Acadia National Park

Acadia National Park is an American national park located along the mid-section of the Maine coast, southwest of Bar Harbor. The park preserves about half of Mount Desert Island, part of the Isle au Haut, the tip of the Schoodic Peninsula, and portions of 16 smaller outlying islands. It protects the natural beauty of the rocky headlands, including the highest mountains along the Atlantic coast. Acadia boasts a glaciated coastal and island landscape, an abundance of habitats, a high level of biodiversity, clean air and water, and a rich cultural heritage.

| Acadia National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

| |

Location in the United States  Location in Maine | |

| Location | Hancock & Knox counties, Maine, United States |

| Nearest city | Bar Harbor |

| Coordinates | 44°21′N 68°13′W |

| Area | 49,075 acres (198.60 km2) 861.46 acres (348.62 ha; 3.4862 km2) private (in 2017)[1] |

| Established | July 8, 1916 (as Sieur de Monts National Monument) February 26, 1919 (as Lafayette National Park) January 19, 1929 (as Acadia National Park)[2] |

| Visitors | 2,669,034 (in 2020)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Official website |

The park contains the tallest mountain on the Atlantic Coast of the United States (Cadillac Mountain), exposed granite domes, glacial erratics, U-shaped valleys, and cobble beaches. Its mountains, lakes, streams, wetlands, forests, meadows, and coastlines contribute to a diversity of plants and animals. Woven into this landscape is a historic carriage road system financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr.[4] In total, it encompasses 49,075 acres (19,860 ha; 76.680 sq mi; 198.60 km2) as of 2017.

Acadia has a rich human history, dating back more than 10,000 years ago with the Wabanaki people. The 17th century brought fur traders and other European explorers, while the 19th century saw an influx of summer visitors, then wealthy families. Many conservation-minded citizens, among them George B. Dorr (the "Father of Acadia National Park"), worked to establish this first U.S. national park east of the Mississippi River and the only one in the Northeastern United States. Acadia was initially designated Sieur de Monts National Monument by proclamation of President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, then renamed and redesignated Lafayette National Park in 1919. The park was renamed Acadia National Park in 1929.

Recreational activities from spring through autumn include car and bus touring along the park's paved loop road; hiking, bicycling, and horseback riding on carriage roads (motor vehicles are prohibited); fishing; rock climbing; kayaking and canoeing on lakes and ponds; swimming at Sand Beach and Echo Lake; sea kayaking and guided boat tours on the ocean; and various ranger-led programs. Winter activities include cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, snowmobiling, and ice fishing. Two campgrounds are located on Mount Desert Island, another campground is on the Schoodic Peninsula, and five lean-to sites are on Isle au Haut. The main visitor center is at Hulls Cove, northwest of Bar Harbor. Park visitation has been steadily increasing in Acadia over the past decade, with 2021 seeing a record count of 4.07 million visitors.[5]

Geography

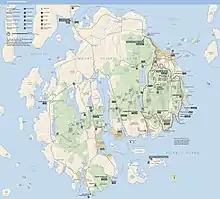

(click map to enlarge)

The park includes mountains, an ocean coastline, woodlands, lakes, and ponds. In addition to nearly half of Mount Desert Island, the park designation also preserves a portion of the Schoodic Peninsula on the mainland, as well as the majority of Isle au Haut and Baker Island, all of Bar Island, three of the four Porcupine Islands (Sheep, Bald and Long), the Thrumcap (an islet), part of Bear Island, and Thompson Island in Mount Desert Narrows, as well as several other islands and islets.[6] Bar Island, which can be visited on foot over a sandbar around low tide,[7] and the Porcupine Islands are in Frenchman Bay by Bar Harbor.[6] About 57 mi (92 km) of carriage roads were designed and financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr. on Mount Desert Island,[8] 45 miles (72 km) of which continue to be maintained inside the park.[9]

Acadia National Park encompasses a total of 49,075 acres (19,860 ha; 76.680 sq mi; 198.60 km2) as of December 31, 2017.[1] At least 30,200 acres (12,200 ha; 47.2 sq mi; 122 km2) on Mount Desert Island are included in the park, along with 2,900 acres (1,200 ha; 4.5 sq mi; 12 km2) on Isle au Haut, about 200 acres (81 ha; 0.31 sq mi; 0.81 km2) on smaller islands, and 2,366 acres (957 ha; 3.697 sq mi; 9.57 km2) on the Schoodic Peninsula.[note 1][10][11] As of 2015, the permanent park boundary, as established by act of Congress in 1986, included 12,416 acres (5,025 ha; 19.400 sq mi; 50.25 km2) of privately owned land under conservation easements managed by the National Park Service, which plans to acquire the land at some point.[2]

Features

The mountains of Acadia National Park offer hikers expansive views of the ocean, island lakes, and pine forests. Twenty six significant mountains rise in the park, ranging from 284 ft (87 m) at Flying Mountain's summit to 1,530 ft (470 m) at Cadillac Mountain's summit.[12] Cadillac Mountain, named after the French explorer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, is on the eastern side of the island. Cadillac is the tallest mountain along the eastern coastline of the United States.[13] The summit of Cadillac is the first place in the United States where one may watch the sunrise from October 7 through March 6, due to its eastern location and height.[14]

The 27-mile (43 km) Park Loop Road leads to many scenic viewpoints along the coast, through forests and to the top of Cadillac Mountain.[13] The road traverses the eastern side of Mount Desert Island in a one-way, clockwise direction from Bar Harbor to Seal Harbor, passing features such as the Tarn (a pond), Champlain Mountain (location of a popular, exposed cliffside trail named Precipice),[15][16][17] the Beehive (another, smaller mountain), Sand Beach (a saltwater swimming area), Gorham Mountain, Thunder Hole (a crevasse into which waves crash loudly), Otter Cliff, Otter Cove, Seal Harbor, Jordan Pond, Pemetic Mountain, the Bubbles, Bubble Rock, Bubble Pond, Eagle Lake, and the side road to the summit of Cadillac Mountain. Some of the island's west side features include Echo Lake and beach (a designated freshwater swimming area), Acadia Mountain, Beech Mountain, Long Pond, and Seal Cove Pond. Bass Harbor Head Light is situated atop a cliff on the southernmost tip of the west side of the island.[6] Baker Island Light and Bear Island Light are the other two lighthouses managed by Acadia.[18]

Somes Sound is a five-mile (8 km) long fjard formed during a glacial period that nearly divides the island in half. The sound is 130 ft (40 m) deep at its deepest point, and is bordered by Norumbega Mountain to the east, and Acadia Mountain and Saint Sauveur Mountain to the west.[19][20] The towns of Southwest Harbor and Northeast Harbor face one another across the inlet to Somes Sound.[6]

History

Native people

Native Americans have inhabited the area called Acadia for at least 12,000 years, including the coastal areas of Maine, Canada, and adjacent islands. The Wabanaki Confederacy ("People of the Dawnland") consists of five related Algonquian nations—the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki and Penobscot. Some of the nations call Mount Desert Island Pemetic ("range of mountains"), which has remained at the center of the Wabanaki traditional ancestral homeland and territory of traditional stewardship responsibility to the present day.[21] The etymology of the park's name begins with the Mi'kmaq term akadie ("piece of land") which was rendered as l'Acadie by French explorers, and translated into English as Acadia.[22]

