Sino-Russian border conflicts

The Sino-Russian border conflicts (1652–1689) were a series of intermittent skirmishes between the Qing dynasty of China, with assistance from the Joseon dynasty of Korea, and the Tsardom of Russia by the Cossacks in which the latter tried and failed to gain the land north of the Amur River with disputes over the Amur region. The hostilities culminated in the Qing siege of the Cossack fort of Albazin in 1686 and resulted in the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 which gave the land to China.

| Sino-Russian border conflicts[1] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

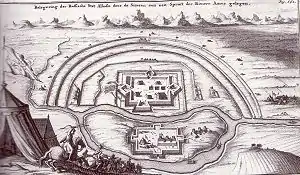

Qing Empire forces storming the fort of Albazin | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

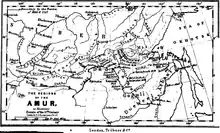

Background

The southeast corner of Siberia south of the Stanovoy Range was twice contested between Russia and China. Hydrologically, the Stanovoy Range separates the rivers that flow north into the Arctic from those that flow south into the Amur River. Ecologically, the area is the southeastern edge of the Siberian boreal forest with some areas good for agriculture. Socially and politically, from about 600 AD, it was the northern fringe of the Chinese-Manchu world. Various Chinese dynasties would claim sovereignty, build forts and collect tribute when they were strong enough. The Ming dynasty Nurgan Regional Military Commission[4] built a fort on the Northern bank of the Amur at Aigun,[5] and established an administrative seat at Telin, modern Tyr, Russia above Nikolaevsk-on-Amur.[6]

Russian expansion into Siberia began with the conquest of the Khanate of Sibir in 1582. By 1643 they reached the Pacific at Okhotsk. East of the Yenisei River there was little land fit for agriculture, except Dauria, the land between the Stanovoy Range and the Amur River which was nominally subject to the Qing dynasty.[7][8][9]

In 1643, Russian adventurers spilled over the Stanovoy Range, but by 1689 they were driven back by the Qing. The land was populated by some 9,000 Daurs on the Zeya River, 14,000 Duchers downstream and several thousand Tungus and Nivkhs toward the river mouth. The first Russians to hear of Dauria were probably Ivan Moskvitin and Maxim Perfilev about 1640.[7][8][9]

In 1859/60 the area was annexed by Russia and quickly filled up with a Russian population.

Timeline

1639-1643 : Qing Campaign against the indigenous rulers

- December 1639-May 1640 : 1st battle - the native siberians and the Qing participated in the Battle of Gualar (Russian: селение Гуалар) : between 2 regiments of Manchu bannermen and a detachment of 500 Solon-Daurs[10] led by the Solon-Evenk leader Bombogor (Chinese: 博木博果爾 or 博穆博果爾 pinyin:Bomboguoer) while the second native leader Bardači (Chinese: 巴爾達齊 or 巴爾達奇 Bā'ěrdáqí) kept neutral.

- September 1640 : 2nd battle - the native Siberians and the Qing participated in the Battle of Yaksa (Russian: Якса): between the natives (Solon, Daur, Oroqen) and the Manchus.

- May 1643 : In the 3rd battle, The native tribes submitted to the Qing Empire.

1643-1644 : Vasili Poyarkov

- Winter 1643 - Spring 1644 : a detachment of a Russian expedition led by the Cossack Vasili Poyarkov explored the stream of the Jingkiri river, present-day Zeya, and the Amur rivers. Vassili Poyarkov traveled from Yakutsk south to the Zeya River. He then sailed down the Amur River to its mouth and then north along the Okhotsk coast, returning to Yakutsk three years later.[7][8][9]

