Classical Anatolia

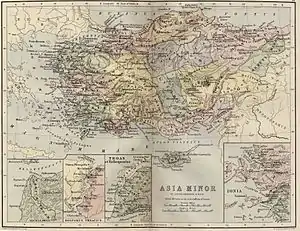

Classical Anatolia is Anatolia during Classical Antiquity. Early in that period, Anatolia was divided into several Iron Age kingdoms, most notably Lydia in the west, Phrygia in the center and Urartu in the east. Anatolia fell under Achaemenid Persian rule c. 550 BC. In the aftermath of the Greco-Persian Wars, all of Anatolia remained under Persian control except for the Aegean coast, which was incorporated in the Delian League in the 470s BC. Alexander the Great finally wrested control of the whole region from Persia in the 330s BC. After Alexander's death, his conquests were split amongst several of his trusted generals, but were under constant threat of invasion from both the Gauls and other powerful rulers in Pergamon, Pontus, and Egypt.

The Seleucid Empire, the largest of Alexander's territories, and which included Anatolia, became involved in a disastrous war with Rome culminating in the battles of Thermopylae and Magnesia. The resulting Treaty of Apamea in (188 BC) saw the Seleucids retreat from Anatolia. The Kingdom of Pergamum and the Republic of Rhodes, Rome's allies in the war, were granted the former Seleucid lands in Anatolia. Anatolia subsequently became contested between the neighboring rivalling Romans and the Parthian Empire, which frequently culminated in the Roman-Parthian Wars.

Anatolia came under Roman rule entirely following the Mithridatic Wars of 88–63 BC. Roman control of Anatolia was strengthened by a 'hands off' approach by Rome, allowing local control to govern effectively and providing military protection. In the early 4th century, Constantine the Great established a new administrative centre at Constantinople, and by the end of the 4th century a new eastern empire was established with Constantinople as its capital, referred to by historians as the Byzantine Empire from the original name, Byzantium.

In the subsequent centuries up to including the advent of the Early Middle Ages, the Parthians were succeeded by the Sassanid Persians, who would continue the centuries long rivalry between Rome and Persia, which again culminated in frequent wars on the eastern fringes of Anatolia. Byzantine Anatolia came under pressure of the Muslim invasion in the southeast, but most of Anatolia remained under Byzantine control until the Turkish invasion of the 11th century.

Early antiquity

Lydia had become the predominant power in western Anatolia by the 7th century BC, although often subject to Assyrian control. The Lydian empire gained independence from Assyria by the end of the 7th century. The flourishing of Lydia during the first half of the 6th century BC is also dubbed the Lydian Empire period. Although the Iranian peoples had existed in the area south of the Caspian Sea (Iranian Plateau) from pre-historic times, their major influence began when the Medes united them in 625 BC allowing them to sweep away the Assyrian Empire shortly after, when Cyaxares (625–585 BC) led the invasion in 612 BC. Lydian king Sadyattes (ruled c. 624/1–610/609 BC) joined forces with Cyaxares the Mede to drive the Cimmerians out of Anatolia. This alliance was short lived, since his successor Alyattes (ruled c. 605–560 BC) found himself being attacked by Cyaxares, although the neighbouring king of Cilicia intervened, negotiating a peace in 585 BC, whereby the Halys River in north central Anatolia was established as the Medes' frontier with Lydia. Herodotus writes:

- "On the refusal of Alyattes to give up his supplicants when Cyaxares sent to demand them of him, war broke out between the Lydians and the Medes, and continued for five years, with various success. In the course of it the Medes gained many victories over the Lydians, and the Lydians also gained many victories over the Medes."

Alyattes issued minted electrum coins, and his successor Croesus, ruling c. 560–546 BC, became known for being the first to issue gold coins.

The southeast of Anatolia was ruled by the Assyrian Empire. Tabal was a Luwian speaking Neo-Hittite kingdom of South Central Anatolia which fell under Assyrian rule in 713 BC.

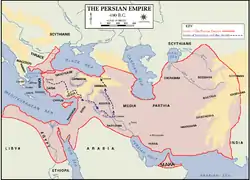

Persian rule

The Medean Empire turned out to be short lived (c. 625 – 549 BC). By 550 BC, the Median Empire of eastern Anatolia, which had existed for barely a hundred years, was suddenly torn apart by a Persian rebellion in 553 BC under Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great c. 600 BC or 576–530 BC), overthrowing his grandfather Astyages (585–550 BC) in 550 BC. The Medes then became subject to the Persians.

The Persians, who had scant resources for governing their vast empire, ruled relatively benignly as conquerors, attempting to obtain the cooperation of the local elite in governance. They ruled their vassal states by appointing local rulers, or satraps with responsibility for their satrapies (Greek: Satrapeia). However, the Greeks referred to these satraps as 'tyrants', meaning they were neither democratically elected or derived authority from dynasty. The Achaemenid Persian Empire, continued its expansion under Darius the Great (521–486 BC). The satrap system of local governors continued to be used and upgraded and other governmental upgrades were carried out.[1][2]

Anatolia was carved up under Persian hegemony into regional administrations (Satrapies or provinces, depending on sources) which replaced the hegemonic kingdoms prior to the conquest. Kings were replaced by Satraps. Satrap and Satrapy corresponding to Governor and Province respectively. The administration was hierarchical, often referred to as Great, Main and Minor Satrapies. The main administrative units in Anatolia were the Great Satrapy of Sardis (Sparda/Lydia) in the west, Main satrapy of Cappadocia centrally, Main Satrapy of Armenia in the north-east and Main Satrapy of Assyria in the south-east. These correspond to Herodotus's Districts I-IV. However, the number of satrapies and their boundaries varied over time.

Within the hierarchical system, Sparda was a Great Satrapy consisting of the Major Satrapies of Sarda (including minor satrapies of Hellespontine Phrygia, Greater Phrygia, Caria, and Thracia) and Cappadocia. Note that Ionia and Aeolis were not considered separate entities by the Persians, while Lycia was included in semi-autonomous Caria, and Sparda included the offshore islands. Greater Phrygia included Lycaonia, Pisidia, and Pamphylia. Cappadocia initially included Cilicia, also known as Cappadocia-beside-the-Taurus, and Paphlagonia.

Assyria was a Main Satrapy of the Great Satrapy of Babylon, and included Cilicia, while Armenia was a Main Satrapy within the Great Satrapy of Media.[3]

Anatolia remained one of the most principal regions of the empire during its entire existence. During the reign of Darius the Great, the Royal Road, which directly linked the city of Susa with the western Anatolian city of Sardis.

The fall of Lydia (546 BC) and the Lydian revolt

By 550 BC Lydia controlled the Greek coastal cities, who paid tribute, and most of Anatolia, except Lycia, Cilicia and Cappadocia. In 547 BC, King Croesus, who had amassed great wealth and military power, but concerned by the growing Persian power and obvious intent, took advantage of the instability of the Persian revolt and besieged and captured the Persian city of Pteria in Cappadocia.[1][2] Cyrus The Great then marched with his army against the Lydians. Although the Battle of Pteria led to a stalemate, the Lydians were forced to retreat to their capital city of Sardis. Some months later the Persian and Lydian kings met at the Battle of Thymbra. Cyrus won, capturing Sardis after a 14-day siege, Croesus giving himself up to Cyrus. According to the Greek author Herodotus, Cyrus treated Croesus well and with respect after the battle, but this is contradicted by the Nabonidus Chronicle, one of the Babylonian Chronicles (although whether or not the text refers to Lydia's king or prince is unclear).[4]

Lydia then became the Persian Satrapy of Sardis, also known as the Satrapy of Lydia and Ionia, although there was an unsuccessful rebellion led by Pactyas (Pactyes), the leader of the civil administration, against Tabalus, the Persian military commander (satrap) (546–545 BC), shortly thereafter. Once Lydia had been subdued, Cyrus returned to deal with problems in the East leaving a garrison to assist in the governing of his new acquisition. Almost immediately Pactyas, who had been given the responsibility of raising tributes, raised a mercenary army from neighboring Greek cities and besieged Tabulus in the citadel. Herodotus' account that Cyrus intended to enslave the Lydians seems unsubstantiated. Pactyas soon found that he had no allies and furthermore that Cyrus was acting swiftly to put down the rebellion, sending Mazares (545–544 BC), one of his generals to restore order. Pactyas subsequently fled to the coast and took refuge in the Aeolian city of Cyme. Mazares demanded that Cyme release Pactyas to him. Fearing retribution, the Cymeans sent him to Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. On hearing that the Mytilenians were negotiating a price for Pactyas, the destination was changed to Chios, but they too handed him over to the Persians.[2][5]

Mazares was followed by Harpagus (544–530 BC) on his death, and then Oroetus (530–520 BC). Oroetus became the first satrap recorded as demonstrating insubordination with respect to the central power of Persia. When Cambyses (530–522 BC), who succeeded his father Cyrus, died, the Persian Empire was in chaos prior to Darius the Great (522–486 BC) finally securing control. Oroetus defied Darius' orders to assist him, whereupon Bagaeus (520–517 BC) was sent by Darius to arrange his murder.