The Wabanaki traveled to the island in birch bark canoes to hunt, fish, gather berries, harvest clams and basket-making resources like sweetgrass, and to trade with other Wabanakis. They camped near places like Somes Sound.[21]

In the early 17th century, Asticou was the chieftain of the greater Mount Desert Island area, one district of an intertribal confederacy known as Mawooshen led by the grandchief Bashaba. Castine (Pentagoet in the native language) was the grandchief's favored rendezvous site for the Wabanaki tribes. The site is located just west of Mount Desert Island at the mouth of the Bagaduce River in eastern Penobscot Bay. From 1615, Castine developed into a major fur trading post where French, English, and Dutch traders all fought for control. Sealskins, moose hides, and furs were traded by the Wabanakis for European commodities. By the early 1620s, warfare and introduced diseases, including smallpox, cholera and influenza, had decimated the tribes from Mount Desert Island southward to Cape Cod, leaving about 10 percent of the original population.[23]

The border established between the United States and Canada after the American Revolution split the Wabanaki homelands. The confederacy was dissolved around 1870 due to pressure from the American and Canadian governments, though the tribal nations continued to interact in their traditional ways.[23] In the nineteenth century, Wabanakis sold handmade ash and birch bark baskets to travelers. The Wabanaki performed dances for summer tourists and residents at Sieur de Monts and the town of Bar Harbor. Wabanaki guides led canoe trips around Frenchman Bay and the Cranberry Islands.[21]

For two years, 1970–71, the nations operated a Wabanaki educational center called T.R.I.B.E. (Teaching and Research in Bicultural Education) on the west side of Eagle Lake. American Indian land claims in Maine were legally settled in 1980 and 1991. The annual Bar Harbor Native American Festival began in 1989, jointly sponsored by the tribes and the Abbe Museum.[23][24] The Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance was formed in 1993, assisting in the coordination of the annual festival with the museum.[23]

Currently, each tribe has a reservation and government headquarters located within their territories throughout Maine. Some Wabanakis live on Mount Desert Island, while others visit for board meetings at the Abbe Museum, to advise on and perform in exhibitions, for craft demonstrations, and to gather sweetgrass and sell handmade baskets at the annual festival.[21][23]

Exploration

The Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed along the coast of Mount Desert Island during an expedition for the French Crown in 1524. He was followed by Estêvão Gomes, a Portuguese explorer for the Spanish Crown in 1525. French explorer Jean Alfonse arrived in 1542. Alfonse entered Penobscot Bay and recorded details about the fur trade. Portuguese navigator Simon Ferdinando guided an English expedition in 1580.[23]

A few hundred people were living on Mount Desert Island when Samuel de Champlain arrived in 1604. Two Wabanakis led Champlain to Mount Desert Island, which he named Isle des Monts Deserts (Island of Barren Mountains) due to its barren peaks; he named Isle au Haut (High Island) due to its height.[23]

While he was sailing down the coast on 5 September 1604,[25] Champlain wrote:

That same day we also passed near an island about four or five leagues [12–15 mi; 19–24 km] in length, off which we were almost lost on a little rock, level with the surface of the water, which made a hole in our pinnace close to the keel. The distance from this island to the mainland on the north is not a hundred paces. It is very high and cleft in places, giving it the appearance from the sea of seven or eight mountains one alongside the other. The tops of them are bare of trees, because there is nothing there but rocks. The woods consist only of pines, firs, and birches.[26]

Settlement

.jpg.webp)

The first French missionary colony in America was established on Mount Desert Island in 1613. The colony was destroyed a short time later by an armed vessel from the Colony of Virginia as the first act of overt warfare in the long struggle leading to the French and Indian Wars. The island was granted to Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac by Louis XIV of France in 1688, but ceded to England in 1713. Massachusetts governor Sir Francis Bernard, 1st Baronet assumed control of the island in 1760. In 1790, Massachusetts granted the eastern half of the island to Cadillac's granddaughter, Mme. de Gregoire, while Bernard's son John retained ownership of the western half. The first record of summer visitors vacationing on the island was in 1855, and steamboat service from Boston was inaugurated in 1868. The Green Mountain Cog Railway was built from the shore of Eagle Lake to the summit of Cadillac Mountain in 1888. In 1901, the Maine Legislature granted Hancock County a charter to acquire and hold land on the island in the public interest. The first land was donated by Mrs. Eliza Homans of Boston in 1908, and 5,000 acres (2,000 ha; 7.8 sq mi; 20 km2) had been acquired by 1914.[27]

Rusticators

Artists and journalists had revealed and popularized the island in the mid-1800s. Painters came from the Hudson River School, including Thomas Cole and Frederic Church, inspiring patrons and friends to visit. The term rusticator was used to describe these early visitors who stayed in the homes of local fishermen and farmers for modest fees. The accommodations soon became insufficient for the increasing amount of summer visitors, and by 1880, thirty hotels were operating on the island. Tourism was becoming the major industry.[28]

Cottagers

For a select few Americans, the 1880s and the Gay Nineties meant affluence on a scale without precedent. Mount Desert Island, being remote from the cities of the east, became a summer retreat for families such as the Rockefellers, Morgans, Fords, Vanderbilts, Carnegies, and Astors. These families, with the help of developers such as Charles T. How,[29] constructed elegant estates, which they called cottages. Luxury, refinement, and large gatherings replaced the buckboard rides, picnics, and day-long hikes of the rusticators. For more than forty years, the wealthy dominated summer activity on Mount Desert Island, but the Great Depression and World War II brought an end to the extravagance.[28]

Park origins

The landscape architect Charles Eliot is credited with the idea for the park.[30] George B. Dorr, called the "Father of Acadia National Park", along with Eliot's father Charles W. Eliot (president of Harvard from 1869 to 1909), supported the idea both through donations of land and through advocacy at the state and federal levels. Dorr later served as the park's first superintendent. President Woodrow Wilson first established its federal status as Sieur de Monts National Monument on July 8, 1916, administered by the National Park Service.[2][31] It was the first national park created from private lands gifted to the public.[4]

We have entered on an important work; we have succeeded until the Nation itself has taken cognizance of it and joined with us for its advancement...No one who had not made the study of it which I have can realize how various and truly wonderful the opportunities are which the creation of this Park now opens, alike in wild life ways and splendid scenery. To lose by want of action now what will be so precious to the future, whether for the delight of men or as a means to study, would be no less than tragic.