1649-1653 : Yerofey Khabarov

- 1650-1651 : In 1649 Yerofei Khabarov found a better route to the upper Amur and quickly returned to Yakutsk where he recommended that a larger force be sent to conquer the region. He returned the same year and built winter quarters at Albazin at the northernmost point on the river.[7][8][9] He occupied the Daur's fort Albazin after subduing the Daurs led by Arbaši (Chinese: 阿尔巴西 Ā'ěrbāxī). The Russian conquest of Siberia was accompanied by massacres due to indigenous resistance to colonization by the Russian Cossacks, who violently suppressed the natives. The Russian Cossacks were named luocha (羅剎), after Demons found in Buddhist mythology, by the Amur natives because of their cruelty towards the Amur tribes people, who were subjects of the Qing.[11]

- March 24, 1652 : Battle of Achansk

Next summer he sailed down the Amur and built a fort at Achansk (Wuzhala (乌扎拉)) probably near present-day Khabarovsk. Again there was fighting and the natives called for the assistance of the Qing. On 24 March 1652, Achansk was unsuccessfully attacked by a large Qing force [600 Manchu soldiers from Ninguta and about 1500 Daurs and Duchers led by the Manchu general known as Haise (海色),[12] or Izenei (Изеней or Исиней).[13] Haise was later executed for his poor performance.[14] As soon as the ice broke up Khabarov withdrew upriver[15] and built winter quarters at Kumarsk. In the spring of 1653 reinforcements arrived under Dmitry Zinoviev. The two quarreled, Khabarov was arrested and escorted to Moscow for investigation.[7][8][9]

Cattle and horses in the hundreds were looted and 243 ethnic Daur Mongolic girls and women were raped by Russian Cossacks under Yerofey Khabarov when he invaded the Amur river basin in the 1650s.[16]

1654-1658 : Onufriy Stepanov

- March–April 1655 : Siege of Komar

- 1655 : Russian Tsardom has established a "military governor of the Amur region".

- 1657 : 2nd Battle of Sharhody.

Onufriy Stepanov was left in charge with about 400-500 men. They had little difficulty plundering the natives and defeating the local Qing troops. The Qing responded with two policies. First they ordered the local population to withdraw, thereby ending the grain production that had attracted the Russians in the first place. Second they appointed the experienced general Sarhuda (who himself was from the Nierbo village from the mouth of Sungari) as the garrison commander at Ninguta. In 1657 he built more than 40 ships at the village of Ula (modern Jilin).. In 1658 a large Qing fleet under Sarhuda caught up with Stepanov and killed him and about 220 Cossacks. A few escaped and became freebooters.[7][8][9]

1654-1658 : The Sino-Korean allied expeditions against Russians

In the following operations significant Korean forces under King Hyojong were included into Manchu-led troops. The campaigns became known in Korean historiography as Naseon Jeongbeol (나선정벌, literally Russian campaign).

- January 1654 : the first time a Korean contingent arrived to join a Manchu army near Ninguta.

- July 1654 : Battle of Hutong (on lower reaches of the Sungari at the present-day Yilan) between a joint Korean-Manchu army of 1500 men led by Byeon Geup (Hangul: 변급 Hanja: 邊岌) against 400-500 Russians.

- 1658 : Big warships capable of fighting Russian ships were built by Han Chinese shipbuilders for the Qing forces.[17] Sarhuda's Qing fleet from Ninguta, including a large Korean contingent led by Shin Ryu sails down the Sungari into the Amur, and meets Onufriy Stepanov's smaller fleet from Albazin. In a naval battle in the Amur a few miles downstream from the mouth of the Sungari (July 10, 1658). The 11-ship Russian flotilla is destroyed (the survivors flee on just one ship), and Stepanov himself dies.[18]

By 1658 the Chinese had wiped out the Russians below Nerchinsk and the deserted land became a haven for outlaws and renegade Cossacks. In 1660 a large band of Russians was destroyed. They had some difficulty pursuing the Cossacks since their own policy had removed most of the local food. In the 1670s the Chinese attempted to drive the Russians away from the Okhotsk coast, reaching as far north as the Maya River.[7][8][9]