The subjugation of Ionia and the Ionian Revolt (500–493 BC)

Cyrus had initially unsuccessfully tried to persuade the Aeolian and Ionian cities to rebel against Lydia. At the time of the fall of Sardis, only one city, Miletus, had made terms with Cyrus. According to Herodotus, when Lydia fell to Cyrus, the Greek cities begged him to allow them to exist within the former Lydian territories on similar terms to those they had earlier enjoyed, Cyrus pointed out that they were too late, and they started building defensive structures. They appealed to Sparta for help, but Sparta refused, instead warning Cyrus not to threaten the Greeks. Cyrus was unimpressed, but nevertheless headed east without bothering them further. This account seems somewhat conjectural.[2][5]

Following the defeat of the Lydian revolt, Mazares began to reduce the other cities in the Lydian lands one by one, starting with Priene and Magnesia. However, Mazares died, and was replaced by another Mede, Harpagus (544–530 BC), who completed the subduing of Asia Minor. Some communities, rather than face a siege, chose exile, including Phocaea to Corsica and Teos to Abdera in Thrace. Although our principal source for this period, Herodotus of Halicarnassus, implies this was a swift process, it is more likely that it took four years to subdue the region completely, and the Ionian colonies on the coastal islands remained largely untouched.[2][4]

According to Herodotus (Histories V, VI) around 500 BC Aristagoras, tyrant of Miletus approached Artaphernes, satrap of Lydia (c. 492 – 480), for assistance in aiding some citizens of Naxos who had been forced to flee (C. 502 BC) and seek his help. He planned to annex not only Naxos but also the Cyclades and Euboea. With the permission of Darius he gathered a force to invade Naxos, but the expedition was a failure. Motivated by fear of the wrath of Darius he prevailed upon those in the expedition to mount an insurrection and subsequently went to Sparta (unsuccessfully) and Athens (successfully) for help. The Ionians attacked Sardis in approximately 499 BC, but Artarphernes managed to hold the acropolis, although the lower city was burnt. The Ionians retreated but were defeated by pursuing Persians at Ephesus in 498 BC, whereupon the Athenian ships withdrew. However, over the next two years open rebellion broke out from Byzantium to Caria and Cyprus. Eventually Aristagoras realized the futility of the exercise, as Artaphernes won a number of victories, and fled. Miletus fell to the Persian forces in 494 BC, following the Battle of Lade, who wreaked vengeance. The last pockets of resistance were obliterated by 493 BC. Herodotus depicts these events as the catalyst to the Graeco-Persian Wars (499–449 BC).[2][6]

However, Herodotus, as is so often our only source, had an agenda in his imprecise accounts, which do not fit well with what is known of the period. It is likely that the affair in Naxos represented a democratic revolt against the tyrants.[2]

Hellespontine Phrygia

Hellespontine Phrygia lay to the north of the Lydia/Sardis satrapy, incorporating Troad, semi-autonomous Mysia, and Bithynia with its capital at Dascylium (modern day Ergili) on the south of the Hellespont. Previously it was part of the Kingdom of Lydia. Mitrobates was a satrap, and one of the officials killed by Oroetes (Oroetus), satrap of Sparda (Sardis), in the 520s. Because of its strategic position between Europe and Asia it was the launching pad for expeditions to subdue Thrace and Macedonia. Arsites was the last Achaemenid satrap of Dascylium (350–334 BC) according to Demosthenes, committing suicide after the Persian defeat at the battle of Granicus in 334 BC at the hands of Alexander the Great.[3]

Greater Phrygia

Greater Phrygia was a minor satrapy of Sparda, with its capital at Celaenae. It concluded Lycaonia, Pisidia, and Pamphylia.

Cilicia

Cilicia remained a semi-independent minor satrapy under both Croesus of Lydia, and under Persian rule, although paying tribute. Similarly Lycia remained under petty local dynasts, with allegiance to Persia.

Mysia

Mysia was ruled by its own dynasty within the minor satrapy of Hellespontine Phrygia.

Caria

.jpg.webp)

Caria was a satrap of the Persian Empire which included Lycia as well as the islands of Chios, Rhodes, and Cos at times. The appointed local ruler Hecatomnus took advantage of his position. He gained for his family an autonomous hand in control of the province by providing the Persians with regular tribute, avoiding the look of deception. His son Mausolus continued in this manner, and expanded upon the groundwork laid by his father. He first removed the official capital of the satrap from Mylasa to Halicarnassus, gaining a strategic naval advantage as the new capital was on the ocean. On this land he built a strong fortress and built up a strong navy. He shrewdly used this power to guarantee protection for the citizens of Chios, Kos, and Rhodes as they proclaimed independence from Athenian Greece. Mausolus did not live to see his plans realized fully, and his position went to his widow Artemisia. The local control over Caria remained in Hecatomnus's family for another 20 years before the arrival of Alexander the Great.[2][3][8]

Greco-Persian Wars 499–449 BC

The preceding events of the Ionian Revolt marked the beginning of half a century of conflict between the superpowers that faced each other across the Aegean. The Persians were already in Europe, with a presence in both Thrace and Macedonia, a position they consolidated following the suppression of the revolt between 492 and 486 BC under Mardonius and later by Darius the Great.

From the Greek perspective the first war was when Darius assembled a fleet in Cilicia and Samos under Datis and Artaphernes (son of the satrap Artaphernes) and sailed for Eritrea in 490 BC, first taking islands such as Naxos which it had failed to capture in 500, in addition to disembarking at Marathon where they were soundly defeated. Greek (Herodotus) and Persian sources (for instance see Dio Chrysostom XI 148) differ in terms of the significance of Marathon, great victory or minor skirmish.

Greece was spared further invasions when an unplanned interbellum (490–480 BC) occurred due to an insurrection in Egypt in 486 BC and Darius' illness and death that year. By 480 BC, Darius' successor, his son Xerxes I (485–465 BC) had amassed a huge army, and marched into Europe by crossing the Hellespont by means of pontoon bridges, meeting and defeating the Greeks at the Battle of Thermopylae later that year and razing Athens. However, the loss of the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis gave command of the sea to the Greeks, and Xerxes retreated back to Asia. The following year (479 BC) the Greeks won a decisive land victory at Platea in which Mardonius was also killed, followed by another naval victory at Mycale. Greece then went on the offensive, capturing Byzantium and Sestos and thus controlling the Hellespont.[2]

Following these Persian reverses, the Greek cities of Asia Minor again rebelled. The focus of the war now moved to the Aegean islands with the formation of the Delian League in 477 BC. Over the next 30 years Greek forces continued to harass Persian garrisons, invading Asia Minor in the 460s with an important victory at the Battle of the Eurymedon c. 469. The wars effectively ended in 449 BC with the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus, a peace being declared, which Diodorus refers to as the Peace of Callias, although this is debated.

Skirmishes continued, and the Greek cities of Asia Minor continued to be pawns in the struggles.

Final years: the invasion of the Macedonians 358–330 BC

The later years of the Empire were beset by internal turmoil. Artaxerxes III (358–338 BC) achieved the throne by violent means and was rumored to have been murdered himself. His successor Artaxerxes IV Arses (338–336 BC) also met a violent end, paving the way for the accession of his nephew Darius III (336–330), then Satrap of Armenia. Darius proved to be the last king to rule since in the same year Alexander the Great became king of neighboring Macedon. Within a year Alexander was in Thrace, putting down rebellions and securing his northern frontiers. Alexander then turned his attention to the east, landing on the shores of Anatolia near Sestos on the Gallipoli peninsula in 334 BC, and soon crossing the Hellespont into Asia (335 BC). Initially the Persians offered little resistance and Alexander began to liberate Greek city states.

Advancing on Dascylium he first encountered Persian troops at the Battle of Granicus in 334 BC. This battle occurred on the Granicus (Biga Çayı) river near modern-day Biga in Çanakkale, on the south coast of the Sea of Marmara. The Persians were routed and the Greeks moved down the Aegean coast, taking Sardis, and besieging many cities. From the Aegean they moved east along the Mediterranean coast as far as Side in Pamphylia (333 BC), securing all of the Anatolian naval bases. From Side they moved north into the interior of Phrygia and Cappadocia before returning through the Cilician Gates to the Cilician coast, and then east towards the Gulf of Issus. It was there they encountered and defeated Darius at the Battle of Issus (333 BC).

On reaching Mount Amanus, scouts found the Persians advancing through the plains of Issus. Realizing that the terrain at this point favored his smaller army, Alexander attacked the Persians, who were effectively squeezed by the Macedonians. Although Darius escaped, back across the Euphrates river, leaving the rest of his family in Alexander's hands, the battle marked the end of Persian hegemony in Anatolia. Alexander then turned his attention to Syria, the eastern Mediterranean coast and Egypt.[8]

Darius himself was murdered in 330 BC, and shortly afterwards Alexander routed the remaining Persian forces at the Battle of the Persian Gate and the Achaemenid Empire was over.

Hellenistic period

Alexander the Great

Alexander (336–323 BC) succeeded his father King Philip of Macedon (359 BC – 336 BC) on his assassination in 336 BC. Alexander invaded Asia Minor in 335 BC with a combined land and naval force, and by 333 BC had effectively vanquished the Persians in the Anatolian lands, and ending the Achaemenid Empire by 330 BC. However, he devoted the rest of his life to military conquests further east, dying in 323 BC. Thus he fulfilled his father's ambition of liberating the Greeks of Asia Minor.