— George B. Dorr, 1916, Acadia National Park: Its Origin and Background (1942), pp. 53 and 55[32]

Congress redesignated the national monument as Lafayette National Park on February 26, 1919,[2] the first American national park east of the Mississippi River[33] and the only one in the Northeastern United States. The park was named after the Marquis de Lafayette, an influential French participant in the American Revolution. Jordan Pond Road was started in 1922 and completed as a scenic motor highway in 1927.[34] The Cadillac Mountain Summit Road, begun in 1925, was completed in 1931.[34]

The name of the park was changed to Acadia National Park on January 19, 1929, in honor of the former French colony of Acadia which once included Maine.[2] In 1929 Schoodic Peninsula was donated to Acadia by John Godfrey Moore's second wife Louise and daughters Ruth and Faith. Keeping up with the taxes on the Schoodic land became a drain on the family finances and they thought this world be a fitting way to honor John Godfrey Moore. There was an unspoken stipulation in the discussions — the heirs were anglophiles that did not want to have their land as part of Lafayette National Park. Conservationist George Dorr, who is referred to as the "Father of Acadia National Park", suggested the name Acadia, and the deal went through after the name changed, ensuring the expansion.[35][36]

.jpg.webp)

From 1915 to 1940, the wealthy philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. financed, designed, and directed the construction of a network of carriage roads throughout the park.[9] He sponsored the landscape architect Beatrix Farrand, whose family owned a summer home in Bar Harbor named Reef Point Estate, to design the planting plans for the carriage roads (c. 1930).[37] The network originally encompassed about 57 miles (92 km)[8] of crushed stone carriage roads with 17 stone-faced, steel-reinforced concrete bridges (16 financed by Rockefeller), and two gate lodges—one at Jordan Pond and the other near Northeast Harbor.[38] About 45 miles (72 km) of carriage roads are maintained and accessible within park boundaries. Granite coping stones along carriage road edges act as guard rails; they are nicknamed "Rockefeller's Teeth."[9] The carriage roads are open from the end of the spring mud season, generally in late April, through the summer, autumn, and winter months, until the following spring thaw causes another closure in March to prevent damage to the gravel surface.[39][40]

Acadia National Park's first naturalist, Arthur Stupka, also had the distinction of being the first NPS naturalist to serve in any of the NPS's eastern United States districts. He joined the park staff in 1932, and in the capacity of park naturalist he wrote, edited and published a four-volume serial entitled Nature Notes from Acadia (1932–1935).[41]

Superintendents

| Superintendent | Start | End |

|---|---|---|

| George B. Dorr | February 26, 1919 | May 8, 1944 |

| Benjamin L. Hadley (acting) | July 8, 1944 | November 20, 1944 |

| Benjamin L. Hadley | November 20, 1944 | March 31, 1953 |

| Charles R. Scarborough (acting) | July 15, 1952 | November 4, 1953 |

| Frank R. Givens | December 4, 1953 | October 17, 1959 |

| Harold A. Hubler | October 18, 1959 | December 30, 1965 |

| Thomas B. Hyde | January 30, 1966 | May 4, 1968 |

| John M. Good | April 21, 1968 | August 8, 1971 |

| Keith E. Miller | August 22, 1971 | September 9, 1978 |

| Lowell White | October 9, 1978 | November 15, 1980 |

| Warner Forsell (acting) | November 16, 1980 | May 30, 1981 |

| Ronald N. Wrye | May 31, 1981 | July 19, 1986 |

| Robert Joseph Abrell (acting) | July 20, 1986 | January 31, 1987 |

| John A. Hauptman | January 2, 1987 | March 23, 1991 |

| Leonard V. Bobinchock (acting) | March 24, 1991 | April 5, 1991 |

| Robert W. Reynolds | May 5, 1991 | 1994 |

| Leonard V. Bobinchock (acting) | 1994 | 1994 |

| Paul Haertel | 1994 | 2002 |

| Leonard V. Bobinchock (acting) | 2002 | 2003 |

| Sheridan Steele | 2003 | 2015 |

| Kevin Schneider | 2015 |

Fire of 1947

Beginning on October 17, 1947, more than 10,000 acres (4,000 ha; 16 sq mi; 40 km2) of Acadia National Park burned in a fire that also destroyed an additional 7,000 acres (2,800 ha; 11 sq mi; 28 km2) of Mount Desert Island outside the park. The fire began along Crooked Road west of Hulls Cove (northwest of Bar Harbor). The forest fire was one of a series of fires that consumed much of Maine's forest in a dry year. The fire burned until November 14, and was fought by the Coast Guard, Army Air Corps, Navy, local residents, and National Park Service employees from around the country. Sixty-seven of the historic summer cottages along Millionaires’ Row, along with 170 other homes, and five hotels were destroyed. Restoration of the park was substantially supported by the Rockefeller family. Regrowth has occurred naturally with new deciduous forests consisting of birch and aspen enhancing the colors of autumn foliage, adding diversity to tree populations, and providing for the eventual regeneration of spruce and fir forests.[46]

Climate

The region is characterized by a large seasonal variation in temperature with warm to hot summers that are often humid, and cold to severely cold winters. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Mount Desert Island has a warm-summer humid continental climate (Dfb). The average annual temperature in the park is 47.3 °F (8.5 °C). July is the warmest month with an average of 69.7 °F (20.9 °C), while January is the coldest month with an average of 23.8 °F (−4.6 °C). The record high and low temperatures are 96 °F (36 °C) and -21 °F (−29 °C), respectively. The plant hardiness zone is 5b with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of −11.4 °F (−24.1 °C).[47]

Average annual precipitation in Bar Harbor is 55.54" (1411 mm). November is the wettest month with 5.89" (150 mm) of precipitation on average, while July is the driest month with 3.27" (83 mm). Precipitation days are spread evenly throughout the year with December averaging the most days with about 14, while August averages the least with about 9. The annual average days with precipitation is 139. Snow has been recorded from October to May, although the majority falls from December to March. The snowiest month is January with 18.3" (46 cm), and the annual average is 66.1" (167 cm).

| Climate data for Acadia National Park, Maine, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1982–2014 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 57 (14) |

61 (16) |

82 (28) |

85 (29) |

96 (36) |

95 (35) |

96 (36) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

83 (28) |

71 (22) |

63 (17) |

96 (36) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32.5 (0.3) |

34.9 (1.6) |

41.6 (5.3) |

53.2 (11.8) |

64.5 (18.1) |

73.9 (23.3) |

79.3 (26.3) |

78.3 (25.7) |

70.9 (21.6) |

58.5 (14.7) |

47.8 (8.8) |

37.8 (3.2) |

56.1 (13.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 23.8 (−4.6) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

33.3 (0.7) |

44.0 (6.7) |

54.7 (12.6) |

63.9 (17.7) |

69.7 (20.9) |

69.0 (20.6) |

61.9 (16.6) |

50.6 (10.3) |

40.3 (4.6) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

47.3 (8.5) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 15.1 (−9.4) |

17.5 (−8.1) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

34.8 (1.6) |

44.8 (7.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

60.2 (15.7) |

59.7 (15.4) |

52.8 (11.6) |

42.8 (6.0) |

32.7 (0.4) |

22.4 (−5.3) |

38.5 (3.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−18 (−28) |

−11 (−24) |

8 (−13) |

24 (−4) |

32 (0) |

36 (2) |

35 (2) |

31 (−1) |

16 (−9) |

3 (−16) |

−13 (−25) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.48 (114) |

3.84 (98) |

4.94 (125) |

5.15 (131) |

4.50 (114) |

4.28 (109) |

3.27 (83) |

3.45 (88) |

4.22 (107) |

5.86 (149) |

5.89 (150) |

5.66 (144) |

55.54 (1,411) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 17.0 (43) |

16.8 (43) |

15.5 (39) |

4.7 (12) |

trace | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

3.0 (7.6) |

14.6 (37) |

71.8 (182.11) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.1 | 9.8 | 12.2 | 11.6 | 13.5 | 12.1 | 10.8 | 9.3 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 13.7 | 138.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.3 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 23.0 |

| Source 1: NOAA (snow/snow days 1981–2010)[48][49] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS2[50] | |||||||||||||

