Queensland tick typhus

Queensland tick typhus[2] is a zoonotic disease[3] caused by the bacterium Rickettsia australis.[4] It is transmitted by the ticks Ixodes holocyclus and Ixodes tasmani.[5]

| Queensland tick typhus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Australian tick typhus or Rickettsial spotted fever[1] |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Signs and symptoms

Queensland tick typhus is a tick-borne disease. Onset of the illness is variable; there is an incubation period of 2 to 14 days after being bitten by the infected tick.[6] The clinical features of this illness include fever, headache, an eschar at the site of the tick bite, erythematous eruption[6] and satellite lymphadenopathy.[7] Queensland tick typhus symptomatically resembles Rocky Mountain spotted fever, a less severe tick-borne disease.[7] If left untreated for longer than one to two weeks, the disease can take longer to recover from and pose a heightened risk of pneumonitis, encephalitis, septic shock, or even death. In some cases, even after the initial rash is cleared, the person may still experience prolonged lethargy or fatigue, which is common in such rickettsial infections.[6]

Causes

Queensland tick typhus is caused by the bacteria Rickettsia australis from the genus Rickettsia.[8]

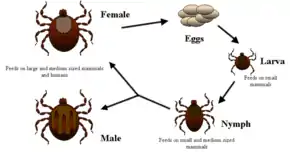

Tick life cycle

The tick life cycle consists of four stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult.[9] An adult female tick can lay over a thousand eggs in her lifetime.[10] Once a tick hatches from an egg, it enters the larvae stage, where it must attach to any available host and begin feeding. After it has fed, it detaches and molts, entering the larger nymph stage. In this stage it must reattach to a larger host and feed again, whereupon it detaches and molts again. This results in the adult stage, where it feeds one last time and is able to sexually reproduce.[9]

The stage when ticks are most able to transmit this disease is the nymph stage. They are also the most dangerous in this stage since they are usually less than two millimeters in size and can stay virtually undetected until they are done feeding.

Transmission

Queensland tick typhus is transmitted primarily by two types of tick: Ixodes holocyclus and Ixodes tasmani. After the initial attachment to a host, depending on the species and life stage of the tick, it takes anywhere from 10 minutes to 2 hours for it to begin to feed.[11] Once a tick attaches, it can stay on a host for about 12 to 18 hours and then falls off when full. A tick must be attached for a long period of time to transmit bacteria. A tick that appears flat and small probably has not eaten yet.[12]

Pathogenesis

After transmission from the infected tick, the bacterium Rickettsia australis enters the body via the bloodstream. The first sign of disease is damage to the skin's microcirculation, which results in a rash.[13] From there, the damage continues further into vital organs and can ultimately result in sepsis with multi-organ failure if left untreated.[14]

Diagnosis

This disease can be challenging to diagnose because the initial signs are non-descript and relatively common.[6] Analyzing recent travel history can be vital in the beginning stages of treatment. Serological assays are the best means of diagnosing this disease, with the indirect microimmunofluorescence assay (IFA) being considered the best tool. However, underlying illnesses, such as rheumatologic and other immune-mediated disorders, can lead to false positives.[14] To combat these limitations, a PCR test may also be used; this test looks for rickettsial DNA. It can sensitively detect the target DNA in a sample taken from an eschar or blood during the first few days of infection.[6]

Prevention

There is no vaccine available for this disease, so to prevent infection, the US CDC recommends taking personal safety measures when venturing out into areas known to harbour ticks.

Before going into these areas, the following preparations should be followed:

- Wear protective clothing that will cover your arms and legs, with closed-toed shoes. Wearing long socks that you can tuck your pants into will provide an extra layer of safety, especially if you are walking in areas with tall grass for an extended period of time.[15]

- Use strong insect repellent such as DEET on your body and Permethrin on your clothes[15]

- If you are taking a pet with you, they should also be updated on all preventative medications, and a veterinarian should be consulted for any extra precautions.[15]

After you return from these areas, the following precautions should be taken to prevent ticks from entering your home:

- Check clothes and gear used for any ticks. Dry clothes should be put into a dryer on high heat for 10 minutes to effectively kill any small ticks that may not be visible to the naked eye. If the clothes are wet, then they should be washed with hot water then dried on high heat.[15]

- Each individual should shower within two hours of returning home since this can help wash off any unattached ticks.[15]

- Finally, a full-body check should be performed to ensure that there is no attached tick.[15]

- If a pet was taken with you, they should receive a bath and a full-body tick check as well to ensure that they are not carrying anything into the home.[15]

Treatment

Early treatment for Queensland tick typhus is relatively simple. It includes a course of oral antibiotics such as doxycycline or chloramphenicol.[6] If a patient cannot take the medication orally, then the antibiotics are given intravenously by a medical professional.