Administratively he continued the satrapy system, his strategy being to respect and win support from the conquered (or liberated) people's, respecting their traditions. he also positioned himself as a crusader for pan-hellenism, rescuing the Greek people of Anatolia from tyrants and oligarchs. In addition he colonised the lands he captured with Greek settlers, spreading Greek culture. One of the controversies is the extent to which the Macedonian Empire represented either rupture or continuity. The ascendancy of Greek, and by extension European culture in an area predominantly influenced by Asia to date was to leave a lasting legacy.[9][10]

Wars of the Diadochi and division of Alexander's empire

In June 323 BC, Alexander died suddenly and unexpectedly in Babylon at the age of 32, leaving a power vacuum in Macedon, putting all he had worked for at risk. His vision of a unified empire proved short lived. He had no heir, and had not made apparent plans for succession. Some classical writers state he wished Perdiccas one of his generals, to take charge, and that Perdiccas envisioned sharing power, as regent, with his then unborn son, Alexander IV (323–309 BC). This was not universally accepted, and his half-brother Arrhidaeus (323–317 BC) was advanced as a candidate by Meleager. Eventually Alexander and Philip were made joint monarchs and responsibility for regional administration divided up at the Partition of Babylon (323 BC).[11] Philip was unable to rule effectively due to a serious disability, and both he and Alexander were soon murdered. Perdiccas himself was assassinated in 321 BC.[11][12]

Power often lay with the Satraps, usually generals. In Anatolia, this initial division of power at Babylon was as follows;

Western Anatolia: Hellespontine Phrygia by Leonnatus, Lydia by Menander, Caria by Asander

Central Anatolia: Phrygia, Lycia and Pamphylia by Antigonus, Cappadocia and Paphlagonia by Eumenes of Cardia, Cilicia by Philotas

Eastern Anatolia: Armenia by Neoptolemus

However, dissent was endemic, and almost continuous war ensued amongst the Macedonian generals, lasting over 40 years; these wars were referred to as the wars of the successors (Διάδοχοι, Diadokhoi, or Diadochi) (323–276 BC). Although Cappadocia had been allocated to Eumenes, it had not yet been subdued and had to be put down in 322 BC, in the course of which Antigonus fell out with Perdiccas and fled to Europe from Phrygia, where he initiated a conspiracy (First War of the Diadochi). Perdiccas' murder necessitated a further partitioning and appointment of a new regent, Antipater, at Triparadisus in 321 BC. Eumenes was condemned and control of Cappadocia passed to Nicanor, while Lydia was given to Cleitus and Hellespontine Phrygia to Arrhidaeus.

The second partitioning did little to quell the continuing scheming and jockeying for power. Antipater's illness in 320 BC led him to appoint Polyperchon as regent, passing over his own son Cassander, who now conspired with Antigonus. The result was civil war (Second War of the Diadochi) with Cassander declaring himself regent in 317 BC and King in 305 BC, having had Alexander IV murdered in 309 BC.

Meanwhile, Antigonus in Phrygia was expanding east forcing Seleucus, Satrap of Babylon, to flee to Ptolemy, Satrap of Egypt and Libya in 315 BC (Third War of the Diadochi). This aggression brought pressure to bear on Antigonus, who soon found himself under attack in Thrace, Caria and Palestine. As a result, Seleucus was reinstated in 312 BC, and a treaty was arranged in 311 BC between Cassander, Lysimachus Satrap of Thrace, Antigonus, Seleucus and Ptolemy which divided the Empire into four spheres of influence. By 304 BC all of these had proclaimed themselves 'kings' (Basileus: Βασιλεύς), effectively ending the concept of a Macedonian Empire, although it was unclear as to whether all saw themselves as the legitimate heir of the entire empire. It was Antigonus and his son Demetrius who continued to wage war (Fourth War of the Diadochi). The Fourth War culminated in the Battle of Ipsus, Phrygia in 301 BC, in which Antigonus now in his 80s faced the combined forces of Cassander, Lysimachus and Seleucus. Antigonus was killed, and Demetrius fled, allowing his enemies to carry out a third partition, dividing his possessions between them.

In post-Ipsus Anatolia, Lysimachus held the west and north, Seleucus the east, and Ptolemy the south east. For a while Pleistarchus, Antipater's son and Cassander's brother ruled Cilicia, before being driven out the following year (300 BC) by Demetrius. The other exception was Pontus which under Mithridates I managed to gain independence.

The third partition of 301 BC was no more effective at bringing stability to the region than its predecessors. Demetrius, who eventually became King of Macedon (294 BC – 288 BC), was still at large controlling a significant naval force, raiding Lysimachus' territory in Asia Minor. Nor did the Ipsus alliance between the three kings last.

Lysimachian Empire 301–281 BC

Of the three empires carved out of Alexander's possessions following the battle of Ipsus, the Lysimachian of Thrace, Western (including Lydia, Ionia, Phrygia) and Northern Asia Minor, was the shortest lived. Lysimachus attempted unsuccessfully to extend his possessions in Europe and Greece. Some of Lysimachus' cruelty, such as the murder of his son Agathocles in 284 BC engendered both revulsion and revolt. Distrusting Seleucus, Lysimachus had now allied himself with Ptolemy. Seleucus invaded the Lysimachian lands and in the ensuing Battle of Corupedium, near Sardis in 281 BC, Lysimachus was killed and Seleucus seized control over western Asia Minor.[11][13]

Ptolemaic Empire 301–30 BC

Of all the major satraps appointed on the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC), Ptolemy (323–283 BC) settled into his new province of Egypt and Libya with the least difficulty, controlling much of the Levant and at times south-eastern Anatolia. This was confirmed following the third partition following the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. However, a series of Syrian Wars (274–168 BC) between the Ptolomies and the Seleucids varied the degree of control they had in Anatolia. The First Syrian War (274–271 BC) fought by Ptolemy I's son and successor Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 BC) resulted in extending these possessions to include Caria, Lycia, Cilicia, and Pamphylia, as well as the Aegean islands, only to lose some of them in the second war (260–253 BC). The territorial extent of the Ptolemies reached its zenith under Ptolemy III Euergetes (246–222 BC) and the third (Laodicean) war (246–241 BC).

Thereafter the Ptolemaic powers declined. Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC) seized territory in Caria, and Roman influence steadily increased as it progressively absorbed much of the Greek world. Egypt formed a pact with Rome and the dynasty eventually came to an end in 30 BC with the death of Cleopatra VII (51–30 BC).

Seleucid Empire 301–64 BC

On the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC Seleucus (321–281 BC) was appointed to head the elite cavalry (ἑταῖροι, hetairoi) and a Chiliarch. At the Partition of Triparadisus in 321 BC he was appointed Satrap of Babylonia, but soon found himself involved in the Wars of the Diadochi. In particular this involved conflict with Antigonus, Satrap of Phrygia, to his west, who progressively enlarged his possessions to include all of Asia Minor. Eventually, at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC Antigonus was overthrown and killed, and his lands partitioned. This gave Seleucus control of south eastern Anatolia. In the ensuing years he was in conflict with Demetrius, Antigonus' son gaining and then losing Ciliciain 294 and 286 BC respectively, but then regained it shortly thereafter. His next problem was to deal with Lysimachus who now controlled Thrace and western Asia Minor. In the ensuing Battle of Corupedium, near Sardis in 281 BC, Lysimachus was killed and Seleucus seized control over the remaining lands of Asia Minor. Now reigning over all of Alexander's empire except the Ptolemaic lands in Egypt, his victory was short lived. Immediately moving to take commands of the new lands in Europe, Thrace and Macedonia he crossed into Thracian Chersonese when he was assassinated near Lysimachia by Ptolemy Keraunos, future king of Macedon. Seleucus was noted for his founding of cities, such as Antioch (one of many cities with that name), named after his father Antiochus, and which became the capital of Syria.[13]

After the death of Seleucus, the vast and unwieldy empire he left faced many trials, both from internal and external forces. His son Antiochus I Soter (281–261 BC) faced the first of many Syrian Wars with the Seleucids southern neighbours, the Ptolomies. He was unable to fulfill his father's ambitions of incorporating Thrace and Macedonia and nor was he able to subdue Cappadocia and Bithynia in Asia Minor. A new threat was incursions by the Gauls from the north west but they were repelled in 278 BC. Within Asia Minor, the power of Pergamon on the Aegean coast, a remnant of the Lysimachean Empire, was growing. Eumenes I, dynast of Pergamon, revolted against Seleucid rule and defeated Antiochus near Sardis in 262 BC, guaranteeing Pergamon's independence. Antiochus died the following year,[14]

Antiochus I Soter was succeeded by his son Antiochus II (261–246 BC) named Theos, or "divine", who conducted the Second Syrian War (260–253 BC). Eventually he was poisoned by his first wife, Laodice I who also poisoned his second wife Berenice Phernophorus, daughter of Ptolemy II Philadelphus and her infant son. Antiochus II's son by Laodice from his first wife, Seleucus II Callinicus (246–225 BC), was proclaimed by his mother.