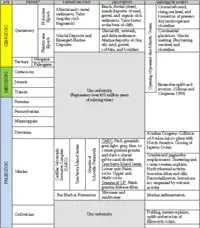

Geology

The Cadillac Mountain Intrusive Complex is part of the Coastal Maine Magmatic Province, consisting of over a hundred mafic and felsic plutons associated with the Acadian Orogeny. Mount Desert Island bedrock consists mainly of Cadillac Mountain granite. Perthite gives the granite its pinkish color. The Silurian age granite ranges from 424 to 419 million years ago (Mya). Diabase dikes trend north–south through the complex. Almost 300 million years of erosion followed before the deposition of glacial features during the Pleistocene. Glacial polish, glacial striations, and chatter marks are evident in granitic surfaces. Other glacier-shaped features include The Bubbles (two rôche moutonnées) and the U-shaped valleys of Sargent Mountain Pond, Jordan Pond, Seal Cove Pond, Long Pond, Echo Lake, and Eagle Lake. Somes Sound is a fjard and terminal moraines form the southern end of Long Pond, Echo Lake, and Jordan Pond. Bubble Rock is an example of a glacial erratic.[51]

Bedrock formation

More than 500 Mya, layers of mud, sand and volcanic ash were buried beneath the ocean where high pressure, heat and tectonic activity created a metamorphic rock formation called the Ellsworth Schist. White and gray quartz, feldspar, and green chlorite comprise the schist, which is the oldest rock in the Mount Desert Island region. Erosion and shifting of tectonic plates eventually brought the schist to the surface.[52]

About 450 Mya, an ancient continental fragment, or micro-terrane, called Avalonia collided with North America. The collision buried the schist along with accumulations of sand and silt, creating the Bar Harbor Formation which consists of brown and gray sandstone and siltstone layers. Material from volcanic flows and ash were also deposited on the formation, creating the volcanic rock found on the Cranberry Islands. Further volcanic activity introduced igneous rocks into the Bar Harbor Formation. As the igneous intrusions cooled, crystallized minerals formed including a gabbro composed of dark, iron-rich minerals.[52]

Mount Desert Island granite was created about 420 Mya, with one of the oldest granite bodies being Cadillac Mountain, the largest on the island. The granite body rose slowly through bedrock, fracturing it into large pieces, some of which melted under intense heat. As the granite cooled, the bedrock fragments were left surrounded by crystallized granite in a shatter zone that is visible on the eastern side of the mountain. A fine-grained, black igneous rock called diabase intruded into the granite during later volcanic activity. Diabase bodies, or dikes, are visible along the Cadillac Mountain road and on the Schoodic Peninsula.[52]

During the next several hundred million years, the rock layers that still covered the large granite bodies, along with softer rock surrounding the granite, were worn away by erosion.[52]

Glaciation

During the last two to three million years, a series of ice sheets flowed and receded across northern North America, eroding mountains and creating U-shaped valleys.[52] The glacier that covered Mount Desert Range, part of which is now called Mount Desert Island, was one-mile (1.6 km) thick and moved at the rate of a few yards (meters) per year. The mountain range was heavily eroded by the glacier which rounded off mountaintops, carved saddles, deepened valleys, and created the fjard known as Somes Sound, nearly dividing the current island in half.[20] Evidence of the last glacial period, the Wisconsin glaciation from about 75,000 to 11,000 years ago, is visible as long scratches, or striations, and crescent-shaped gouges created by material carried along at the base of the ice. As the climate warmed, the glaciers melted and receded, leaving boulders that had been carried 20 mi (32 km) or further south from their original locations. These boulders, or glacial erratics, lie in valleys and on mountaintops, including Bubble Rock on the South Bubble.[52]

The coastal areas of Maine sank slightly under the extreme weight of the ice sheets, allowing seawater to cover lowlands thus forming the present-day islands. Evidence of sea caves and past beaches can be found about 300 ft (91 m) above current sea level. As the ice receded and the land stabilized, lakes and ponds formed in valleys dammed by glacial debris. Rivers and streams flowed again through the watershed, continuing the gradual erosion of the drainage paths.[52]

Erosion and weathering

Acadia has a coastline composed of rocky headlands, and more heavily eroded stony or sandy beaches. Coastal areas directly facing the wind-driven waves of the Atlantic Ocean are solely composed of large boulders as all other material has been washed out to sea. Areas partially protected by rocky headlands contain the remains of more eroded rocks, consisting of pebbles, cobbles and smaller boulders. Sheltered coves, such as at Sand Beach, contain fine-grained particles that are primarily the remains of shells and other hard parts of marine life, including mussels and sea urchins.[52]

Granitic ridges are subjected to frost weathering. Joints, or fractures, are slowly enlarged as trapped water repeatedly freezes and melts, eventually splitting off a block. Bright pink scars with granitic rubble below are evidence of such weathering; one example can be seen above the Tarn, a pond just south of Bar Harbor.[52]

At least twelve sea caves are located in several coastal areas of the park. Sea caves are formed when waves cause erosion of coastal rock formations. If a sea cave is enlarged enough, it may break through a headland to form a sea arch.[53]

Mass wasting and slope failure

Frequent thawing in winter prevents large accumulations of snow, and keeps the ground well saturated. Ice storms are common in winter and early spring, while rain occurs throughout the year. Saturated soils, thawing, and heavy precipitation lead to rockfalls every spring along Mount Desert Island's loop road, as well as slumping along coastal bluffs.[53]

Mass wasting (slope movement) of marine clay, deposited when the sea level was much higher, occurs along Hunters Brook on Mount Desert Island. Slumping of the greenish-gray clay destabilized the bank, changing the course of the stream. The eastern end of Otter Cove's beach contains eroded gullies of marine clay. Mass wasting and slope failure may occur wherever marine clay is exposed.[53]

Seismic activity

Earthquakes with epicenters near the park have caused landslides, damaging roads and trails. Earthquakes in Maine occur at a low but steady rate, with magnitudes usually less than 4.8 on the Richter scale.[53]

Paleontology

The Presumpscot Formation has yielded a diverse collection of mostly marine fossils. The formation is composed of silt and clay deposited between 15 and 11,000 years ago when isostatic loading raised sea level as land was submerged to about 330–395 ft (101–120 m) above the current level. Post-glacial rebound lowered sea level, exposing the seabed to a depth of about 195 ft (59 m) below the current level. A global rise in sea-level flooded the shelf to the current level.[53]

