Rickettsia rickettsii

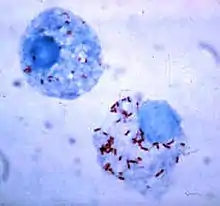

Rickettsia rickettsii (abbreviated as R. rickettsii) is a Gram-negative, intracellular, coccobacillus bacterium that is around 0.8 to 2.0 μm long. R. rickettsii is the causative agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. R. rickettsii is one of the most pathogenic Rickettsia strains. It affects a large majority of the Western Hemisphere and small portions of the Eastern Hemisphere.[1]

| Rickettsia rickettsii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Rickettsiales |

| Family: | Rickettsiaceae |

| Genus: | Rickettsia |

| Species group: | Spotted fever group |

| Species: | R. rickettsii |

| Binomial name | |

| Rickettsia rickettsii Brumpt, 1922 | |

History

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) first emerged in the Idaho Valley in 1896. At that time, not much information was known about the disease; it was originally called Black Measles because patients had a characteristic spotted rash appearance throughout their body. The first clinical description of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever was reported in 1899 by Edward E. Maxey.

Howard Ricketts (1871–1910), an associate professor of pathology at the University of Chicago in 1902, was the first to identify and study R. rickettsii. At this time, the trademark rash now began to slowly emerge in the western Montana area, with an 80-90% mortality rate. His research entailed interviewing victims of the disease and collecting and studying infected animals. He was also known to inject himself with pathogens to measure their effects. Unfortunately, his research was cut short by his death, likely from an insect bite.

Simeon Burt Wolbach is credited for the first detailed description of the pathogenic agent that causes R. rickettsii in 1919. He clearly recognized it as an intracellular bacterium which was seen most frequently in endothelial cells.

On A Global Scale

R. rickettsii is found on every continent, except Antarctica. The disease was first discovered in North America and since then has been identified in almost every corner of the earth. The spread of R. rickettsii is likely due to the migration of humans and animals around the globe. However, R. rickettsii tends to thrive in warm damp places and this can be seen by contraction rates around the world.[2] Environments are constantly changing so the fluctuation of the disease is never constant in a population and this correlates to the evolution of R. rickettsii.

Pathogen life cycle

The most common hosts for the R. rickettsii bacteria are ticks.[3] Ticks that carry R. rickettsia fall into the family of Ixodidae ticks, also known as "hard-bodied" ticks.[4] Ticks are vectors, reservoirs, and amplifiers of this disease.[3]

There are currently three known tick specifics that commonly carry R. rickettsii.[4]

- American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) [4]

- Rocky Mountain Wood Tick (Dermacentor andersoni)[4]

- Brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguine). [4]

Ticks can contract R. rickettsii by many means. First, an uninfected tick can become infected when feeding on the blood of an infected vertebrate host; such as a rabbit, during the larval or nymph stages, this mode of transmission is called transstadial transmission. Once a tick becomes infected with this pathogen, they are infected for life. Both the American dog tick and the Rocky Mountain wood tick serve as long-term reservoirs for Rickettsia rickettsii, in which the organism resides in the tick posterior diverticula of the midgut, the small intestine and the ovaries. In addition, an infected male tick can transmit the organism to an uninfected female during mating. Once infected, the female tick can transmit the infection to her offspring, in a process known as transovarian passage.[5]

Transmission in mammals

Due to its confinement in the midgut and small intestine, Rickettsia rickettsii can be transmitted to mammals, including humans. Transmission to mammals can occur in multiple ways. One way of contraction is through the contact of an infected host feces to an uninfected host. If an infected host's feces comes into contact with an open skin wound, it is possible for the disease to be transmitted. Additionally, an uninfected host can become infected with R. rickettsii when eating food that contains the feces of the infected vector.

Another way of contraction is by the bite of an infected tick. After getting bitten by an infected tick, R. rickettsiae is transmitted to the bloodstream by tick salivary secretions.

R. rickettsii has also been found to distort the sex ratio of their hosts. This is done by eradicating males and undergoing parthenogenesis; this is done primarily via horizontal gene transfer. Female hosts can pass the R. rickettsii gene to their offspring, giving R. rickettsii bacteria yet another way to infect hosts.[6]

Having multiple modes of transmission ensures the persistence of R. rickettsii in a population. Also, having multiple modes of transmission helps the disease adapt better to new environments and prevents it from becoming eradicated. R. rickettsii has evolved a number of strategic mechanisms or virulence factors that allow it to invade the host immune system and successfully infect the host.