Seleucus II oversaw the Third Syrian War (246–241 BC) with Berenice's brother, Ptolemy III Euergetes. In Asia Minor a rebellion by his younger brother Antiochus Hierax led to Seleucus II leaving the lands beyond the Taurus Mountains to him following a defeat at Ancyra in 236 BC, although the latter was eventually driven out of Anatolia by Pergamon in 227 BC.[15] Seleucus' sister Laodice married Mithridates II in 245 BC and brought with her the lands of Phrygia as a dowry.[16] Despite this Mithridates joined Antiochus Hierax against Seleucus.

After the brief reign of Seleucus II's son Seleucus III Ceraunus ( 226–223 BC), his brother Antiochus III the Great (223–187 BC) ascended the throne. By the time Antiochus III became king, the empire had already reached a low point. In the east provinces were breaking away, while in Asia Minor, subject states were becoming increasingly independent, including Bithynia, Pontus, Pergamum and Cappadocia (traditionally difficult to subjugate). A new presence was Galatia, a 3rd-century settlement of Gauls from Thrace in central Anatolia. Antiochus III set about restoring the former glories of the empire, initially campaigning in the east and subduing the independent provinces, before turning his attention to the west. His ambition to fulfill the thwarted dreams of his great great grandfather Seleucus I proved to be his undoing. His initial attempts to regain control of Asia Minor drew the attention of the growing Mediterranean power of Rome when Smyrna appealed to it for help. He then crossed into Europe in 196 BC and Greece in 192 BC but by 191 BC came up against the Roman legions at the Battle of Thermopylae where his defeat forced his retreat from Greece. The following year the Romans pursued him into Anatolia inflicting another major victory at the Battle of Magnesia in Lydia. Antiochus was forced to sue for peace and by the terms of the Treaty of Apamea in 188 BC retreated beyond the Taurus Mountains, dying the following year. Anatolia now lay largely in the hands of the Romans and their allies, at least in the west. Those states that had allied themselves with the Romans were freed while Caria south of the River Maeander and Lycia were granted to Rhodes. The balance of Antiochus' lands, the largest share, were granted to Eumenes II of Pergamum. These settlements were made on the understanding that they would all keep the peace in a manner satisfactory to Rome.[17]

While the Seleucids continued to maintain lands in south eastern Anatolia the empire was progressively weakened on all fronts, and became progressively unstable, torn by civil war in the 2nd century BC. After the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes (138–129) BC the empire became increasingly diminished and by the reign of Antiochus IX Cyzicenus (116–96 BC) there was little left outside Antioch and Syria. The invasion of Syria by Tigranes the Great of Armenia (95–55 BC) in 83 BC virtually extinguished the empire, a process completed when Pompey made Syria a Roman Province in 64 BC.

Pontus 291–63 BC

The Kingdom of Pontus lay on the north west Black Sea coast, stretching from Paphlagonia to Colchis and bordered to the south by Cappadocia. Its mountain ranges were divided by river valleys including the Halys, Iris, and Lycus, parallel to the coast. Its main centres were on the Lycus and Iris rivers including the royal centre of Amaseia.

Pontus was founded by Mithridates I (302 – 266 BC) in 291 BC, who assumed the title of king in 281 BC. Its capital was Sinope, now the Turkish town of Sinop. Originally he had inherited Cius to the west in Bithynia, but fled from Antigonus Monophthalmos to form a new dynasty in nearby Paphlagonia. Appian states that he was directly descended from the Persian Satrap of Pontus. he consolidated his kingdom seeking alliances from neighbouring peoples, including the Gauls, as protection form the larger powers of the region.

His grandson, Mithridates II (c. 250–210 BC) married into the Seleucid line, acquiring Phrygia as a dowry from Laodice, sister of Seleucus II. Later he was part of an alliance that defeated Seleucus at Ancyra in 239 BC. However, the alliance between the dynasties was further consolidated when he gave his daughter, Laodice III in marriage to Antiochus III, and another daughter to Antiochus'cousin, Achaeus.

Mithridates II's grandson, Pharnaces I (c. 190 – c. 155 BC) waged war on many of his neighbours including Eumenes II of Pergamon and Ariarathes IV of Cappadocia (220 BC – 163 BC) as well as Galatia in 181 BC. Ultimately he gained little, although the Romans attempted to intercede. He also continued alliances with the Seleucids, marrying Nysa who was the daughter of his cousins Laodice IV and crown prince Antiochus. He was succeeded by his brother Mithridates IV (c. 155 – c. 150 BC) who allied himself with Rome and her allies, including Pergamon.

Mithridates IV was succeeded by his nephew, Mithridates V (c. 150 – 120 BC), son of Pharnaces I. He assisted the Romans in suppressing the revolt by the pretender of Pergamon, Eumenes III. In exchange he received Phrygia from the Romans. He allied himself with Cappadocia by marrying his daughter Laodice to Ariarathes VI of Cappadocia.

His son, Mithridates VI (120 – 63 BC) reversed earlier policies of friendship with the growing power of Rome, engaging in a series of wars that now bear his name, the Mithradatic wars (88–63 BC), and which ultimately led to the end of his kingdom and dynasty. Mithridates was ambitious and planned to conquer the litoral of the Black Sea. His first campaign was against Colchis on the eastern shore of the Black Sea, and then extended as far north as Crimea.

Mithridatic wars 88–63 BC

He next turned his attention to Anatolia where he sought to partition Paphlagonia and Galatia with King Nicomedes III of Bithynia (127 – 94 BC) in 108 BC also acquiring Galatia and Armenia Minor but soon fell out with him over control of Cappadocia and by extension his ally Rome setting the scene for the subsequent series of Mithridatic Wars (88–63 BC). Relations between the adjacent states of Pontus, Bithynia, Cappadocia and Armenia were complex. Mithridates' sister, Laodice was queen of Cappadocia, being married to Ariarathes VI (130 – 116 BC). Mithridates had his brother in law Ariarathes murdered, whereupon Laodice married Nicomedes III of Bithynia. Pontus and Bithynia then went to war over Cappadocia, and Mithridates had his nephew and new king, Ariarathes VII (116 – 101 BC) killed. Ariarethes' brother Ariarathes VIII (101 – 96 BC) ruled for a brief period before being replaced by Mithridates with his own son Ariarathes IX (101 – 96 BC). The Roman Senate then had Ariarathes replaced by Ariobarzanes I (95 – c. 63 BC). Mithrodates then dragged his eastern neighbour Armenia into the fray, since Tigranes the Great (95–55 BC) was his son in law.

Nicomedes IV of Bithynia (94 – 74 BC) declared war on Pontus aided by Roman legions in 89 BC launching the First Mithridatic War (89–84 BC). During this period, Mithridates swept through Asia Minor occupying most of it except Cilicia by 88 BC, before Roman retaliation forced his retreat and abandonment of all the occupied territory. Mithridates still controlled his own Pontine lands and a second war by Rome (83–81 BC) was rather inconclusive and failed to dislodge him. In the meantime the Roman presence in Anatolia was steadily growing. As with Pergamon Nicomedes who had no heirs, bequeathed Bithynia to Rome. This provided the opportunity for Mithridates to invade Bithynia and precipitated the Third Mithridatic War (74–63 BC). Mithridates' position was considerably weakened following the fall of Armenia to Rome in 66 BC. Pompey had dislodged Mithridates from Pontus by 65 BC, who now retreated to his northern domains but was defeated by rebellion in his own family and died, possibly by suicide, ending the Pontine Kingdom as it then existed.

Aftermath

The lands were divided with the western part including the capital being absorbed into the Roman province of Bithynia et Pontus, while the east was divided into client kingdoms including Pontus, with Mithridates' son Pharnaces II (63–47 BC) as king. However, he attempted to take advantage of the Roman civil war between Caesar and Pompey (49–45 BC) but was driven back by Caesar at Zela in 47 BC. Many of the centres brought into the Roman province reverted under Mark Anthony, but were eventually returned to the provincial fold, forming part of the province of Galatia as the districts of Pontus Galaticus and Pontus Polemoniacus.[18] Pontus continued under client kings, initially descended from Pharnaces. Polemon I ruled from 38 to 8 BC, followed by his widow Pythodorida (8 BC – 38 AD), and after her death her son Polemon II (38–62 AD). Pythidora joined her kingdom to Cappadocia by marrying Archelaus until his he was deposed in 17 BC by the Emperor Nero (54–68 AD), while Polemon II was also king of Cilicia where he continued as king after losing Pontus which then also became a Roman province.

Bithynia 326–74 BC

Bithynia was an area in north west Anatolia, south of the Sea of Marmara. It was originally just part of the Chalcedon peninsula but was extended to include Nicaea and Prusa and the cities of the coast, east towards Heraclea and Paphlagonia, and south across the Propontis to Mysian Olympus.

Bithynians were of Thracian origin. There is some evidence that even before the invasion of Alexander the Great, Bithynia enjoyed some independence.[18] After Alexander's death, Zipoetes I (326–278 BC) had himself proclaimed king in 297 BC, waging war against both Lysimachus and the Seleucids. Zipoetes was succeeded by his son Nicomedes I (278 – 255 BC) who was instrumental in inviting aid from the Gauls, who having entered Anatolia settled in Galatia were to prove a source of problems in Bithynian affairs. Like the other Anatolian states Bithynia was torn by disputes within the ruling family and civil war. They formed various judicious alliances and marriages against the Seleucids and Heraclea and were often at war with neighbouring states.