Plant fossils include pollen, spores, logs, and other plant macrofossils. Invertebrate fossils include foraminifera (protists that form test shells), sponge spicules, bryozoans, bivalves, gastropods, Spirorbis, beetles, ants, barnacles, decapod crustaceans (crabs, shrimp, lobsters, etc.), ostracodes (seed shrimp), and ophiuroids (brittle stars). Vertebrate fossils include fish and a few rare large mammals, such as walruses, whales, and a mammoth. Walrus remains have been reported on Andrews Island, 19 mi (31 km) west of Isle au Haut; Addison Point, 23 mi (37 km) northeast of the Schoodic Peninsula; and Gardiner, 57 mi (92 km) west-northwest of Isle au Haut. The mammoth bones were found at Scarborough, 87 mi (140 km) southwest of Isle au Haut.[53]

Ecology

The ecological zones at Acadia National Park, from highest to lowest elevation, include: nearly barren mountain summits; northern boreal and eastern deciduous forests on the mountainsides; freshwater lakes and ponds, as well as wetlands like marshes and swamps in the valleys between mountains; and the Atlantic shoreline with rocky and sandy beaches, intertidal and subtidal zones.[54]

Tiny subalpine plants grow in the granite joints on mountaintops and on the downwind side of rocks. Stunted, gnarled trees also survive near the summits. Spruce-fir boreal forests cover much of the park. Stands of oak, maple, beech, and other hardwoods more typical of New England represent the eastern deciduous forest. Pitch pines and scrub oaks inhabit isolated forests at their northeastern range limit, while jack pines reach the southern limit of their range in Acadia.[54]

Fourteen great ponds and ten smaller ponds provide habitat for many fish and waterfowl species. More than 20% of the park is classified as wetland. Marshes and swamps form the transition between terrestrial and aquatic environments, maintaining biodiversity by providing a habitat for a wide range of species. Native wildlife frequent wetlands alongside species that are nesting, overwintering or migrating, such as birds along the Atlantic Flyway.[54] Wetlands are composed of 37.5% marine (sea water), 31.6% palustrine (stagnant water), 20% estuarine (coastal, brackish water), 10.7% lacustrine (freshwater lakes and ponds), and 0.2% riverine (flowing streams). Approximately 53.6 mi (86.3 km) of perennial streams and 47.3 mi (76.1 km) of intermittent streams flow through the park, while about 50 mi (80 km) of shoreline surround 110 lakes and ponds encompassing 1,056.56 acres (427.57 ha; 1.65088 sq mi; 4.2757 km2).[4]

Intertidal flora and fauna inhabit more than 60 mi (97 km) of rocky coastline.[4] The nutrient-rich marine waters cover the intertidal plants and animals twice a day. Pools of calm water form among the rocks around low tides, inhabited by starfish, dog whelks, blue mussels, sea cucumbers, and rockweed.[54]

Flora

Flora common to both deciduous and coniferous woodlands include lowbush blueberry, Canadian bunchberry, hobblebush, bluebead lily, Canada mayflower, wild sarsaparilla, shadbush, starflower, rosy twisted stalk, wintergreen, and white pine trees.[55]

Coniferous forest trees include the balsam fir, eastern hemlock, red pine, red spruce, and white spruce.[55] The park has a potential natural vegetation of northeastern spruce/fir within temperate coniferous forests, according to the original A. W. Kuchler types.[56] Spruce-fir forests cover more than sixty percent of the naturally vegetated habitats in the park.[4] Other coniferous forest plants include dewdrop, mountain holly, pinesap, one-flowered pyrola, shinleaf, trailing arbutus, northern woodsorrel, and drooping woodreed.[55]

An invasive insect known as the red pine scale was confirmed on dying red pines on the south side of Norumbega Mountain near Lower Hadlock Pond in 2014.[57]

Deciduous forest trees include the white ash, big-toothed and trembling aspen, American beech, paper and yellow birch, red oak, American mountain ash, as well as mountain, red, striped, and sugar maples. Other deciduous forest plants include large-leaved aster, chokecherry, red-berried elder, Christmas fern, threeleaf goldthread, early saxifrage, false Solomon's seal, small Solomon's seal, and twinflower.[55]

Trees commonly found in the mountains and dry, rocky places of the national park include gray birch, common juniper, jack pine, and pitch pine, while smaller trees, or shrub, species include green alder and pin cherry. Other common shrubs and flowering plants found in the mountains and rocky areas include alpine aster, bearberry, velvetleaf blueberry, bush-honeysuckle, black chokeberry, three-toothed cinquefoil, mountain cranberry, bracken fern, Rand's goldenrod, harebell, golden heather, mountain holly, black huckleberry, creeping juniper, sheep laurel, red raspberry, Virginia rose, mountain sandwort, bristly sarsaparilla, sweetfern, and wild raisin. Poverty oatgrass is the most common grass found in mountainous terrain.[55]

Bog plants include bog aster, bog rosemary, cottongrass, large cranberry, small cranberry, bog goldenrod, dwarf huckleberry, blue flag, Labrador-tea, bog laurel, leatherleaf, pitcher plant, rhodora, bristly rose, creeping snowberry, round-leaved sundew, spatulate-leaved sundew, and sweetgale, along with larch and black spruce trees.[55]

Meadow and roadside plants include speckled alder, flat-topped white aster, New York aster, blue-eyed-grass, azure bluet, spreading dogbane, fireweed, gray goldenrod, rough-stemmed goldenrod, wavy hair-grass, hardhack, whorled loosestrife, tall meadow-rue, meadowsweet, common milkweed, pearly everlasting, wild strawberry, and yellow rattle.[55]

Freshwater marsh and pond plants include common arrowhead, horned bladderwort, highbush blueberry, bluejoint, common cattail, water lobelia, pickerelweed, marsh St. John's wort, swamp candles, swamp rose, white turtlehead, fragrant water-lily, and yellow water-lily.[55]

The Mount Desert Island section of the park harbors more than half of the vascular plant species occurring in Maine.[4] Plant, algal, and fungal specimens collected during research activities at the park are deposited for future study at a herbarium jointly administered by the park and the College of the Atlantic.[58] A special garden called The Wild Gardens of Acadia was established in the Sieur de Monts area of the park in 1961 and has since grown to include more than 400 indigenous plant species found throughout all park areas.[59]

Fauna

The park's wide variety of natural habitats provides homes for many different animal species. The coastal location also encourages a large number of species; however, the small size and isolation of these habitats from mainland habitats limits the types of animals, especially their size. Smaller animals are better adapted to smaller habitats which makes them more common and easily observed than larger ones such as black bears and moose.[60]

The park is inhabited by 37 mammalian species:[61]

- carnivores – black bear, coyote, red fox (black, red, silver, and cross color variants), raccoon, North American river otter, fisher, American mink, short-tailed and long-tailed weasels

- ungulates – moose and white-tailed deer

- rodents – beaver, groundhog, porcupine, southern red-backed vole, five mouse species (white-footed, deer, southern bog lemming, woodland jumping and meadow jumping mouse), three squirrel species (northern flying, eastern gray, and red squirrel), and the eastern chipmunk

- shrews/moles – five shrew species (northern short-tailed, masked, smoky, pygmy, and water shrews), and the star-nosed mole

- bats – big brown, little brown, silver-haired, eastern red, hoary, and the northern long-eared bat (the fungal disease known as white-nose syndrome was confirmed in park bats in 2012)[62]

and a solitary native hare species, the snowshoe hare.