Epidemiology

Queensland tick typhus is endemic to Australia.[16] Since there is no compulsory reporting of rickettsial infections in Australia, it can be difficult to monitor the geographical distribution of this disease and have an accurate count of the number of cases occurring each year.[17] The disease is most common along the east coast of Australia, coinciding with the geographic range of its tick vectors.[17]

History

This disease was noted during World War II among Australian soldiers undergoing basic training on the Atherton Tableland in Queensland.[18] It is most common along the east coast of Australia, including that of Queensland.[6]

References

- Spotted fevers, Department of Medical Entomology, University of Sydney

- "Queensland tick typhus". Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), (unattributed material, possibly unedited translation) - Stewart, Adam; Armstrong, Mark; Graves, Stephen; Hajkowicz, Krispin (2017-04-15). "Epidemiology and Characteristics of Rickettsia australis (Queensland Tick Typhus) Infection in Hospitalized Patients in North Brisbane, Australia". Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2 (2): 10. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed2020010. ISSN 2414-6366. PMC 6082070. PMID 30270868.

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1130. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- "MerckMedicus : Dorland's Medical Dictionary".

- Thomas, Stephen (June 2018). "Queensland tick typhus (Rickettsia australis) in a man after hiking in rural Queensland". Australian Journal of General Practice. 47 (6): 359–360. doi:10.31128/AJGP-10-17-4352. PMID 29966177. S2CID 49641323.

- "Medical Definition of Queensland tick typhus". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- Bechelli, Jeremy; Vergara, Leoncio; Smalley, Claire; Buzhdygan, Tetyana P.; Bender, Sean; Zhang, William; Liu, Yan; Popov, Vsevolod L.; Wang, Jin; Garg, Nisha; Hwang, Seungmin (2019). "Atg5 Supports Rickettsia australis Infection in Macrophages In Vitro and In Vivo". Infection and Immunity. 87 (1): e00651–18. doi:10.1128/IAI.00651-18. PMC 6300621. PMID 30297526.

- Mansourian, Erika (August 20, 2015). "The Life Cycle of the Tick from Eggs to Ambush". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- "Understanding The Tick Life Cycle". Mosquito Control | Mosquito Joe | Eliminate Mosquitos. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- "How ticks spread disease | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-09-21. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- "Tick-Borne Illnesses". Yale Medicine. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- "Rickettsial infections". www.health.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- Stewart, Adam; Armstrong, Mark; Graves, Stephen; Hajkowicz, Krispin (2017-07-12). "Rickettsia australis and Queensland Tick Typhus: A Rickettsial Spotted Fever Group Infection in Australia". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 97 (1): 24–29. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0915. ISSN 0002-9637. PMC 5508907. PMID 28719297.

- "Preventing tick bites on people | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-07-01. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- Wang, Jin-Mei; Hudson, Bernard J.; Watts, Matthew R.; Karagiannis, Tom; Fisher, Noel J.; Anderson, Catherine; Roffey, Paul (June 2009). "Diagnosis of Queensland Tick Typhus and African Tick Bite Fever by PCR of Lesion Swabs". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (6): 963–965. doi:10.3201/eid1506.080855. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2727311. PMID 19523304.

- Stewart, Adam; Armstrong, Mark; Graves, Stephen; Hajkowicz, Krispin (2017-07-12). "Rickettsia australis and Queensland Tick Typhus: A Rickettsial Spotted Fever Group Infection in Australia". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 97 (1): 24–29. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0915. ISSN 0002-9637. PMC 5508907. PMID 28719297.

- "Rickettsial Diseases of Military Importance: An Australian Perspective - JMVH". jmvh.org. Retrieved 2021-12-09.