Prusias II (156–154 BC) joined Pergamon in a war against Pharnaces I of Pontus (181–179 BC) but then attacked Pergamon (156–154 BC) with disastrous consequences. His son Nicomedes II (149 – 127 BC) sided with Rome in putting down the revolt by Eumenes III (133–129 BC), the pretender of Pergamon. His son Nicomedes III (127 – 94 BC) became entangled in the complex intermarriages of Pontus and Cappadocia, attempted to annex Paphlagonia and claim Cappadocia. He was succeeded by his son Nicomedes IV (94 – 74 BC) who bequeathed the kingdom to Rome, precipitating the Mithridatic Wars between Rome and Pontus who claimed Bithynia.

Galatia 276–64 BC

Galatia was an area in central Anatolia, situated in northern and eastern Phrygia and Cappadocia, east and west of Ancyra (Ankara). It was settled by Gauls who were originally invited to Anatolia by Nicomedes I of Bithynia around 278 BC to aid his campaigns but remained and settled in an adjacent area over the next decade, with Ancyra as its capital city. They frequently raided surrounding lands and were hired as mercenaries in the continuing struggles between the Anatolian states. They were defeated by Attalus I of Pergamon c. 230 BC. Subsequently, the theme of the Dying Gaul, a statue displayed in Pergamon, was a favorite in Hellenistic art. Rome launched a campaign against them in 189 BC, defeating them in the Galatian War. At times part of Pontus, they became independent again in the Mithridatic Wars. They controlled territory from the Pamphylian coast to Trapezus.

The Gauls retained traditional Celtic models of governance with tribes and cantons, whose rulers were described by the Greeks as Tetrachs. The territory was divided between three tribes, the Tolistobogii in the west, the Tectosages around Ancyra, and the Trocmi in the east around Tavium. Of these we know more about Deiotarus (c. 105 – 42 BC) than many others. As chief tetrach of the Tolistobogii he was eventually granted the title of King of Galatia by Pompey, having allied himself with Rome against Pontus in the Mithridatic Wars. The title came with part of the Pontic lands, specifically Lesser Armenia in the east. Deiotarus was adroit at manoeuvering between the various internal struggles of the Roman Republic surviving to an advanced age. He formed a political alliance with Pergamon by marrying Berenice, daughter of Attalus III (138–133 BC) the last king of Pergamon.

In 64 BC Galatia became a client state of Rome and a Roman province in 25 BC following the reign of Amyntas (36–25 BC).[18]

Pergamon 281–133 BC

Pergamon an Ionian city state close to the Aegean coast, in Mysia was a remnant of the Lysimachean Empire, which was destroyed in 281 BC. Today it is at the modern town of Bergama. The site formed a natural fortress of strategic importance, guarding the Caïcus plains. Capital of the Attalid dynasty, it was one of the three major cities of Asia Minor.[18]

Philetaerus who had served under Lysimachus was the ruler of Pergamon, Lysimachus' treasury, at that time, exercised some autonomy under the Seleucids who seized Lysimachus' lands, ruling from 282–263 BC. The subsequent dynasty was named Attalid, in honour of Philetaerus'father Attalis. On his death he was succeeded by his nephew Eumenes I (263–241 BC), who revolted against Seleucid rule and defeated Antiochus near Sardis in 262 BC, guaranteeing Pergamon's independence. Eumenes enlarged Pergamon to include parts of Mysia and Aeolis, and held tightly onto the ports of Elaia and Pitane. Eumenes was succeeded by his nephew Attalus I (241–197 BC) who was the first dynast of Pergamon to assume the title of 'king'. He succeeded in defeating the plundering Galatian Gauls, who had become an increasing problem in Anatolia, in 230 BC. Athena Nikephorus's (The Victory Bearer) temple was decorated with Epigonus' famous statues of the defeated Galatians. Attalus protected the Greek cities of Anatolia but harassed the Macedonians on the mainland, allying himself with Rome during the Macedonian Wars. A series of wars against Antiochus Hierax gave Pergamon control over much of Seleucid territory north of the Taurus Mountains, only to lose it under Antiochus III.[18] The dealings with Attalus proved to be the last time the Seleucids had any meaningful success in Anatolia as the Roman Empire lay on the horizon. After that victory, Seleucus's heirs would never again expand their empire.[12] Attalus also had to fight off neighbouring Bithynia, under King Prusias (228 – 182 BC).

Attalus' son, Eumenes II (197–159 BC) also collaborated with Rome to defeat Antiochus the Great at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BC. In the subsequent Peace of Apamea two years later he received Phrygia, Lydia, Pisidia, Pamphylia, and parts of Lycia from the former Seleucid possessions. He subsequently enlarged and adorned the city, building amongst other things the Great Altar. His brother Attalus II Philadelphus (c. 160–138 BC) fought with the Romans against Galatia and Bithynia and founded the cities of Philadelphia and Attalia.

The last of the Attalid kings was Attalus III (138–133 BC), son of Eumenes II, who bequeathed his kingdom to the Roman Republic. However, a pretender, calling himself Eumenes III briefly seized the throne until captured by the Romans in 129 BC. The lands occupied by Pergamon were divided up between Cappadocia and Pontus while the rest came directly under Rome. Pergamon had acted as a client state to Rome after Apamea, but after the death of Attalus III became the Roman province of Asia (Asiana).[18]

Cappadocia 323–17 BC

Cappadocia is a mountainous district in central Anatolia, north of the Taurus Mountains, and west of the Euphrates and the Armenian Highlands. It was bordered by Pontus in the North and Lycaonia to the west. At one time it included the area from Lake Tatta to the Euphrates and from the Black Sea to Cilicia. The northern portion, known as Cappadocia Pontus, became Pontus, while the centre and south was known as Greater Cappadocia, predominated by a plateau. At times the northern section constituted Paphlagonia. It was strategically situated on the overland route between Syria and the Seleucid territories in western Asia Minor, and hence important to maintain access. Even as a Persian satrapy it had retained a degree of autonomy.[18][19]

At the time of the conquest by Alexander the Great, the Persian satrap was Ariarathes I of Cappadocia (331–322 BC), and had himself proclaimed king. Ariarathes I refused to submit to Alexander the Great and remained unsubdued by the time of Alexander's death. Cappadocia was then given to Eumenes (323–321 BC) to govern, who had Ariarthes killed. Eumenes was replaced in 321 BC by Nicanor (321–316 BC). However, despite these Greek appointments Cappadocia continued to be governed by local rulers. Ariarthes had adopted his nephew Ariarthes II (301 – 280 BC), who fled to Armenia but then reconquered Cappadocia killing the local Macedonian satrap Amyntas in 301 BC. Nevertheless, he was permitted to continue to reign as a vassal of the Seleucids. Ariarthes's son Ariamnes (280 – 230 BC) continued the policy of increasing independence. His son in turn, Ariarathes III (255 – 220 BC) adopted the title of king, and sided with Antiochus Hierax against the Seleucid Empire and expanded his frontiers to include Cataonia.[18]

Ariarathes III's son, Ariarathes IV (220 – 163 BC) consolidated his power by marrying into the Seleucid dynasty, taking Antiochis, daughter of Antiochus the Great (222–187 BC) as his wife, and assisting him against the Romans. Although the Romans proved victorious at the Battle of Magnesia (190 BC) Ariarathes had another alliance which spared Cappadocia following the Treaty of Apamea (188 BC). His daughter Stratonice married Eumenes II of Pergamon (197–159 BC), a Roman ally. In this role he joined Eumenes in his struggle against Pontus. His son, Ariarathes V (163 – 130 BC) found himself in conflict with the Seleucid Emperor, Demetrius I Soter (161–150 BC) who attempted to replace him with his brother Orophernes forcing him to flee to Rome. The Romans restored him as a joint king with Orophernes in 157 BC by dividing the kingdom. Orophernes was reluctant to cede territory and with the support of Attalus II of Pergamon (160–138 BC) Ariarathes was victorious in 156 BC.[20] He then allied himself with Attalus II against Prusias II of Bithynia (182–149 BC). He died in 130 BC assisting the Romans in putting down the pretender Eumenes III of Pergamon. His efforts were rewarded by the granting of Lycaonia and Cilicia to his family.