Seven reptilian species live in the park including five snakes (milk, smooth green, redbelly, eastern garter, and the ring-necked snake) and two turtles (the common snapping turtle and the eastern painted turtle).[61]

Eleven amphibian species inhabit the park including the American toad, five frog species (bullfrog, spring peeper, green, pickerel, and wood frog), four salamander species (spotted, dusky, northern two-lined, and four-toed salamander), and the eastern newt.[61]

The most abundant fish are the American eel, golden shiner, banded killifish, and pumpkinseed, while commonly found fish include alewife, white sucker, northern redbelly dace, chain pickerel (non-native), three-spined stickleback, nine-spined stickleback, rainbow smelt, and brook trout. Thirteen other fish species (ten non-native) are listed by the NPS as uncommon, while eight other species are listed with an unknown abundance.[61]

Many marine species may be observed in the surrounding waters, including seals and whales, from a sea kayak or other personal watercraft, or on ranger-narrated boat cruises. Special whale-watching excursions launch from Bar Harbor.[22]

A total of 215 bird species, including migratory birds, are present at some time during the year. An additional 116 species are possibly present but unconfirmed, making a total of 331 potential species. Thirty-three other bird species are considered historical and no longer present in the park. Large birds include golden and bald eagles, gyrfalcons, turkey vultures, ospreys, cormorants, and various herons, hawks, and owls. Waterfowl species include four geese (Canada, brant, snow, and greater white-fronted geese), along with various ducks including mallards, wood ducks, pintails, wigeons, blue-winged and green-winged teals, canvasbacks, buffleheads, eiders, goldeneyes, and harlequin ducks. Seabirds include terns and four gull species (herring, laughing, ring-billed, and great black-backed gulls), while shorebirds include avocets, sandpipers and plovers. Songbirds are represented by various species of blackbirds, chickadees, finches, jays, sparrows, swallows, thrushes, vireos, warblers, and wrens.[61]

One of the more unique songbirds is the red crossbill, a finch that uses its crossed mandibles to efficiently extract the seeds from conifer cones, especially those of spruces, hemlocks, and pines. The crossbills feed their young with the same seeds, rather than the insects which other species feed to their chicks. Any given subspecies of the crossbill (as many as ten are known in North America) will have the same bill size, utilize the same calls to communicate, and prefer certain cones, with smaller-billed birds preferring the smaller cones of hemlocks and larger-billed birds preferring the larger cones of white pines.[63]

In 1991, peregrine falcons had a successful nesting in Acadia for the first time since 1956. At least one pair and as many as four pairs have produced offspring over the years since 1991, totaling more than 160 chicks. Many of those chicks were banded to learn about migration, habitat use, and longevity. Banded falcons have been observed as far away as Vermont, Maryland, Washington, D.C., and New Brunswick. Beginning in early spring and continuing into mid-summer, certain trails may be closed to avoid disturbance to falcon nesting areas.[64] The Jordan Cliffs Trail, Valley Cove Trail, Precipice Trail, and a portion of the Orange and Black Path were closed from April 13 to July 13, 2018.[65][66] The same trails were closed from March 22 to August 3, 2017.[67][68]

Recreation

Motor vehicle touring along the 27-mile (43 km) Park Loop Road begins on April 15, if weather permits, and ends on December 1, unless significant snowfall closes it sooner. A two-mile (3.2 km) stretch of the Ocean Drive portion of the loop, from Schooner Head Road to Sand Beach and Otter Cliff, is plowed and open all year, as is Jordan Pond Road.[22][69]

The coastline can be explored on guided boat trips or by sea kayak. Canoeing and kayaking are popular activities on accessible lakes and ponds.[70] About 125 mi (201 km) of hiking trails traverse forests and mountains, while 45 mi (72 km) of carriage roads can be hiked or bicycled (motorized vehicles, including electric bikes, are prohibited).[71] Horseback riding is permitted on carriage roads and certain other park areas.[72] Climbing is popular at 60 ft (18 m) high Otter Cliff, and at Great Head, Precipice, and South Bubble.[73] Sand Beach offers seawater swimming and Echo Lake Beach offers freshwater swimming.[22] In summer, ocean water temperature ranges from 50–60 °F (10–16 °C) while lake and pond temperatures range from 55–70 °F (13–21 °C).[74]

Ranger-led programs from mid-May to mid-October introduce visitors to the park's diverse natural and cultural history. Park rangers offer short walks, longer hikes, boat cruises, evening amphitheater programs, and children's programs, as well as viewing of peregrine falcons and raptors.[22][75][76]

Winter activities include hiking on trails using snowshoes, or traction footwear, and trekking poles, cross-country skiing on carriage roads, snowmobiling on the paved loop road, and ice fishing on frozen ponds and lakes.[69]

Mount Desert Island has two NPS campgrounds, constructed mainly by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s along with various park trails.[77] Blackwoods Campground is located on the east side of the island, closer to the most popular sites, the carriage roads, and Bar Harbor. Seawall Campground is on the less crowded west side of the island.[22] Schoodic Woods on the Schoodic Peninsula is the newest NPS campground, opened in 2015.[78] Five lean-to shelters are available by advance reservation at Duck Harbor Campground on Isle au Haut.[22] Blackwoods is open throughout the year, though only primitive walk-in camping by permit is possible in winter (December–March), while the others are open from late spring (mid-to-late May) to early autumn (late September to mid-October).[79] Mount Desert Island also has eleven private campgrounds outside park boundaries, while two private campgrounds are on the Schoodic Peninsula, and one is on Isle au Haut.[80]

The park hosts the annual Acadia Night Sky Festival, attracting speakers, researchers, photographers, and artists to the area.[81][82]

Current issues and challenges

Congestion

Park attendance increased to 3.53 million in 2018, setting a new record for the second year in a row. The seasonal nature of the park means a concentration of visitors in the summer months that is beyond the capacity of park infrastructure. Congestion leads to lack of available parking and gridlock, requiring road closures. Traffic management places a toll on available rangers, competing with rescue operations that also see a sharp increase on peak attendance days.[83]

The Island Explorer bus system is offered in part to reduce congestion; it has served 7.7 million passengers since it began operations in 1999. A portion of park entrance fees partially funds the service.[84]

Environmental changes

Since the park's founding in 1916, climate change has lengthened the growing season by nearly two months. A longer growing season threatens native plants and invites invasive species that thrive in the longer, warmer summer season. An expanded warm season also lengthens the tourism season, placing further strain on park resources. Changes in rainfall patterns have also taxed park infrastructure, increasing the maintenance required to control erosion and protect the historic carriage roads.[85]

Deferred maintenance

Park officials estimated the cost of needed infrastructure maintenance to be $65.8 million in 2019, a $6 million increase from 2018.[86] The National Park Service has an estimated $11 billion in total deferred maintenance across all units, a number which continues to increase. The backlog compounds existing problems in environmental management and traffic congestion, as infrastructure to manage traffic flow cannot be built until existing infrastructure is properly maintained. Trail and wilderness restoration is also deferred due to insufficient funding. Additionally, the large number of park entrances creates issues with fee compliance, costing additional lost revenue.[87]