Genomic Structure

R. rickettsii is an obligate intracellular alpha proteobacteria that belongs to the Rickettsiacea family. It is a pleomorphic, Gram-negative coccobacillus that multiplies by binary fission. R. rickettsii is shown to have a genome size of around 2,100 kb. This number was determined via pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.[7]

Virulence

Since R. rickettsii needs a moving vector to contract the disease to a viable host it is more likely that this pathogen has moderately low virulence levels. This idea is supported by the tradeoff hypothesis which suggests that virulence of a pathogen will evolve until the level of virulence balances out with the level of transmission to maximize the spread of the pathogen. R. rickettsii invades the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels in the hosts body. Endothelial cells are not phagocytic in nature; however, after attachment to the cell surface, the pathogen causes changes in the host cell cytoskeleton that induces phagocytosis. Since the bacteria can now induce phagocytosis the R. rickettsii gene can be replicated and further invade other cells in the host's body.

Clinical manifestations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that the diagnosis of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever must be made based on the clinical signs and symptoms of the patient and then later be confirmed using specialized laboratory tests. However, the diagnosis of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is often misdiagnosed due to its non-specific onset. The majority of infections from R. rickettsii occur during the warmer months between April and September. Symptoms can take a 1-2 days to 2 weeks to present themselves within the host.[8] The diagnosis of RMSF is easier when there is a known history of a tick bite or if the rash is already apparent on the affected individual.[9] If not treated properly, the illness may become serious, leading to hospitalization and possible fatality.

Signs and Symptoms

During the initial stages of the disease, the patient may experience headache, muscle ache, chills, and high fever. Other early symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and conjunctival injection (red eyes). Most people infected by R. rickettsii develop a spotted rash, that begins to appear 2-4 days after the individual develops fever. If left untreated, more severe symptoms may develop; these symptoms may include insomnia, compromised mental ability, coma, and damage to the heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, or additional organs.[10][8] During the late stages of the disease, diarrhea, abdominal and joint pain, and pinpoint reddish lesions (petechiae) can be observed.

Rash

The classic Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever rash occurs in about 90% of patients and develops 2 to 5 days after the onset of fever. The rash can differ greatly in appearance along the progress of the R. rickettsii infection.[10] It is not itchy and starts out as flat pink macules located on the affected individual's hands, feet, arms, and legs.[9] During the course of the disease, the rash will take on a more darkened reddish purple spotted appearance and become more evenly distributed.

Severe infections

Patients with severe infections may require hospitalization. The later, more severe symptoms occur in response to of thrombosis (blood clotting) caused by R. rickettsii targeting endothelial cells in vascular tissue.[8][11] They may become hyponatremic, experience elevated liver enzymes, and other more pronounced symptoms. It is not uncommon for severe cases to involve the respiratory system, central nervous system, gastrointestinal system or the renal system complications. This disease is worst for elderly patients, males, African-Americans, alcoholics, and patients with G6PD deficiency. The mortality rate for RMSF is 3-5 percent in all cases but 13-25 in untreated cases.[12] Deaths usually are caused by heart and kidney failure.[5]

Diagnosis and treatment

Laboratory confirmation

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is often diagnosed using an indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), which is considered the reference standard by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The IFA will detect an increase in IgG or IgM antibodies in the bloodstream.

A more specific lab test used in diagnosing Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is polymerase chain reaction or PCR which can detect the presence of rickettiae DNA.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining is another diagnostic approach where a skin biopsy is taken of the spotted rash; however, accuracy is only 70%.

Antibiotics

Doxycycline and Chloramphenicol are the most common drugs of choice for reducing the symptoms associated with RMSF. When it is suspected that a patient may have RMSF, it is crucial that antibiotic therapy be administered promptly. Failure to receive antibiotic therapy, especially during the initial stages of the disease, may lead to end-organ failure (heart, kidney, lungs) meningitis, brain damage, shock, and even death.

Preventative Measures

The main preventive measures are taken by containing and eliminating the carrier of the pathogen. The primary prevention tactic used to prevent Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) is to prevent tick bites. Since tick bites transfer the causative agent, R. rickettsii, it is recommended to apply preventative measures year-round, despite the probability of infection increasing from April through September. Before going outside, it is important to remain aware of ticks in wooded or grassy areas, in particular leaf litter. By clearing leaf piles from the yard this will lessen the likelihood of ticks being in close proximity. They can also be found on animals. There are treatments used, such as permethrin or insect repellent, that are applied to clothing to deter ticks from latching onto a new host. In addition, wearing long sleeve shirts and pants when in grassy areas provides a barrier from possible tick bites.[13]