The Cappadocian monarchy then fell victim to the ambitions of Pontus. Ariarathes' son, Ariarathes VI (130–116 BC) was related to the Pontine monarchy through his mother Nysa of Cappadocia. His uncle, Mithridates V of Pontus (150–120 BC) had the young king married to his daughter Laodice in order to bring Cappadocia under his control. Mithridates V's son, Mithridates VI (120–63 BC) then had Ariarathes murdered. Cappadocia was then briefly ruled by Nicomedes III of Bithynia (127– 94 BC), marrying Ariarathenes's widow, Laodice. Mithridates VI then ousted Nicomedes, replacing him with Aríarathes VI's son Ariarathes VII (116–101 BC), his mother Laodice acting as regent. Mithridates also had him killed and replaced with Mithridates own son, as Ariarathes IX (101–96 BC). In 97 BC there was a rebellion against this proxy monarchy and Ararathes VII's brother known as Ariarathes VIII was called upon but swiftly dealt with by Mithridates. The death of both of the sons of Ariarthanes VI effectively extinguished the dynasty. This turmoil then prompted Nicomedes to attempt to insert a pretender claiming to be a third brother. At this point Rome intervened, Mithridates withdrew, Ariarathes IX was deposed yet again and the Cappadocians were allowed to choose a new king, Ariobarzanes I (95-c. 63 BC).[21]

By this stage Cappadocia was effectively a Roman protectorate and Ariobarzanes required regular intervention from Rome to protect him from the incursions of Tigranes the Great of Armenia (95–55 BC). However, siding with Rome in the Third Mithridatic War against Pontus he was able to enlarge his domains before abdicating in favour of his son, Ariobarzanes II (c.63–c.51 BC). Although Cappadocia continued as an independent state longer than its neighbours, it continued to require help from Rome to maintain its borders. Rome also controlled the succession. Ariobarzanes II married Athenais Philostorgos II, daughter of Mithridates VI and was succeeded by his son Ariobarzanes III (51–c.42 BC) who added Lesser Armenia to his territory but was executed by the Romans for opposing their control, being succeeded by his brother Ariarathes X (42–36 BC) who fared little better being executed by Mark Anthony and replaced with Archelaus (38 BC – 17 AD) a Cappadocian nobleman. Archelaus survived by switching allegiance from Mark Anthony to Octavian, later Emperor Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD), at the Battle of Actium (31 BC) gaining Cilicia. He also united Cappadocia with Pontus by marrying with Augustus' blessing, the client queen Pythodorida of Pontus (8 BC – 38 AD). In 17 BC he was summoned to Rome by the new Emperor, Tiberius (14–37 AD) whom he had angered by supporting a rival, and Tiberius declared Cappadocia a Roman Province ending the kingdom. Pythodorida returned to Pontus, Lesser Armenia was given to his step-son Artaxias III (18 – 35 AD), and the remaining territories to his son.

Cilicia 323–67 BC

Cilicia lay at the eastern end of the Mediterranean coast, just north of Cyprus. It was separated from the Anatolian Plateau to the north and west by the Taurus Mountains, connected only by a narrow pass, the Cilician Gates. To the west lay Pamphylia, to the east the Amanus Mountains separated it from Syria. In ancient times Cilicia was naturally divided into two areas, Cilicia Trachaea (Κιλικία Τραχεία; Rugged or Rough Cilicia), a mountainous area in the west and Cilicia Pedias (Κιλικία Πεδιάς; Flat Cilicia, also Kilikia Leia or Smooth Cilicia), the flat plains to the east divided by the River Lamus, now called Limonlu Çayı. A major east-west trading route passed through it exiting through the Cilician Gates.[2]

Cilicia had historically been ruled by the Syennesis dynasty, with their seat at Tarsus.[18][22] Even as a Persian satrapy for some of the time, Cilicia was ruled by tributary kings. Following the division of Alexander the Great's empire Cilicia was governed by Philotas (323–321 BC), then Philoxenus. Following the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC Cilicia became a battleground between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires in their Syrian Wars. Following the partition of 301 BC after the Battle of Ipsus Pleistarchus the son of Antipater and brother of Cassander ruled it separately, but he was almost immediately expelled by Demetrius the son of Antigonus I the following year. Cilicia had a habit of changing hands frequently, Demetrius losing it in 286 BC and then regaining it.

Following the Treaty of Apamea in 188 BC, between the Romans and the Seleucid Antiochus III, Cilicia was left to Antiochus, despite losing most lands west of there.[23]

In the 2nd century BC, Cilicia was notorious for the pirates based along the southern Tracheian coast. After the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes (138–129) the Seleucid Empire had become reduced to Syria and adjacent Cilicia. At one stage the Seleucid Empire was divided with Philip I (95–84 BC) ruling in Cilicia while his twin Antiochus IX ruled in Damascus.[24] With the rise of more independent states in Asia Minor, Cilicia came under the hegemony of various surrounding kingdoms, sometimes partitioned. during the Mithridatic Wars (88–63 BC) between Rome and Pontus and their ally Armenia, Tigranes the Great of Armenia (95–55 BC) that state vastly expanded its borders at the expense of the Seleucids, and incorporated Cilicia c. 80 BC, until forced to retreat from the advancing Romans.[25]

Roman influence was being felt in Cilicia as early as 116 BC.[26] In 67 BC Pompey who had suppressed the pirates created the Roman province of Cilicia as the second province in Asia Minor, eventually stretching between the provinces of Asia to the west and Syria in the east, adding Cicilia Pedias in 63 BC. By the time of the Emperor Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD) Cicilia had been dismembered, divided between the provinces of Galatia and Syria and client rulers in Cilicia Trachea.[18]

In the 1st century BC Cilicia was tied to Pontus. Darius of Pontus being replaced by Rome with Polemon I in 37 BC. When Polemon died in 8 BC, his widow Pythodorida ruled Cilicia and Pontus. She was succeeded by her son Polemon II (38 BC – 74 AD) on her death, although he lost the Pontian throne in 62 AD.

Cilicia was a very diverse area, both geographically and demographically and parts of it remained difficult for any occupying power to subdue.[27] During this period, minor dynasts existed within Cilicia such as Zenophanes in Olba,[28][29] and Antipater of Derbe in Isauria and Tarcondimotus in northern Amanus.[30]

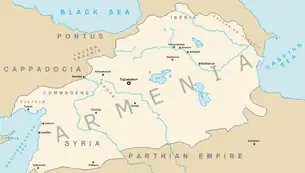

Armenia 331–1 BC

Armenia lay to the north-east of the Anatolian region, on the Armenian highlands to the south and west of the Caucasus. Its boundaries fluctuated during the 1st millennium BC but at times extended from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

Armenia in the 1st century BC formed a mountainous region in eastern Anatolia, bounded to the south by Syria and Mesopotamia and to the east by that part of Media known as Media Atropatene, which represents modern day Azerbaijan and the Euphrates River. To the west lay Cappadocia and Commagene. It included the area around Lake Van, the Araxes valley (emptying into the Caspian Sea), and reached north to Lake Sevan as far as Iberia in the lower Caucasus. The Armenian highlands were geographically separated from the Mesopotamian plains, and was approached through Sophene to the south west and across the Euphrates at Tomisa in Cappadocia. The horses bred on the Armenian lands made it attractive to its neighbours.[18]

A satrapy under the Persians, it was largely ruled by the Orontid dynasty. Mithrenes (331–333 BC), the local Persian commander surrendered to Alexander the Great following the Battle of Granicus (334 BC) and was appointed to be the local satrap as had been his father Orontes II (336–331 BC). With the death of Alexander and subsequent division of the empire in 323 BC, Armenia was granted to Neoptolemus (323–321 BC). Neoptolemus, however, conspired and was killed in battle with Eumenes in 321 BC. With the subsequent fall of Eumenes, Mithrenes re-assumed power (321–317 BC) and declared himself king. He was succeeded by Orontes III (317–260 BC) and relative stability apart from his unsuccessful struggles with the minor kingdom of Sophene on his south-western frontier. During this time the capital was moved from Armavir to Yervandashat in 302 BC. During this time Armenia fell under the Seleucid Empire in the tripartite division. However, the degree of control of the Seleucids, who were constantly at war, over Armenia varied. Under subsequent monarchs, including Orontes' son Sames (260 BC) and grandson Arsames I (260–228 BC) that grip was loosened further allowing Armenia to acquire not only Sophene but Commagene, the next minor kingdom to the west, bordering on Cilicia and Cappadocia. However, the enlarged kingdom became divided in the next generation, Xerxes (228–212 BC) ruling Sophene and Commagene, while his brother Orontes IV (212–200 BC) ruled Armenia.

However, Antiochus the Great, the Seleucid King (223–187 BC), led the last expansion of his kingdom, overthrowing and killing Orontes IV and bringing Armenia directly under Seleucid control in 212 BC, and appointing two satraps (strategos), Artaxias (Artaxerxes) and Zariadris. The retreat of the Seleucid forces from Europe and their defeat at the Battle of Magnesia (190 BC) allowed Armenia to throw off Seleucid rule, the satraps assuming kingship under a new Artaxiad dynasty (189 BC – 12 AD). Zariadris took the south (Sophene) following Xerxes' assassination. Artaxias I (190–160 BC) led a revolt against Antiochus.[18] He reunited Armenian-speaking peoples in the region, often divided by surrounding states. In this context, the Armenian lands to the west of the Euphrates were known as Armenia Minor (Lesser Armenia), as opposed to Greater Armenia to the east. Artaxias also moved the capital again, this time to Artashat (Artaxata). He was succeeded by his son Artavasdes I (160–115 BC) whose major problem was incursions by Parthians to the east.

The period of greatest Armenian expansion occurred with Tigranes II (The Great; 95–55 BC) who made it the most powerful state east of Rome, as the various kingdoms of western Anatolia were absorbed into the Roman sphere of influence. He consolidated his influence within Armenia, once again taking over Sophene after deposing Artanes he king. This was the period of the Mithridatic Wars (88–63 BC) between Pontus, his north western neighbour, and Rome. He formed an alliance with Mithridates VI of Pontus (120–63 BC), marrying his daughter Cleopatra. By acquiring Syria, Phoenicia and Cilicia he effectively reduced the Seleucid empire to a rump state. The aggressive behaviour of both Pontus and Armenia inevitably and fatally brought them into conflict with the eastward Roman expansion with the Armenians suffering a decisive defeat at the Battle of Tigranocerta (69 BC). By 67 BC Pompey had arrived in eastern Anatolia with the express purpose of crushing these two states. Tigranes surrendered in 66 BC, and Armenia became a client state. The remaining members of the dynasty, which eventually petered out in 1 BC, had an uneasy relationship with both Rome to the west and Parthia to the east. Rome saw Armenia as a buffer state in relation to Parthia, requiring frequent interventions by the Romans.