Visitor centers

Six visitor information centers are located in or near the park, including the main visitor center at Hulls Cove (northwest of Bar Harbor), a nature center at Sieur de Monts (south of Bar Harbor), an information center on Thompson Island (along the roadway to Mount Desert Island), another information center at Village Green in Bar Harbor, a historical museum in Islesford on Little Cranberry Island, and the Rockefeller Welcome Center on the Schoodic Peninsula. The Rockefeller Welcome Center is the only one open throughout the year, though it is closed on winter weekends; the others are all closed in winter.[79]

Schoodic Education and Research Center

After the naval base on the Schoodic Peninsula closed in 2002,[88] the National Park Service (NPS) acquired the land and established the Schoodic Education and Research Center (SERC). The SERC campus is managed by the nonprofit Schoodic Institute and the NPS in a public-private partnership as one of 19 NPS research learning centers in the country. The center is dedicated to supporting scientific research in the park, providing professional development for teachers, and educating students who will become the next generation of park stewards.[89][90]

Friends of Acadia

In 1986, a group of Acadia-area residents and park volunteers formed the membership-based nonprofit organization Friends of Acadia (FOA) to organize volunteer efforts and private philanthropy for the benefit of Acadia National Park.[91] The group's first major achievement was a $3.4 million endowment, raised between 1991 and 1996, to maintain the park's carriage road system in perpetuity, which leveraged federal funds to fully restore the road system. Subsequent projects and partnerships included Acadia Trails Forever, the first endowed trail system in an American national park with $13 million raised between 1999 and 2001, and the Island Explorer, a free, propane-powered bus system serving the park and local communities since 1999.[92]

The Acadia Youth Conservation Corps was established by FOA and endowed by an anonymous donor in 1999 to employ 16 high school students in maintenance of trails and carriage roads in the summer months.[93] FOA also partnered with park administration to establish the Acadia Youth Technology Team in 2011,[91] an initiative involving local teenaged interns and college-age team leaders supplied with professional-quality imaging tools to foster an appreciation of nature and environmental stewardship, especially among younger people.[94] The team has since been renamed the Acadia Digital Media Team.[95]

See also

Notes

- Total acreage figure as of 2017; Mount Desert Island, Schoodic Peninsula, and smaller islands acreage figures as of 2006; Isle au Haut acreage figure as of 2015; acreage figures may have increased in subsequent years as private land is acquired by the National Park Service.

References

- "National Reports - Park Acreage Reports (1997 – Last Calendar/Fiscal Year)". irma.nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

Select By Park; Calendar Year; select year; View PDF Report - see Gross Area Acres in the rightmost column of the report

- "Park Statistics". nps.gov. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Foundation Document: Acadia National Park (archive). pp. 28, 41 (of PDF file). nps.gov. National Park Service. September 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- Clement, Stephanie (May 4, 2022). "What Does Four Million Visits Mean To Acadia?". National Parks Traveler. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- "Acadia National Park Maps" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. March 2, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- "Tidepooling" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. December 4, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Schmitt, Catherine (2016). History Acadia National Park: The Stories Behind One of America's Great Treasures. Connecticut: Lyons Press. p. 130. ISBN 9781493018130. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018.

- "Acadia's Historic Carriage Roads" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. December 14, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- "Schoodic General Management Plan Amendment" (archive). page 3. nps.gov. National Park Service. April 2006. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- "National Park Service Completes Visitor Use Management Plan for the Isle au Haut District" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. February 26, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- "The 26 peaks of Acadia National Park". acadiaonmymind.com. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- "Places To Go: Scenic Areas" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. February 8, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- Trotter, Bill (October 22, 2011). "Where in Maine does the sun rise first?". Bangor Daily News. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- "Visitor rescued from fall on Precipice Trail" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. July 25, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Hiker suffers fall on Precipice Trail in Acadia National Park" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. December 27, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Man transported by LifeFlight from top of Champlain Mountain after fall in Acadia National Park" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. September 12, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Lighthouses". National Park Service. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- "Somes Sound, Mount Desert Island". Maine Geological Survey. November 1998. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- "The Story of Glaciers" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from "The Wabanaki: People of the Dawnland" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. December 14, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

This article incorporates public domain material from "The Wabanaki: People of the Dawnland" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. December 14, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2018. - "Frequently Asked Questions" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. October 26, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Prins, Harald E. L.; McBride, Bunny (December 2007). "Asticou's Island Domain: Wabanaki Peoples at Mount Desert Island 1500–2000, Acadia National Park, Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Volume 1" (archive). pp. 5-6, 19, 29. Northeast Region Ethnography Program of the National Park Service. Boston, Massachusetts. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- "Abbe Museum Native American Festival 2019" (archive). everfest.com. Everfest, Inc. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- Cammerer, Arno B. (1937). Acadia National Park. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office. p. 28. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018.

- Canadian-American Center. "Champlain and the Settlement of Acadia 1604-1607". University of Maine. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- Cammerer, Arno B. (1937). Acadia National Park. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018.

Search for each year: 1613, 1688, 1713, 1760, 1790, 1855, 1868, 1888, 1901, 1908 and 1914

-

This article incorporates public domain material from "History of Acadia" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. January 4, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

This article incorporates public domain material from "History of Acadia" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. January 4, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2018. - "Summer Residents Planning a Memorial to Charles T. How". The New York Times. September 3, 1911. p. 78.

- "History of Acadia". Acadia Net, Inc. November 1995. Archived from the original on April 1, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- "Sieur de Monts Spring" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. September 26, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- Dorr, George B. (1942) "Acadia National Park: Its Origin and Background" (archive). babel.hathitrust.org. HathiTrust Digital Library/Burr Printing Company, Maine. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- "Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. January 17, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- Cammerer, Arno B. (1937). Acadia National Park. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018.

- Holloway, Dillon (January 19, 2022). "Acadia renamed 93 years ago today". WVII / Fox Bangor. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- Dan_nehs (November 11, 2014). "John Godfrey Moore and How Acadia National Park Got its Name". New England Historical Society. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- Brown, Jane (March 1, 1995). Beatrix: the gardening life of Beatrix Jones Farrand, 1872–1959. Viking Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-670-83217-0.

- "The Carriage Roads of Acadia National Park" (archive). nps.gov. May 2007. National Park Service. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- "Carriage Roads Closed for Mud Season" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. March 2, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- Anastasia, Christie (April 27, 2018). "Carriage Roads open for Spring 2018". nps.gov; National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- "DigitalCommons@UMaine – Advanced Search title:( Nature Notes from Acadia )". The University of Maine. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- "National Park Service: Historic Listings of NPS Officials (Superintendents of National Park System Areas)". npshistory.com. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "List of Park Superintendents" (PDF). Friends of Acadia Journal. 16 (3): 29. 2011.