Once coming inside, examine clothing, pets, and body for ticks. Ticks can be carried into a home through clothing or pets, and attach later to a new host. When washing clothing, hot water and high heat will ensure that any ticks carried inside do not survive. When examining the body, look in keys areas such as in hair, ears or belly buttons, as well as armpits, behind the knee, and around the waist. This can be done before showering, as showering two hours after being outdoors can reduce the risk of disease by washing away unattached ticks.[13]

If a tick is found on the body, it is important to remove it immediately. Using a pair of tweezers, grab the tick as close to the skin as possible and pulling upward with even pressure. Once removed, wash the area with soap and water and dispose of the tick by flushing it down the toilet, putting it in rubbing alcohol, placing in a sealed bag, or wrapping it tightly in tape. If the tick is not removed in one piece, remove the remaining parts with the tweezers; however, if it cannot be or is difficult to remove, leave it.[14]

References

- Perlman SJ, Hunter MS, Zchori-Fein E (September 2006). "The emerging diversity of Rickettsia". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 273 (1598): 2097–2106. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3541. PMC 1635513. PMID 16901827.

- Openshaw JJ, Swerdlow DL, Krebs JW, Holman RC, Mandel E, Harvey A, et al. (July 2010). "Rocky mountain spotted fever in the United States, 2000-2007: interpreting contemporary increases in incidence". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 83 (1): 174–182. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0752. PMC 2912596. PMID 20595498.

- Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D (October 2005). "Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 719–756. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.719-756.2005. PMC 1265907. PMID 16223955.

- Parola P, Davoust B, Raoult D (2005-06-01). "Tick- and flea-borne rickettsial emerging zoonoses". Veterinary Research. 36 (3): 469–492. doi:10.1051/vetres:2005004. PMID 15845235.

- Tortora GJ, Funke BR, Case CL (2013). Microbiology: An Introduction. United States of America: Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 661–662. ISBN 978-0-321-73360-3.

- Weinert LA, Werren JH, Aebi A, Stone GN, Jiggins FM (February 2009). "Evolution and diversity of Rickettsia bacteria". BMC Biology. 7: 6. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-6. PMC 2662801. PMID 19187530.

- Myers WF, Baca OG, Wisseman CL (October 1980). "Genome size of the rickettsia Coxiella burnetii". Journal of Bacteriology. 144 (1): 460–461. doi:10.1128/jb.144.1.460-461.1980. PMC 294686. PMID 7419494.

- "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever", Red Book (2018), American Academy of Pediatrics, pp. 697–700, 2018-05-01, retrieved 2023-10-21

- "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever", SpringerReference, Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, retrieved 2023-10-21

- CDC (2019-05-07). "Rocky Mountain spotted fever home | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2023-10-21.

- Kristof, M. Nathan; Allen, Paige E.; Yutzy, Lane D.; Thibodaux, Brandon; Paddock, Christopher D.; Martinez, Juan J. (2021-02-19). "Significant Growth by Rickettsia Species within Human Macrophage-Like Cells Is a Phenotype Correlated with the Ability to Cause Disease in Mammals". Pathogens. 10 (2): 228. doi:10.3390/pathogens10020228. ISSN 2076-0817.

- "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever", SpringerReference, Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, retrieved 2023-10-21

- CDC (2021-05-27). "Rocky Mountain spotted fever prevention | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- CDC (2022-05-13). "Tick removal | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

Further reading

- Dumbler SJ, Walker DH (2006). "Order II. Rickettsiales Gieszczkiewicz 1939..". In Garrity G, Brenner DJ, Staley JT, Krieg NR, Boone DR, Vos PD, et al. (eds.). Bergey's Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology: Volume Two: The Proteobacteria (Part C). Springer. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-387-29298-4.

- Weiss K (1988). "The Role of Rickettsioses in History". In Walker DH (ed.). Biology of Rickettsial Diseases. CRC Press. pp. 2–14. ISBN 978-0-8493-4382-7.

- Weiss E (1988). "History of Rickettsiology". Biology of Rickettsial Diseases. pp. 15–32.

- Wilson BA, Salyers AA, Whitt DD, Winkler ME (2011). Bacterial Pathogenesis: A Molecular Approach (3rd ed.). Amer Society for Microbiology. ISBN 978-1-55581-418-2.

- Todar K (2008–2012). "Rickettsial Diseases, including Typhus and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology.

External links

- "Rickettsia rickettsii genomes and related information". PATRIC, Bioinformatics Resource Center. NIAID.

- "Rickettsia rickettsii: The Cause of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". Multiple Organisms: Organismal Biology. University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. 2007.

- "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 21 November 2013.