Minor kingdoms

Sophene and Commagene were among minor Anatolian states that at times were independent kingdoms and at others were annexed to surrounding territories. Both lay to the west of Armenia proper, adjoining Pontus, Cappadocia and Cilicia, from north to south.

Sophene

Sophene had been a province of ancient Armenia but became independent following the division of Alexander the Great's empire. At times it incorporated Commagene. It was nominally part of the Seleucid empire at least after 200 BC but with the weakening of that empire by the Romans after 190 BC it again became independent under Roman influence with Zariadres declaring himself king, before being annexed by Tigranes the Great of Armenia (c. 80 BC). It later became a Roman province. The capital city was Carcathiocerta, near Eğil, on the Tigris river.

Commagene

Commagene, a country on the west bank of the Euphrates was at times part of Sophene and of Armenia. As with Sophene it came more firmly under Seleucid control in the Antiochian expansion until 163 BC when Ptolemaeus (163–130 BC) revolted and established an independent state. Antiochus I Theos (70–38 BC) submitted to Pompey in 64 BC during his campaign against Armenia and Pontus, and allied Commagene with the Romans for which part of Mesopotamia was added to the kingdom. He managed to keep Commagene relatively independent until he was deposed by Mark Antony in 38 BC. Tiberius annexed Commagene to the province of Syria in 17 AD. Its capital was at Samosata near the Euphrates.[18]

Rhodes

The island of Rhodes, off the southwestern tip of Anatolia is not technically part of Anatolia, but formed an important strategic role in Anatolian history, formed alliances, and also ruled areas of southwestern Anatolia for a time. Under Persian rule Rhodes fell under the same satrap as the adjacent mainland areas. The Treaty of Apamea in (188 BC) established Roman control over western Anatolia and the retreat of the Seleucids from this area. The Republic of Rhodes, as an ally of Rome in the war, was granted former Seleucid lands sharing western Anatolia with Pergamon including Caria and Lycia, referred to as the Peræa Rhodiorum.[23] These lands were subsequently lost to Rome in the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC).[18]

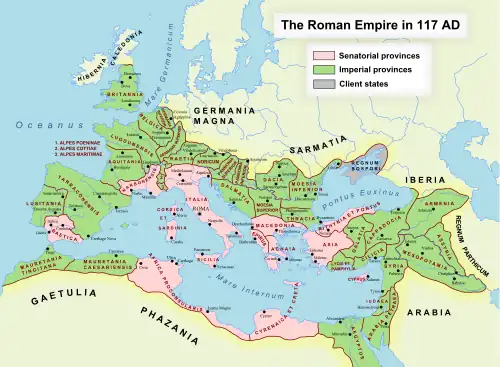

Roman period

Roman Republic 190 – 27 BC

By 282 BC Rome had subdued northern Italy, and as a result of the Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC) established supremacy over the Greek colonies of southern Italy. Shortly afterwards the Roman Republic became embroiled in the Punic Wars (264–146 BC) BC with Carthage in the western Mediterranean. As a result of these wars Rome found itself with overseas colonies and was now an imperial power. The next encounter with the Greeks arose from Macedonian expansion and consequent Macedonian Wars (214–148 BC). Direct invasion of Anatolia did not occur until the Seleucid Empire expanded its frontiers into Europe, and was crushed by Rome and its allies in 190 BC, forcing it to retreat to the eastern part of the region. Following this the major powers of western and central Anatolia (Pergamon, Bithynia, Pontus and Cappadocia) were frequently at war, with increasing Roman intervention politically and militarily. The Roman presence increased from sporadic intervention, to creating client states to direct rule by provincilisation.

Part of Roman foreign policy was the declaration of foreign states as socius et amicus populi romani (ally and friend of the Roman people) by treaty agreements.

Roman intervention in Anatolia 3rd – 1st centuries BC

The rule of Rome in Anatolia was unlike any other part of their empire because of their light hand with regards to government and organization. Controlling unstable elements within the region was made simpler by the bequeathal of both Pergamon and Bithynia to the Romans by their kings.[31]

Punic (264–146 BC) and Macedonian (214–148 BC) Wars

In the Second Punic War, Rome had suffered in Spain, Africa, and Italy because of the impressive strategies of Hannibal, the Carthaginian general. When Hannibal entered into an alliance with Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC) in 215 BC, Rome used a small naval force with the Aetolian League to help ward off Hannibal in the east and to prevent Macedonian expansion in western Anatolia. Attalus I of Pergamon (241–197 BC) the dominant western Anatolian power, traveled to Rome along with Rhodes and helped convince the Romans that war against Macedon was necessary. The Roman general Titus Quinctius Flamininus not only soundly defeated Philip's army in the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC, but also brought further hope to the Greeks when he said that an autonomous Greece and Greek cities in Anatolia was what Rome desired.[12]

Seleucid invasion of Europe and retreat from western Anatolia 196–188 BC

During the period just after Rome's victory, the Aetolian League desired some of the spoils left in the wake of Philip's defeat, and requested a shared expedition with the Seleucid emperor Antiochus III (223–187 BC) to obtain it. Despite warnings by Rome, Antiochus entered Thrace in 196 BC, and crossed into Greece by 192 BC, deciding to ally himself with the League. This was intolerable for Rome, and they soundly defeated him in Thessaly at Thermopylae in 191 BC, forcing his retreat to Anatolia, near Sardis.[12] Combining forces with the Romans, Eumenes II (197–159 BC) of Pergamon met Antiochus in the Battle of Magnesia in 189 BC. There Antiochus was overwhelmed by an intensive cavalry charge by the Romans and an outflanking maneuver by Eumenes. Because of the Treaty of Apamea the following year, Pergamon was granted all of the Seleucid lands north of the Taurus mountains (Phrygia, Lydia, Pisidia, Pamphylia, and parts of Lycia) and Rhodes was given all that remained (part of Lycia and Caria).

A stronger Pergamon suited Roman interests as a buffer state between the Aegean and the Seleucid Empire. However, Rome needed to intervene on a number of occasions to ensure the integrity of the enlarged territory, including wars against Prusias I of Bithynia (187–183 BC) and Pharnaces I of Pontus (183–179 BC). Following Eumenes' support for Rome in the Third Macedonian War (170 – 168 BC) Macedon's power had been crushed and Rome no longer felt the need for such a strong Pergamon, and the Senate set about weakening it, negotiating with Eumenes' brother Attalus II Philadelphus (c. 160–138 BC) and Prusias while declaring the recently defeated Galatians (184 BC) free. By the time his brother Attalus II succeeded him, Pergamonian power was on the decline, and the last dynast Attalus III (138–133 BC) bequeathed his kingdom to Rome. After a brief revolt by Eumenes III 133–129 BC, it became the Province of Asia under Roman consul Aquillius Manius the Elder.[31]

Involvement with central Anatolian politics 190–17 BC

The interior of Anatolia had been relatively stable despite occasional incursions by the Galatians until the rise of the kingdoms of Cappadocia and Pontus in the 2nd century BC.

Cappadocia under Ariarathes IV (220 – 163 BC) was initially allied with the Seleucids in their war against Rome. However, Ariarathes changed alliances following the Battle of Magnesia (190 BC), becoming Rome's friend, and joined Pergamon against Pontus. His son, Ariarathes V Philopator (163 – 130 BC), continued his father's policy of alliance with Rome, joining Rome and Attalus II of Pergamon (160–138 BC) in 154 BC in a war against Prusias II of Bithynia (182–149 BC). He died assisting Rome overcoming the pretender Eumenes III of Pergamon (133–129 BC) in 131 BC. His reign was marked by internal conflict that required Rome to intervene to restore him. From this stage onward Rome increasingly intervened in Cappadocian affairs, assisting it against Pontus and Armenia, creating a client state in 95 BC, and a province in 17 BC.

Pontus had been an independent kingdom since the rule of Mithridates (302 – 266 BC) when the threat of Macedon had been removed. Pontus maintained an uneasy alliance with the Seleucids and was involved in a number of regional wars, particularly under Pharnaces I (c. 190 – c. 155 BC) some of which attracted Roman intervention. There was a brief period of collaboration with Rome under Mithridates V (c. 150 – 120 BC) assisting the Romans in suppressing a revolt by the pretender of Pergamon, Eumenes III. This all changed under Mithridates VI (120 – 63 BC) whose aggressive expansionist powers swept through Anatolia but soon brought him into direct conflict with Rome and the ultimately fatal Mithridatic Wars (88–63 BC).

Bithynia, the other major kingdom in western Anatolia, had varying relations with Rome, and in particular its ally Pergamon. The last monarch, Nicomedes IV (94 – 74 BC) bequeathed his kingdom to Rome, precipitating the Mithridatic Wars between Rome when Pontus claimed Bithynia.[13]

Pontus and the Mithridatic Wars 89–63 BC

Mithridates VI of Pontus (120–63 BC) quickly set about creating his own empire. In his first thrust to extend his frontiers along the Black Sea litoral he avoided drawing the attention of Rome. Rome was preoccupied with other issues that precluded it paying attention to events east of the Province of Asia. This included the Jugurthan 111–104 BC and Cimbric Wars (113–101 BC) as well as dealing with the Scordisci.