- "Wildland Fire: Fire Management Program" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. May 7, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018. "...prescribed fire for management of park vistas and cultural landscapes"

- "National Park Service set to conduct prescribed fire burn on Friday May 18, 2018" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. May 17, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018. "...to perpetuate native plant species and open space landscapes...[and] reduce natural hazard fuels, which will help minimize fire risk to park and adjacent lands."

- "Fire of 1947". National Park Service. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

Bar Harbor's Zip Code is 04609

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Acadia NP, ME (1991–2020)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Acadia National Park, ME (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- "xmACIS2". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- Graham, J. (August 2010). "Acadia National Park: geologic resources inventory report. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2010/232" (PDF). Fort Collins, Colorado: National Park Service. pp. 1–63. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018.

PDF file link found on: irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2124944

-

This article incorporates public domain material from Written in Acadia's Rocks. National Park Service. March 16, 2015. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

This article incorporates public domain material from Written in Acadia's Rocks. National Park Service. March 16, 2015. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018. -

This article incorporates public domain material from "NPS Geodiversity Atlas—Acadia National Park, Maine" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. December 6, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

This article incorporates public domain material from "NPS Geodiversity Atlas—Acadia National Park, Maine" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. December 6, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2018. -

This article incorporates public domain material from "Natural Features & Ecosystems" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. September 28, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Natural Features & Ecosystems" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. September 28, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2018. - "Common Native Plants" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. July 15, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- "U.S. Potential Natural Vegetation, Original Kuchler Types, v2.0 (Spatially Adjusted to Correct Geometric Distortions)". databasin.org. Conservation Biology Institute. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- "Invasive Insect Contributing to Red Pine Die-off on Mount Desert Island" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. February 26, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "The College of the Atlantic/Acadia National Park Herbarium" (archive). coa.edu. College of the Atlantic. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- Friends of Acadia. "The Wild Gardens of Acadia Visitor Information: History of the Gardens". friendsofacadia.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- "Acadia National Park Animals" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. November 30, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- "Species List | Acadia National Park". nps.gov. National Park Service. June 25, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2018. "Species listed here are based on the Checklist results, not the Full list results. For mammals, the full list contains eleven unconfirmed species such as the gray wolf and Canada lynx, and seven historical species such as the striped skunk and bobcat. The abundance of each species (abundant, common, uncommon, rare, unknown) is provided in the full list."

- "White-nose syndrome confirmed in Acadia" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. February 26, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Species Spotlight - Red Crossbill" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. January 26, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- "Peregrine Falcons in Acadia" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. March 16, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- "Peregrine falcons return to nest, trails closed to public entry" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. April 15, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Peregrine Falcon Nesting Areas Reopen" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. July 13, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Peregrine falcons nest in Acadia National Park" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. March 23, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Peregrine falcon nesting areas reopen in Acadia National Park" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. August 1, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Winter Activities" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. February 1, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- "Boating" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. January 31, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- "Bicycling" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. August 2, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- "Horseback Riding" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. May 11, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- "Climbing" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. October 26, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- "Weather" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. October 26, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Ranger Program Descriptions" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. August 28, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Guided Tours" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. August 28, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Civilian Conservation Corps" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. July 12, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- "Acadia Announces the Grand Opening of Schoodic Woods Campground" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. September 1, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- "Operating Hours & Seasons" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. October 30, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- "Private Campgrounds" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. February 13, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- "Maine's night sky beckons stargazers to Acadia National Park". apnews.com. The Associated Press. September 3, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Firpo-Capiello, Robert (February 7, 2018). "Acadia's Dark Sky Festival Is Calling All…". budgettravel.com. Budget Travel. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "Record-Setting Visitation To Acadia National Park Not Without Problems". www.nationalparkstraveler.org. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "Island Explorer adds new propane-powered buses to fleet". Ellsworth American. July 6, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "How scientists say climate change will impact Acadia National Park". WCSH. August 21, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "Acadia has a $65M list of maintenance projects, but not enough funds to pay for them". Bangor Daily News. August 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- Tourist Impact in Acadia National Park (PDF) (Report). Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

- "The Navy at Schoodic Point" (archive). schoodicinstitute.org. Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- "Schoodic Institute - Mission & History" (archive). schoodicinstitute.org. Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- "Schoodic Education and Research Center" (archive). nps.gov. National Park Service. January 4, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- "Friends of Acadia History". friendsofacadia.org. Friends of Acadia. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- "Friends of Acadia Accomplishments". friendsofacadia.org. Friends of Acadia. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- "Acadia Youth Conservation Corps". friendsofacadia.org. Friends of Acadia. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- "Acadia Youth Technology Team". friendsofacadia.org. Friends of Acadia. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- "Employment Opportunities". friendsofacadia.org. Friends of Acadia. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

External links

- Official website

of the National Park Service (NPS)

of the National Park Service (NPS) - Weather forecast of the National Weather Service

- Blackwoods, Seawall and Schoodic Woods campgrounds at Recreation.gov

- Air quality images (NPS)

- Timelapse video of park's growth (NPS)

- Acadia National Park: Its Origin and Background by George B. Dorr (1942)

- Proclamation by President Woodrow Wilson (archive)

- Lafayette National Park Act (archive)

- Historic American Engineering Record documentation, all filed under Hancock County, ME:

- HAER No. ME-11, "Acadia National Park Motor Roads", 27 photos, 8 color transparencies, 49 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- HAER No. ME-12, "Acadia National Park Roads and Bridges, Mount Desert Island, Bar Harbor", 19 measured drawings

- HAER No. ME-14, "Sieur de Monts Spring Bridge, Spanning Park Loop Road at Route 3 near Sieur de Monts Spring, Bar Harbor", 1 photo, 6 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-15, "Blackwoods Bridge, Spanning Park Loop Road at Route 3 near Blackwoods, Otter Creek", 2 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-16, "Fish House Bridge, Spanning Fish House Access Road at Park Loop Road, Otter Creek", 3 photos, 5 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-17, "Route 233 Bridge, Spanning Route 233 on Paradise Hill Road, Bar Harbor", 2 photos, 6 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-18, "New Eagle Lake Road Bridge, Spanning New Eagle Lake Road on Paradise Hill Road, Bar Harbor", 3 photos, 6 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-19, "Otter Creek Cove Bridge and Causeway, Spanning Otter Creek Cove on Park Loop Road, Seal Harbor", 6 photos, 3 color transparencies, 1 measured drawing, 17 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-20, "Kebo Brook Bridge, Spanning Kebo Brook on Park Loop Road, Bar Harbor", 4 data pages

- HAER No. ME-21, "Little Hunters Beach Brook Bridge, Spanning Little Hunters Beach Brook on Park Loop Road, Seal Harbor", 1 photo, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-22, "Hunters Beach Brook Bridge, Spanning Hunters Beach Brook on Park Loop Road, Seal Harbor", 2 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-23, "Frazer Creek Bridge, Spanning Frazer Creek on Schoodic Peninsula Road, Winter Harbor", 1 photo, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-30, "Duck Brook Bridge, Spanning Duck Brook on Paradise Hill Road, Bar Harbor", 4 photos, 1 color transparency, 1 measured drawing, 7 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. ME-47, "Wildwood Farm Bridge, Spanning Abandoned Road on Park Loop Road, Seal Harbor", 2 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page