1665-1689: Albazin

In 1665 Nikifor Chernigovsky murdered[19] the voyvoda of Ilimsk and fled to the Amur and reoccupied the fort at Albazin, which became the center of a petty kingdom which he named Jaxa. In 1670 it was unsuccessfully attacked. In 1672 Albazin received the Czar's pardon and was officially recognized. From 1673 to 1683 the Qing dynasty were tied up suppressing a rebellion in the south, the Revolt of the Three Feudatories. In 1682 or 1684 a voyvoda was appointed by Moscow.[7][8][9]

After extensive reconnaissance, the Qing made their first attempt to conquer Albazin in 1685. At the time Albazin was a wooden fort with only 300 muskets, 3 cannons, and low stocks of gunpowder; regardless, the Chinese concluded that it could not be taken from its tiny garrison unless "red barbarian cannons" (Hongyipao) were used. Three thousand Qing soldiers initially assailed the fort. A detachment made a feint on the south of the fort, while other soldiers secretly moved Hongyipao to the north of the fort and to its sides, to carry out a pincer attack. In total, the Qing force included 100-150 light artillery, 40-50 large siege guns, and 100 musketeers, with the rest of the men using traditional weapons. On the first day, 100 Russians were killed or wounded by the massive artillery barrage. After the wooden walls were set ablaze, the Russians surrendered and acknowledged Qing suzerainty.[20]

After this, the Russian garrison was ordered to build more powerful walls. With the help of Prussian soldier Afanasii Ivanovich Beiton (who was second in command of the fort), the walls were eventually built up to a height of five and a half meters and a thickness of seven and a half meters. In July 1686, the Qing sent another force of 3,000 troops (chiefly cavalry and including 30-40 "newly cast" cannons), supported by 150 supply boats manned by 3,000 to 6,000 more men, to retake the fort from the garrison of 736 Russian soldiers and militia (who had 11 cannons). The Russians rejected a Qing demand for surrender, and another battle ensued on July 18. Over the next few weeks, the Qing made various attempts to take the fort, but were always driven back with heavy losses, while Russian combat losses were negligible. The Russians even began sallying out for counterattacks to destroy Qing siege engines, one sally killing 150 Chinese troops for the loss of only 21 Russians. The Qing were befuddled by the design of the fort which, like contemporary European artillery forts, often left the Chinese soldiers caught in crossfires when they attempted to place their siege lines and artillery according to traditional tactics. The Qing general, Langtan, abandoned assaults in August and instead decided to starve the fort out by blocking Russian access to the nearby river. Eventually, the Qing investment in Albazin became so large that the fortifications of the siege camps dwarfed those of Albazin itself. Moscow sent elite musketeers to relieve the fort but the Qing controlled all approaches and no sled or sleigh could slip in. Both armies suffered from disease and starvation: Russian combatants and civilians alike died en masse from scurvy, typhus, and cholera, while the Chinese starved and froze outside the walls and were sometimes driven to cannibalism. By November, 600 Russian men and more than 1,500 Qing soldiers had died. In October 1686, Russian envoys arrived in Beijing from Moscow requesting peace. In December, a messenger from the Qing emperor arrived at the siege lines announcing a pause to the siege, and that his men, as a show of good faith, were to offer food and medicine to the remaining Russians, of which there were only 24.[21]

Albazin was eventually ceded to the Qing in the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk, in exchange for trading privileges in Beijing and the right to keep the city of Nerchinsk.

1685-1687 : The Albazin/Yakesa Campaign

Former Ming dynasty loyalist Han Chinese troops who had served under Zheng Chenggong and who specialized at fighting with rattan shields and swords (Tengpaiying) 藤牌营 were recommended to the Kangxi Emperor to reinforce Albazin against the Russians. Kangxi was impressed by a demonstration of their techniques and ordered 500 of them to defend Albazin, under Lin Xingzhu (Chinese: 林兴珠) and He You (Chinese: 何佑), former Koxinga followers, and these rattan shield troops did not suffer a single casualty when they defeated and cut down Russian forces traveling by rafts on the river, only using the rattan shields and swords while fighting naked.[22][23][24]

