

- R. Ramalho et al., 2010

- Le Bas, T.P. (2007), "Slope Failures on the Flanks of Southern Cape Verde Islands", in Lykousis, Vasilios (ed.), Submarine mass movements and their consequences: 3rd international symposium, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-6511-8

- "Normais Climatológicas". www.inmg.gov.cv (in European Portuguese). Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- Halter, Marilyn (2013). "Cape Verdeans and Cape Verdean Americans, 1870–1940". In Barkan, Elliott Robert (ed.). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO Publisher. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-59884-219-7. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

The Cape Verde Islands...chain...was named after the westernmost tip of mainland Africa, the Cape Vert, and[,] while the term "Verde" (green) gives the impression of a lush and verdant landscape, nothing could be further from the truth. The islands are essentially a maritime extension of the dry and dusty Sahel desert region, and the terrain is so arid and mountainous that less than 2 percent of the land is suitable for farming.

- Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- "Klimatafel von Santa Maria / Sal (Int.Flugh.) / Kapverden (Rep. Kap Verde)" (PDF). DwD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- "Klimatafel von Praia / Sao Tiago / Kapverden (Rep. Kap Verde)" (PDF). DwD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- "Klimatafel von Mindelo / Sao Vicente / Kapverden (Rep. Kap Verde)" (PDF). DwD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- "A sinking feeling: why is the president of the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru so concerned about climate change?". New York Times Upfront. 14 November 2011. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Philip Andrew Churm (22 January 2023). "UN chief arrives in Cabo Verde to raise concerns about climate change". Africanews. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- "Cabo Verde 'on the frontlines' of climate crisis, says Guterres ahead of Ocean Summit | UN News". news.un.org. 21 January 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- "Portugal leads way for Europe with Cape Verde debt-for-nature swap". euronews. 26 January 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- "Endemic Bird Areas: Cape Verde Islands". Birdlife.org. Archived from the original on 2 January 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- 2010 Census — source: Instituto Nacional de Estatistica.

- 2021 Census — source: Instituto Nacional de Estatistica.

- See Carlos Ferreira Couto, Incerteza, adaptabilidade e inovação na sociedade rural da Ilha de Santiago de Cabo Verde, Lisbon: Fundação Galouste Gulbenkian, 2010

- See now Brígida Rocha Brito and others, Turismo em Meio Insular Africano: Potencialidades, constrangimentos e impactos, Lisbon: Gerpress, 2010

- "Turbines arrive for ground-breaking wind farm in Africa – InfraCo Limited". Infracoafrica.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012.

- Schneegans, S.; Straza, T.; Lewis, J., eds. (2021). UNESCO Science Report: the Race Against Time for Smarter Development. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100450-6. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- "MFW4A". MFW4A. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- "Cabo Verde – Data". World Bank. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- "Cape Verde to join WTO on 23 July 2008". WTO News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- "Cape Verde government raises minimum wage to 13,000 escudos". MacauHub. 8 January 2018. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- "Governo vai aumentar salário mínimo nacional de 11 para 13 mil escudos". A Semana (in Portuguese). 6 January 2018. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- "European Commission". Ec.europa.eu. 21 December 2012. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatistica, Praia

- "Cape Verde: Population". caperverde.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "Michel Lesourd, État et société aux îles du Cap Vert, Paris: Karthala, 1995".

- Amado, Abel D. (2015), The Illegible State in Cape Verde: Language Policy and the Quality of Democracy Archived 15 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Boston University, a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

- (CABO VERDE) Archived 19 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- "State.gov". State.gov. 14 September 2007. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Jews in Cape Verde Archived 8 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine", by Louise Werlin

- "Background Note: Cape Verde". State.gov. 15 June 2010. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Jorgen Carling, 2004, pp. 113–132

- Cape Verdean Americans – History, Modern era, The first cape verdeans in america, Everyculture.com

- "Cape Verdeans in Brockton". Boston Planning & Development Agency. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "A History of Immigration to Boston: Eras, Ethnic Groups, and Places". Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas. 28 May 2019. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- "Cape Verdeans: Cape Verdean Veterans". Sites.google.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012.

- Kimeria, Ciku (13 April 2019). "Cesaria, the unlikely heroine for the country that treasures her indomitable spirit". Quartz Africa. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Início – INE". Ine.cv. 20 June 2014. Archived from the original on 20 February 2001. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- "UN advocate salutes Cape Verde's graduation from category of poorest States" Archived 24 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, UN News Centre, 14 June 2007.

- "Cape Verde" Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor (2001). Bureau of International Labor Affairs, United States Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "World Development Indicators | Data". Data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- "Instituto Nacional de Estatística Cabo Verde". Archived from the original on 20 February 2001.

- UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). UNESCO. 2015. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Global Innovation Index 2021". World Intellectual Property Organization. United Nations. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Cape Verde: small country, big digital ambitions". Resilient Digital Africa. resilient.digital-africa.co. 26 November 2021. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Cabo Verde – Digital Economy". www.trade.gov. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- "Cape Verde" Archived 25 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. United States Bureau of Consular Affairs (5 May 2008). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "TV Record Cabo Verde disponível também nos canais a cabo em Cabo Verde". ZAP TV and BOOM TV. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016.

- Peter Manuel (1988). Popular Musics of the Non-Western World. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-0-19-506334-9. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- Pareles, Jon (19 December 2011). "Cesária Évora, Singer From Cape Verde, Dies at 70 (Published 2011)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- "The Madwoman of Serrano by Dina Salústio : Our Books :: Dedalus Books, Publishers of Literary Fiction". www.dedalusbooks.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- Soutar, Jethro (19 July 2017). "Translating Dina Salústio, Cape Verde's First Female Novelist". Brittle Paper. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- "Cape Verde windsurfing Holidays". www.planetwindsurfholidays.com. Planet Travel Ltd, Brighton (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- "Become a Waver Rider Kiteboarding in Cape Verde | 57hours". 57hours - Discover amazing outdoor adventures. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- "Africa Cup of Nations: Cape Verde and Ethiopia qualify". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Rio 2016: Cabo-verdiano conquista primeira medalha dos PALOP na Paralimpíada". Deutsche Welle (in Portuguese). 2016. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- "Drone delivers medical supplies to remote islands". BBC News. 31 December 2021. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

Bibliography

- Pim, J.; Pierce, C.; Watts, A. B.; Grevemeyer, I.; Krabbenhoeft, A. (5 May 2008). "Crustal structure and origin of the Cape Verde Rise" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 272 (1–2): 422–428. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.272..422P. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.05.012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2011.

- Carling, Jorgen (2004). "Emigration, Return and Development in Cape Verde: The Impact of Closing Borders". Population, Space and Place. 55 (10): 113–132. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199901)55:1<117::AID-JCLP12>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 10100838.

- Ramalho, R.; Helffrich, G.; Schmidt, D.; Vance, D. (2010). "Tracers of Uplift and Subsidence in the Cape Verde Archipelago". Journal of the Geological Society. 167 (3): 519–538. Bibcode:2010JGSoc.167..519R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.173.3419. doi:10.1144/0016-76492009-056. S2CID 140566236.

External links

Wikimedia Atlas of Cape Verde

Wikimedia Atlas of Cape Verde- Official website of the Government of Cape Verde

- Cape Verde at Curlie