Rome, however, noticed once Mithridates turned his eye west in 108 BC, partitioning Paphlagonia with Nicomedes III of Bithynia (127–94 BC). They not only ignored Roman orders to withdraw but marched into Galatia. Next was Cappadocia, where Mithridates installed a nephew, Ariarathes VII (116–101 BC), whom he had assassinated shortly afterwards. About this time he sent envoys to Rome to elicit support for his claims, but was not successful and instead rome dispatched Gaius Marius in c. 99 BC to take him to task. Amongst further turmoil in that kingdom, he again sent to Rome for support of his latest candidate as did his rival. The Senate promptly ordered Mithridates out of Cappadocia (and Nicomedes out of Paphlagonia). Mithridates appears to have withdrawn by 89 BC, while Sulla the Governor of Cilicia was dispatched to install a new Cappadocian king (Ariobarzanes I (95–c.63 BC).[32]

By 91 BC Rome was again distracted by war, this time against Italian rebels known as the Social War (91–88 BC), when two critical events occurred. Tigranes the Great (95–55 BC) ascended the throne of Armenia in 95 BC and allied himself to Mithridates through marriage, while Nicomedes died in 94 BC leaving his kingdom to his young son Nicomedes IV (94–74 BC), creating a potential opportunity for territorial expansion. Tigranes marched into Cappadocia, Ariobarzanes fled to Rome and Nicomedes was expelled. Rome became alarmed, ordered the restoration of both monarchs and sent Manius Aquillius and Manlius Maltimus to deal with the problem, and Pontus and Armenia drew back.[33]

First war 89–84 BC

By now both Bithynia and Cappadocia were ruled by Roman protégés and were indebted to Rome who urged them to invade Pontus, a fatal miscalculation. Nicomedes invaded Pontus, Mithridates complained to Rome, boasted of his power and allies and unwisely hinted that Rome was vulnerable. The Roman Commissioners declared a state of war and the First Mithridatic War (89–84 BC) was launched.[34]

The war went well initially for the allies during 89–88 BC, since Rome was still involved in the Social War, taking Phrygia, Mysia, Bithynia, parts of the Aegean Ccoast, Paphlagonia, Caria, Lycea, Lycaonia and Pamphylia. Aquillius was defeated in the first direct engagement with the Romans, in Bithynia although the troops were actually raised locally. The other Roman commander was C. Cassius, governor of Asia, whose seat was at Pergamon, and as Mithridates overran the province, both fled from the mainland. Aquillius was handed back to Mithridates who executed him. Roman rule in Anatolia had been crushed, although a few areas of Asia Minor managed to hold out.

Although Sulla was then appointed to deal with Mithridates, events moved very slowly. However, worse was to come later in 88 BC. the 'Asiatic (or 'Ephesian') Vespers', was the slaughter of tens of thousands of Romans and Italians ordered by Mithridates.[35] Having cleansed Asia Minor of Romans, Mithridates looked further afield, his next victim that year being Rhodes, but it held out, and he moved on to the Aegean islands, taking Delos. A number of mainland Greek states welcomed the advance of the Pontian monarch, Sulla not having set out for Greece from Italy until 87 BC. Meanwhile, Mithridates had overcome the Roman army in Macedonia. When the two armies finally met, Sulla inflicted two defeats on the Pontic forces at the battles of Chaeronea (86 BC) and Orchomenus (85 BC) restoring Roman rule to Greece. Pontus sued for peace, faced with widespread revolts in Anatolia. Mithridates was to give up Asia and Paphlagonia, to hand back Bithynia to Nicomedes and Cappadocia to Ariobarzanes. In return he was allowed to continue ruling in Pontus as an ally of Rome, having abandoned all territories south and west of the Halys.[12][36]

Mithridates' problems were further complicated by a 'rogue' Roman army dispatched by Sulla's enemies in Rome, commanded by Flaccus and then by Gaius Flavius Fimbria which crossed from Macedonia through Thrace to Byzantium and ravaged western Asian Minor before inflicting a defeat on the Pontic forces on the Rhyndacus river. This finally led Mithridates to accept Sulla's terms (Treaty of Dardanos).[37]

Sulla set about re-organising the Roman administration in Western anatolia until 84 BC. Those cities that had resisted Mithridates were rewarded, for instance Rhodes regained the Peraea lost in the Macedonian wars. Those that had collaborated were forced to pay reparations. The combined effects of the war and aftermath were ruinous for the region and piracy abounded. Mithradates himself faced internal problems

Second war 83–81 BC

Given that many Romans thought that Mithridates had got off rather lightly following the first war, provocation was almost inevitable. Sulla left Ephesus in 84 BC to return to Rome and make war on his enemies, where he would eventually become dictator. He left Lucius Licinius Murena to govern the province of Asia. Murena proceeded to intervene in Cappadocia in 83 BC, where Mithrodates was also interfering with the recently restored Ariobarzanes I (95–63 BC). After two further raids with less justifiable pretexts, Mithridates retaliated, pursuing Murena and inflicting a number of defeats on Murena until Sulla (who had less territorial ambition than Murena) intervened and both antagonists withdrew to their former positions.

Murena had refused to recognise the treaty on a technicality and the Senate refused to ratify it despite Mithridates' efforts. Mithridates realised Rome would remain a potential threat but nevertheless continued to respect the treaty, but made military preparations for the possibility of a third war. The next step by Rome was to restore control over the areas to the south east which they had lost in the first war (Pamphylia, Pisidia and Lycaonia). So the area was brought under provincial administration by creating Cilicia (which technically included none of the historical Cilician territory further east) under Publius Servilius, as pro-Consul (78–74 BC). Servilius set about cleansing the Pamphylian coast of pirates before subduing Pisidia and Isauria. The building of military roads through Cilicia now created a new potential threat to Mithridates and Pontus.

Third war 75–63 BC

When Nicomedes IV of Bithynia (94–74 BC) died, leaving his kingdom to Rome, he created not only a potential power vacuum, but further encircled Pontus. The Senate had instructed the propraetor of the province of Asia to take over Bithynia. This coincided with the death of Servilius' successor as proconsul of Cilicia, which then came under the command of Lucius Licinius Lucullus, while Bithynia was assigned to Marcus Aurelius Cotta. Both consuls were instructed to prepare to pursue Mithridates, by Cicero.

By the time Lucullus arrived in 73 BC, Mithridates was anticipating him. Lucullus was assembling his legions in northern Phrygia, when Mithridates advanced rapidly through Paphlagonia into Bithynia, where he joined his naval forces and defeated the Roman fleet commanded by Cotta at the Battle of Chalcedon. Having besieged Cotta in Chalcedon, Mithridates continued west towards Cyzicus, in Mysia. Lucullus went to relieve Cotta and then moved on to Cyzicus, which Mithridates was besieging. The city held out and Mithridates withdrew suffering heavy losses at the Battles of the Rhyndacus and Granicus in 72 BC. After a series of naval defeats Mithridates fell back to Pontus. He had also sent troops into Lycaonia and the southern regions of Asia to create support amongst Pisidians and Isaurians, but these were now repelled by the Galatians, under Deiotarus.

Lucullus then resumed his original plan and advanced through Galatia and Paphlagonia to Pontus in 72 BC. By 71 BC he was through the Iris and Lycus valleys and into Pontus where he engaged Mithridates at Cabira. The result was disastrous for the Pontic forces, and Mithridates fled to Armenia. The Romans then set about subduing Pontus and Lesser Armenia while trying to persuade Mithridates, now the guest of Tigranes the Great to surrender. Tigranes spurned the Roman overtures and indicated he was prepared to fight, so Lucullus prepared to invade Armenia in 70 BC. In 69 he marched through Cappadocia to the Euphrates, crossing it at Tomisa and entering Sophene and the lands which Tigranes had recently acquired from the Seleucids and heading for the new imperial capital of Tigranocerta. There Tigranes found him besieging the city, and in the ensuing battle, was routed, fleeing northwards.[12][39]

To proceed further required ensuring the neutrality of the next empire, the Parthians whom Tigranes had also wooed. In 68 BC Lucullus made some advances into northern Armenia but was hampered by the weather and wintered in the south. His strategy had been to dismember Armenia into its former kingdoms. By 67 BC the Roman forces in Pontus were coming increasingly under attack by Mithridates who scored a major victory at Zela. Lucullus' troops were also tiring and becoming dissatisfied. Lucullus withdrew from Armenia but not in time to prevent the defeat at Zela.[40]

The failure of Lucius Licinius Lucullus to rid Rome once and for all of Mithridates brought a lot of opposition at home, some fueled by the great Roman consul Pompey. Lucullus was formally replaced in 67 BC by Marcius Rex, ordered to deal with the Cilician pirate problem, that was threatening the Roman food supply in the Aegean, and Acilius Glabrio to take over the eastern command. Lucullus withdrew back to Galatia and Mithridates promptly recovered all his lost territory. Meanwhile, the republic was changing the administrative governance of Anatolia to the praetorian model in 68 BC.