- May–July 1685 : The siege of Albazin - The Qing used former Ming loyalist Han Chinese naval specialists who had served under the Zheng family in Taiwan in the siege of Albazin.[25] The Russians were fought against by the Taiwan based former soldiers of Koxinga.[26] The nautical military understanding of the former Taiwan sailors were the reason for their participation in the battles.[27]

- July–October 1686 : The siege of New Albazin.

see also Outer Manchuria

"[the Russian reinforcements were coming down to the fort on the river] Thereupon he [Marquis Lin] ordered all our marines to take off their clothes and jump into the water. Each wore a rattan shield on his head and held a huge sword in his hand. Thus they swam forward. The Russians were so frightened that they all shouted: 'Behold, the big-capped Tartars!' Since our marines were in the water, they could not use their firearms. Our sailors wore rattan shields to protect their heads so that enemy bullets and arrows could not pierce them. Our marines used long swords to cut the enemy's ankles. The Russians fell into the river, most of them either killed or wounded. The rest fled and escaped. Lin Hsing-chu had not lost a single marine when he returned to take part in besieging the city." written by Yang Hai-Chai who was related to Marquis Lin, a participant in the war[28]

Most of the Russians withdrew to Nerchinsk, but a few joined the Qing, becoming the Albazin Cossacks at Peking. The Chinese withdrew from the area, but the Russians, hearing of this, returned with 800 men under Aleksei Tolbuzin and reoccupied the fort. Their original purpose was merely to harvest the local grain, a rare commodity in this part of Siberia. From June 1686, the fort was again besieged. Either the siege was raised in December when the armies learned that the two empires were engaged in peace negotiations,[29] or the fort was captured after an 18-month siege and Tolbuzin was killed.[30] At that time less than 100 defenders were left alive.[7][8][9]

Treaties

In 1689, by the Treaty of Nerchinsk, the Russians abandoned the whole Amur country including Albazin. The frontier was established as the Argun River and the Stanovoy Range. In 1727 the Treaty of Kyakhta confirmed and clarified this border and regulated Russo-Chinese trade.

In 1858, almost two centuries after the fall of Albazin, by the Treaty of Aigun, Russia annexed the land between the Stanovoy Range and the Amur (commonly referred to in Russian as Priamurye, i.e. the "Lands along the Amur"). In 1860, with the Convention of Beijing, Russia annexed the Primorye (i.e. the "Maritime Region") down to Vladivostok, an area that had not been in contention in the 17th century. Those treaties allowed the Amur Annexation.

See also

References

- Wurm, Mühlhäusler & Tryon 1996, p. 828.

- CJ. Peers, Late Imperial Chinese Armies 1520-1840, 33

- China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia By Peter C. Perdue Published by Harvard University Press, 2005

- L. Carrington Godrich, Chaoying Fang (editors), "Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644". Volume I (A-L). Columbia University Press, 1976. ISBN 0-231-03801-1

- Du Halde, Jean-Baptiste (1735). Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique et physique de l'empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie chinoise. Vol. IV. Paris: P.G. Lemercier. pp. 15–16. Numerous later editions are available as well, including one on Google Books. Du Halde refers to the Yongle-era fort, the predecessor of Aigun, as Aykom. There seem to be few, if any, mentions of this project in other available literature.

- Li, Gertraude Roth (2002). "State Building before 1644". In Peterson, Willard J. (ed.). The Ch'ing Empire to 1800. Cambridge History of China. Vol. 9. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47771-0.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce (2007). The Conquest of a Continent: Siberia and the Russians. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8922-8.

- G. Patrick March, Eastern Destiny: the Russians in Asia and the North Pacific, 1996.

- А.М.Пастухов (A.M. Pastukhov) К вопросу о характере укреплений поселков приамурских племен середины XVII века и значении нанайского термина «гасян» Archived 2011-10-01 at the Wayback Machine (Regarding the fortification techniques used in the settlements of the Amur Valley tribes in the mid-17th century, and the meaning of the Nanai word "гасян" (gasyan)) (in Russian)

- Kang 2012, p. 26.

- Gong, Shuduo; Liu, Delin (2007). 图说清. 知書房出版集團. p. 66. ISBN 978-986-7151-64-3. (Although this particular book seems to misspell 海色 as 海包 (Haibao))

- Август 1652 г. Из отписки приказного человека Е.П. Хабарова якутскому воеводе Д.А. Францбекову о походе по р. Амуру. Archived 2011-10-04 at the Wayback Machine An excerpt from Khabarov's report to the Yakutsk Voivode D.A.Frantsbekov, August 1652.) (in Russian)

- Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office. p. 632.

Haise was executed for this disgrace

- Оксана ГАЙНУТДИНОВА (Oksana Gainutdinova) Загадка Ачанского городка Archived 2007-08-13 at the Wayback Machine (The mystery of Fort Achansk)

- Ziegler, Dominic (2016). Black Dragon River: A Journey Down the Amur River Between Russia and China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Penguin. p. 187. ISBN 978-0143109891.

- Kang 2012, p. 31.

- A.M. Pastukhov, "Корейская пехотная тактика самсу в XVII веке и проблема участия корейских войск в Амурских походах маньчжурской армии Archived 2012-07-08 at archive.today " (Korean infantry tactic samsu (三手) in the 17th century, and the issues related to the Korean troops' participation in the Manchus' Amur campaigns) (in Russian)

- Ravenstein, The Russians on the Amur, 1860(sic), Google Books

- Andrade 2017, pp. 221–222.

- Andrade 2017, pp. 225–230.

- Robert H. Felsing (1979). The Heritage of Han: The Gelaohui and the 1911 Revolution in Sichuan. University of Iowa. p. 18.

- Louise Lux (1998). The Unsullied Dynasty & the Kʻang-hsi Emperor. Mark One Printing. p. 270.

- Mark Mancall (1971). Russia and China: their diplomatic relations to 1728. Harvard University Press. p. 338. ISBN 9780674781153.

- R. G. Grant (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. DK Pub. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-7566-1360-0.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for Modern China. Norton. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-0-393-30780-1.

- Jenne, Jeremiah (September 6, 2016). "Settling Siberia: Nerchinsk, 1689". The World of Chinese. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- Lo-shu Fu (1966). A Documentary Chronicle of Sino-Western Relations, 1644-1820: Translated texts. Published for the Association for Asian Studies by the University of Arizona Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780816501519.

- March, chapter 5

- John J. Stephen, The Russian Far East, 1994,page 31

Works cited

- Andrade, Tonio (2017). "The Renaissance Fortress". The Gunpowder Age. Princeton University Press. pp. 211–234. doi:10.1515/9781400874446-016. ISBN 978-1-4008-7444-6. JSTOR j.ctvc77j74.18.

- Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-76595-8.

- Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-76596-5.

- Felsing, Robert H. (1979). The Heritage of Han: The Gelaohui and the 1911 Revolution in Sichuan (Thesis). OCLC 192098907. ProQuest 302906101.

- Grant, R. G. (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat (illustrated ed.). Dk Pub. ISBN 0756613604. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Kang, Hyeokhweon (2012). "Big Heads and Buddhist Demons: The Korean Military Revolution and Northern Expeditions of 1654 and 1658". Emory Endeavors in History: Transnational Encounters in Asia (PDF). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 26–47. ISBN 978-1-4751-3879-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-12-07. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- Kim, Loretta Eumie (2009). Marginal constituencies: Qing borderland policies and vernacular histories of five tribes on the Sino-Russian frontier (Thesis). OCLC 426251942. ProQuest 304891316.

- Lux, Louise (1998). The Unsullied Dynasty & the Kʻang-hsi Emperor. Mark One Printing. ASIN B0029LDCSA. OCLC 606335604.

- Mancall, Mark (1971). Russia and China: Their Diplomatic Relations to 1728. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-78115-3.

1. Page 133 -152 China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia By Peter C. Perdue Published by Harvard University Press, 2005

- Stephan, John J. (1994). The Russian Far East: A History. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2701-3.

- Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T., eds. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Maps. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.